In 1862 Giles Smith began life with a handicap that few people can imagine today: He was born into slavery on a plantation in Alabama.

On September 14, 1937, at age seventy-nine, Smith was living on Blanchard Street in Fort Worth when he recalled his life to a transcriptionist of the Federal Writers’ Project.

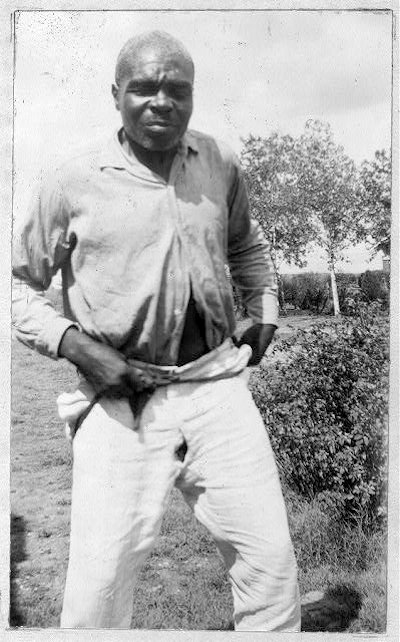

Photo of Giles Smith from the Library of Congress.

Photo of Giles Smith from the Library of Congress.

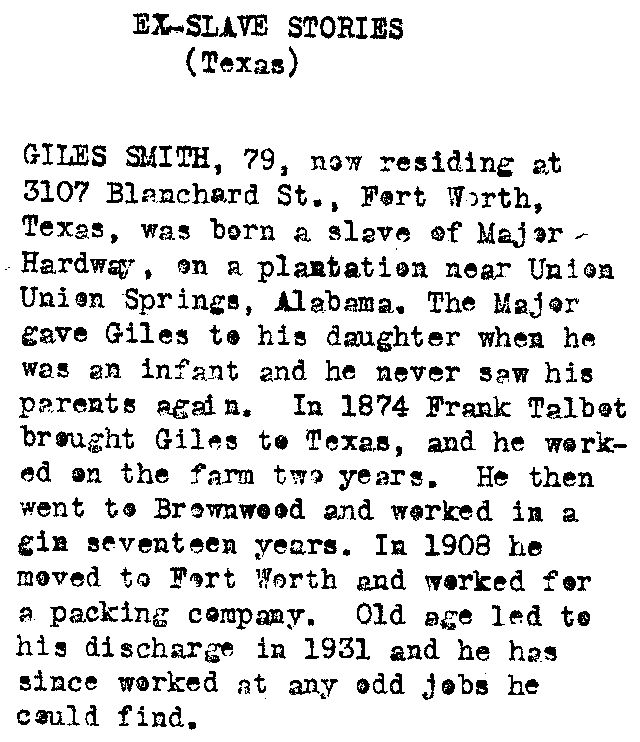

This is the transcriptionist’s abstract of the interview with Giles Smith. (Federal Writers’ Project accounts inevitably contain errors and inconsistencies. According to Smith, he came to Fort Worth about 1922, not 1908.)

This is the transcriptionist’s abstract of the interview with Giles Smith. (Federal Writers’ Project accounts inevitably contain errors and inconsistencies. According to Smith, he came to Fort Worth about 1922, not 1908.)

Here is Giles Smith’s story in his own words:

My name am Giles Smith, ’cause my pappy was born on the Smith plantation and I took his name. I’s born at Union Springs in [Bullock County] Alabama and Major Hardway owned me and ’bout a hundred other slaves. But he gave me to Mary, his daughter, when I’s only a few months old and had to be fed on a bottle, ’cause she am jus’ married to Massa Miles. She told me how she carried me home in her arms. She say I was so li’l she have a hard time to make me eat out the bottle, and I put up a good fight so she nearly took me back.

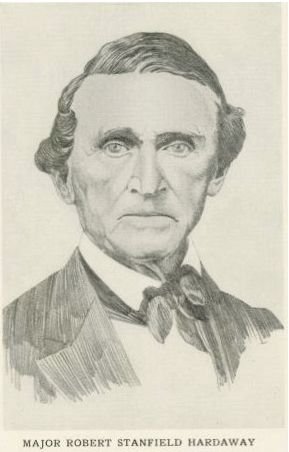

[“Major Hardway” may have been Major Robert Stanfield Hardaway (1797-1875). He owned plantations with slaves in Macon and Russell counties (adjacent to Bullock County) in Alabama and in Muscogee County, just across the state line in Georgia. (Photo from Chattahoochee Valley Libraries.)]

[“Major Hardway” may have been Major Robert Stanfield Hardaway (1797-1875). He owned plantations with slaves in Macon and Russell counties (adjacent to Bullock County) in Alabama and in Muscogee County, just across the state line in Georgia. (Photo from Chattahoochee Valley Libraries.)]

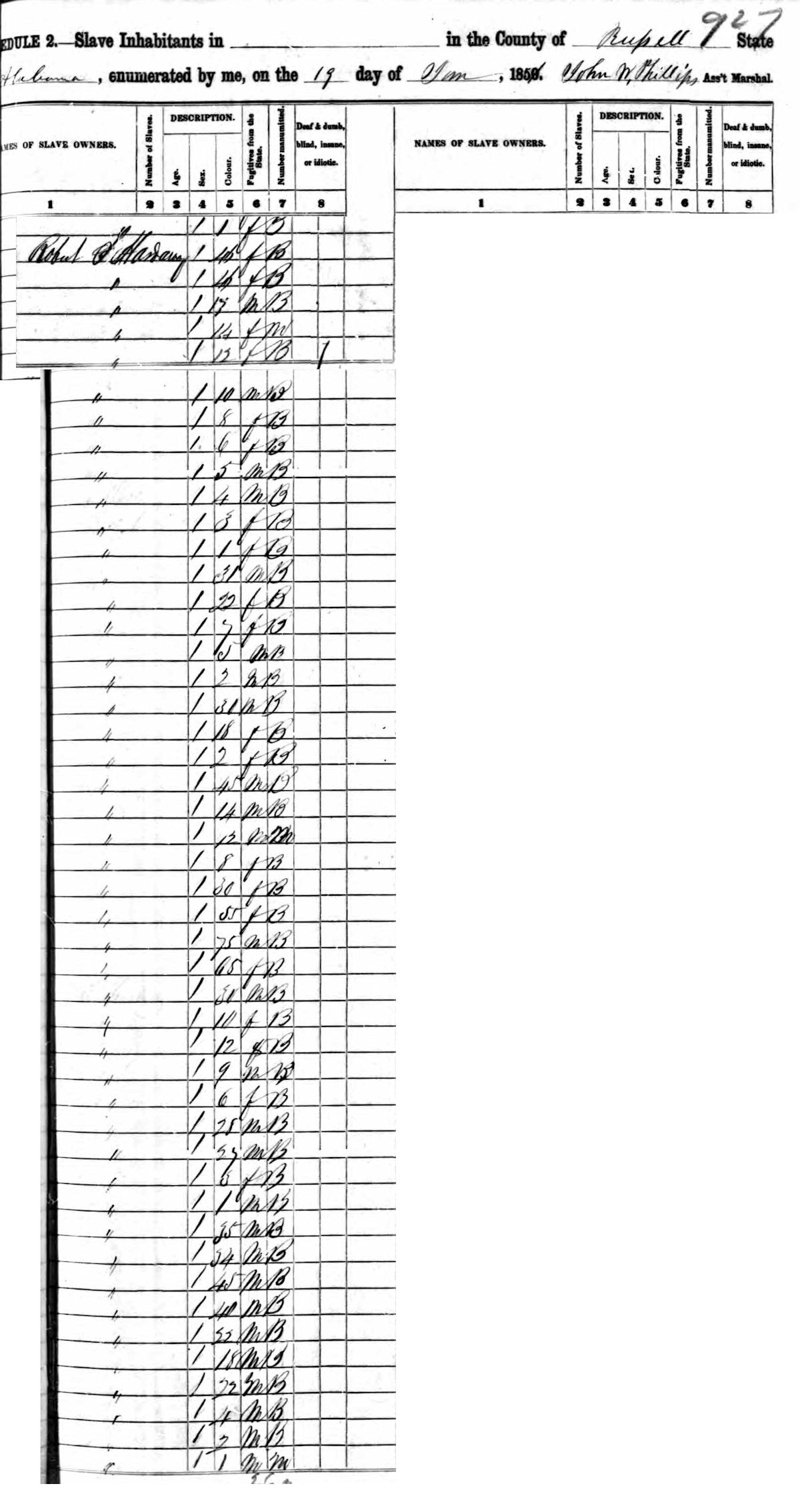

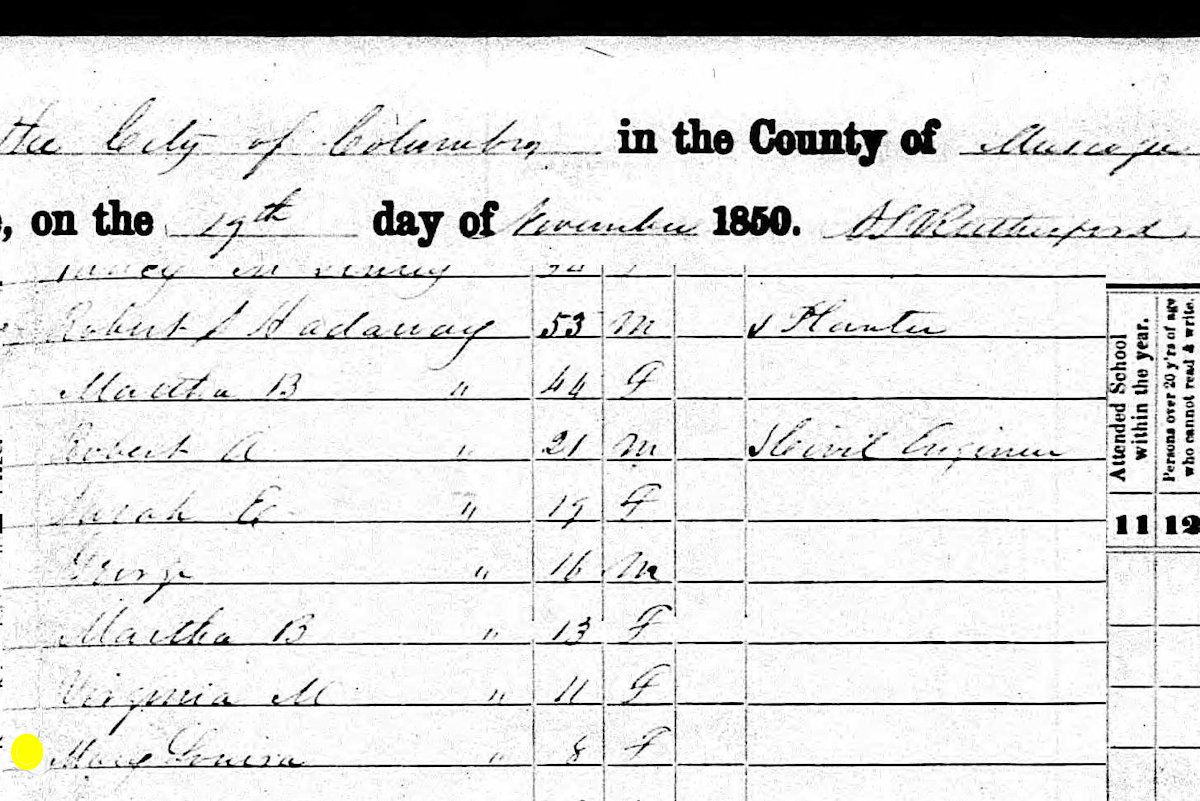

[The 1850 slave schedule of Russell County lists the slaves of Major Hardaway.]

[The 1850 slave schedule of Russell County lists the slaves of Major Hardaway.]

[The 1850 census of Muscogee County lists planter Robert Hardaway with a daughter named “Mary Louisa” who would be about twenty when Giles Smith was born in 1862.

[The 1850 census of Muscogee County lists planter Robert Hardaway with a daughter named “Mary Louisa” who would be about twenty when Giles Smith was born in 1862.

Giles Smith continues his story:]

I don’t ’member the start of the war, but de endin’ I does. Massa Miles called all us together and told us we’s free and it give us all de jitters. He treated all us fine and nobody wanted to go. He and Missy am de best folks de Lawd could make. I stayed till I was sixteen years old.

It am years after freedom Missy Mary say to me what Massa allus say, “If the nigger won’t follow orders by kind treatin’, sich nigger am wrong in the head and not worth keepin’.” He didn’t have to rush us. We’d just dig in and do the work. One time Massa clearin’ some land and it am gittin’ late for breakin’ the ground. Us allus have Saturday afternoon and Sunday off. Old Jerry says to us, “Tell yous what us do—go to the clearin’ this afternoon and Sunday and finish for the Massa. That sho’ make him glad.”

Saturday noon came and nobody tells the Massa but [we] go to that clearin’ and sing while us work, cuttin’ bresh and grubbin’ stumps and burnin’ bresh. Us sing

“Hi, ho, ug, hi, ho, ug

De sharp bit, de strong arm,

Hi, ho, ug, hi, ho, ug,

Dis tree am done ’fore us warm.”

De Massa com out and his mouth am slippin’ all over he face and he say, “What this all mean? Why you workin’ Saturday afternoon?”

Old Jerry am a funny cuss and he say, “Massa, o Massa, please don’t whip us for cuttin’ down yous trees.”

“I’s gwine whip you with the chicken stew,” Massa say, “and for Sunday dinner dere am chicken stew with noodles and peach cobbler.”

So I stays with Massa and after I’s fifteen he pays me $2.00 the month, and course I gits my eats and my clothes, too. When I gits the first two I don’t know what to do, ’cause it the first money I ever had. Missy make the propulation [sic] to keep the money and buy for me and teach me ’bout it. There ain’t much to buy, ’cause we make nearly everything right there. Even the tobaccy am made. They put honey ’twixt the leaves and put a pile of it ’twixt two boards with weights. It am left for a month and that am a man’s tobaccy. A weaklin’ better stay off that kind tobaccy.

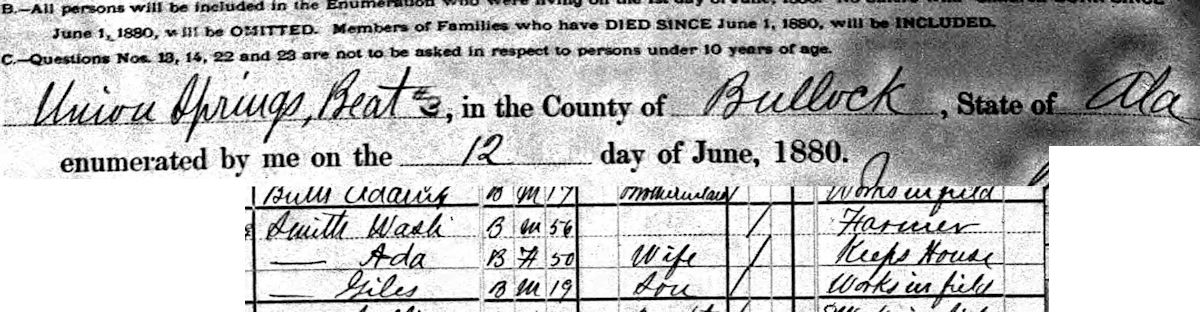

[The 1880 census of Union Springs, Alabama lists an African-American field worker named “Giles Smith,” born about 1861.]

[The 1880 census of Union Springs, Alabama lists an African-American field worker named “Giles Smith,” born about 1861.]

First I works in the field and then am Massa’s coachman. But when I’s ’bout sixteen I gits a idea to go off somewhere for myself. I hears ’bout Mr. Frank Talbot, who am takin’ some niggers to Texas and I goes with him to the Brazos River bottom and work there two years. I’s lonesome for Massa and Missy and if I’d been close enough I’d sho’ gone back to the old plantation. So after two years I quits and goes to work for Mr. Winfield Scott down in Brownwood, in the gin, for seventeen years.

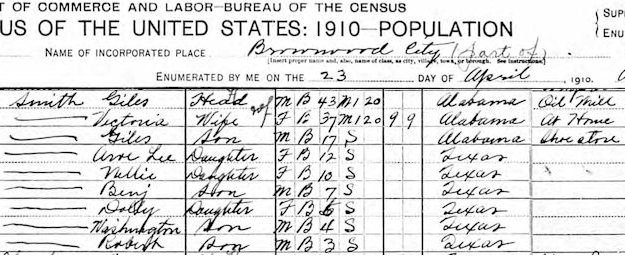

[Winfield Scott, Fort Worth’s biggest taxpayer and owner of Thistle Hill on Quality Hill, owned the Cottonseed Oil Mill in Brownwood. The 1910 Brownwood census shows Giles Smith working at the “oil mill.”]

[Winfield Scott, Fort Worth’s biggest taxpayer and owner of Thistle Hill on Quality Hill, owned the Cottonseed Oil Mill in Brownwood. The 1910 Brownwood census shows Giles Smith working at the “oil mill.”]

Well, shortly after I gits to Brownwood I meets a yaller gal [“high yellow,” of mixed race, e.g., Emily D. West (the Yellow Rose of Texas)] and after dat I don’t care to go back to Alabama so hard. I’s married to Dee Smith on December the eighteenth, in 1880, and us live together many years. She died six years ago. Us have six chillen but I don’t know where one of them are now. They all forgit their father in his old age! They not so young, either.

My woman could write a little so she write Missy for me, and she write back and wish us luck and if we ever wants to come back to the old home we is welcome. Us write back and forth with her. Finally, us gits the letter what say she sick, and then awful low. That ’bout twenty-five years after I marries. That am too much for me, and I catches the next train back to Alabama but I gits there too late. She am dead, and I never has forgive myself, ’cause I don’t go back befo’ she die, like she ask us to, lots of times.

I comes here [Fort Worth] fifteen years ago and here I be. The last six year I can’t work in the packin’ plants no more. I’s too old. Anything I can find to do I does, but it ain’t much no more.

The worst grief I’s had, am to think I didn’t go see Missy ’fore she die. I’s never forgive myself for that. [Mary Louisa Hardaway died in 1910 in Alabama.]

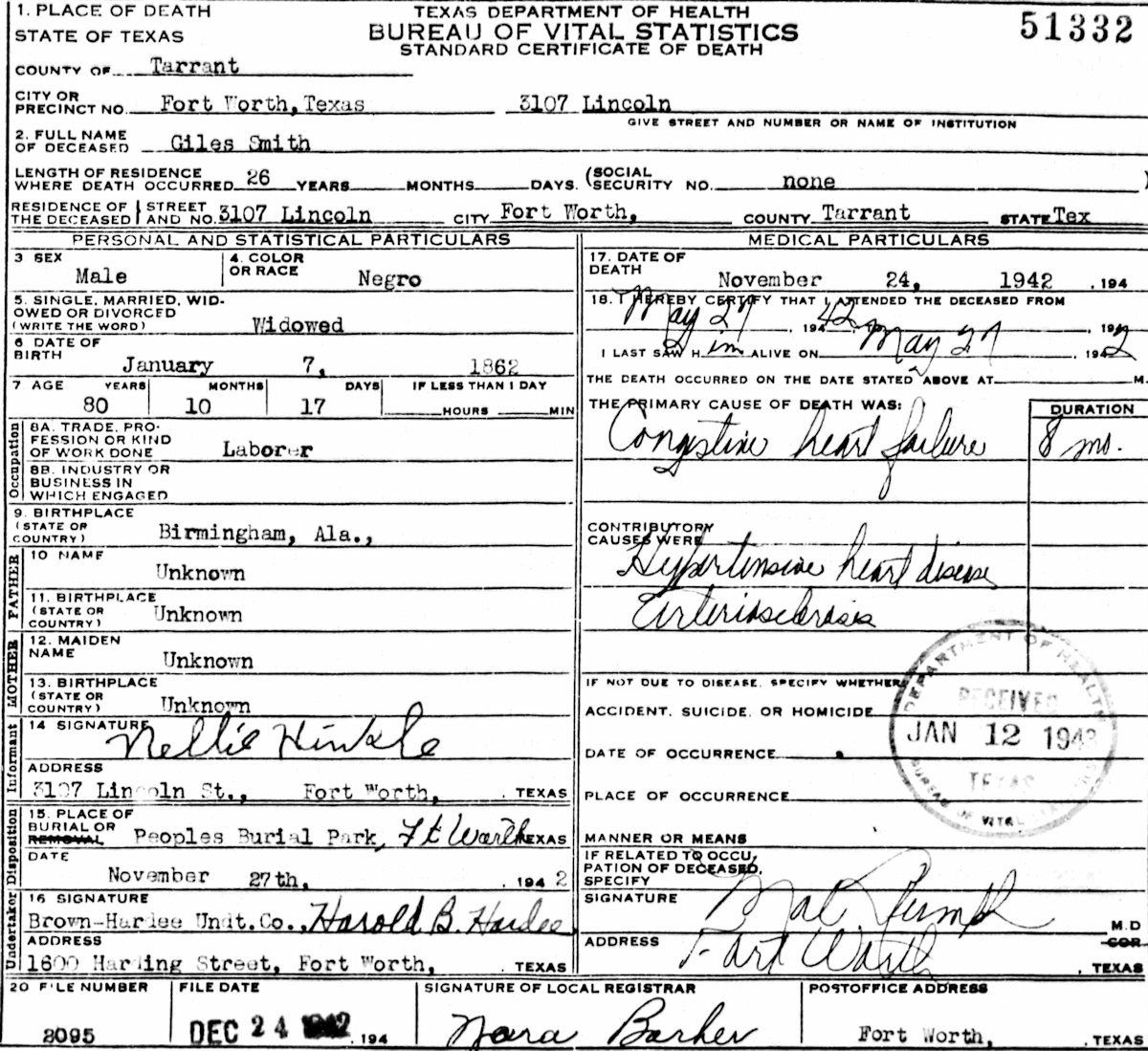

Giles Smith was living on Lincoln Avenue on the North Side when he died on November 24, 1942. He is buried in New Trinity Cemetery.

Giles Smith was living on Lincoln Avenue on the North Side when he died on November 24, 1942. He is buried in New Trinity Cemetery.

Some caveats: (1) Many of the ex-slaves interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s had been children during slavery and may have received less-harsh treatment (and thus have retained less-harsh memories) than did adult slaves who were no longer alive to be interviewed in the late 1930s. (2) Lacking mechanical recording equipment, the interviewers sometimes took notes during interviews and transcribed the notes afterward, relying on memory, not “taking dictation” as the ex-slaves spoke. (3) The ex-slaves may have told interviewers, who were usually white, what the ex-slaves thought the interviewers wanted to hear (e.g., that white overseers had been kind). (4) The interviews were conducted during the Great Depression, when ex-slaves may have been afraid to endanger their often-precarious financial situation by offending the white establishment of their community.

More memories of Fort Worth residents who were born into slavery:

Verbatim: “I’se Bo’n in Slavetime” (Part 1)

Verbatim: Philles and William (“Jesus’ Lamb” and “Dat Old Cuss”)

Verbatim: “I Hears Marster Say Dem Was de Quantrell Mens”

Verbatim: “Us Am de Cons’lation to Each Other”

More “Verbatim” memories

dis it x c lant dar mike.yo mite mak a bo na fide massar scribler.yaz ser.da massas I wok fo tru da yers sho not giv me no nice vittles like chikin an noddles,but thez no beat me none neather,but I made a bit mo than two bucks a day..but this is the best one yet.thake off thanks giving,if you work massa gonna beat you wit some chickin and taters.