In the pantheon of Fort Worth architects they are not well known, even though for a while they partnered with one of Fort Worth’s premier architects and designed for one of Fort Worth’s most ambitious developers.

And today not many of their buildings survive, in part because several of them burned in some of the biggest fires in Fort Worth history.

Arthur Albert Messer was born in England in 1864 and trained there as an architect. He came to Texas in 1888 and became the partner of Fort Worth architect A. J. Armstrong. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

Arthur Albert Messer was born in England in 1864 and trained there as an architect. He came to Texas in 1888 and became the partner of Fort Worth architect A. J. Armstrong. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

Among Armstrong and Messer’s early projects were train depots in other towns and commercial buildings for Hyde Jennings and A. T. Byers.

Among Armstrong and Messer’s early projects were train depots in other towns and commercial buildings for Hyde Jennings and A. T. Byers.

Armstrong and Messer also designed the 1890 Hurley Building. In 1898 the Hurley Building was destroyed in what the Houston Daily Post called “the most disastrous fire in the history of Fort Worth.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

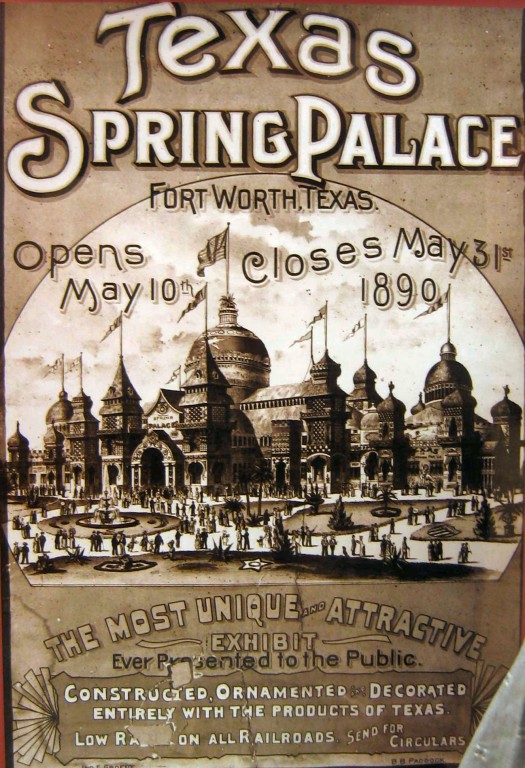

But Arthur Messer’s masterpiece was the sprawling, exotic Texas Spring Palace (1889). The Spring Palace was sprawling and exotic, but it also was flammable. On the second-to-last night of its second season it burned to the ground in what B. B. Paddock would later call “a blaze of glory.”

But Arthur Messer’s masterpiece was the sprawling, exotic Texas Spring Palace (1889). The Spring Palace was sprawling and exotic, but it also was flammable. On the second-to-last night of its second season it burned to the ground in what B. B. Paddock would later call “a blaze of glory.”

In 1891 Arthur’s older brother Howard joined him in Fort Worth. Howard, born in 1861, also had trained as an architect in England. (Photo from the Mersea Museum.)

In 1891 Arthur’s older brother Howard joined him in Fort Worth. Howard, born in 1861, also had trained as an architect in England. (Photo from the Mersea Museum.)

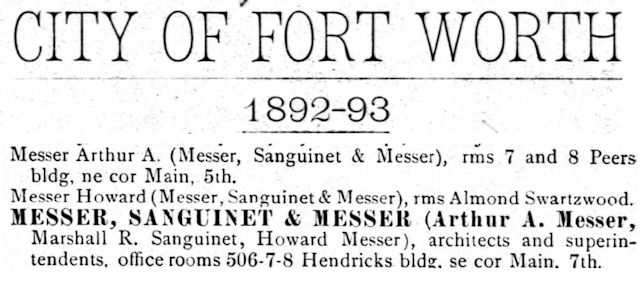

Soon after Howard arrived, the Messer brothers partnered with architect Marshall Sanguinet. Although Sanguinet was already established here, Arthur Messer was the top-billed partner of the new firm.

Soon after Howard arrived, the Messer brothers partnered with architect Marshall Sanguinet. Although Sanguinet was already established here, Arthur Messer was the top-billed partner of the new firm.

Sanguinet in 1890 had become the architect for British-born Humphrey Barker Chamberlin as Chamberlin developed his Arlington Heights addition west of town. Beginning in 1891 the firm of Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer designed most of the first houses in Arlington Heights.

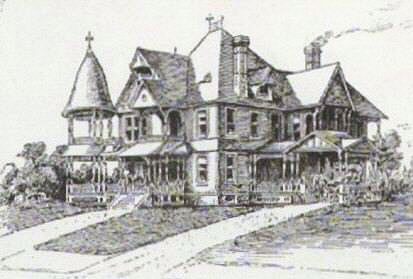

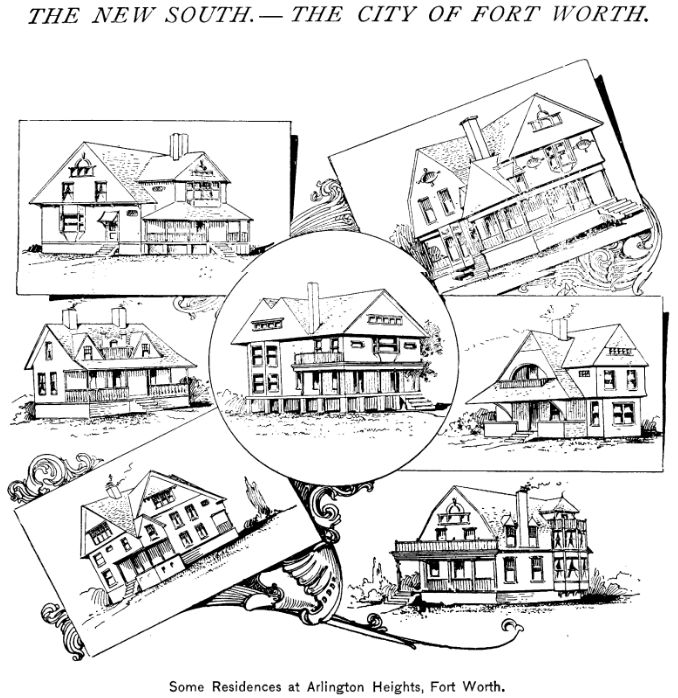

In 1891 New England Magazine published a feature entitled “The New South—The City of Fort Worth.” The magazine devoted much of the feature to Arlington Heights, picturing the 1890 Arlington Heights model home, which also was the residence of Chamberlin executive Henry W. Tallant.

In 1891 New England Magazine published a feature entitled “The New South—The City of Fort Worth.” The magazine devoted much of the feature to Arlington Heights, picturing the 1890 Arlington Heights model home, which also was the residence of Chamberlin executive Henry W. Tallant.

The feature also pictured other early houses in Arlington Heights. Most, if not all, of the houses were designed by Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer.

The feature also pictured other early houses in Arlington Heights. Most, if not all, of the houses were designed by Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer.

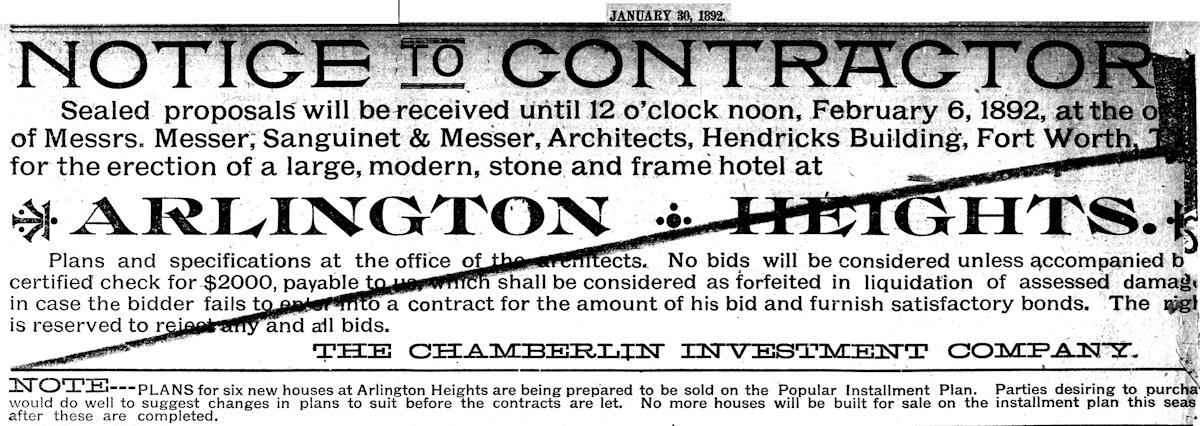

Chamberlin wanted his upscale addition to have an upscale hotel. In 1892 Sanguinet and the Messer brothers designed Ye Arlington Inn. In 1894 yet another Messer project went up in flames as Ye Arlington Inn burned to the ground.

Chamberlin wanted his upscale addition to have an upscale hotel. In 1892 Sanguinet and the Messer brothers designed Ye Arlington Inn. In 1894 yet another Messer project went up in flames as Ye Arlington Inn burned to the ground.

Meanwhile, Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer put their money where their T-square was: In 1890 Sanguinet had become one of the first residents of Arlington Heights, building a house of his own design. It burned, and he rebuilt it in 1894.

Meanwhile, Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer put their money where their T-square was: In 1890 Sanguinet had become one of the first residents of Arlington Heights, building a house of his own design. It burned, and he rebuilt it in 1894.

Likewise, the Messer brothers were among the first residents of Arlington Heights, designing their own homes. In 1893 Arthur Messer built this house at 5220 Locke Avenue.

Likewise, the Messer brothers were among the first residents of Arlington Heights, designing their own homes. In 1893 Arthur Messer built this house at 5220 Locke Avenue.

Howard Messer lived on El Campo Avenue.

Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer also designed Fairview (1893), the Arlington Heights home of masonry contractor and future mayor William Bryce. Fairview is located on the street named for Bryce.

Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer also designed Fairview (1893), the Arlington Heights home of masonry contractor and future mayor William Bryce. Fairview is located on the street named for Bryce.

Across the street from Fairview is the home (1893) of Lillie Burgess Smith.

Across the street from Fairview is the home (1893) of Lillie Burgess Smith.

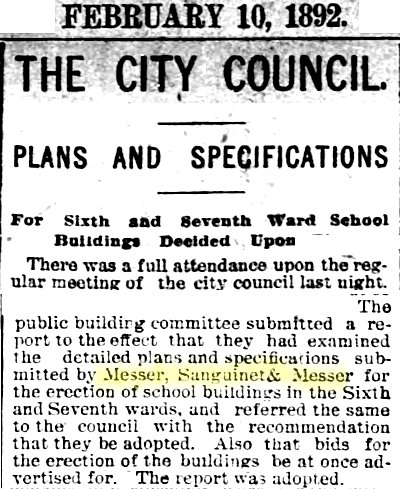

But for Sanguinet and the Messer brothers, there was life—and a living—outside Arlington Heights. In 1892 they designed two ward schools. The Sixth Ward school building survives on Lipscomb Street.

But for Sanguinet and the Messer brothers, there was life—and a living—outside Arlington Heights. In 1892 they designed two ward schools. The Sixth Ward school building survives on Lipscomb Street.

In 1909 a twin of the 1892 building was built on the north end, doubling the school’s size.

The Seventh Ward school building (identical to the Sixth Ward school building) was on East Magnolia Avenue between Louisiana and Evans streets. Today the South Freeway covers the site. (Photo from FWISD Billy W. Sills Center for Archives.)

The Seventh Ward school building (identical to the Sixth Ward school building) was on East Magnolia Avenue between Louisiana and Evans streets. Today the South Freeway covers the site. (Photo from FWISD Billy W. Sills Center for Archives.)

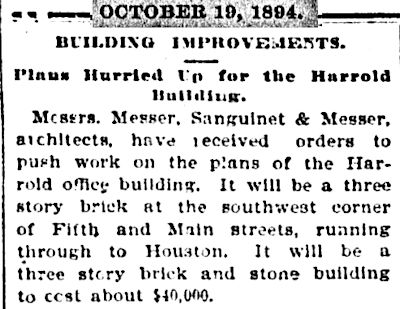

In 1894 the firm of MS&M designed the Harrold Building, built by capitalists E. B. Harrold and Winfield Scott. The building was the home of The Fair department store from 1895 to 1930. (Photo from UTA Library Special Collections Digital Galleries.)

In 1894 the firm of MS&M designed the Harrold Building, built by capitalists E. B. Harrold and Winfield Scott. The building was the home of The Fair department store from 1895 to 1930. (Photo from UTA Library Special Collections Digital Galleries.)

But Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer weren’t too big to think small. In 1892 they designed a horse trough and fountain for the courthouse square, erected by the Women’s Humane Association. The horse trough and fountain were reconstructed in 1999.

But Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer weren’t too big to think small. In 1892 they designed a horse trough and fountain for the courthouse square, erected by the Women’s Humane Association. The horse trough and fountain were reconstructed in 1999.

In 1893 MS&M designed another horse trough and fountain: the monument to Al Hayne, hero of the 1890 Texas Spring Palace fire. And, yes, Mrs. H. W. Tallant was the wife of Henry W. Tallant of the Chamberlin company.

In 1893 MS&M designed another horse trough and fountain: the monument to Al Hayne, hero of the 1890 Texas Spring Palace fire. And, yes, Mrs. H. W. Tallant was the wife of Henry W. Tallant of the Chamberlin company.

In 1896 the Messer brothers ended their partnership with Marshall Sanguinet, who in 1903 would partner with Carl Staats to form one of Fort Worth’s premier architectural firms.

In 1898 Arthur Messer returned to England.

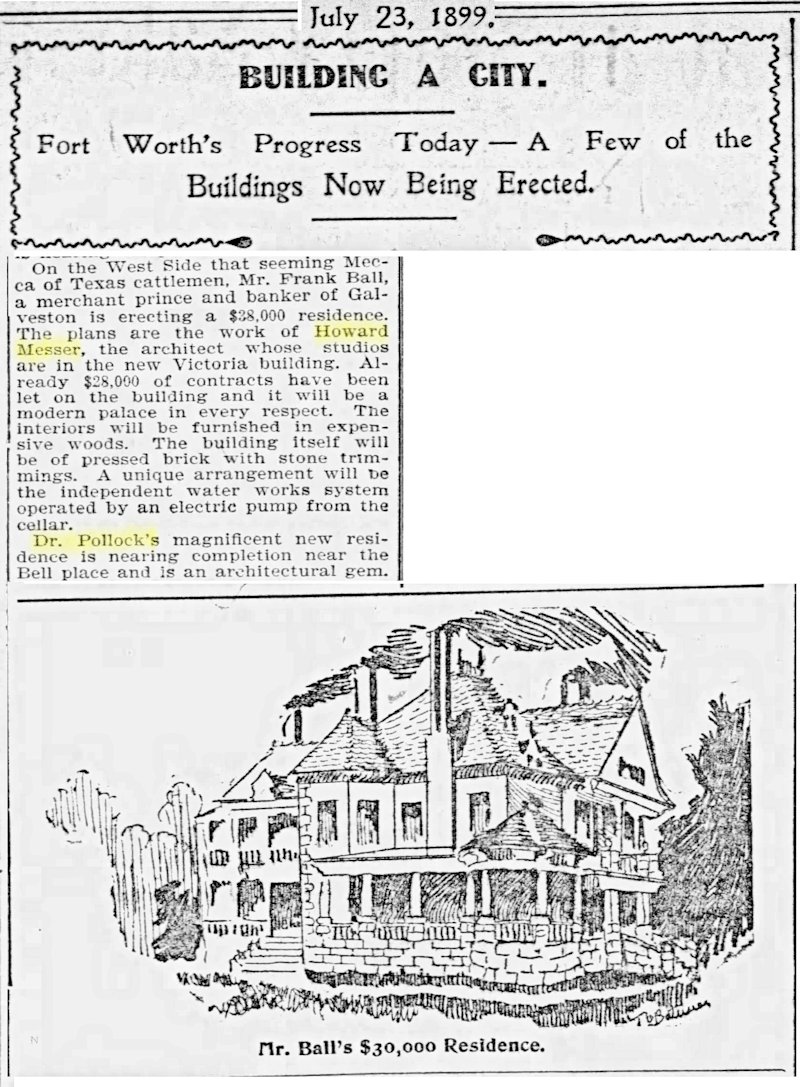

The next year, 1899, was prolific for Howard Messer. For starters, he designed the Quality Hill mansion of Sarah C. Ball, widow of Galveston banker George Ball, and her son Frank, a Fort Worth capitalist.

Note that the newspaper mentioned the Pollock mansion being built next door but did not name its architect. Some historians think Howard Messer designed both houses.

Note that the newspaper mentioned the Pollock mansion being built next door but did not name its architect. Some historians think Howard Messer designed both houses.

After Andrew Carnegie funded a public library for Fort Worth, Messer was named “consulting local architect,” which probably means that Carnegie employed his own architect to design the many public libraries that Carnegie funded and relied on local architects to carry out the design “on the ground.”

After Andrew Carnegie funded a public library for Fort Worth, Messer was named “consulting local architect,” which probably means that Carnegie employed his own architect to design the many public libraries that Carnegie funded and relied on local architects to carry out the design “on the ground.”

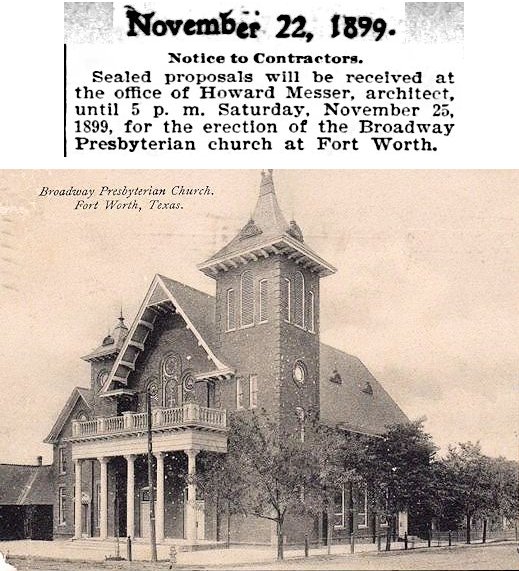

Messer also designed the Broadway Presbyterian Church building. The building was located just north of Broadway Baptist Church. Broadway Presbyterian Church was destroyed in the South Side fire of 1909. (Postcard courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

Messer also designed the Broadway Presbyterian Church building. The building was located just north of Broadway Baptist Church. Broadway Presbyterian Church was destroyed in the South Side fire of 1909. (Postcard courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

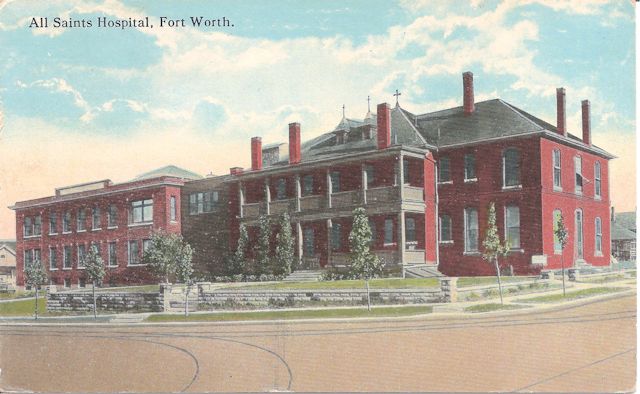

Messer also designed the original building of All Saints Hospital. The cornerstone was laid in 1900.

Messer also designed the original building of All Saints Hospital. The cornerstone was laid in 1900.

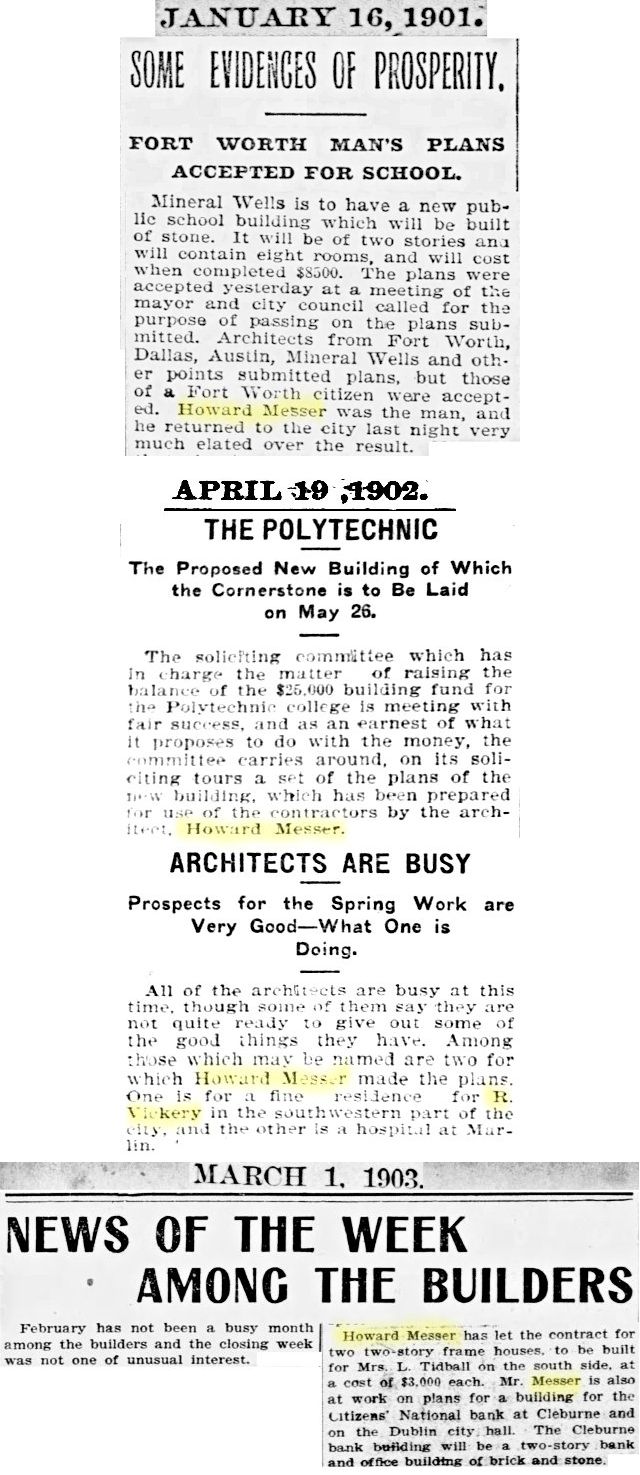

Among Messer’s other projects as the new century began were a school building in Mineral Wells, a bank in Cleburne, the city hall in Dublin, a building at Polytechnic College, and houses for R. Vickery and Lelia Tidball, widow of pioneer banker T. A. Tidball.

Among Messer’s other projects as the new century began were a school building in Mineral Wells, a bank in Cleburne, the city hall in Dublin, a building at Polytechnic College, and houses for R. Vickery and Lelia Tidball, widow of pioneer banker T. A. Tidball.

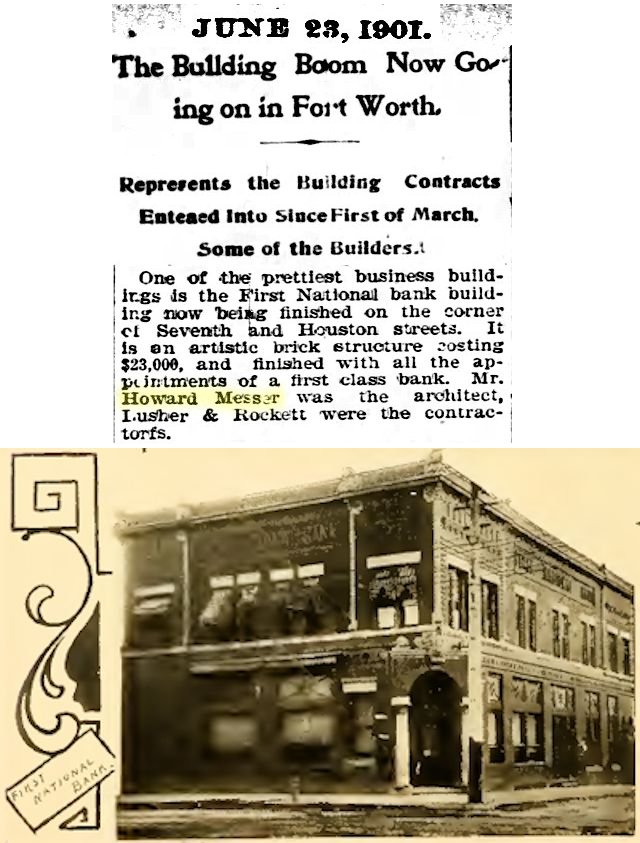

Messer also designed First National Bank’s second home on Houston Street at West 7th Street. (Image from Greater Fort Worth, 1907.)

Messer also designed First National Bank’s second home on Houston Street at West 7th Street. (Image from Greater Fort Worth, 1907.)

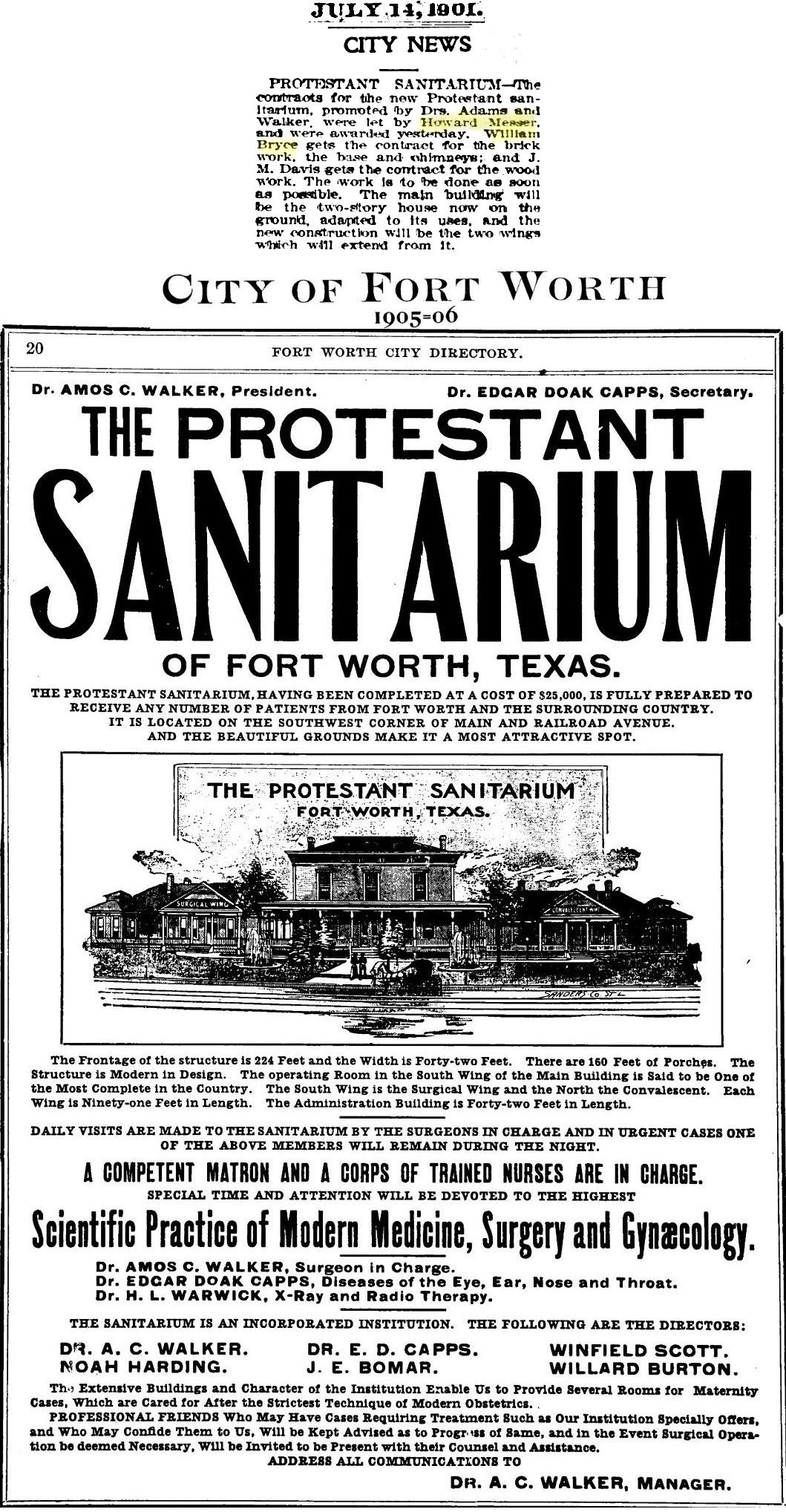

And when Dr. Amos C. Walker expanded his Protestant Sanitarium, Messer designed the two new wings. (The original building of the sanitarium had been the home of General J. J. Bryne.) William Bryce was the masonry contractor for the expansion. The sanitarium was located at the corner of Main Street and Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard). Like Broadway Presbyterian Church, the sanitarium burned in the South Side fire.

And when Dr. Amos C. Walker expanded his Protestant Sanitarium, Messer designed the two new wings. (The original building of the sanitarium had been the home of General J. J. Bryne.) William Bryce was the masonry contractor for the expansion. The sanitarium was located at the corner of Main Street and Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard). Like Broadway Presbyterian Church, the sanitarium burned in the South Side fire.

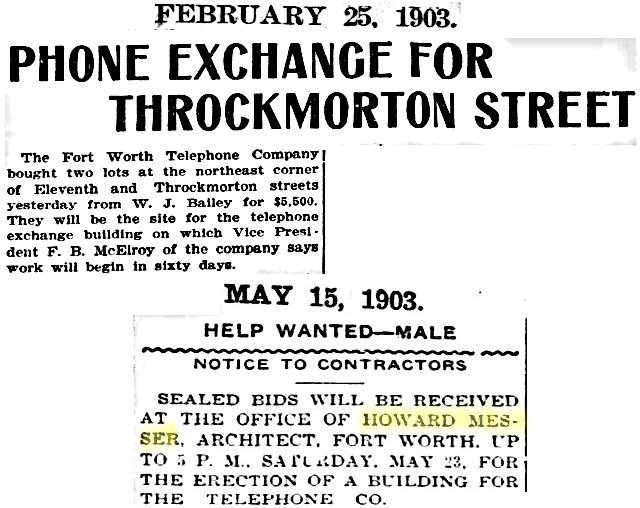

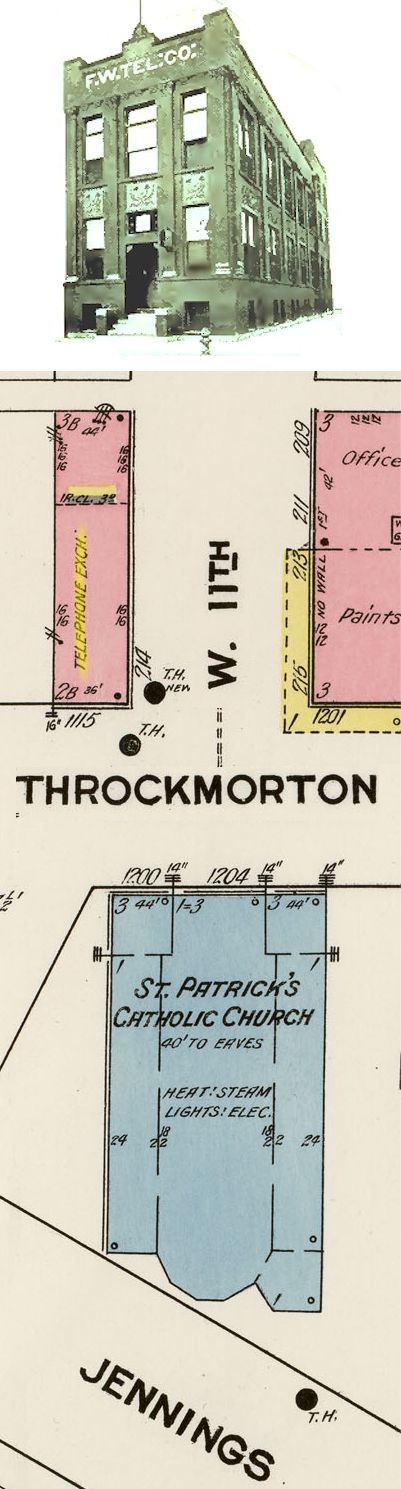

In 1903 the telephone company bought two lots on Throckmorton Street at West 11th Street from William J. Bailey and hired Messer to design a new building. Today the telephone company is still located where it was in 1903.

In 1903 the telephone company bought two lots on Throckmorton Street at West 11th Street from William J. Bailey and hired Messer to design a new building. Today the telephone company is still located where it was in 1903.

In 1905 Howard Messer followed his brother back to England. Two years later All Saints Hospital was finally finished. The original building is on the right. On the left is an addition built in 1913. Note the streetcar tracks. (Postcard from Barbara Love Logan.)

In 1905 Howard Messer followed his brother back to England. Two years later All Saints Hospital was finally finished. The original building is on the right. On the left is an addition built in 1913. Note the streetcar tracks. (Postcard from Barbara Love Logan.)

In England the brothers Messer continued to practice architecture. But Arthur Messer also served as a major in the British Army during World War I and became director of Graves Registration and Enquiries, a British Army department tasked with preserving records of burials and providing the means for graves to be identified and marked.

Arthur Messer was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Chevalier, Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest order of merit. He also was awarded the title of CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire).

Arthur Albert Messer died in 1934 at age seventy. He is buried in Brookwood Cemetery (the London Necropolis), the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom. Messer designed two chapels in the cemetery he was buried in.

Howard Messer died in England in 1950 at age eighty-nine.

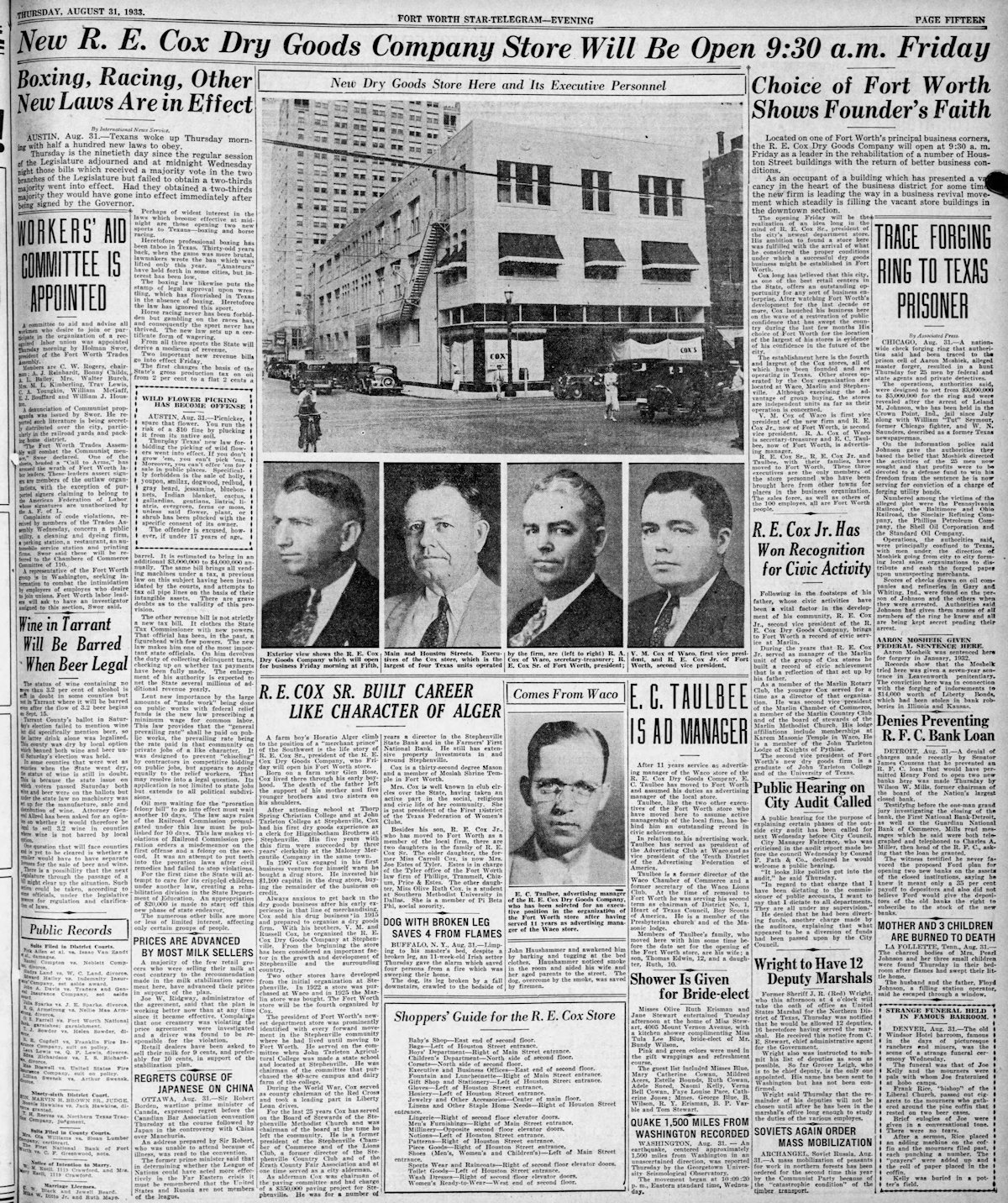

In 1933 Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer’s 1895 Harrold Building became the first home of R. E. Cox department store in Fort Worth. The building’s exterior had been given a radical modernization designed by architect Wiley Clarkson. The ornate brick-and-stone architecture of the 1890s—the parapets and bay windows—was removed, and the exterior was covered by a stucco façade.

In 1933 Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer’s 1895 Harrold Building became the first home of R. E. Cox department store in Fort Worth. The building’s exterior had been given a radical modernization designed by architect Wiley Clarkson. The ornate brick-and-stone architecture of the 1890s—the parapets and bay windows—was removed, and the exterior was covered by a stucco façade.

This was the 1890 Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer model house in Arlington Heights in 1941. For years it had been the home of Robert McCart. It survived into the 1970s. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

And this was the 1890 Harrold Building in 1946 before yet another makeover removed even the windows (photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library). The building housed the Lerner Shop from 1947 until 1986. To the left can be seen the 1915 Fort Worth Club Building (Ken Davis’s Mid-Continent Supply Company at the time, now the Ashton Hotel), the 1890 Winfree Building (second location of the White Elephant), and the Kress Building. The Harrold Building was torn down in 1996 at age 101—a long life for a building in downtown Fort Worth. The building was replaced by . . . wait for it . . .

And this was the 1890 Harrold Building in 1946 before yet another makeover removed even the windows (photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library). The building housed the Lerner Shop from 1947 until 1986. To the left can be seen the 1915 Fort Worth Club Building (Ken Davis’s Mid-Continent Supply Company at the time, now the Ashton Hotel), the 1890 Winfree Building (second location of the White Elephant), and the Kress Building. The Harrold Building was torn down in 1996 at age 101—a long life for a building in downtown Fort Worth. The building was replaced by . . . wait for it . . .

a parking lot. In 2020 the fifty-foot-wide parking lot was replaced by the AC Hotel Fort Worth Downtown.