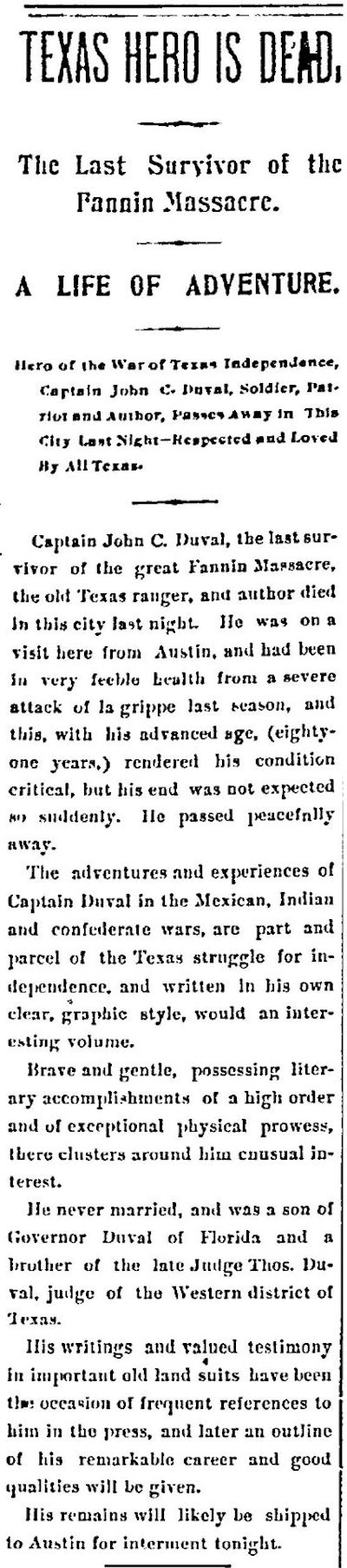

On January 16, 1897 readers of the Fort Worth Register read that one of the most remarkable lives in early Texas history had ended in Fort Worth the previous night.

John Crittenden Duval was the last survivor of the Goliad Massacre.

John Crittenden Duval was the last survivor of the Goliad Massacre.

Duval was born in Kentucky in 1816. In 1835 he left college to join a company of soldiers organized by his brother, Burr H. Duval, to help Texas in its fight for independence from Mexico. The two brothers were soldiers in Colonel James Fannin’s army when it surrendered at the Battle of Coleto after being outmatched by General José de Urrea’s Mexican forces on March 20, 1836. Fannin had surrendered with the understanding that his men would be considered prisoners of war, given medical attention, and eventually “paroled” to the United States.

Urrea’s men marched Fannin and his men to the fort of Goliad—which Fannin had previously occupied—and imprisoned them in the chapel.

Then came March 27—Palm Sunday. The Alamo had fallen three weeks earlier. Sam Houston’s victory at San Jacinto was still three long weeks in the future.

But Fannin and more than three hundred of his men would have no future.

At sunrise Mexican soldiers marched those prisoners who could walk out to the road and shot them. Those prisoners who could not walk and who had remained at the fort of Goliad—including Fannin—also were executed. By one estimate 342 men were killed. Only twenty-eight men escaped. Another twenty men who had some useful skill were spared largely because of the entreaties of Francita Alavez, who has become known in Texas history as the “Angel of Goliad.”

On that Palm Sunday Burr Duval was among the 342.

But brother John Duval was among the twenty-eight.

John wrote of his escape in his Early Times in Texas or, the Adventures of Jack Dobell (1892). Here is an excerpt:

On the morning of the 27th of March, a Mexican officer came to us, and ordered us to get ready for a march. He told us we were to be liberated on “parole,” and that arrangements had been made to send us to New Orleans on board of vessels then at Copano. . . . When all was ready we were formed into three divisions and marched out under a strong guard . . . When about a mile above town, a halt was made and the guard on the side next the river filed around to the opposite side. Hardly had this maneuver been executed, when I heard a heavy firing of musketry in the directions taken by the other two divisions.

Some one near me exclaimed “Boys! they are going to shoot us!” and at the same instant I heard the clicking of musket locks all along the Mexican line. I turned to look, and as I did so, the Mexicans fired upon us, killing probably one hundred out of the one hundred and fifty men in the division. We were in the double file and I was in the rear rank. The man in front of me was shot dead, and in falling he knocked me down. I didn’t get up for a minute, and when I rose to my feet, I found that the whole Mexican line had charged over me, and were in hot pursuit of those who had not been shot and who were fleeing towards the river about five hundred yards distant. I followed on after them, for I knew that escape in any direction (all open prairie) would be impossible, and I had nearly reached the river before it became necessary to make my way through the Mexican line ahead. . . . I hastened to the bank of the river and plunged in. The river at that point was deep and swift, but not wide, and being a good swimmer, I soon gained the opposite bank, untouched by any of the bullets that were pattering in the water around my head. . . . I continued to swim down the river until I came to where a grape vine hung from the bough of a leaning tree nearly to the surface of the water. This I caught hold of and was climbing up it hand over hand, sailor fashion, when a Mexican on the opposite bank fired at me with his escopeta [muzzle-loading musket or carbine], and with so true an aim, that he cut the vine in two just above my head, and down I came into the water again. I then swam on about a hundred yards further, when I came to a place where the bank was not quite so steep, and with some difficulty I managed to clamber up.

The river on the north side was bordered by timber several hundred yards in width, through which I quickly passed and I was just about to leave it and strike out into the open prairie, when I discovered a party of lancers nearly in front of me, sitting on their horses, evidently stationed there to intercept any one who should attempt to escape in that direction. I halted at once under the cover of the timber, through which I could see the lancers in the open prairie, but which hid me entirely from their view.

Duval then came across two other escapees, and the three men encountered yet more threats to their lives:

We traveled about five or six miles and stopped in a thick grove to rest ourselves, where we staid until night. All day long we heard at intervals irregular discharges of musketry in the distance, indicating, as we supposed, where fugitives from the massacre were overtaken and shot by the pursuing parties of Mexicans. . . . In talking the matter over and reflecting upon the many narrow risks we had run in making our escape, we came to the conclusion that in all probability we were the only survivors of the hundreds who had that morning been led out to slaughter; although in fact as we subsequently learned, twenty-five or thirty of our men eventually reached the settlements on the Brazos.

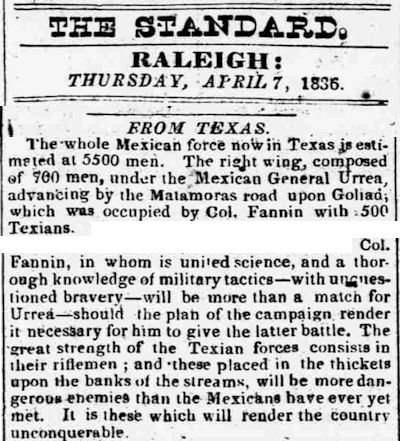

In this age of instant news updates, it is difficult to conceive of how slowly news traveled in 1836. The Raleigh Standard of April 7 not only was not yet aware of the massacre but also was optimistic that Mexico’s General Urrea was no match for Fannin and “the Texian forces.”

In this age of instant news updates, it is difficult to conceive of how slowly news traveled in 1836. The Raleigh Standard of April 7 not only was not yet aware of the massacre but also was optimistic that Mexico’s General Urrea was no match for Fannin and “the Texian forces.”

Colonel James Fannin (photo from Wikipedia).

Colonel James Fannin (photo from Wikipedia).

General José de Urrea (photo from Wikipedia).

General José de Urrea (photo from Wikipedia).

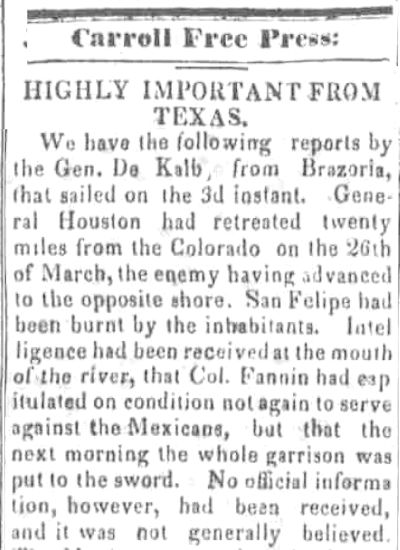

Even by May 6 the Carroll Free Press (Ohio) had not confirmed the massacre.

Even by May 6 the Carroll Free Press (Ohio) had not confirmed the massacre.

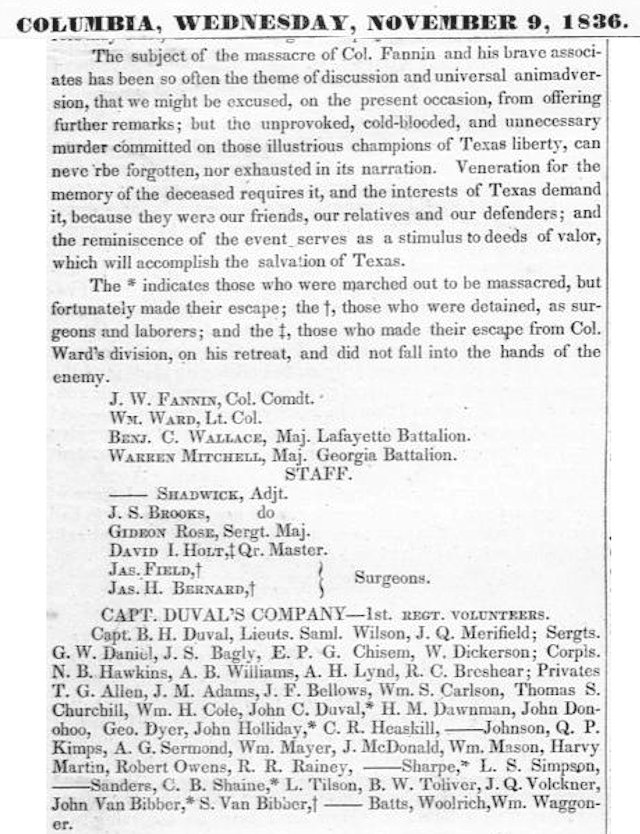

On November 9, 1836 the Telegraph and Texas Register of Columbia listed the Texians who were killed, spared, or escaped at Goliad. This clip includes the Duval brothers. Asterisks indicate the men who escaped.

On November 9, 1836 the Telegraph and Texas Register of Columbia listed the Texians who were killed, spared, or escaped at Goliad. This clip includes the Duval brothers. Asterisks indicate the men who escaped.

Colonel Fannin was the last Texian to be executed. He was blindfolded and seated in a chair in a courtyard at Goliad. Fannin made three requests: that his personal possessions be sent to his family, that he be shot in the heart, not the face, and that he be given a Christian burial. All three requests were denied. His body was burned along with the other Texians who died in the massacre.

In the clip above, see the name “R. R. Rainey” in the fourth line from the bottom? That surely is R. R. Ramey, who died fighting with Fannin. For Ramey’s service, his heirs were given a tract of land in what became the Englewood Heights addition in south Poly. The tract of land today includes Ramey Street. More on the history of the R. R. Ramey tract.

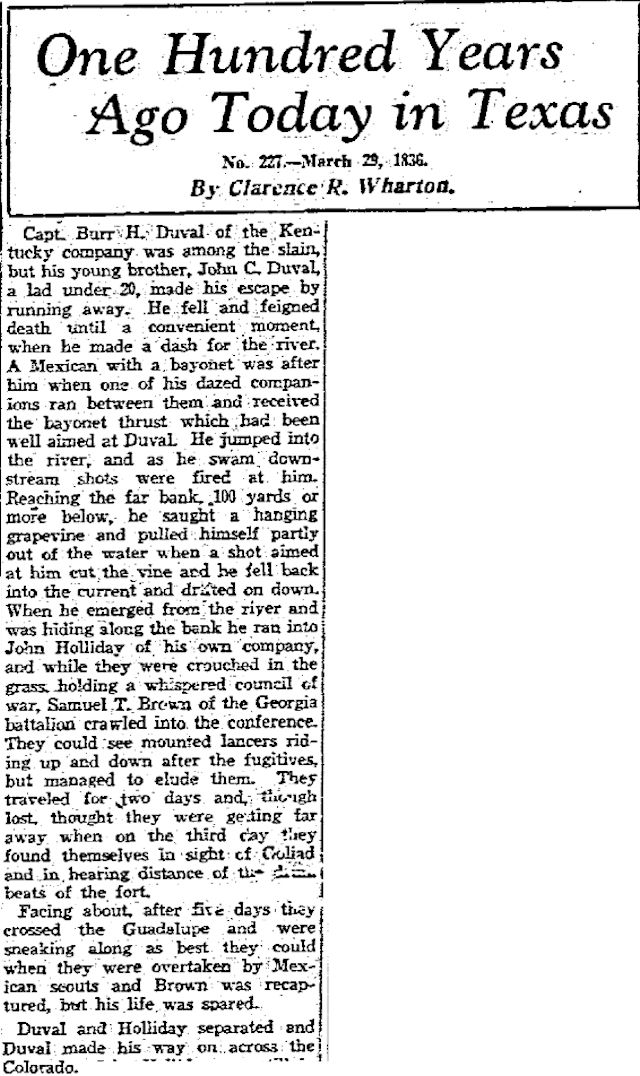

On the centennial of the massacre, the Dallas Morning News printed a retelling of Duval’s escape. Clip is from March 29, 1936.

On the centennial of the massacre, the Dallas Morning News printed a retelling of Duval’s escape. Clip is from March 29, 1936.

After his escape from Goliad Duval went back east and studied engineering at the University of Virginia. But he returned to Texas by 1840 and became a surveyor. Then came the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Duval fought under Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott (not “our” Winfield Scott). Then Duval served with two more Texas legends—William A. “Bigfoot” Wallace and John Coffee Hays—as a Texas Ranger. (Wallace had lost a brother and a cousin at Goliad.)

Then came the Civil War, and Duval joined the Confederate Army to fight in his third war in twenty-six years. He was forty-five years old.

Then the man who had seen so many die by the sword began to live by the pen.

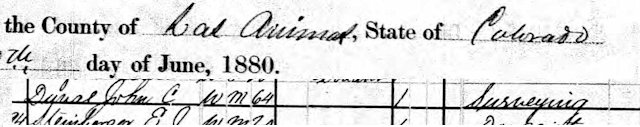

Duval was comfortable being alone and comfortable being outdoors. As he worked as a surveyor of frontier territory, he began to write about his life, recalling remarkable people and remarkable events. Clip is from the Las Animas County, Colorado 1880 census.

Duval was comfortable being alone and comfortable being outdoors. As he worked as a surveyor of frontier territory, he began to write about his life, recalling remarkable people and remarkable events. Clip is from the Las Animas County, Colorado 1880 census.

Texas folklorist J. Frank Dobie, who wrote a biography of Duval (John C. Duval: First Texas Man of Letters, 1939), called him the “father of Texas literature.”

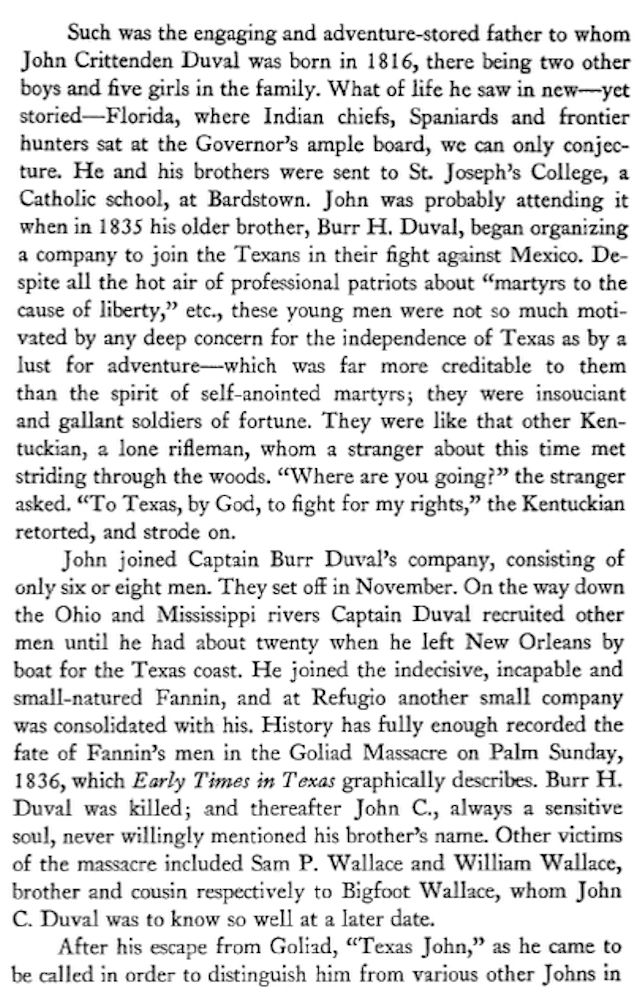

An excerpt from Dobie’s John C. Duval: First Texas Man of Letters.

An excerpt from Dobie’s John C. Duval: First Texas Man of Letters.

In addition to Early Times in Texas, Duval wrote The Adventures of Big-Foot Wallace, the Texas Ranger and Hunter (1870) and The Young Explorers (1890s), a sequel to Early Times in Texas.

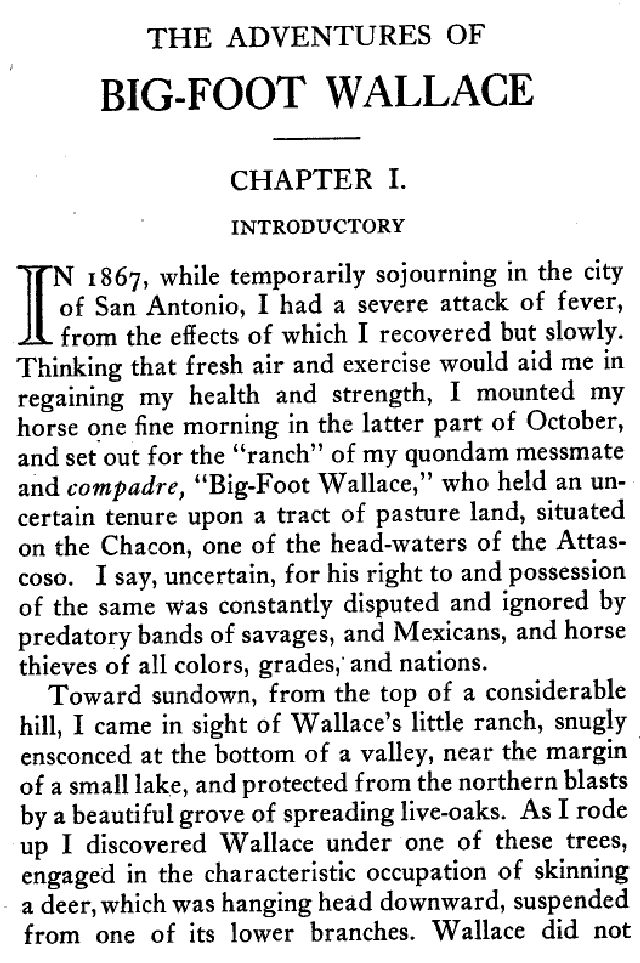

An excerpt from The Adventures of Big-Foot Wallace.

An excerpt from The Adventures of Big-Foot Wallace.

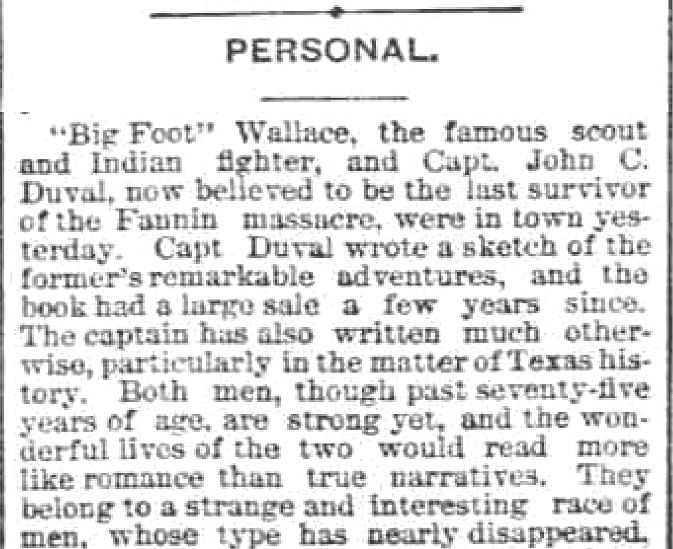

Wallace and Duval were in Fort Worth in 1891. Clip is from the April 12 Gazette.

Wallace and Duval were in Fort Worth in 1891. Clip is from the April 12 Gazette.

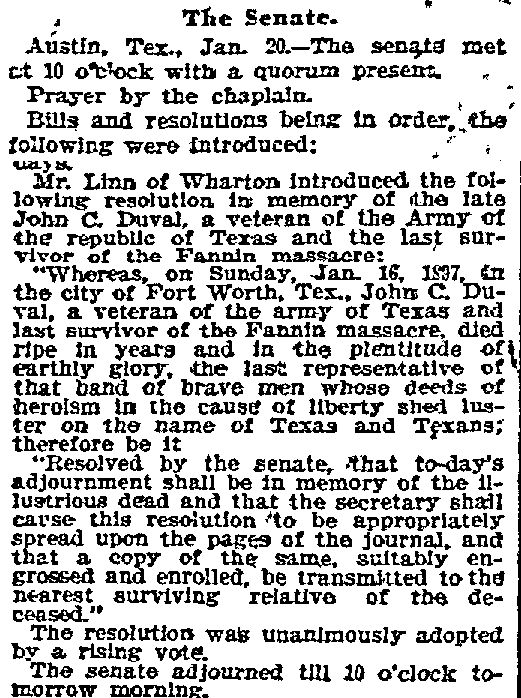

After Duval’s death on January 15, 1897 the Texas Senate passed a resolution honoring him. Clip is from the January 21 Dallas Morning News.

After Duval’s death on January 15, 1897 the Texas Senate passed a resolution honoring him. Clip is from the January 21 Dallas Morning News.

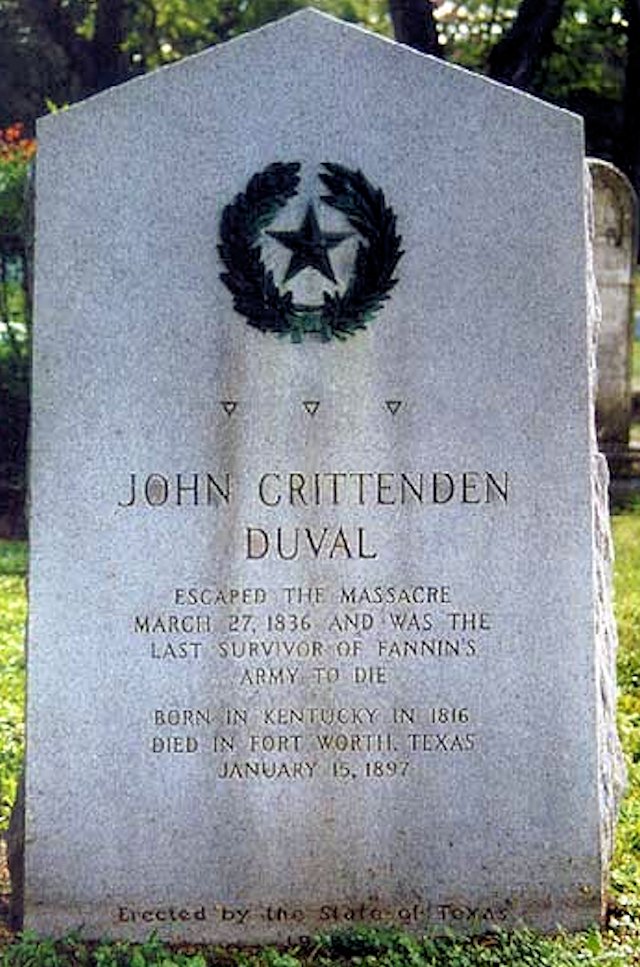

John Crittenden Duval is buried in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery. Another brother, Thomas Howard, was a federal judge in Texas. Duval County is named for the three brothers, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

John Crittenden Duval is buried in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery. Another brother, Thomas Howard, was a federal judge in Texas. Duval County is named for the three brothers, according to the Texas State Historical Association.