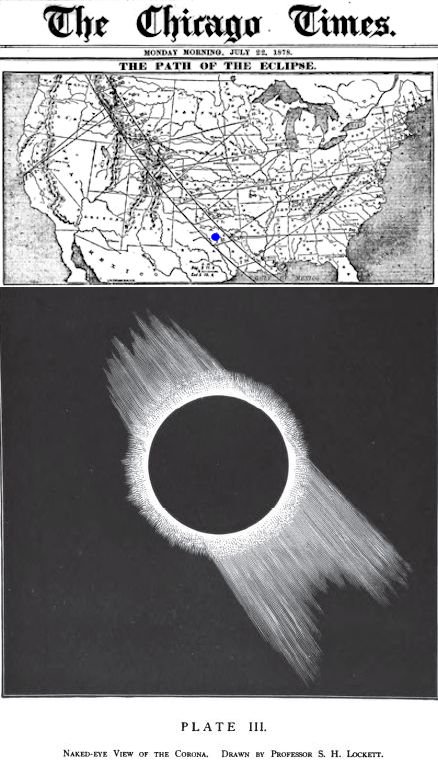

Once upon a time in the West, Fort Worth was smack dab in the path of a total solar eclipse.

And that serendipitous alignment earned Fort Worth (blue dot on Chicago Times map) a bright moment of celebrity. Well, a dark moment of celebrity, to be precise.

And that serendipitous alignment earned Fort Worth (blue dot on Chicago Times map) a bright moment of celebrity. Well, a dark moment of celebrity, to be precise.

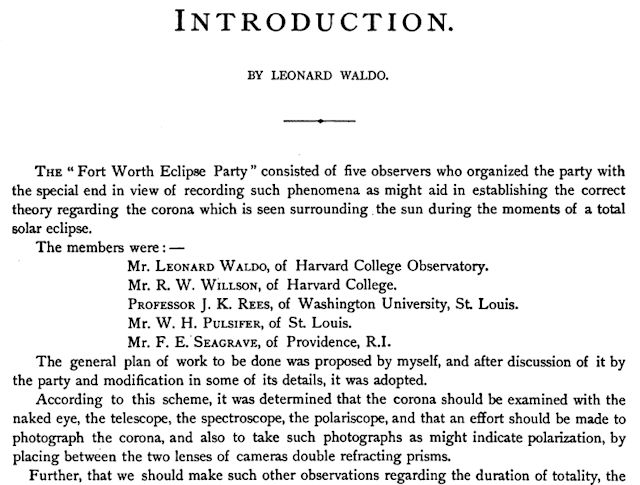

And “precise” describes the five men who stepped off the train in Fort Worth at the passenger depot on July 18, 1878. The five men were laden with enough crates to outfit a safari. And that’s exactly what the men were on—a celestial safari.

The five men were Leonard Waldo, astronomer, Harvard University; R. W. Willson, professor of astronomy, Harvard University; W. H. Pulsifer, astronomer, St. Louis; J. K. Rees, professor of math and astronomy, Washington University, St. Louis; and F. E. Seagrave, astronomer, Providence, Rhode Island.

The five men were Leonard Waldo, astronomer, Harvard University; R. W. Willson, professor of astronomy, Harvard University; W. H. Pulsifer, astronomer, St. Louis; J. K. Rees, professor of math and astronomy, Washington University, St. Louis; and F. E. Seagrave, astronomer, Providence, Rhode Island.

Yep, y’all, eggheads from back east. Come to Cowtown to take a gander at the sky on July 29, 1878 as the moon, well, mooned the sun. (Photo of Leonard Waldo later in life from Arizona State University.)

Some national context: In 1878 the sun shone down upon an America with a population of about forty-eight million people scattered across thirty-eight states. Rutherford B. Hayes was president. That year the Remington company introduced a typewriter with a shift key, allowing both uppercase and lowercase letters. Tom Sawyer had been in print only two years. Pancho Villa, Lionel Barrymore, George M. Cohan, Joseph Stalin, and Louis Chevrolet were born. Sam Bass was killed. In major league baseball’s only league, the six teams of the National League (itself only two years old) were in Boston, Cincinnati, Providence, Chicago, Indianapolis, and Milwaukee. Paul Hines of Providence led the league with four home runs.

Some local context: In 1878 the sun shone down upon a Fort Worth with a population of about seven thousand, many of those people having arrived in the boom that had begun with arrival of the Texas & Pacific railroad in 1876. Most of the population lived in today’s downtown area.

Some local context: In 1878 the sun shone down upon a Fort Worth with a population of about seven thousand, many of those people having arrived in the boom that had begun with arrival of the Texas & Pacific railroad in 1876. Most of the population lived in today’s downtown area.

In 1878 Fort Worth had been incorporated only five years. Mayor was R. E. Beckham. City marshal was Jim Courtright. Courtright also was first assistant of the M. T. Johnson Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 of the volunteer fire department.

The streets of Cowtown were unpaved: muddy in spring, dusty in summer. Houses had no indoor plumbing: Residents fetched water from wells, cisterns, the river. No electricity. A few streets had gas lights, and a few businesses had piped gas. Brothels were common, especially in Hell’s Half Acre. Only one day before the five scientists from back east arrived in town, the city council had passed an ordinance prohibiting the “running at large” of domestic “hogs, shoats, and pigs.” Architecturally, most buildings in town were wooden. So were the sidewalks. It was a world of outhouses, spittoons, and hitching posts.

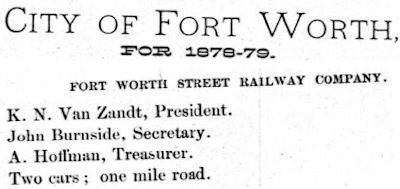

Also in service only two years by 1878 was Fort Worth Street Railway Company, headed by the ubiquitous Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. The streetcar line still had only two mule-drawn cars and one mile of track between the courthouse and the Texas & Pacific passenger depot.

Also in service only two years by 1878 was Fort Worth Street Railway Company, headed by the ubiquitous Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. The streetcar line still had only two mule-drawn cars and one mile of track between the courthouse and the Texas & Pacific passenger depot.

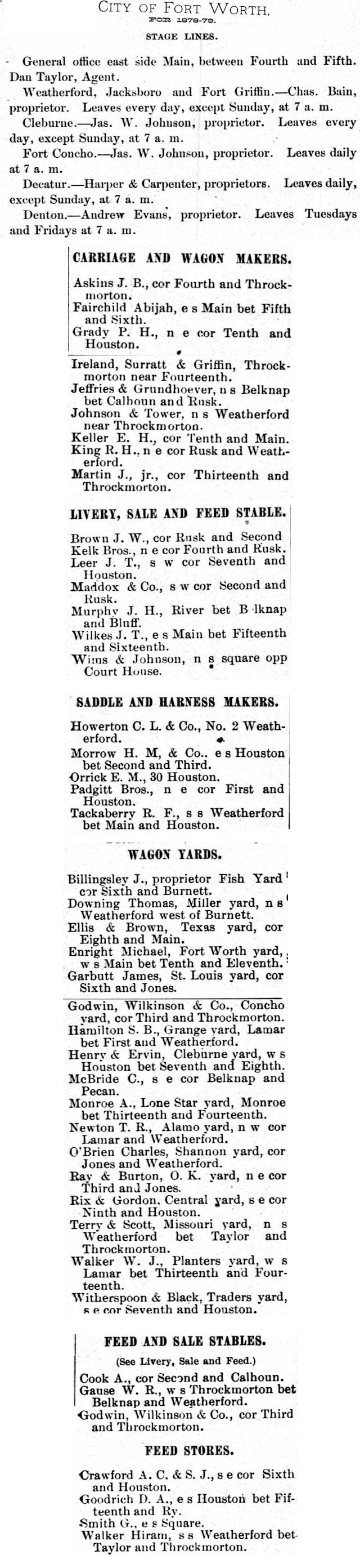

Despite the railroad and the modest streetcar line, to most people in 1878 “rapid transit” meant a horse or a conveyance drawn by a horse. For example, Fort Worth was served by five stage coach lines. In an equinecentric world people needed carriage and wagon makers, livery stables, wagon yards, saddle and harness makers, feed stores. Among the carriage makers was Ewald Henry Keller, who early in the twentieth century would reinvent himself as an automobile repairman. Among the feed and sale stable operators was W. R. Gause, father of George Gause, who the next year would become Fort Worth’s first formally trained undertaker.

Despite the railroad and the modest streetcar line, to most people in 1878 “rapid transit” meant a horse or a conveyance drawn by a horse. For example, Fort Worth was served by five stage coach lines. In an equinecentric world people needed carriage and wagon makers, livery stables, wagon yards, saddle and harness makers, feed stores. Among the carriage makers was Ewald Henry Keller, who early in the twentieth century would reinvent himself as an automobile repairman. Among the feed and sale stable operators was W. R. Gause, father of George Gause, who the next year would become Fort Worth’s first formally trained undertaker.

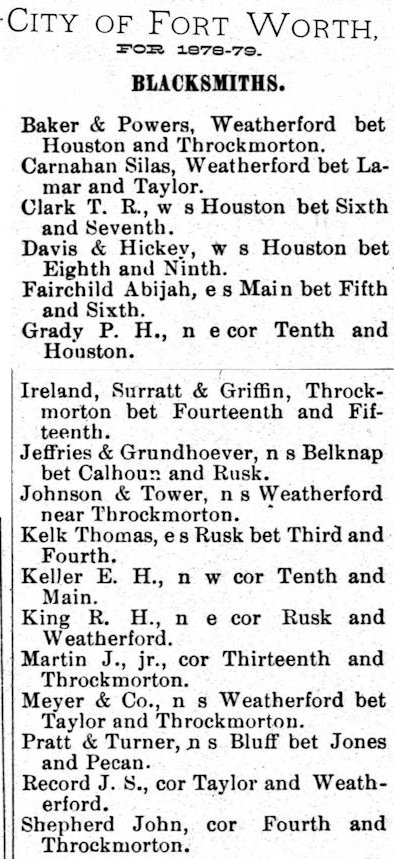

All those horses needed shoes. Fort Worth had seventeen blacksmiths.

All those horses needed shoes. Fort Worth had seventeen blacksmiths.

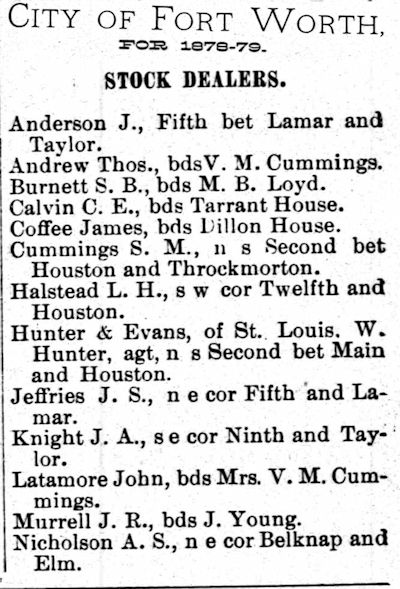

And even though Fort Worth would not have its first stockyards until 1889, the city already was very much a cow town because of the cattle drives that passed through. Note that one of the stock dealers in 1878 was Samuel Burk Burnett, who boarded with father-in-law Martin Bottom Loyd.

And even though Fort Worth would not have its first stockyards until 1889, the city already was very much a cow town because of the cattle drives that passed through. Note that one of the stock dealers in 1878 was Samuel Burk Burnett, who boarded with father-in-law Martin Bottom Loyd.

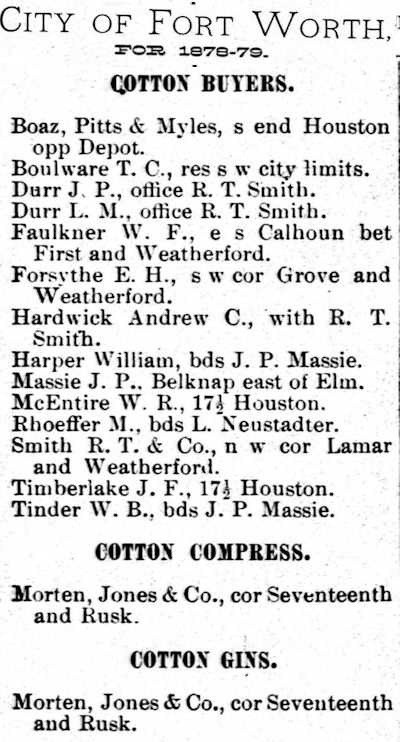

In 1878 cotton was still king.

In 1878 cotton was still king.

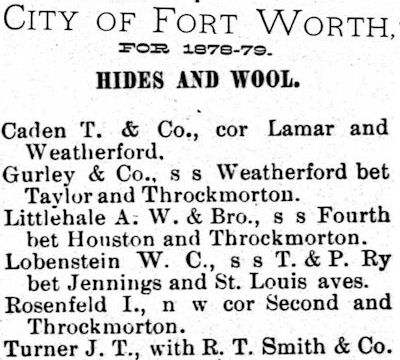

Hides and wool also were important commodities. The city directory boasted of the “enormous stocks of the buffalo hide ever arriving” in town.

Hides and wool also were important commodities. The city directory boasted of the “enormous stocks of the buffalo hide ever arriving” in town.

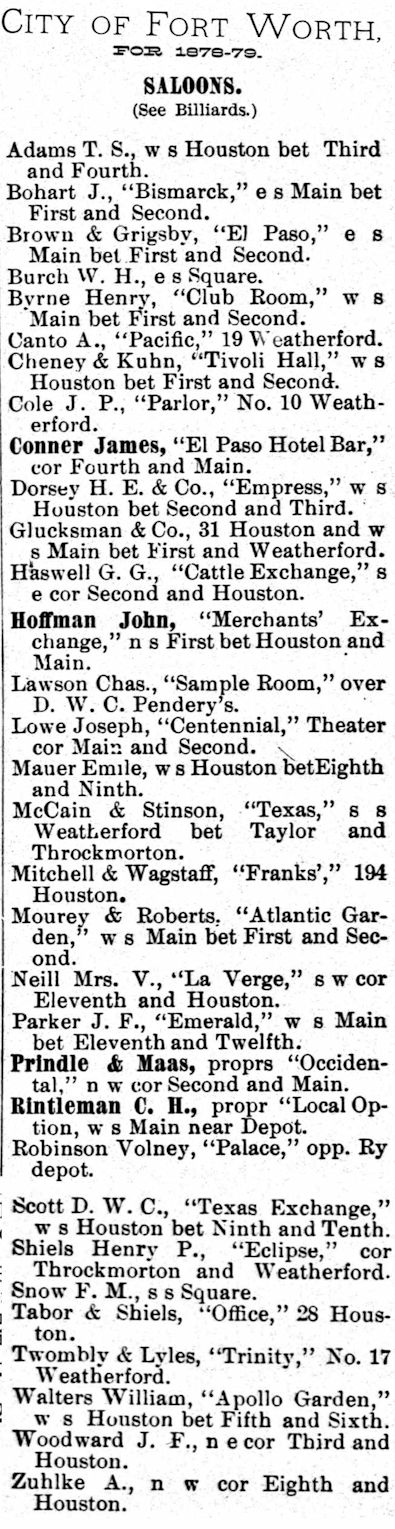

Fort Worth had thirty-two saloons (including the Eclipse) . . .

Fort Worth had thirty-two saloons (including the Eclipse) . . .

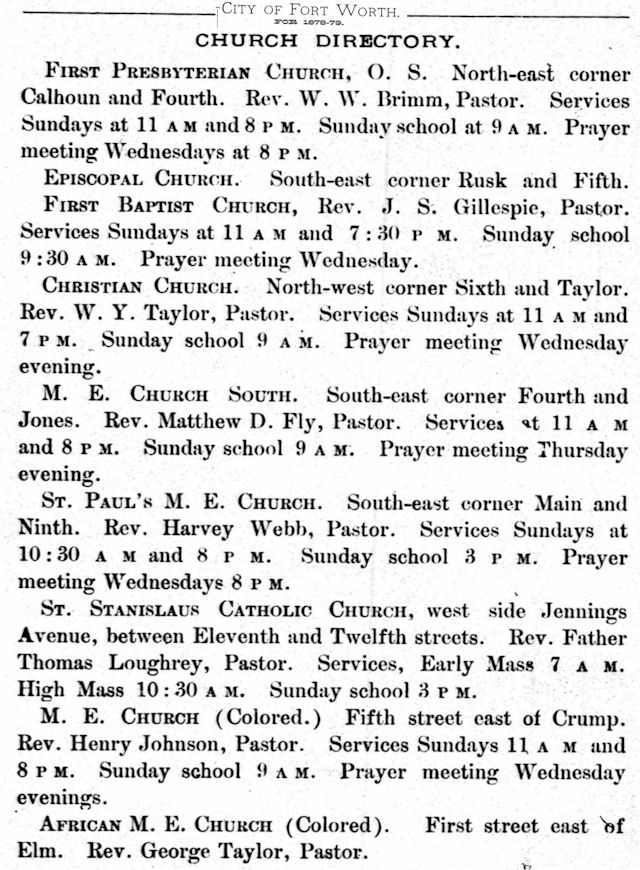

but only nine churches, including First Baptist, St. Stanislaus Catholic, Methodist Episcopal Church South, and First Christian.

but only nine churches, including First Baptist, St. Stanislaus Catholic, Methodist Episcopal Church South, and First Christian.

Likewise, Fort Worth had nine schools—one parochial, eight private. A public school system would not begin classes until 1882.

Fort Worth had two militia units (Tarrant Rifles and Trinity Guards), four “secret and benevolent societies” (Masons, Knights of Pythias, Odd Fellows, and B’nai B’rith), and one temperance society.

The city had a dozen physicians but would not have a hospital until 1885.

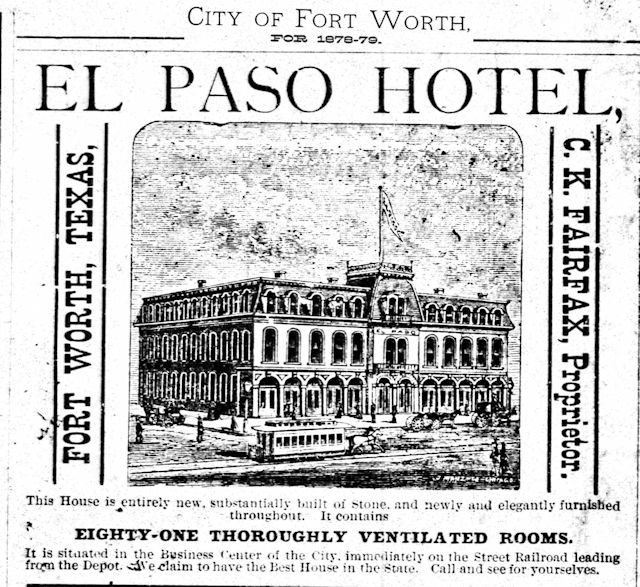

Fort Worth had a few hotels, but the new El Paso Hotel, the 1878 city directory boasted, was a “monument to the liberality of our public spirited citizens.” The El Paso was the city’s first three-story building.

Fort Worth had a few hotels, but the new El Paso Hotel, the 1878 city directory boasted, was a “monument to the liberality of our public spirited citizens.” The El Paso was the city’s first three-story building.

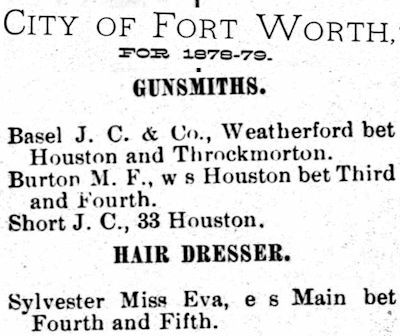

Fort Worth had three gunsmiths and one hair dresser.

Fort Worth had three gunsmiths and one hair dresser.

That was the Cowtown that the five scientists from back east experienced during the eleven days they were in town. Imagine the culture shock for both Cowtown and the scientists, especially the two from Boston’s Harvard University. After all, Boston was east, and Fort Worth was west. Boston, founded in 1630, was a port town connected to the rest of the world by ships. Fort Worth, founded in 1849, was a frontier town that had been served by a single railroad just two years. Boston had a population of more than three hundred thousand; Fort Worth had about seven thousand. By 1878 the Boston area had twelve colleges. Fort Worth would not have its first college until 1881.

In short, Boston was cosmopolitan; Fort Worth was cowsmopolitan.

People of Boston and Fort Worth talked and dressed differently, had different backgrounds and lifestyles. Fort Worth, of course, was settled by pioneers from back east, including some from Boston, but by 1878 a fair share of Fort Worth’s population had been born here. Cowtown had developed its own identity as a wild West town.

And what did the five scientists from back east, bristling with telescopes, think of that wild West town when they stepped off the train? What did they think when they saw men packing guns on the street? Sure, city ordinance prohibited carrying guns, but the ordinance was laxly enforced, trumped by the Code of the West—a fact attested to by the amount of gunplay in Hell’s Half Acre on a Saturday night.

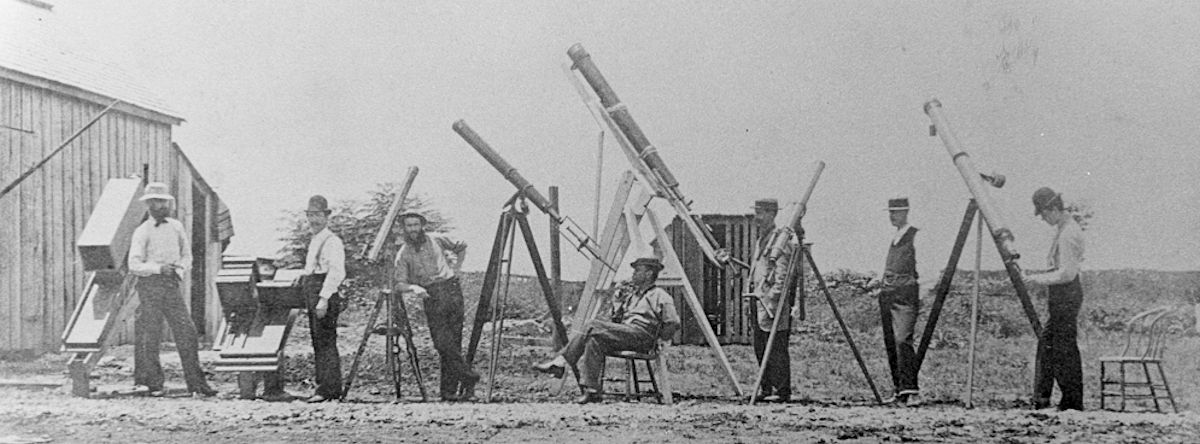

And how about Jim Courtright and the rest of the Cowtown cowboys? When they saw those five eastern eggheads packin’ those great long telescopes, did they suffer a twinge of instrument envy? Some of those telescopes were taller than a man (see photo below) and appeared like cannons in comparison with the Colt revolvers and Winchester rifles and the occasional Sharps buffalo rifles that were toted around Cowtown.

Oh, to have been privy to the thoughts and conversations of those five easterners after they arrived at the train depot, loaded up their crates of instruments, and made their way southwest one mile to their expedition’s base camp: the farm of a man with one of the more memorable names in Fort Worth history: Spotswood W. Lomax.

Lomax lived on Adams Street in what is today the near South Side.

Lomax lived on Adams Street in what is today the near South Side.

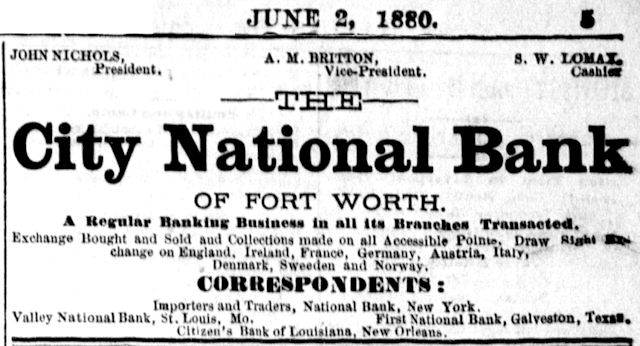

Lomax was cashier of City National Bank, one of the town’s three banks.

Lomax was cashier of City National Bank, one of the town’s three banks.

A neighbor of Lomax was Alfred M. Britton, who was vice president of City National Bank.

A neighbor of Lomax was Alfred M. Britton, who was vice president of City National Bank.

Lomax allowed the scientists to use his farm for their observations of the eclipse. Lomax and Britton also assisted the scientists. Also assisting was Minor W. McHatton, bookkeeper at City National Bank, who boarded with Britton. How, you ask, did Spotswood W. Lomax come to be hosting the five learned men from back east? All I have determined is that the scientists arrived with letters of introduction to Lomax and that St. Louis could have been the link: Two of the five scientists were from St. Louis. Lomax had been married in St. Louis in 1869, and Alfred M. Britton would be buried in St. Louis in 1911.

This photo shows Leonard Waldo, R. W. Willson, J. K. Rees, W. H. Pulsifer, F. E. Seagrave, Dallas photographer Alfred Freeman, and City National Bank vice president Alfred M. Britton with cameras and telescopes at the Lomax farm. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

This photo shows Leonard Waldo, R. W. Willson, J. K. Rees, W. H. Pulsifer, F. E. Seagrave, Dallas photographer Alfred Freeman, and City National Bank vice president Alfred M. Britton with cameras and telescopes at the Lomax farm. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

Also present at the observation site were Galveston newspaper reporter Frank Doremus and mathematics professor S. H. Lockett of East Tennessee University (he sketched the “naked-eye view of the corona” above).

The scientists spent the days before July 29 assembling and calibrating equipment and communicating by telegraph with scientists in other eclipse-observation sites around the country.

Come July 29, well before the moon began to move in front of the sun, all the scientists and volunteer assistants at the Lomax farm were in place at their telescopes, measuring instruments, and sketch pads.

The scientists were equipped with seven telescopes, cameras, polariscope, spectroscope, transit, sextant, refracting prisms, stop watches, sidereal chronometer, thermometer, and barometer.

And then, at 3:11 p.m., with all eyes on the sky, the moon approached the sun. The moon kissed the sun chastely on a fevered cheek. Emboldened, the moon—a modest orb—moved to create a more romantic setting for the couple by sliding directly in front of the sun until all that was visible of the sun was a halo around the blackened moon. Fort Worth was thrown into near darkness, giving the moon and sun a veil of privacy for two minutes and forty-two seconds.

As the scientists observed and recorded the celestial tryst, A. M. Britton sat on the roof of the Lomax house and called out every fifteen seconds “in a strong tone” the number of seconds of totality remaining. He also timed the proceedings with a stop watch.

With Britton on the roof were seven other people, most of them local residents, who had volunteered to make sketches.

(As the five learned men from back east watched this planet’s home star perform its disappearing act, were they mindful of the story of three wise men from the east who had followed a star two thousand years earlier?)

Among the experiments the five learned men conducted that day was a spectroscopic observation of the changing light from the solar chromosphere. The scientists estimated the height of the sun’s chromosphere at 524 miles. A chromosphere is a gaseous layer immediately above the photosphere of a star. The chromosphere and the corona constitute a star’s outer atmosphere. (I know, I know: And what the heck is a photosphere? One answer just spawns another question.)

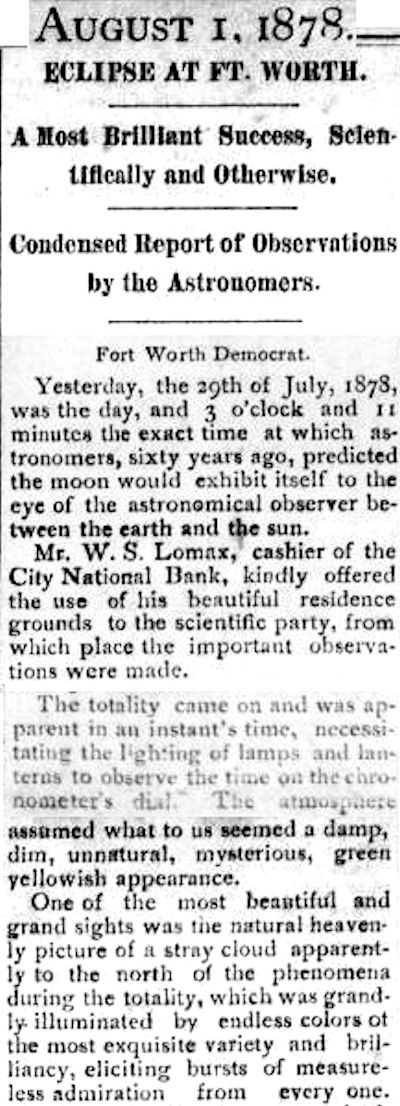

The eclipse was big news in the following days. B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat reported that the darkness during the eclipse was so great that scientists had to light lanterns to read the chronometer’s dial.

The eclipse was big news in the following days. B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat reported that the darkness during the eclipse was so great that scientists had to light lanterns to read the chronometer’s dial.

“The atmosphere assumed what to us seemed to be a damp, dim, unnatural, mysterious, green yellowish appearance. One of the most beautiful and grand sights was the natural heavenly picture of a stray cloud apparently to the north of the phenomena during the totality, which was grandly illuminated by endless colors of the most exquisite variety and brilliancy, eliciting bursts of measureless admiration from everyone.”

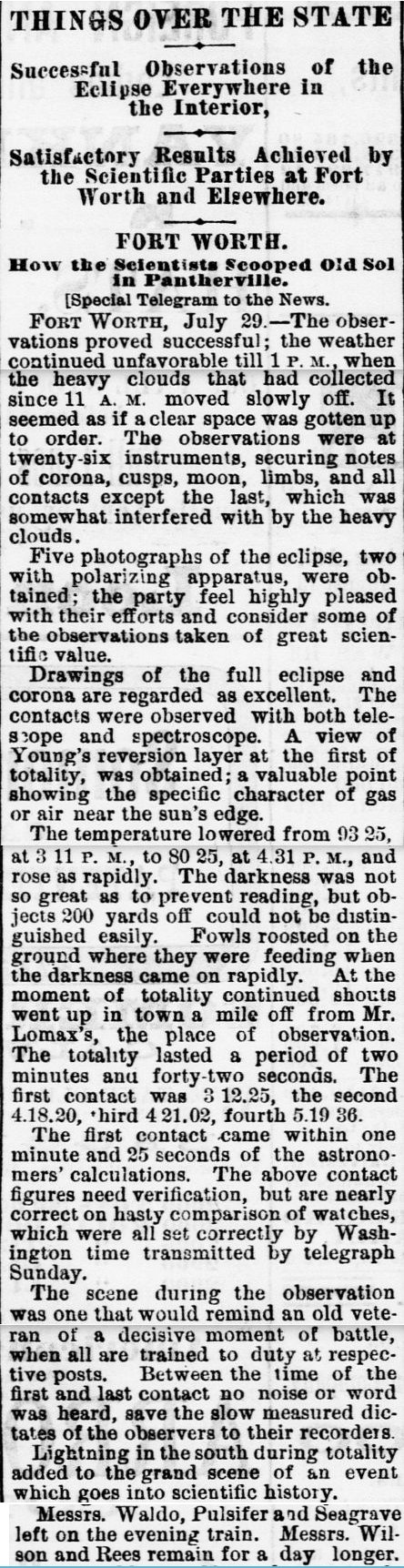

The Galveston Daily News in its report on “Old Sol in ‘Pantherville’” wrote: “The darkness was not so great as to prevent reading, but objects 200 yards off could not be distinguished easily. Fowls roosted on the ground where they were feeding when the darkness came on rapidly. At the moment of totality continued shouts went up in town a mile off from Mr. Lomax’s.” The eclipse caused the temperature to drop from 93 to 80 degrees.

The Galveston Daily News in its report on “Old Sol in ‘Pantherville’” wrote: “The darkness was not so great as to prevent reading, but objects 200 yards off could not be distinguished easily. Fowls roosted on the ground where they were feeding when the darkness came on rapidly. At the moment of totality continued shouts went up in town a mile off from Mr. Lomax’s.” The eclipse caused the temperature to drop from 93 to 80 degrees.

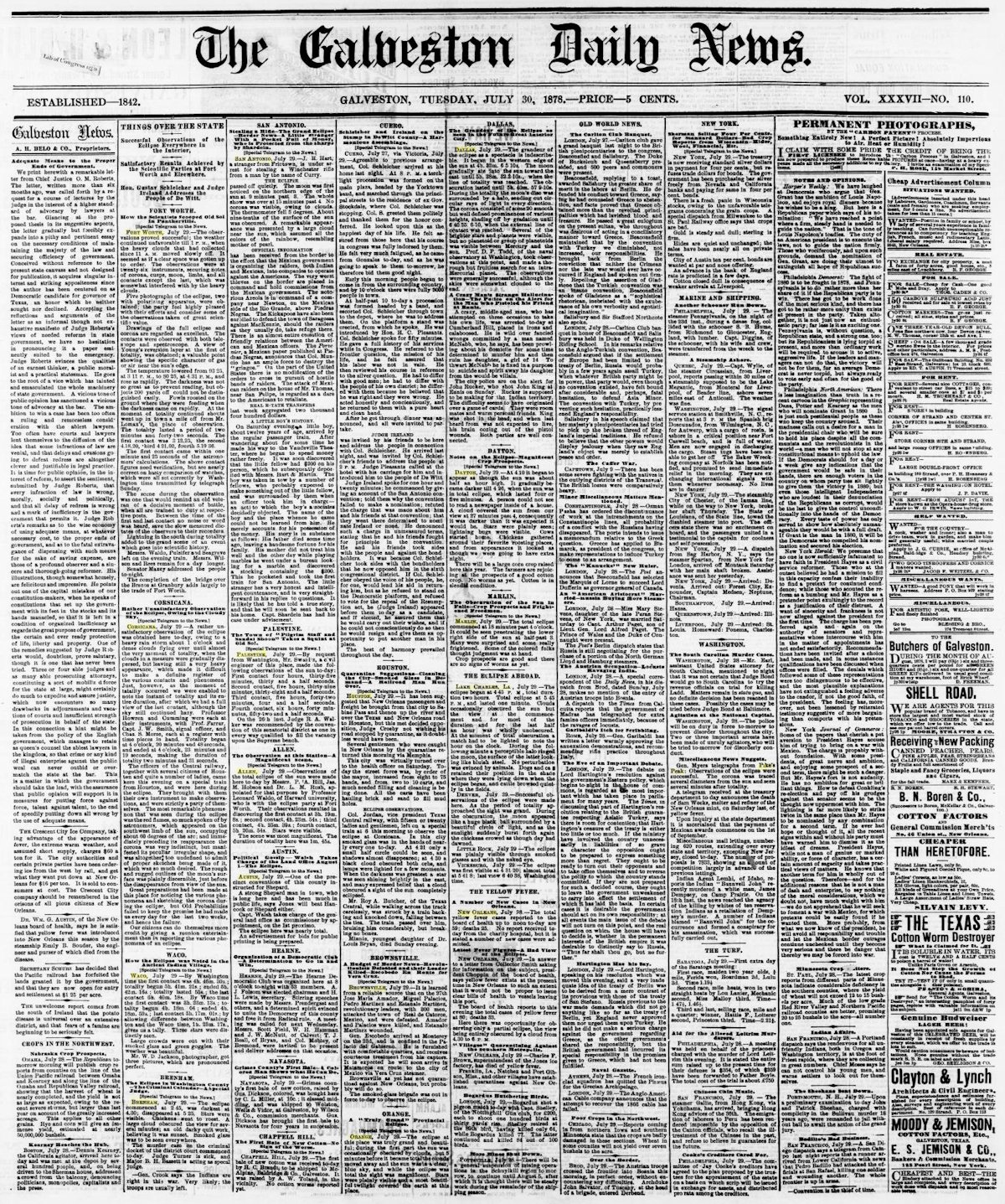

On the front page of the Galveston newspaper, other cities in Texas and Louisiana reported their view of the eclipse.

On the front page of the Galveston newspaper, other cities in Texas and Louisiana reported their view of the eclipse.

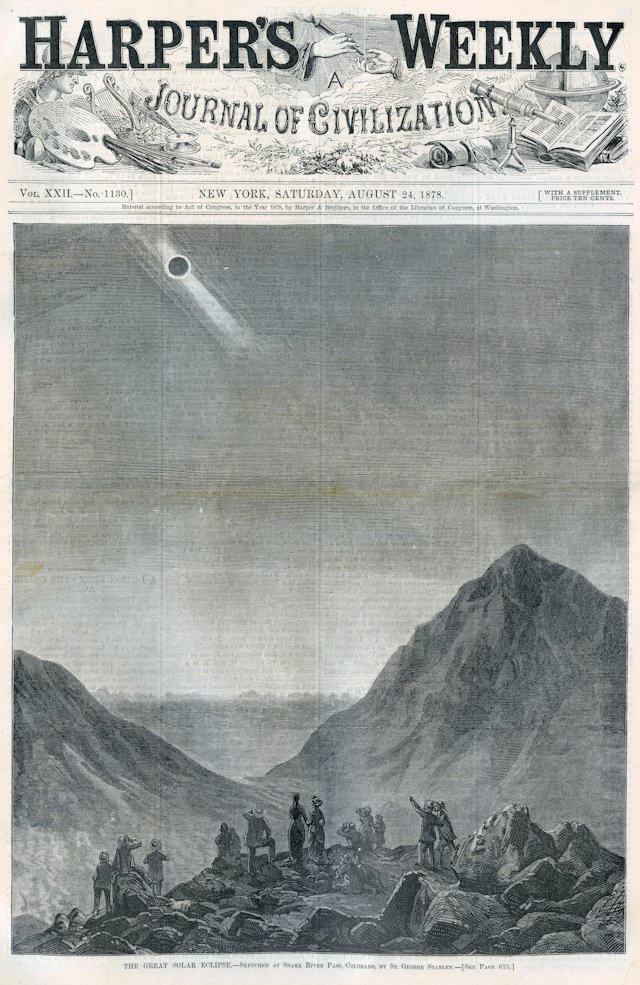

Even nationally the eclipse promoted the sun and moon—briefly—to the status of a power couple. This cover of Harper’s Weekly of August 24 depicts eclipse observers at Snake River Pass, Colorado.

Even nationally the eclipse promoted the sun and moon—briefly—to the status of a power couple. This cover of Harper’s Weekly of August 24 depicts eclipse observers at Snake River Pass, Colorado.

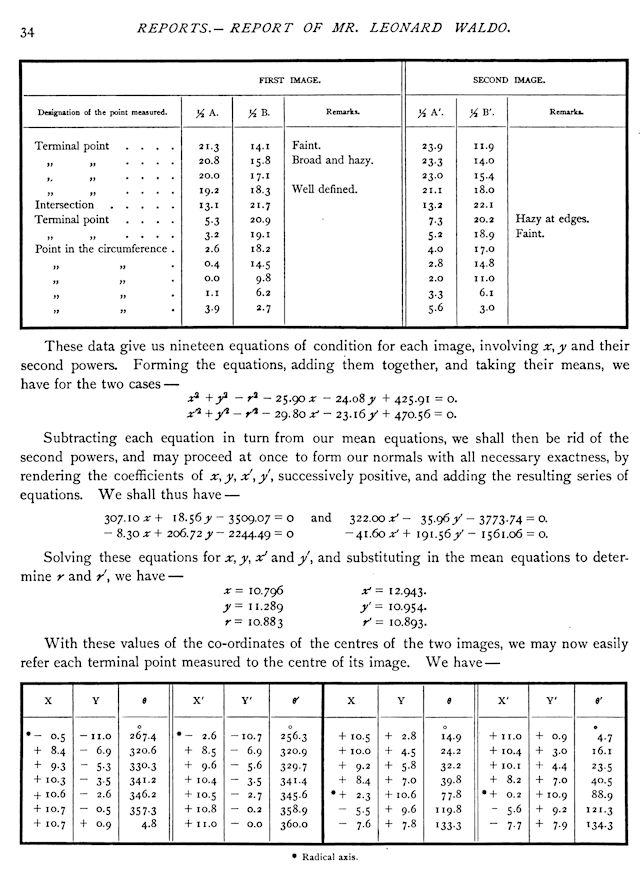

Not surprisingly, Leonard Waldo and colleagues were very detailed in their observation of the solar eclipse. How detailed? In 1879 Waldo published a ninety-two-page book about the scientists’ observations of an event that lasted two minutes and forty-two seconds.

The book was written for other scientists, and predictably most of the book is equations and charts and dense jargon far beyond the ken of most mortals.

The book was written for other scientists, and predictably most of the book is equations and charts and dense jargon far beyond the ken of most mortals.

The observations of these five learned men from back east were the first scientific study of the sun conducted in Texas and among the first studies of a solar eclipse conducted in the United States.

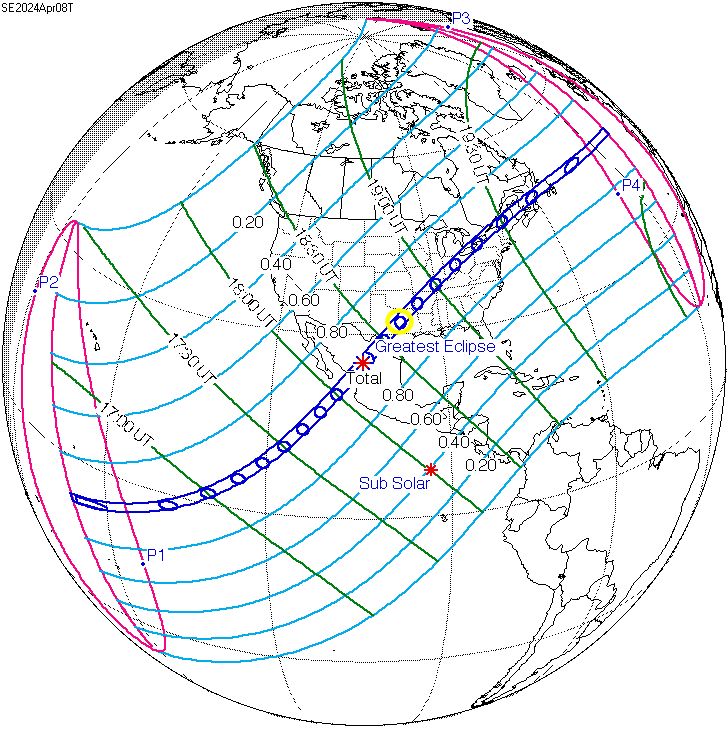

Mark your calendar: On April 8, 2024 you’ll get a chance to see what the five learned men from back east and Cowtowners of 1878 saw: Fort Worth will again be smack dab in the path of a total solar eclipse. Downtown will get two and a half minutes of totality. (Image from Wikipedia.)

Mark your calendar: On April 8, 2024 you’ll get a chance to see what the five learned men from back east and Cowtowners of 1878 saw: Fort Worth will again be smack dab in the path of a total solar eclipse. Downtown will get two and a half minutes of totality. (Image from Wikipedia.)

Read more about Texas solar eclipses.

(Thanks and a tip of the telescope to Dennis Hogan for the heads-up.)

Just consider that we can have this view of eclipse totality again in 2024!

Thanks again for the tip, Dennis.