The flood of 1908 was the second of Fort Worth’s great floods. And just like the floods of 1889, 1922, and 1949, the flood of oh-eight showed what a difference a day makes.

On Thursday, April 16, 1908, even though rain had fallen in Fort Worth for eleven days in a row, this was the only weather story on page 1 of the Telegram. The forecast was for “fair” weather.

On Thursday, April 16, 1908, even though rain had fallen in Fort Worth for eleven days in a row, this was the only weather story on page 1 of the Telegram. The forecast was for “fair” weather.

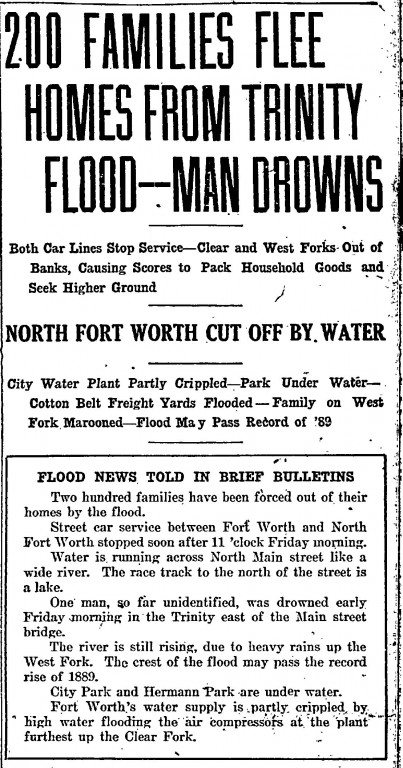

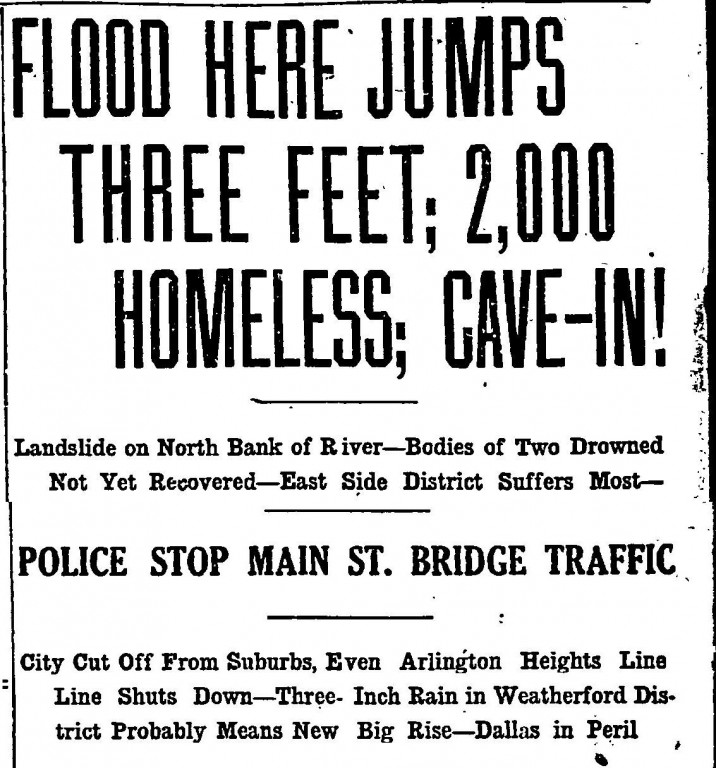

These were the page 1 headlines the next day.

These were the page 1 headlines the next day.

Heavy rain began to fall early on Friday, April 17. Suddenly in the first seventeen days of April Fort Worth had received twice its normal rainfall for the entire month. Overnight the Telegram had gone from publishing an unalarming forecast to wondering if the water level of the great flood of 1889 would be surpassed.

Downltown was cut off from the communities across the river to the west, north, and east. Streetcars couldn’t operate. The city water supply plant was “partly crippled.” One person was dead. Fort Worth’s population in 1908 was estimated at sixty-eight thousand.

(In the clip, City Park is Trinity Park today. Hermann Park was at North Main and Northwest 2nd streets.)

This postcard shows the flood water over North Main Street at Northwest 2nd Street. Hermann Park was under water, as was the race track to the north. (Postcard from Barbara Love Logan.)

This postcard shows the flood water over North Main Street at Northwest 2nd Street. Hermann Park was under water, as was the race track to the north. (Postcard from Barbara Love Logan.)

On April 18 the rain continued to fall, and the river continued to rise. The newspaper reported two more people dead. As the river rose mudslides occurred, houses floated away, telephone and telegraph lines went down, streetlights went out, livestock drowned, bridges washed away. Fort Worth couldn’t even bury its dead: Funerals were postponed because Oakwood Cemetery was unreachable.

On April 18 the rain continued to fall, and the river continued to rise. The newspaper reported two more people dead. As the river rose mudslides occurred, houses floated away, telephone and telegraph lines went down, streetlights went out, livestock drowned, bridges washed away. Fort Worth couldn’t even bury its dead: Funerals were postponed because Oakwood Cemetery was unreachable.

At night police patrolled the river bottom and fired pistols to warn residents living in the lowlands to move to higher ground. By Saturday, April 18, even Henry Silas Ferrell, a woodcutter who lived on the bank of the river near Main Street, had met his match. The flood of 1908 forced him to do what even the great flood of 1889 had not done: He skedaddled to higher ground.

At night police patrolled the river bottom and fired pistols to warn residents living in the lowlands to move to higher ground. By Saturday, April 18, even Henry Silas Ferrell, a woodcutter who lived on the bank of the river near Main Street, had met his match. The flood of 1908 forced him to do what even the great flood of 1889 had not done: He skedaddled to higher ground.

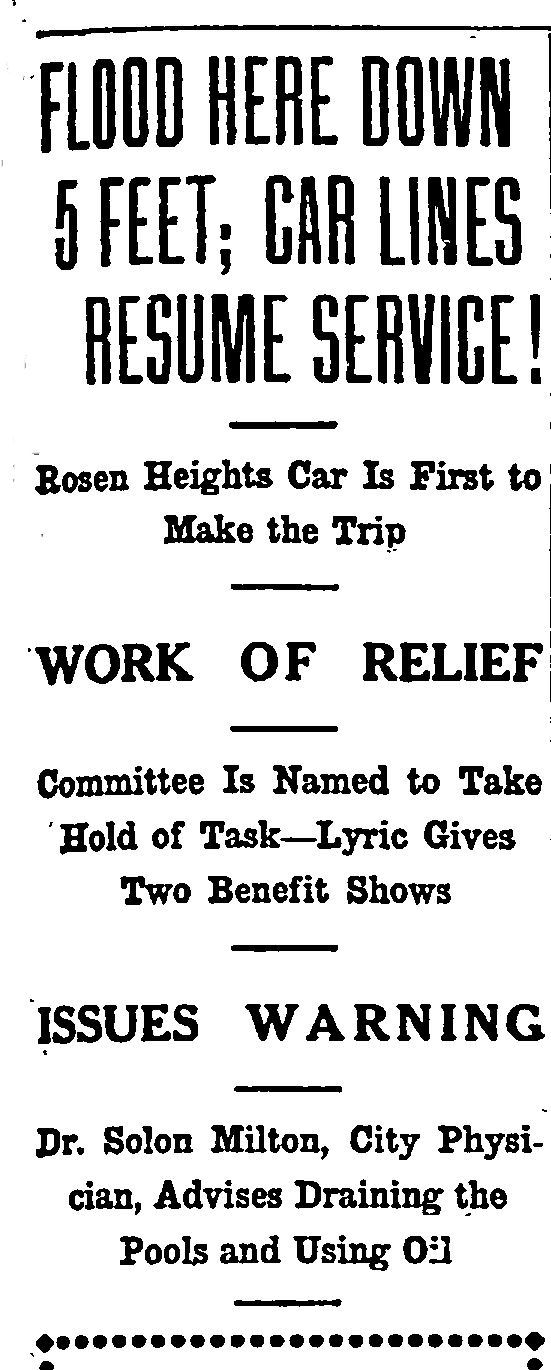

On Sunday, April 19, the Telegram began to call for donations to help flood victims. Fire and Police Commissioner George Mulkey toured the flooded areas and declared 2,500 people homeless.

On Sunday, April 19, the Telegram began to call for donations to help flood victims. Fire and Police Commissioner George Mulkey toured the flooded areas and declared 2,500 people homeless.

That Sunday was Easter. Two churches and the phone company managed to transmit Easter services over telephone lines to people who were unable to go to church because of high water.

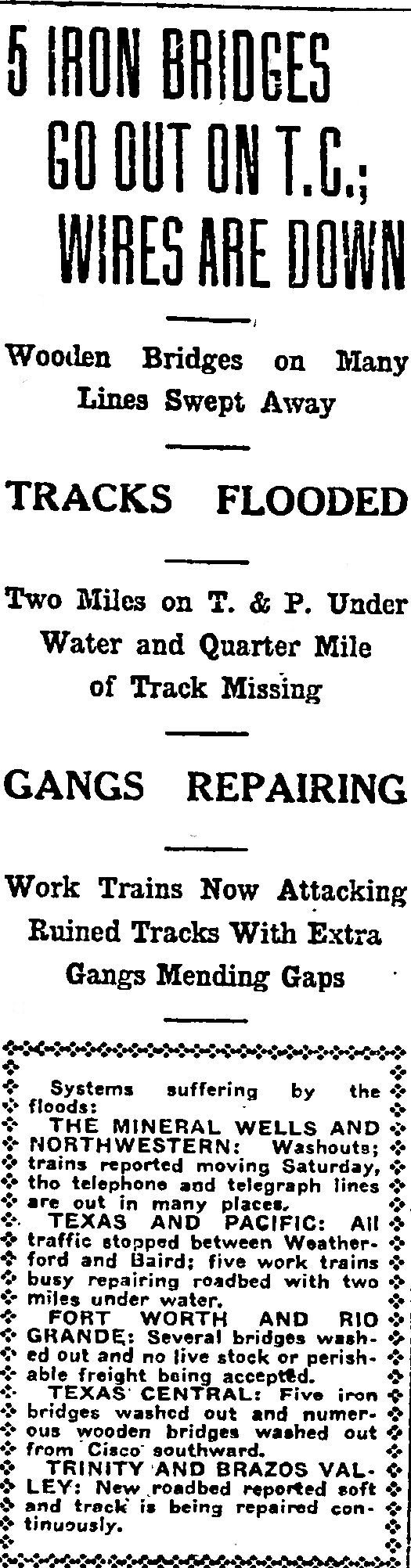

The flood wreaked havoc on the railroads. Trainmen of the Rock Island railroad said the Trinity was seven miles wide at Newark (that part of the river would not become Eagle Mountain Lake until 1932).

The flood wreaked havoc on the railroads. Trainmen of the Rock Island railroad said the Trinity was seven miles wide at Newark (that part of the river would not become Eagle Mountain Lake until 1932).

By April 20, the day after Easter, the tide was turning—literally: The water level began to fall. Some public services were restored; relief efforts continued; the Lyric vaudeville theater on Houston Street gave benefit shows. The city physician urged that standing water be drained or treated with oil to prevent mosquitoes from breeding.

By April 20, the day after Easter, the tide was turning—literally: The water level began to fall. Some public services were restored; relief efforts continued; the Lyric vaudeville theater on Houston Street gave benefit shows. The city physician urged that standing water be drained or treated with oil to prevent mosquitoes from breeding.

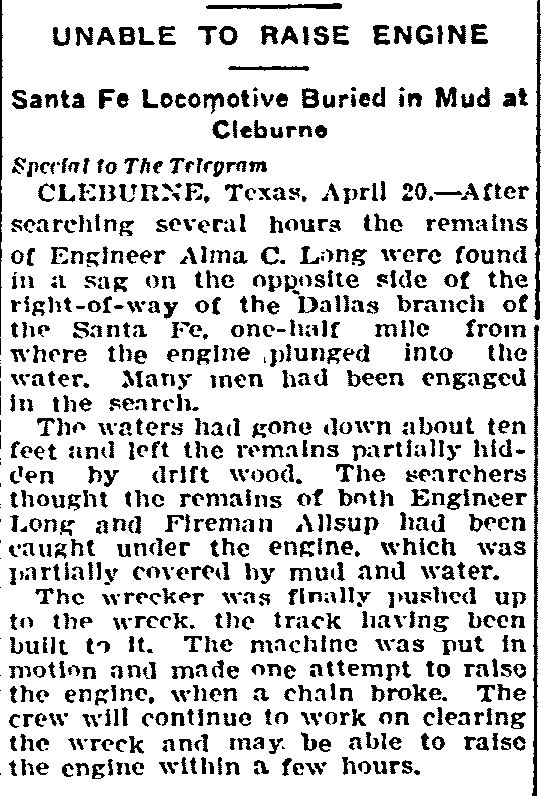

As the water level fell, searchers found the body of an engineer who had been missing since his locomotive had been swept off the track by flood water and partially submerged in mud.

As the water level fell, searchers found the body of an engineer who had been missing since his locomotive had been swept off the track by flood water and partially submerged in mud.

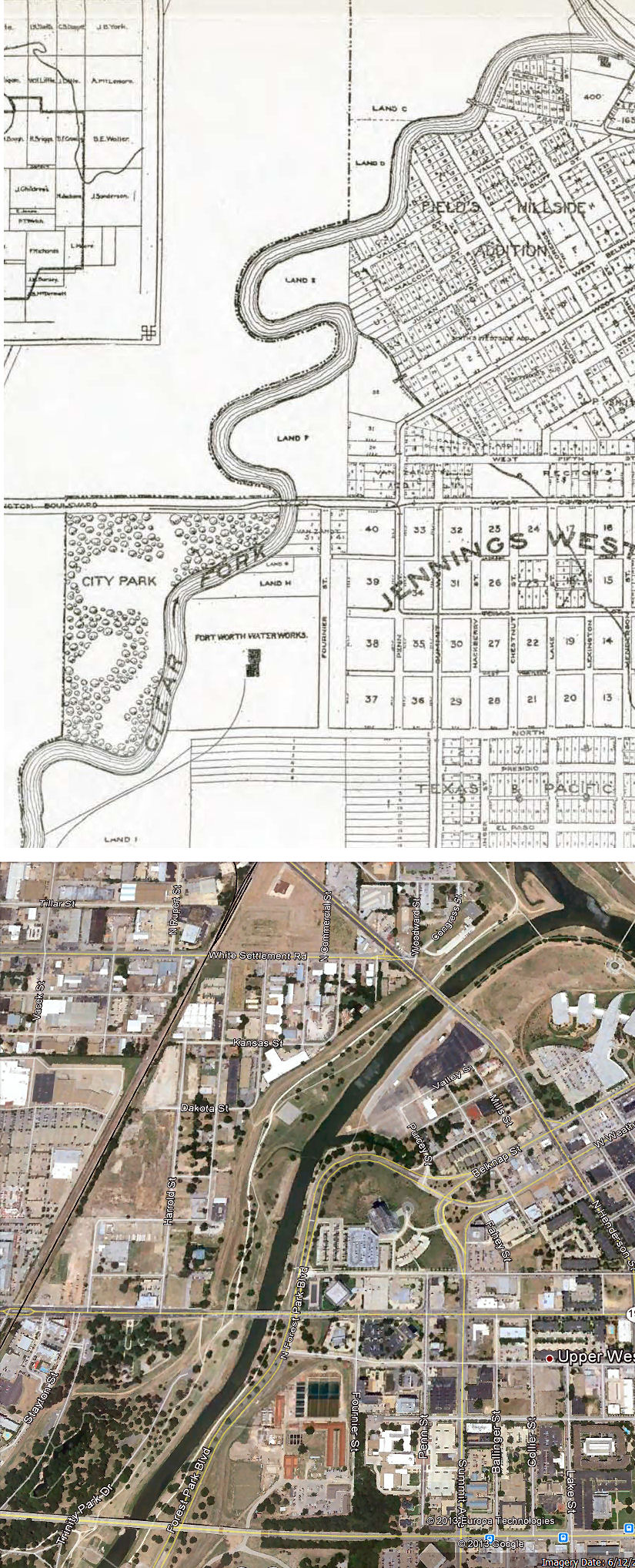

Today when we look at the wide, laidback Trinity it’s hard to imagine such a rampage. But the river of 2015 is not the river of 1908. In 1908 the river channel was narrower and more convoluted than it is today. It was not contained by the high levees of today. That skinny, squirmy channel of 1908 could not drain a sudden and heavy rainfall from its watershed. Compare these images, from 1907 and 2013, of the Clear Fork from Lancaster northeast to the confluence with the West Fork. (On the 1907 map North Street became Lancaster.) (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

Today when we look at the wide, laidback Trinity it’s hard to imagine such a rampage. But the river of 2015 is not the river of 1908. In 1908 the river channel was narrower and more convoluted than it is today. It was not contained by the high levees of today. That skinny, squirmy channel of 1908 could not drain a sudden and heavy rainfall from its watershed. Compare these images, from 1907 and 2013, of the Clear Fork from Lancaster northeast to the confluence with the West Fork. (On the 1907 map North Street became Lancaster.) (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

The flood of 1908 did not surpass the record water level of the great flood of 1889, although it came close: At the old waterworks plant a nail on a wall marked the highest level of the water during the 1889 flood. At 1 p.m. on April 20, 1908, the river crested just nineteen inches below that nail.

Fourteen years later, on April 25, 1922, the river would make another run at that nail.

Posts about weather:

“Greatest Tragedy of the Century” (Part 1): “Dead Outnumbers the Living”

Winter 1930: Lake Worth Ice Capades

The Deep Freeze of Fifty-One

Texas Toast: The Summers of 1980 and 2011

The Flood of 1889: The First of the Big Four

Double Trouble: The Twofer Flood of 1915

From Beneficial to Torrential: The Flood of Twenty-Two

The Flood of Forty-Nine: People in Trees, Horses on Roofs

Deja Deluge: Forty Years On, the Flood of 1989