During the month of April 1897 (see Part 1, Part 2) the skies of Texas were seemingly bumper to bumper with mysterious airships: large cigar-shaped craft outfitted with wings and searchlights and motors. Did Fort Worth get its share of traffic?

Yes, indeed. Residents of Fort Worth saw airships. One resident even claimed to have boarded an airship. And another man claimed to have boarded an airship that was invented and owned by a former resident of Fort Worth.

For starters, Walter M. Hanney, a conductor on the Houston & Texas Central railroad, saw an airship as he sat on his porch on the night of April 16. This clip is from the April 17 Dallas Morning News.

For starters, Walter M. Hanney, a conductor on the Houston & Texas Central railroad, saw an airship as he sat on his porch on the night of April 16. This clip is from the April 17 Dallas Morning News.

On April 18 the Morning News reported that Jack Farley of Denison was in Fort Worth on the night of April 16 “and swears by all that is good and holy that he saw the airship sailing over the town.”

On April 20 the Dallas Times Herald wrote: “Fort Worth, April 19—At last the aerial wonder causing so much comment all over the country has been seen in Fort Worth; at least there are some good citizens who declare they witnessed its appearance last night. L. E. James says he saw it land in the city park [Trinity Park] last night, when a man at least seven feet tall alighted from it and appeared to be fastening some ropes after which he boarded it again when it swiftly arose and soon disappeared from view. J. E. Johnson at the Natatorium says he saw it plainly last night passing over the city.”

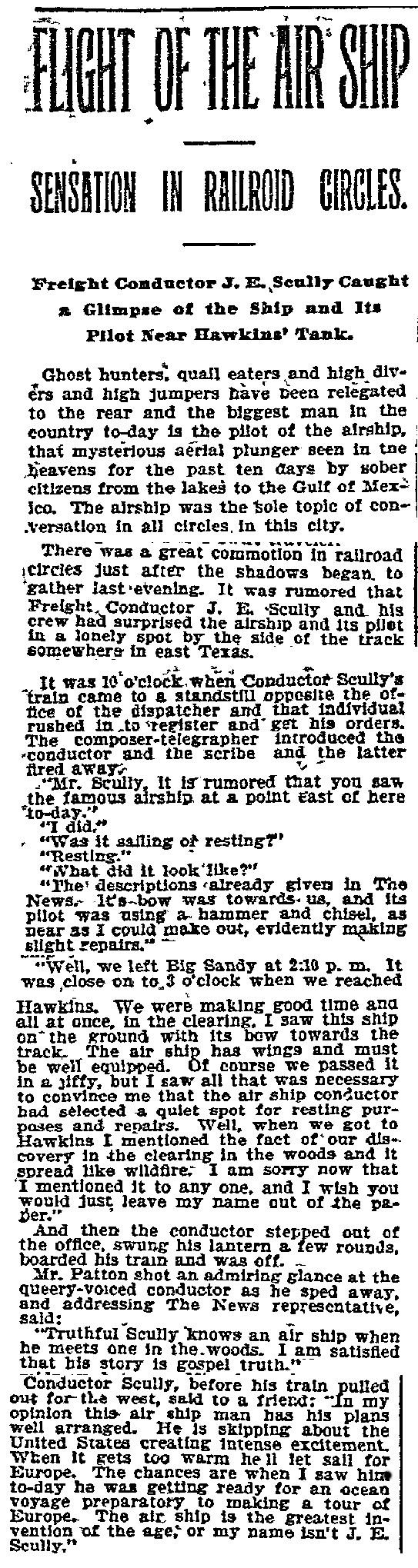

And another Fort Worth man, also a railroad conductor, had his fifteen minutes of fame after claiming he saw an airship, also on April 16. Joseph E. Scully worked for the Texas & Pacific railroad and had a reputation for honesty. He claimed that he saw an airship on the ground in Wood County in east Texas as his train passed. This clip is from the April 17 Morning News.

And another Fort Worth man, also a railroad conductor, had his fifteen minutes of fame after claiming he saw an airship, also on April 16. Joseph E. Scully worked for the Texas & Pacific railroad and had a reputation for honesty. He claimed that he saw an airship on the ground in Wood County in east Texas as his train passed. This clip is from the April 17 Morning News.

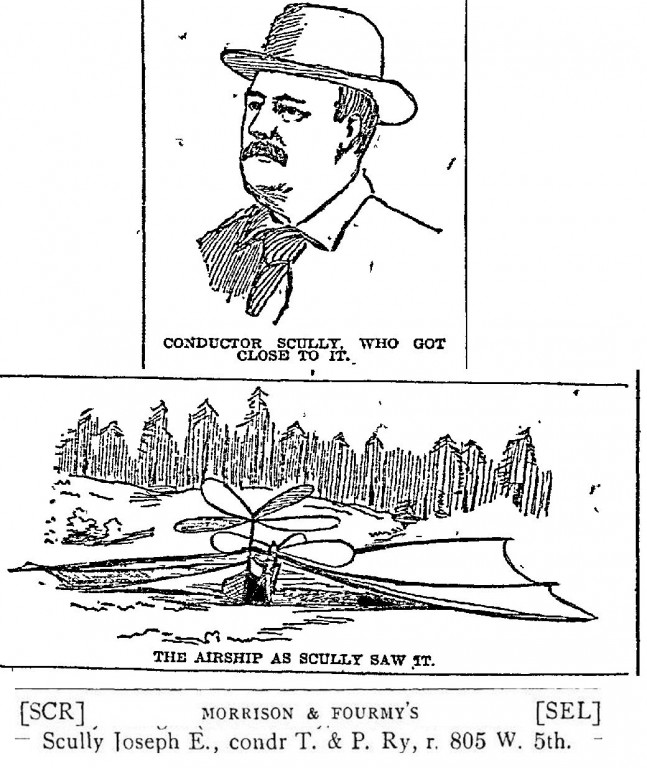

These two illustrations accompanied the published interview with Scully.

These two illustrations accompanied the published interview with Scully.

On April 18 the Morning News quoted people who attested to Scully’s honesty. John L. Ward said the airship sighting was a good omen, foretelling a win for the Fort Worth Panthers baseball team. John Ward and his brother Bill owned the White Elephant Saloon. Note in the bottom clip that the next day, after the Panthers lost the game, Bill Ward told the Morning News that the Fort Worth players couldn’t concentrate on the game because they were watching the sky for that “consarned airship.”

On April 18 the Morning News quoted people who attested to Scully’s honesty. John L. Ward said the airship sighting was a good omen, foretelling a win for the Fort Worth Panthers baseball team. John Ward and his brother Bill owned the White Elephant Saloon. Note in the bottom clip that the next day, after the Panthers lost the game, Bill Ward told the Morning News that the Fort Worth players couldn’t concentrate on the game because they were watching the sky for that “consarned airship.”

And what about coverage of the airship phenomenon by Fort Worth journalists? Oddly, during the first half of April, the Fort Worth Register had not given a drop of ink to airship stories. The Morning News was scooping it every day. That changed on April 18. The Register came out with a doozy. The Register reported that Patrick C. Byrnes of Fort Worth, a Texas & Pacific worker, not only saw an airship but also was allowed to enter it, explore it, question the crew. Byrnes said the airship—cigar-shaped, about two hundred feet long—was carrying “several tons of dynamite” that would be dropped on Spanish soldiers and ships in Cuba.

And what about coverage of the airship phenomenon by Fort Worth journalists? Oddly, during the first half of April, the Fort Worth Register had not given a drop of ink to airship stories. The Morning News was scooping it every day. That changed on April 18. The Register came out with a doozy. The Register reported that Patrick C. Byrnes of Fort Worth, a Texas & Pacific worker, not only saw an airship but also was allowed to enter it, explore it, question the crew. Byrnes said the airship—cigar-shaped, about two hundred feet long—was carrying “several tons of dynamite” that would be dropped on Spanish soldiers and ships in Cuba.

And yet, two days after printing that jaw-dropping story, the Register followed up in its column on railroads with this profoundly ho-hum entry about Byrnes’s experience.

And yet, two days after printing that jaw-dropping story, the Register followed up in its column on railroads with this profoundly ho-hum entry about Byrnes’s experience.

On April 23 the Register reported that a perfectly sober W. T. Gray of Fort Worth had seen an airship while fishing at Harmon’s Lake north of town.

On April 23 the Register reported that a perfectly sober W. T. Gray of Fort Worth had seen an airship while fishing at Harmon’s Lake north of town.

And on April 24 the Register was back with another topper. Woodford Brooks, an official of the Poly streetcar company, had encountered an airship in Trinity Park and had chatted with the pilot, Captain Randall. Randall told Brooks that the airship, with thirteen aboard, was bound for Mexico City and had landed to get a fill-up of electricity after mistaking the Fort Worth waterworks for an electric power plant. Brooks later told the Register that Captain Randall had sent him a telegram from San Antonio.

And on April 24 the Register was back with another topper. Woodford Brooks, an official of the Poly streetcar company, had encountered an airship in Trinity Park and had chatted with the pilot, Captain Randall. Randall told Brooks that the airship, with thirteen aboard, was bound for Mexico City and had landed to get a fill-up of electricity after mistaking the Fort Worth waterworks for an electric power plant. Brooks later told the Register that Captain Randall had sent him a telegram from San Antonio.

By May newspapers in Texas and elsewhere in the Midwest had largely replaced news of airship sightings with news of more mundane matters. But on May 12 the Fort Worth Register got in one last “wow” story. None other than civic leader Major James Jones Jarvis was reported to have seen an airship land three miles north of town near his property. Furthermore, guests of the captain of the airship were said to have included the assistant secretary of war and his wife.

By May newspapers in Texas and elsewhere in the Midwest had largely replaced news of airship sightings with news of more mundane matters. But on May 12 the Fort Worth Register got in one last “wow” story. None other than civic leader Major James Jones Jarvis was reported to have seen an airship land three miles north of town near his property. Furthermore, guests of the captain of the airship were said to have included the assistant secretary of war and his wife.

Take that, Morning News!

So. Back in April of 1897, what did folks make of all these airship sightings? Theories included hoaxes being perpetrated, eyewitnesses being drunk, inventors testing their flying machines, the government testing secret weapons, space aliens visiting, and Spaniards spying.

And what do we make of it all 125 years later? The great airship phenomenon of April 1897 continues to fascinate people. At least four books have been written about it.

After you read dozens of newspaper reports of sightings, some aspects of the reports stand out:

• Sightings were numerous in both time and space. As airships were being reported seen in several places on the same day in Texas, airships were being reported seen on that same day in Indiana and Illinois and Michigan.

• Eyewitness descriptions of the airships were similar: Sightings usually occurred at night—cigar-shaped craft with motors, wings, and a bright headlight. The occupants were (usually) human. Such similarity in descriptions could mean that people were seeing the same airship or similar airships or that people were merely repeating a description that they had heard or read.

• Spain was an element in a few reports. People may have consciously or unconsciously had the threat of war on their mind.

• I found no reports of anyone being harmed in airship encounters. In some cases horses were frightened, but most people did not report being even especially frightened by their encounter.

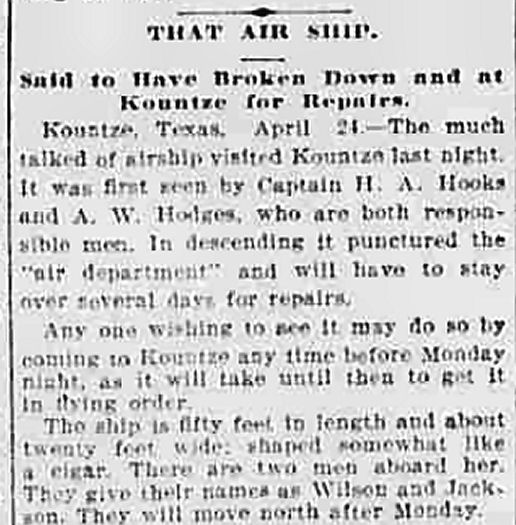

• Finally, here is another recurring feature. At least five witnesses who claimed to have actually talked with an occupant of an airship reported that the occupant gave his name as “Wilson.” On April 25 the Houston Daily Post reported on an airship sighting at Kountze. One of the two men on board gave his name as “Wilson.”

• Finally, here is another recurring feature. At least five witnesses who claimed to have actually talked with an occupant of an airship reported that the occupant gave his name as “Wilson.” On April 25 the Houston Daily Post reported on an airship sighting at Kountze. One of the two men on board gave his name as “Wilson.”

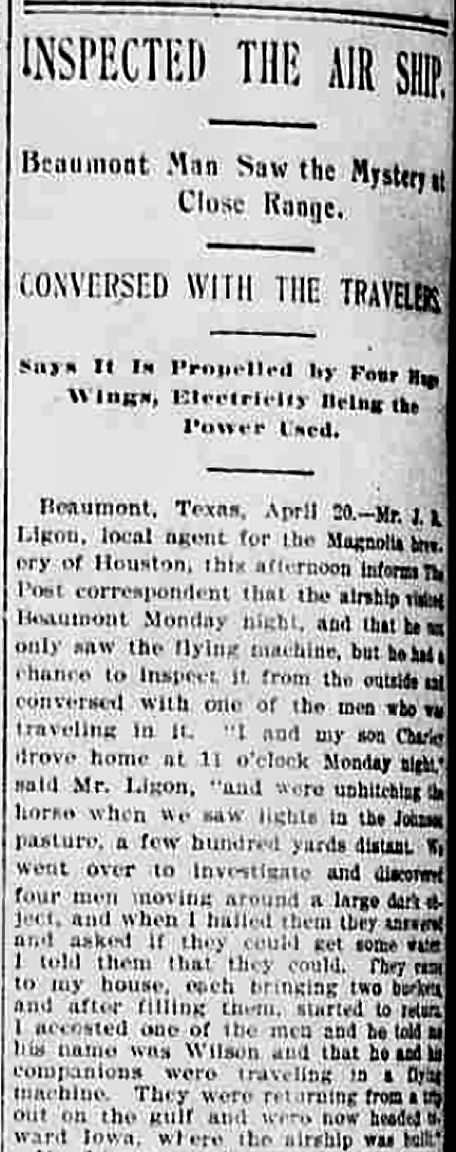

On April 21, 1897 the Houston Daily Post reported an airship sighting at Beaumont. The witness said he talked with an airship occupant who gave his name as “Wilson.”

On April 21, 1897 the Houston Daily Post reported an airship sighting at Beaumont. The witness said he talked with an airship occupant who gave his name as “Wilson.”

On April 26, in a story headlined “The Airship in San Antonio,” the San Antonio Express wrote about the occupants of an airship seen there: “The investors [inventors?] were Hiram Wilson, a native of New York and son of Willard H. Wilson, assistant master mechanic of the New York Central Railroad, and a young electrical engineer, C. J. Walsh of San Francisco.”

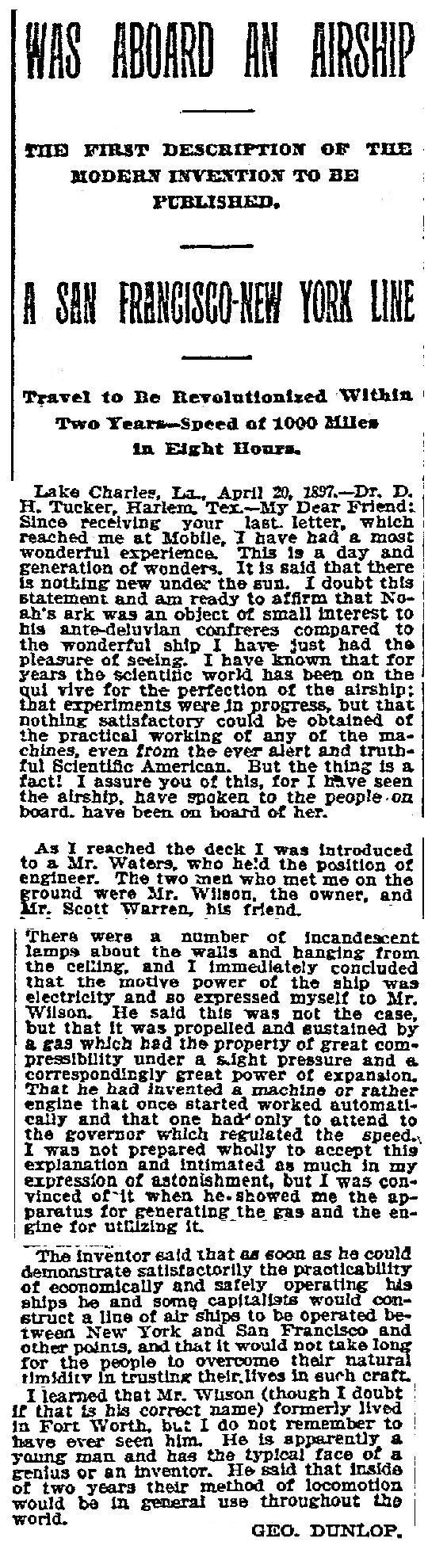

And two of the five witnesses who said an airship occupant identified himself as “Wilson” said Wilson told them that he had lived in Fort Worth. On May 16 the Dallas Morning News printed a letter written on April 20 by George Dunlop. In his detailed letter Dunlop claimed to have seen an airship in flight. The airship stopped overhead, two men descended on a ladder, greeted Dunlop, and invited him to climb aboard. This Dunlop did. One of the two occupants of the airship—the inventor and owner of the airship—was a Mr. Wilson, who “formerly lived in Fort Worth.” Wilson told Dunlop that the “motive power” of the airship was a compressed gas and that he had invented an engine that used that gas. Wilson said he had been flying one of his three airships in Texas and that he hoped to operate them in passenger service between San Francisco and New York.

And two of the five witnesses who said an airship occupant identified himself as “Wilson” said Wilson told them that he had lived in Fort Worth. On May 16 the Dallas Morning News printed a letter written on April 20 by George Dunlop. In his detailed letter Dunlop claimed to have seen an airship in flight. The airship stopped overhead, two men descended on a ladder, greeted Dunlop, and invited him to climb aboard. This Dunlop did. One of the two occupants of the airship—the inventor and owner of the airship—was a Mr. Wilson, who “formerly lived in Fort Worth.” Wilson told Dunlop that the “motive power” of the airship was a compressed gas and that he had invented an engine that used that gas. Wilson said he had been flying one of his three airships in Texas and that he hoped to operate them in passenger service between San Francisco and New York.

And on April 24, in a story headlined “The Airship in West Texas / Landed in the Town of Uvalde,” the Galveston Daily News wrote: “Sheriff H. W. Baylor . . . went out to investigate and was surprised to find there the airship and crew of three men . . . One of the men, who gave his name as Wilson and place of residence as Goshen, New York, inquired for Captain C. C. Akers, former sheriff of Zavala County, who he understood lived in this section. He said he had met Captain Akers in Fort Worth in 1877 and liked him very much.”

Indeed, on April 28 the Galveston Daily News printed a letter to the editor from Akers:

“Noting that on the airship said to have been seen by Sheriff Baylor in Uvalde was a man who gave his name as Wilson, I can say that while living in Fort Worth in ’76 and ’77 I was well acquainted with a man by the name of Wilson from New York state and was on very friendly terms with him. He was of a mechanical turn of mind and was working on aerial navigation and something that would astonish the world.”

So, what is the explanation? Beats me. You won’t find any answers here. Personally, I suspect a combination of factors: hoax, power of suggestion (maybe even mass hysteria), maybe even a real airship or two. None of the reports of airship sightings mentions hot air, helium, hydrogen, or any other means of buoyancy. Were these airships heavier than air or lighter than air? These sightings occurred before the Wright brothers flew their heavier-than-air plane, before Count Zeppelin flew his lighter-than-air rigid airship, but inventors of the time had at least envisioned craft that resembled the airships reported seen in April of 1897. Lighter-than-air craft certainly existed in 1897. Balloons had been used for reconnaissance during the Civil War. Aerialists had been making balloon ascensions at fairs in the United States for at least a decade.

Some attempts to explain April of 1897 accept at least some of the airship reports as genuine. Michael Busby’s book Solving the 1897 Airship Mystery theorizes that the airships (plural) were built by a handful of inventors (including former Fort Worth resident Hiram Wilson) working in secret and were flown until the craft were destroyed in accidents.

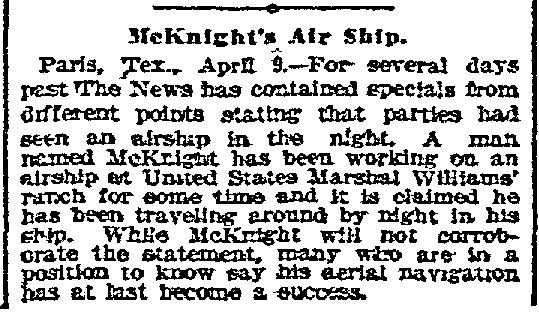

On April 10, 1897 the Morning News printed a report from Paris, Texas, that mentioned U.S. Marshal Williams. Author Busby thought an airship was hidden during daylight hours at the ranch belonging to U.S. Marshal John Shelby Williams of the eastern district of Texas.

On April 10, 1897 the Morning News printed a report from Paris, Texas, that mentioned U.S. Marshal Williams. Author Busby thought an airship was hidden during daylight hours at the ranch belonging to U.S. Marshal John Shelby Williams of the eastern district of Texas.

And remember the men S. E. Tilman and A. E. Dolbear who were said to be the airship occupants in C. L. McIlhany’s eyewitness report from Stephenville in Part 2? Busby claimed that these two men were professors Samuel E. Tillman and Amos E. Dolbear, who had expertise in electricity and chemistry. And Busby thought the “capitalists of New York” mentioned by McIlhany included William Randolph Hearst.

But, of course, the most common explanation given for April of 1897 is big, fat hoax. But who was big fat hoaxing whom? Today, with little to go on but newspaper accounts, which ranged from wild-eyed to blasé, it’s hard to tell. (The theory that the hoax began as an April Fools’ joke and was perpetuated through the month is countered by the fact that there were some airship reports in March.)

Some of the published reports of sightings were submitted to newspapers by alleged eyewitnesses. The newspapers apparently published such reports without editing and with no questions asked, no facts checked, no corroboration made. Today that would be considered inexcusable journalism. Perhaps journalists chose not to ask questions, preferring to print stories that sold papers. Perhaps newspapers printed such stories with a wink-wink to their readers, trusting readers to know when their collective leg was being pulled by the submitter.

Perhaps even journalists themselves made up such sightings. But the reports often cited real people—some of them people of high civic standing. If newspapers made up this stuff and quoted real people as eyewitnesses, why didn’t those witnesses demand a retraction? I find no retractions, no charges or admissions of hoax or error or misquotation.

And, if mischievous journalists made up accounts of sightings or knowingly accepted a false report from an “eyewitness,” those journalists risked their jobs by risking the credibility of their employers—newspapers.

Whether fact or fiction, as the reported sightings grew in number, the power of suggestion must have become a contributor. After people read in newspapers that mysterious airships were “out there,” such craft became easier for expectant people to “see.” Thus, at night people might mistake celestial bodies for airships. In at least one case the searchlight of an airship was later found to have been the headlight of a locomotive.

The rash of airship sightings began in California in autumn of 1896 and by spring of 1897 had spread to the Midwest, including Texas. Years later, one explanation goes, a retired railroad telegrapher admitted that the hoax in the Midwest had been started by railroad telegraph operators in Iowa who made up an airship sighting story and sent it out on the telegraph wire, where it was read and repeated by other railroad telegraph operators. Then newspapers picked up the story. In Texas, this explanation goes, Fort Worth’s T&P conductor Joseph E. “Truthful” Scully, mentioned earlier, had been selected to spread the hoax because of his reputation for veracity.

Indeed, the most recurring profession of eyewitnesses in dozens of airship sighting reports was that of railroad worker, such as Scully, Byrnes, Hanney, and Dunlap (see below).

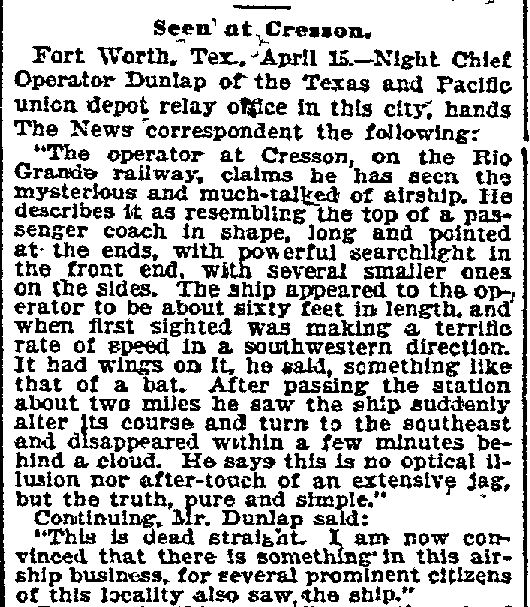

This report in the Dallas Morning News of April 16 illustrates how the hoax might operate: A railroad telegraph operator in Cresson told a railroad telegraph operator in Fort Worth that he had seen an airship. The Fort Worth operator winked and passed this report to the newspaper, which printed what it had been told.

This report in the Dallas Morning News of April 16 illustrates how the hoax might operate: A railroad telegraph operator in Cresson told a railroad telegraph operator in Fort Worth that he had seen an airship. The Fort Worth operator winked and passed this report to the newspaper, which printed what it had been told.

But again the argument can be made that by perpetrating a giant hoax, railroad workers risked their jobs by risking the credibility of their employer.

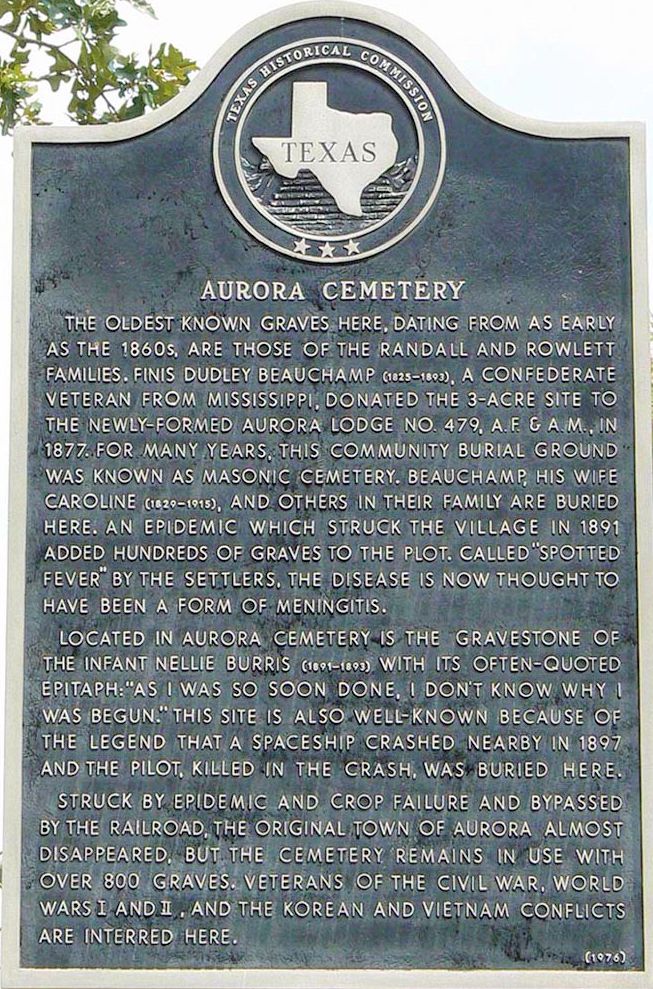

And what about Aurora (see Part 1), the best-known airship sighting of that April of 1897? Barbara Brammer, Aurora historian and a former Aurora mayor, did some research and concluded that Aurora resident S. E. Haydon, who submitted that lone report published in the Dallas Morning News, made up the Aurora Martian airship crash to help revive the economy of Aurora, which had been bypassed by the railroad and had lost much of its population. He may have read the newspaper reports of sightings of airships occupied by humans and decided to go them one better and put a Martian at the helm of his.

Today in Aurora no evidence of the crash remains. The well into which the crash debris supposedly was dumped has been filled with cement and a building built over it. In 1973 the Mutual UFO Network asked the Aurora cemetery association for permission to exhume the body of the alien airship pilot supposedly buried in the town cemetery. The association declined. The headstone of the alien disappeared soon after.

Even though Aurora’s purported alien airship encounter is the best known today, the town never benefited much economically from the notoriety. But whether that close encounter was fact or fraud, Aurora’s Martian, who died in a most Quixotic fashion tilting at windmills, has achieved some degree of immortality through this historical marker.

Even though Aurora’s purported alien airship encounter is the best known today, the town never benefited much economically from the notoriety. But whether that close encounter was fact or fraud, Aurora’s Martian, who died in a most Quixotic fashion tilting at windmills, has achieved some degree of immortality through this historical marker.

And the mysteries of airship April live on.

Are you for real? Over 4000 news articles from around the world some with 1890s photograph have documented airship of different designs. Debunker have this incredible ability to take one ‘fact’ and claim for every single thing they are debunking. Oddily the information they are trying to debunk provide research, pictures, and historical facts for their information. Do you know Jesus was born in March not December. So the bible should be debunk along with airships.