The Trinity River has been a flood threat to Fort Worth ever since the town expanded from the fort on the bluff down onto lower ground.

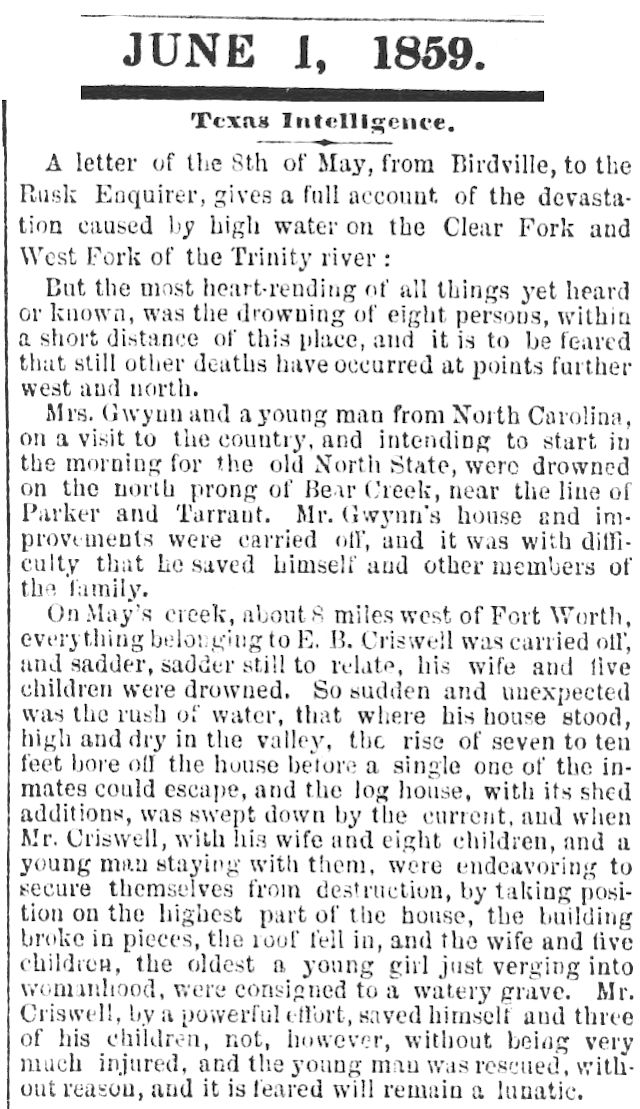

For example, a letter from Birdville to the Rusk Enquirer, reprinted in the June 1, 1859 New Orleans Crescent, describes a flood that killed eight persons. “May’s Creek” is Mary’s Creek southwest of Fort Worth. Bear Creek is south of Mary’s Creek. Both flow into the Clear Fork of the Trinity River.

For example, a letter from Birdville to the Rusk Enquirer, reprinted in the June 1, 1859 New Orleans Crescent, describes a flood that killed eight persons. “May’s Creek” is Mary’s Creek southwest of Fort Worth. Bear Creek is south of Mary’s Creek. Both flow into the Clear Fork of the Trinity River.

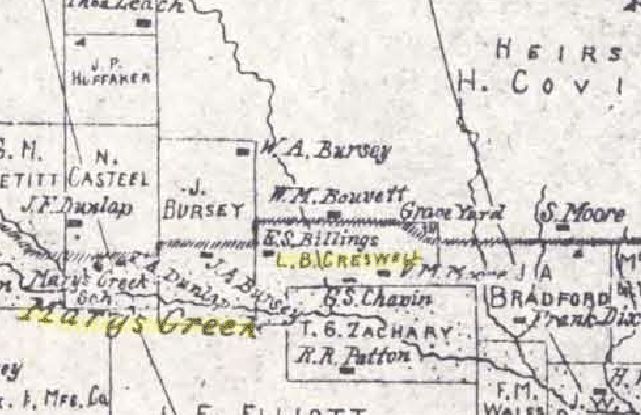

An 1895 county map shows a Creswell survey on Mary’s Creek between the four- and five-mile radius markers from the courthouse. The map also show a cemetery north of the creek. That is probably Jackson Cemetery on Chapin Road next to Leonard Middle School. The cemetery was established in 1867 on land owned by banker and rancher John L. Jackson, who died in 1919.

An 1895 county map shows a Creswell survey on Mary’s Creek between the four- and five-mile radius markers from the courthouse. The map also show a cemetery north of the creek. That is probably Jackson Cemetery on Chapin Road next to Leonard Middle School. The cemetery was established in 1867 on land owned by banker and rancher John L. Jackson, who died in 1919.

Of the four Fort Worth floods severe enough and recent enough to have been well documented, the flood of 1889 was the first.

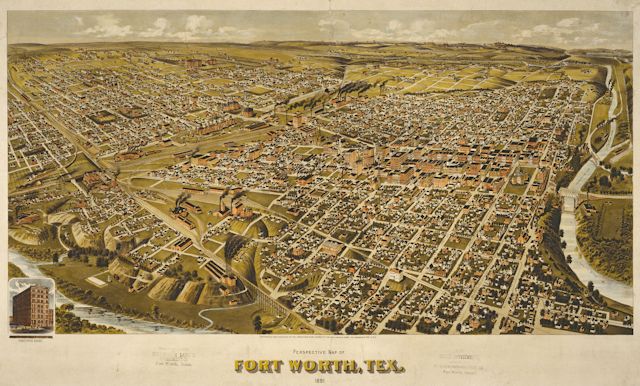

Fort Worth’s population in 1889 was about twenty-three thousand. This bird’s-eye-view map by the American Publishing Company shows the extent of the city in 1891.

Fort Worth’s population in 1889 was about twenty-three thousand. This bird’s-eye-view map by the American Publishing Company shows the extent of the city in 1891.

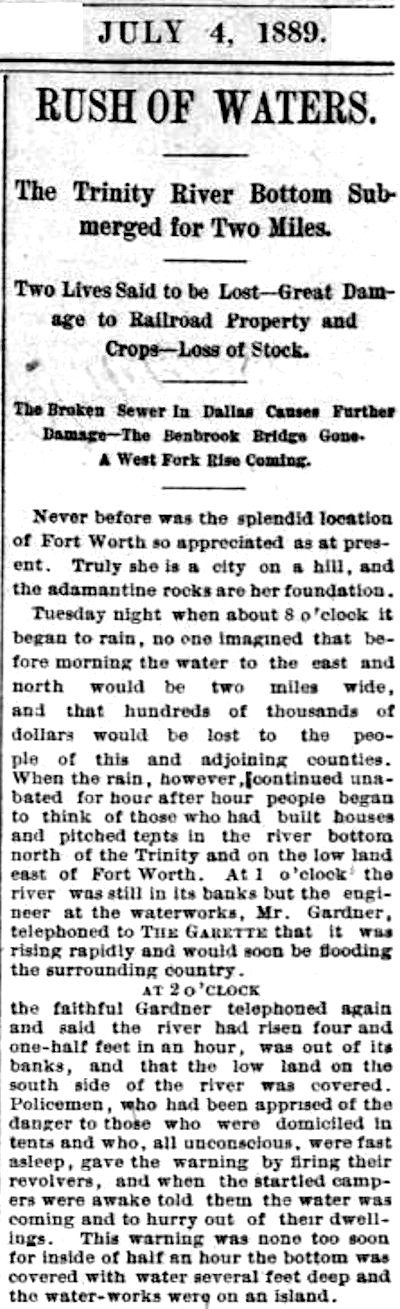

About 8 p.m. on July 2, 1889 rain began to fall. By 2 a.m. July 4 the Trinity River was out of its banks. Policemen began firing their pistols to warn sleeping people in low areas, especially people living in tents on the river bottom north and east of downtown. The river bottom was a temporary refuge for people who could not afford to live anywhere else. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

About 8 p.m. on July 2, 1889 rain began to fall. By 2 a.m. July 4 the Trinity River was out of its banks. Policemen began firing their pistols to warn sleeping people in low areas, especially people living in tents on the river bottom north and east of downtown. The river bottom was a temporary refuge for people who could not afford to live anywhere else. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

Downtown’s location on high ground—thank you, Major Arnold—kept it well drained during the heavy rainfall. In fact, the Spring Palace exhibition reported its best attendance of the season on its closing day, July 4. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

Downtown’s location on high ground—thank you, Major Arnold—kept it well drained during the heavy rainfall. In fact, the Spring Palace exhibition reported its best attendance of the season on its closing day, July 4. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

But below the bluff, the river was rising. As always, flooding was worst on the west, north, and east sides. In the Samuels Avenue area even the driving park was flooded.

But below the bluff, the river was rising. As always, flooding was worst on the west, north, and east sides. In the Samuels Avenue area even the driving park was flooded.

By 3 a.m. July 4 the water was rising on the north side of the river. The North Side was not yet part of the city, but 2,500 acres of land there had been platted for development the year before. People lived there in small frame houses, even tents. They began to evacuate their homes, heading for higher ground via the iron viaduct connecting the North Side to “the city.” The iron viaduct (visible in the bird’s-eye-view map) was replaced in 1914 by the Paddock Viaduct. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

On July 6 the Dallas Morning News reported that the north approach to the iron viaduct was damaged by the flood.

On July 6 the Dallas Morning News reported that the north approach to the iron viaduct was damaged by the flood.

Flood victims were given shelter on the courthouse square. Attorney Robert McCart and alderman J. P. Nicks were among civic leaders organizing aid. A concert was planned to benefit flood victims. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

Flood victims were given shelter on the courthouse square. Attorney Robert McCart and alderman J. P. Nicks were among civic leaders organizing aid. A concert was planned to benefit flood victims. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

The flood wreaked havoc on railroad service to the east, west, and north. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

The flood wreaked havoc on railroad service to the east, west, and north. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

By 9 p.m. July 4 the Clear Fork was back in its banks, and the West Fork was falling. As always, the waterworks on the western edge of downtown was threatened because of its low location next to the river. But the waterworks was kept in operation by a flotilla of boats that shuttled in coal to keep the steam pumps operating. Clip is from the July 5 Gazette.

By 9 p.m. July 4 the Clear Fork was back in its banks, and the West Fork was falling. As always, the waterworks on the western edge of downtown was threatened because of its low location next to the river. But the waterworks was kept in operation by a flotilla of boats that shuttled in coal to keep the steam pumps operating. Clip is from the July 5 Gazette.

By early July 5 water was receding on the North Side. The people who lived in tents in the river bottom returned to survey the damage. Clip is from the July 6 Gazette.

By early July 5 water was receding on the North Side. The people who lived in tents in the river bottom returned to survey the damage. Clip is from the July 6 Gazette.

The Gazette interviewed some longtime residents, some of whom said the flood water of 1866 had risen higher than the flood water of 1889. The Gazette pointed out that Fort Worth had been confined to a much smaller area in 1866. Floods also occurred in 1877, 1882, and 1884. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

The Gazette interviewed some longtime residents, some of whom said the flood water of 1866 had risen higher than the flood water of 1889. The Gazette pointed out that Fort Worth had been confined to a much smaller area in 1866. Floods also occurred in 1877, 1882, and 1884. Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

On July 5 the Gazette reported flooding of the farms of banker and civic leader Khleber Miller Van Zandt, who owned land where Trinity Park is today, and Captain Sam Evans, who had a large homestead a mile and a half west of the courthouse and just north of White Settlement Road.

On July 5 the Gazette reported flooding of the farms of banker and civic leader Khleber Miller Van Zandt, who owned land where Trinity Park is today, and Captain Sam Evans, who had a large homestead a mile and a half west of the courthouse and just north of White Settlement Road.

An East Side mother and her son who on July 4 had been feared dead were found alive. Apparently no one died in the flood of eighty-nine, but the loss of property—railroads, streets, bridges, homes, crops, and animals—was high. The damage to railroads and crops alone was put at $1.2 million ($30 million today). Clip is from the July 5 Gazette.

An East Side mother and her son who on July 4 had been feared dead were found alive. Apparently no one died in the flood of eighty-nine, but the loss of property—railroads, streets, bridges, homes, crops, and animals—was high. The damage to railroads and crops alone was put at $1.2 million ($30 million today). Clip is from the July 5 Gazette.

The Gazette of July 4 reported on the effect of the rain on local farmers.

The Gazette of July 4 reported on the effect of the rain on local farmers.

After the flood of eighty-nine people began to talk of flood-control measures such as levees. Engineers said the areas north and east of the river could be protected. But Fort Worth would wait sixty-seven years and suffer three more great floods—1908, 1922, 1949—before the Army Corps of Engineers would tame the river in the 1950s and 1960s by building levees and straightening and widening the channel. Clip is from the July 6 Gazette.

After the flood of eighty-nine people began to talk of flood-control measures such as levees. Engineers said the areas north and east of the river could be protected. But Fort Worth would wait sixty-seven years and suffer three more great floods—1908, 1922, 1949—before the Army Corps of Engineers would tame the river in the 1950s and 1960s by building levees and straightening and widening the channel. Clip is from the July 6 Gazette.

Posts about weather:

“Greatest Tragedy of the Century” (Part 1): “Dead Outnumbers the Living”

Winter 1930: Lake Worth Ice Capades

The Deep Freeze of Fifty-One

Texas Toast: The Summers of 1980 and 2011

The Flood of 1889: The First of the Big Four

Double Trouble: The Twofer Flood of 1915

From Beneficial to Torrential: The Flood of Twenty-Two

The Flood of Forty-Nine: People in Trees, Horses on Roofs

Deja Deluge: Forty Years On, the Flood of 1989

I have written in my great grandfather’s (Charles Burton McCafferty)journal several pages of what he witness of the 1889 flood……very descriptive……

He would not recognize “our” Trinity. It would look like the mighty Mississip to him compared to the narrow, crooked, shallow, sandbar-choked river that could not handle heavy rain in his time.