History—in particular, local history—is right under our feet. We walk over it or drive over it or past it every day. Here are three examples:

615 East 1st Street

One day while walking on East 1st Street downtown on a block almost entirely lined with condos I saw a lone holdout—a small white frame house built in 1907.

One day while walking on East 1st Street downtown on a block almost entirely lined with condos I saw a lone holdout—a small white frame house built in 1907.

In the front yard of that little house was a large cut stone, possibly an orphaned cornerstone or a carriage step—a stone used as a step when getting into and out of a horse-drawn vehicle. Looking closer, I saw that the stone had a carved inscription, but the stone was upside down and only a few letters were legible.

In the front yard of that little house was a large cut stone, possibly an orphaned cornerstone or a carriage step—a stone used as a step when getting into and out of a horse-drawn vehicle. Looking closer, I saw that the stone had a carved inscription, but the stone was upside down and only a few letters were legible.

What was the inscription on the big stone in the little yard of the little house surrounded by big condos? Ah, a mystery.

“To the reference library, Cabbie, and step on it!”

First I contacted real estate developer Tom Struhs and property owner Jesse Gaines. They told me the stone had been found across the street as houses in the 600 block of East 1st Street were demolished to build those big condos. I got permission to flip the stone right side up.

Now that the stone was reoriented, I was able to make out the initial letter H and the last four letters ARTZ. What else could the stone tell me? Channeling Vanna White, I filled in the blanks between the H and the ARTZ. How about, oh, I dunno, four consonants? Could the carved inscription be H Schwartz?

Now that the stone was reoriented, I was able to make out the initial letter H and the last four letters ARTZ. What else could the stone tell me? Channeling Vanna White, I filled in the blanks between the H and the ARTZ. How about, oh, I dunno, four consonants? Could the carved inscription be H Schwartz?

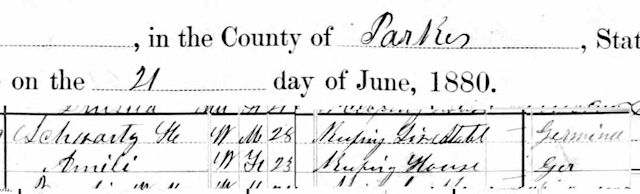

Using that guess as my “shovel,” I did some more digging. I learned that in 1880 Henry and Amili Schwartz, born in Germany, were living in Parker County, where he operated a livery stable. So he was already in the transportation business.

Using that guess as my “shovel,” I did some more digging. I learned that in 1880 Henry and Amili Schwartz, born in Germany, were living in Parker County, where he operated a livery stable. So he was already in the transportation business.

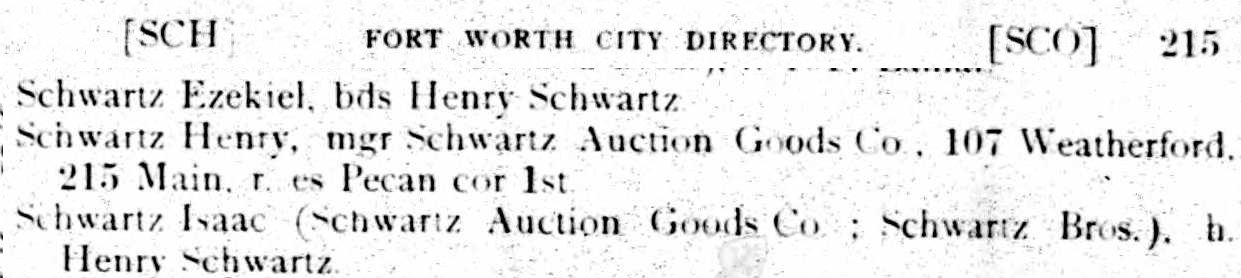

By 1888 Henry was a wholesale grocer in Fort Worth and owned an auction house on the courthouse square. The 1888 city directory lists his residence at the corner of Pecan Street and . . . wait for it . . . the 600 block of East 1st Street. Eureka!

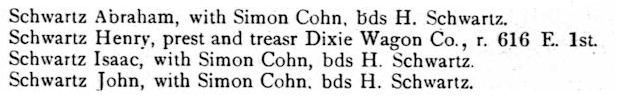

By 1892 Henry Schwartz had moved three houses east to 616 East 1st Street—directly across the street from where the carriage step sits today. Eu-double dang-reka!

By 1892 Henry Schwartz had moved three houses east to 616 East 1st Street—directly across the street from where the carriage step sits today. Eu-double dang-reka!

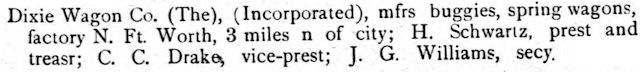

The 1892 city directory also shows that Henry Schwartz had a new business: the Dixie Wagon Company. The company had been incorporated in 1889 by Schwartz, wagon builder Ewald Henry Keller, and attorney William Capps. As president of a company that made carriages, Schwartz would naturally drive his company’s best carriage, and it makes sense that he would have a fine carriage step to go with a fine carriage.

The 1892 city directory also shows that Henry Schwartz had a new business: the Dixie Wagon Company. The company had been incorporated in 1889 by Schwartz, wagon builder Ewald Henry Keller, and attorney William Capps. As president of a company that made carriages, Schwartz would naturally drive his company’s best carriage, and it makes sense that he would have a fine carriage step to go with a fine carriage.

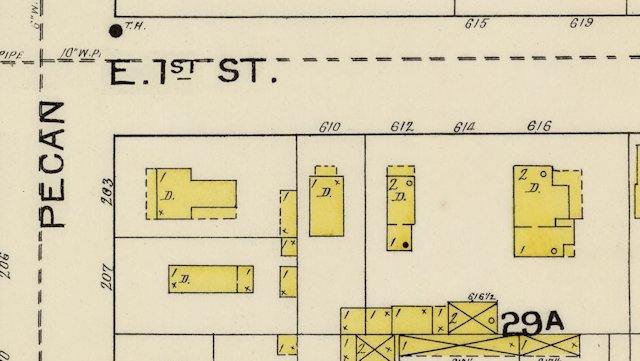

An 1893 map shows 616 East 1st Street to be a large two-story house, possibly with a carriage house at the rear (labeled “616 1/2” on the map).

An 1893 map shows 616 East 1st Street to be a large two-story house, possibly with a carriage house at the rear (labeled “616 1/2” on the map).

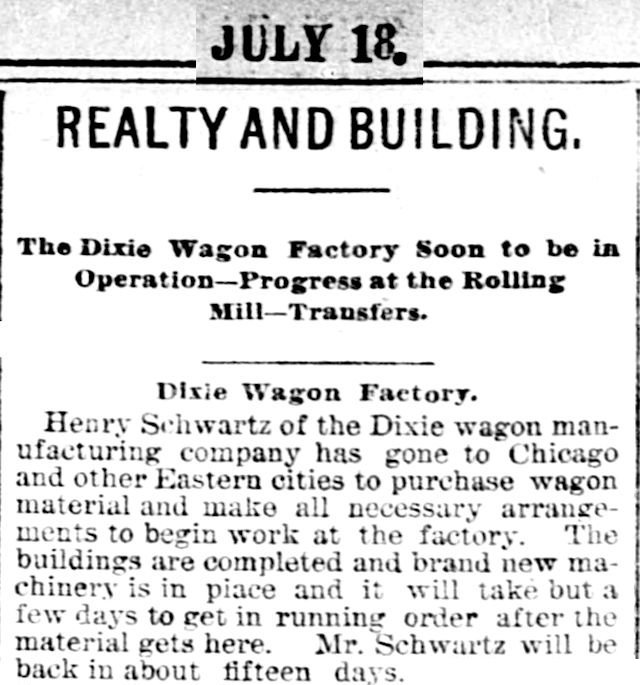

On July 18, 1890 the Gazette reported that Henry Schwartz had gone to Chicago to buy material for the Dixie Wagon Company, which was expected to begin production soon.

On July 18, 1890 the Gazette reported that Henry Schwartz had gone to Chicago to buy material for the Dixie Wagon Company, which was expected to begin production soon.

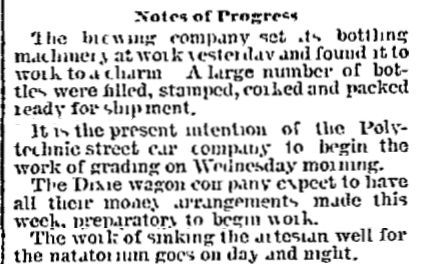

That didn’t happen right away because on June 23, 1891 the Gazette reported that the Dixie Wagon Company was still finalizing its financing. Meanwhile, the Texas Brewing Company and Natatorium had just opened, and the Polytechnic streetcar line was under construction.

That didn’t happen right away because on June 23, 1891 the Gazette reported that the Dixie Wagon Company was still finalizing its financing. Meanwhile, the Texas Brewing Company and Natatorium had just opened, and the Polytechnic streetcar line was under construction.

One way by which companies such as the Dixie Wagon Company raised startup money was by buying more land than they needed for their factory, platting the surplus land into lots, and selling lots. The Dixie Wagon addition on the North Side quickly became a Monopoly board of buyers and sellers. For example, on October 15, 1891 the Gazette reported that Dixie sold lots to the Democrat newspaper company. And William H. Ward, proprietor of the White Elephant, sold a Dixie Wagon lot to Henry’s wife Amili. Today people still live in Dixie Wagon addition. Note that there is a Schwartz Street.

One way by which companies such as the Dixie Wagon Company raised startup money was by buying more land than they needed for their factory, platting the surplus land into lots, and selling lots. The Dixie Wagon addition on the North Side quickly became a Monopoly board of buyers and sellers. For example, on October 15, 1891 the Gazette reported that Dixie sold lots to the Democrat newspaper company. And William H. Ward, proprietor of the White Elephant, sold a Dixie Wagon lot to Henry’s wife Amili. Today people still live in Dixie Wagon addition. Note that there is a Schwartz Street.

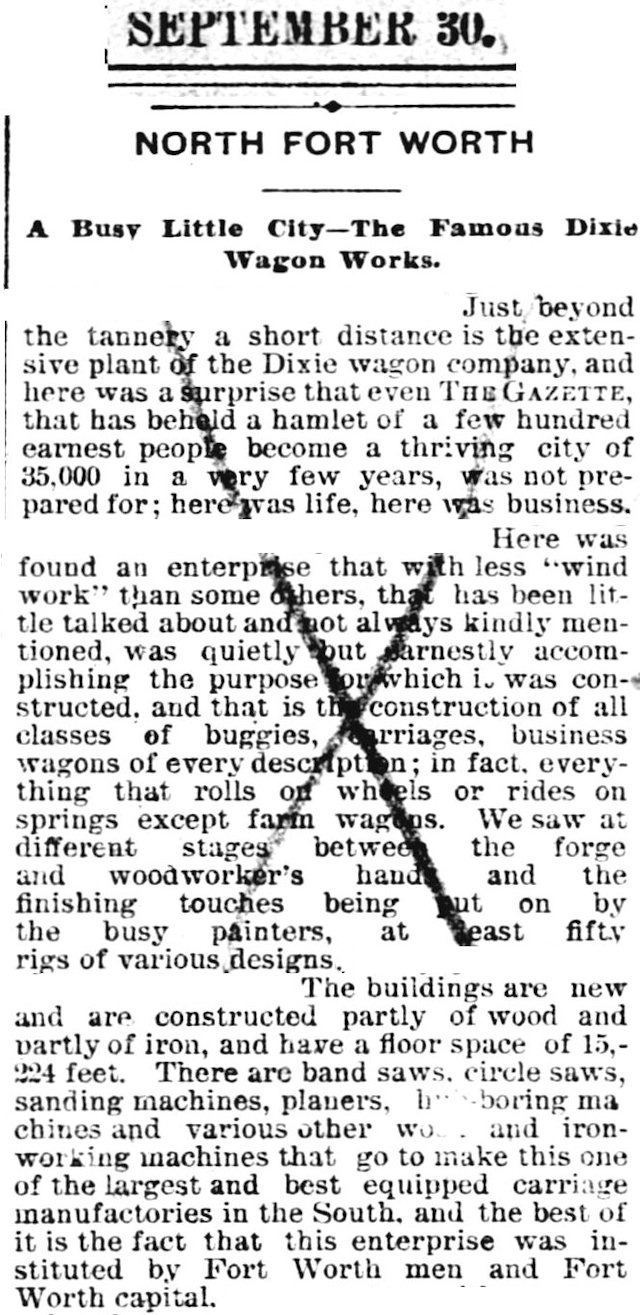

On September 30, 1891 the Gazette printed what appears to be a news report but reads like an advertisement after a “scribe” toured the new wagon factory.

On September 30, 1891 the Gazette printed what appears to be a news report but reads like an advertisement after a “scribe” toured the new wagon factory.

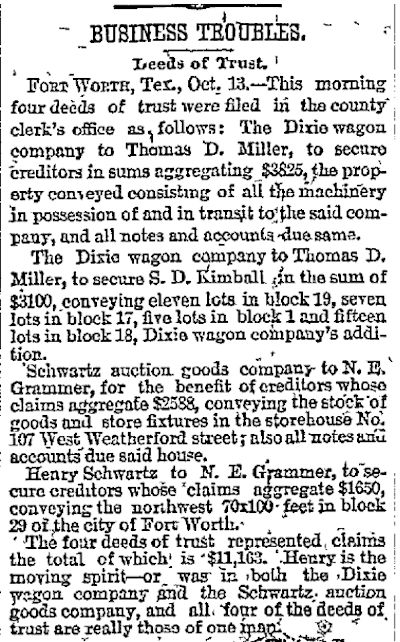

But on October 14, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported that on the previous day Henry Schwartz had surrendered title to the Dixie Wagon Company and his auction company to settle debts totaling $11,163 ($280,000 today). By 1895 neither the Dixie Wagon Company nor Henry Schwartz appeared in the city directory.

But on October 14, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported that on the previous day Henry Schwartz had surrendered title to the Dixie Wagon Company and his auction company to settle debts totaling $11,163 ($280,000 today). By 1895 neither the Dixie Wagon Company nor Henry Schwartz appeared in the city directory.

Today Henry Schwartz is dead. His Dixie Wagon Company is defunct. But his carriage step survives in a little yard on East 1st Street to remind passersby of the era of bustles and buggies.

1633 West 7th Street

At the northwest corner of the Educational Employees Credit Union property on West 7th Street downtown is a white retaining wall pierced by two sets of steps.

At the northwest corner of the Educational Employees Credit Union property on West 7th Street downtown is a white retaining wall pierced by two sets of steps.

The steps lead nowhere—they do not connect the sidewalk to the EECU parking lot.

The steps lead nowhere—they do not connect the sidewalk to the EECU parking lot.

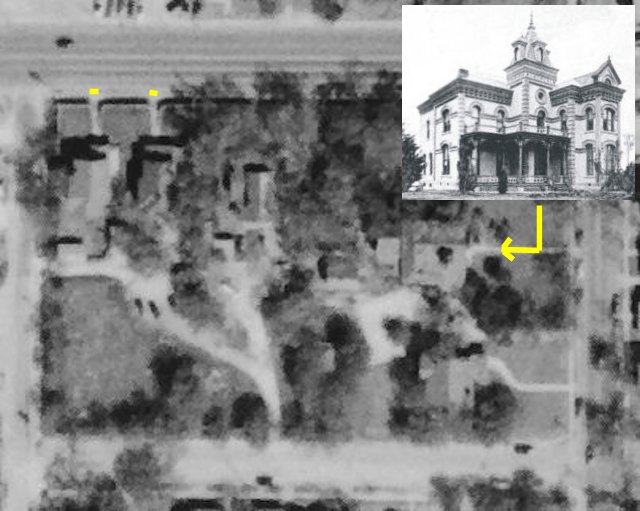

But a 1952 aerial photo shows that the steps once led to sidewalks that led to two houses at 1627 and 1633 West 7th Street. The yellow dashes mark the steps. The two houses were substantial, being on the gilded edge of Quality Hill. In fact, civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt’s house, with its grand tower, still stood just around the corner on Penn Street where the EECU building is today (see inset). Indeed, the legal description of the EECU lot is “Van Zandt Homesite Major Blk A Lot 1.” The Van Zandt house was demolished in the 1960s.

But a 1952 aerial photo shows that the steps once led to sidewalks that led to two houses at 1627 and 1633 West 7th Street. The yellow dashes mark the steps. The two houses were substantial, being on the gilded edge of Quality Hill. In fact, civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt’s house, with its grand tower, still stood just around the corner on Penn Street where the EECU building is today (see inset). Indeed, the legal description of the EECU lot is “Van Zandt Homesite Major Blk A Lot 1.” The Van Zandt house was demolished in the 1960s.

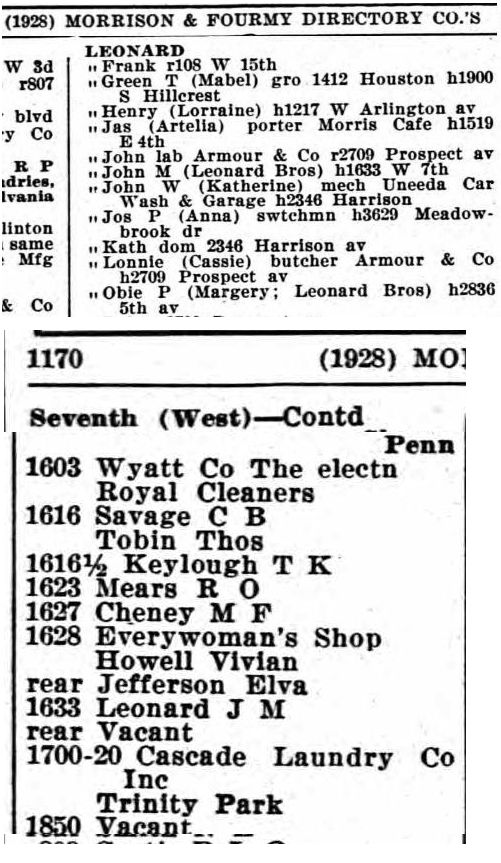

In 1928 the occupant of the house at 1633 West 7th Street was none other than John Marvin Leonard, founder of Leonard’s Department Store. In 1928 the Leonard’s store had been open ten years but still was of modest scale. As the store grew into a mercantile empire, Marvin Leonard moved west from 1633 West 7th Street. In 1936 he would build a mansion on Alta Drive facing River Crest Country Club.

In 1928 the occupant of the house at 1633 West 7th Street was none other than John Marvin Leonard, founder of Leonard’s Department Store. In 1928 the Leonard’s store had been open ten years but still was of modest scale. As the store grew into a mercantile empire, Marvin Leonard moved west from 1633 West 7th Street. In 1936 he would build a mansion on Alta Drive facing River Crest Country Club.

The house at 1627 West 7th was demolished in the 1960s; the Leonard house at 1633 West 7th was demolished in the 1970s. Their steps have survived, perhaps because they are part of the retaining wall. EECU did not return my phone calls, so I can offer no insight into how the steps that once led to somewhere have survived to lead to nowhere.

1401 Stella Street

In 1903 the International & Great Northern railway began serving Fort Worth and built its rail yard where today Stella Street intersects Vickery Boulevard in Glenwood.

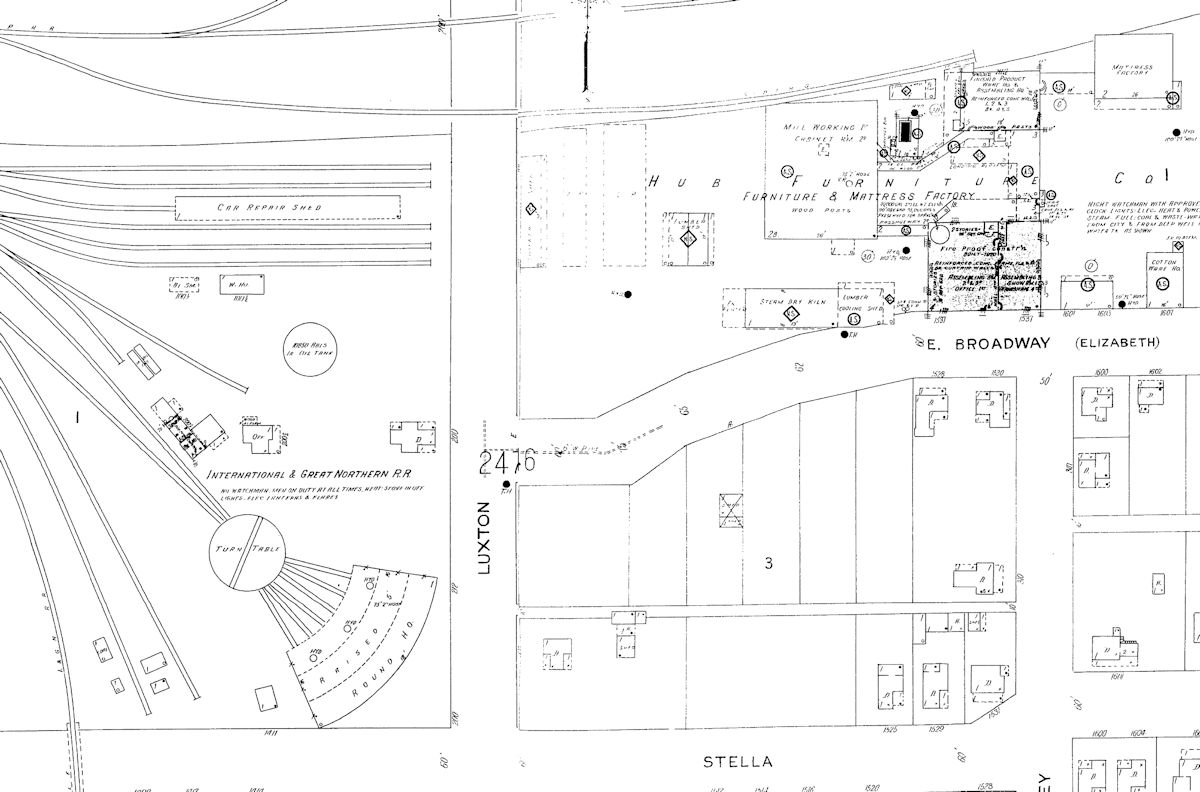

I&GN’s semicircular roundhouse (for servicing its locomotives) was located at the corner of Stella and Luxton streets. The round turntable (for rotating its locomotives) was located just northwest of the roundhouse. In this 1926 map the Hub Furniture Company was located to the immediate east of the rail yard. Note the building in the upper-right corner of this map.

I&GN’s semicircular roundhouse (for servicing its locomotives) was located at the corner of Stella and Luxton streets. The round turntable (for rotating its locomotives) was located just northwest of the roundhouse. In this 1926 map the Hub Furniture Company was located to the immediate east of the rail yard. Note the building in the upper-right corner of this map.

The building in the upper-right corner of the 1926 map is the Hub mattress factory building. As one of the area’s few surviving landmarks, it will serve as our point of reference.

The building in the upper-right corner of the 1926 map is the Hub mattress factory building. As one of the area’s few surviving landmarks, it will serve as our point of reference.

This aerial photo from 1939 shows the I&GN roundhouse in the upper left. The Hub building is in the lower right. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library)

This aerial photo from 1939 shows the I&GN roundhouse in the upper left. The Hub building is in the lower right. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library)

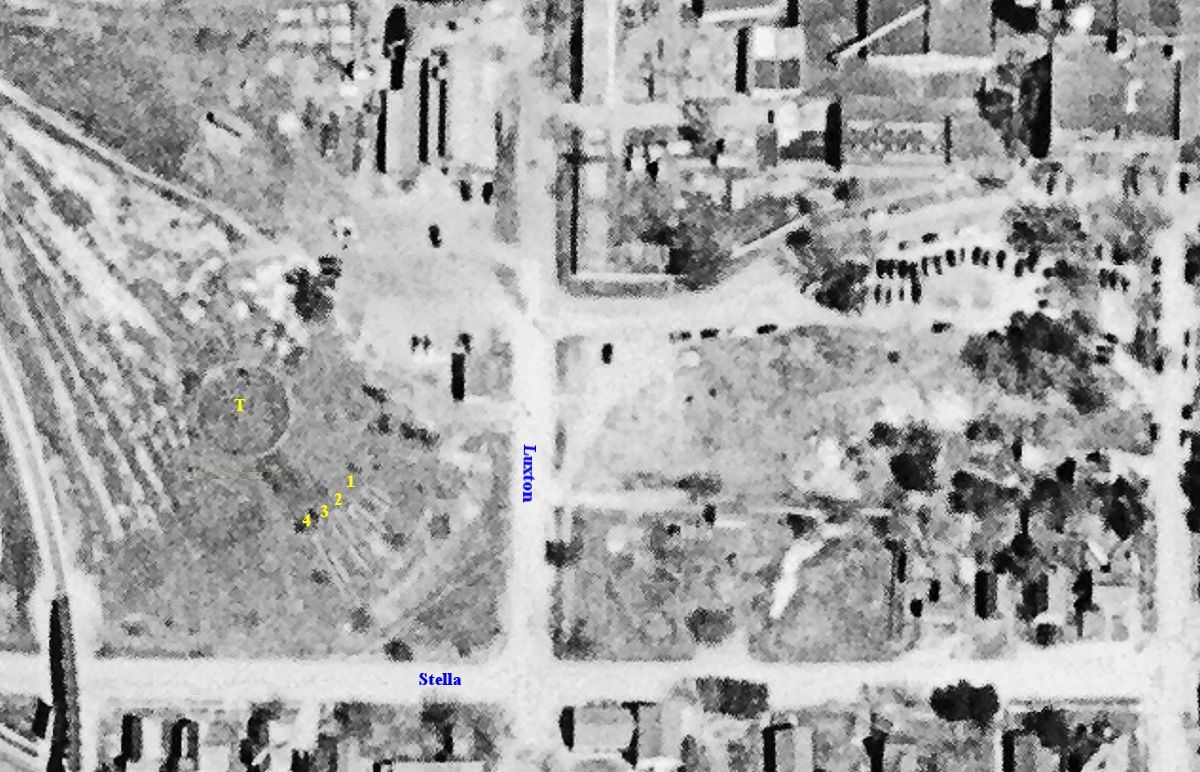

By 1952 the I&GN rail yard was gone. But in this 1952 aerial photo the round footprint of the turntable (T) can still be seen. Southeast of the turntable circle can be seen the concrete pads of four locomotive stalls of the semicircular roundhouse. The Hub mattress factory building is in the upper right. In the lower left is the trestle over Stella Street.

By 1952 the I&GN rail yard was gone. But in this 1952 aerial photo the round footprint of the turntable (T) can still be seen. Southeast of the turntable circle can be seen the concrete pads of four locomotive stalls of the semicircular roundhouse. The Hub mattress factory building is in the upper right. In the lower left is the trestle over Stella Street.

Today, another sixty years later, all vestiges of the I&GN rail yard are gone.

Or are they?

One day as I was hovering over the area via Google aerial maps, I noticed something. The old rail yard site is now occupied by Lone Star Metals and W. Pat Crow Forgings. To the right of the Lone Star Metals building I saw an arc, as if part of a large circle. Looking at the 1926 map and the 1952 aerial photo, the location of the arc seemed to coincide with the location of the I&GN turntable. Compare the location of the arc relative to (1) the location of the turntable, (2) the location of the Hub mattress factory building, and (3) the intersection of Stella and Luxton streets in the 1926 map and 1952 aerial photo.

One day as I was hovering over the area via Google aerial maps, I noticed something. The old rail yard site is now occupied by Lone Star Metals and W. Pat Crow Forgings. To the right of the Lone Star Metals building I saw an arc, as if part of a large circle. Looking at the 1926 map and the 1952 aerial photo, the location of the arc seemed to coincide with the location of the I&GN turntable. Compare the location of the arc relative to (1) the location of the turntable, (2) the location of the Hub mattress factory building, and (3) the intersection of Stella and Luxton streets in the 1926 map and 1952 aerial photo.

And now look back at the 1952 aerial photo and then at this recent satellite photo and an enlargement of the property just southeast of what I think is the perimeter of the turntable. At the corner of Stella and Luxton streets those surely are the concrete pads of three locomotive stalls of the roundhouse.

Can we thus conclude that at least part of the I&GN turntable and part of the roundhouse—genuine relics of the steam age—survive?

I think we can, I think we can, I think we can. But Lone Star Metals and W. Pat Crow Forgings would not allow me on the premises unless I wanted to sell some beer cans or buy five hundred piston rods. So, for now, we can but stare through the chain-link fence at the history that may be right under our feet.

Hi! Cool stuff. Thanks for sharing and makes for interesting reading. I’ve been plotting old turntable/roundhouse sites across Texas and stumbled across your site while googling around. Some 2013 and later aerial imagery suggests that the I&GN roundhouse stall foundations may still exist.

Thanks, Bruce. You’re right-aerial photos later than those I used do show what I think is the perimeter of the turntable and the footprints of three locomotive stalls of the roundhouse. I have updated this post and my posts on the I&GN and on turntables and roundhouses.

awesome and very educational as well. Thank you for all your great research.

Thanks, Fred. Sometimes the most interesting subjects are those I come across by accident.

Once again great stuff Mike! Very fascinating.

Thanks, Keith.

http://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/files/original/73eb61f5eb87241dc18647830ec824d9.jpg

From the UTA digital gallery, a 1939 view of E Lancaster that includes the I&GN yard. Also the interurban right of way, which must have just been abandoned.

What a great photo. Aerials before 1952 are rare. You can pick details out of this one until you get eye strain: Near I&GN are Hub furniture company and the ill-fated North Glenwood subdivision. Then there’s the roadbed of both interurban lines (including the underpass for the Cleburne line at the T&P tracks, which some of us have looked for), Sycamore Creek, Waples Platter, I. M. Terrell, the bus barn, Missouri Avenue church, the old high school on Jennings, West Van Zandt school, the new West Lancaster bridge, Rall grain elevator, GM plant, Ward’s, Harris Hospital, Will Rogers, etc. Thanks.

I got it: The steps went to an Aztec-type temple.

Let’s buy those piston rods or drink up a case of beer and sell the cans. The Capps name keeps coming up. As for the steps, probably an underground bunker in the area. There are service tunnels running up and down, under the sidewalks downtown. You may have seen the service elevator doors on the sidewalks. Keep up the good work, Mike, look under those rocks, peek in those closets. Mike Wallace would have.

Thanks, Earl. As for the suspected railroad turntable, I am considering a caper to get a peek at it up close, a caper involving a helicopter, the cast of the movie Ocean’s Eleven, and a large magnet.