It is the story of one remarkable place and two remarkable men.

The place: Hell’s Half Acre.

The men: police officer William A. Campbell and saloon owner Robert P. Hammond. One man was remarkable for enforcing the law, the other for breaking the law.

The men: police officer William A. Campbell and saloon owner Robert P. Hammond. One man was remarkable for enforcing the law, the other for breaking the law.

William Addison (“Ad”) Campbell, who had been on the police force only a few months in 1909, nonetheless pounded the toughest beat in town—the Acre. But Campbell was not intimidated. In the contest of Ad Campbell against Hell’s Half Acre, Campbell felt that the Acre was the underdog.

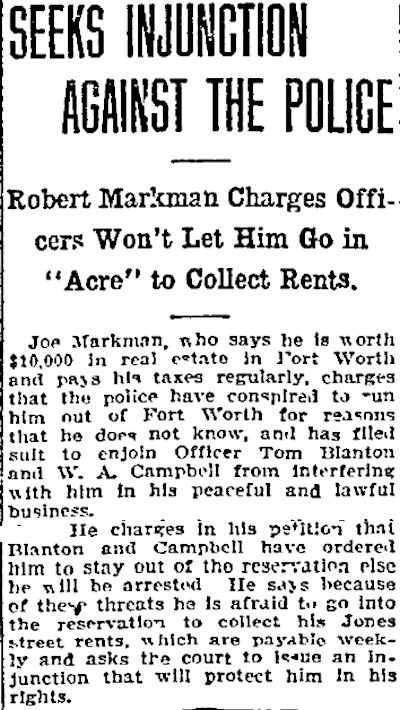

Even into the early twentieth century the Acre remained a rough place, and police employed law enforcement methods there that today would bring lawsuits and protests. This July 9, 1909 Star-Telegram clip says Acre slumlord Robert Markham sought an injunction against Campbell and another officer who, Markham claimed, would not allow him to collect his rents on Jones Street tenements.

Even into the early twentieth century the Acre remained a rough place, and police employed law enforcement methods there that today would bring lawsuits and protests. This July 9, 1909 Star-Telegram clip says Acre slumlord Robert Markham sought an injunction against Campbell and another officer who, Markham claimed, would not allow him to collect his rents on Jones Street tenements.

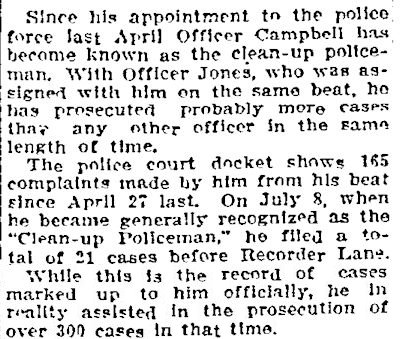

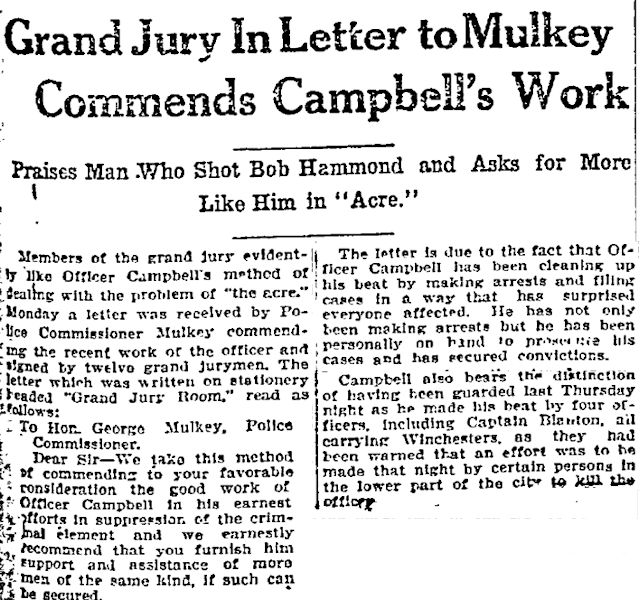

Campbell pounded his beat with the zeal of a reformer. Clip is from the August 13 Star-Telegram.

Campbell pounded his beat with the zeal of a reformer. Clip is from the August 13 Star-Telegram.

Yes, officer Campbell knew no fear. His superiors, on the other hand, did know fear: the fear that Campbell’s zeal would get him killed on the beat. In fact, Campbell made so many enemies with his by-the-book policing of the Acre that his superiors on more than one occasion assigned other officers to guard him as he walked his beat.

Yes, officer Campbell knew no fear. His superiors, on the other hand, did know fear: the fear that Campbell’s zeal would get him killed on the beat. In fact, Campbell made so many enemies with his by-the-book policing of the Acre that his superiors on more than one occasion assigned other officers to guard him as he walked his beat.

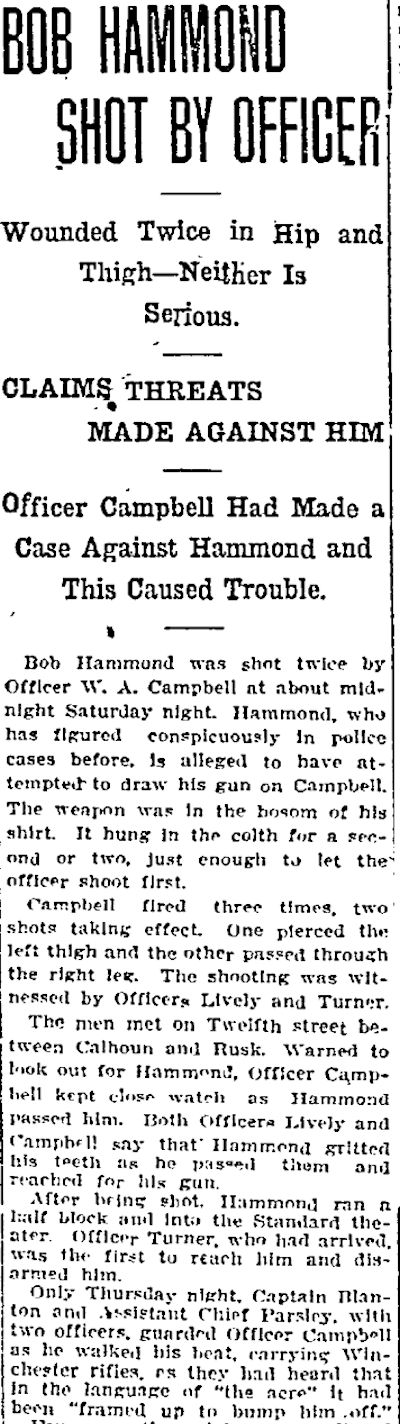

On July 10, 1909 Campbell, with two “guardian angel” officers in tow, was walking down 12th Street between Rusk (Commerce Street today) and Calhoun streets when he passed Bob Hammond, owner of a saloon on East 13th Street at Jones Street on the fringe of the Acre. On the mean streets of the Acre, Bob Hammond managed to stand out as gratuitously mean. Campbell had been warned about Hammond. As the saloon owner walked past Campbell and the other two officers, the two guardian angels were close enough to Hammond to later claim that Hammond “gritted his teeth . . . and reached for his gun.”

In response, Campbell drew his gun and shot at Hammond three times, hitting him twice—once in each leg. Despite such wounds, Hammond ran to the Standard Theater, where he was arrested and “disarmed.” Although the newspaper story says Hammond was carrying a gun, historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster, in their Written in Blood (Volume 1), write that Hammond did not have a gun on him. Note that the news story says that on the previous Thursday night, four officers had accompanied Campbell on his beat because police had heard that an attempt would be made on Campbell’s life. Clip is from the July 11 Star-Telegram.

On July 13 the Star-Telegram printed a commendation from the grand jury, saying the Acre needed more officers like Ad Campbell.

On July 13 the Star-Telegram printed a commendation from the grand jury, saying the Acre needed more officers like Ad Campbell.

One month later, about 9:40 p.m. on August 12, officer Campbell, with officer Tom Jones tagging along, walked past the window of a room above the Jockey Club saloon at 1315 Rusk Street in the Acre. A single blast from a shotgun fired from the window peppered Campbell with buckshot, killing him.

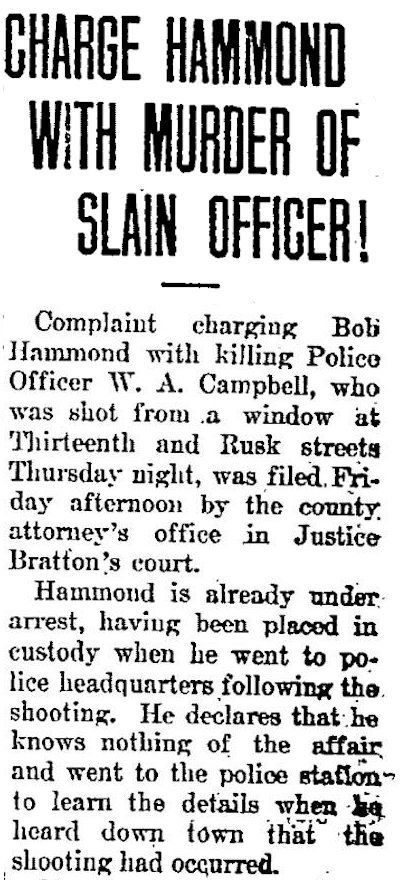

Minutes later Bob Hammond went to the police station—to learn more about the shooting, he claimed—and was arrested for the murder of Campbell. Clip is from the August 13 Star-Telegram.

Minutes later Bob Hammond went to the police station—to learn more about the shooting, he claimed—and was arrested for the murder of Campbell. Clip is from the August 13 Star-Telegram.

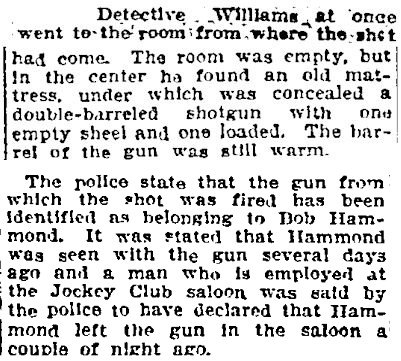

Police quickly built a case of circumstantial evidence against Hammond. Police searched the room above the Jockey Club and found a “still warm” double-barreled shotgun. One barrel contained a spent shell. The other barrel contained a shell loaded with no. 7 buckshot—the charge that had killed officer Campbell. Police also said that the shotgun used in the killing was owned by Hammond and that Hammond had left the shotgun in the Jockey Club “a couple of nights ago.”

Police quickly built a case of circumstantial evidence against Hammond. Police searched the room above the Jockey Club and found a “still warm” double-barreled shotgun. One barrel contained a spent shell. The other barrel contained a shell loaded with no. 7 buckshot—the charge that had killed officer Campbell. Police also said that the shotgun used in the killing was owned by Hammond and that Hammond had left the shotgun in the Jockey Club “a couple of nights ago.”

Selcer and Foster write that Hammond claimed (1) that he had merely gotten the shotgun out of pawn for another man and (2) that he did not know what had become of the shotgun. Clip is from the August 13 Star-Telegram.

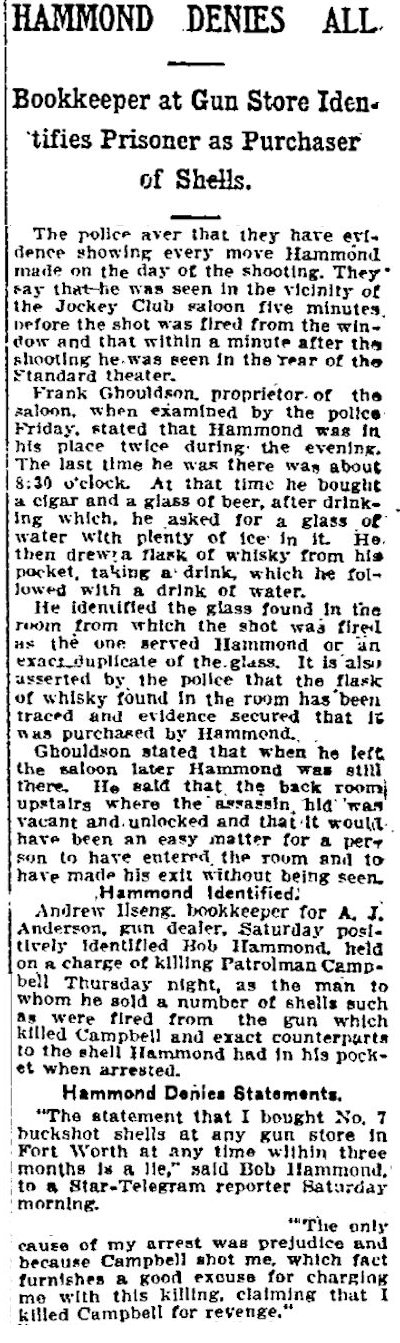

The Jockey Club proprietor said Hammond had been in the saloon about 8:30 on the night of the ambush, had ordered a glass of water, and had with him a flask. The bartender identified a glass of water found in the upstairs room as the glass that Hammond had or a duplicate of Hammond’s glass. Police said a flask found in the room had been bought by Hammond. The flask, the glass, and cigarette butts in the room, police said, indicated that the shooter had waited at the window a while for Campbell to pass on the sidewalk below.

The Jockey Club proprietor said Hammond had been in the saloon about 8:30 on the night of the ambush, had ordered a glass of water, and had with him a flask. The bartender identified a glass of water found in the upstairs room as the glass that Hammond had or a duplicate of Hammond’s glass. Police said a flask found in the room had been bought by Hammond. The flask, the glass, and cigarette butts in the room, police said, indicated that the shooter had waited at the window a while for Campbell to pass on the sidewalk below.

The bookkeeper at A. J. Anderson’s gun shop also said Hammond had bought no. 7 buckshot shells.

Hammond denied everything and said he was a suspect only because Campbell had shot him a month earlier. Clip is from the August 14 Star-Telegram.

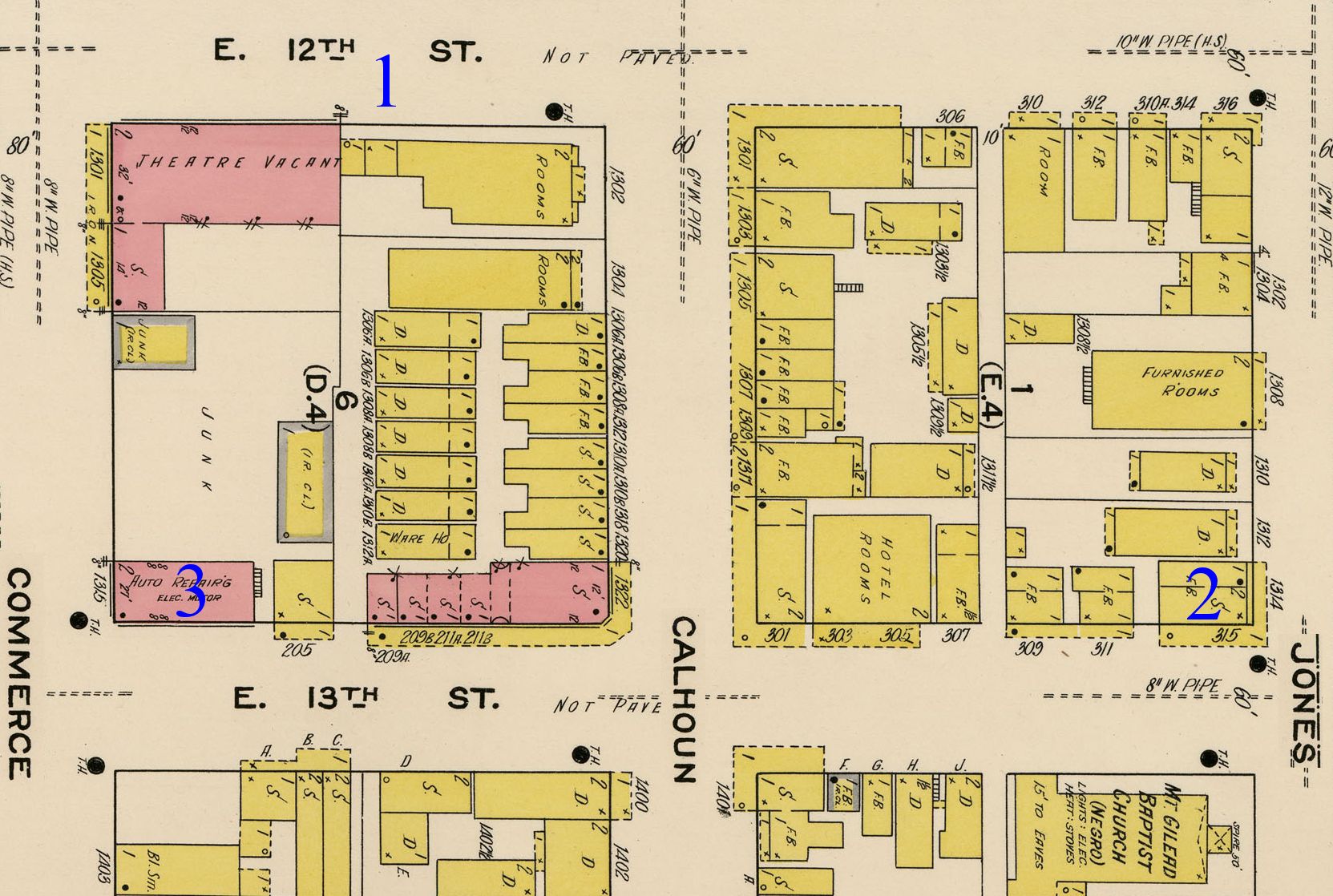

This 1910 map of the area just east of today’s convention center shows 1. where officer Campbell shot Bob Hammond on July 10, 2. Hammond’s saloon, and 3. the Jockey Club, where officer Campbell was ambushed on August 12. (By 1910 the building that had housed the Jockey Club was an auto repair shop; the building that had housed Hammond’s saloon was a “female boardinghouse,” which was a euphemism for “brothel.”)

This 1910 map of the area just east of today’s convention center shows 1. where officer Campbell shot Bob Hammond on July 10, 2. Hammond’s saloon, and 3. the Jockey Club, where officer Campbell was ambushed on August 12. (By 1910 the building that had housed the Jockey Club was an auto repair shop; the building that had housed Hammond’s saloon was a “female boardinghouse,” which was a euphemism for “brothel.”)

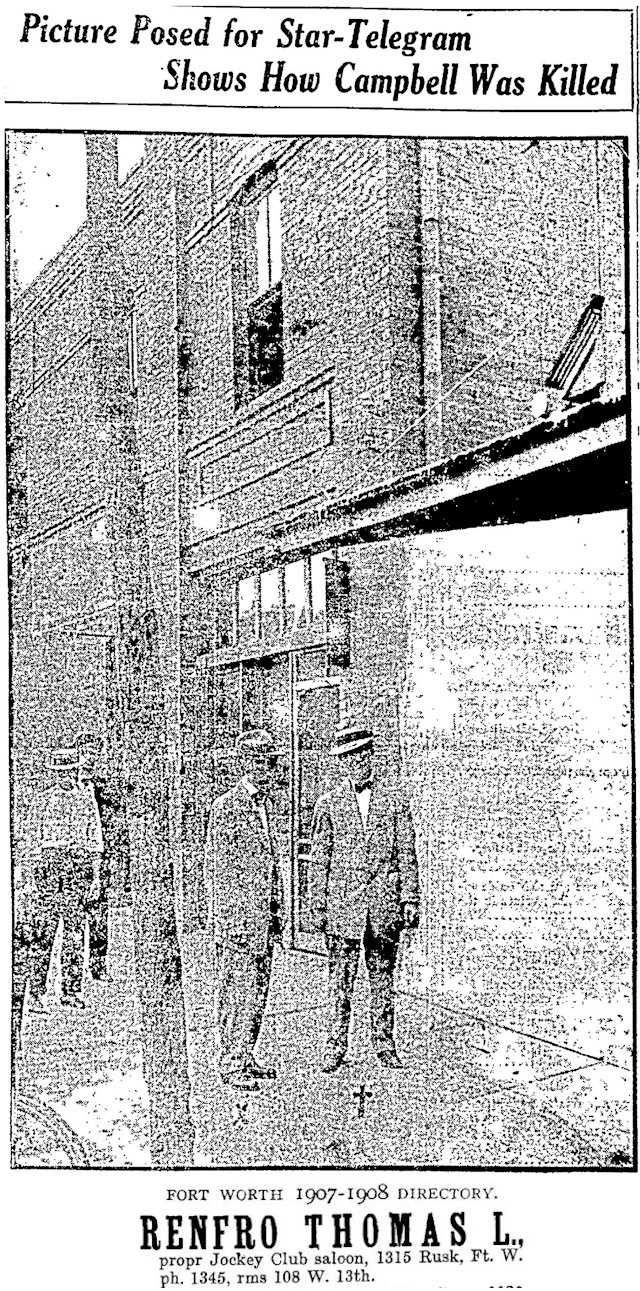

Photo from the August 13 Star-Telegram re-creating the crime scene shows the second-story window and the location of Campbell and officer Jones on the sidewalk below.

Photo from the August 13 Star-Telegram re-creating the crime scene shows the second-story window and the location of Campbell and officer Jones on the sidewalk below.

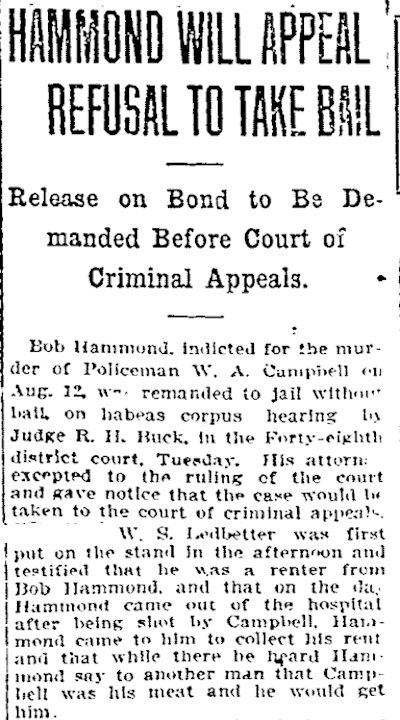

On September 8 the Star-Telegram quoted a man who said that on the day Hammond was released from the hospital after Campbell shot him, Hammond said, “Campbell was his meat and he would get him.”

On September 8 the Star-Telegram quoted a man who said that on the day Hammond was released from the hospital after Campbell shot him, Hammond said, “Campbell was his meat and he would get him.”

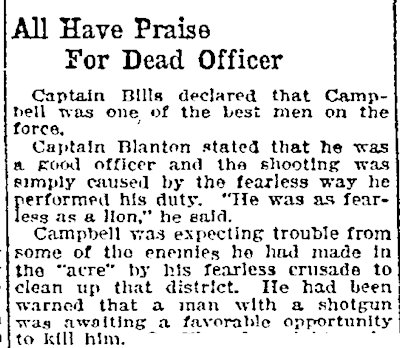

Police officers praised Campbell for his fearlessness in the August 13 Star-Telegram.

Police officers praised Campbell for his fearlessness in the August 13 Star-Telegram.

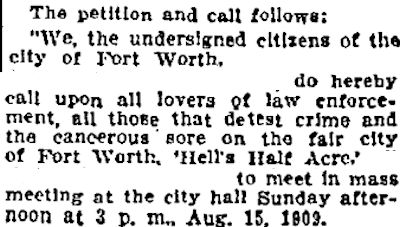

As often happened after a sensational crime in the Acre, the public reacted to the assassination of a police officer with calls to clean up the “cancerous sore.” A petition was circulated. Clip is from the August 14 Star-Telegram.

As often happened after a sensational crime in the Acre, the public reacted to the assassination of a police officer with calls to clean up the “cancerous sore.” A petition was circulated. Clip is from the August 14 Star-Telegram.

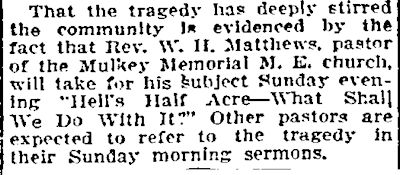

Sermons were preached. Clip is from the August 15 Star-Telegram.

Sermons were preached. Clip is from the August 15 Star-Telegram.

Resolutions were adopted. Clip is from the August 16 Star-Telegram.

Resolutions were adopted. Clip is from the August 16 Star-Telegram.

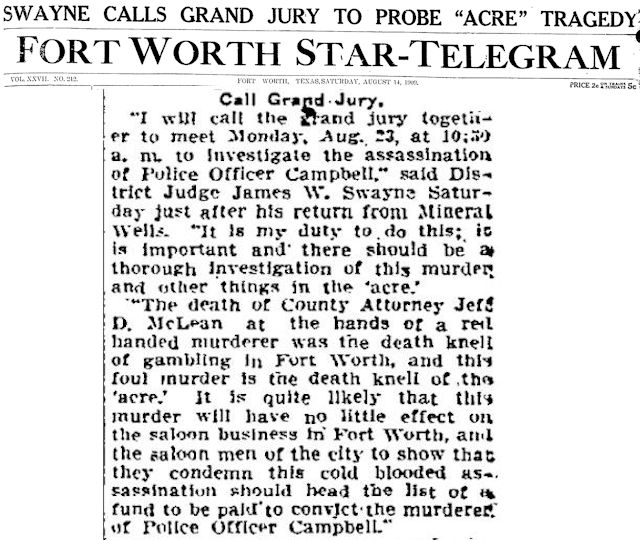

Grand juries were impaneled. On August 14 District Judge James Swayne, who had come to the legal aid of Jim Toots in 1892, said he would call a grand jury to investigate the killing of Campbell “and other things in the ‘acre.’” Swayne said that just as the murder of County Attorney Jeff McLean in 1907 had been the “death knell” of gambling in Fort Worth, so would the assassination of officer Campbell be the “death knell” of the Acre.

Grand juries were impaneled. On August 14 District Judge James Swayne, who had come to the legal aid of Jim Toots in 1892, said he would call a grand jury to investigate the killing of Campbell “and other things in the ‘acre.’” Swayne said that just as the murder of County Attorney Jeff McLean in 1907 had been the “death knell” of gambling in Fort Worth, so would the assassination of officer Campbell be the “death knell” of the Acre.

William Addison Campbell was buried in Fannin County. He was thirty-one years old.

William Addison Campbell was buried in Fannin County. He was thirty-one years old.

![]() His name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

His name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

As for Bob Hammond, accused of assassinating police officer Campbell, the state seemed to have a strong case of circumstantial evidence.

Means? Check.

Motive? Check.

Opportunity? Check.

Quick conviction? Maybe not.