After the oil strike at Ranger in 1917 Fort Worth was flush with money, and all that money had to go somewhere. Some of it went straight up into the air—in the construction of ever-taller commercial buildings. In February 1919 oilman/cattleman W. T. Waggoner announced plans for his new Waggoner Building. At a dizzying sixteen stories, the building was projected to be the tallest in the city. The next month Waggoner upped the ante: He added four stories to the plans. Now, at twenty stories, the Waggoner Building was projected to be the tallest in the state.

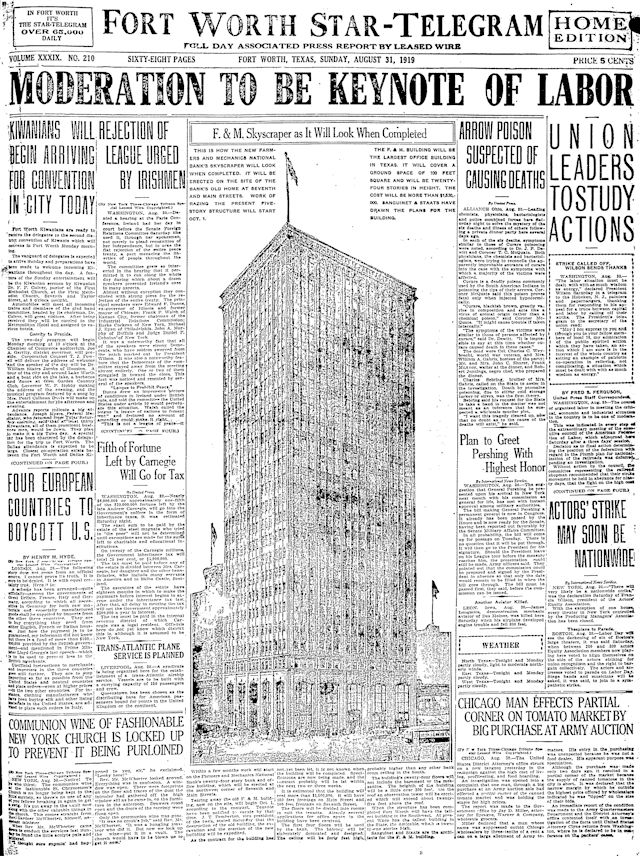

But on August 31, 1919 Farmers and Mechanics National Bank announced that it would replace its squatty little five-story building on Main at 7th Street with a building of a vertiginous twenty-four stories.

But on August 31, 1919 Farmers and Mechanics National Bank announced that it would replace its squatty little five-story building on Main at 7th Street with a building of a vertiginous twenty-four stories.

The new home of Farmers and Mechanics, the bank crowed in 1919, would be the tallest building in the state. Suddenly the Waggoner Building seemed to slouch.

For reference, this 1918 photo looks south down Main Street. The tallest building in town was probably the twelve-story State National Bank Building (Sanguinet and Staats, 1914) owned by cattleman/capitalist Burk Burnett, labeled “B.”

For reference, this 1918 photo looks south down Main Street. The tallest building in town was probably the twelve-story State National Bank Building (Sanguinet and Staats, 1914) owned by cattleman/capitalist Burk Burnett, labeled “B.”

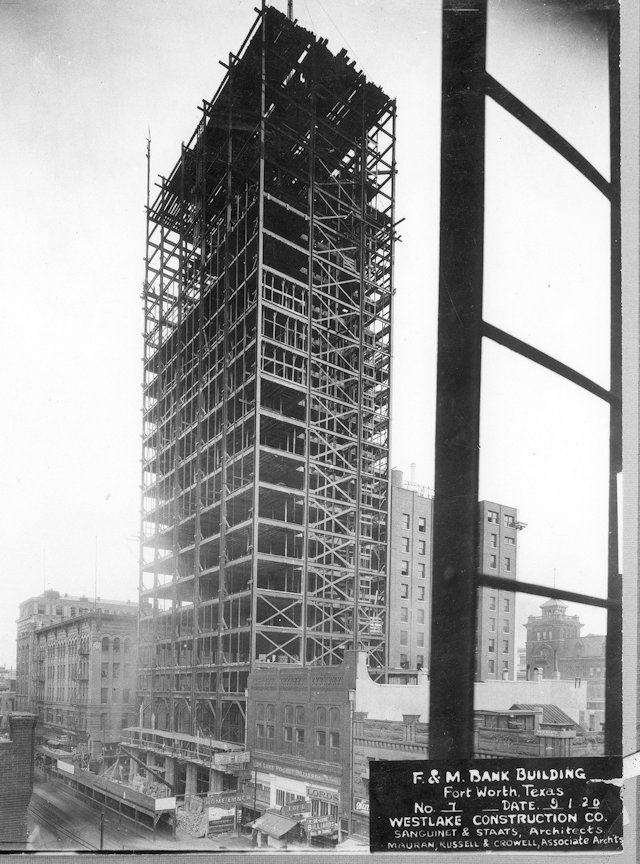

Its steel frame allowed the new F&M building to reach for the sky. To the right are First National Bank (1910) and the square tower of the Board of Trade Building (1899). (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

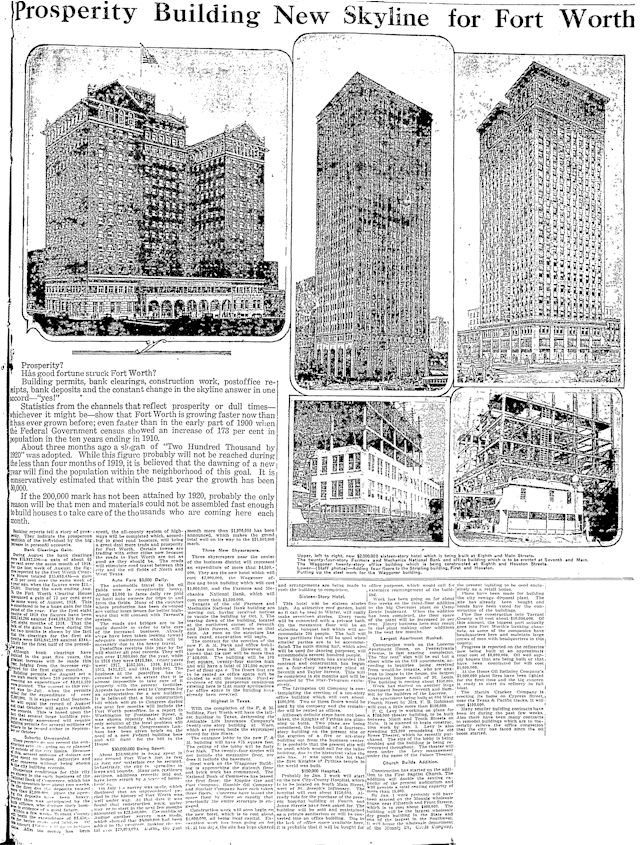

On September 28, 1919 the Star-Telegram featured three skyscrapers that were planned or under construction. Top row, from left, the Hotel Texas (sixteen stories), F&M Bank Building, Waggoner Building. All three were designed by Fort Worth’s uberarchitects, Sanguinet and Staats, as the pair entered their last decade of work. Note the preliminary C-shape footprint of the Hotel Texas, reminiscent of the Fort Worth Club Building (1926), yet another S&S design.

On September 28, 1919 the Star-Telegram featured three skyscrapers that were planned or under construction. Top row, from left, the Hotel Texas (sixteen stories), F&M Bank Building, Waggoner Building. All three were designed by Fort Worth’s uberarchitects, Sanguinet and Staats, as the pair entered their last decade of work. Note the preliminary C-shape footprint of the Hotel Texas, reminiscent of the Fort Worth Club Building (1926), yet another S&S design.

The Waggoner Building topped out first of the three, opening in August 1920. But it was top dog for only a few months because the four-more F&M building opened in May 1921. It had even a rooftop observatory from which, with a field glass, the May 15 Star-Telegram reported, “Dallas can be plainly seen on clear days.”

The Waggoner Building topped out first of the three, opening in August 1920. But it was top dog for only a few months because the four-more F&M building opened in May 1921. It had even a rooftop observatory from which, with a field glass, the May 15 Star-Telegram reported, “Dallas can be plainly seen on clear days.”

To which the overshadowed Waggoner Building probably grumbled, “Aw, who wants to see Dallas anyway?”

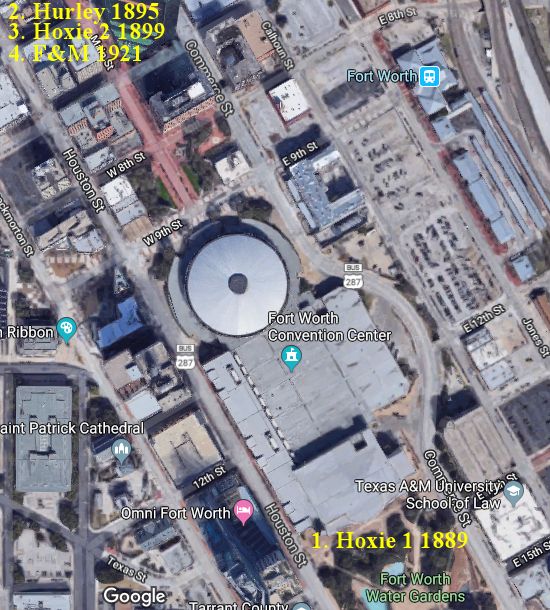

Some history: During its life of thirty-eight years, Farmers and Mechanics National Bank occupied four of Fort Worth’s grandest commercial buildings located on two sites seven blocks apart on Main Street.

(Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries Star-Telegram Collection.)

(Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries Star-Telegram Collection.)

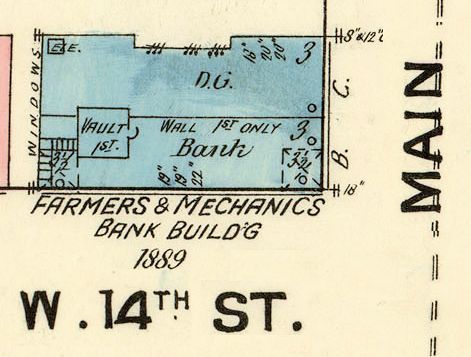

F&M’s first home was the Hoxie Building on Main Street at 14th Street in Hell’s Half Acre. This grand four-story stone building hunkered down and survived into the 1960s, when it was razed for the convention center. The building was built in 1889 by Chicago financier John Randolph Hoxie, who owned 85,000 acres of Texas ranchland and was one of the organizers of Fort Worth’s first stockyards and packing plant. Hoxie also owned a stockyards in Chicago.

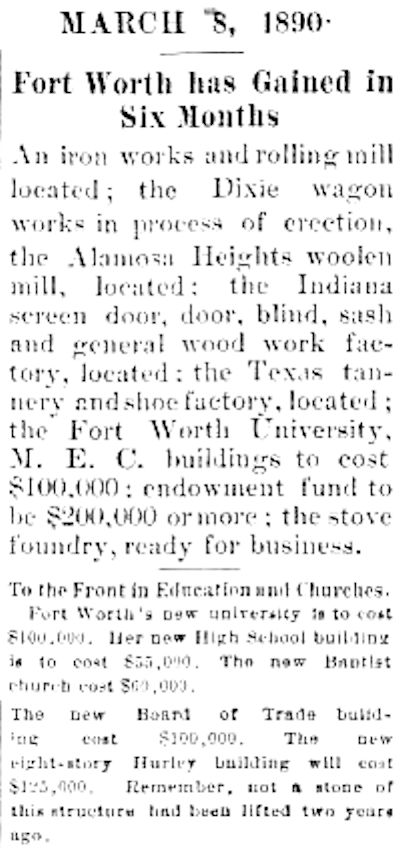

Fort Worth was booming in 1889-1890. As the Hoxie Building was going up, also planned or under construction were the Dixie wagon works, stove foundry, Fort Worth University, the high school, future cereal czar C. W. Post’s Alamosa Heights woolen mill, and the new First Baptist Church building.

Fort Worth was booming in 1889-1890. As the Hoxie Building was going up, also planned or under construction were the Dixie wagon works, stove foundry, Fort Worth University, the high school, future cereal czar C. W. Post’s Alamosa Heights woolen mill, and the new First Baptist Church building.

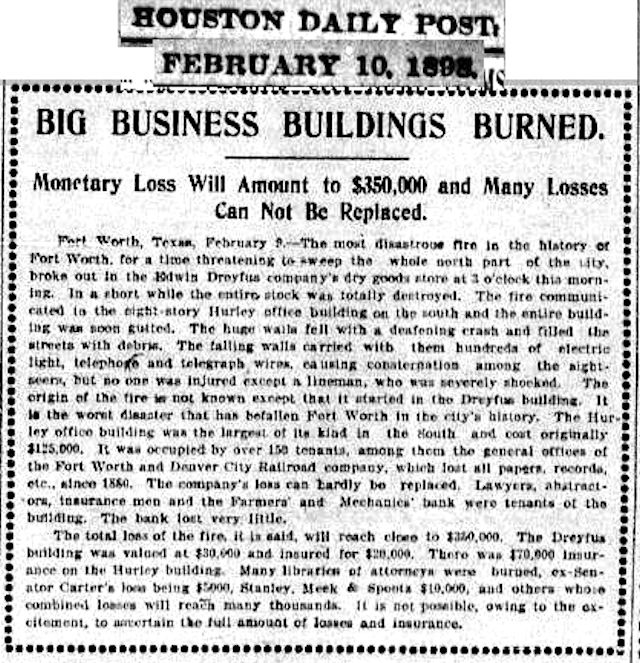

Also being built at that time was the eight-story Hurley Building, located seven blocks north of the Hoxie Building. Thomas J. Hurley, another Chicago financier, built the Hurley Building, which in 1895 became the second home of Farmers and Mechanics National Bank. The Hoxie Building in 1904 became the home of Draughon’s Practical Business College. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In 1896 John Randolph Hoxie died in Chicago and was buried there. Obituary is from the Daily Inter Ocean of Chicago.

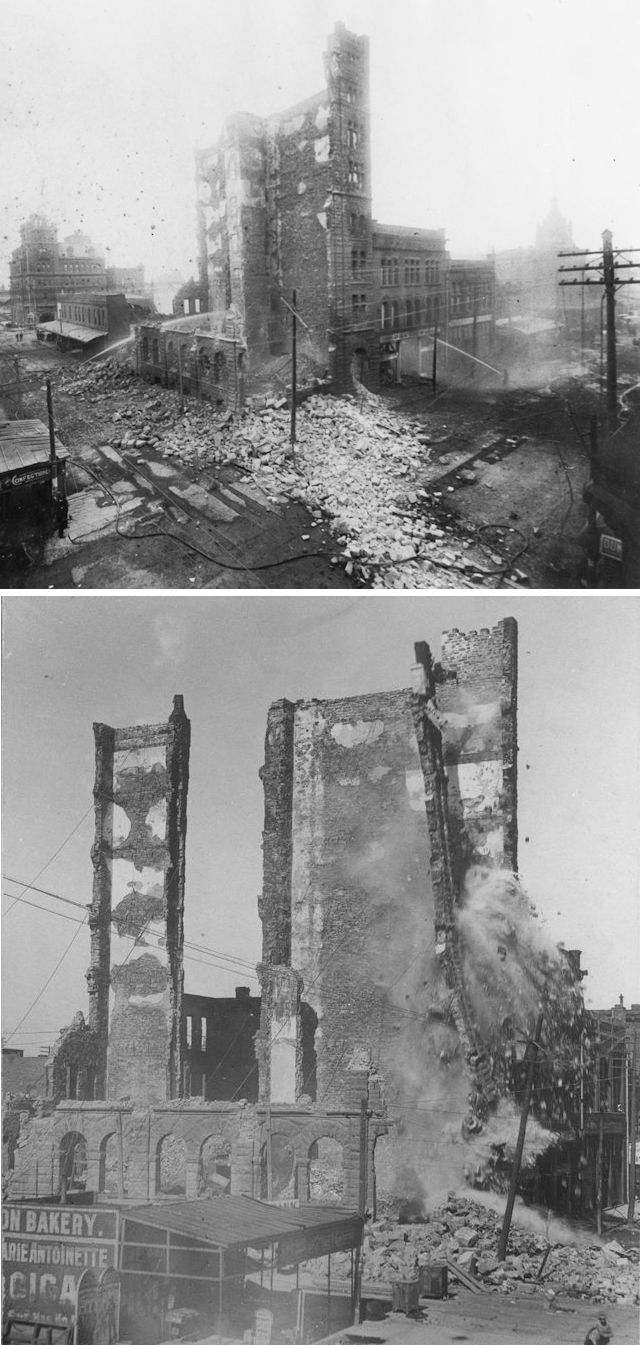

In 1898 the Hurley Building was destroyed in what the Houston Daily Post called “the most disastrous fire in the history of Fort Worth.” To the left in the top photo is the Board of Trade building; to the right is the courthouse. (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In 1898 the Hurley Building was destroyed in what the Houston Daily Post called “the most disastrous fire in the history of Fort Worth.” To the left in the top photo is the Board of Trade building; to the right is the courthouse. (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

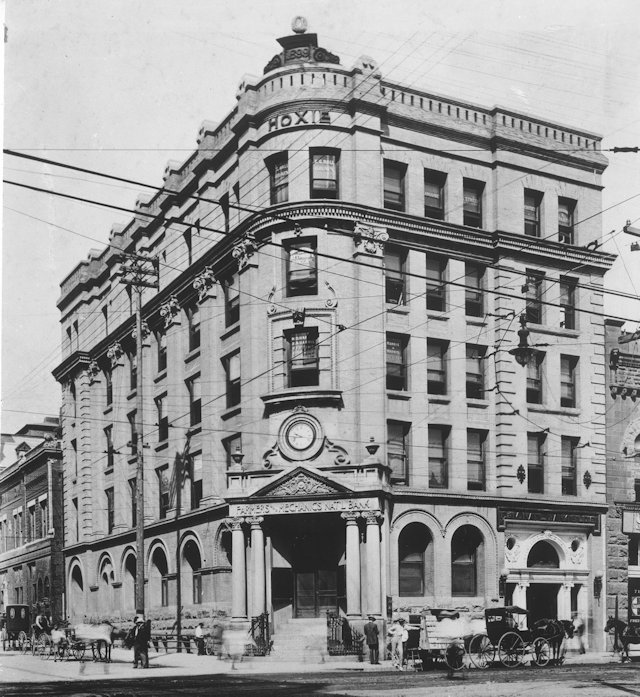

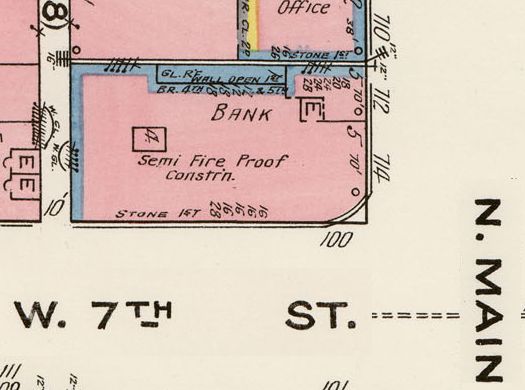

In 1899 a second Hoxie Building, designed by Marshall Sanguinet, was built on the site of the Hurley Building and became the third home of Farmers and Mechanics National Bank. This five-story building was built for John Hoxie’s widow, Mrs. Mary J. Hoxie. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

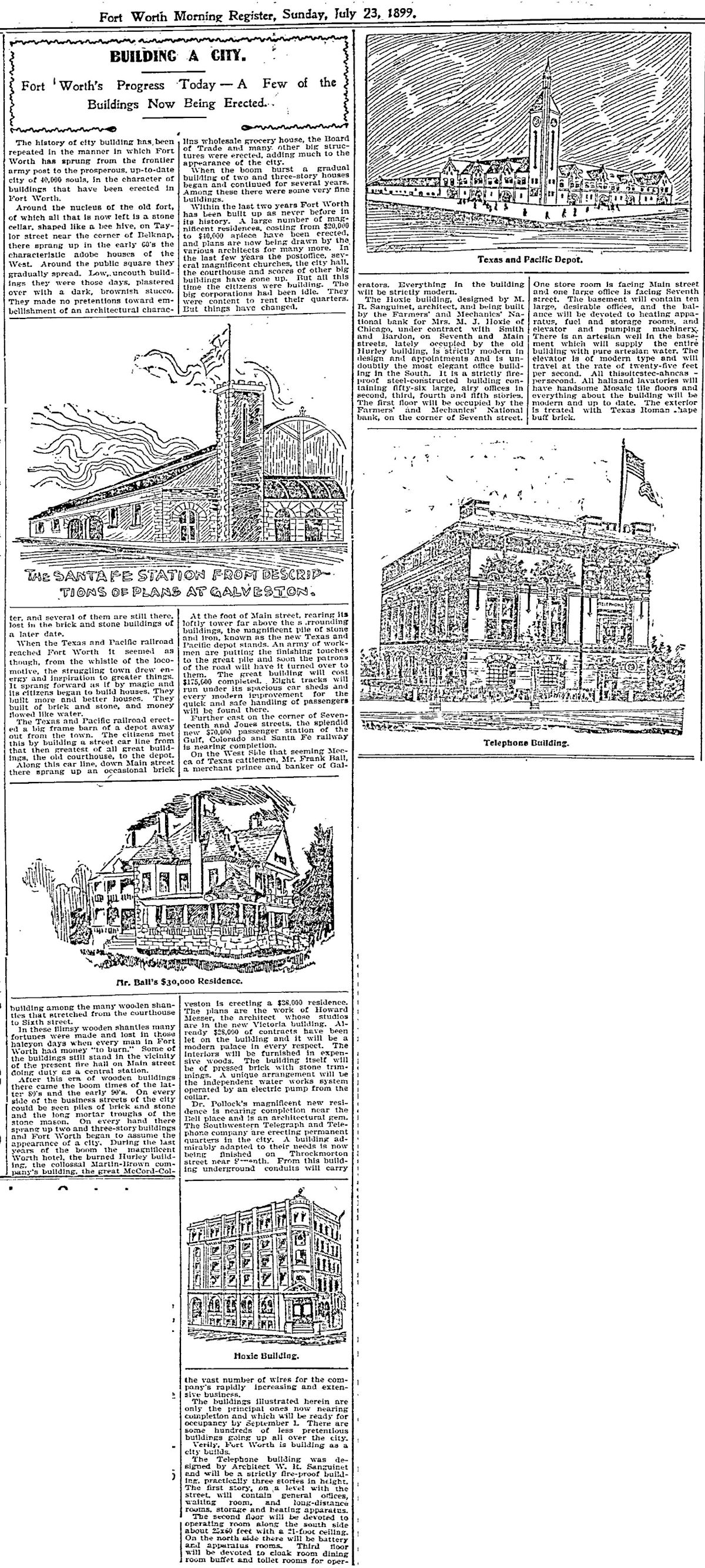

In 1899 Fort Worth was again booming. John Hoxie’s new building was featured in a Fort Worth Register roundup of current construction in town, including the telephone exchange building, Ball-Eddleman-McFarland house, Texas & Pacific passenger depot, and Union Depot.

In 1899 Fort Worth was again booming. John Hoxie’s new building was featured in a Fort Worth Register roundup of current construction in town, including the telephone exchange building, Ball-Eddleman-McFarland house, Texas & Pacific passenger depot, and Union Depot.

At its fourth and last location Farmers and Mechanics National Bank, after absorbing a few other local banks, was itself absorbed by Fort Worth National Bank in 1927. The 1921 building later housed insurance companies before being bought and restored by XTO Energy.

The two locations and four homes of Farmers and Mechanics National Bank.

Below are some current images of the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank Building at 714 Main. The building is now named—wait for it—the “714 Main Building.”

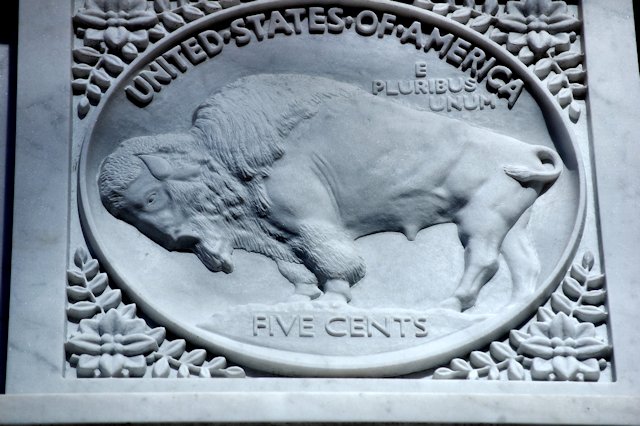

Standing guard in the lobby.

Standing guard in the lobby.

Unfortunately, modern buildings are far less inspired than any of your post’s examples…

Agreed.

Truly inspired. That guy’s heinie is smaller than his cranium.

Thanks, Nancy. Great building, great restoration.