For three-quarters of a century the impact of the bomber plant on Fort Worth’s economy has been substantial. Even more important, the impact of the bomber plant on the balance of war and peace in the world has been substantial.

War has often been an ill wind that has blown good for Fort Worth, beginning in the beginning with the Army’s fort in 1849. Then came Camp Bowie and Camp Taliaferro in 1917.

In 1940, as war raged in Europe, many Americans believed—months before Pearl Harbor—that the United States would be dragged into the seemingly distant war. Among those believers was Amon Carter, Fort Worth’s head cheerleader, back-slapper, and arm-twister. Carter ramrodded a chamber of commerce committee that began lobbying Washington and Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, offering incentives if the government would build Consolidated a military aircraft factory in Cowtown. (All newspaper clips below are from the Star-Telegram and Dallas Morning News; photos of the bomber plant are from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company and Wikipedia.)

But then on December 22, 1940 the Morning News announced that Tulsa, not Fort Worth, would get the prized aircraft plant, which would employ five thousand workers. Jerry Flemmons writes in Amon: The Life of Amon Carter Sr. of Texas: “An apoplectic Amon beat his fists against the wall and exploded by telegram to [President] Roosevelt that Tulsa did not deserve the factory.” Carter stepped up his lobbying for Fort Worth. He slapped backs harder, he twisted arms tighter.

But then on December 22, 1940 the Morning News announced that Tulsa, not Fort Worth, would get the prized aircraft plant, which would employ five thousand workers. Jerry Flemmons writes in Amon: The Life of Amon Carter Sr. of Texas: “An apoplectic Amon beat his fists against the wall and exploded by telegram to [President] Roosevelt that Tulsa did not deserve the factory.” Carter stepped up his lobbying for Fort Worth. He slapped backs harder, he twisted arms tighter.

Six days later the Morning News announced that Tulsa’s celebration had been put on hold. “Groups from Texas personally interposed an objection and demanded that the administration send the plant to Fort Worth.” Few people had the clout and the chutzpah (both of which Amon had by the Stetson hatful) to “demand” of an administration.

Six days later the Morning News announced that Tulsa’s celebration had been put on hold. “Groups from Texas personally interposed an objection and demanded that the administration send the plant to Fort Worth.” Few people had the clout and the chutzpah (both of which Amon had by the Stetson hatful) to “demand” of an administration.

Carter then made a suggestion to FDR: Give both cities an aircraft plant. Three days later, on December 30, the Morning News announced that both cities might indeed get an aircraft plant. (Senator Sheppard was known as “the father of prohibition.”)

Carter then made a suggestion to FDR: Give both cities an aircraft plant. Three days later, on December 30, the Morning News announced that both cities might indeed get an aircraft plant. (Senator Sheppard was known as “the father of prohibition.”)

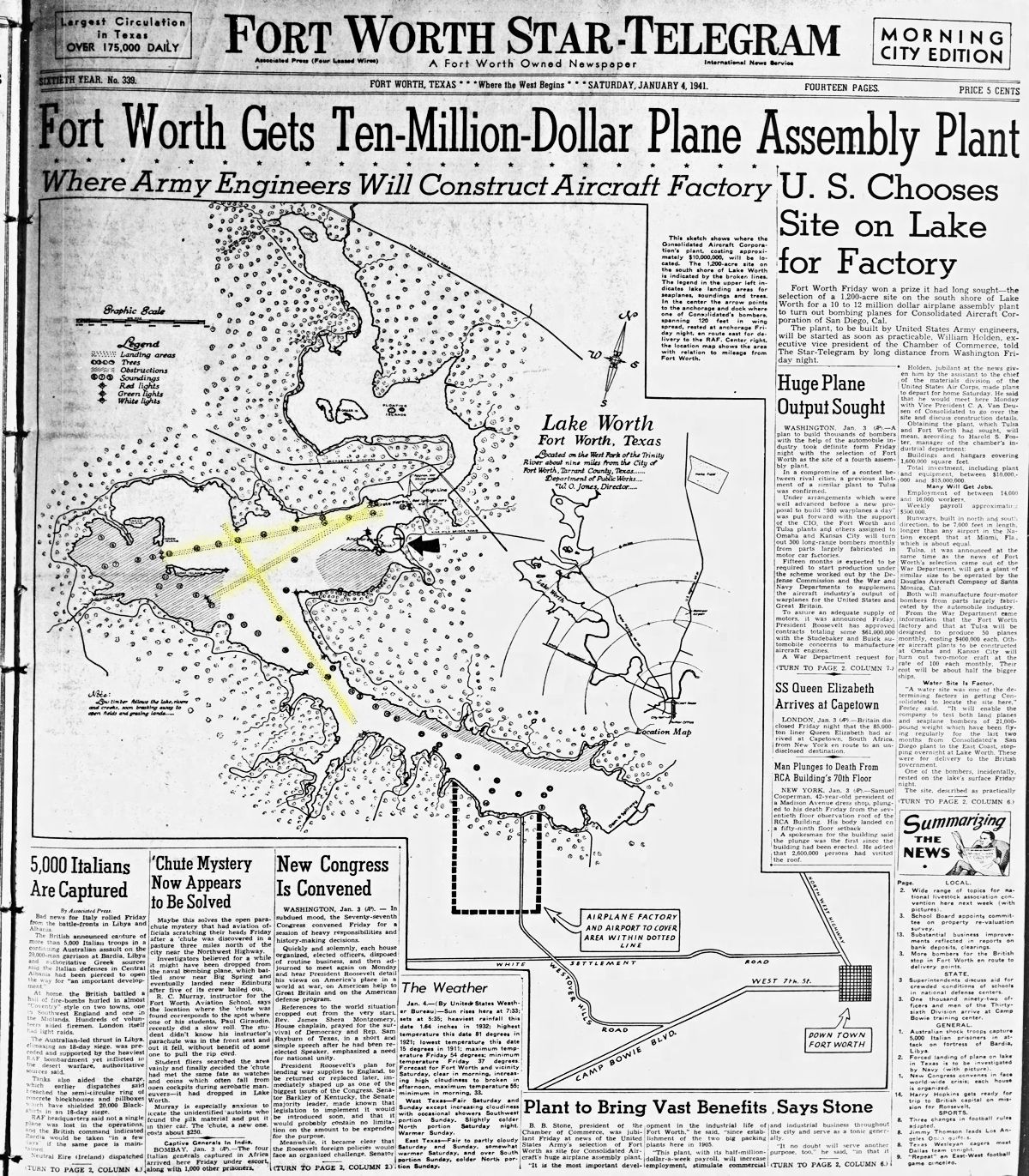

And verily, so it came to pass that on January 4, 1941 the Star-Telegram and Morning News announced that the powers-that-be, with wisdom that was Solomonic if not downright Amonic, had compromised: Both Tulsa and Fort Worth would get $10 million ($162 million today) aircraft plants. The two plants would be identical. The Fort Worth bomber plant would be built on the shore of Lake Worth.

And verily, so it came to pass that on January 4, 1941 the Star-Telegram and Morning News announced that the powers-that-be, with wisdom that was Solomonic if not downright Amonic, had compromised: Both Tulsa and Fort Worth would get $10 million ($162 million today) aircraft plants. The two plants would be identical. The Fort Worth bomber plant would be built on the shore of Lake Worth.

Actually, Amon Carter and Fort Worth already had an “in” with both Consolidated and the federal government. And the choice of Lake Worth as the site for the bomber plant was not random. See those three yellow lines on the map above? Those were landing lanes for seaplanes.

In 1940 Consolidated was building PBY Catalina seaplanes and ferrying them to Britain and Canada, which already were at war. The ferry pilots needed a layover and fueling station midway across the United States. Amon Carter had convinced Consolidated to use Lake Worth. The city provided a seaplane base where the airplanes could land and be serviced. Crews usually overnighted here and departed the next day. This photo shows seaplanes on the lake after being flown up from the gulf to escape a storm.

So. Now that Cowtown was going to get a bomber plant, was Amon Carter satisfied?

What do you think?

Carter wanted the Fort Worth plant to be bigger than the Tulsa plant. Flemmons writes: “Amon demanded a change. Army architects added two more support columns and twenty-nine feet to appease the publisher. Fort Worth had the world’s largest aircraft factory.”

Now Amon was satisfied.

The plant, on twelve hundred acres at Lake Worth, would employ fourteen thousand workers, turn out fifty bombers a month. The plant, civic leaders crowed, would attract other industries, create the need for more housing.

The plant, on twelve hundred acres at Lake Worth, would employ fourteen thousand workers, turn out fifty bombers a month. The plant, civic leaders crowed, would attract other industries, create the need for more housing.

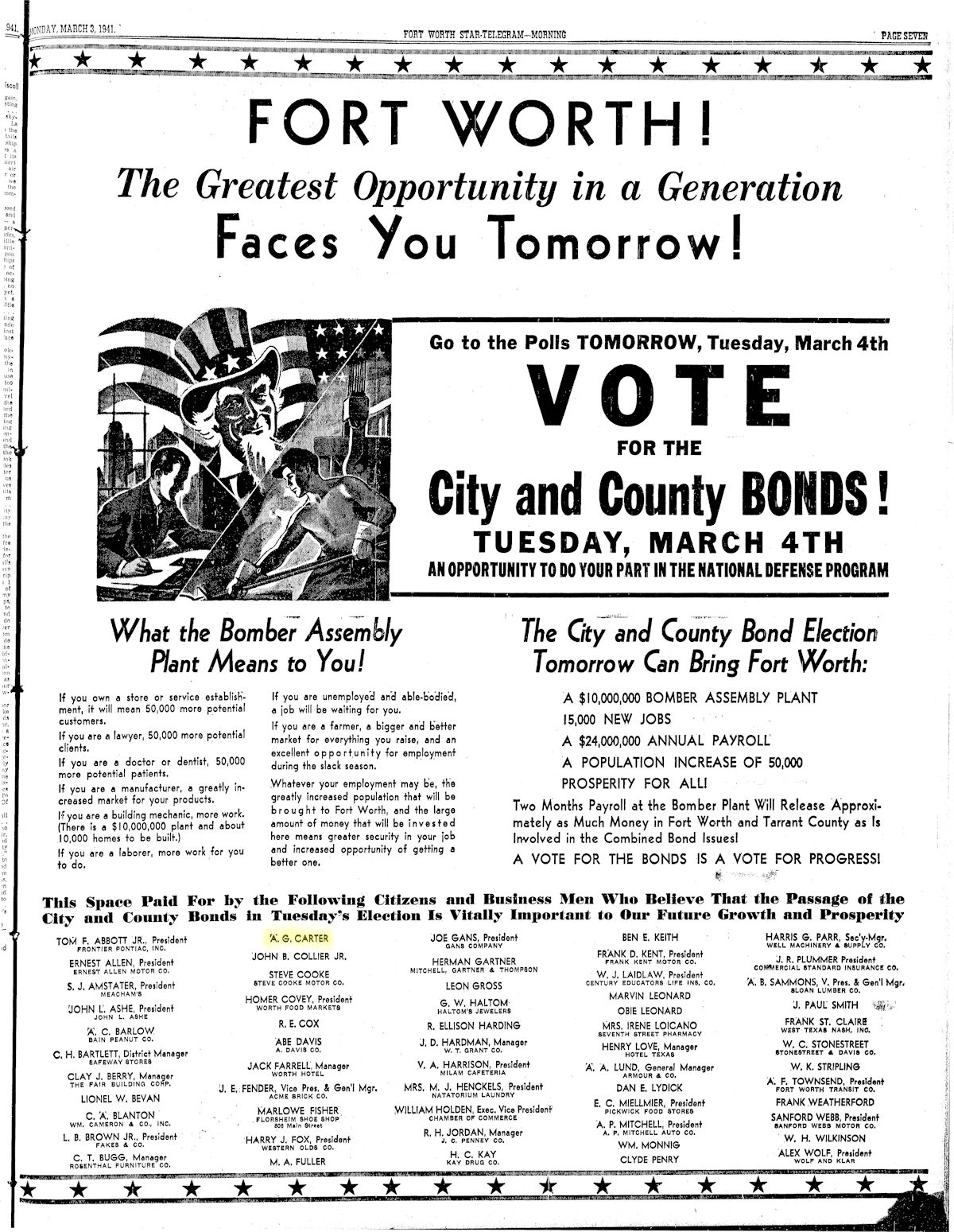

In March Fort Worth voters pitched in, approving a $1.25 million ($21.5 million today) bond package promoted by Amon Carter and other civic leaders to buy the land for the bomber plant and adjacent airfield.

In March Fort Worth voters pitched in, approving a $1.25 million ($21.5 million today) bond package promoted by Amon Carter and other civic leaders to buy the land for the bomber plant and adjacent airfield.

With the bomber plant secured, Fort Worth planned to develop, with federal aid, an “airport and testing field” adjacent to the bomber plant. The Army Air Corps announced that it would assign a heavy bombardment group to the airfield.

With the bomber plant secured, Fort Worth planned to develop, with federal aid, an “airport and testing field” adjacent to the bomber plant. The Army Air Corps announced that it would assign a heavy bombardment group to the airfield.

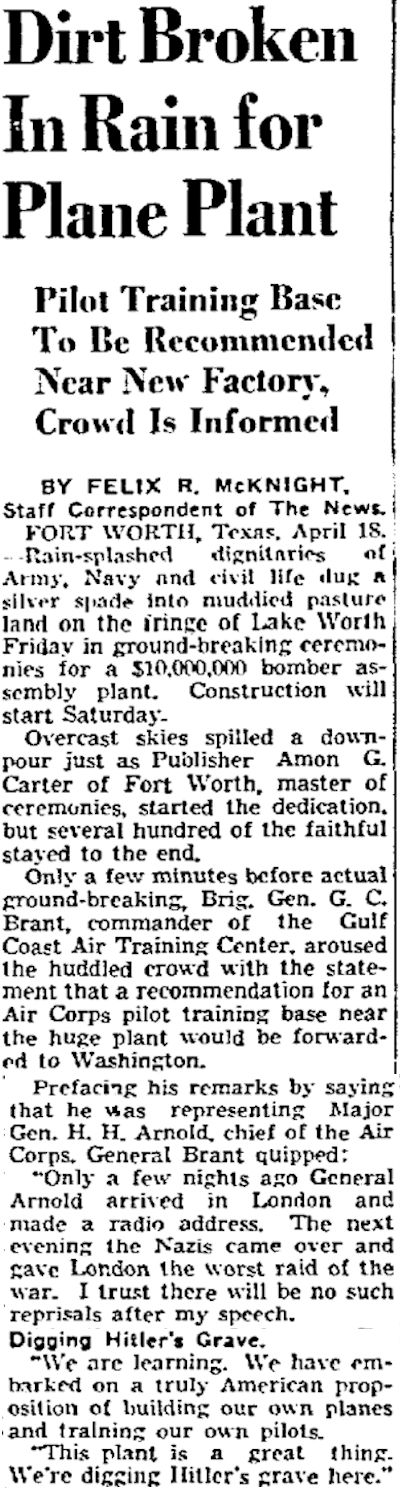

The groundbreaking ceremony for the bomber plant was held on April 18, 1941. Master of ceremonies? Amon himself. Brigadier General G. C. Brant said, “This plant is a great thing. We’re digging Hitler’s grave here.”

The groundbreaking ceremony for the bomber plant was held on April 18, 1941. Master of ceremonies? Amon himself. Brigadier General G. C. Brant said, “This plant is a great thing. We’re digging Hitler’s grave here.”

Amon Carter and General Brant jointly manned the silver spade to turn some dirt for the groundbreaking of the plant.

Amon Carter and General Brant jointly manned the silver spade to turn some dirt for the groundbreaking of the plant.

In June 1941 a railroad spur track was laid from the main Texas & Pacific track in southwest Fort Worth five miles north to the bomber plant site. The “bomber spur” was used to deliver on rail cars, first, steel and other building materials to construct the bomber plant, second, parts to build the bombers, and, third, fuel for the bombers built at the plant and flown from the adjacent airfield.

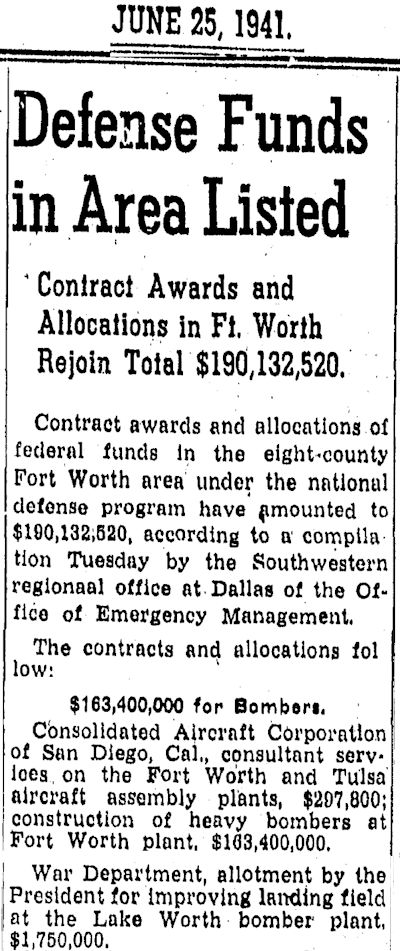

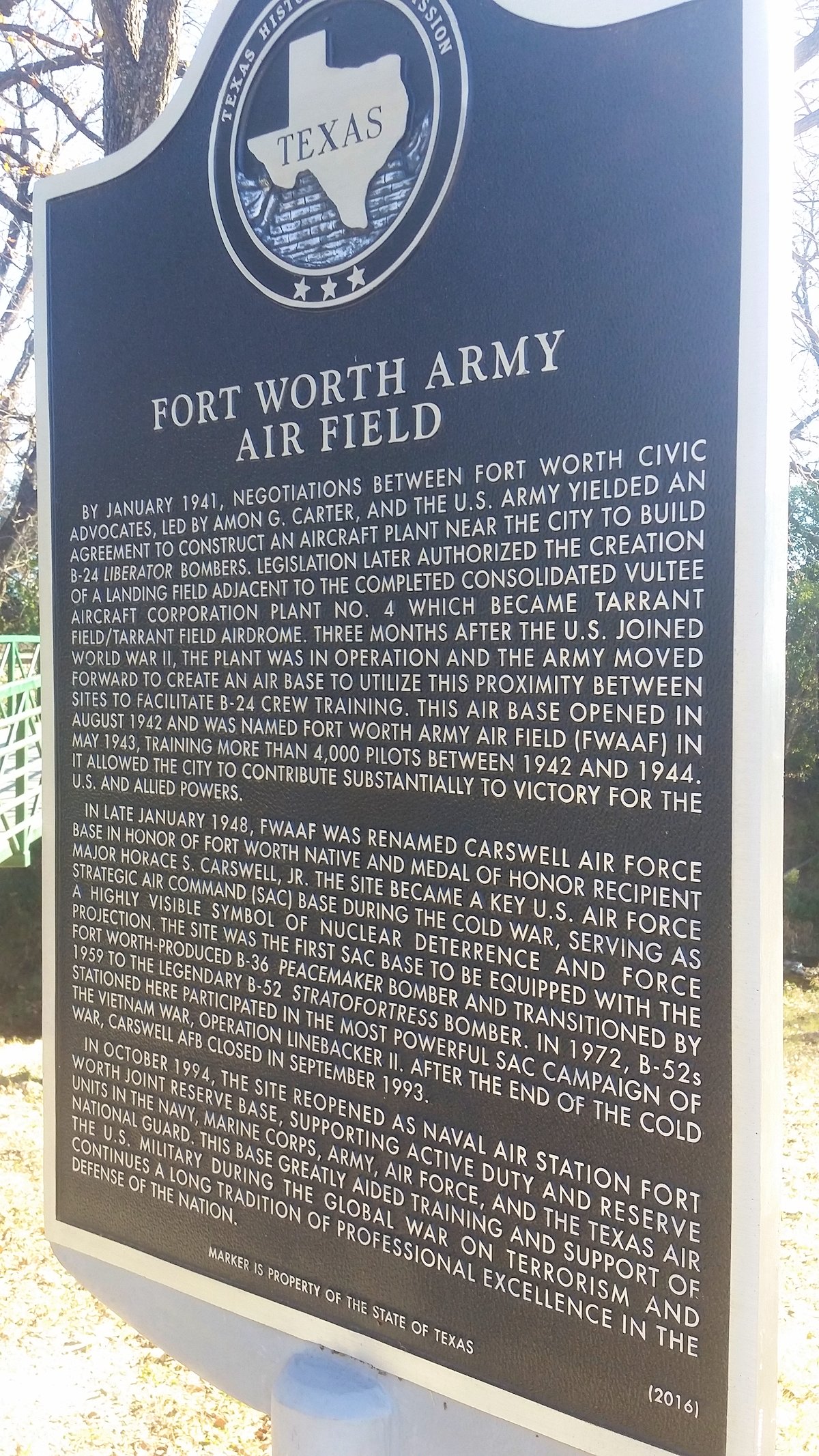

And soon there was more good news: In June President Roosevelt approved $1.75 million to help fund the Lake Worth airfield, initially named “Tarrant Field.” On July 29 the base was renamed “Fort Worth Army Air Field” (later “Carswell Air Force Base”).

And soon there was more good news: In June President Roosevelt approved $1.75 million to help fund the Lake Worth airfield, initially named “Tarrant Field.” On July 29 the base was renamed “Fort Worth Army Air Field” (later “Carswell Air Force Base”).

This marker is at Airfield Falls near the air base.

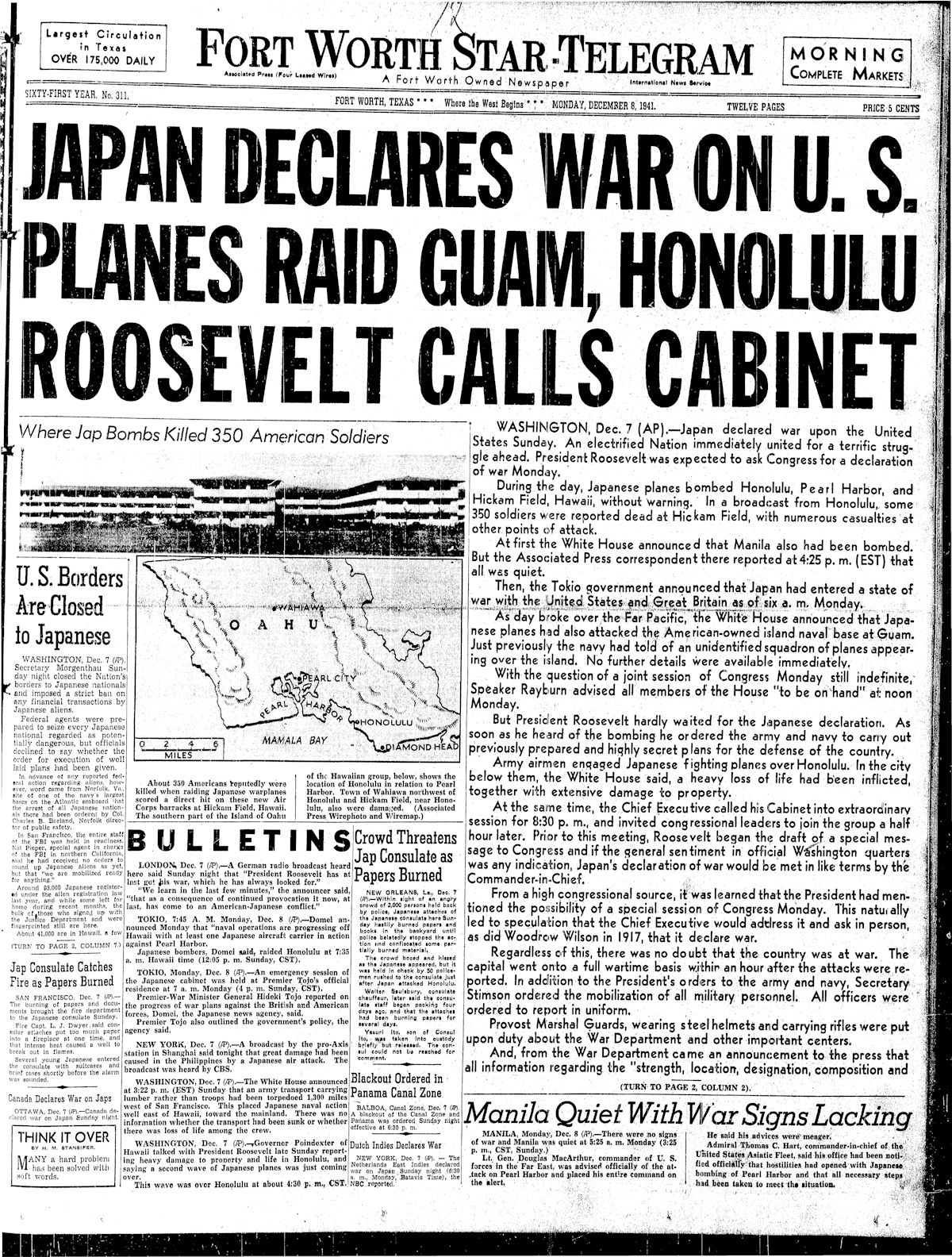

Then came December 7. Remember that this flurry of activity to build bomber plants and airfields had taken place during peacetime. Imagine the urgency now that America was at war!

Then came December 7. Remember that this flurry of activity to build bomber plants and airfields had taken place during peacetime. Imagine the urgency now that America was at war!

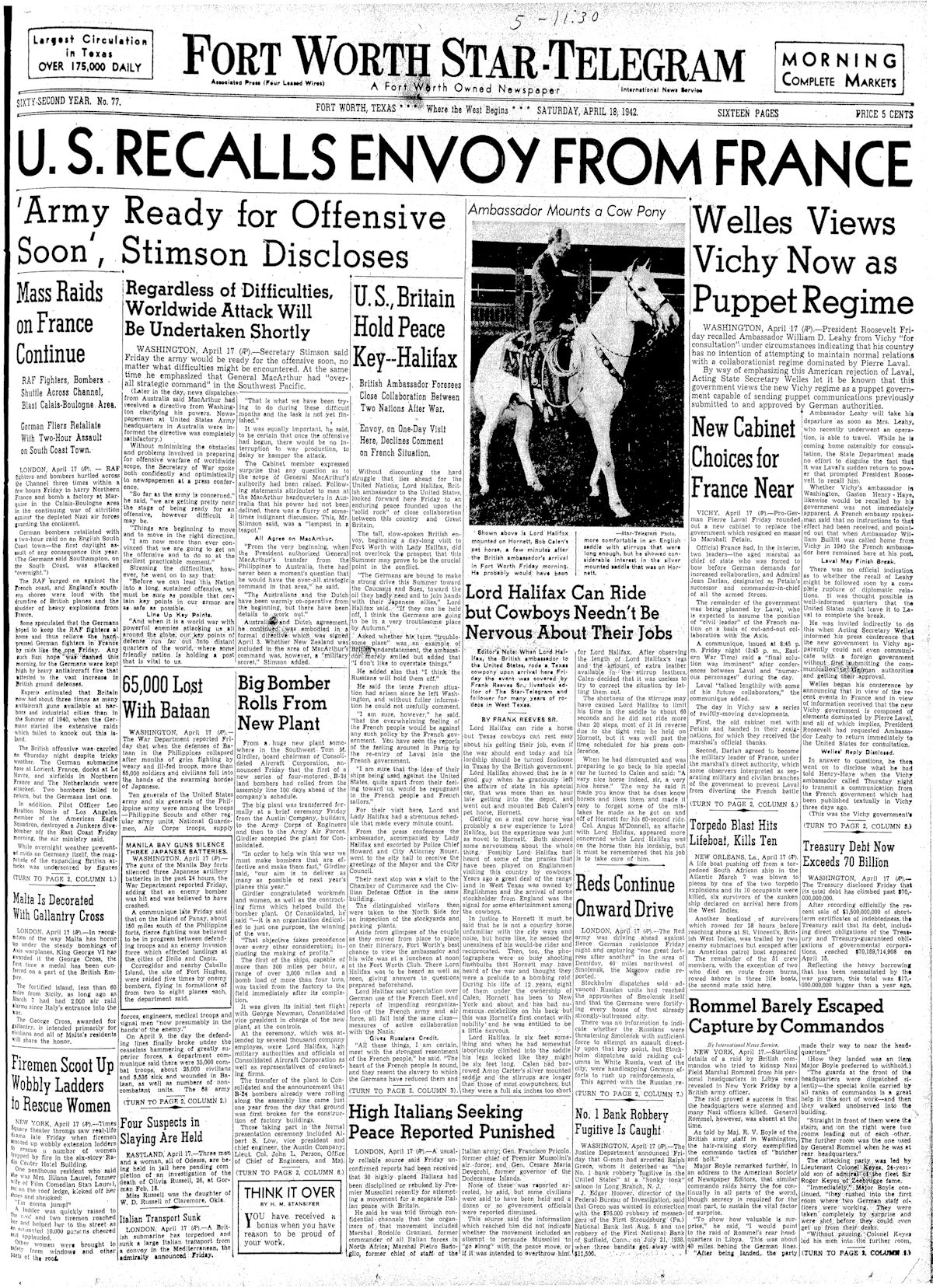

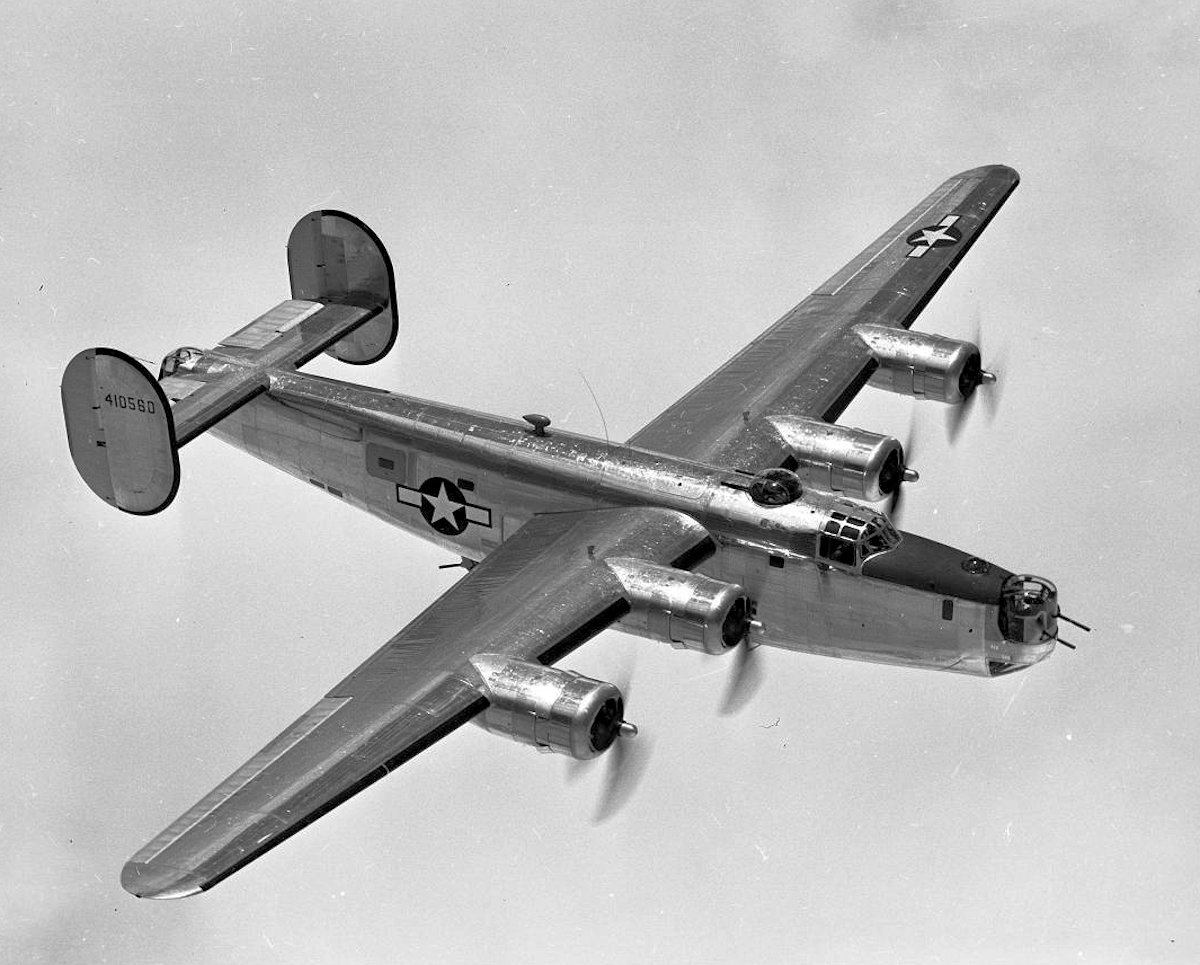

Fast-forward to April 17, 1942. The (almost) mile-long assembly line of Fort Worth’s bomber plant turned out the first of its three thousand B-24s—one hundred days ahead of schedule.

Fast-forward to April 17, 1942. The (almost) mile-long assembly line of Fort Worth’s bomber plant turned out the first of its three thousand B-24s—one hundred days ahead of schedule.

Both newspapers used a vague dateline for the sake of national security: “Somewhere in the Southwest.”

Both newspapers used a vague dateline for the sake of national security: “Somewhere in the Southwest.”

With completion of that first bomber, the bomber plant, too, was declared completed—and two months early. The Star-Telegram published a commemorative edition “with the sanction of the War Department.” As U.S. bombers for the first time bombed the “great cities of Japan,” the newspaper wrote that the construction company that built the plant officially turned it over to the Army Corps of Engineers, which turned it over to the War Department, which turned it over to the Army Air Corps, which turned it over to Consolidated Aircraft Corporation. The Star-Telegram, again being geographically vague, wrote: “Southwest-assembled long-range bombers start rolling, may turn tide of war.”

With completion of that first bomber, the bomber plant, too, was declared completed—and two months early. The Star-Telegram published a commemorative edition “with the sanction of the War Department.” As U.S. bombers for the first time bombed the “great cities of Japan,” the newspaper wrote that the construction company that built the plant officially turned it over to the Army Corps of Engineers, which turned it over to the War Department, which turned it over to the Army Air Corps, which turned it over to Consolidated Aircraft Corporation. The Star-Telegram, again being geographically vague, wrote: “Southwest-assembled long-range bombers start rolling, may turn tide of war.”

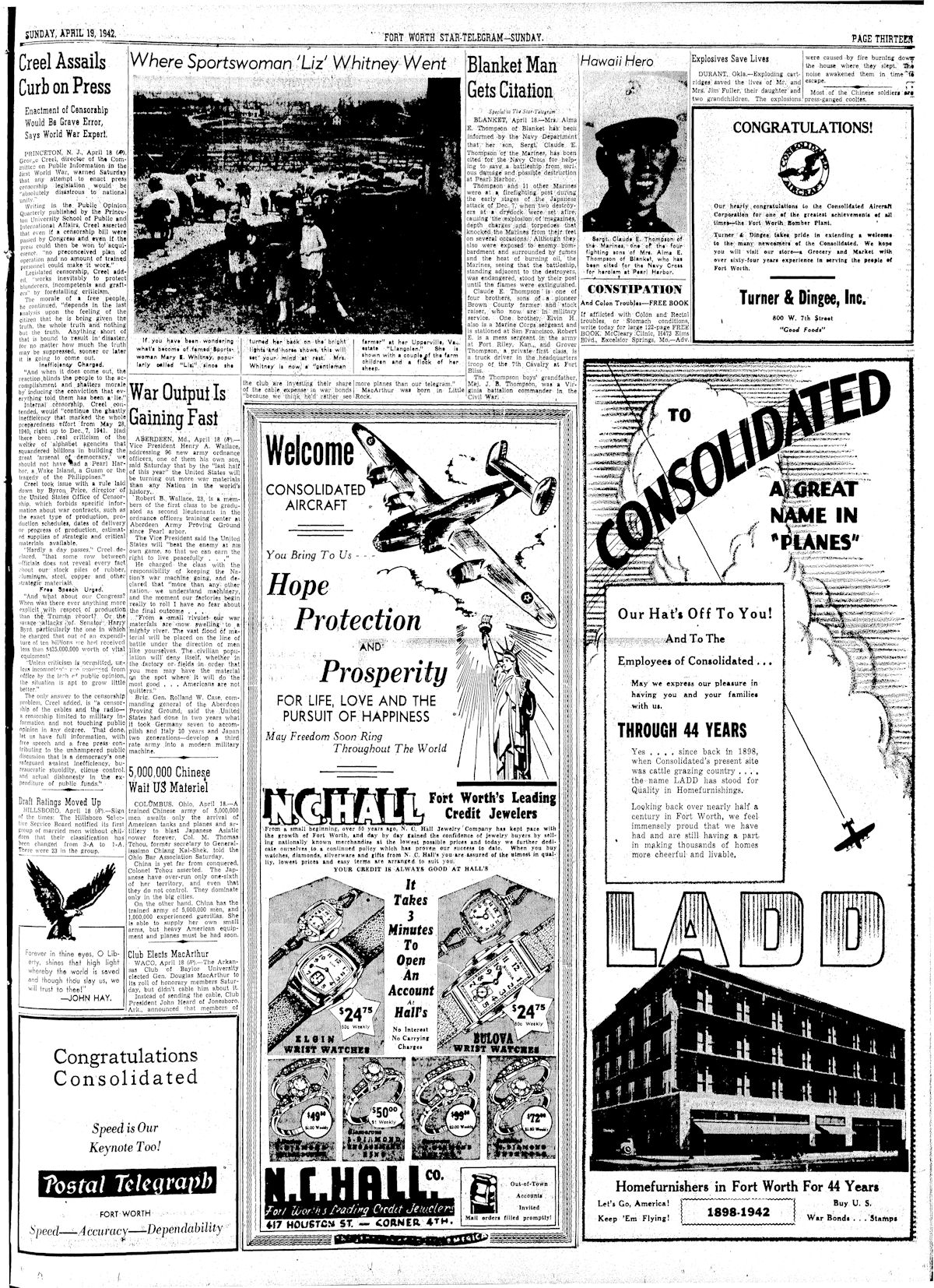

That commemorative edition of the Star-Telegram was filled with ads by local businesses congratulating Consolidated.

That commemorative edition of the Star-Telegram was filled with ads by local businesses congratulating Consolidated.

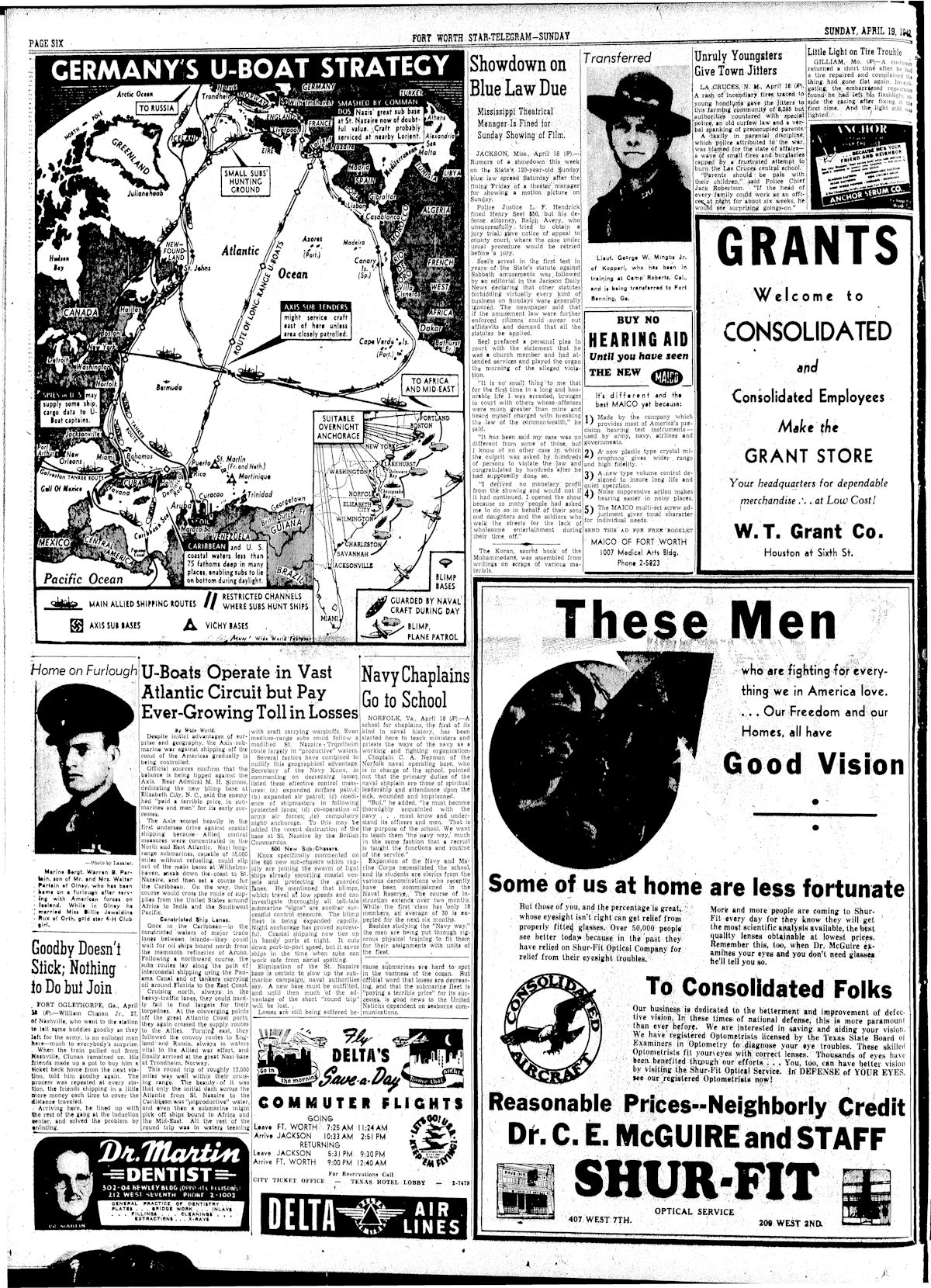

North American Aviation, a division of General Motors, in 1941 built an aircraft plant in Dallas. The plant turned out T-6 trainers and P-51 fighters.

North American Aviation, a division of General Motors, in 1941 built an aircraft plant in Dallas. The plant turned out T-6 trainers and P-51 fighters.

On November 1, 1942 the Morning News printed a big spread about the Fort Worth bomber plant. The plant also produced a cargo version of the B-24 Liberator—the C-87 Liberator Express.

On November 1, 1942 the Morning News printed a big spread about the Fort Worth bomber plant. The plant also produced a cargo version of the B-24 Liberator—the C-87 Liberator Express.

To satisfy the blackout conditions necessary for wartime, the Morning News report said, Fort Worth’s bomber plant had no windows. Thus, the plant needed a lot of lights (its fluorescent light tubes could stretch from Fort Worth to Dallas) and air conditioning (fourteen thousand gallons of water a minute were pumped from Lake Worth to run the refrigeration system, which had a cooling capacity equal to five hundred thousand home refrigerators).

To satisfy the blackout conditions necessary for wartime, the Morning News report said, Fort Worth’s bomber plant had no windows. Thus, the plant needed a lot of lights (its fluorescent light tubes could stretch from Fort Worth to Dallas) and air conditioning (fourteen thousand gallons of water a minute were pumped from Lake Worth to run the refrigeration system, which had a cooling capacity equal to five hundred thousand home refrigerators).

The plant’s monthly electric bill was $20,000 ($282,000 today).

A B-24, the report further noted, contained 957,000 rivets, 4,100 feet of hydraulic, gasoline, oil, and air lines, 34,700 feet of electric wire, and 19,100 nuts, bolts, screws, and washers. But who’s counting?

Three shifts worked around the clock at the plant. Twenty-three percent of the workers in 1942 were women; 51 percent of the workers were graduates of a Texas vocational war industry training school. The Morning News report said midgets were employed to buck rivets in tight spaces.

Three shifts worked around the clock at the plant. Twenty-three percent of the workers in 1942 were women; 51 percent of the workers were graduates of a Texas vocational war industry training school. The Morning News report said midgets were employed to buck rivets in tight spaces.

To house all those aircraft workers, in 1942 the government had quickly erected a housing area south of the bomber plant. The area was named “Liberator Village” after the B-24. Liberator Village became part of White Settlement in 1954 and closed the next year.

To house all those aircraft workers, in 1942 the government had quickly erected a housing area south of the bomber plant. The area was named “Liberator Village” after the B-24. Liberator Village became part of White Settlement in 1954 and closed the next year.

On April 20, 1943 the Morning News reported that Undersecretary of War Patterson congratulated the bomber plant workers on their first year of production. (WAAC was Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.)

On April 20, 1943 the Morning News reported that Undersecretary of War Patterson congratulated the bomber plant workers on their first year of production. (WAAC was Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.)

When the war had begun, Fort Worth had 176,000 people; Tarrant County had 225,000. During the plant’s peak in 1944-1945, according to the Texas State Historical Association, the plant employed thirty-eight thousand workers. That’s one in five Fort Worth residents, one in six county residents. Probably most residential blocks in Fort Worth had at least one resident who worked at the bomber plant.

Consolidated produced a version of the B-24 for the Navy.

Consolidated produced a version of the B-24 for the Navy.

Amon Carter with a B-24 named City of Fort Worth.

Amon Carter with a B-24 named City of Fort Worth.

Inevitably there was tragedy, certainly as men flew B-24s into combat and even as they flew B-24s in training from the Army airfield. On September 4, 1943 on a front page filled with news of a war being fought overseas, the headline “Seven Killed When Two Bombers Collide Near Here” brought the war close to home: Two B-24s flying from the Fort Worth airfield had collided over Birdville, killing both crews.

Inevitably there was tragedy, certainly as men flew B-24s into combat and even as they flew B-24s in training from the Army airfield. On September 4, 1943 on a front page filled with news of a war being fought overseas, the headline “Seven Killed When Two Bombers Collide Near Here” brought the war close to home: Two B-24s flying from the Fort Worth airfield had collided over Birdville, killing both crews.

The next year, on March 27, 1944, the Morning News reported that four airmen had been killed when a B-24 overshot Fort Worth Army Air Field and crashed on a training flight.

The next year, on March 27, 1944, the Morning News reported that four airmen had been killed when a B-24 overshot Fort Worth Army Air Field and crashed on a training flight.

The bomber plant produced the B-24 Liberator for two years. Then it produced the less-iconic B-32 Dominator (pictured) beginning in 1944.

The bomber plant produced the B-24 Liberator for two years. Then it produced the less-iconic B-32 Dominator (pictured) beginning in 1944.

After the B-24 and B-32 the world’s biggest aircraft plant built the world’s biggest bomber: the behemoth (230-foot wingspan) B-36 Peacemaker beginning in 1946.

After the B-24 and B-32 the world’s biggest aircraft plant built the world’s biggest bomber: the behemoth (230-foot wingspan) B-36 Peacemaker beginning in 1946.

Just as there was a B-24 City of Fort Worth, there was a B-36 City of Fort Worth. It was the first combat-model B-36. In June 1948 it was taxied from the bomber plant to Carswell and delivered to the Air Force.

Just as with the B-24, there was tragedy with the B-36. On September 16, 1949 the Morning News reported that a B-36 had crashed into Lake Worth. Five airmen were killed.

Just as with the B-24, there was tragedy with the B-36. On September 16, 1949 the Morning News reported that a B-36 had crashed into Lake Worth. Five airmen were killed.

The 1955 movie Strategic Air Command starring Jimmy Stewart was filmed in part at Carswell. In the control tower scene the bomber plant’s assembly building can be seen in the background and B-36s in the middle ground. In the bottom scene Stewart is walking with actor Harry Morgan alongside B-36 s/n 5734. Fame is fleeting: In 1957 B-36 s/n 5734 was scrapped.

After the B-36, the bomber plant produced the delta-winged B-58 Hustler in the late 1950s.

After the B-36, the bomber plant produced the delta-winged B-58 Hustler in the late 1950s.

A Hustler with its big uncle Peacemaker.

A Hustler with its big uncle Peacemaker.

Two Cowtown icons: the B-58 Hustler and Reddy Kilowatt.

Two Cowtown icons: the B-58 Hustler and Reddy Kilowatt.

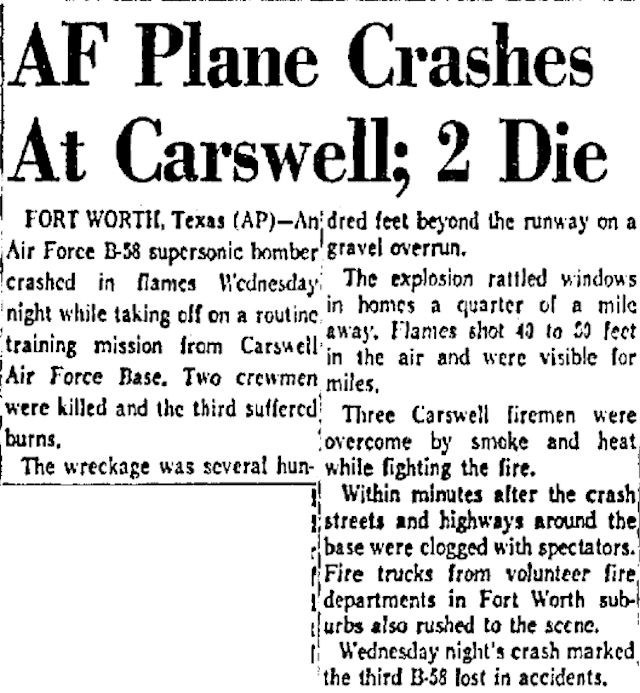

Again, the Grim Reaper occasionally was the co-pilot of the bomber plant’s warplanes. On September 17, 1959 the Morning News reported that two airmen were killed when a B-58 crashed on a training flight in Fort Worth.

Again, the Grim Reaper occasionally was the co-pilot of the bomber plant’s warplanes. On September 17, 1959 the Morning News reported that two airmen were killed when a B-58 crashed on a training flight in Fort Worth.

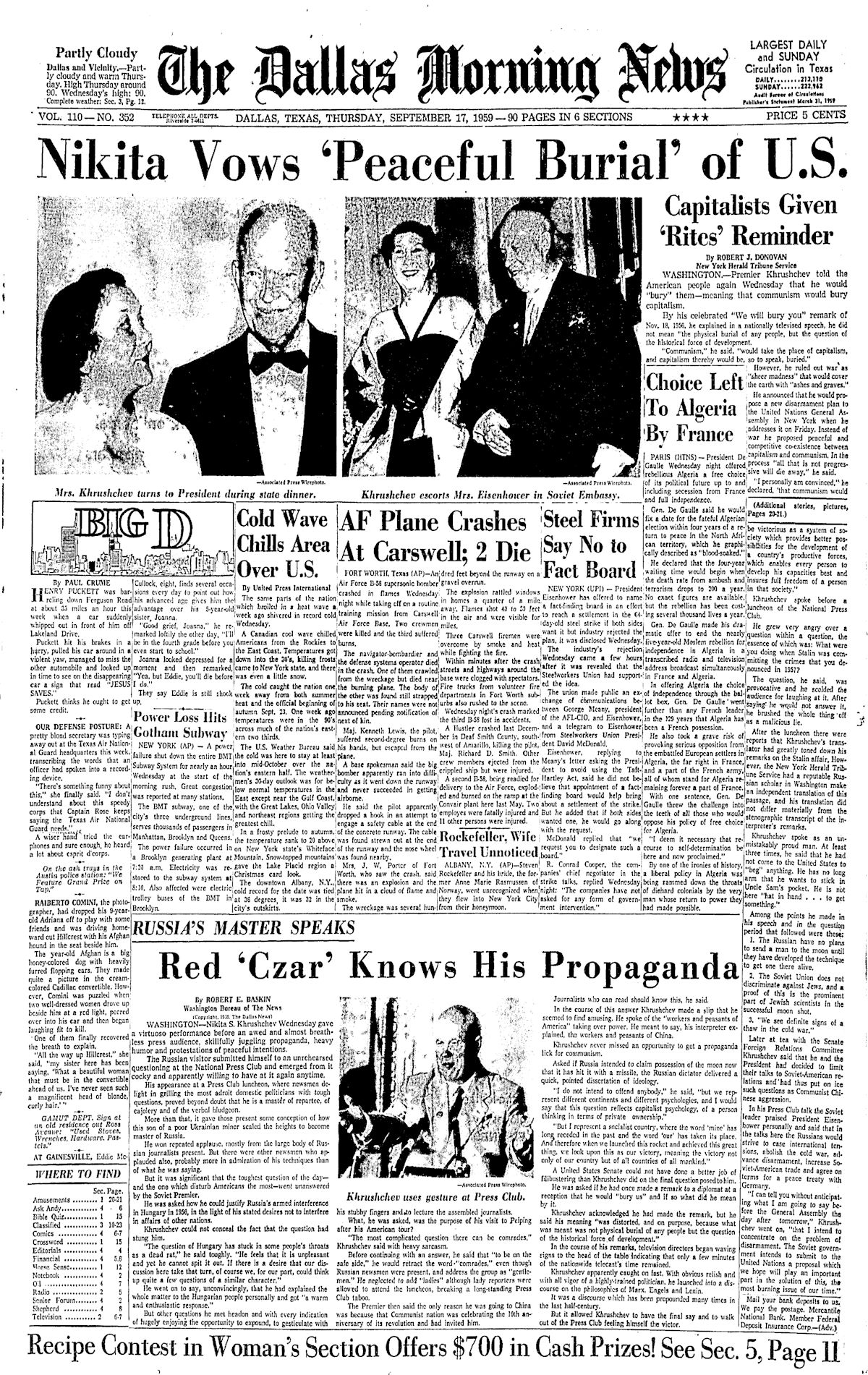

The B-58 crash shared the front page with the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev, who had repeated his 1956 vow to “bury” the United States.

The B-58 crash shared the front page with the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev, who had repeated his 1956 vow to “bury” the United States.

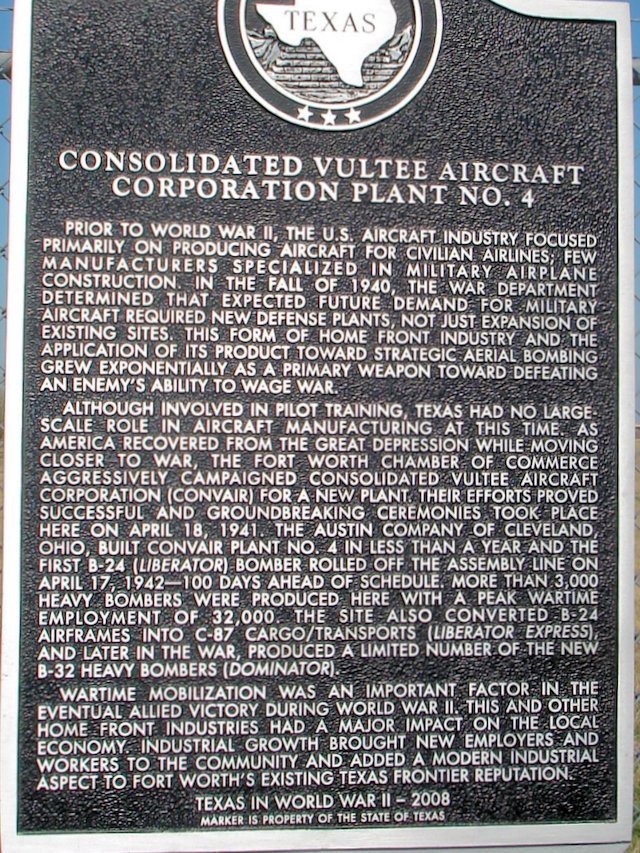

The U.S. government’s bomber plant officially is “Air Force Plant 4.” (There have been more than eighty Air Force plants. AFP 1 was Glenn L. Martin Bomber Plant near Omaha, Nebraska; AFP 2 was North American Aviation’s plant near Kansas City, Kansas; AFP 3 was the Douglas Aircraft Company plant at Tulsa.) Air Force Plant 4 has had several corporate occupants in its three-quarters of a century. In 1943 Consolidated Aircraft Corporation merged with Vultee Aircraft to form Consolidated Vultee Aircraft (Convair). In 1953 General Dynamics purchased Convair and took over the plant. In 1993 Lockheed bought GD’s Fort Worth division. In 1995 Lockheed became Lockheed Martin. Today the plant employs seventeen thousand people.

The bomber plant today. By whatever name you call it, it goes back to 1941, when Amon Carter slapped backs, twisted arms, and with a silver spade turned dirt for the bomber plant and Hitler’s grave.

My mother worked there building the B-24 in the 1940s, my father worked at Carswell in the 1970s, my brother helped build F-16s there in the 90s, and my nephew has helped study and improve the F-35 there for the past decade.

Remember Mrs. Catherine Baker, fourth grade teacher at D.McRae? She scared the Bazooka gum out of me the day after the 1959 crash at Carswell when she told our class that it was caused by sabotage….I expected to have one of those “get out in the hall and cover your neck” air raid drills at any moment….Who expected we would do that in earnest in 1962?

LOL, Dan. I do remember her. She sure gave you kids a head start on Cold War paranoia.

My mother worked at the bomber plant during the war in a tool check-out cage.

Hard to overestimate the economic impact of the bomber plant during that time. Wish I could see time-lapse film of shift-change traffic.

Thanks for this great post. One of my aunts met her future husband when he was stationed at the air field when training as a pilot on B-24s before being sent to England to fly them on bombing runs over Germany. He flew 36 missions and made it home safely. Later, my father (a Navy veteran) worked for several years at “the plant,” which by that time was owned by General Dynamics.

Thanks. A monumental time in the history of both America and England. As a travel writer I toured the remnants of WWII 8th Army airfields in East Anglia and talked to the people, who remembered German doodlebugs falling at night and the sky being filled with departing or returning American bombers during the day. People with metal detectors were still finding war relics in parks and fields a half-century later.

Thanks Hometown!

Do you have or know where to find and photos of the Bill McDavid Pontiac Inc. Dealership at 2917 W. 7th. St. ?

Mr. Vecchio, it’s a long shot, but the photo archives of the Star-Telegram and a few Fort Worth commercial photographers from the past are at UTA Library.

Here’s another one of those “architect Wiley Clarkson had his hands in this also” moments. After the war started, my grandfather, who already had established connections in the government, formed a firm called Clarkson, Pelich, Gerens, and Rady”. He would lead in the firm in the design of numerous large scale projects for the U.S. Engineers. One of those projects was The Liberator Village government housing area for employees of the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation aircraft manufacturing plant. Liberator village was constructed after April of 1942 to house workers who were having a hard time finding housing.

love it !