Today we call them “ghost signs.” But these now-faded signs on the walls of buildings were the latest in outdoor advertising before billboards lined highways and neon flashed over city sidewalks. Artists—called “walldogs”—painted such signs on the exterior walls of businesses to advertise the businesses or national brands. Walldogs made a sketch drawn to scale, mixed their own (lead-based) paints, and free-handed each sign, fitting the layout of the sketch to the wall space available. Walldogs relied on big letters and high-contrast colors to catch the eye of consumers. Brick walls were their preferred canvas: The courses of bricks made a handy grid.

If you know where to look around town, you can still see a few signs that have not given up the ghost, handpainted by, if you will, Norman Rockwalls.

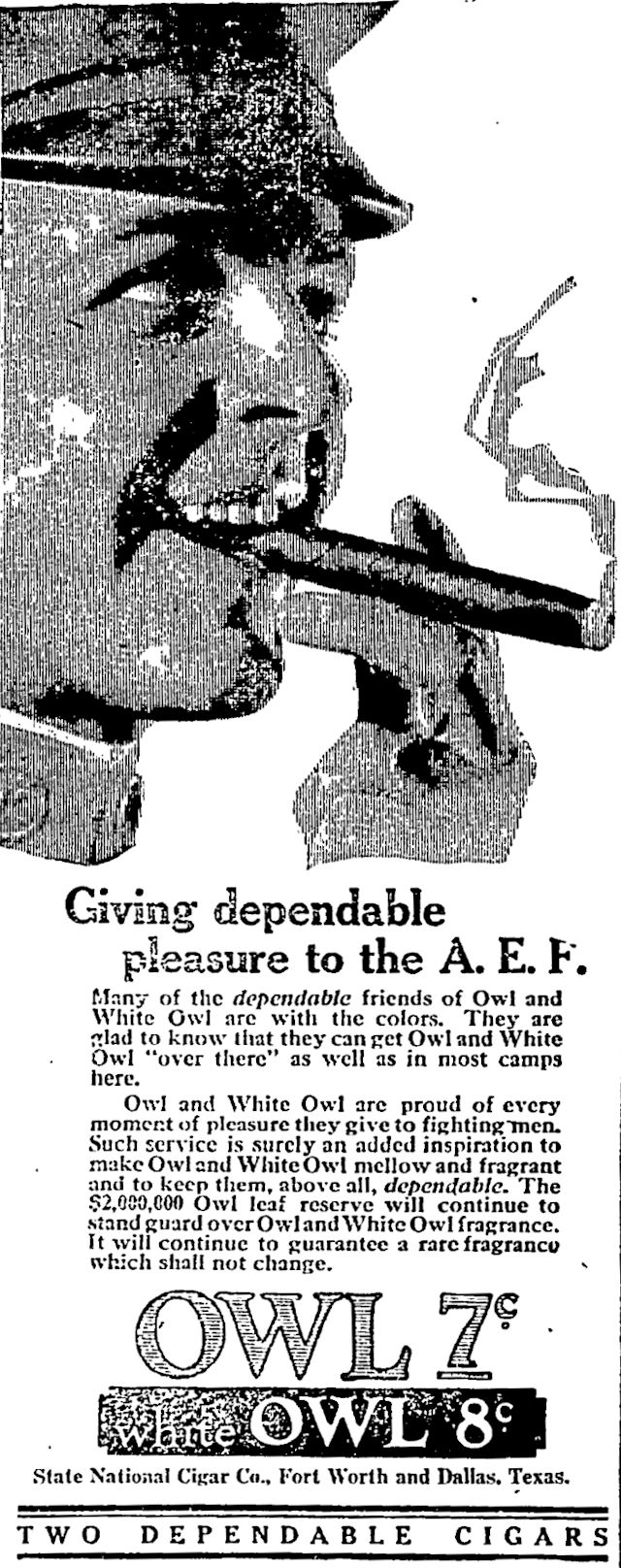

On December 10, 1918, just a month after World War I ended, this ad appeared in the Star-Telegram. Advertisements for Owl and White Owl cigars were common at one time in newspapers and on building walls.

On December 10, 1918, just a month after World War I ended, this ad appeared in the Star-Telegram. Advertisements for Owl and White Owl cigars were common at one time in newspapers and on building walls.

At least three Owl cigars ghost signs survive on the North Side, two of them on one building on West Exchange Avenue.

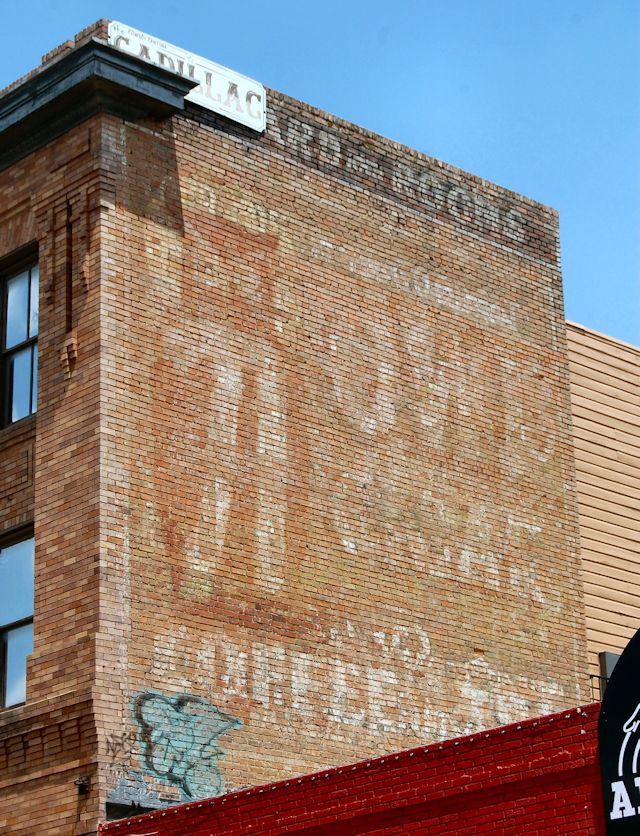

Can you make out the big owl on the left side of the wall, above the letters “COF” in “COFFEE” across the bottom? This ad for Owl brand cigars is on the east wall of the Cantina Cadillac bar building (1908) on Exchange Avenue near the Stockyards. In earlier incarnations the building was a hotel, boarding house, furniture company, dry goods store, and Stockyards Lodge 1224 of the Masons. Owl brand cigars (which became White Owl brand cigars in 1917) were made in New York. The company began in 1861 as Straiton & Storm Company. Why “Owl”? Founder Frederic Storm came up with the Owl brand name one night in 1871 after a white owl flew into a bedroom window of his home on Long Island.

Can you make out the big owl on the left side of the wall, above the letters “COF” in “COFFEE” across the bottom? This ad for Owl brand cigars is on the east wall of the Cantina Cadillac bar building (1908) on Exchange Avenue near the Stockyards. In earlier incarnations the building was a hotel, boarding house, furniture company, dry goods store, and Stockyards Lodge 1224 of the Masons. Owl brand cigars (which became White Owl brand cigars in 1917) were made in New York. The company began in 1861 as Straiton & Storm Company. Why “Owl”? Founder Frederic Storm came up with the Owl brand name one night in 1871 after a white owl flew into a bedroom window of his home on Long Island.

On that same building, can you see the head of the owl posed against a full moon? At the bottom is “now 5 cts.”

On that same building, can you see the head of the owl posed against a full moon? At the bottom is “now 5 cts.”

Part of another Owl cigars sign can barely be made out in the lower-right corner of this much-used wall of the AFL-CIO union hall (1908) on North Main Street. This Owl sign originally read “Straiton & Storm’s Owl Cigar Now 5 Cts.”

Part of another Owl cigars sign can barely be made out in the lower-right corner of this much-used wall of the AFL-CIO union hall (1908) on North Main Street. This Owl sign originally read “Straiton & Storm’s Owl Cigar Now 5 Cts.”

The Stockyards area is the host with the most ghosts. Here are some more:

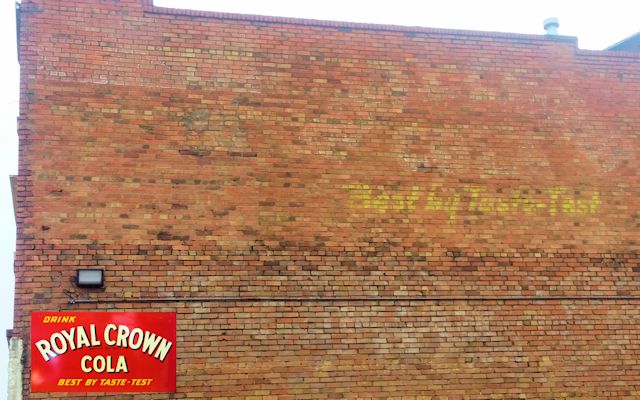

On the north wall of the Lehman Dry Goods Company building (1919) at 2457 North Main is a faded sign for Royal Crown Cola: “best by taste-test.” The wall sign probably looked like the vintage metal sign in the inset.

On the north wall of the Lehman Dry Goods Company building (1919) at 2457 North Main is a faded sign for Royal Crown Cola: “best by taste-test.” The wall sign probably looked like the vintage metal sign in the inset.

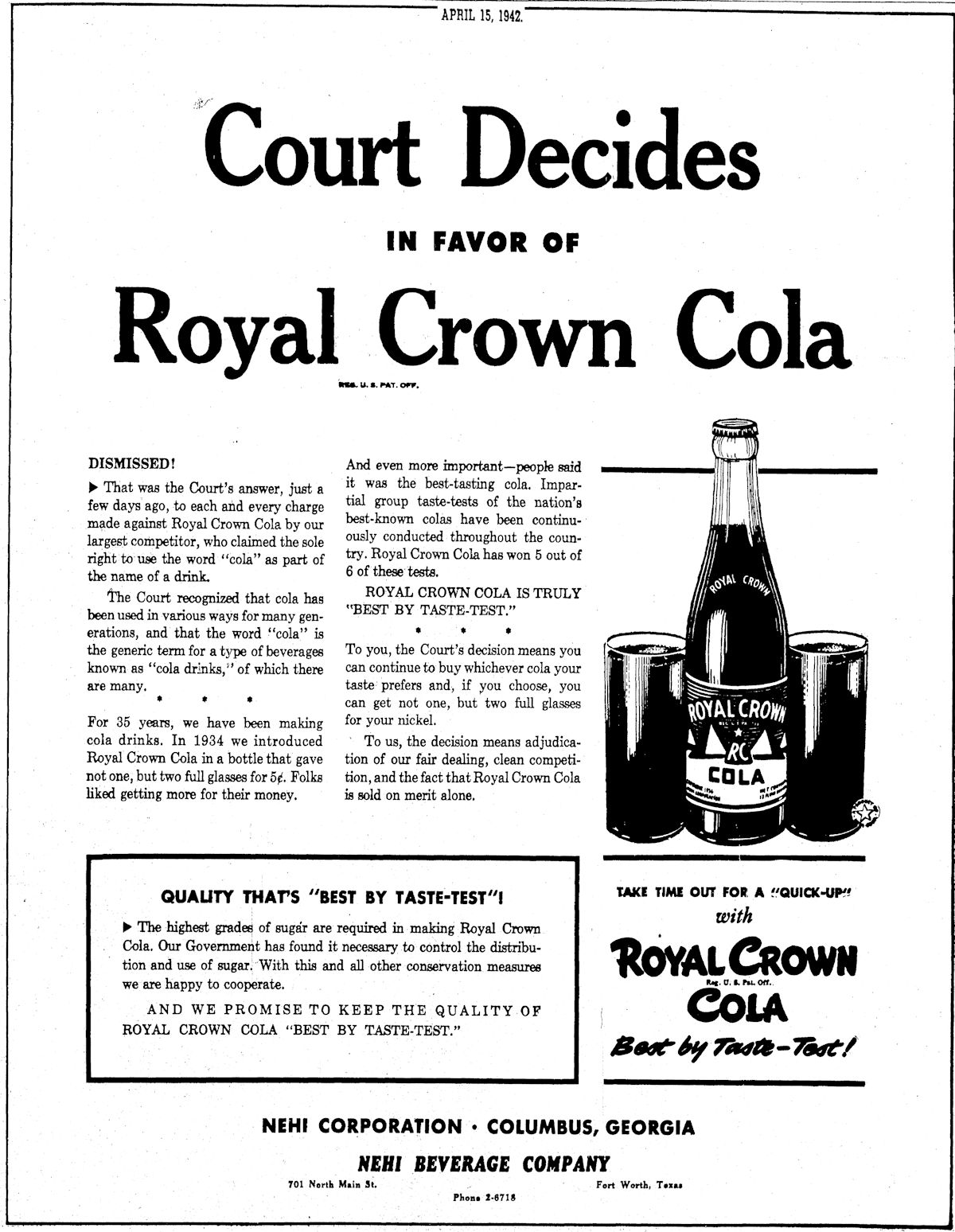

Fort Worth had a Royal Crown bottling plant (Nehi Beverage Company) at 701 North Main. In 1942 Coca-Cola sued Royal Crown over use of the word cola.

Fort Worth had a Royal Crown bottling plant (Nehi Beverage Company) at 701 North Main. In 1942 Coca-Cola sued Royal Crown over use of the word cola.

The Royal Crown bottling plant building still stands.

The Royal Crown bottling plant building still stands.

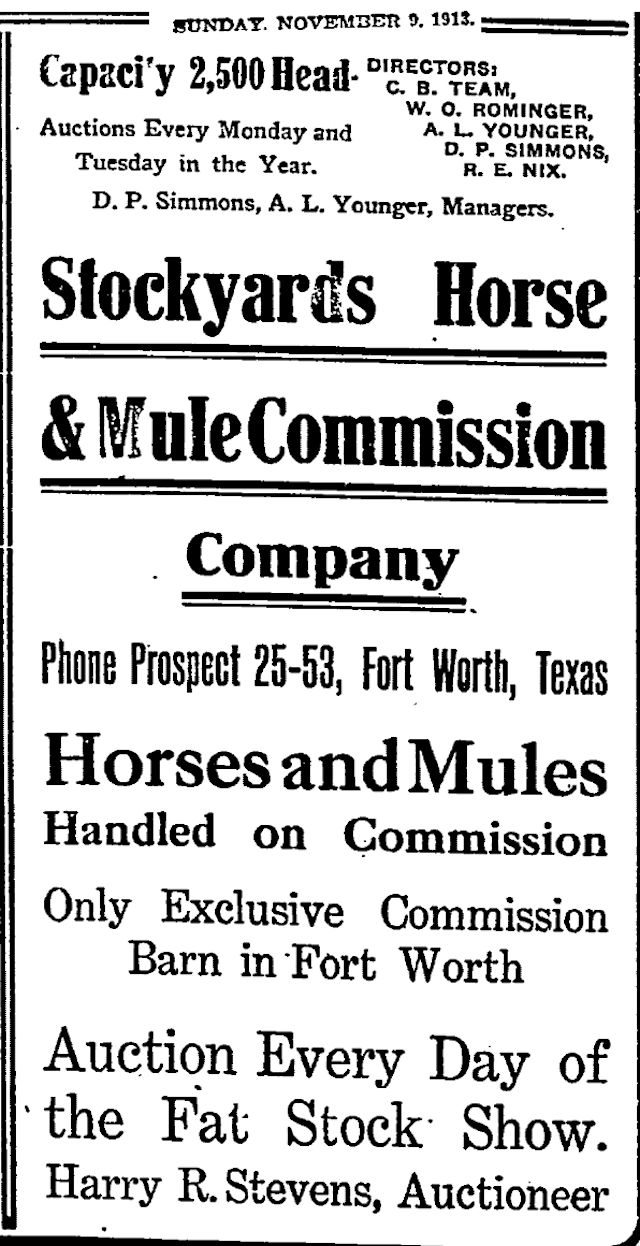

On the Marine Creek side of the horse and mule barns at the Stockyards are two signs:

Partially hidden by a tree at the south end of the building is “Stockyards Horse & Mule Com. Co.”

Partially hidden by a tree at the south end of the building is “Stockyards Horse & Mule Com. Co.”

Note that one of the directors was W. O. Rominger.

Note that one of the directors was W. O. Rominger.

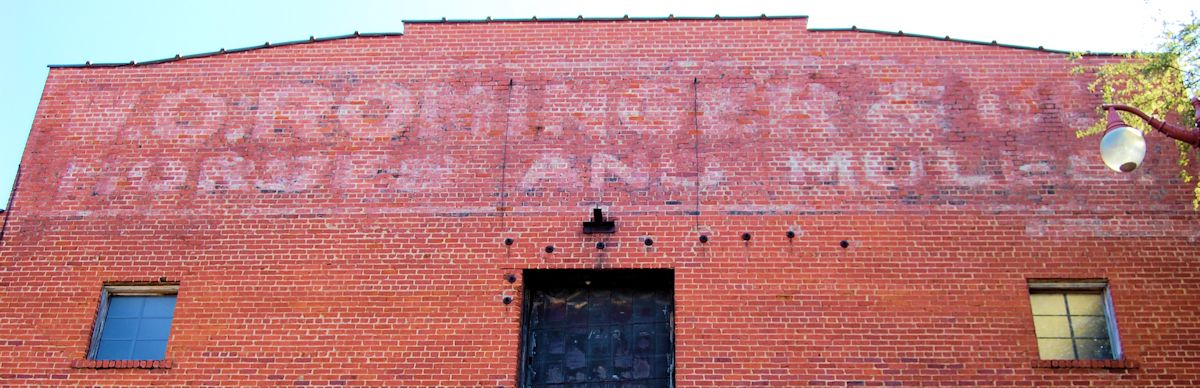

At the north end of the building is this sign for Rominger. Rominger, like Waddy Ross, was a prominent horse and mule dealer at the Stockyards early in the twentieth century.

At the north end of the building is this sign for Rominger. Rominger, like Waddy Ross, was a prominent horse and mule dealer at the Stockyards early in the twentieth century.

Coca-Cola bottle on the Los Vaqueros building (1915) on North Main. The building was built to be a slaughterhouse.

Coca-Cola bottle on the Los Vaqueros building (1915) on North Main. The building was built to be a slaughterhouse.

Meanwhile, on the other side of North Main Street, for beverage drinkers over age twenty-one, . . .

. . . there’s this Miller High Life sign. For a ghost sign tucked in an alley, it has a healthy tan. It’s on the back wall of the Maverick Hotel (1906) on Exchange Avenue.

This building (c. 1909) at 300 West Exchange originally housed the Stockyards branch of the post office and the grocery store of Frank Brooks.

This building (c. 1909) at 300 West Exchange originally housed the Stockyards branch of the post office and the grocery store of Frank Brooks.

The Stockyards area has the greatest concentration of ghost signs, but here are some located elsewhere:

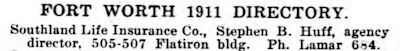

This building (1910) on Houston Street downtown once housed Atlantic Coffee Company, drugstores, and Thompson’s Bookstore. Joe Peters at the hat shop across the street told me he thought Southland was an insurance company. Southland also was a housing addition on the South Side.

This building (1910) on Houston Street downtown once housed Atlantic Coffee Company, drugstores, and Thompson’s Bookstore. Joe Peters at the hat shop across the street told me he thought Southland was an insurance company. Southland also was a housing addition on the South Side.

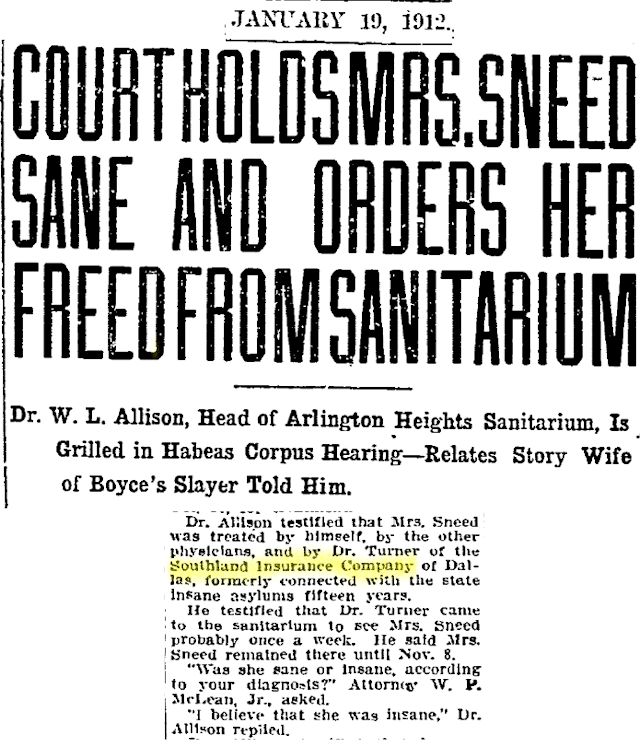

And indeed there was a Southland Insurance Company, mentioned in this report on the sanity hearing of Mrs. Sneed during the Boyce-Sneed feud.

And indeed there was a Southland Insurance Company, mentioned in this report on the sanity hearing of Mrs. Sneed during the Boyce-Sneed feud.

The company’s Fort Worth office was in the Flatiron Building one block south.

The company’s Fort Worth office was in the Flatiron Building one block south.

Standard Macaroni building on East Vickery Boulevard. One hundred years ago Standard Macaroni was a rival of nearby O.B. Macaroni.

Standard Macaroni building on East Vickery Boulevard. One hundred years ago Standard Macaroni was a rival of nearby O.B. Macaroni.

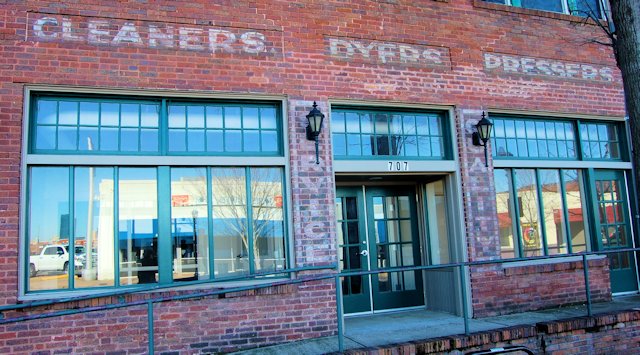

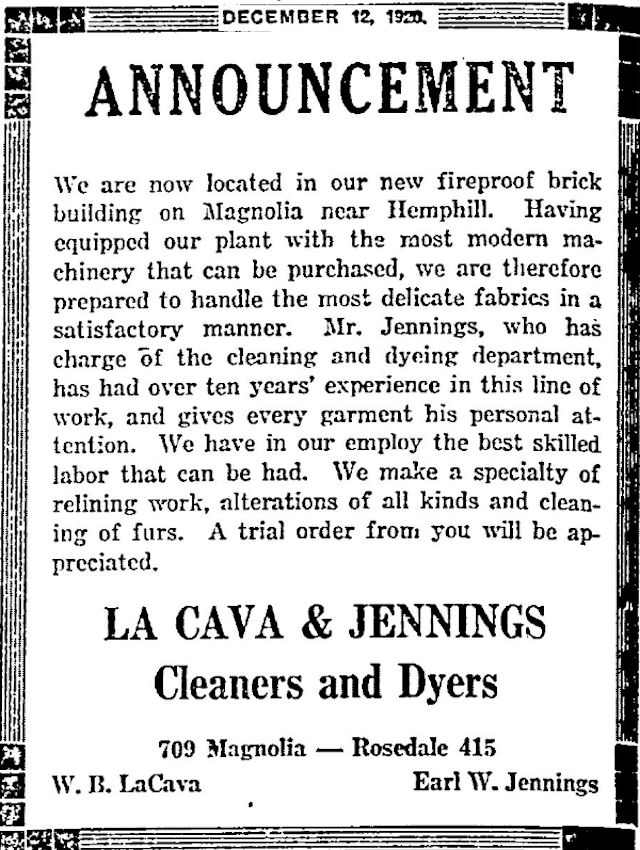

At 709 West Magnolia Avenue “service” and “quality” flanked the entrance of the dry cleaners of William Burts La Cava for more than fifty years.

At 709 West Magnolia Avenue “service” and “quality” flanked the entrance of the dry cleaners of William Burts La Cava for more than fifty years.

La Cava was a prominent entrepreneur of the near South Side. He opened his new business in his new building in 1920. In 1927 he built the La Cava Building next door at 1300 Hemphill Street. He also operated Magnolia Market neighborhood grocery at 1304 Hemphill. (And in a side business, La Cava sold dahlia seeds from his dry cleaners building!)

La Cava was a prominent entrepreneur of the near South Side. He opened his new business in his new building in 1920. In 1927 he built the La Cava Building next door at 1300 Hemphill Street. He also operated Magnolia Market neighborhood grocery at 1304 Hemphill. (And in a side business, La Cava sold dahlia seeds from his dry cleaners building!)

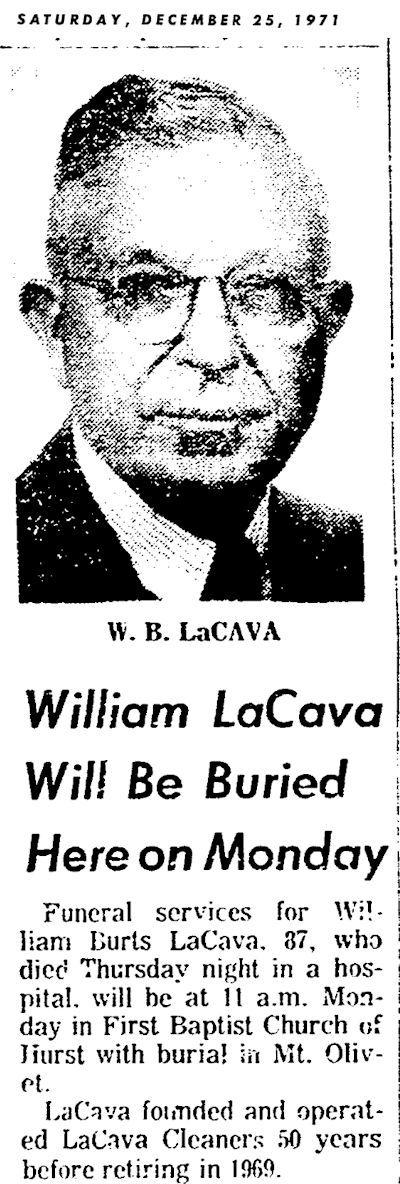

William Burts La Cava died in 1971. His cleaners closed soon after.

William Burts La Cava died in 1971. His cleaners closed soon after.

On Vaughn Boulevard in the former city hall (1914) of the town of Polytechnic, was Partlow’s Pastry Shop.

On Vaughn Boulevard in the former city hall (1914) of the town of Polytechnic, was Partlow’s Pastry Shop.

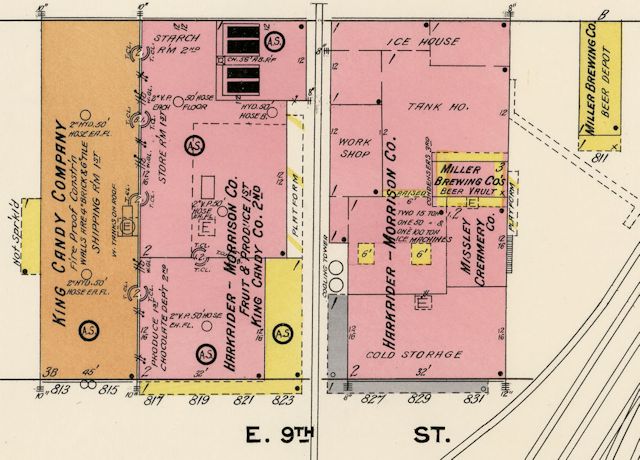

King Candy Company on East 8th Street.

King Candy Company on East 8th Street.

By 1911 the three-building King complex also housed the beer vault of Miller Brewing Company.

By 1911 the three-building King complex also housed the beer vault of Miller Brewing Company.

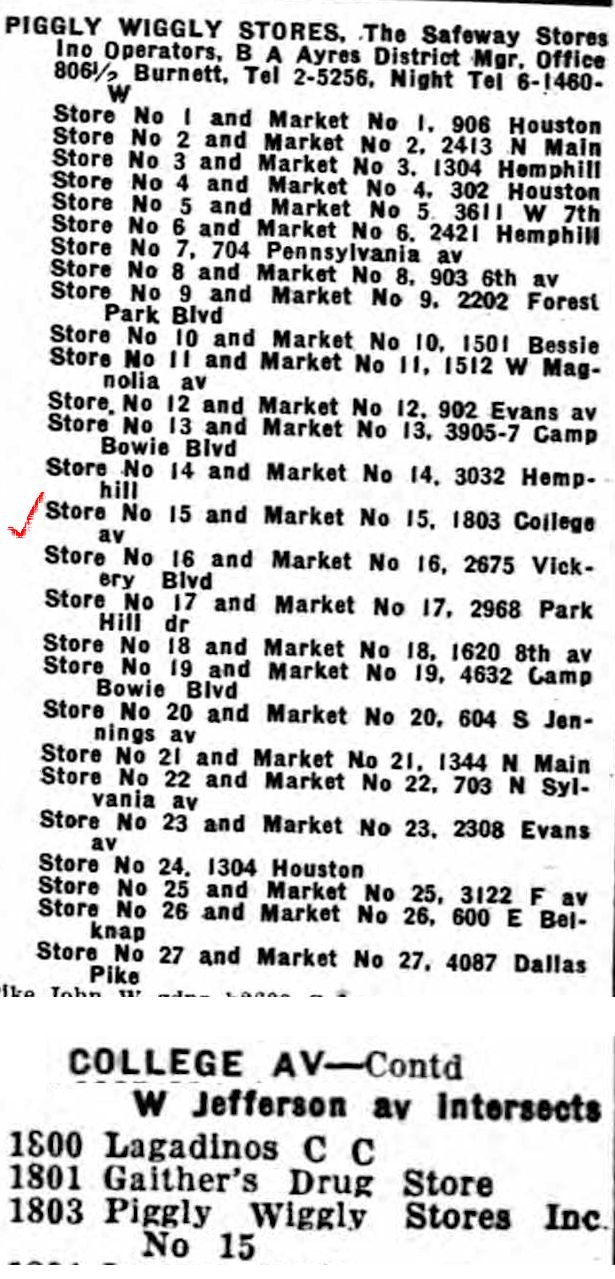

Back when neighborhood grocery stores flourished, an early Piggly Wiggly store was located in half of the Old Home Supply building (1925) on College Avenue. The Piggly Wiggly chain began in Memphis in 1916 as the first true self-serve grocery. Before this innovation, a shopper handed a list to a clerk, who fetched the items from shelves. Why “Piggly Wiggly”? According to one story, chain founder Clarence Saunders saw some piglets struggling to get under a fence, and the rhyming name occurred to him in a flash of porcine inspiration.

Finally, at 526 Jennings Avenue on the near South Side, you might pass this building (1913) and see nothing on the wall next to the parking lot.

Finally, at 526 Jennings Avenue on the near South Side, you might pass this building (1913) and see nothing on the wall next to the parking lot.

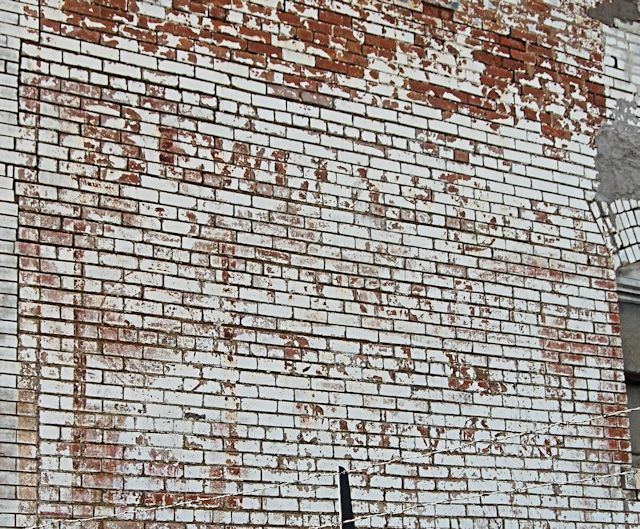

Here’s a closer look at that wall. Give it a good squint.

Here’s a closer look at that wall. Give it a good squint.

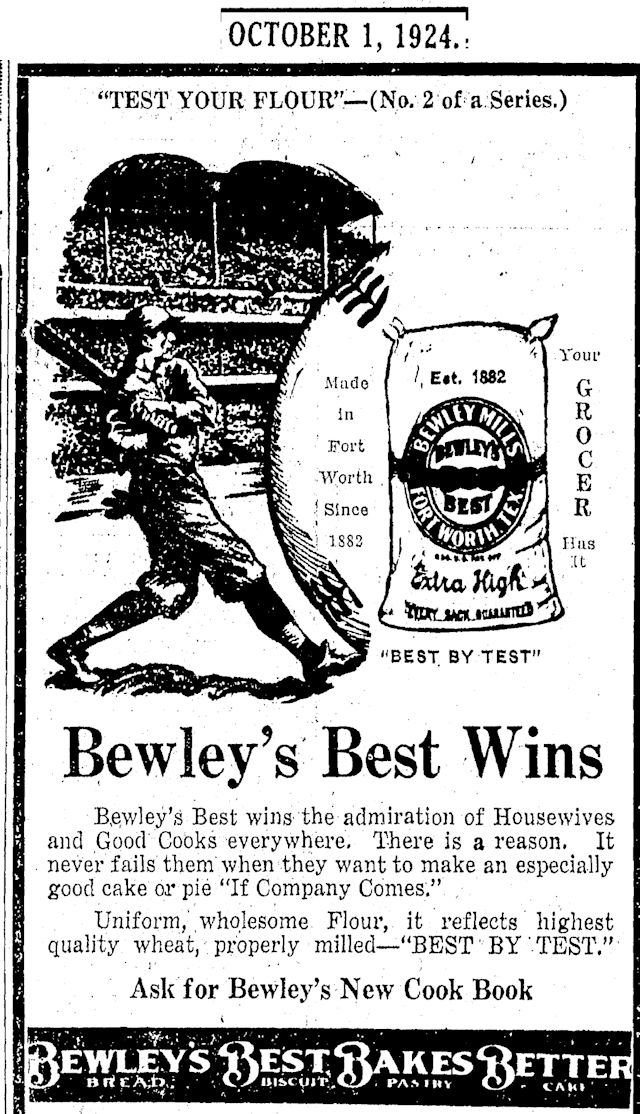

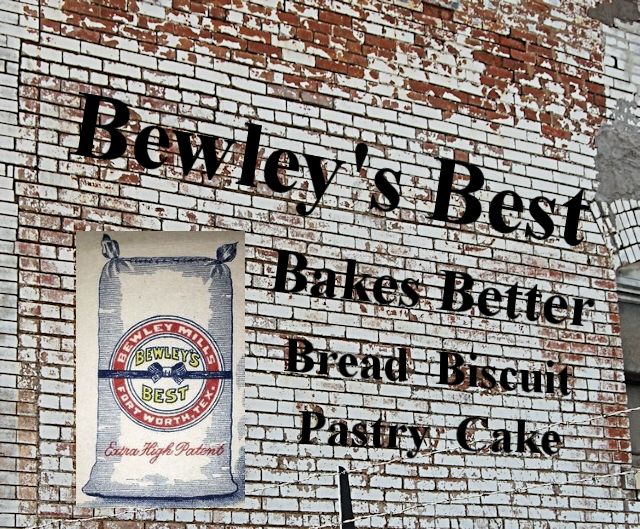

Based on my squint and on other Bewley advertising, I have superimposed the likely image and wording of the wall sign:

Based on my squint and on other Bewley advertising, I have superimposed the likely image and wording of the wall sign:

The mill founded by Murray Percival Bewley in 1882 produced flour, corn meal, and livestock feed in Fort Worth for eighty years. In the 1960s the Dunnagan family moved its iron works into this building, but the sign was painted on this building because for much of the building’s life it housed a neighborhood grocery store.

The mill founded by Murray Percival Bewley in 1882 produced flour, corn meal, and livestock feed in Fort Worth for eighty years. In the 1960s the Dunnagan family moved its iron works into this building, but the sign was painted on this building because for much of the building’s life it housed a neighborhood grocery store.

W.O. Rominger is my great grandfather who passed before I was born. I treasure every piece of history we can get our hands on regarding our family! I hope these old buildings continue to stand - it was awful watching his home be torn down to make way for the trinity river project. We are hoping someone will repaint the name so it will last another 100 years!

I hope that building is preserved and the signage gets a fresh coat of paint. There is so much construction going on next to it. My grandfather, mother, and father worked at the stockyards and packing plants.

Loved this post - I love seeing this kind of stuff when I am out walking or driving! I got some photos of the interior of some of the South Main buildings at Vickery during their renovation.

Thanks, Eric.

I really enjoyed your tour of ghost signs. Thank you!

Thank you, Pam.