It was Fort Worth’s coming-of-age celebration. In 1889 Fort Worth could count itself forty years old. Its population had grown to almost twenty-three thousand. It had eight railroads, streetcars, telephones, mills, a board of trade, a commercial club, an ironworks, tanneries, the Union Stockyards, seven ward schools, Fort Worth University, eighteen churches (and more lodges than churches) (and more saloons than lodges), 168 artesian wells, twenty-six miles of streets, fourteen miles of sewer, and an opera house. Fort Worth wanted to show the world (especially Dallas?) that Cowtown had become a cosmopolitan city and was no longer a git-along-little-dogie dusty cattle trail town.

So, city and railroad leaders produced the Texas Spring Palace exhibition and invited each county in the state to participate by displaying its natural resources, art, crops, and products in a grandiose exhibit hall that was longer than a football field.

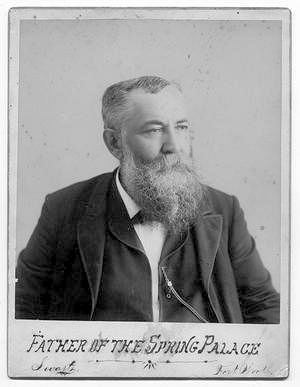

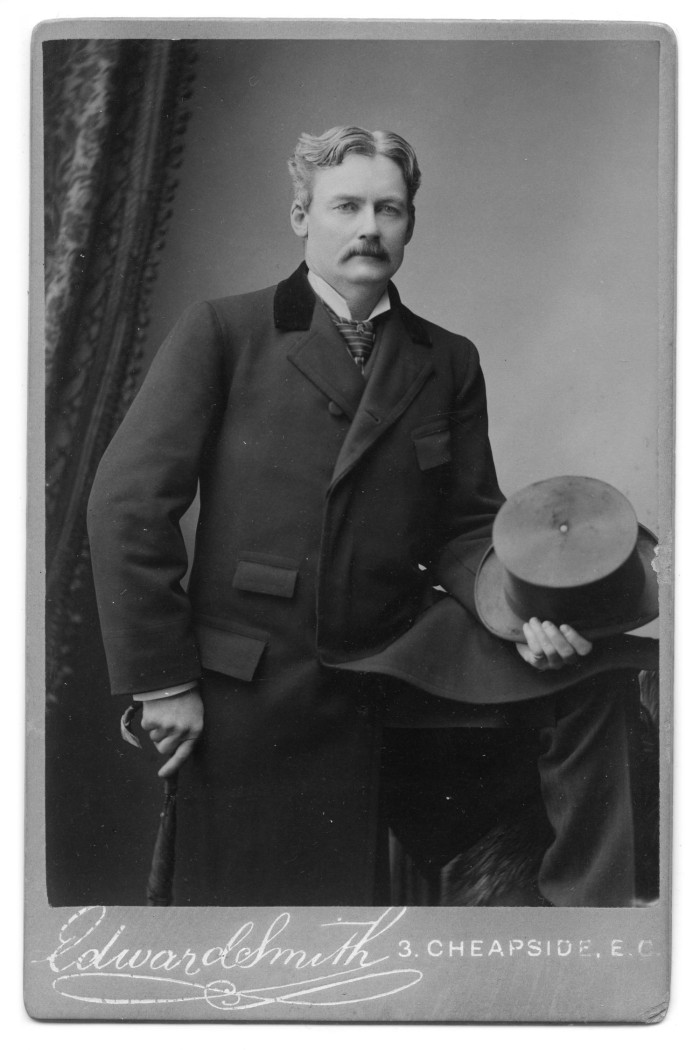

Brooklyn-born Robert A. Cameron, immigration agent of the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad, had come up with the idea for the exhibition. It was ostensibly an agricultural fair intended to promote all of Texas and to attract settlers and investors. But as the host city, Fort Worth naturally shared in the limelight and hoped to grab the panther’s share of glory, immigrants, and capital investment. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Brooklyn-born Robert A. Cameron, immigration agent of the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad, had come up with the idea for the exhibition. It was ostensibly an agricultural fair intended to promote all of Texas and to attract settlers and investors. But as the host city, Fort Worth naturally shared in the limelight and hoped to grab the panther’s share of glory, immigrants, and capital investment. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

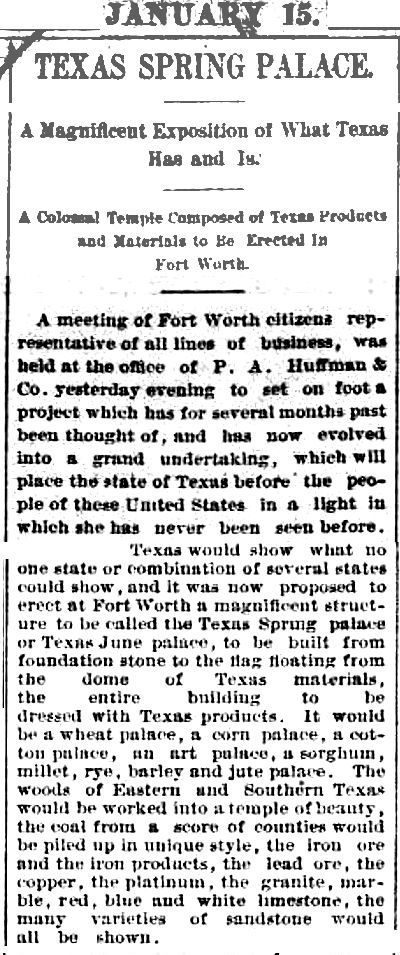

On January 15, 1889 the Gazette reported the general concept of the exhibition: “A magnificent exhibition of what Texas has and is.”

On January 15, 1889 the Gazette reported the general concept of the exhibition: “A magnificent exhibition of what Texas has and is.”

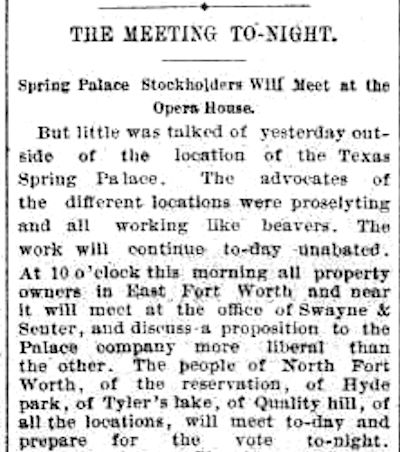

On February 25, 1889, with spring fast approaching, the site for the Spring Palace still had not been chosen. Among areas of town competing to host the exhibition (in addition to the Texas & Pacific reservation at the south end of downtown) were Sylvania east of Fort Worth, north Fort Worth, Tyler’s Lake, Hyde Park, even Quality Hill. Clip is from the February 26 Gazette.

On February 25, 1889, with spring fast approaching, the site for the Spring Palace still had not been chosen. Among areas of town competing to host the exhibition (in addition to the Texas & Pacific reservation at the south end of downtown) were Sylvania east of Fort Worth, north Fort Worth, Tyler’s Lake, Hyde Park, even Quality Hill. Clip is from the February 26 Gazette.

After the Texas & Pacific railroad reservation was chosen as the site, promoters of the Spring Palace didn’t dawdle: The Spring Palace was built in a flash (just thirty-one days) between Main and Jennings streets near the present-day 1931 passenger depot.

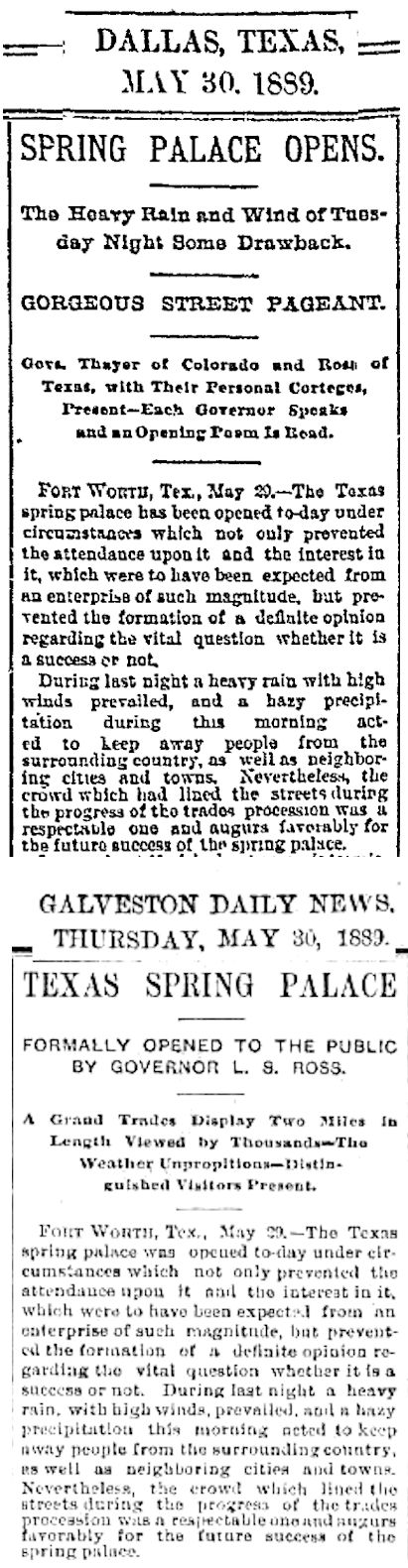

The Spring Palace opened on May 29, 1889. The May 30 Dallas Morning News and Galveston Daily News reported that nature was not kind to opening day. Special speaker was Governor Sul Ross, who as a Texas Ranger in 1860 had “freed” Cynthia Ann Parker.

Mexican President Porfirio Diaz and U.S. President Benjamin Harrison were invited to attend the exhibition. One tower of the Spring Palace was dedicated to Diaz, another to Harrison.

Both presidents were no-shows.

The show went on without them.

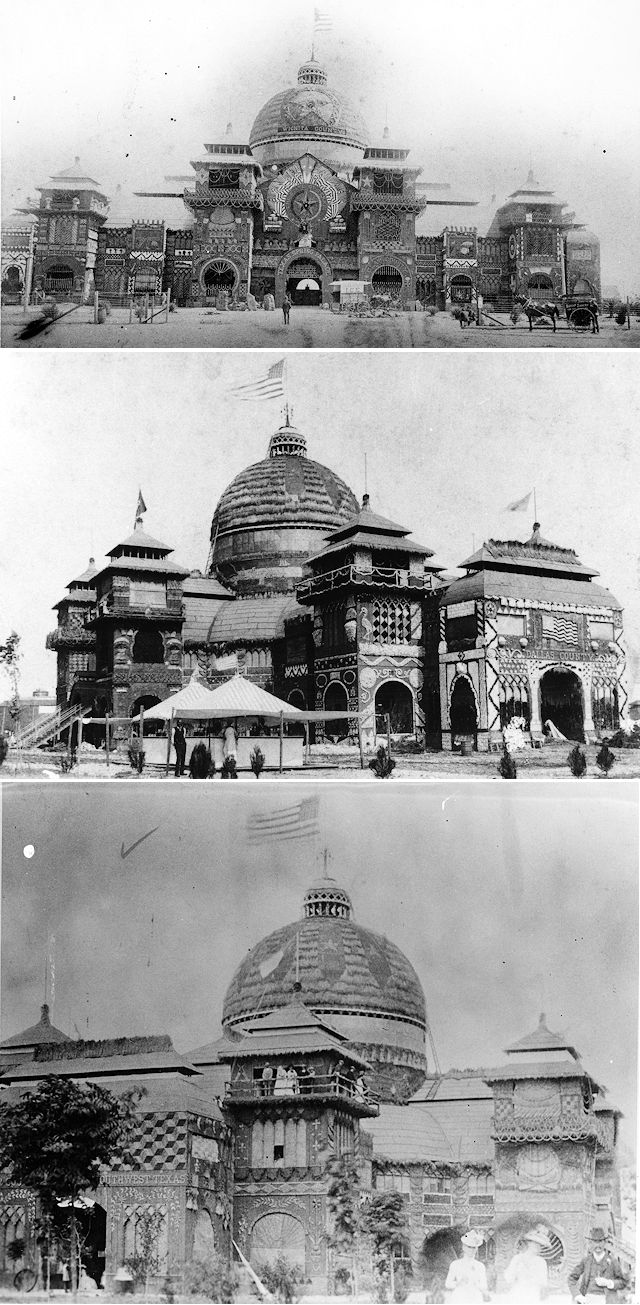

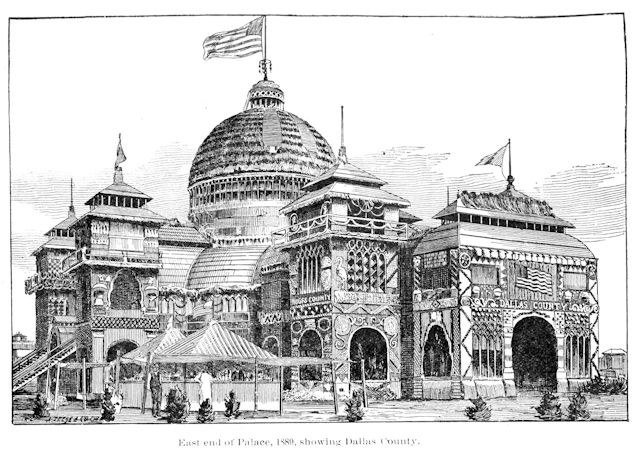

British-born architect Arthur Arthur Albert Messer (1863-1934) designed the sprawling wooden building. It was a dizzying blend of Victorian and Asian styles that featured arches, columns, balconies, cupolas, round portals, square pagoda-like bays, and flags atop spires. High over the center was the Moorish-style Grand Dome, which was 155 feet high and surpassed in size only by the dome of the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

British-born architect Arthur Arthur Albert Messer (1863-1934) designed the sprawling wooden building. It was a dizzying blend of Victorian and Asian styles that featured arches, columns, balconies, cupolas, round portals, square pagoda-like bays, and flags atop spires. High over the center was the Moorish-style Grand Dome, which was 155 feet high and surpassed in size only by the dome of the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

(Photos from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

The 1890 book The Texas Spring Palace gushed about that Grand Dome: “the great dome pierces the blue of Texas skies with its banner-surmounted pinnacle of blue and gold. The interior of the dome is lined with golden grains and grasses, woven into pleasing designs.”

Inside and out, surfaces of the building were covered with mosaics made from the natural resources, products, crops (corn stalks, cactus, moss, Johnson grass, cotton, wheat), and art of each county of the state.

Oh, and if that word karporama on the poster above suggests to you a fishing tournament for bottom-feeders, karporama is actually a neologism unique to the exhibition, a combination of the Greek karpos (fruit) and rama (view), an allusion to all those mosaics made of Texas agricultural products. (Poster from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room.)

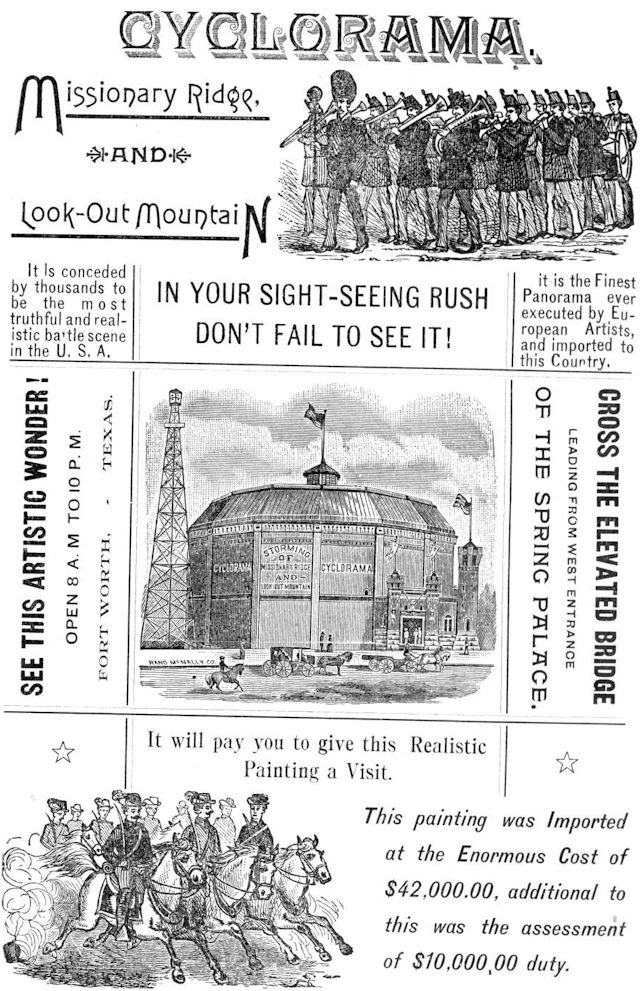

Adjacent to the karporama was another rama: the cyclorama, which was a round auditorium whose interior wall was covered by an oil-on-canvas wraparound mural depicting the Civil War’s Battles of Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain (two Union victories in 1863). Remember that in 1889 those two battles were only twenty-six years in the past. Some of the people viewing the mural may have fought in or lost loved ones in those battles. The cyclorama was one of the Spring Palace’s more popular attractions. (Illustration from the 1890 book The Texas Spring Palace, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Adjacent to the karporama was another rama: the cyclorama, which was a round auditorium whose interior wall was covered by an oil-on-canvas wraparound mural depicting the Civil War’s Battles of Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain (two Union victories in 1863). Remember that in 1889 those two battles were only twenty-six years in the past. Some of the people viewing the mural may have fought in or lost loved ones in those battles. The cyclorama was one of the Spring Palace’s more popular attractions. (Illustration from the 1890 book The Texas Spring Palace, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

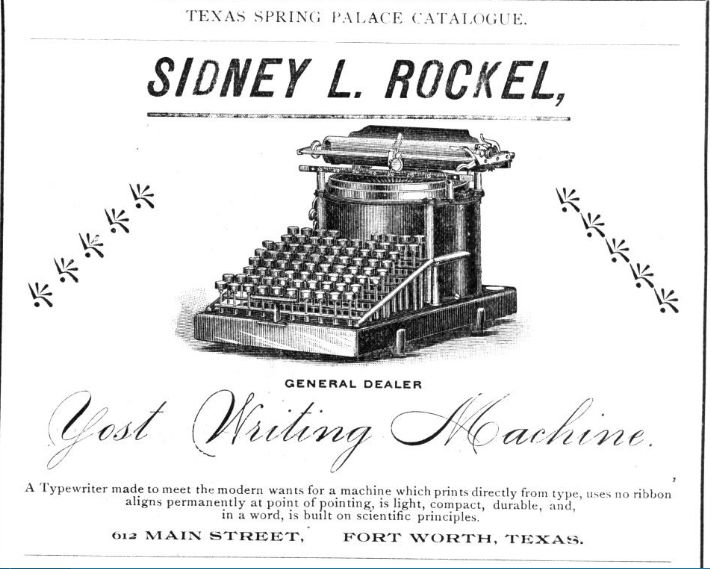

In this ad in the book Sidney L. Rockel showed off the latest in word-processors.

In this ad in the book Sidney L. Rockel showed off the latest in word-processors.

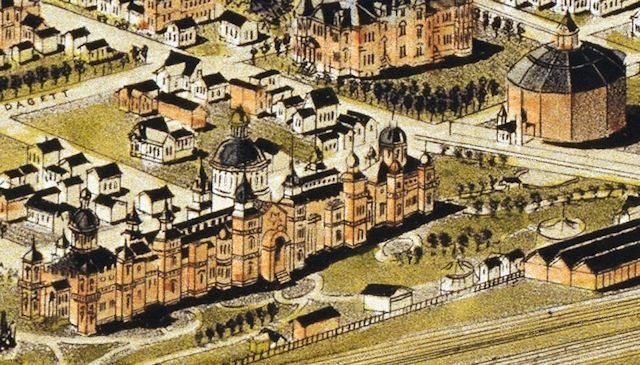

This 1891 American Publishing Company bird’s-eye-view map shows both karporama and cyclorama.

This 1891 American Publishing Company bird’s-eye-view map shows both karporama and cyclorama.

The eclectic, exotic karporama was, in the modest assessment of Spring Palace president B. B. Paddock, “easily the most beautiful structure ever erected on earth.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The eclectic, exotic karporama was, in the modest assessment of Spring Palace president B. B. Paddock, “easily the most beautiful structure ever erected on earth.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

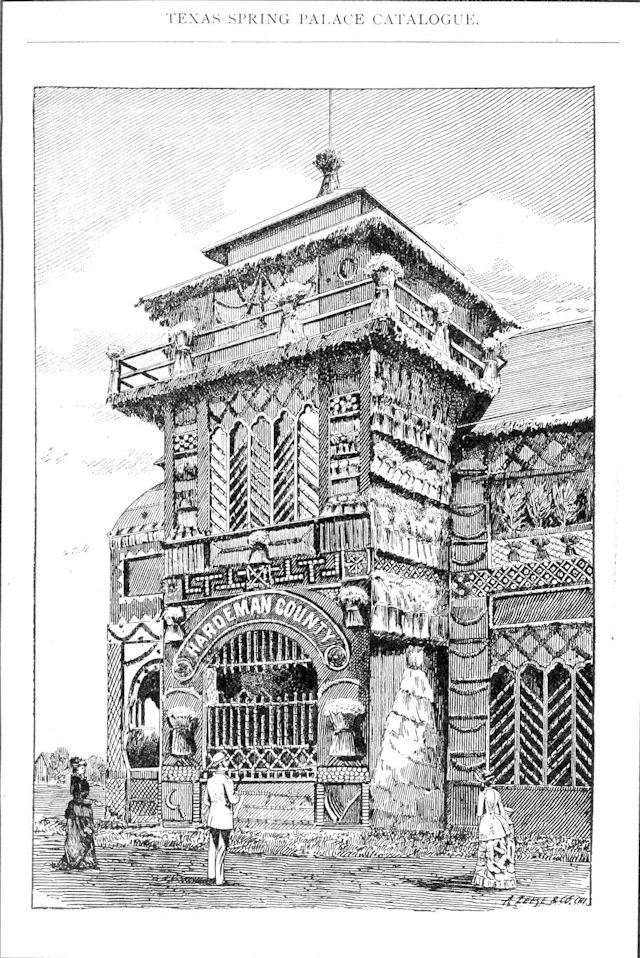

The festooned tower of Hardeman County.

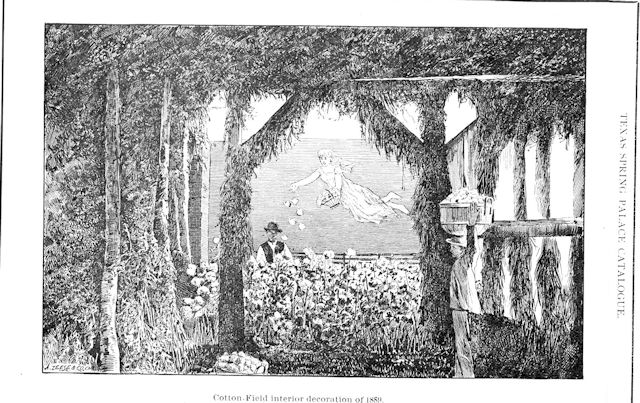

The festooned tower of Hardeman County. Cotton field simulation.

Cotton field simulation. East end of the palace, including the Dallas County tower.

East end of the palace, including the Dallas County tower.

Over fifty counties participated in the wingding; some counties paid a premium to display their wares in one of the building’s twenty-two towers. Entertainment included concerts by the Mexican National Band and the Elgin Watch Factory Band, singing, political and religious orations, sporting events, and dancing. Exhibits included a prairie dog village, a miniature lake stocked with fish, and Sam Houston’s walking cane. (Illustrations from The Texas Spring Palace.)

Display tables. Note the dried vegetation. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Display tables. Note the dried vegetation. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

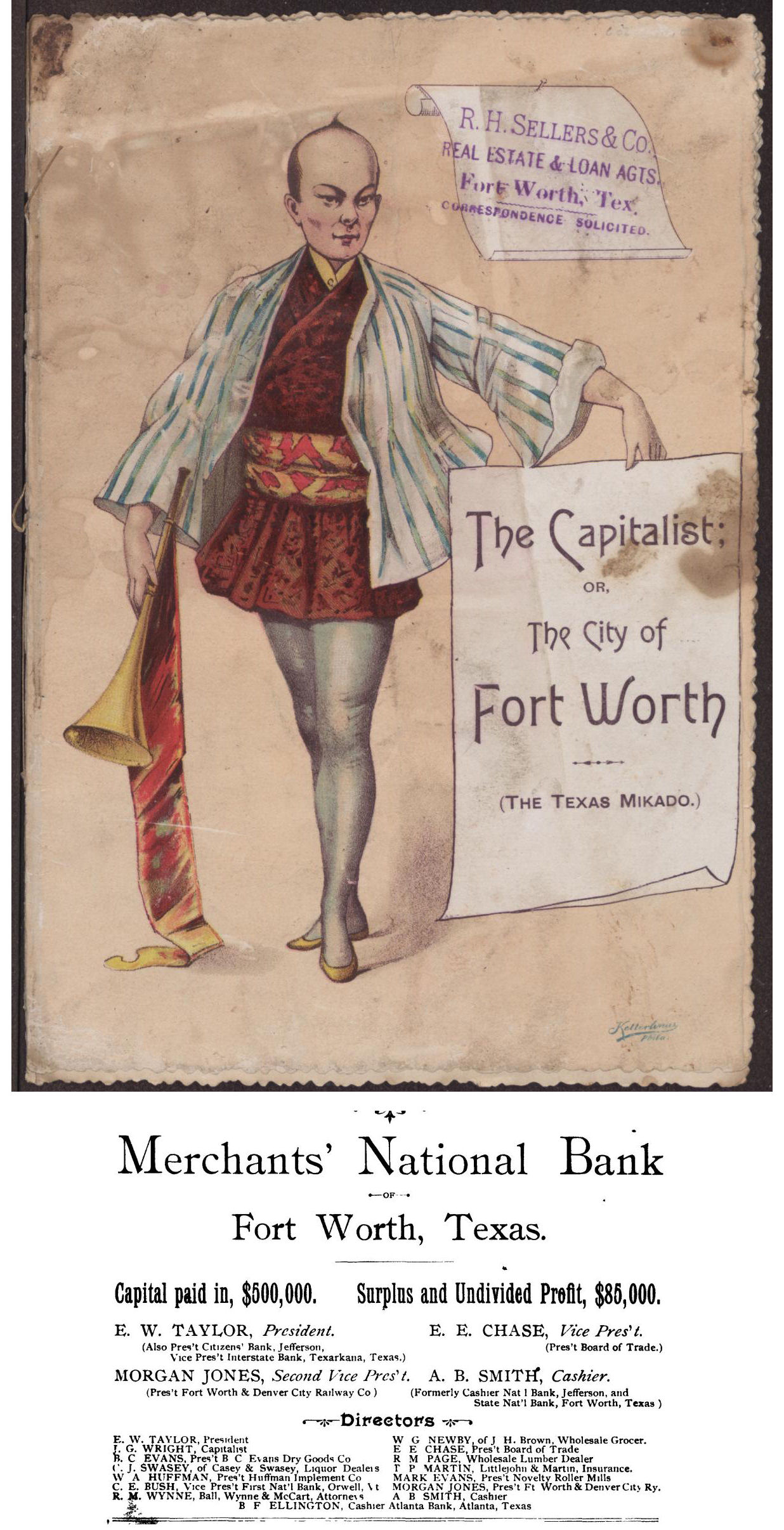

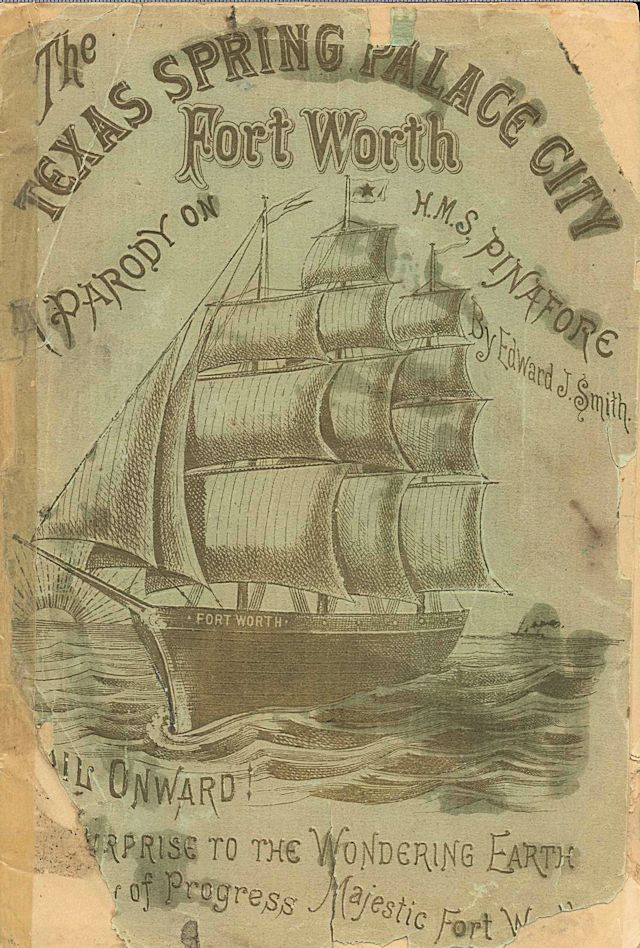

To complement the palace and its Asian trappings, Fort Worth even produced two plays. For the first season in 1889 The Capitalist, or the City of Fort Worth (The Texas Mikado), a parody of Gilbert and Sullivan’s play, extolled the virtues of Fort Worth and downplayed its wild West beginnings. The play featured characters such as Peek-A-Boo, By-Gum, Yankee-Doo, and Kokonut. For the second season in 1890 the city presented The Texas Spring Palace City, Fort Worth, a parody of Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore with characters such as Dick Badegg, Colonel Longhorn, Captain Bigbug, and Little Chilitop. (Photos from Star of the Republic Museum and Amon Carter Museum.)

To complement the palace and its Asian trappings, Fort Worth even produced two plays. For the first season in 1889 The Capitalist, or the City of Fort Worth (The Texas Mikado), a parody of Gilbert and Sullivan’s play, extolled the virtues of Fort Worth and downplayed its wild West beginnings. The play featured characters such as Peek-A-Boo, By-Gum, Yankee-Doo, and Kokonut. For the second season in 1890 the city presented The Texas Spring Palace City, Fort Worth, a parody of Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore with characters such as Dick Badegg, Colonel Longhorn, Captain Bigbug, and Little Chilitop. (Photos from Star of the Republic Museum and Amon Carter Museum.)

The first season of the Texas Spring Palace exhibition closed on July 4, 1889 and was deemed a success, despite losing $23,000 ($587,000 today). Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

The first season of the Texas Spring Palace exhibition closed on July 4, 1889 and was deemed a success, despite losing $23,000 ($587,000 today). Clip is from the July 4 Gazette.

In fact, for the Texas Spring Palace’s second season in 1890, the palace was enlarged on each of its four wings. The cross-shaped building was now 375 feet wide and 225 feet deep. That meant more wood. More dried grasses. More paper and fabric. Clip is from the May 18 Gazette.

In fact, for the Texas Spring Palace’s second season in 1890, the palace was enlarged on each of its four wings. The cross-shaped building was now 375 feet wide and 225 feet deep. That meant more wood. More dried grasses. More paper and fabric. Clip is from the May 18 Gazette.

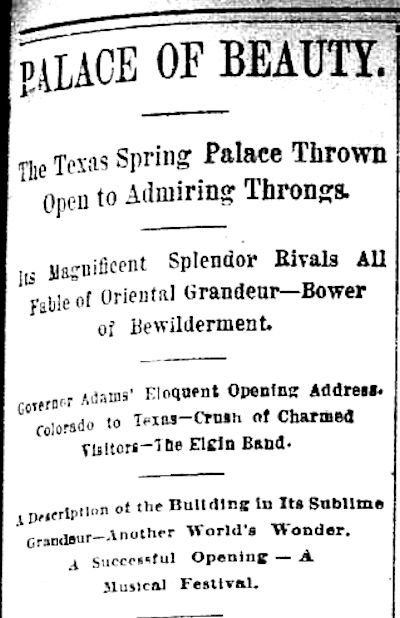

The second season opened on May 10, 1890 with the Gazette trotting out every superlative it could roll some ink over. Many businesses closed so that employees could attend the opening. Note that just as in 1889, the governor of Colorado was a keynote speaker at this Texas-intensive Woodstock of commerce. But remember that the Spring Palace was the brainchild of a Fort Worth & Denver City railroad official. The railway had begun service between its two namesake cities in 1888. Clip is from the May 11 Gazette.

The second season opened on May 10, 1890 with the Gazette trotting out every superlative it could roll some ink over. Many businesses closed so that employees could attend the opening. Note that just as in 1889, the governor of Colorado was a keynote speaker at this Texas-intensive Woodstock of commerce. But remember that the Spring Palace was the brainchild of a Fort Worth & Denver City railroad official. The railway had begun service between its two namesake cities in 1888. Clip is from the May 11 Gazette.

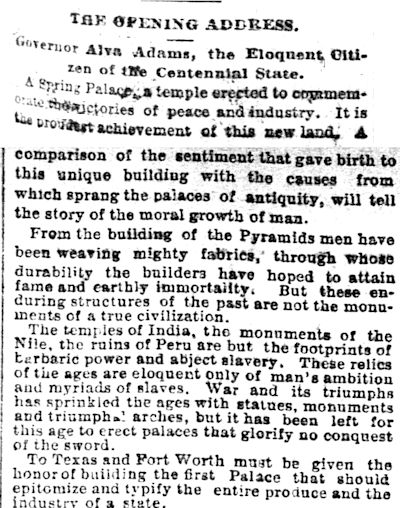

The Gazette was not the only one waxing eloquent. On May 11 the newspaper printed the text of Colorado Governor Adams’s speech, which began thusly.

The Gazette was not the only one waxing eloquent. On May 11 the newspaper printed the text of Colorado Governor Adams’s speech, which began thusly.

But in truth it would be difficult to overstate what an eye-popping, jaw-dropping, cliché-generating big deal this, Fort Worth’s first extravaganza, was at the time. Think Mayfest with buggies. Think Main Street Fort Worth Arts Festival with bustles. Think State Fair of Texas under one roof—the roof of a building that made Cowtown resemble Baghdad-on-the-Trinity.

For the rest of the month of May 1890 the Gazette devoted hundreds of column inches to the exhibition, covering the special railroad excursions, the presentation of medals for a wide range of competitions, the praises of the exhibition printed in other Texas newspapers, the special days declared for Texas cities, for members of fraternal lodges, for orphans, for railroad workers, etc. The exhibition was state and even national news.

For example, on May 18, 1890 an entourage of northwestern Kansas journalists numbering 110 stepped off the train to attend the exhibition.

The headlines of the May 18 Gazette used the words glory and glorious to describe the Texas Spring Palace.

The headlines of the May 18 Gazette used the words glory and glorious to describe the Texas Spring Palace.

But fate—and one small boy—had far more “glory” in store for “the most beautiful structure ever erected on earth”:

Just amazing.