We have no photo of him, no obituary or tombstone. The great gumshoe Google digs up little on him. Newspaper archives at the Library of Congress draw a blank. Ancestry.com searches the past for him in vain.

Most of what we know about George S. Stiers is what he told an interviewer of the Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s when Stiers was living at the Tarrant County Home.

Some background on the Tarrant County Home: The 1869 Texas Constitution authorized county poor farms as a form of public assistance for the indigent (usually elderly) and occasionally for prisoners. Families and children were rare among residents. These were working farms: Residents grew their own food. But with changes in federal and state public relief laws in the 1930s, poor farms became less necessary. One by one, poor farms were closed or were converted to other county institutions, their buildings were razed, and their land turned to other use. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Tarrant County’s poor farm operated from about 1879 on Kimbo Road just east of Sylvania Avenue.

Tarrant County’s poor farm operated from about 1879 on Kimbo Road just east of Sylvania Avenue.

![]()

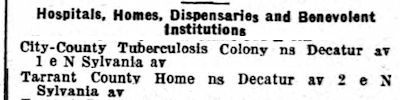

By 1920 the facility had become the Tarrant County Home for indigent elderly. The county also maintained a tuberculosis colony on the property and later Elmwood Sanitorium for tuberculosis patients. Elmwood later had a psychiatric ward. A few buildings of the facility remained into this century. Now only a few stones (photo) are left to show where the entry gates stood on Kimbo Road (called “New Denton Road” and “Decatur Avenue” into the 1940s).

By 1920 the facility had become the Tarrant County Home for indigent elderly. The county also maintained a tuberculosis colony on the property and later Elmwood Sanitorium for tuberculosis patients. Elmwood later had a psychiatric ward. A few buildings of the facility remained into this century. Now only a few stones (photo) are left to show where the entry gates stood on Kimbo Road (called “New Denton Road” and “Decatur Avenue” into the 1940s).

Because poor farm/county home residents were elderly and indigent, the Tarrant County facility had its own cemetery, although record-keeping was lax, and graves were not always marked.

Because George Stiers was seventy-three when he was interviewed and living in an indigent facility after a hard life, it is quite possible that he died at the Tarrant County Home and was buried there.

After the Tarrant County poor farm/county home closed, its dead were moved to unmarked pauper graves at Mount Olivet and to Oakwood Cemetery’s block 55 (photo). County governments have long provided pauper burials for the indigent and unclaimed.

After the Tarrant County poor farm/county home closed, its dead were moved to unmarked pauper graves at Mount Olivet and to Oakwood Cemetery’s block 55 (photo). County governments have long provided pauper burials for the indigent and unclaimed.

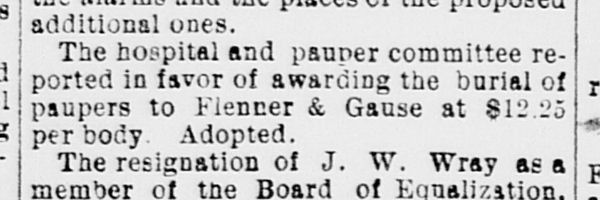

This Fort Worth Gazette clip detailing the minutes of a city council meeting is from 1887. And, yes, that is the George Gause who opened the first funeral home in Fort Worth in 1879.

This Fort Worth Gazette clip detailing the minutes of a city council meeting is from 1887. And, yes, that is the George Gause who opened the first funeral home in Fort Worth in 1879.

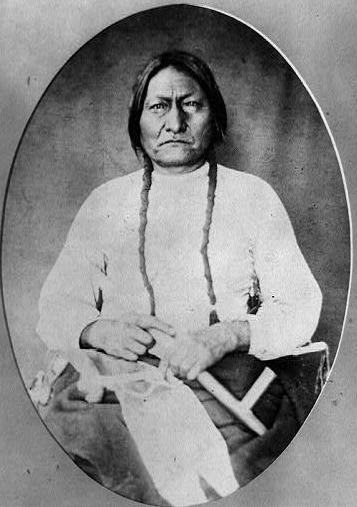

George S. Stiers told the Federal Writers’ Project interviewer that he was born on January 8, 1864 as “Tella Wabasha” (Red Wolf) on the Pine Ridge, South Dakota, Native American reservation.

Stiers said his mother, a Sioux, was a granddaughter of Sitting Bull (pictured). In 1879 Tella Wabasha left the reservation and became “George Stiers” (taking the surname of his father, a French-Canadian).

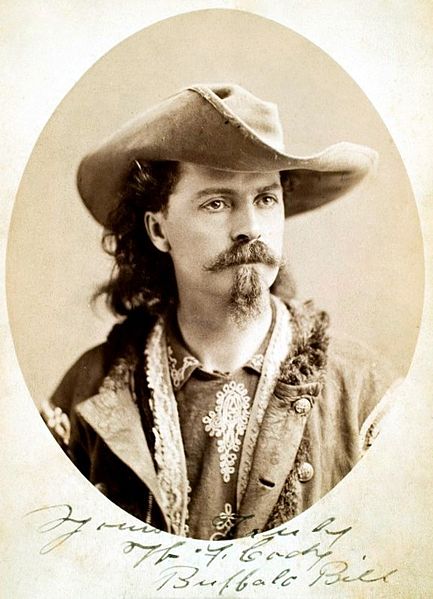

Also that year, George Stiers, at the suggestion of his father, sought out William “Buffalo Bill” Cody (pictured).

Here is the story of George S. Stiers in his own words:

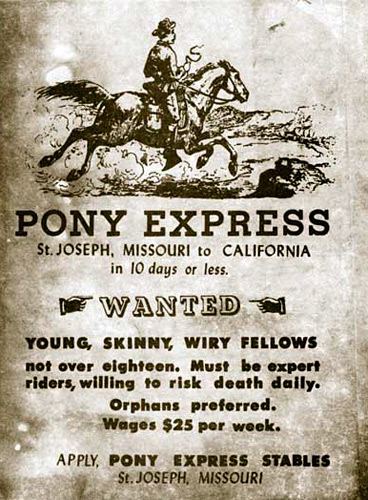

“He [George’s father] said that Bill would help me find something to do. . . . When I told Bill what I had on my mind, he said that the Pony Express people could use a good rider, one that could stand hard riding, was not yellow, and could shoot fast and straight.”

So, at the age of fifteen Stiers became a Pony Express rider. Cody signed the $1,000 bond that the Pony Express required from riders. “My trail was between Fort Dodge and Wichita, Kansas,” Stiers recalled. “The distance was a trifle over one hundred miles, and we rode in ten hours. There were twelve change stations, located about eight miles apart, where we changed hosses.”

During three years on the Pony Express, Stiers was robbed twice and shot once: “I was riding into Fort Dodge and had about eleven miles to go and one more change to make three miles ahead. A fellow suddenly jumped me from behind a bunch of buffalo grass about fifteen yards ahead of me and yelled ‘Reach high!’ I reached and slowed my hoss, but as I got close to the fellow I threw myself forward onto the hoss’s neck and at the same time put the gut hooks to it. My hoss reared and leaped forward, and at the moment the fellow shot. The hoss hit the bandit, knocking him down, and the bullet hit me. It parted my hair, striking me at the top of the forehead, where that scar is, and skirted back off of my head.

“The last thing I remembered was the hoss rearing and hearing the shot. When I came to my senses I was in the post hospital at Fort Dodge [Kansas]. The boys at the change station, three miles down the rode, told me I came in riding at top speed laying forward and hanging to the saddle horn with one hand and the mane of the hoss with the other. I had blood all over me and the front of the hoss and held such a tight grip they had to pry my hands loose.

“I stayed in the hospital for five days and then was out again as good as ever, except for a sore spot on my head.

“Buffalo Bill came to see me while I was in the hospital and had a talk with me about quitting. I was not much stuck on the idea of quitting. I sort of hankered after the job. To me it was the real thing and gave me excitement. But Bill says, ‘Boy, I got you into this, and I am going to get you out before you get cut down. I am going to take down the bond if you don’t quit of your own accord.’

“That left nothing to do but quit or find another bondsman. Bill had proved to be such a good friend, and I sort of wanted to do as he said, so I quit.”

George Stiers quit riding for the Pony Express in 1881 and became a government scout (painting by Frederic Remington). Stiers recalled: “The later part of my scout work was watching for bandits, and the most exciting time I had doing that work concerned Buffalo Bill. I came to a rise just about sundown and looking off a distance I saw dust, which told me it was from a number of hosses traveling, and I was sure it was a party of Indians. I hit for the dust, and by the time I reached the trail it was dusk. The number of tracks showed there were about fifty in the party. I decided to see what it was all about and hit to follow it. I followed it about five miles and then sighted a fire. Upon reaching the fire I saw where there were several fires recently put out and one left burning next to a hole in the side of a hill.

“Something urged me to look into the hole. I crawled in and came in contact with a body, then I took hold of the leg and dragged it out into the open. By that time my lungs and eyes were full of smoke, and I was choking and blinded. When I got my wind and eyes cleared there laying at my feet was my friend Buffalo Bill. He wore his hair and beard long, and it was black.

“The one side of his head and face was burned. No sign of life was indicated. I cupped my mouth over his and blew air into his lungs and sucked it out again. I kept that up for several minutes and was about to give up when I felt a muscle twitch. I says, ‘Thank God, he is not dead.’ Then I went to work in earnest, and in a little while he began to breathe. In fifteen minutes or so he was sitting up.

“He was plenty pale around the gills and weak. I knew that the Indians had put Bill in that shape but was curious to know why they did not put a finish on the job. I says, ‘Bill, who did this, and what has happened?’ He tried to talk but was unable to say a word and was trying hard. Finally he got out, ‘hunting party. Winnebago’ was all that he could say.

“I put him on my hoss and took him to Fort [Hays?], which was the nearest post. By the time we reached the post he was feeling tolerably well and in a couple days was pert again, except for the tender spot when the beard and hair had been burned.

“He told me what took place. He . . . came across the Indian hunting party. He was not expecting anything to happen, and they took him by surprise, caught and tied him. They calculated on revenging an old grudge held against him for killing Chief Yellow Hammer in a fight when he was with General Miles in 1876. The Indians took him to their camp and I reckon were bent on killing him but must have sounded the ground and heard me a-coming.”

Buffalo Bill was forever grateful to Stiers for saving his life. Stiers recalled:

“Many times in the after years, he would tell me, ‘Wolf, I am living my life but breathing your air.’”

George Stiers then worked as a cowboy for Panhandle rancher Charles Goodnight. Then Stiers joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show (photo). For six years he performed a riding and shooting act. He recalled:

“I joined Bill’s show in 1891 and stayed with him eight years. . . . O. B. Gray was one of the featured shots working with Annie Oakley. I was also featured shot and rider. ‘Indian Chief Wolf’ was what I was billed under. My best shot was to throw two glass balls in the air, shoot one while up and wait for the other to drop to about three feet off the ground, then drop my gun and get it. Also, I would flip a quarter-dollar—phony, of course—in the air and make it disappear. A glass ball, which is rosin, will break and fall, but a coin goes out of sight with the bullet.

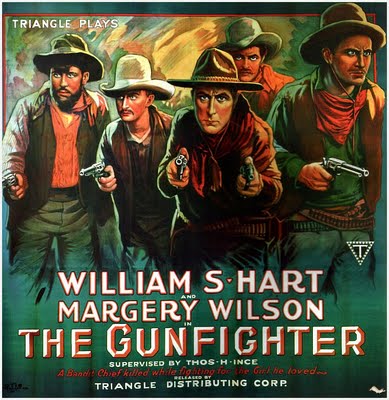

“After I quit Bill’s show I went to Los Angeles and joined William S. Hart in the production of his two-reel Western pictures. I did riding and cowboy stuff, also shooting. I stayed with Hart until he quit production, then I went on the vaudeville circuit, . . . then the vaudeville played out, and that ended my active career.”

Hart was active as an actor, director, and producer into the mid-1920s. At some point after that, somehow Stiers, after his remarkable career, ended up at the Tarrant County home for the elderly. He told the Federal Writers’ Project interviewer: “All I do now is sit here visiting with the other old men and look at them pictures, which gets me to dreaming of the past. I think of the old boys in their play and stories they would tell sitting around the campfire.”

By his own account of his life (and I have not found anything to support or cast doubt on his account), George S. Stiers, the man who was born “Red Wolf,” had a lot of past to dream of.

Wow, such a great story with a sad ending. Makes you want to know how he wound up in Ft. Worth.

Thanks, Scott. It’s quite a story, perhaps the rip-roaringest of all those in the Verbatim category. Folks born in the mid-1800s who lived a long life were able to tell us about the real “wild West.”

Bruce: Isn’t that a treasure? I have found a few such gems in the Federal Writers’ Project that I will post here. In the 1930s there were folks still alive who had lived the real West. Alas, in most cases we have only their word, given to the interviewer.

Wow! What a life! Puts me in mind of the movie version of “Lonesome Dove.”