Pioneer Fort Worth attorney J. C. Terrell was born in Tennessee in 1831 to Dr. Christopher Joseph and Susan Kennerly Terrell as the Terrell family was moving from Virginia to Missouri. He studied law under his brother Alexander, who would become U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) under President Grover Cleveland.

In 1852 J. C. Terrell, age twenty, went west to California, like so many others, to prospect for gold. His journey with two other men from Missouri to the gold fields in a covered wagon—the minivan of its day—took three months. There were no roadside parks, Dairy Queens, Cracker Barrels, motels, AAA roadside assistance, washaterias, or restrooms. Just ninety days of “Does that bear look hungry?” and “Do those natives look angry?” and “Are we there yet?”

In 1852 J. C. Terrell, age twenty, went west to California, like so many others, to prospect for gold. His journey with two other men from Missouri to the gold fields in a covered wagon—the minivan of its day—took three months. There were no roadside parks, Dairy Queens, Cracker Barrels, motels, AAA roadside assistance, washaterias, or restrooms. Just ninety days of “Does that bear look hungry?” and “Do those natives look angry?” and “Are we there yet?”

Terrell recalled:

“Most of the California, Salt Lake, and Oregon emigrants bought their outfit, a matter of great importance for a journey of sixteen hundred miles through a wilderness, where neither love nor money could procure the necessaries of life. My company was composed of three: A. Fuqua, a widower, farmer, 35 years old; Powhatan B. Whitehead, a cowboy, 23, and myself, 20 years old. I owned most of the outfit. Our wagon was well covered and had sideboards extending over the wheels, affording room for sleeping in rainy weather, but ordinarily we preferred sleeping on the ground. We had three yoke of oxen, one yoke of milch cows, a good dog Ranger, a few extra yoke bows, some small rope, two horses, some extra horseshoes and nails, axe, hatchet, auger and a few other things in that line in the tool box. As for medicines, five gallons of pure cognac brandy, some Tutt’s pills [a patent medicine] and a few bottles of lemon syrup and acetic acid to counteract alkali water, constituted our dispensary.

“Thinking the trip to Sacramento City could be made in four months, provisions were laid in accordingly, consisting of flour in sacks, prepared corn meal, dried fruit, rice, beans, coffee, tea, bacon, etc.”

The trip was arduous. Terrell wrote:

“The officials at Fort Kearny [Nebraska] estimated that over 31,000 people, of both sexes and all ages, passed overland this year. The number that died can never be known. I saw hundreds of newly-made graves. In some instances the remains were buried so shallow that they were scratched up and devoured by wolves, the torn shrouds and bones being all that was left. Seeing this, some would haul rocks from a distance to place on the graves of their dead, and thus baffle the wolves.”

Justice along the trail was swift:

“To illustrate: One morning, cooking breakfast, two partners quarreled. One, stooping over a skillet, was, from behind, stabbed to the heart. His slayer was immediately disarmed and his hands tied. A man who had presided as Judge in Illinois, a stranger, was forced to preside as Judge, and attorneys appointed to prosecute and defend; a jury of twelve men, also strangers, were empaneled; and, after argument and charge, the defendant was found guilty and sentenced to be hung which was done instanter, from two elevated wagon tongues tied together, the forewheels scotched with ox-yokes, for there were neither trees nor rocks. The foregoing, set out in legal parlance and signed by the judge and jury and tacked to a board, was placed on the grave.”

In 1856 Terrell returned east to visit his family in Virginia. In 1857 he again headed west to the golden glitter of California. But en route he stopped in Fort Worth, where he ran into an old schoolmate, Dabney C. Dade. The two young lawyers formed the law partnership of Terrell & Dade in the “hamlet” of about three hundred that was growing up around an abandoned Army fort. The nearest railroad, Terrell wrote, was more than two hundred miles away. The free land available in Peters Colony attracted “a superior class of early settlers,” he wrote, and thus, “It was not unusual to meet higher culture in a cabin and to see pianos on dirt floors.”

Terrell and Dade could find no office for their new law firm, so they had one built: “I hired a man named John Branon, and in a few weeks had a two-room office building, with chimneys, on the corner of First and Main streets. The timbers were cut with a whipsaw. Office in one end—sleeping room in the other—and the ‘hall’ was used for saddle, fishing tackle, etc. Hospitality was only 30c per gallon, with corn stoppers.”

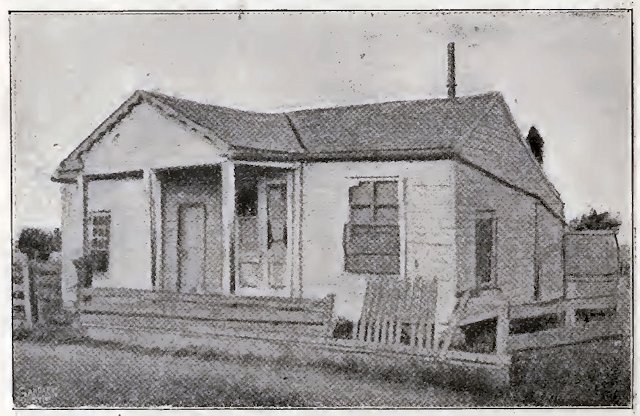

This house, which originally stood in Birdville, was Terrell’s second law office and the first bank building of Martin Bottom Loyd. (Photo from Early Days of Fort Worth.)

This house, which originally stood in Birdville, was Terrell’s second law office and the first bank building of Martin Bottom Loyd. (Photo from Early Days of Fort Worth.)

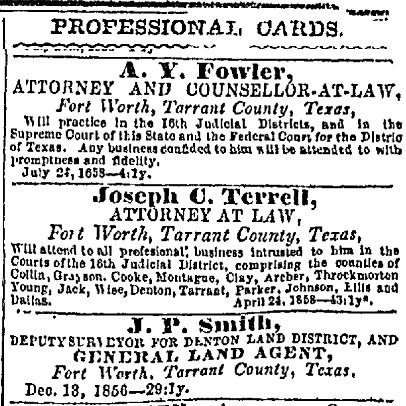

Terrell was sandwiched between A. Y. Fowler and John Peter Smith in the September 8, 1859 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Terrell was sandwiched between A. Y. Fowler and John Peter Smith in the September 8, 1859 Dallas Weekly Herald.

When the Civil War began, Terrell was opposed to secession but raised a company of men and fought for the Confederacy. After the war Terrell returned to Fort Worth to practice law for another quarter-century. He was active in Confederate veterans’ affairs.

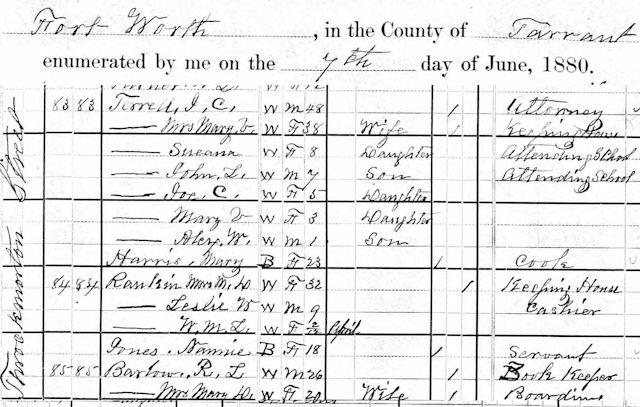

Terrell and his family lived on Throckmorton Street in 1880.

Terrell and his family lived on Throckmorton Street in 1880.

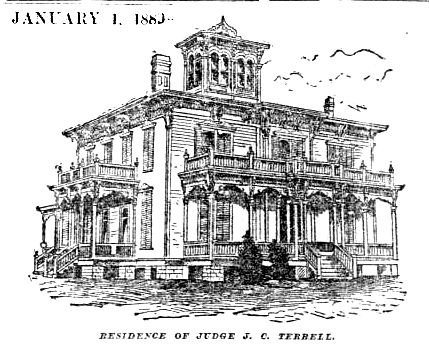

By 1881 Terrell was living in this house on Terrell Avenue. When the southern Methodist church was searching for a city in which to build its third university, Terrell recommended forty acres just north of his house. The acreage was bought, and lots on the land were sold to finance construction of the university on the remainder of the land. Five of Terrell’s children attended Fort Worth University.

By 1881 Terrell was living in this house on Terrell Avenue. When the southern Methodist church was searching for a city in which to build its third university, Terrell recommended forty acres just north of his house. The acreage was bought, and lots on the land were sold to finance construction of the university on the remainder of the land. Five of Terrell’s children attended Fort Worth University.

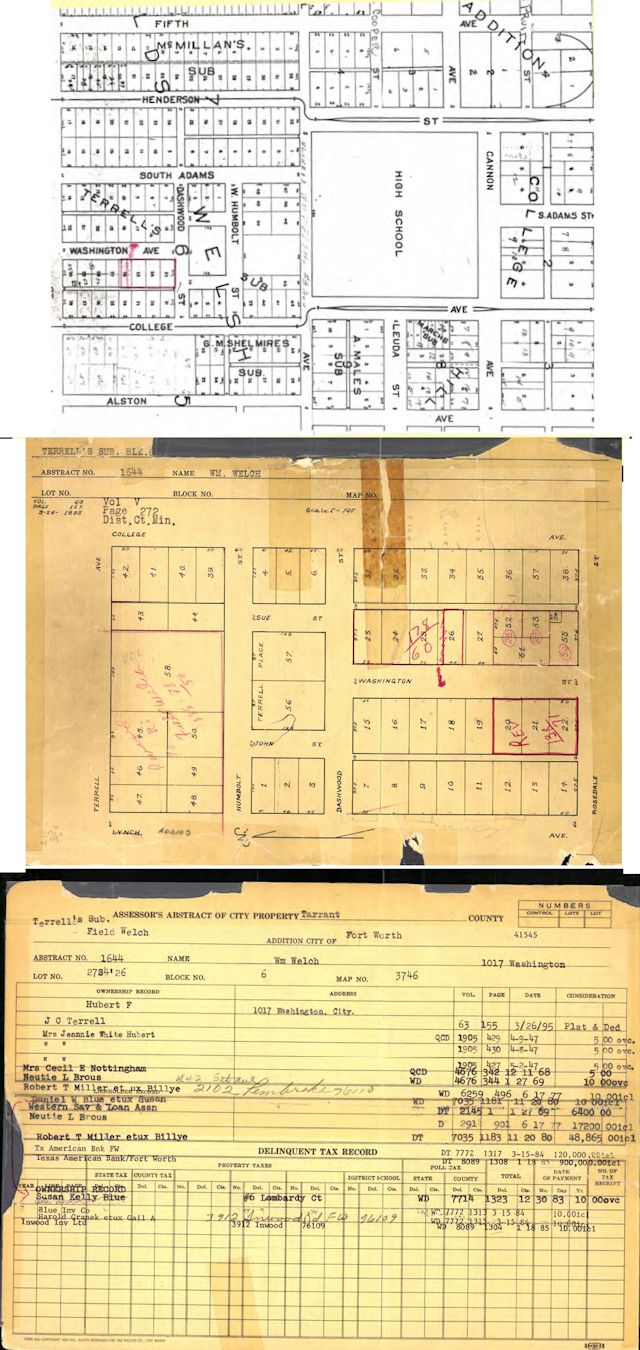

![]() The 1885 city directory lists Terrell living on his namesake street between College Avenue and Sandige Street, which became the southern extension of Henderson Street.

The 1885 city directory lists Terrell living on his namesake street between College Avenue and Sandige Street, which became the southern extension of Henderson Street.

I suspect that Terrell himself owned the land that the university was built on. Tax records show that Terrell Avenue is in Terrell’s subdivision. On the second plat (which is oriented in the opposite direction of the top plat) Terrell Place was where his house stood just south of the university. The block marked “High School” on the top plat was the site of the university. The deed card indicates that Terrell also owned some of the houses in Terrell’s subdivision.

I suspect that Terrell himself owned the land that the university was built on. Tax records show that Terrell Avenue is in Terrell’s subdivision. On the second plat (which is oriented in the opposite direction of the top plat) Terrell Place was where his house stood just south of the university. The block marked “High School” on the top plat was the site of the university. The deed card indicates that Terrell also owned some of the houses in Terrell’s subdivision.

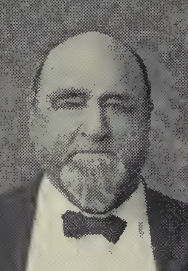

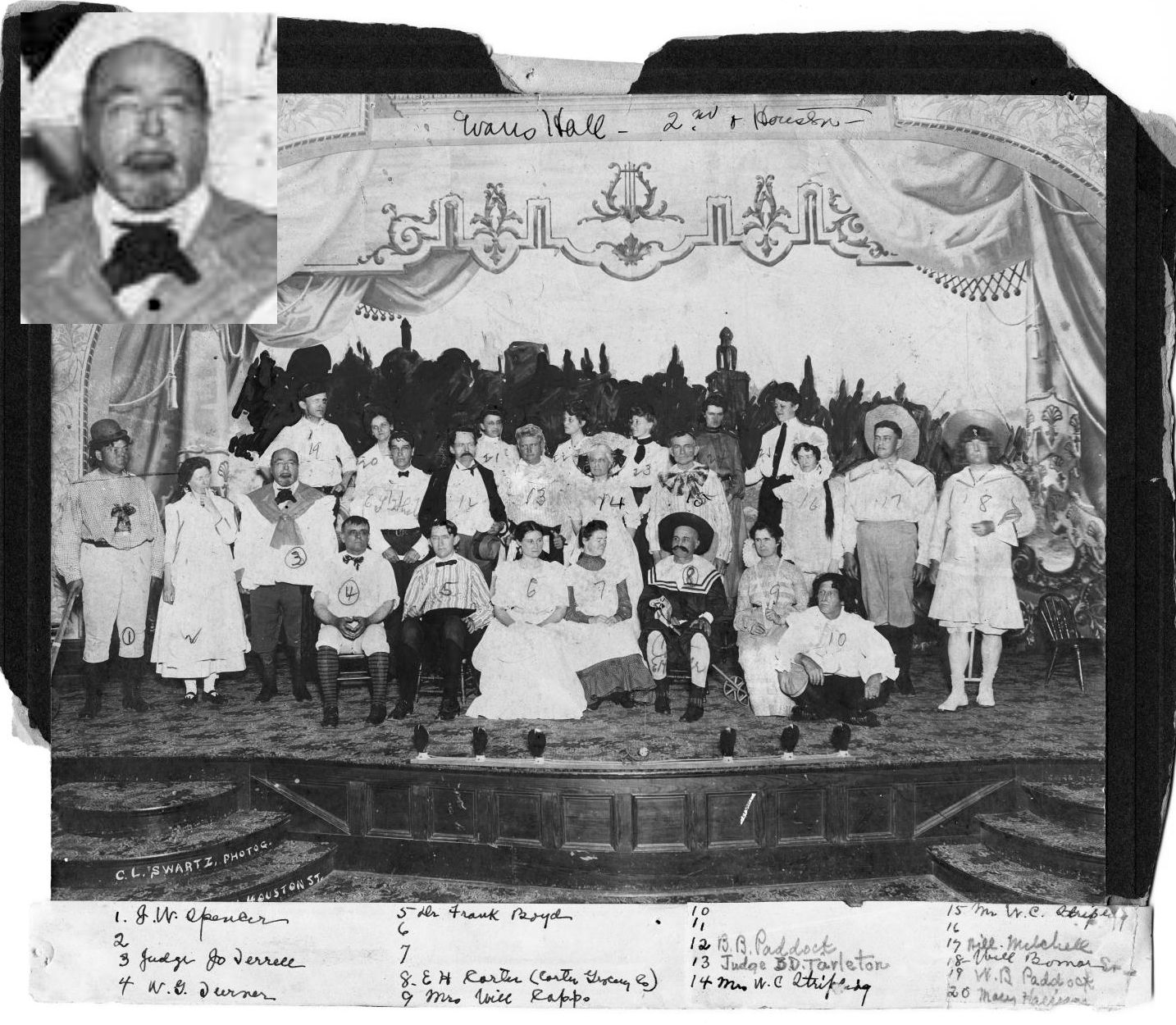

Photographer Charles Swartz took this photo of several prominent Fort Worth citizens, including Terrell, B. B. Paddock, and W. C. Stripling, in costume at Evans Hall. Inset shows Terrell. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Photographer Charles Swartz took this photo of several prominent Fort Worth citizens, including Terrell, B. B. Paddock, and W. C. Stripling, in costume at Evans Hall. Inset shows Terrell. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

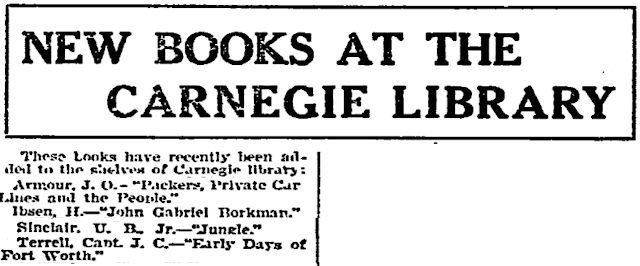

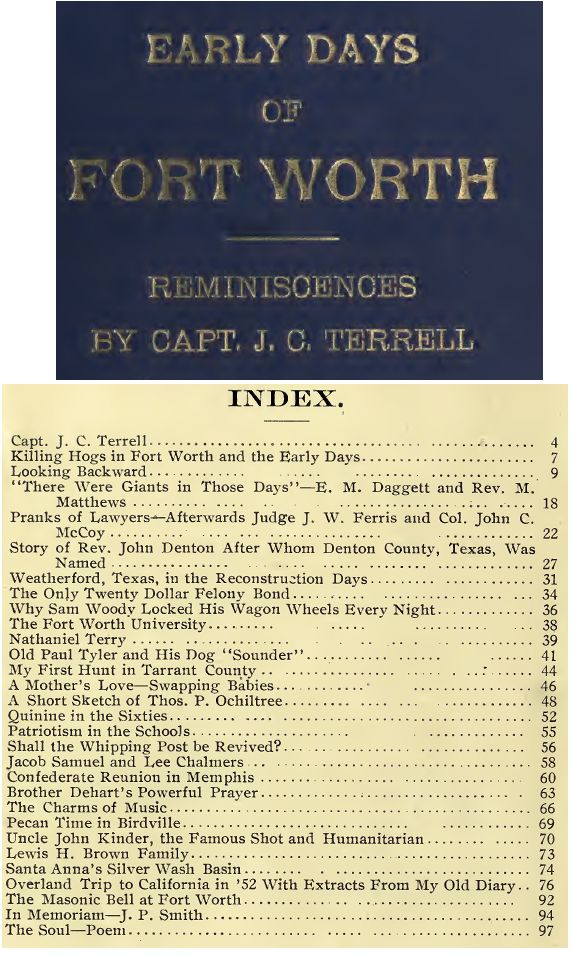

On October 7, 1906 the Telegram announced that among new books in the Carnegie Public Library was Terrell’s memoir Early Days of Fort Worth, along with works by Ibsen, Sinclair, and J. O. Armour. J. O. Armour was a son of the founder of the Armour packing plants.

On October 7, 1906 the Telegram announced that among new books in the Carnegie Public Library was Terrell’s memoir Early Days of Fort Worth, along with works by Ibsen, Sinclair, and J. O. Armour. J. O. Armour was a son of the founder of the Armour packing plants.

Here are other Hometown by Handlebar posts based on Terrell’s memoir:

“I Read from First Fallopians, Chapter 3: ‘Fret Not Thy Gizzard’”

Verbatim: Never Hotwire a Horse, Never Disrupt a Doxology

Verbatim: Well, the Bible Is a Little Black Book, Isn’t It?

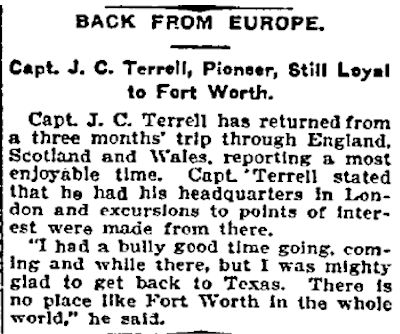

On October 8, 1909 the Star-Telegram reported that Terrell had just returned from a trip to Europe.

On October 8, 1909 the Star-Telegram reported that Terrell had just returned from a trip to Europe.

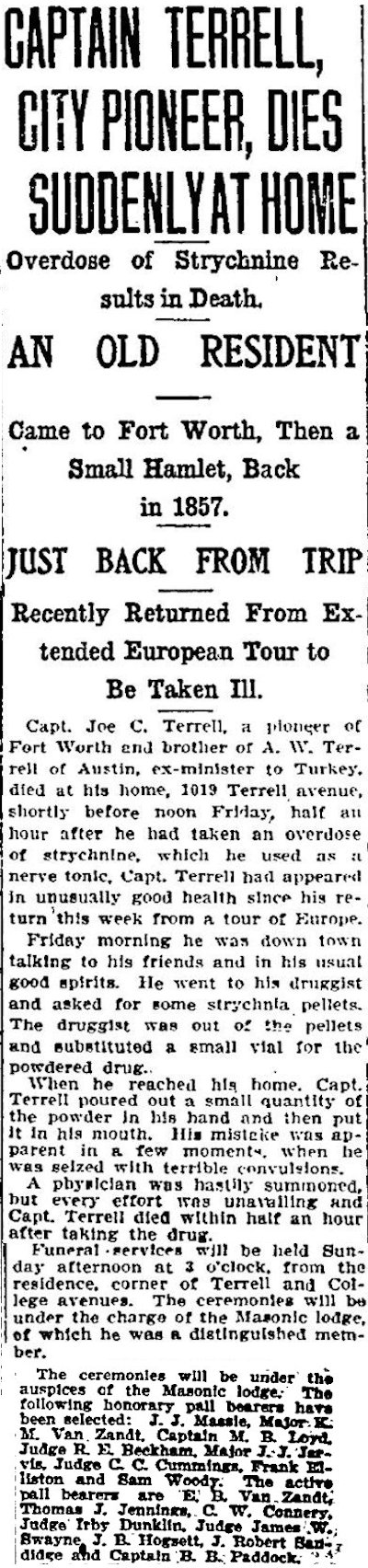

A week later Terrell died. The bottom paragraph lists his pallbearers—a veritable who’s who of early Fort Worth. Clips are from the October 15 and 16 Telegram.

A week later Terrell died. The bottom paragraph lists his pallbearers—a veritable who’s who of early Fort Worth. Clips are from the October 15 and 16 Telegram.

Joseph Christopher Terrell is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Joseph Christopher Terrell is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

I think my doxology might be out of whack or disrupted. A fellow I heard of got busted for hotwiring another fellow’s horse, got 5 to 10 in the pen.

Terrell has some great anecdotes of early Fort Worth in his book.