Scottish-born American industrialist Andrew Carnegie was an alchemist: First he turned steel into gold. A lot of gold. Then he turned gold into good works. A lot of good works: In 1886 he began to use the fortune he made in the steel industry to build public libraries in towns across the country.

Then, in 1901, when he sold Carnegie Steel Company to J. P. Morgan for $480 million ($13.6 billion today), that transaction brought Carnegie’s checking account balance to a tidy $310 billion-with-a-b in today’s dollars. That’s when Andrew Carnegie retired and really began turning gold into good works. For example, he gave away $40 million (about $1 billion today) to build more than sixteen hundred public libraries in cities across America, from sixty-seven branch libraries in New York City to thirty-two central libraries in Texas in towns from El Paso to Marshall. Of the thirty-two built in Texas, only thirteen have survived, and only four of those are still used as libraries. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Then, in 1901, when he sold Carnegie Steel Company to J. P. Morgan for $480 million ($13.6 billion today), that transaction brought Carnegie’s checking account balance to a tidy $310 billion-with-a-b in today’s dollars. That’s when Andrew Carnegie retired and really began turning gold into good works. For example, he gave away $40 million (about $1 billion today) to build more than sixteen hundred public libraries in cities across America, from sixty-seven branch libraries in New York City to thirty-two central libraries in Texas in towns from El Paso to Marshall. Of the thirty-two built in Texas, only thirteen have survived, and only four of those are still used as libraries. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Fort Worth was among those early beneficiaries of Carnegie’s philanthropy.

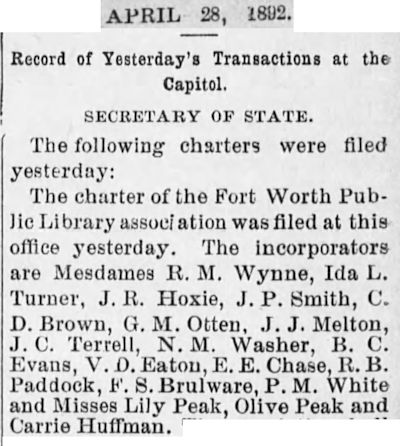

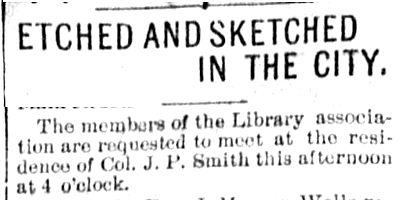

Some background: In 1892 twenty women, led by Jenny Scheuber, had formed the Fort Worth Public Library Association. But without a library building, a library association’s work is more theory than practice. Members met in private homes, such as that of John Peter Smith.

Some background: In 1892 twenty women, led by Jenny Scheuber, had formed the Fort Worth Public Library Association. But without a library building, a library association’s work is more theory than practice. Members met in private homes, such as that of John Peter Smith.

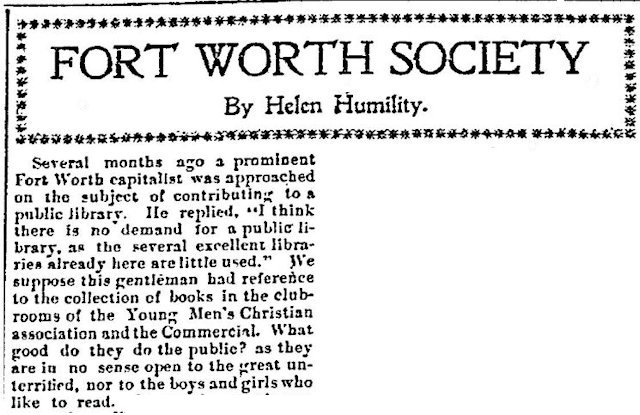

In fact, this column by “Helen Humility” in the January 10, 1897 Register indicates that some folks didn’t see much need for a public library. One prominent capitalist—a man—said the libraries at the YMCA and Commercial Club were “little used.” But those were male facilities. The Commercial Club was a men’s club that changed its name to the “Fort Worth Club” in 1906.

In fact, this column by “Helen Humility” in the January 10, 1897 Register indicates that some folks didn’t see much need for a public library. One prominent capitalist—a man—said the libraries at the YMCA and Commercial Club were “little used.” But those were male facilities. The Commercial Club was a men’s club that changed its name to the “Fort Worth Club” in 1906.

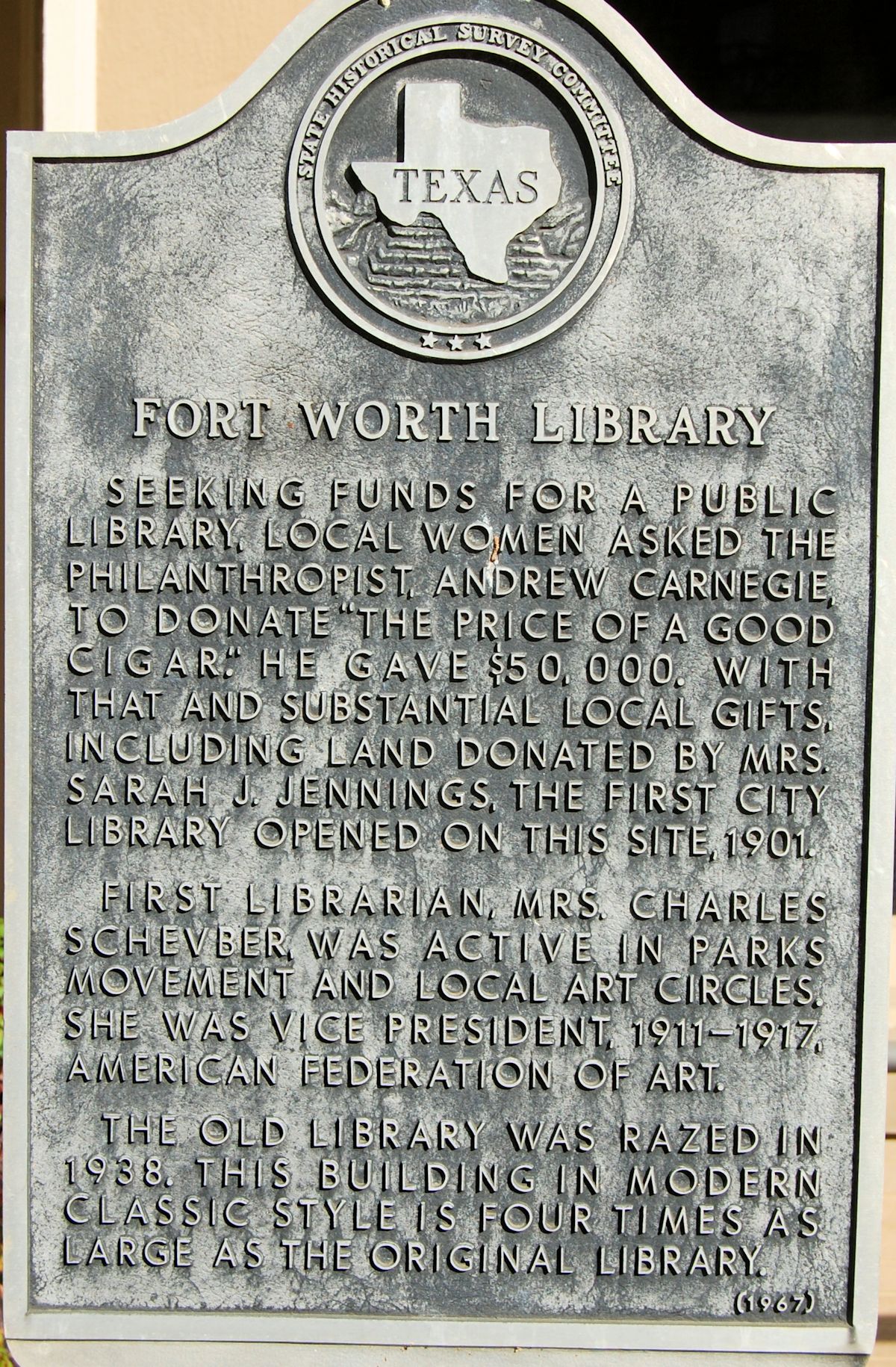

In the late 1890s the women of the library association asked for help from Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie is said to have suggested that the women ask each man in Fort Worth to donate “the price of a good cigar” to cover the cost of operating a library. When the city guaranteed $4,000 a year to operate such a library, Carnegie made his donation.

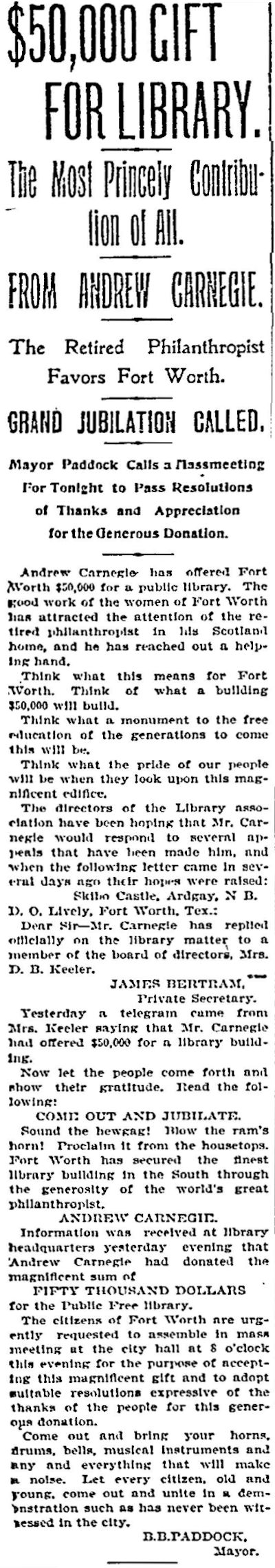

On July 26, 1899 Mayor and Cowtown head cheerleader B. B. Paddock announced that Carnegie had responded favorably to the women’s appeal: Fort Worth could receive $50,000 ($1.3 million today) to build a public library. Paddock was ecstatic: “Come out and jubilate.” “Sound the hewgag. Blow the ram’s horn. Proclaim it from the housetops!” Clip is from the Register.

On July 26, 1899 Mayor and Cowtown head cheerleader B. B. Paddock announced that Carnegie had responded favorably to the women’s appeal: Fort Worth could receive $50,000 ($1.3 million today) to build a public library. Paddock was ecstatic: “Come out and jubilate.” “Sound the hewgag. Blow the ram’s horn. Proclaim it from the housetops!” Clip is from the Register.

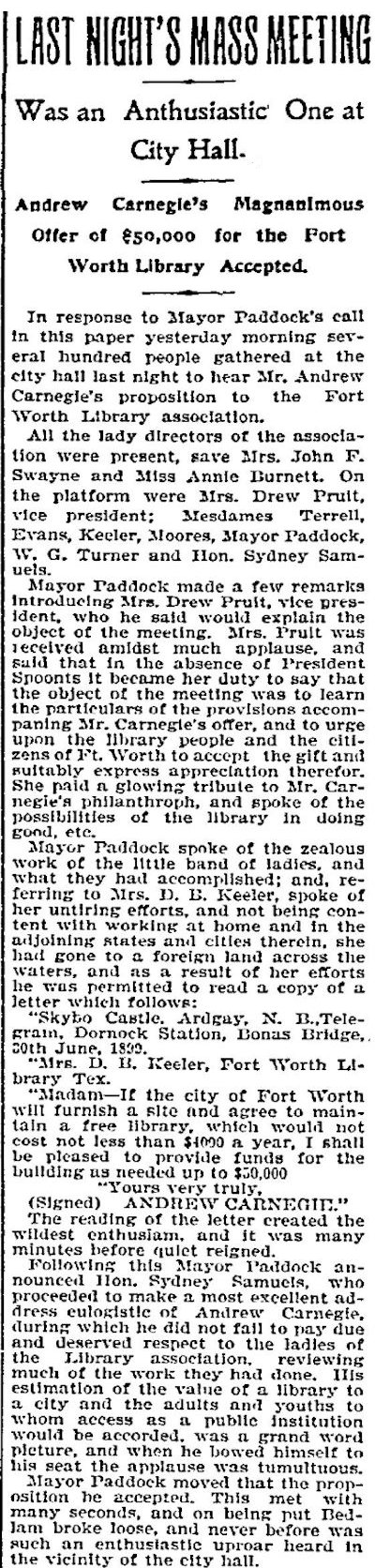

That night at a mass meeting Mayor Paddock made the motion that Carnegie’s offer be accepted. Paddock’s motion was seconded, and lo, a most unlibrary-like commotion did ensue: “Bedlam broke loose, and never before was such an enthusiastic uproar heard in the vicinity of the city hall.” Clip is from the July 27 Register.

That night at a mass meeting Mayor Paddock made the motion that Carnegie’s offer be accepted. Paddock’s motion was seconded, and lo, a most unlibrary-like commotion did ensue: “Bedlam broke loose, and never before was such an enthusiastic uproar heard in the vicinity of the city hall.” Clip is from the July 27 Register.

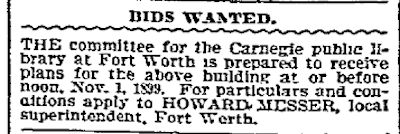

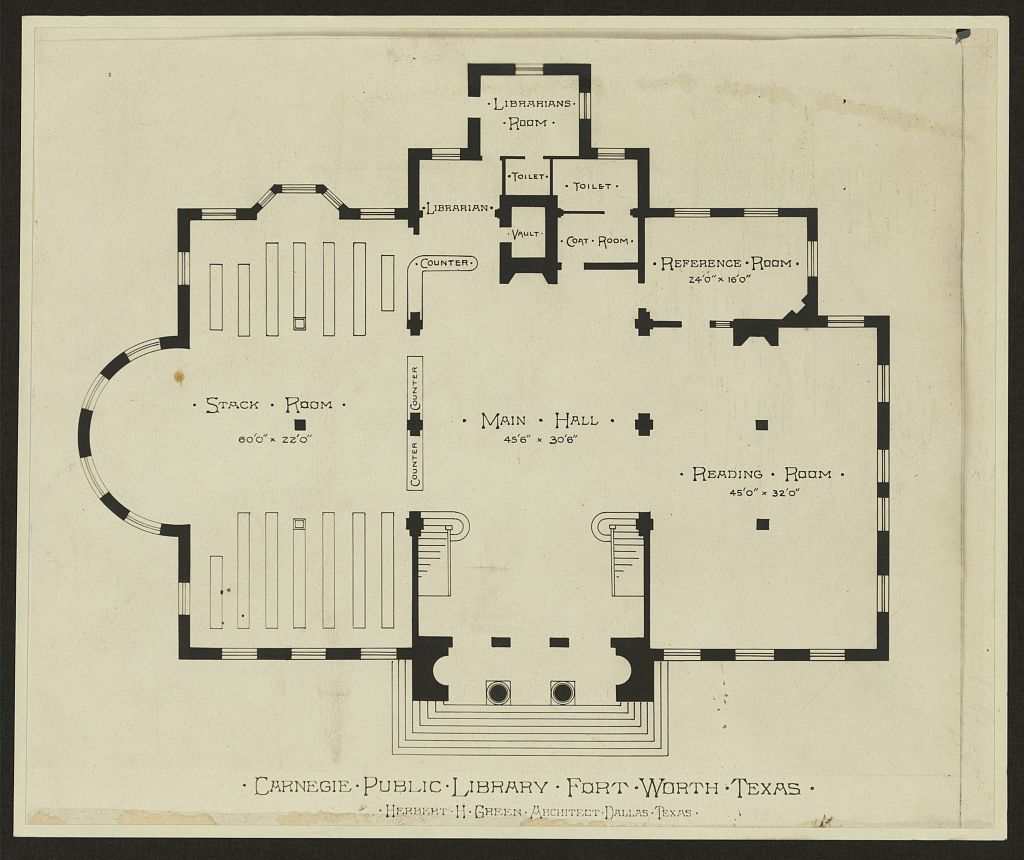

In September the city advertised for construction bids for the library building. Herbert H. Greene of Dallas was the architect. British-born architect Howard Messer was consulting architect and superintendent. Messer had designed the Ball-Eddleman-McFarland house (1899) on Penn Street. (Marshall Sanguinet designed the Carnegie libraries in Dallas and Leavenworth, Kansas.) Clip is from the September 24, 1899 Register.

In September the city advertised for construction bids for the library building. Herbert H. Greene of Dallas was the architect. British-born architect Howard Messer was consulting architect and superintendent. Messer had designed the Ball-Eddleman-McFarland house (1899) on Penn Street. (Marshall Sanguinet designed the Carnegie libraries in Dallas and Leavenworth, Kansas.) Clip is from the September 24, 1899 Register.

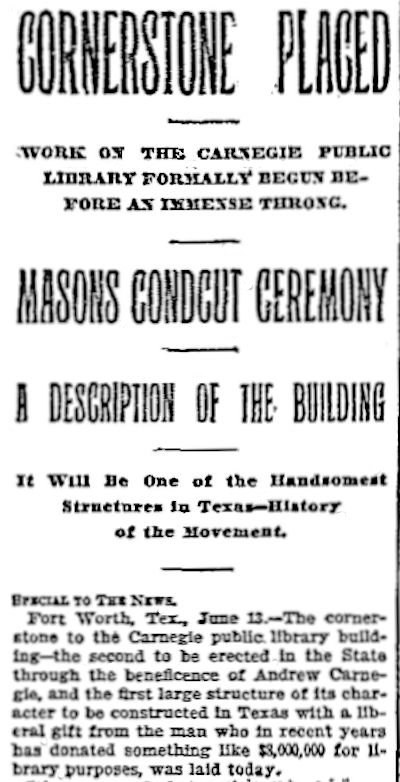

Mrs. Sarah Gray Jennings (as in the street name) donated land for the library building. She also had donated land for the city’s first park adjacent to the library in 1873. Hyde Park was named for her parents, Major John H. and Mary Gray Hyde. The cornerstone for the library was laid on June 13, 1900. This clip from the June 14 Dallas Morning News says the Fort Worth library was the second Carnegie library to be built in Texas.

Mrs. Sarah Gray Jennings (as in the street name) donated land for the library building. She also had donated land for the city’s first park adjacent to the library in 1873. Hyde Park was named for her parents, Major John H. and Mary Gray Hyde. The cornerstone for the library was laid on June 13, 1900. This clip from the June 14 Dallas Morning News says the Fort Worth library was the second Carnegie library to be built in Texas.

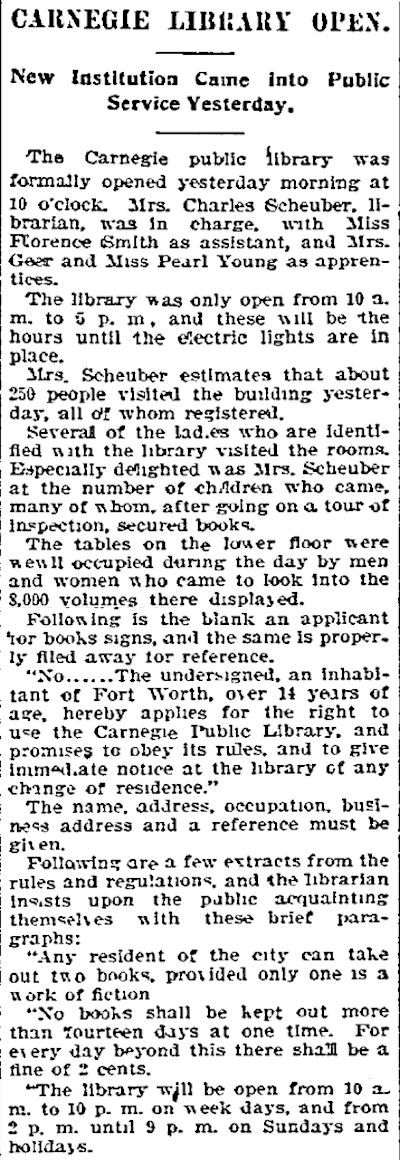

On October 17, 1901 Fort Worth’s Carnegie Public Library opened with “8,000 volumes.” The building also contained an art gallery. Jenny Scheuber of the library association served as librarian—for the next thirty-seven years. Note that the library’s operating hours were more generous than they are today. Clip is from the October 18 Register.

On October 17, 1901 Fort Worth’s Carnegie Public Library opened with “8,000 volumes.” The building also contained an art gallery. Jenny Scheuber of the library association served as librarian—for the next thirty-seven years. Note that the library’s operating hours were more generous than they are today. Clip is from the October 18 Register.

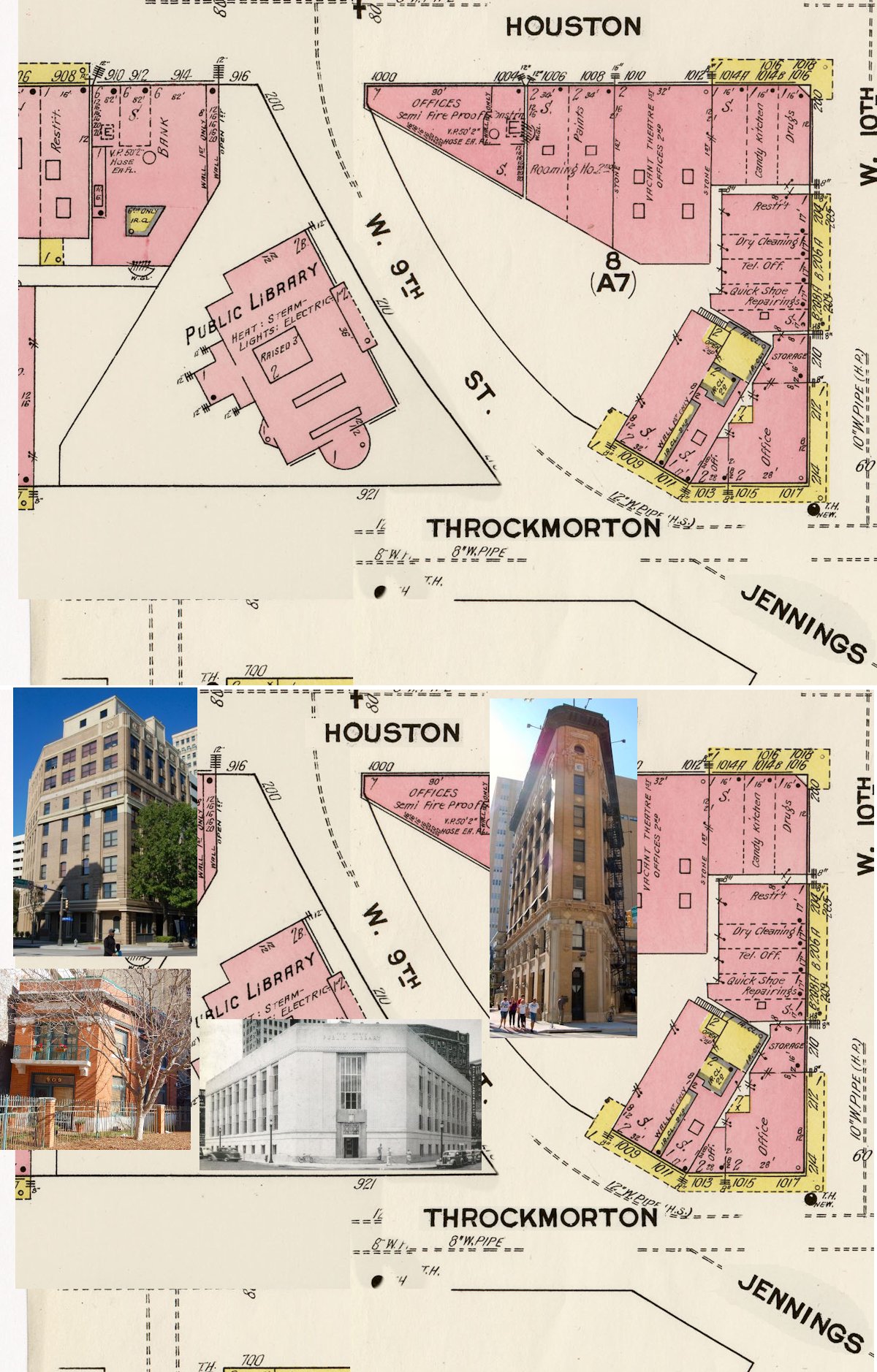

Some views of the 1901 Carnegie Public Library:

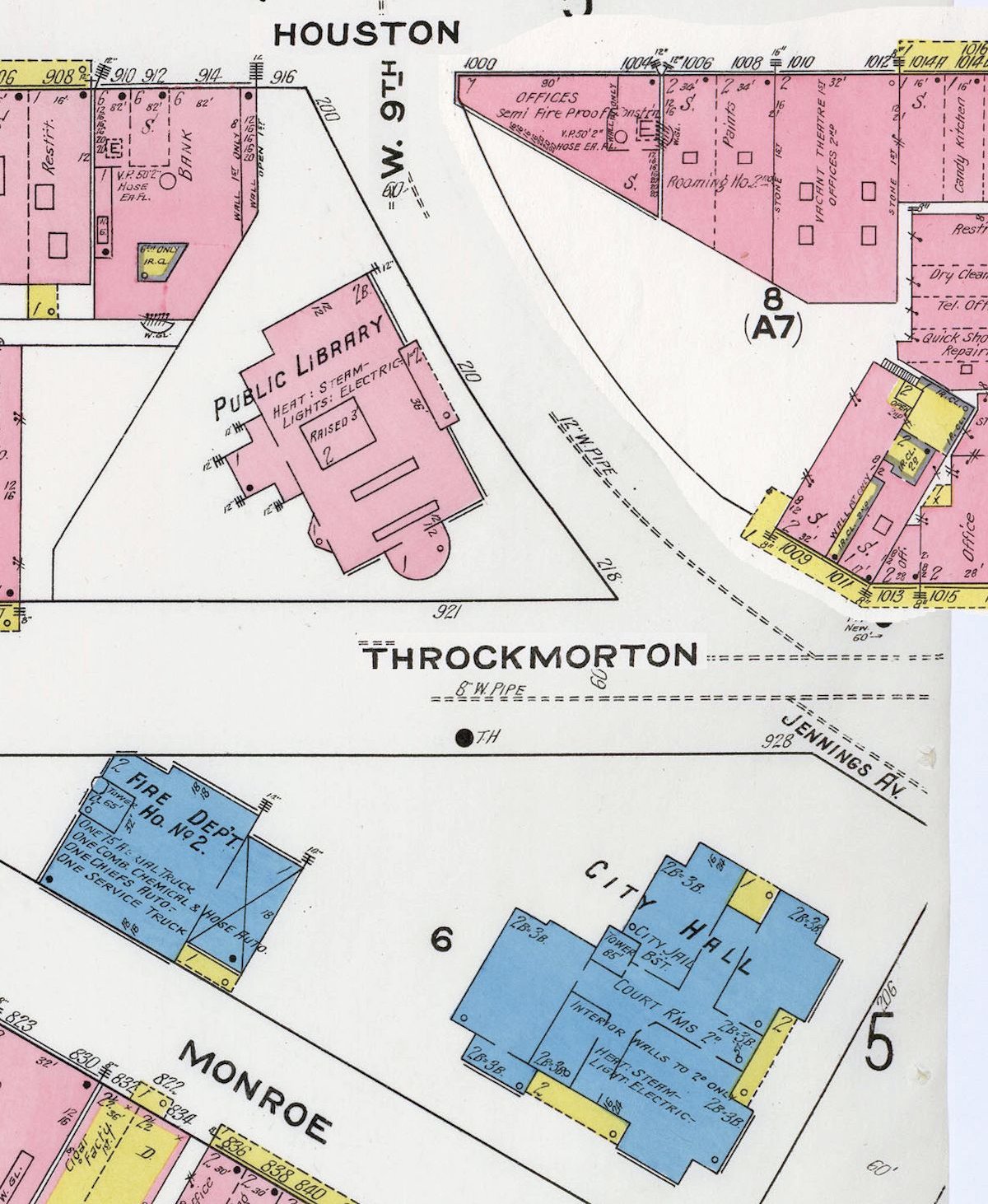

The library faced across West 9th Street toward Hyde Park and the 1907 Flatiron Building. Across Throckmorton Street were the 1893 city hall and the 1899 fire hall. (For a time in the late 1800s the library site had been a livery stable.)

The library faced across West 9th Street toward Hyde Park and the 1907 Flatiron Building. Across Throckmorton Street were the 1893 city hall and the 1899 fire hall. (For a time in the late 1800s the library site had been a livery stable.)

Photo by Fort Worth photographer Charles Swartz. (Photo from Library of Congress.)

Photo by Fort Worth photographer Charles Swartz. (Photo from Library of Congress.)

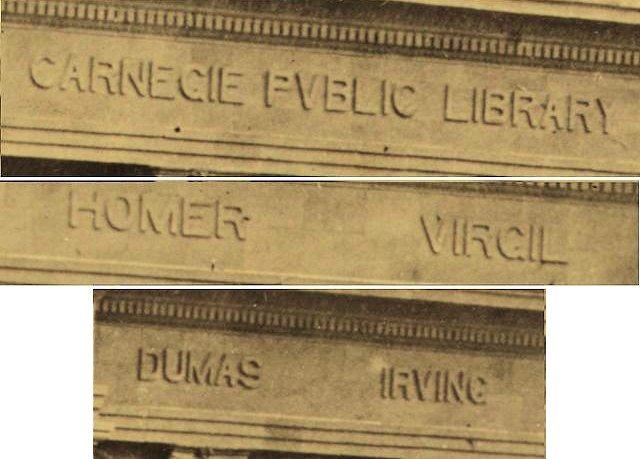

Some details of the frieze.

Some details of the frieze.

Image from Library of Congress.

Image from Library of Congress.

Under one of those top hats is President Theodore Roosevelt, possibly the gent doffing with right hand near the center of the photo (see inset). During a visit to Fort Worth in 1905 Roosevelt planted a tree at the library. Photo was taken by the ubiquitous Charles Swartz and dated April 8. Six months later, on October 6, Charles Swartz would be struck and killed by a Katy locomotive as he was taking photos. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Under one of those top hats is President Theodore Roosevelt, possibly the gent doffing with right hand near the center of the photo (see inset). During a visit to Fort Worth in 1905 Roosevelt planted a tree at the library. Photo was taken by the ubiquitous Charles Swartz and dated April 8. Six months later, on October 6, Charles Swartz would be struck and killed by a Katy locomotive as he was taking photos. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

By the mid-1930s Fort Worth needed a larger library. But a larger library would not come without a legal battle-the first of two that would bedevil Fort Worth’s libraries. Resident F. W. Rosson filed an injunction to prevent the Carnegie building from being demolished and a larger library building erected in its place, arguing that Sarah Jennings had given the land to the city to be used as a park and later gave her approval for part of the park to be used for the Carnegie library. Rosson argued that the new library building would take up the entire park in violation of the Jennings conveyance. Almost two hundred citizens signed a petition urging the city not to raze the 1901 building. The city considered building the new library in Burnett Park, but the courts ruled that Burk Burnett‘s deed conveying the park to the city prohibited its use for a library. In the end, the new library was built on the site of the old library.

Fort Worth’s 1901 Carnegie Public Library building was demolished in 1938.

Fort Worth’s 1901 Carnegie Public Library building was demolished in 1938.

The temporary home of the library was the little Atelier Building on West 8th Street (between the former sites of Thompson’s and Barber’s bookstores). The Atelier Building was built about 1905.

The temporary home of the library was the little Atelier Building on West 8th Street (between the former sites of Thompson’s and Barber’s bookstores). The Atelier Building was built about 1905.

The new library opened in June 1939.

The new library opened in June 1939.

The wedge-shaped library was designed by Joseph Pelich. The exterior was cut limestone blocks. The interior featured wood paneling, a large staircase, a card catalog, and ornate light fixtures, some of which survive in the Intermodal Transportation Center. There were booths for listening to “phonograph records.” And just as important, the library was home port for the bookmobiles.

The wedge-shaped library was designed by Joseph Pelich. The exterior was cut limestone blocks. The interior featured wood paneling, a large staircase, a card catalog, and ornate light fixtures, some of which survive in the Intermodal Transportation Center. There were booths for listening to “phonograph records.” And just as important, the library was home port for the bookmobiles.

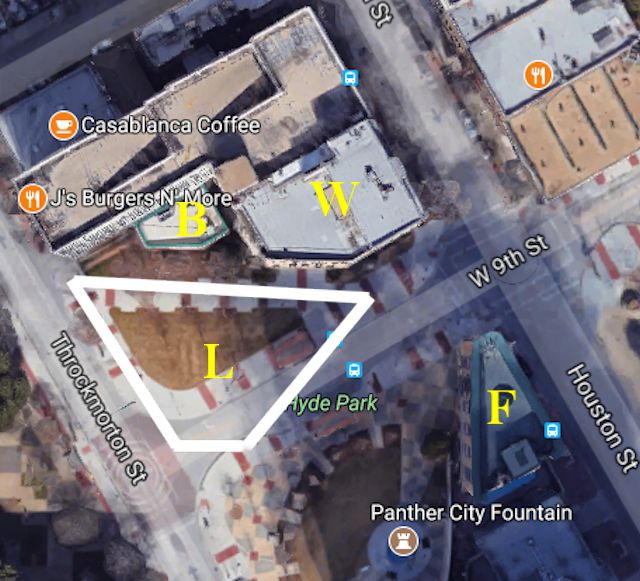

Standing at the corner of Cattywampus and Honkerjawed: But why was the 1939 library wedge shaped? Because, at least in part, until a few years ago West 9th Street did not meet Throckmorton Street at a ninety-degree angle. And originally Houston, Throckmorton, and Jennings did not intersect. Then Throckmorton was extended southeast, and West 9th (like Throckmorton, part of downtown’s dominant northwest-southeast grid) was extended in a bend to the south to meet Jennings (part of downtown’s smaller north-south grid) at Throckmorton. (Throckmorton is a junction street of the two grids.) The curved extension of West 9th to the south created a triangle, with West 9th and Throckmorton being two of the three legs. The third leg was formed by property lines that were not parallel to the adjacent streets. Thus in the immediate area were four buildings with odd shapes: the 1907 Flatiron Building on Houston at West 9th, the 1906 Western National Bank Building on Houston at West 9th, the little 1910 Bryce Building at 909 Throckmorton Street, and the 1939 library.

Standing at the corner of Cattywampus and Honkerjawed: But why was the 1939 library wedge shaped? Because, at least in part, until a few years ago West 9th Street did not meet Throckmorton Street at a ninety-degree angle. And originally Houston, Throckmorton, and Jennings did not intersect. Then Throckmorton was extended southeast, and West 9th (like Throckmorton, part of downtown’s dominant northwest-southeast grid) was extended in a bend to the south to meet Jennings (part of downtown’s smaller north-south grid) at Throckmorton. (Throckmorton is a junction street of the two grids.) The curved extension of West 9th to the south created a triangle, with West 9th and Throckmorton being two of the three legs. The third leg was formed by property lines that were not parallel to the adjacent streets. Thus in the immediate area were four buildings with odd shapes: the 1907 Flatiron Building on Houston at West 9th, the 1906 Western National Bank Building on Houston at West 9th, the little 1910 Bryce Building at 909 Throckmorton Street, and the 1939 library.

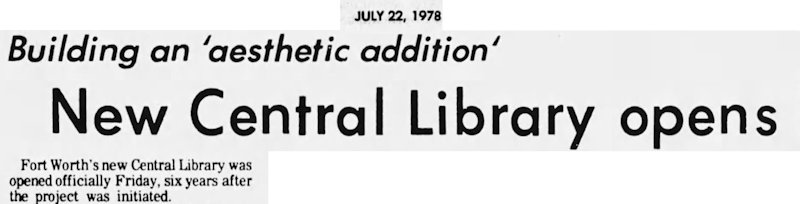

Fast-forward to 1978. Fort Worth again needed a larger library. The current central library on West 3rd Street opened.

Fast-forward to 1978. Fort Worth again needed a larger library. The current central library on West 3rd Street opened.

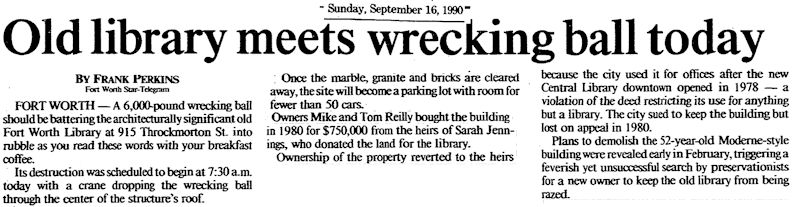

The 1939 wedge-shaped library building survived. For a while. Cue the second legal battle. The 1939 library was demolished in 1990 after ownership of the property reverted to the heirs of Sarah Jennings because the city had violated a deed restriction on use of the building. The city fought the reversion in court but lost. The Jennings family sold the property. The new owners demolished the building.

The Carnegie cornerstone stands on the site of the 1939 library. Officers and directors included Paddock and the wives of J. C. Terrell, B. C. Evans, B. C. Rhome, Samuel Burk Burnett, and Winfield Scott.

The Carnegie cornerstone stands on the site of the 1939 library. Officers and directors included Paddock and the wives of J. C. Terrell, B. C. Evans, B. C. Rhome, Samuel Burk Burnett, and Winfield Scott.

Note that the historical marker on the site was placed when the 1939 library still stood.

Note that the historical marker on the site was placed when the 1939 library still stood.

Oh, and a hewgag is a toy musical pipe.

I graduated from Heights in 1966 with a Mike Reilly. He’s now a big real estate mogul in Arlington. I wonder if that’s the same Mike Reilly who with brother Tom bought the building in 1980 for $750,000?

Dan, a quick check of newspaper archives suggests that to be the case. I can e-mail you clips showing that Mike and Tom Reilly were part of Ryan Mortgage, which “managed” the library property for “Canadian owners.”

Do you happen to have, or know where I can find, photographs of the art gallery in of the old Carnegie Library? I’m trying to tie down a story for a friend about some art that may (or may not) have been part of the Carnegie collection…

Side note: Just found the blog because of this entry. I’ll be reading a bit; keep up the good work. I’ll see you on the street somewhere.

Thanks. I don’t think I have seen any photos of the interior of the library. The FW public library might be the best bet.

Looks like the tree Roosevelt planted is gone too.

Assuming it was cut down to make way for the next library, I wonder if the people who cut it down were even aware of its presidential pedigree.

Do you know if the Carnegie 1900 cornerstone still resides at the location mentioned above? If it’s not there anymore, do you know where it is now? Enjoy your site so much! Thank you!

Thanks, Pam. Google street view of January shows the cornerstone and the historical marker still there.

Thanks, Mike, Mr. Carnegie, and all the men who gave up their smokes. And, of course, the nice ladies. A time when Fort Worthians built, not destroyed. Knowledge means power, power is might. Might makes right.

Thanks, Earl. Until 1930 and later, you could stand where the panther fountain is today and see, within three blocks, the 1896 Federal Building/Post Office, 1893 City Hall, 1899 Central Fire Station, and 1901 Carnegie Public Library. I’ll have a post soon on these and other downtown casualties.

I had no idea so few Carnegie libraries were left in Texas. My family lived in Cleburne for a little more than a year, 1958-59. The little Carnegie library was within easy walking distance, and I walked ii several times a week. What a luxury, for a Poly girl who had never ever had access to such a wealth of books. The Cleburne library was, and is, a graceful little classical building, preserved now as a city museum.

We don’t let dust collect on our wrecking ball around here. Shame to lose that grand little building. It took up so little space.

Working downtown on the 800 block of Taylor from 1975 to 2000, I often recalled the too few hours I was in that library while it still stood. I could not walk across the parking lot that replaced it without walking down memory lane

. Thanks for the history of the building Mike.

Thanks, Ramiro. Two buildings of vastly different architecture. Wish we still had them both.

I grew up in T.C.U. on Greene Ave. Was that street named for Herbert H.Greene?

Candace, my guess is that Greene Street is named after someone affiliated with TCU, as are Waits and Cockrell streets on each side of Greene Street. The architect Greene lived and worked in Dallas.