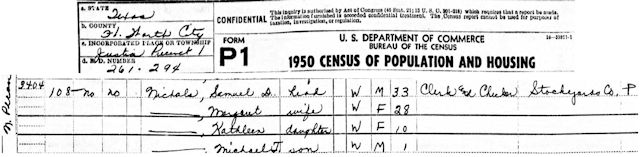

This year the federal government released the 1950 census (there is a seventy-two-year embargo on censuses).

For many of us, the 1950 federal nose count is the first that includes our own nose. My family was living on North Pecan Street near the stockyards before moving to Poly in 1951.

Fast-backward a century. On October 31, 1850 William Hogan saddled up his horse and rode off to count noses. In the next week he would travel many a mile to find noses to count. Some of those noses were located below eyes that no doubt narrowed in suspicion at the stranger who knocked on the doors of isolated cabins to ask folks a lot of tomfool personal questions.

Fast-backward a century. On October 31, 1850 William Hogan saddled up his horse and rode off to count noses. In the next week he would travel many a mile to find noses to count. Some of those noses were located below eyes that no doubt narrowed in suspicion at the stranger who knocked on the doors of isolated cabins to ask folks a lot of tomfool personal questions.

William Hogan was Tarrant County’s first census-taker.

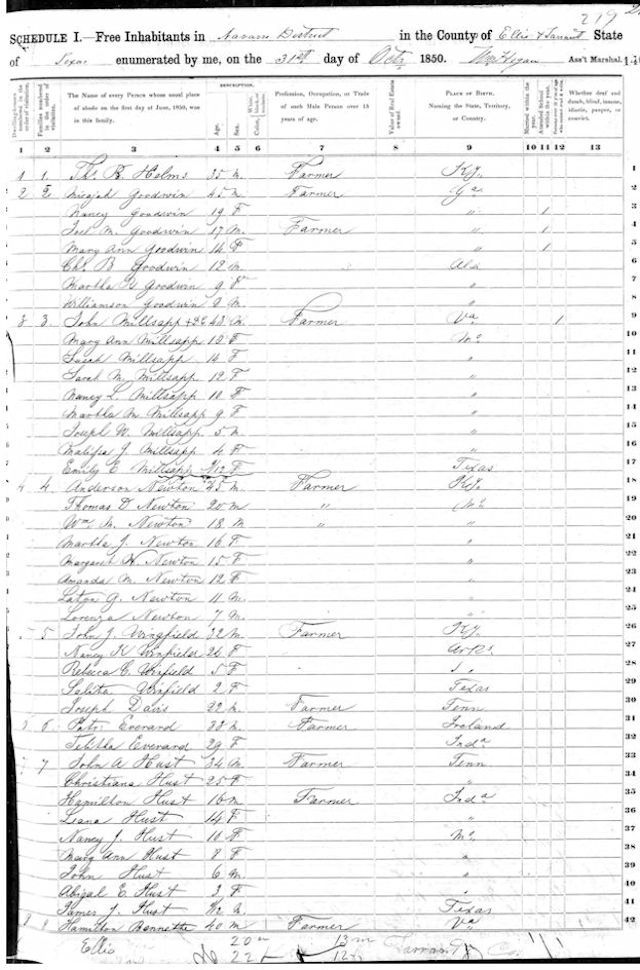

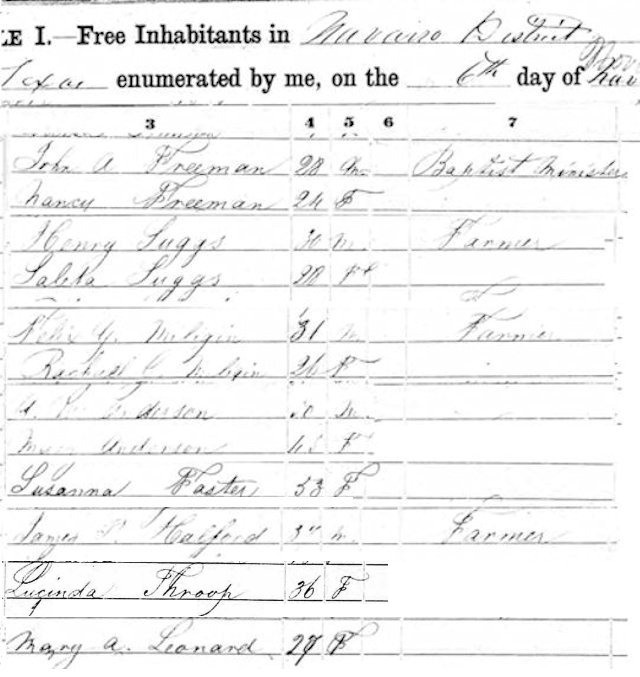

The Tarrant County census of 1850 may look like just sixteen pages of names and numbers. But that census is unique for two reasons: It was the first for the new county, and it was the only census that included the Army’s Fort Worth.

The Tarrant County census of 1850 may look like just sixteen pages of names and numbers. But that census is unique for two reasons: It was the first for the new county, and it was the only census that included the Army’s Fort Worth.

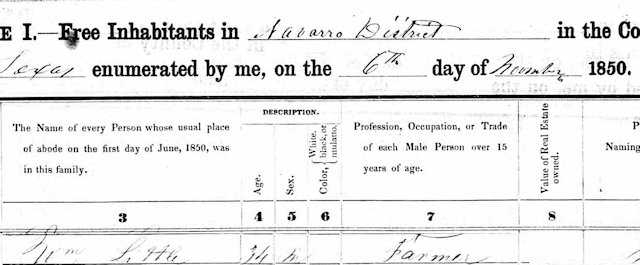

William Hogan, carrying his census forms and writing supplies in his saddlebags, spent October 31-November 6 canvassing Tarrant County and part of Ellis County, guiding his horse along the few rudimentary trails he could find as he went from door to door. And those doors, like the noses behind them, were few and far between in 1850. The settlements were as rare as the trails. A settlement had begun at present-day Grapevine in 1845, at Johnson Station in 1847, and at Birdville in 1848. After 1849 migrants had gradually begun to settle near the new military fort at the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River. “Oldtimers” had been in the area all of five years. No adults in the census had been born in Texas.

Census-takers were instructed to “approach every family and individual from whom he solicits information with civil and conciliatory manners, and adapt himself, as far as practicable, to the circumstances of each, to secure confidence and good will, as a means of obtaining the desired information with accuracy and dispatch.”

Census-takers had to provide their own ink, blotting paper, and pens.

William Hogan’s census enumerated 672 “free inhabitants” (soldiers and civilians) in the county’s 897 square miles. Hogan counted 558 civilians but only ninety homes—6.2 members per household. There were only ninety-five taxpayers in the county. They paid, historian Julia Kathryn Garrett writes, a total of $80 ($2,400 today) in taxes.

For comparison, 672 people in 897 square miles is a density of .75 person—not even a whole person—per square mile or 1.3 square miles per person. In 2020 Tarrant County’s population was estimated at 2.1 million. That is a density of 2,341 people per square mile (.00042 square mile or 11,708 square feet—a square 109 feet on a side—per person).

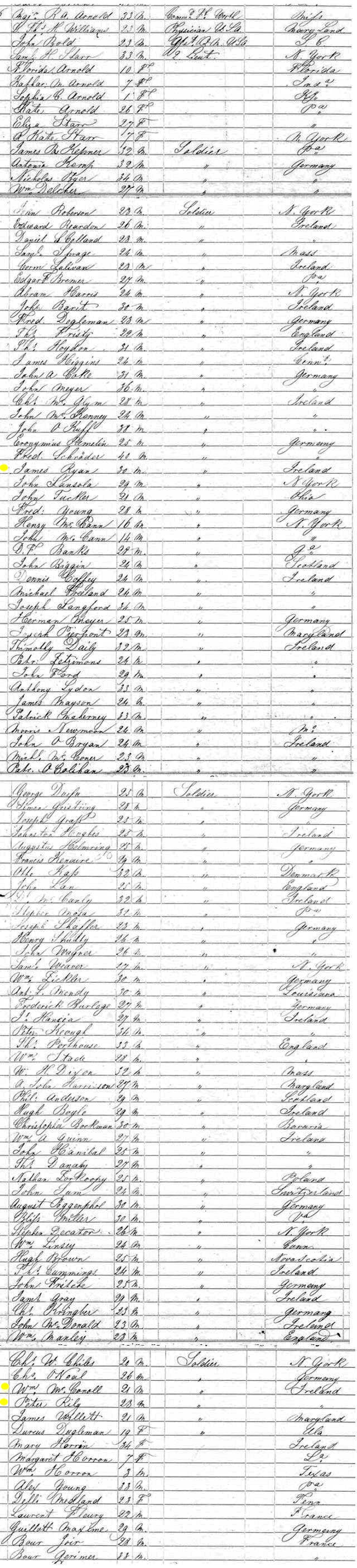

The fort easily contained the county’s greatest concentration of people. Census-taker Hogan spent November 4 at the fort, enumerating 103 soldiers—including Major Ripley Allen Arnold, a camp physician, and two lieutenants—and eleven women and children. Seventy-four of the 103 soldiers were born in foreign countries: England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Denmark, Poland, Switzerland, Germany, France.

The fort easily contained the county’s greatest concentration of people. Census-taker Hogan spent November 4 at the fort, enumerating 103 soldiers—including Major Ripley Allen Arnold, a camp physician, and two lieutenants—and eleven women and children. Seventy-four of the 103 soldiers were born in foreign countries: England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Denmark, Poland, Switzerland, Germany, France.

The oldest soldier was forty, the youngest fourteen. Average age: twenty-seven.

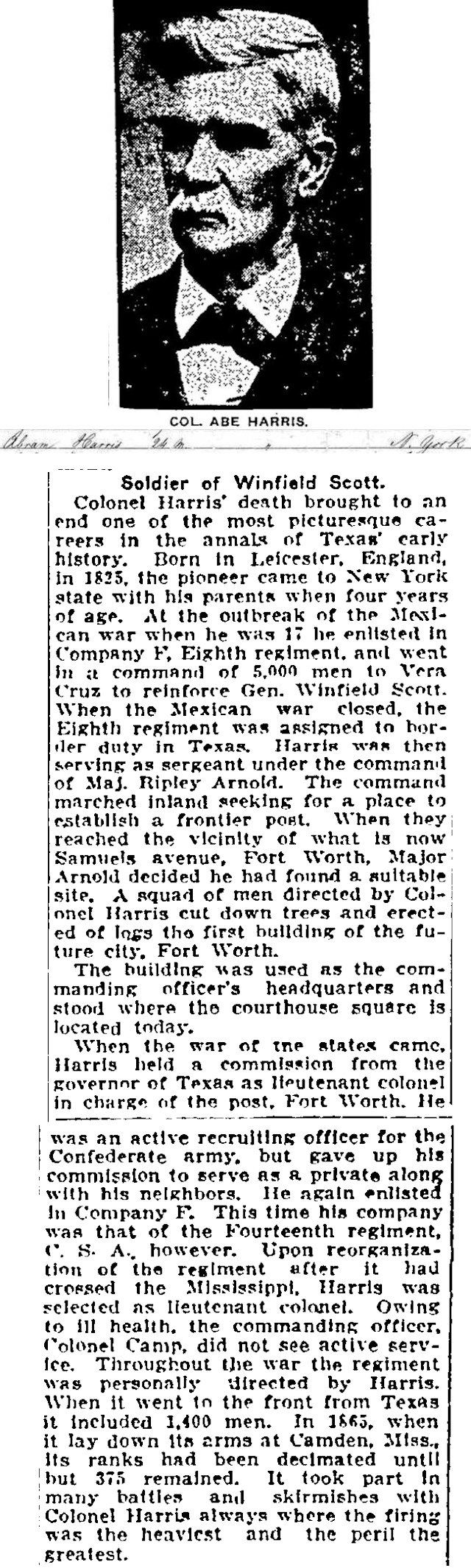

The fort had been established in 1849 along the western frontier as the so-called Indian Wars continued. The Indian Wars were the middle war for some of these young soldiers, such as Abe Harris, age twenty-four, from New York. These men had earlier fought in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and would later fight in the Civil War. Harris would survive all three wars and die in Fort Worth at age eighty-nine. Harris, a carpenter, is said to have built the fort’s first building. When he died in 1915 he was thought to be the last surviving soldier of the fort. Clips are from the December 12, 1909 and March 29, 1915 Star-Telegram

The fort had been established in 1849 along the western frontier as the so-called Indian Wars continued. The Indian Wars were the middle war for some of these young soldiers, such as Abe Harris, age twenty-four, from New York. These men had earlier fought in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and would later fight in the Civil War. Harris would survive all three wars and die in Fort Worth at age eighty-nine. Harris, a carpenter, is said to have built the fort’s first building. When he died in 1915 he was thought to be the last surviving soldier of the fort. Clips are from the December 12, 1909 and March 29, 1915 Star-Telegram

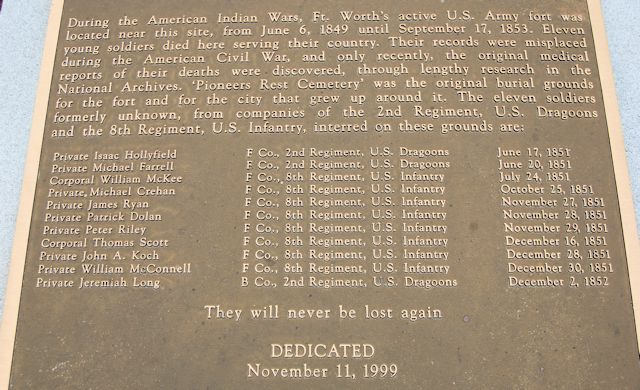

Of the fort’s soldiers in 1850, privates William McConnell, Peter Riley, and James Ryan (see yellow dots in census list), all from Ireland, would die in the next two years. They are buried at Pioneers Rest Cemetery along with eight other soldiers of the fort.

Of the fort’s soldiers in 1850, privates William McConnell, Peter Riley, and James Ryan (see yellow dots in census list), all from Ireland, would die in the next two years. They are buried at Pioneers Rest Cemetery along with eight other soldiers of the fort.

Outside the fort those 558 “free inhabitants” were scattered over the county’s 897 square miles. That’s a lot of elbow room (which was the lure for many of these settlers). Some settlers had land grants, such as from Peters Colony; some were squatters.

By our standards of living today, these from-the-git-goers were roughing it. Transportation was a horse or a pair of feet. Communication was a shout. Illumination was a candle or a lantern. Heat was a wood fire. A water fountain was the river, a spring, or a well dug in limestone. The county had a handful of “merchants,” but for the most part people shopped for groceries with a rifle and a hoe.

They lived in one-room cabins made of logs hewn by hand. If a cabin had windows, there certainly was no glass in them. No nails, no lumber, no paint, no concrete, no bricks.

Plenty of nothin’.

Running water, indoor plumbing, refrigeration, electricity, gas heat, paved roads were decades away.

Predictably, the census shows, the vast majority of the adult male settlers were farmers, with a wheelwright, two blacksmiths, two physicians, two saddlers, a carpenter, a Baptist minister, and a school teacher mixed in.

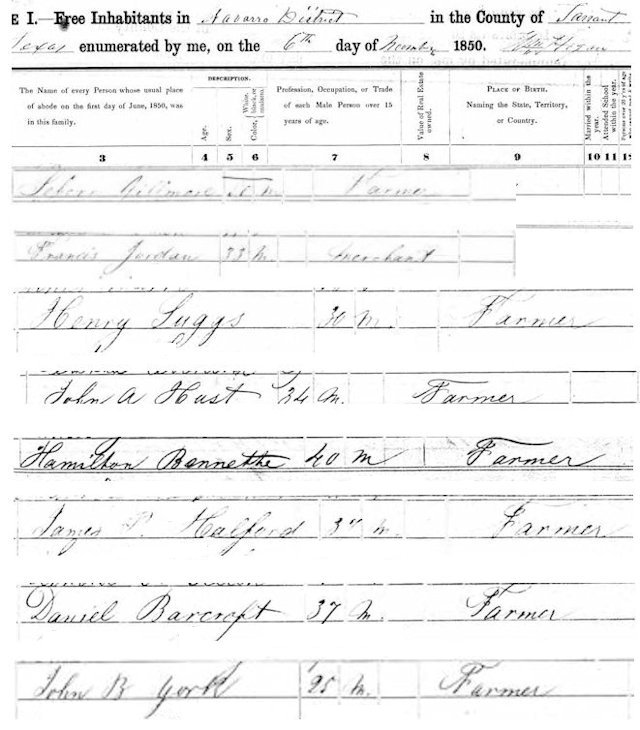

![]() But several of those farmers had a second job. The new county had held its first election in August. Enumerated among the settlers (shown above):

But several of those farmers had a second job. The new county had held its first election in August. Enumerated among the settlers (shown above):

Farmer Seaborne Gilmore, elected Tarrant County’s first county judge.

Merchant Francis Jordan, first sheriff.

Farmer John A. Hust, first county tax assessor.

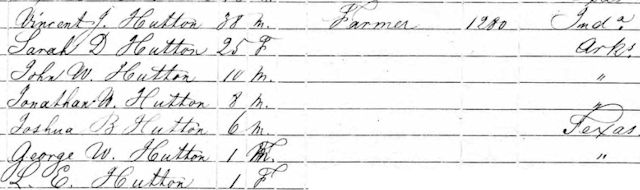

(Some sources say that the first county tax assessor was Reverend Vincent James Hutton, a Baptist preacher who kept his pistols handy when behind the pulpit, and that Hutton resigned after four months and was replaced by Hust.)

(Some sources say that the first county tax assessor was Reverend Vincent James Hutton, a Baptist preacher who kept his pistols handy when behind the pulpit, and that Hutton resigned after four months and was replaced by Hust.)

Farmer Henry Suggs, first county treasurer.

Farmers Hamilton Bennett, James P. Halford, and Daniel Barcroft were three of the four first county commissioners.

Farmer John B. York in 1852 would be elected Tarrant County’s second sheriff. In 1861 York would be killed in a confrontation with attorney Archibald Young Fowler.

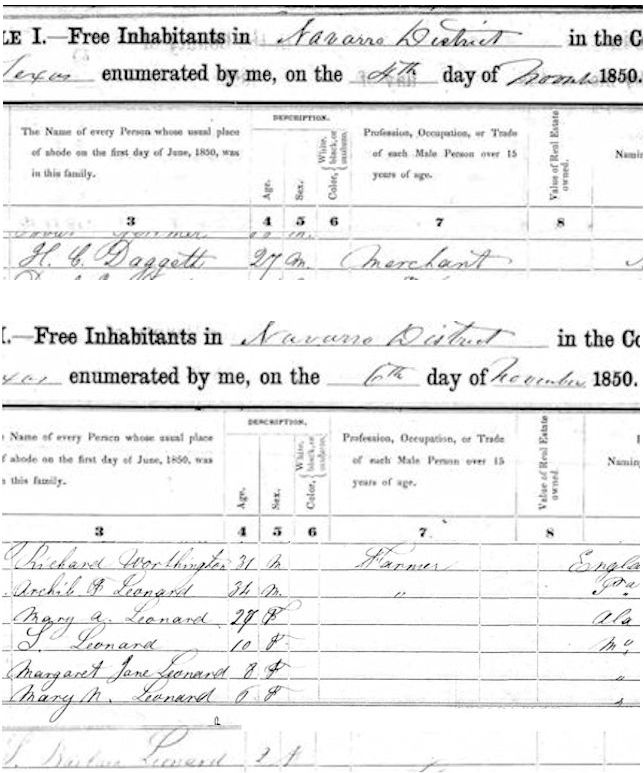

According to a historical marker at his grave in Birdville Cemetery, Archibald Franklin Leonard was the first county clerk. Garrett says Benjamin Patton Ayres was the first county clerk.

Like census-taker Hogan, these county officials performed their duties on horseback over considerable distances.

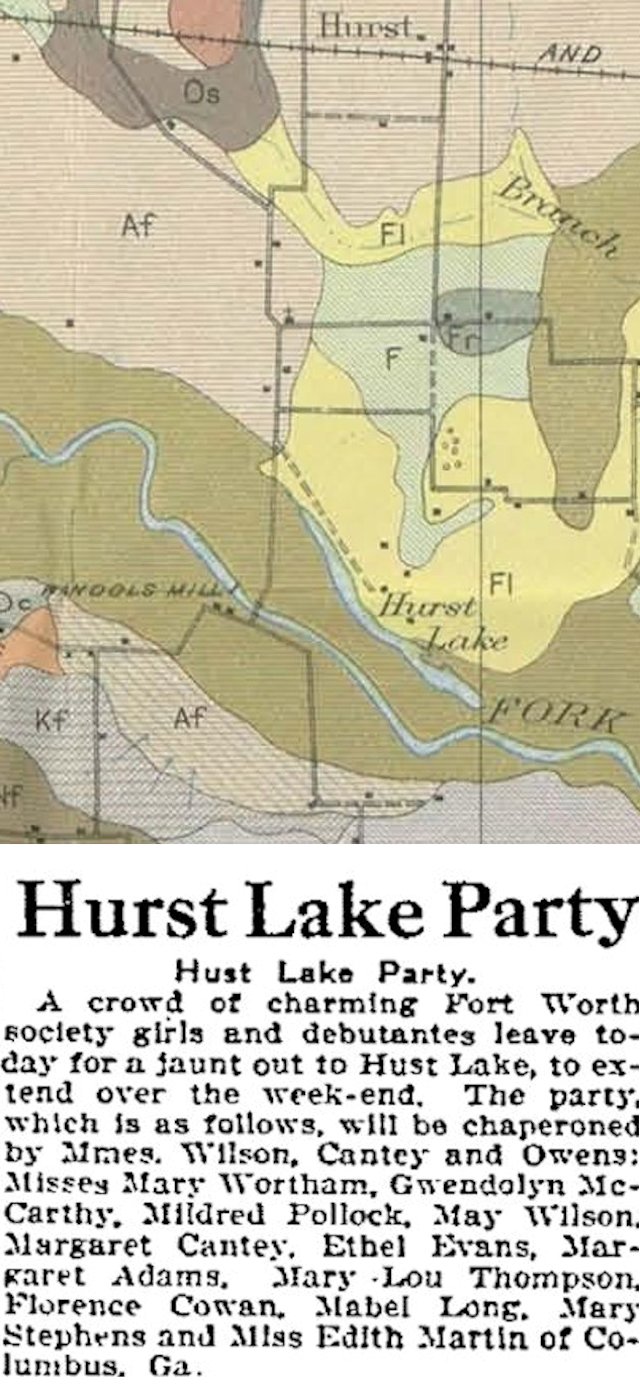

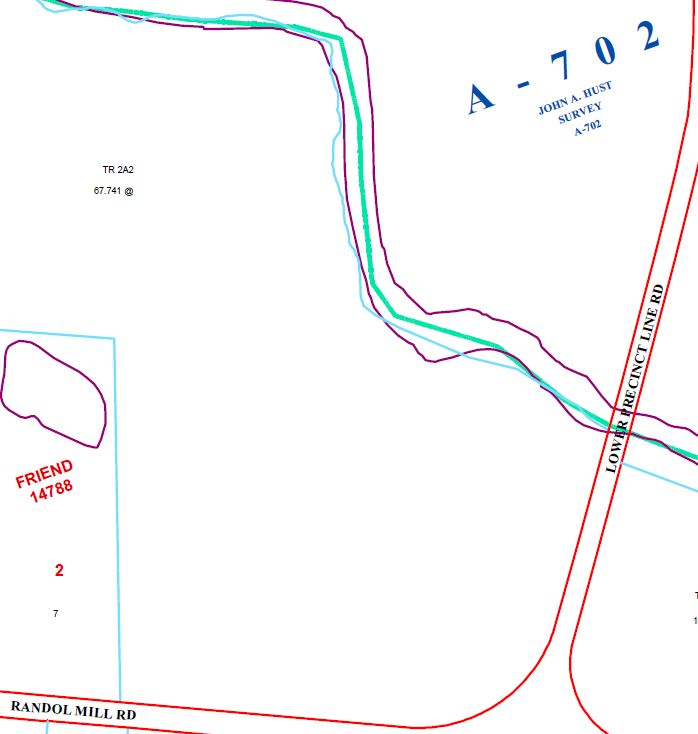

Farmer and tax assessor John A. Hust lived nine miles east of the fort and just north of the river near today’s intersection of Randol Mill Road and Precinct Line Road—several miles from his office—if he had one—at the county seat of Birdville. In 1887 a small lake was impounded on his land just east of Precinct Line Road. Well into the twentieth century Hust Lake was a popular recreational area. Hust Lake was often mislabeled “Hurst Lake” because of the proximity of the lake to the town of Hurst and to the home of town namesake William Letchworth Hurst. (In 1931 the Star-Telegram wrote that the lake was on the land of John A. Hust.)

Farmer and tax assessor John A. Hust lived nine miles east of the fort and just north of the river near today’s intersection of Randol Mill Road and Precinct Line Road—several miles from his office—if he had one—at the county seat of Birdville. In 1887 a small lake was impounded on his land just east of Precinct Line Road. Well into the twentieth century Hust Lake was a popular recreational area. Hust Lake was often mislabeled “Hurst Lake” because of the proximity of the lake to the town of Hurst and to the home of town namesake William Letchworth Hurst. (In 1931 the Star-Telegram wrote that the lake was on the land of John A. Hust.)

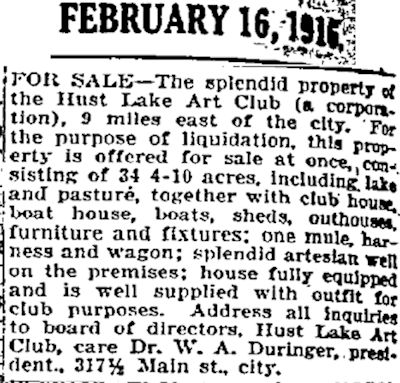

Dr. William A. Duringer was president of the Hust Lake Art Club, which owned the lake and its facilities. Apparently the property was sold in 1916.

Dr. William A. Duringer was president of the Hust Lake Art Club, which owned the lake and its facilities. Apparently the property was sold in 1916.

Today what is left of Hust Lake is a swamp surrounded by gravel quarries and gas wells. In 1856 Archibald Franklin Leonard would dam the Trinity River near Hust Lake and build a grist mill, which would eventually be owned by Robert Randol. Clip is from the May 6, 1909 Star-Telegram; 1920 USDA map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”

Hust’s land is still labeled “John A. Hust Survey” on Tarrant Appraisal District maps.

Hust’s land is still labeled “John A. Hust Survey” on Tarrant Appraisal District maps.

Henry Clay Daggett, merchant, was a brother of Ephraim Merrell Daggett. Henry Clay Daggett, historian Garrett writes, had ridden with Middleton Tate Johnson and Ripley Arnold when they selected the location for the new fort in 1849. That year Daggett and Archibald Leonard operated a small store selling staples at Traders Oak in today’s Samuels Avenue neighborhood.

Henry Clay Daggett, merchant, was a brother of Ephraim Merrell Daggett. Henry Clay Daggett, historian Garrett writes, had ridden with Middleton Tate Johnson and Ripley Arnold when they selected the location for the new fort in 1849. That year Daggett and Archibald Leonard operated a small store selling staples at Traders Oak in today’s Samuels Avenue neighborhood.

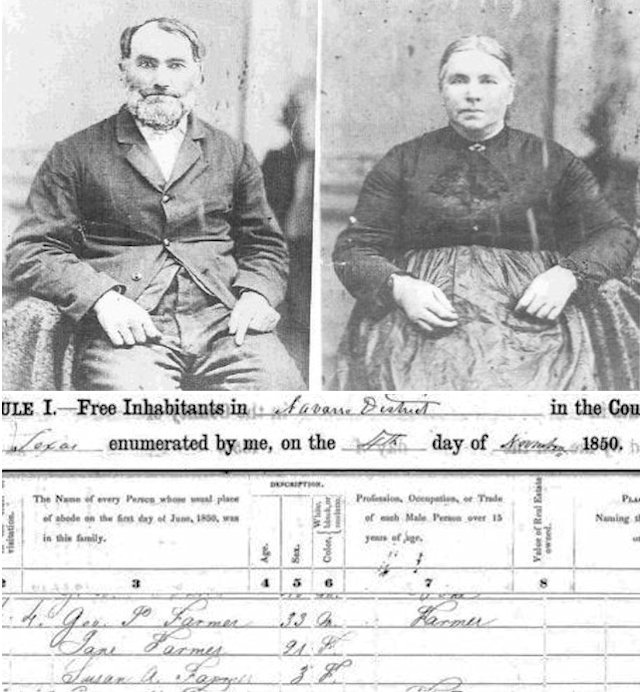

George Preston Farmer and wife Jane (daughter of pioneer Sam Woody) had been squatters on or near the site chosen for the fort in 1849. “Uncle Press” became the fort’s first sutler (civilian provisioner). (Photos from Tarrant County College NE.)

George Preston Farmer and wife Jane (daughter of pioneer Sam Woody) had been squatters on or near the site chosen for the fort in 1849. “Uncle Press” became the fort’s first sutler (civilian provisioner). (Photos from Tarrant County College NE.)

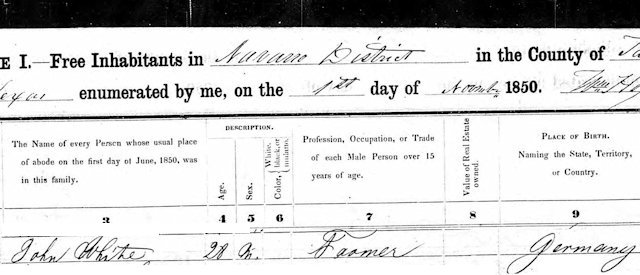

John White was listed as a farmer, but he also drove a freight wagon between Tarrant County and Houston and Galveston to fetch supplies for the fort and for local merchants such as Daggett and Leonard.

John White was listed as a farmer, but he also drove a freight wagon between Tarrant County and Houston and Galveston to fetch supplies for the fort and for local merchants such as Daggett and Leonard.

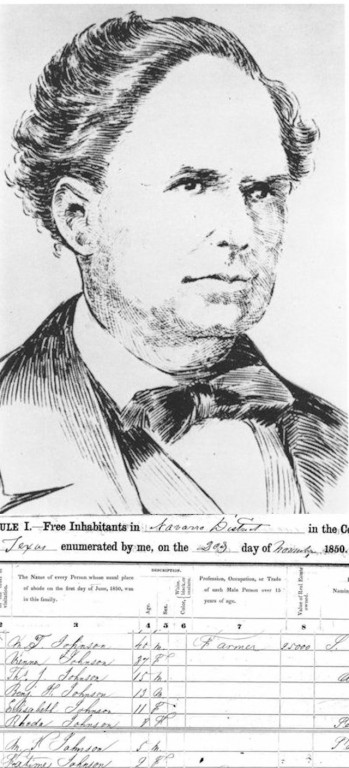

Middleton Tate Johnson was listed as a mere “farmer,” but by 1850 he was already the county’s wealthiest person, listing the value of his real estate at $25,000 ($680,000 today). He owned a lot of real estate in addition to his plantation at Johnson Station. Johnson had been instrumental in organization of the new county. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

Middleton Tate Johnson was listed as a mere “farmer,” but by 1850 he was already the county’s wealthiest person, listing the value of his real estate at $25,000 ($680,000 today). He owned a lot of real estate in addition to his plantation at Johnson Station. Johnson had been instrumental in organization of the new county. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

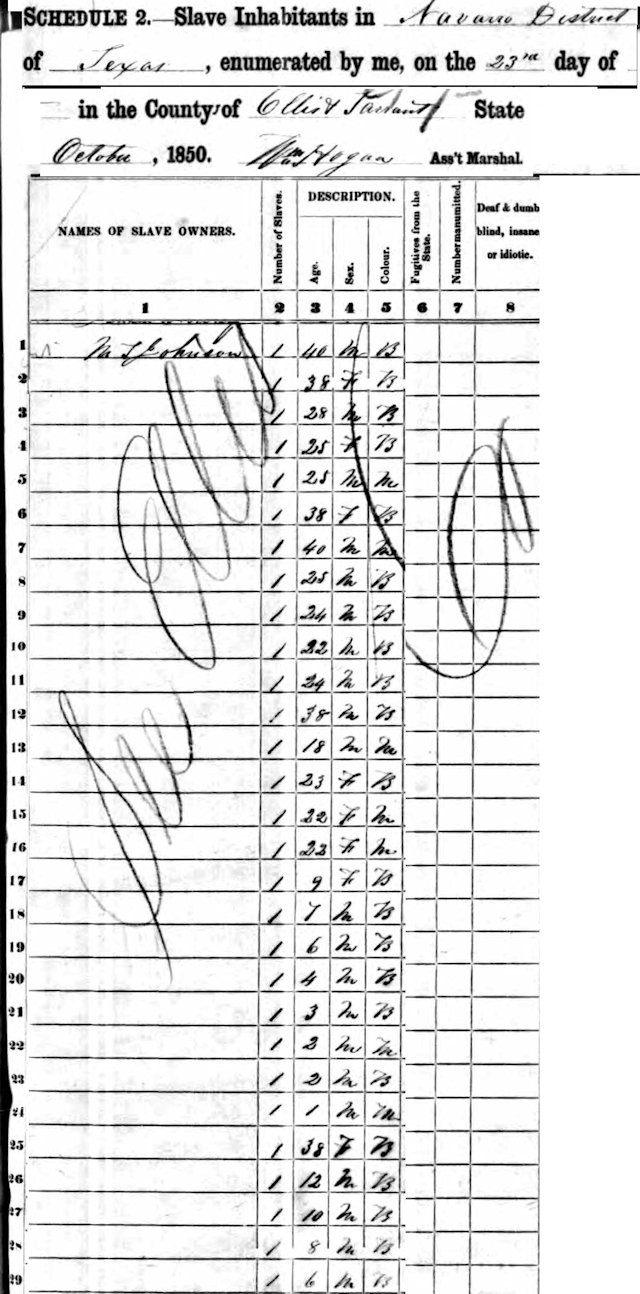

In October census-taker Hogan also enumerated slaves in Tarrant and Ellis counties. Middleton Tate Johnson was easily the largest slave-owner with twenty-nine persons (both “black” and “mulatto”), ranging in age from one to forty.

In October census-taker Hogan also enumerated slaves in Tarrant and Ellis counties. Middleton Tate Johnson was easily the largest slave-owner with twenty-nine persons (both “black” and “mulatto”), ranging in age from one to forty.

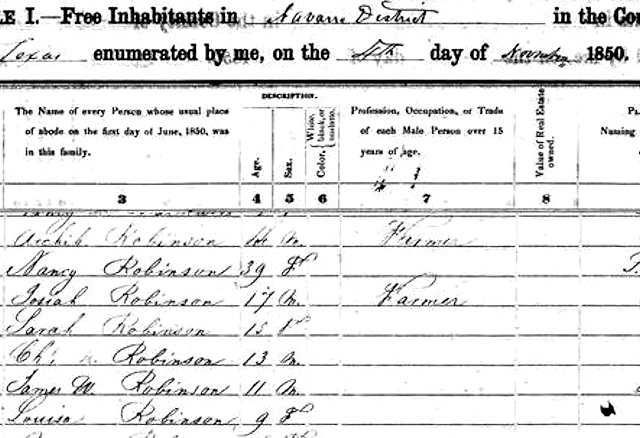

Some historians say farmer Archibald Robinson and Middleton Tate Johnson claimed ownership of the land that the fort was built on. Other historians say the site was Peters Colony land.

Some historians say farmer Archibald Robinson and Middleton Tate Johnson claimed ownership of the land that the fort was built on. Other historians say the site was Peters Colony land.

Matthew Jackson “Jack” Brinson (1826-1901) was the son-in-law of Middleton Tate Johnson and probably lived adjacent at Johnson Station. Historian Garrett writes that Brinson and Bob Slaughter built Fort Worth’s first brick store building in 1856. In 1857, during the Fort Worth-Birdville rivalry for county seat, Fort Worth supporter Brinson exchanged gunfire with Birdville supporter Samuel Tucker. Tucker was killed. Brinson was acquitted. (Photo from the December 15, 1912 Star-Telegram.)

Matthew Jackson “Jack” Brinson (1826-1901) was the son-in-law of Middleton Tate Johnson and probably lived adjacent at Johnson Station. Historian Garrett writes that Brinson and Bob Slaughter built Fort Worth’s first brick store building in 1856. In 1857, during the Fort Worth-Birdville rivalry for county seat, Fort Worth supporter Brinson exchanged gunfire with Birdville supporter Samuel Tucker. Tucker was killed. Brinson was acquitted. (Photo from the December 15, 1912 Star-Telegram.)

Historian Dr. Richard Selcer in The Fort That Became a City writes that one of the fort soldiers once stole a pig from the farm of William Little, who lived north of the river. When Major Arnold found out about the theft, he ordered the remains of the slaughtered pig to be hung around the soldier’s neck. The soldier was then tied to a post in the July sun.

Historian Dr. Richard Selcer in The Fort That Became a City writes that one of the fort soldiers once stole a pig from the farm of William Little, who lived north of the river. When Major Arnold found out about the theft, he ordered the remains of the slaughtered pig to be hung around the soldier’s neck. The soldier was then tied to a post in the July sun.

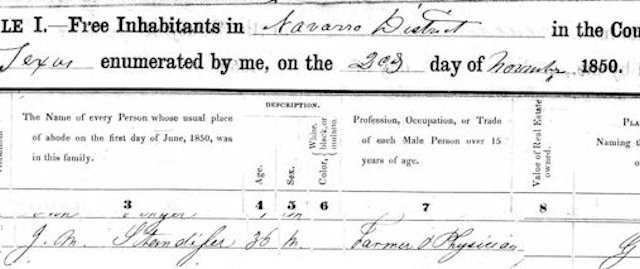

J. M. Standifer, “farmer & physician,” had served the fort as a civilian doctor until he was relieved by Army physician T. H. Williams.

J. M. Standifer, “farmer & physician,” had served the fort as a civilian doctor until he was relieved by Army physician T. H. Williams.

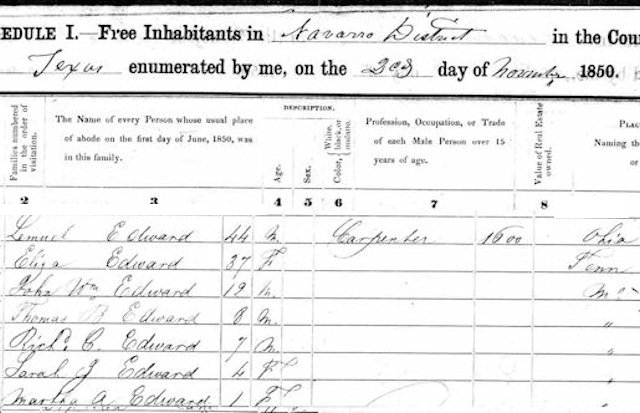

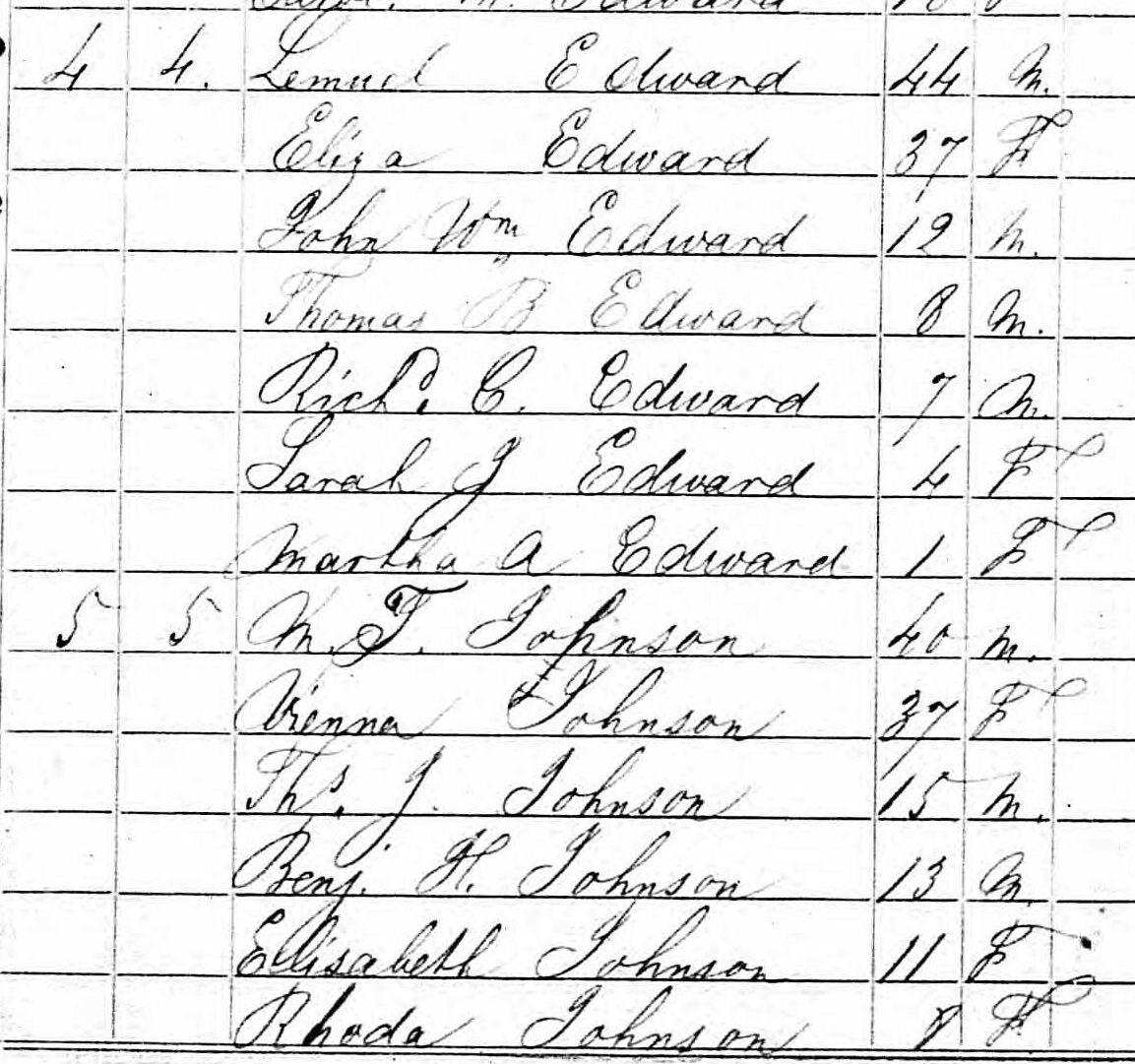

Census forms inevitably contain errors. “Lemuel Edward” was Lemuel James Edwards (1805-1869), father of Cass Edwards, who was born in 1851. Lemuel and family settled on the Clear Fork in today’s southwest Fort Worth in 1848. Lemuel Edwards was murdered by his son-in-law.

Census forms inevitably contain errors. “Lemuel Edward” was Lemuel James Edwards (1805-1869), father of Cass Edwards, who was born in 1851. Lemuel and family settled on the Clear Fork in today’s southwest Fort Worth in 1848. Lemuel Edwards was murdered by his son-in-law.

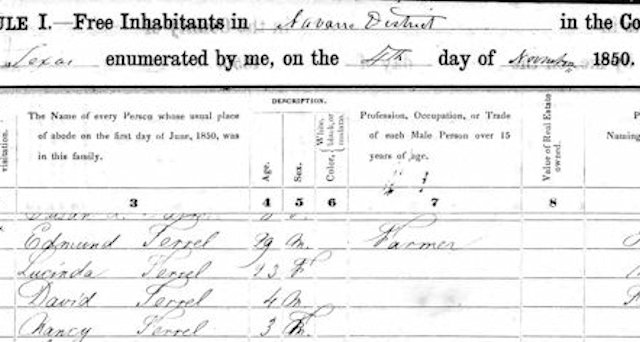

Edmund S. Terrell is said to have been the first white settler in this area, having come here as a trapper during the days of the republic in 1843. In 1844 Terrell and fellow trapper John P. Lusk were captured by Native Americans. Historian Selcer in The Fort That Became a City writes that Terrell operated a trading post at Live Oak Point (near Traders Oak) and that it was turned into a general store in 1849 by Henry Clay Daggett.

Edmund S. Terrell is said to have been the first white settler in this area, having come here as a trapper during the days of the republic in 1843. In 1844 Terrell and fellow trapper John P. Lusk were captured by Native Americans. Historian Selcer in The Fort That Became a City writes that Terrell operated a trading post at Live Oak Point (near Traders Oak) and that it was turned into a general store in 1849 by Henry Clay Daggett.

After the Army abandoned Fort Worth, Terrell operated the area’s first bar, the First and Last Chance Saloon, in one of the fort buildings. Terrell was elected Fort Worth’s first city marshal in 1873 as the city incorporated.

Perhaps the first church in the new county was Lonesome Dove Baptist Church, established at today’s Southlake in 1846. Among early members were preacher John Allen Freeman and wife Nancy, Henry Suggs and wife Saleta, Felix and Rachel Mulliken, James W. and Mary Anderson, Susanna Foster, James P. Halford, Lucinda Throop, and Mary Leonard (wife of Archibald Leonard). Lucinda was the widow of Charles Throop, in whose log cabin the church was founded. Charles had died just before the census was taken.

Perhaps the first church in the new county was Lonesome Dove Baptist Church, established at today’s Southlake in 1846. Among early members were preacher John Allen Freeman and wife Nancy, Henry Suggs and wife Saleta, Felix and Rachel Mulliken, James W. and Mary Anderson, Susanna Foster, James P. Halford, Lucinda Throop, and Mary Leonard (wife of Archibald Leonard). Lucinda was the widow of Charles Throop, in whose log cabin the church was founded. Charles had died just before the census was taken.

Freeman preached at the fort at least once, Selcer writes in The Fort That Became a City.

The juxtaposition of households in this census can create the misimpression that folks were neighbors. For example, Middleton Tate Johnson is listed right after Lemuel J. Edwards. But Johnson settled in today’s south Arlington, and Edwards settled in what is today southwest Fort Worth.

The juxtaposition of households in this census can create the misimpression that folks were neighbors. For example, Middleton Tate Johnson is listed right after Lemuel J. Edwards. But Johnson settled in today’s south Arlington, and Edwards settled in what is today southwest Fort Worth.

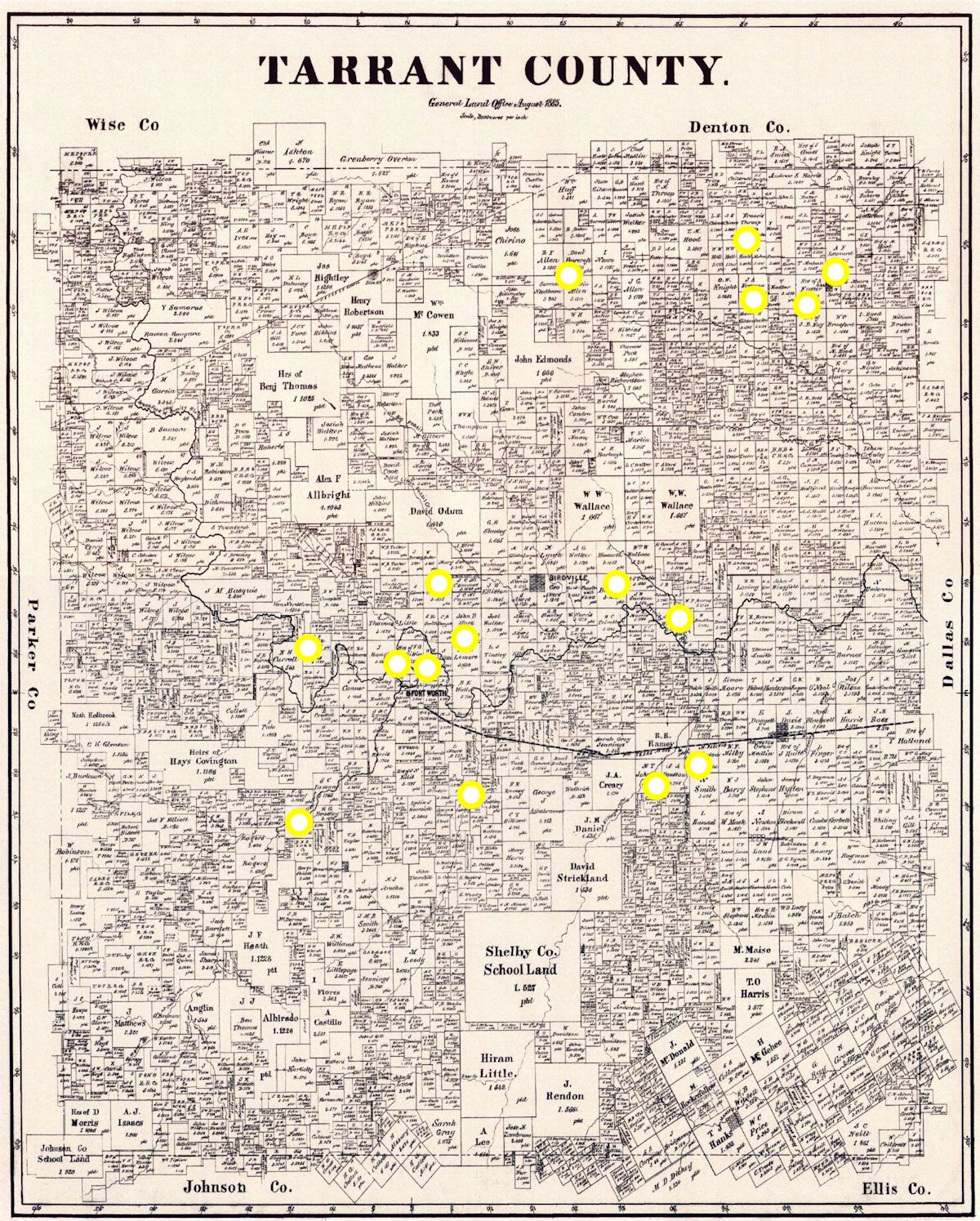

During that week in 1850 census-taker William Hogan and his horse covered many a mile over mostly open prairie. On this 1885 county map I have located the homesteads of just a few of the settlers mentioned here, from Lemuel J. Edwards in the southwest on the Clear Fork to preacher John Allen Freeman in the northeast near Grapevine. (1885 county map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

During that week in 1850 census-taker William Hogan and his horse covered many a mile over mostly open prairie. On this 1885 county map I have located the homesteads of just a few of the settlers mentioned here, from Lemuel J. Edwards in the southwest on the Clear Fork to preacher John Allen Freeman in the northeast near Grapevine. (1885 county map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Oh, don’t you wish that census-taker William Hogan had kept a diary and had made sketches of the people and places he saw as he counted noses 172 years ago?

By 1860, when the next federal census was taken, the fort indeed had become a city. Well, a town anyway. By 1860 the swords of Major Ripley Arnold and his men would be seven years gone. Only the plowshares of the farmers would remain. The number of “free inhabitants” of Tarrant County would increase almost tenfold to 5,170. The town of Fort Worth that had sprung from the Army’s Fort Worth would have a population of about 450.

A century after that first census, in 1950 census-takers in Fort Worth would count 356,268 noses, including three at 3404 North Pecan Street.

Today Fort Worth has more than 900,000 noses.

Thanks again for these posts, which always make for interesting reading. My great-great-grandfather moved his family here from central Tennessee in 1856, settling northwest of Fort Worth in the area where Tarrant, Wise, and Denton counties come together.

Thanks, John. Your great-great-grandfather saw a Texas we can scarcely imagine today.

I really appreciate being able to read this post and also your articles in the Star Telegram. All is so interesting. Wish I had discovered it sooner.

Thank you for your kind words, Ron.

We have corresponded before but, just wanted to remind you that I am the great great grand daughter of Col. Harris. I am currently on the Board for Pioneer Rest Cemetery. You may find it interesting that Col. Harris was among those who planted the flag on which the Fort was built. He was a skilled carpenter and crafted the rocking chair that is now on display in the County Court house museum. He later gave the chair to Colonel Peak’s then expecting wife. The chair remains in the Peak family (in Dallas) and is on loan to the museum. Thank you again for sharing this great historical background on Fort Worth.

Thanks, Sharon. From-the-git-goers like Harris and Ed Terrell saw a Texas and lived lives that we of later generations can’t imagine.

Thanks for posting this. I loved reading every word. I was born in Fort Worth in 1930. Though I have lived away for 51 years Fort Worth is the city I love. I have written a story of my years growing up in Fort Worth. It is titled “A Girls Fort Worth.” It has not been published. Wrote it for my children. Now my daughter and five grandchildren live in and near Fort Worth

Thank you, Betty. I have spent the last three years getting reacquainted with our hometown. I grew up not realizing how interesting Cowtown is.