As the Christmas season began in December 1921, the yuletide lyrics “all is calm, all is bright” rang hollow along Exchange Avenue on the North Side. Union workers of the two packing plants had walked out on strike, idling 95 percent of the plants’ workforce. Picketers walked their lines outside the two plants. Swift and Armour countered by hiring nonunion workers to keep the packing plants operating.

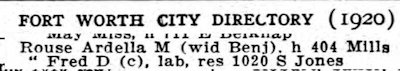

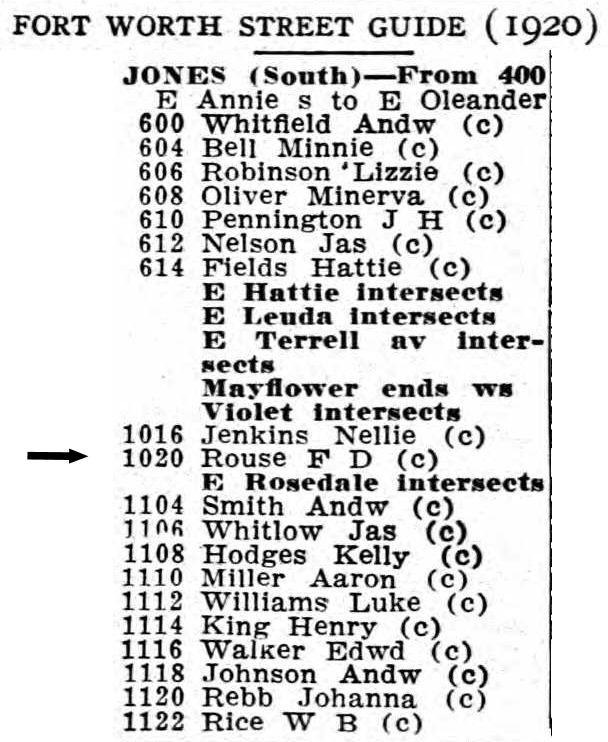

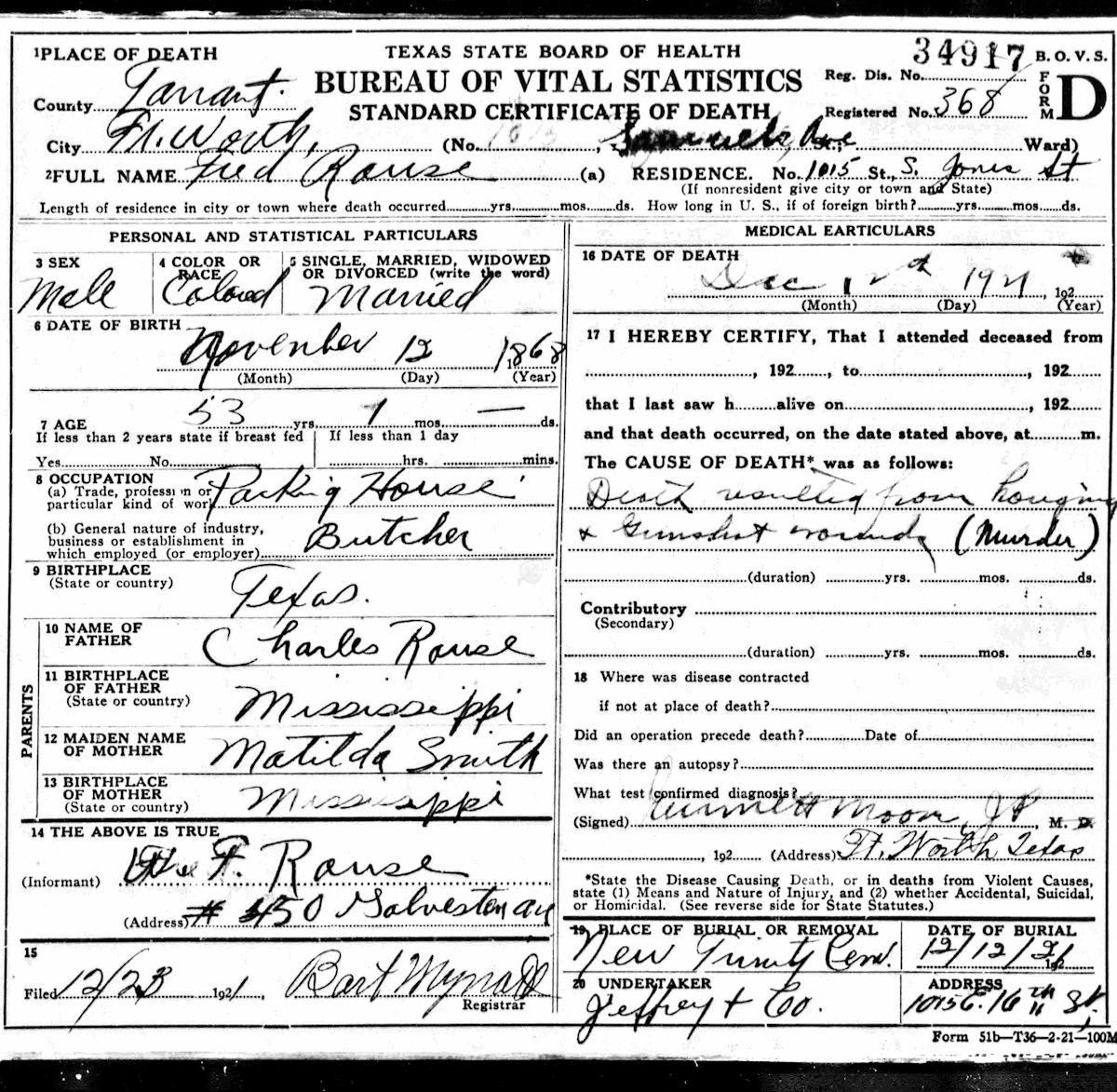

One of those nonunion workers was Fred D. Rouse, listed in the 1920 city directory as “(c), lab”: an African-American laborer. City directories identified African Americans with a “(c)” for “colored” until 1924. Rouse lived southeast of downtown in the African-American downtown of the early twentieth century. Rouse was born in Texas in 1868, but his parents, born in Mississippi, quite possibly had been slaves.

One of those nonunion workers was Fred D. Rouse, listed in the 1920 city directory as “(c), lab”: an African-American laborer. City directories identified African Americans with a “(c)” for “colored” until 1924. Rouse lived southeast of downtown in the African-American downtown of the early twentieth century. Rouse was born in Texas in 1868, but his parents, born in Mississippi, quite possibly had been slaves.

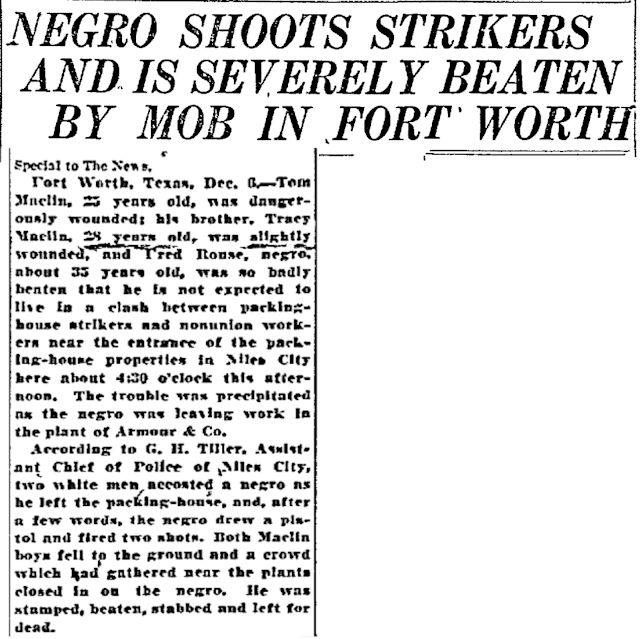

About 4:30 p.m. on December 6 as Fred Rouse left work (for the record: Rouse was fifty-three, not thirty-five, and worked at Swift, not Armour), he had to walk the gauntlet of picketers along Exchange Avenue. The Star-Telegram on December 7 described what happened next as “rioting” between union and nonunion partisans as Rouse was “roughly manhandled by a throng” of picketers. The Dallas Morning News said two picketing butchers—brothers Tom and Tracey Maclin—“accosted” Rouse. Rouse drew a pistol and shot the brothers. Tom was seriously wounded; Tracey was slightly wounded. The two brothers were hospitalized. Rouse was arrested by Niles City police officers, but angry strikers “wrested” Rouse from police custody and beat him “into insensibility,” the Star-Telegram wrote. “Stamped, beaten, stabbed, and left for dead,” the Dallas Morning News wrote. The angry strikers threw Rouse’s body into a wagon. The Dallas Morning News reported that Niles City Deputy Police Chief G. H. Tiller said he had thought Rouse was dead. A justice of the peace was called to hold an inquest. As an ambulance was transporting Rouse to a mortuary, attendants were startled when Rouse suddenly “rose up.” He was taken into a nearby drugstore for first aid and then rushed to City-County Hospital. (Niles City was the tiny incorporated enclave that encompassed the stockyards and packing plants.)

About 4:30 p.m. on December 6 as Fred Rouse left work (for the record: Rouse was fifty-three, not thirty-five, and worked at Swift, not Armour), he had to walk the gauntlet of picketers along Exchange Avenue. The Star-Telegram on December 7 described what happened next as “rioting” between union and nonunion partisans as Rouse was “roughly manhandled by a throng” of picketers. The Dallas Morning News said two picketing butchers—brothers Tom and Tracey Maclin—“accosted” Rouse. Rouse drew a pistol and shot the brothers. Tom was seriously wounded; Tracey was slightly wounded. The two brothers were hospitalized. Rouse was arrested by Niles City police officers, but angry strikers “wrested” Rouse from police custody and beat him “into insensibility,” the Star-Telegram wrote. “Stamped, beaten, stabbed, and left for dead,” the Dallas Morning News wrote. The angry strikers threw Rouse’s body into a wagon. The Dallas Morning News reported that Niles City Deputy Police Chief G. H. Tiller said he had thought Rouse was dead. A justice of the peace was called to hold an inquest. As an ambulance was transporting Rouse to a mortuary, attendants were startled when Rouse suddenly “rose up.” He was taken into a nearby drugstore for first aid and then rushed to City-County Hospital. (Niles City was the tiny incorporated enclave that encompassed the stockyards and packing plants.)

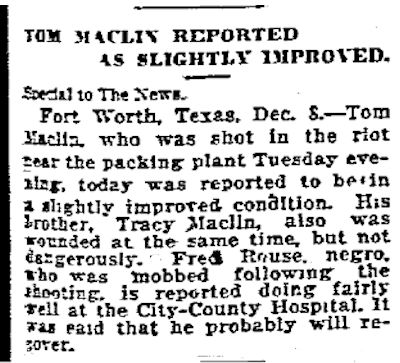

The days of December 7-10 were the calm between the storms. A court ordered an injunction to halt picketing at Armour. Picketing at Swift continued but was peaceful. Each side claimed to be winning the labor-management standoff. The Dallas Morning News in a brief on December 9 reported on the condition of the two Maclin brothers and Fred Rouse. The district attorney was delaying filing charges against Rouse pending Tom Maclin’s condition. If Tom Maclin died, Rouse would be charged with murder. If Tom Maclin recovered, Rouse would be charged with attempted murder.

The days of December 7-10 were the calm between the storms. A court ordered an injunction to halt picketing at Armour. Picketing at Swift continued but was peaceful. Each side claimed to be winning the labor-management standoff. The Dallas Morning News in a brief on December 9 reported on the condition of the two Maclin brothers and Fred Rouse. The district attorney was delaying filing charges against Rouse pending Tom Maclin’s condition. If Tom Maclin died, Rouse would be charged with murder. If Tom Maclin recovered, Rouse would be charged with attempted murder.

Events of the night of December 11 would make Tom Maclin’s condition a moot point.

That night about eleven o’clock, a mob of between twenty-five and thirty-three men entered City-County Hospital and announced that they had come for Fred Rouse. Night nurse Essie Slaton described the mob as young men dressed in ordinary clothing, although the Star-Telegram on December 12 said a few of the mob members wore handkerchiefs over their faces. The mob may have been a delegation of the Ku Klux Klan, which had a strong presence in Fort Worth and elsewhere in Texas in 1921. The nurses and doctors who saw the mob said they could not identify any of the men.

That night about eleven o’clock, a mob of between twenty-five and thirty-three men entered City-County Hospital and announced that they had come for Fred Rouse. Night nurse Essie Slaton described the mob as young men dressed in ordinary clothing, although the Star-Telegram on December 12 said a few of the mob members wore handkerchiefs over their faces. The mob may have been a delegation of the Ku Klux Klan, which had a strong presence in Fort Worth and elsewhere in Texas in 1921. The nurses and doctors who saw the mob said they could not identify any of the men.

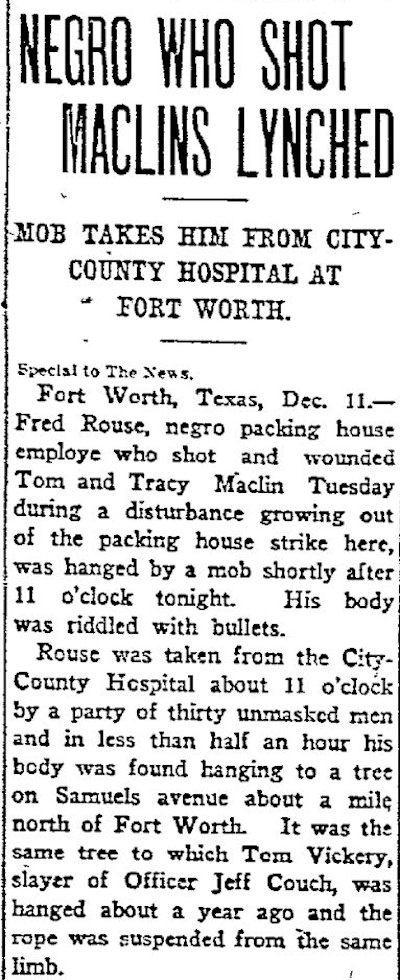

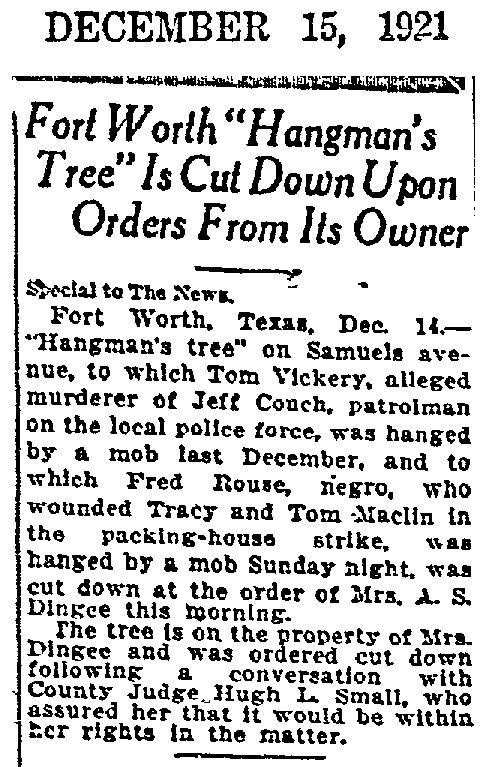

Just before midnight the body of Fred D. Rouse was found hanging by a rope from a hackberry tree on Samuels Avenue. He also had been shot eight times. Clip is from the December 12 Dallas Morning News. A year earlier the tree—which came to be known as “Hangman’s Tree”—had been used to hang Tom Vickery, a white man, who had been taken from jail by a mob after being arrested in the shooting death of police officer Jeff Couch. Vickery’s murder, too, may have been the work of the Klan.

Just before midnight the body of Fred D. Rouse was found hanging by a rope from a hackberry tree on Samuels Avenue. He also had been shot eight times. Clip is from the December 12 Dallas Morning News. A year earlier the tree—which came to be known as “Hangman’s Tree”—had been used to hang Tom Vickery, a white man, who had been taken from jail by a mob after being arrested in the shooting death of police officer Jeff Couch. Vickery’s murder, too, may have been the work of the Klan.

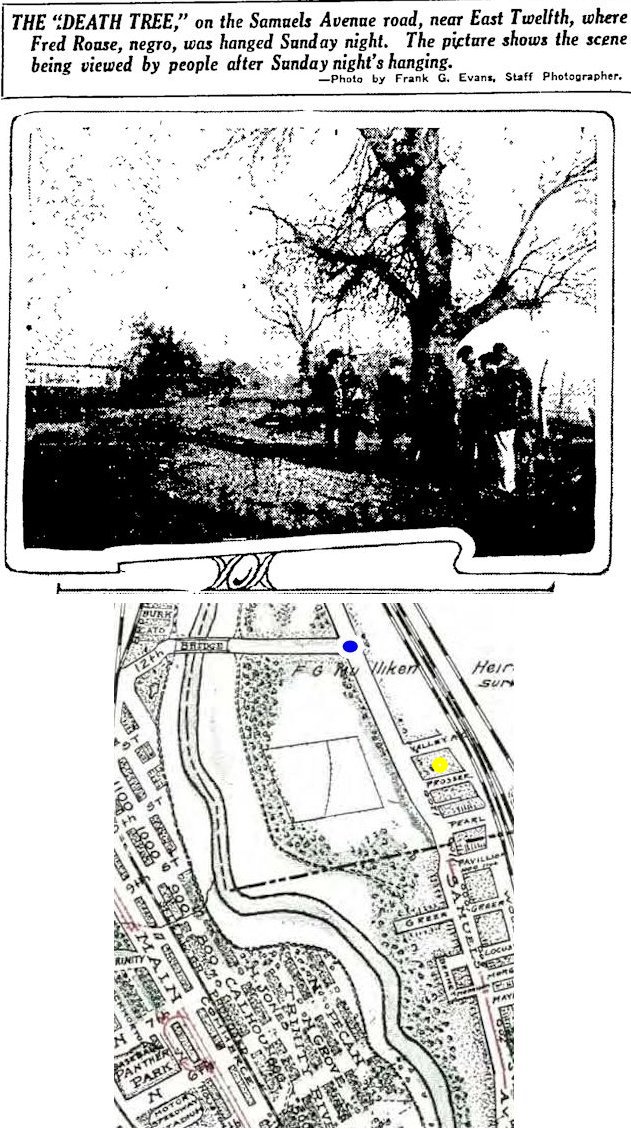

The Star-Telegram’s December 12 coverage included a photo of the “death tree” on Samuels Avenue at Northeast 12th Street. A 1919 map locates the tree (blue circle) northwest of Traders Oak (yellow circle). (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

The Star-Telegram’s December 12 coverage included a photo of the “death tree” on Samuels Avenue at Northeast 12th Street. A 1919 map locates the tree (blue circle) northwest of Traders Oak (yellow circle). (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

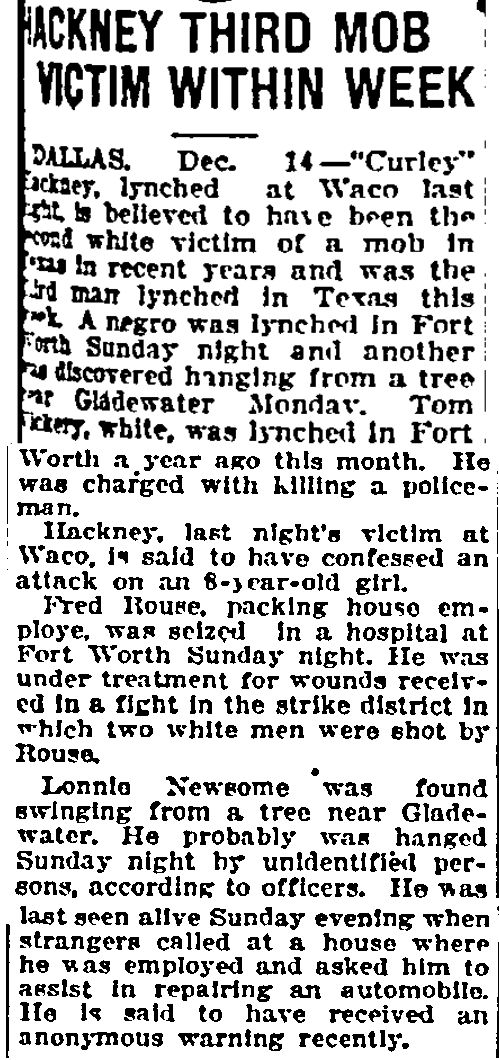

Also on December 14 the Dallas Morning News reported that Rouse was one of three men (two black, one white) lynched in Texas that week.

Also on December 14 the Dallas Morning News reported that Rouse was one of three men (two black, one white) lynched in Texas that week.

On December 14 the Star-Telegram reported that the grand jury had begun its investigation into the lynching of Fred Rouse.

On December 14 the Star-Telegram reported that the grand jury had begun its investigation into the lynching of Fred Rouse.

In February 1922 three men, including two men on the Niles City police force, were charged with murder. Policemen G. H. Tiller and W. H. Atherton and railroad switchman Tom Howell lived in the 100 block of Decatur Avenue about one mile north of Hangman’s Tree. Clip is from the February 13, 1922 Star-Telegram.

In February 1922 three men, including two men on the Niles City police force, were charged with murder. Policemen G. H. Tiller and W. H. Atherton and railroad switchman Tom Howell lived in the 100 block of Decatur Avenue about one mile north of Hangman’s Tree. Clip is from the February 13, 1922 Star-Telegram.

Two months later the three men were no-billed by a grand jury. By then G. H. Tiller had been elected police chief of Niles City. Clip is from the April 10, 1922 Star-Telegram.

Two months later the three men were no-billed by a grand jury. By then G. H. Tiller had been elected police chief of Niles City. Clip is from the April 10, 1922 Star-Telegram.

(Notice that in headlines the Star-Telegram identified African Americans—but not whites—by race.)

In October 1922 the original three men indicted were again indicted along with three more men, one of them probably a brother of the two wounded Maclin brothers. The six men proclaimed their innocence and were released on bond. Niles City Police Chief G. H. Tiller said he had been at home asleep when Rouse was hanged. Clip is from the October 2 Star-Telegram. As far as I can determine, the six suspects were never tried, and historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster say the same in Written in Blood (volume 2). In 1923 G. H. Tiller was still Niles City chief of police (Fort Worth would annex Niles City on August 1, 1923). Tom Howell was still a Rock Island switchman. The two Maclin brothers recovered from their wounds.

In October 1922 the original three men indicted were again indicted along with three more men, one of them probably a brother of the two wounded Maclin brothers. The six men proclaimed their innocence and were released on bond. Niles City Police Chief G. H. Tiller said he had been at home asleep when Rouse was hanged. Clip is from the October 2 Star-Telegram. As far as I can determine, the six suspects were never tried, and historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster say the same in Written in Blood (volume 2). In 1923 G. H. Tiller was still Niles City chief of police (Fort Worth would annex Niles City on August 1, 1923). Tom Howell was still a Rock Island switchman. The two Maclin brothers recovered from their wounds.

And the infamous Hangman’s Tree on Samuels Avenue? On December 15, 1921 the Dallas Morning News reported that the tree stood on the property of Mrs. A. S. Dingee, wife of the pioneer Fort Worth grocer. The property, which had belonged to Mrs. Dingee’s father, Colonel H. C. Holloway, was also the site of a cold spring. After lynchings on the Dingee property on December 22, 1920 and December 11, 1921, on December 14, eleven days before Christmas, Mrs. Dingee had Hangman’s Tree cut down, perhaps hoping to encourage good will toward men come Christmas 1922.

And the infamous Hangman’s Tree on Samuels Avenue? On December 15, 1921 the Dallas Morning News reported that the tree stood on the property of Mrs. A. S. Dingee, wife of the pioneer Fort Worth grocer. The property, which had belonged to Mrs. Dingee’s father, Colonel H. C. Holloway, was also the site of a cold spring. After lynchings on the Dingee property on December 22, 1920 and December 11, 1921, on December 14, eleven days before Christmas, Mrs. Dingee had Hangman’s Tree cut down, perhaps hoping to encourage good will toward men come Christmas 1922.

Fred D. Rouse is buried in New Trinity Cemetery in Haltom City.

Postscript: New York teacher and songwriter Abel Meeropol would not write “Strange Fruit” (as a poem) until 1937. Billie Holliday would record the poem set to music in 1939:

Trees don’t hang people…..

Pingback: Fort Worth asks, Can a klan hall become a place of healing? - Henry Gass

they cut down the skab hanging tree.