For a century a series of hotels stood on the downtown block bounded by 3rd and 4th streets and Main and Houston streets.

Today that block is Sundance Square Plaza.

Today that block is Sundance Square Plaza.

We can trace the history of Fort Worth’s “hotel block” back to August 1865. The Civil War had ended in April. Future civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt (1836-1930) visited Fort Worth from Marshall, Texas and found Fort Worth to present “a sad and gloomy picture.” Indeed Fort Worth was not much to look at just after the war: not many people living in a few modest wooden buildings on a few dirt streets. Nonetheless, Van Zandt, who would be president of Fort Worth National Bank for forty-six years, rented a house at 5th and Commerce streets and returned to Marshall to fetch his family. In early December 1865 the Van Zandts moved to Fort Worth by wagon. For $300 ($4,600 today) Van Zandt bought the entire city block bounded by 3rd and 4th streets and Main and Houston streets. He was gambling on a brighter future for his adopted “sad and gloomy” hometown. He moved his family into a house located in the northeast corner of the block. (Photo from Makers of Fort Worth.)

We can trace the history of Fort Worth’s “hotel block” back to August 1865. The Civil War had ended in April. Future civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt (1836-1930) visited Fort Worth from Marshall, Texas and found Fort Worth to present “a sad and gloomy picture.” Indeed Fort Worth was not much to look at just after the war: not many people living in a few modest wooden buildings on a few dirt streets. Nonetheless, Van Zandt, who would be president of Fort Worth National Bank for forty-six years, rented a house at 5th and Commerce streets and returned to Marshall to fetch his family. In early December 1865 the Van Zandts moved to Fort Worth by wagon. For $300 ($4,600 today) Van Zandt bought the entire city block bounded by 3rd and 4th streets and Main and Houston streets. He was gambling on a brighter future for his adopted “sad and gloomy” hometown. He moved his family into a house located in the northeast corner of the block. (Photo from Makers of Fort Worth.)

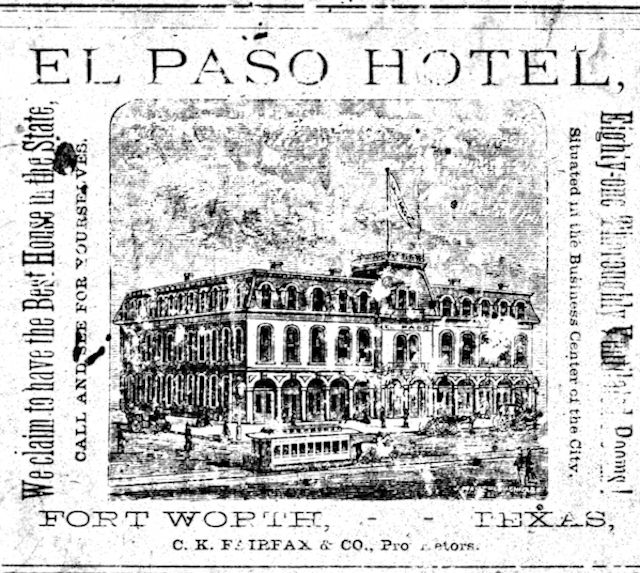

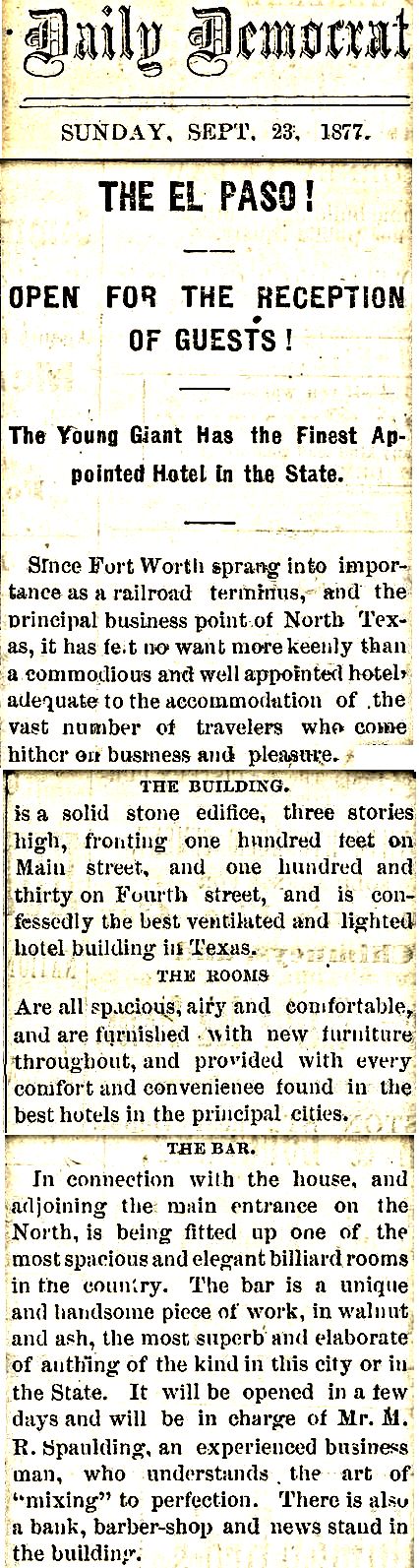

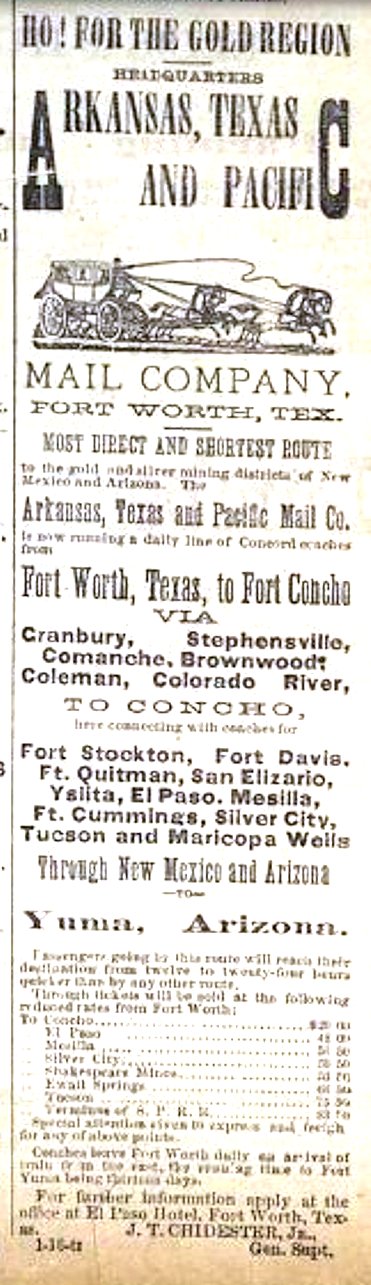

Fast-forward to 1877. Fort Worth’s future indeed improved after 1865. In 1877, one year after the railroad came to town, the eighty-one-room El Paso Hotel opened in the southeast corner of Van Zandt’s block under the proprietorship of Colonel Cyrus King Fairfax.

Fast-forward to 1877. Fort Worth’s future indeed improved after 1865. In 1877, one year after the railroad came to town, the eighty-one-room El Paso Hotel opened in the southeast corner of Van Zandt’s block under the proprietorship of Colonel Cyrus King Fairfax.

The El Paso was the city’s first three-story building. It was “substantially built of stone” and “thoroughly ventilated.” It featured gas lighting, walnut furniture, and a billiards room. Note the horse-drawn streetcar in the ad from the 1877 city directory.

The El Paso was the city’s first three-story building. It was “substantially built of stone” and “thoroughly ventilated.” It featured gas lighting, walnut furniture, and a billiards room. Note the horse-drawn streetcar in the ad from the 1877 city directory.

The opening of the El Paso received grudging mention in the Dallas Daily Herald of September 26.

The opening of the El Paso received grudging mention in the Dallas Daily Herald of September 26.

The stage coach also left from the hotel daily bound for Yuma, Arizona, twelve hundred miles away. The trip took thirteen days.

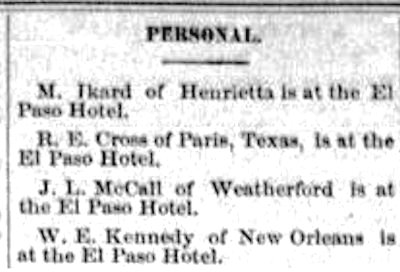

The El Paso was a favorite with out-of-towners. One of the El Paso’s early guests was said to have been outlaw Sam Bass. On December 21, 1877 Bass and associates checked in to enjoy the amenities after holding up a stage coach to Cleburne. Their take: $11. Clip is from the January 14, 1883 Gazette.

The El Paso was a favorite with out-of-towners. One of the El Paso’s early guests was said to have been outlaw Sam Bass. On December 21, 1877 Bass and associates checked in to enjoy the amenities after holding up a stage coach to Cleburne. Their take: $11. Clip is from the January 14, 1883 Gazette.

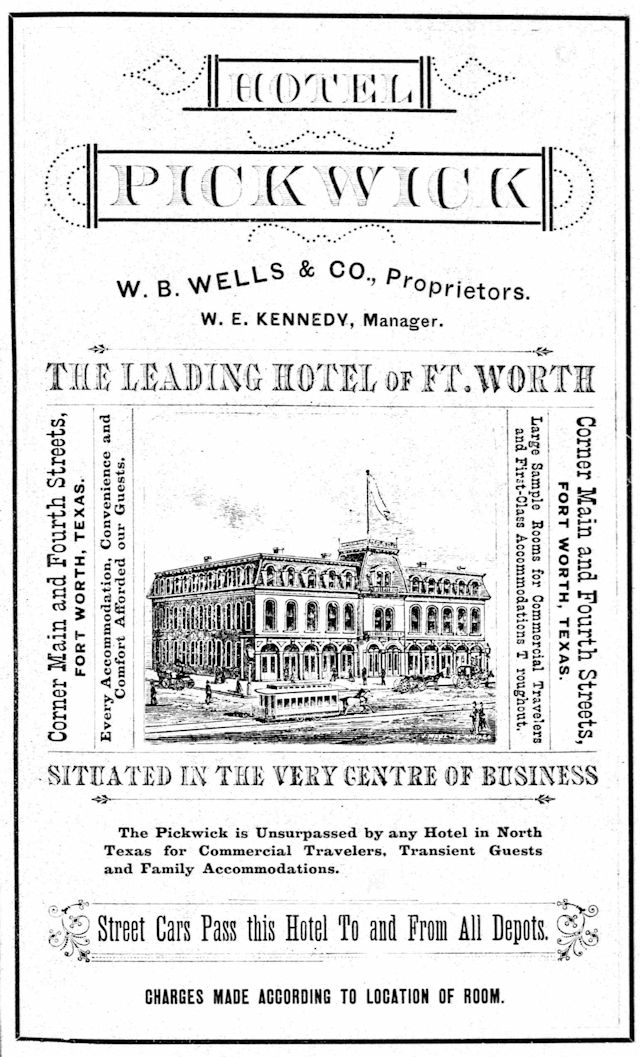

In 1884 the hotel changed its name to “Pickwick.” Ad is from the 1885 city directory.

In 1884 the hotel changed its name to “Pickwick.” Ad is from the 1885 city directory.

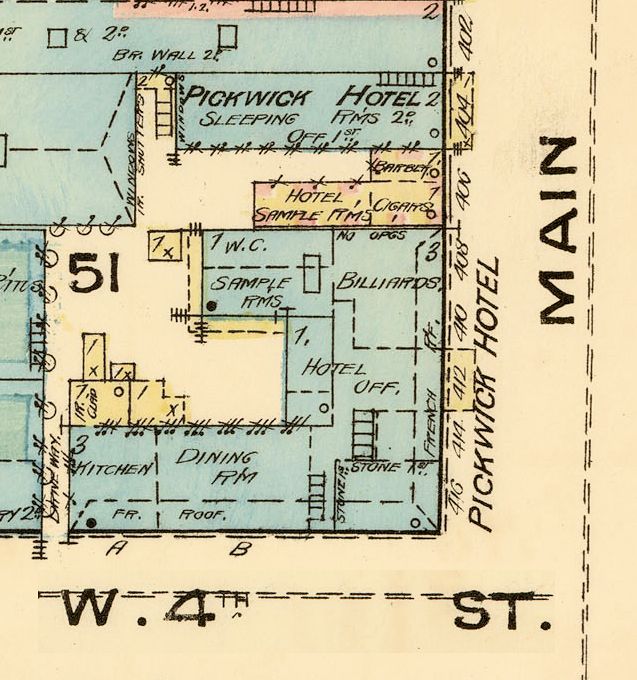

This Sanborn map also is from 1885.

On December 19, 1885 Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and his father-in-law, Chief Yellow Bear, came to Fort Worth. Yellow Bear was father of Wec-Keah, Quanah Parker’s first wife. Quanah Parker and Yellow Bear checked into the Pickwick Hotel and were assigned to an apartment in an adjacent building. That night Yellow Bear went to bed early, but Parker went out on the town with the foreman of the Dan Waggoner ranch. Two hours later Parker returned to the apartment and went to bed. (Photo from Tarrant County College Northeast, Heritage Room.)

On December 19, 1885 Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and his father-in-law, Chief Yellow Bear, came to Fort Worth. Yellow Bear was father of Wec-Keah, Quanah Parker’s first wife. Quanah Parker and Yellow Bear checked into the Pickwick Hotel and were assigned to an apartment in an adjacent building. That night Yellow Bear went to bed early, but Parker went out on the town with the foreman of the Dan Waggoner ranch. Two hours later Parker returned to the apartment and went to bed. (Photo from Tarrant County College Northeast, Heritage Room.)

The next morning the two men had not appeared for breakfast at the hotel. The Daily Gazette wrote: “The failure of the two Indians to appear at breakfast or dinner caused the hotel clerk to send a man around to awake them. He found the door locked and was unable to get a response from the inmates. The room was then forcibly entered, and as the door swung back the rush of the ‘deathly perfume’ through the aperture told the story. A ghastly spectacle met the eyes of the hotel employees.”

Yellow Bear was dead; Parker was near death at one point but recovered. Parker later told the Daily Gazette that he had returned to the apartment about midnight and found Yellow Bear in bed and the gas lamp extinguished. Parker said he lit the lamp, undressed, and turned out the lamp. But he apparently did not fully close the valve. He woke in the night and smelled gas but merely pulled a bedcover over his nose and went back to sleep. Clip is from the December 22, 1885 Daily Gazette.

Yellow Bear was dead; Parker was near death at one point but recovered. Parker later told the Daily Gazette that he had returned to the apartment about midnight and found Yellow Bear in bed and the gas lamp extinguished. Parker said he lit the lamp, undressed, and turned out the lamp. But he apparently did not fully close the valve. He woke in the night and smelled gas but merely pulled a bedcover over his nose and went back to sleep. Clip is from the December 22, 1885 Daily Gazette.

In 1892 a resident of the Pickwick was attorney Temple Houston, flamboyant son of Sam Houston. Clip is from the 1892 city directory.

In 1892 a resident of the Pickwick was attorney Temple Houston, flamboyant son of Sam Houston. Clip is from the 1892 city directory.

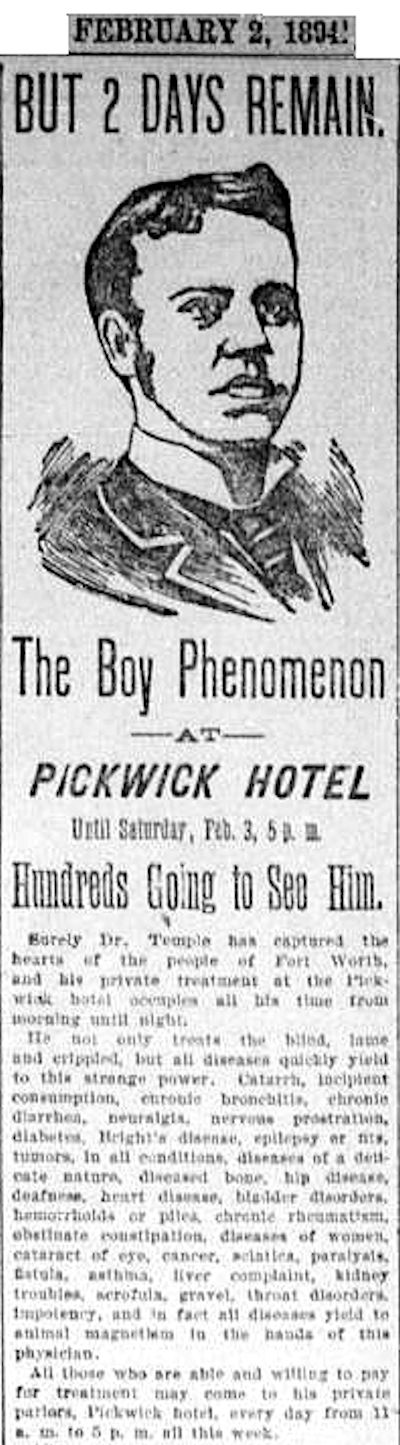

In 1894 Dr. Temple, the “boy phenomenon,” was at the Pickwick using his “strange power” to cure a list of ails that filled a long paragraph.

For the unfortunate folks whom Dr. Temple could not cure, in 1895 professors Myers and Sullivan of the Champion College of Embalming of Springfield, Ohio held a seminar for mortuary students in the hotel. Clip is from the January 21, 1897 Register.

Also in 1895 new management took over the Pickwick Hotel, changed its name to “Delaware,” and remodeled it. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Also in 1895 new management took over the Pickwick Hotel, changed its name to “Delaware,” and remodeled it. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

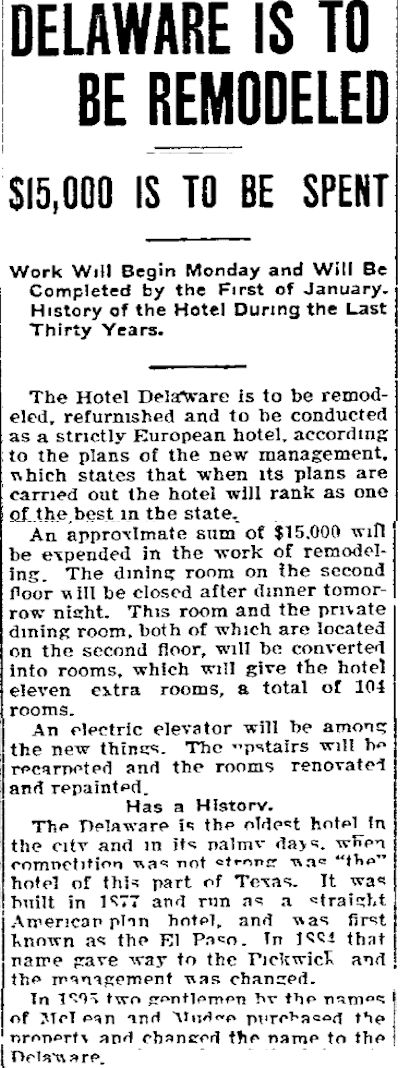

In 1902 the Delaware was remodeled again and got an electric elevator. Clip is from the November 30 Telegram.

In 1902 the Delaware was remodeled again and got an electric elevator. Clip is from the November 30 Telegram.

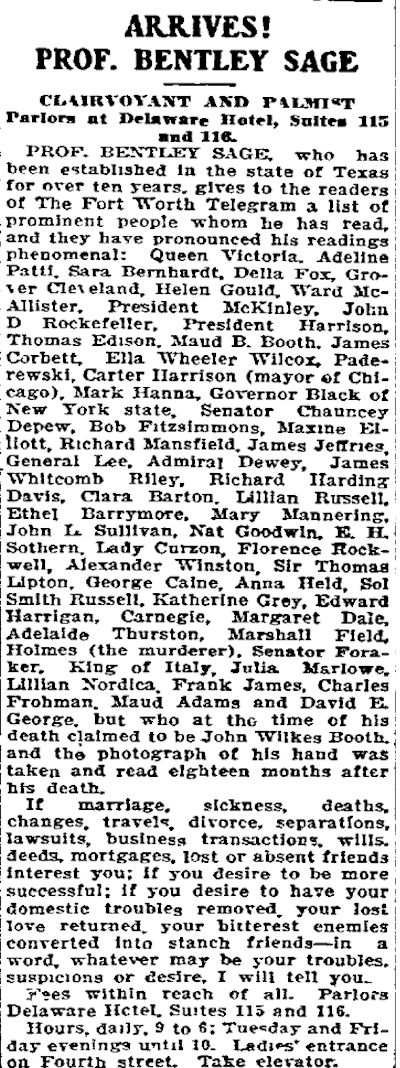

In 1905 “clairvoyant and palmist” professor Bentley Sage set up shop in suites 115 and 116. There the professor gave “readings” to residents who sought insights into “marriage, sickness, deaths, changes, travels, divorce, separations, lawsuits,” and so on. The professor listed “prominent people whom he has read,” including Queen Victoria, Grover Cleveland, President McKinley, John D. Rockefeller, Admiral Dewey, Ethel Barrymore, and “Holmes (the murderer).” “Fees within reach of all,” Sage’s ad read in the Telegram of April 5. “Ladies’ entrance on Fourth Street.”

In 1905 “clairvoyant and palmist” professor Bentley Sage set up shop in suites 115 and 116. There the professor gave “readings” to residents who sought insights into “marriage, sickness, deaths, changes, travels, divorce, separations, lawsuits,” and so on. The professor listed “prominent people whom he has read,” including Queen Victoria, Grover Cleveland, President McKinley, John D. Rockefeller, Admiral Dewey, Ethel Barrymore, and “Holmes (the murderer).” “Fees within reach of all,” Sage’s ad read in the Telegram of April 5. “Ladies’ entrance on Fourth Street.”

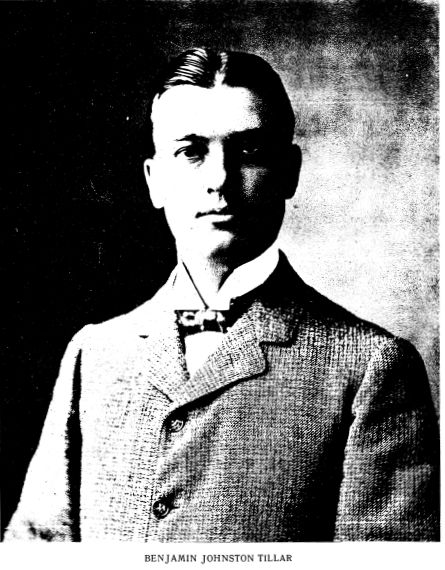

Perhaps the professor saw this coming: On April 1, 1908 the Telegram reported that Benjamin Tillar, who had bought up much of “hotel block,” including the Delaware Hotel, would build a huge new hotel on the site of the Delaware.

Perhaps the professor saw this coming: On April 1, 1908 the Telegram reported that Benjamin Tillar, who had bought up much of “hotel block,” including the Delaware Hotel, would build a huge new hotel on the site of the Delaware.

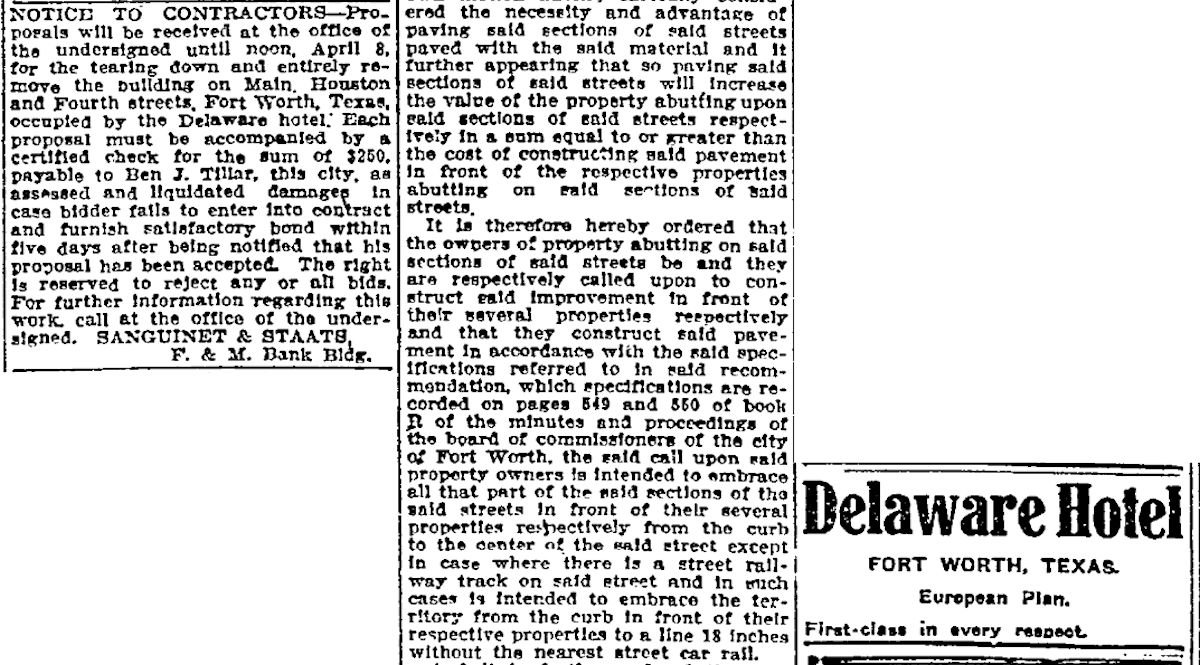

The venerable Delaware was living on borrowed time: In the April 4, 1909 Star-Telegram architects Sanguinet and Staats advertised for bids to tear down the hotel. Two columns over was an ad for the doomed hotel: “first-class in every respect.”

The venerable Delaware was living on borrowed time: In the April 4, 1909 Star-Telegram architects Sanguinet and Staats advertised for bids to tear down the hotel. Two columns over was an ad for the doomed hotel: “first-class in every respect.”

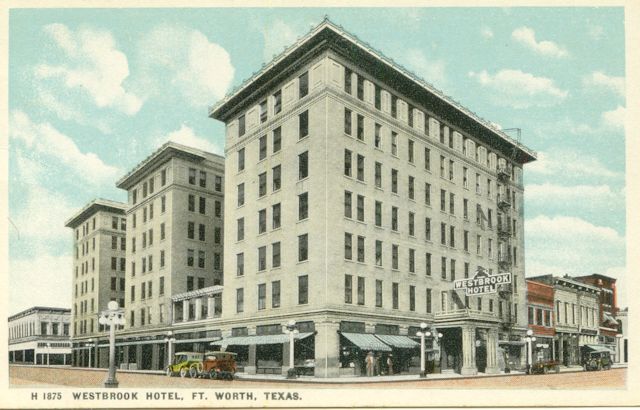

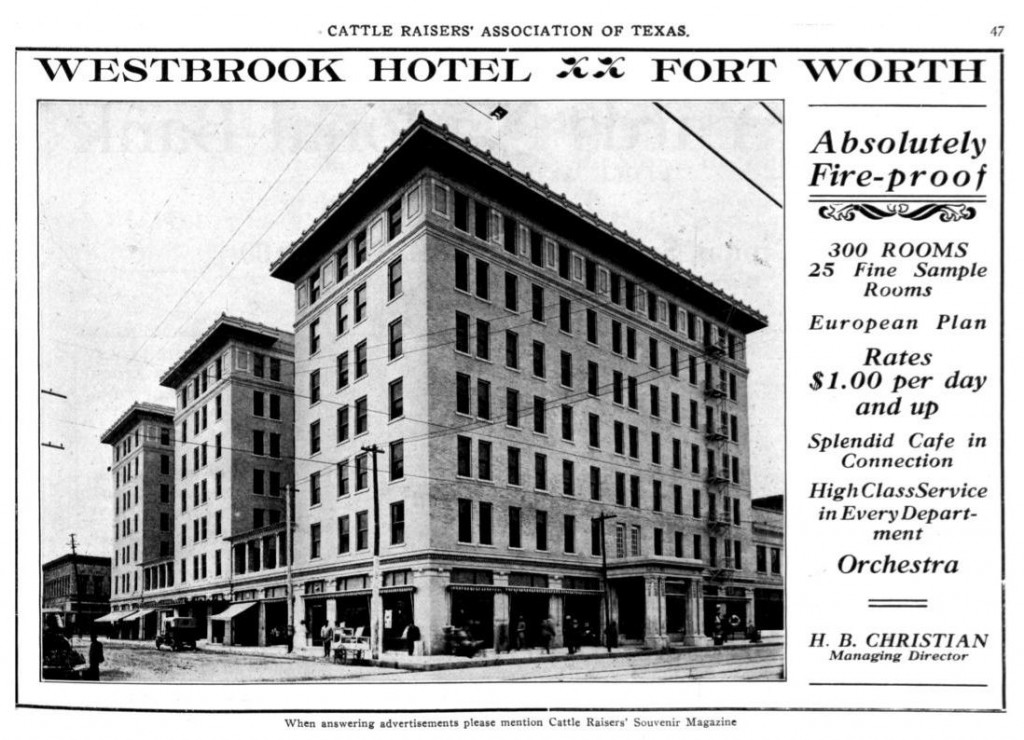

Tillar’s new hotel would be even grander than the Delaware, stretching the length of 4th Street between Main and Houston streets. Benjamin Tillar named his hotel “Westbrook” after his father, J. T. Westbrook Tillar.

Tillar’s new hotel would be even grander than the Delaware, stretching the length of 4th Street between Main and Houston streets. Benjamin Tillar named his hotel “Westbrook” after his father, J. T. Westbrook Tillar.

At the right edge of the postcard at Main and 3rd can be seen the little building at 400 Main Street (1902), Fort Worth headquarters of Northern Texas Traction Company. The building—with its Chisholm Trail mural—can be seen in the recent photo of Sundance Square Plaza at the top of the post.

The Westbrook opened on December 15, 1910. Clip is from the December 16 Star-Telegram.

Photo from University of North Texas Libraries.

Photo from University of North Texas Libraries.

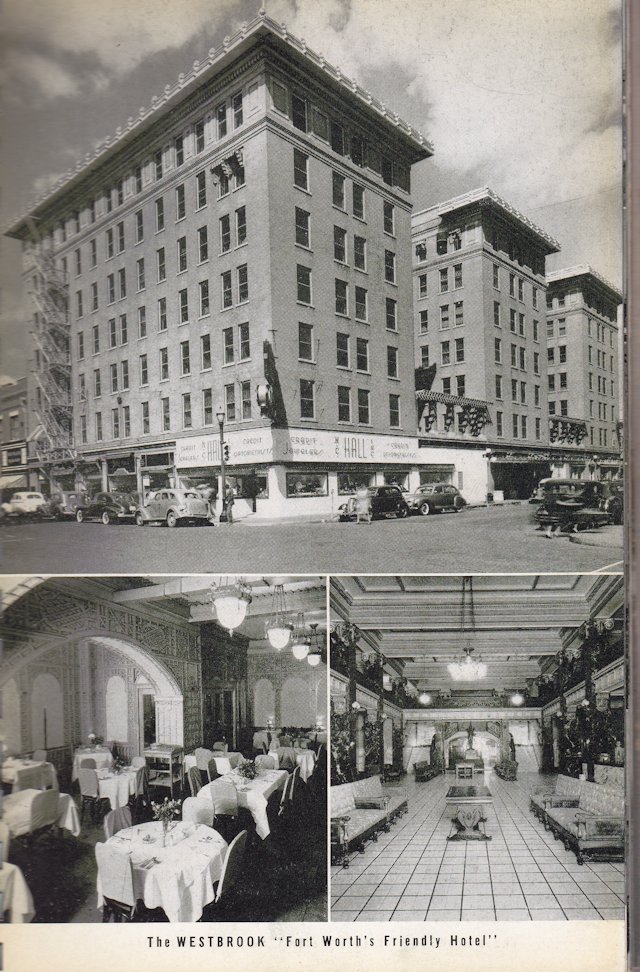

W. D. Smith photos from 1940.

W. D. Smith photos from 1940.

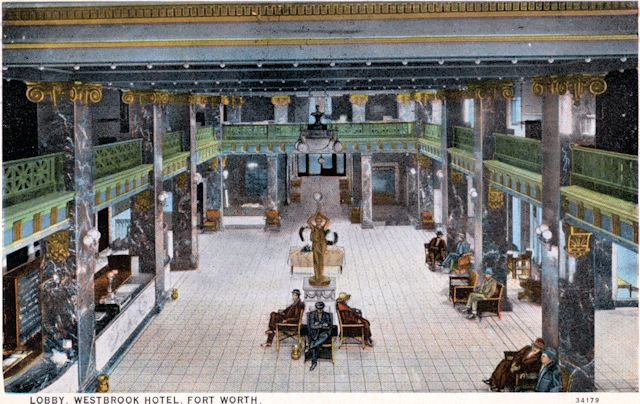

The new hotel, especially the lobby, was luxurious.

The new hotel, especially the lobby, was luxurious.

As a centerpiece in the lobby Benjamin Tillar placed the Golden Goddess, a large golden statue that he had brought from Italy in 1909. The Golden Goddess is a minimally dressed woman who holds a torch over her head. When the hotel opened she quickly reigned as queen of the lobby.

The Golden Goddess and her hotel became popular with wealthy cattlemen such as Burk Burnett. And during World War I the Goddess and the Westbrook became popular with British Royal Flying Corps cadets stationed at the three training fields around Fort Worth. The Goddess was especially popular with oilmen. Oilmen crowded the hotel lobby on October 17, 1917 after Texas & Pacific Coal Company, drilling on the McCleskey farm near Ranger, Texas, struck oil, sparking the Ranger oil boom. Superstitious oilmen at the Westbrook soon embraced the custom of rubbing the golden backside of the goddess for luck. Oilmen even wrote her an ode, “The Oilman’s Lament”:

Listen to me, you Golden Goddess

Standing high on your pedestal . . .

Let me rub your derriere for luck, for courage,

For bonanza . . .

And bequeath me your favors . . .

In black gold!

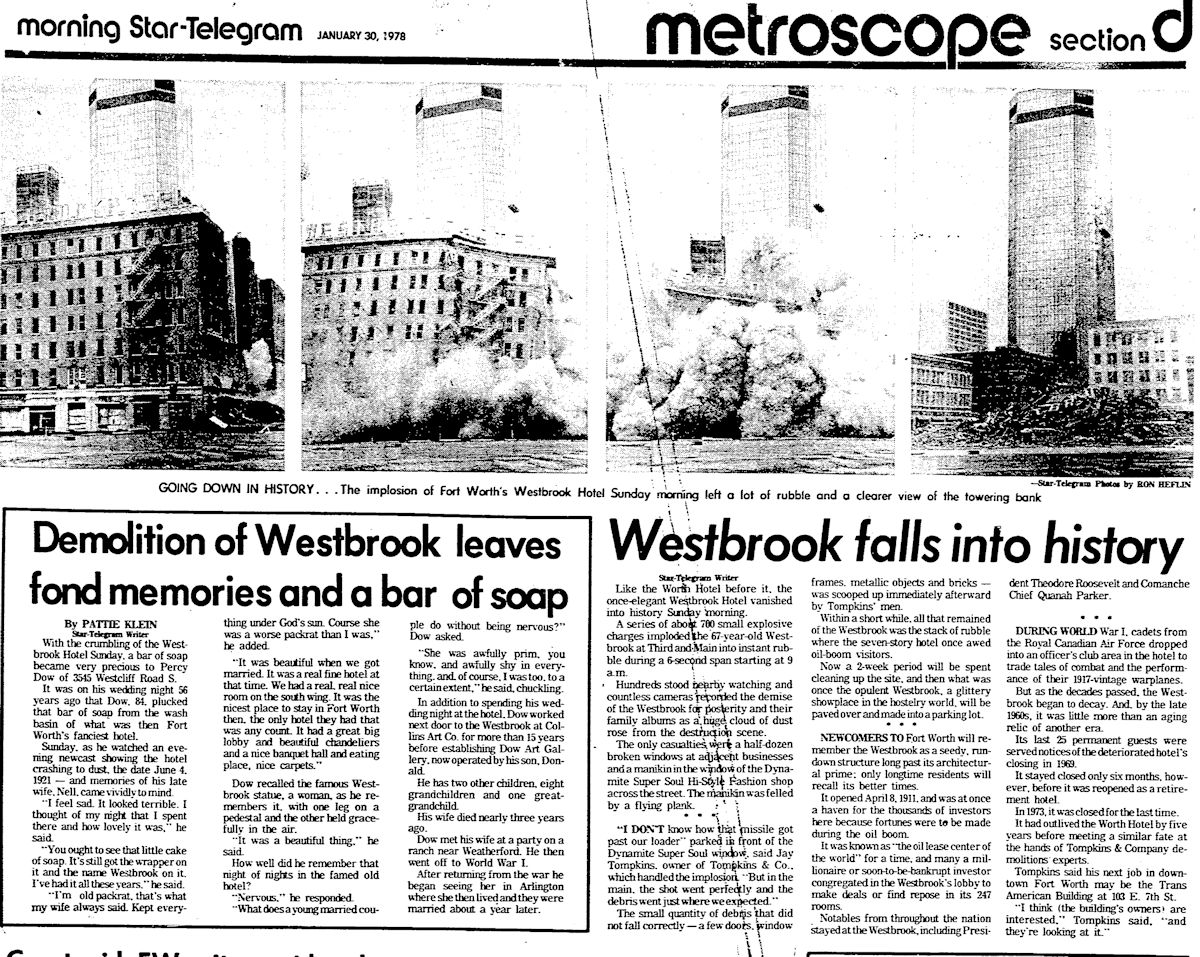

Many of those oilmen had better luck than the Westbrook Hotel had. The Westbrook was imploded in 1978, and most of “hotel block” served as a parking lot until 2012, when construction of the Westbrook retail building began as part of the Sundance Square Plaza development.

Many of those oilmen had better luck than the Westbrook Hotel had. The Westbrook was imploded in 1978, and most of “hotel block” served as a parking lot until 2012, when construction of the Westbrook retail building began as part of the Sundance Square Plaza development.

The Golden Goddess also had better luck. In 2003 Fort Worth’s Petroleum Club bought the Golden Goddess, had her restored (covered with 250 sheets of gold leaf), and put her on display in the club. A new generation of oilmen revived the good-luck custom.

The Golden Goddess also had better luck. In 2003 Fort Worth’s Petroleum Club bought the Golden Goddess, had her restored (covered with 250 sheets of gold leaf), and put her on display in the club. A new generation of oilmen revived the good-luck custom.

Sam Bass, Quanah Parker, Temple Houston, embalming classes, the Golden Goddess—“hotel block” had a full history, considering the humble purpose it served originally in 1865 after Major Van Zandt bought the property in his adopted “sad and gloomy” hometown. Years later, in his autobiography Force without Fanfare, Van Zandt recalled the first use he made of the future hotel site: “Down on the end of the block where the Westbrook Hotel now stands, I put my pigpen and cow lot.”

Other posts about Van Zandt:

Van Zandt: Father and Son, State and City (Part 1)

From Adams’s Beaver Hat to Dylan’s Coffee Table

Blue and Gray: “Best of Friends . . . As If We Had Fought Side by Side”

A Rock and a Lock: Old-Fashioned Customer Service at the Trinity River Bank

Buttons and Bones: The Life, Death, and 3 Burials of 2 Confederate Generals

I just came across your site while looking for information about the Westbrook Hotel. My Dad’s mother spent most of her life in a room there. When we visited, I was a little kid. I was amazed at the artwork and all the wonderful things in the lobby etc. I remembered my Grandmother’s bathroom was small green tiles. The staff knew me and always made sure I was safe when I checked out everything. Got candy from the cigarette stand and sodas from the restaurant. It was magical to me. Thanks for sharing.

I am a caregiver for a 90 y/o man, born in 1933. When he was only 10 years old his mother sent him to the hotel to work. He got a job doing everything from carrying bags to rooms to running odd errands. His nickname was Bobby Nickel because he would do anything for a nickel!

We are writing his life story and researching the hotel. I read him your comment and he said he knew everyone that stayed there. He has wonderful memories!

Thank you, sir, for the wonderful history of the Westbrook Hotel (in it’s last incarnation, at least).

My grandfather, Judge Tom Simmons, resided in the Westbrook Hotel for years (along with his daughter, Anne Frances Simmons [m. Stripling] for a time). My auntie always asked my grandmother if living at the Westbrook was akin to “Eloise” from the books set at the Plaza Hotel.

Just prior to the demolition, my mother obtained a beautiful (and heavy!) ceiling fan from the Hotel, which I still keep.

Again, very many thanks for your lovely research and dedication to Fort Worth history.

Thank you, Dana. What a great relic to have from a grand part of Fort Worth history.

Sir, I’m speechless. There’s an historian who’s name I can’t recall currently that wrote books about Shreveport and bossier city Louisiana. I adore those books. I adore this accounting, as well. I’ll look up more from you shortly.

I just wanted to thank you for your timestamping exploration. I learned more in 5 minutes than I’ve learned in the last 7 years I’ve been here.

Thank you, sir! I am learning right along with you.

Mike I really miss your Hometown posts, I enjoyed this one about the Hotels. I remember the Westbrook. Hope you are doing O.K.

Thanks, Lois. I have not missed a daily post to Hometown by Handlebar in at least two years. I post every day of the week and will continue to. I no longer tease the posts on Facebook because, after 840 posts, the blog just never developed a following on Facebook. Every post remains accessible on the blog. And the blog is searchable by keyword.

Mike, you really should give tours of DOWNTOWN Fort Worth.

I have learned a lot in the last almost four years. Before then I was not even sure which streets were Houston, Commerce, Throckmorton, Calhoun, etc.