Fort Worth had rudimentary telephone service by 1880—before it had a school system or a water system. Physician Julian T. Feild is said to have owned the first telephone in town. The city’s second phone line connected the Club Room Saloon with the office of the Fort Worth Democrat newspaper, one block away, because editor B. B. Paddock considered the saloon to be “the most prolific news source of the period.”

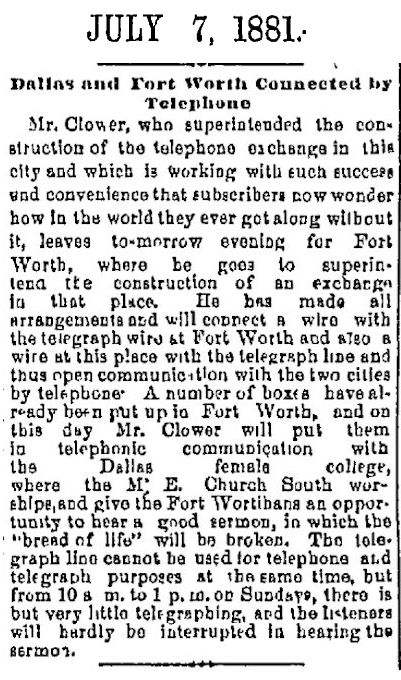

By 1881 Fort Worth was connected in a tenuous way even to Dallas. This clip from the July 7 Dallas Weekly Herald announced that Daniel M. Clower would travel from Dallas to Fort Worth to connect the two cities via the telegraph wire between them. Note that “A number of boxes have already been put up in Fort Worth.” Also note that Clower was going to connect Fort Worth to a Methodist Episcopal Church South Sunday service in Dallas so Fort Worthians could “hear a good sermon in which ‘the bread of life’ will be broken.” The single wire between Fort Worth telephones and the church service in Dallas could perform only one task at a time—either transmit telegraphs or transmit the church service by telephone. Seems that in the beginning, even God was on a party line.

By 1881 Fort Worth was connected in a tenuous way even to Dallas. This clip from the July 7 Dallas Weekly Herald announced that Daniel M. Clower would travel from Dallas to Fort Worth to connect the two cities via the telegraph wire between them. Note that “A number of boxes have already been put up in Fort Worth.” Also note that Clower was going to connect Fort Worth to a Methodist Episcopal Church South Sunday service in Dallas so Fort Worthians could “hear a good sermon in which ‘the bread of life’ will be broken.” The single wire between Fort Worth telephones and the church service in Dallas could perform only one task at a time—either transmit telegraphs or transmit the church service by telephone. Seems that in the beginning, even God was on a party line.

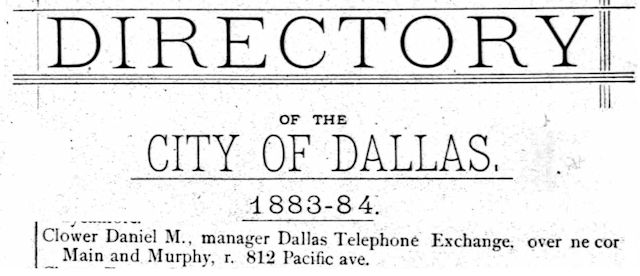

Clower was manager of the Dallas Telephone Exchange.

Clower was manager of the Dallas Telephone Exchange.

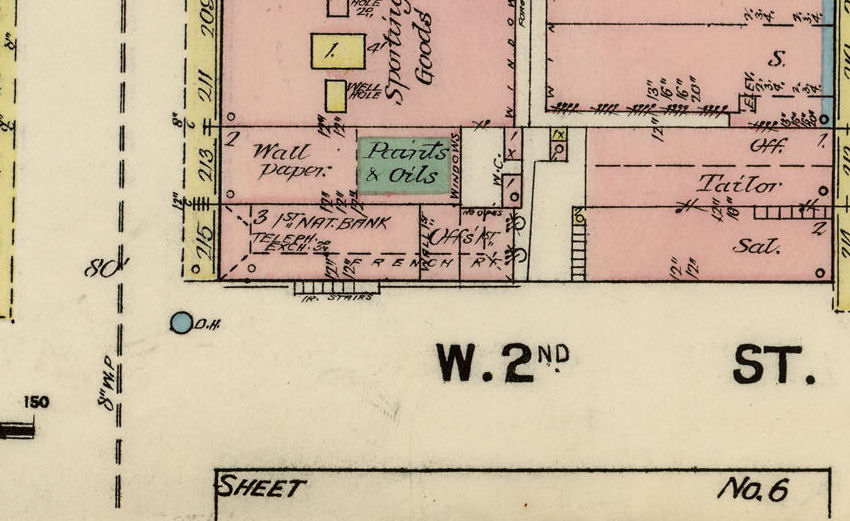

According to this plaque at the corner of West 2nd and Houston streets in downtown Fort Worth, Southwest Telegraph and Telephone Company started a telephone exchange at that corner on September 1, 1881 with about forty telephone subscribers. By 1883 Fort Worth had 168 subscribers.

Indeed, a map of 1889 shows a telephone exchange on the third floor of the First National Bank building at West 2nd and Houston streets. (In 1890 the mayor of Fort Worth would be scandalized by his relationship with a “telephone girl” at this exchange.)

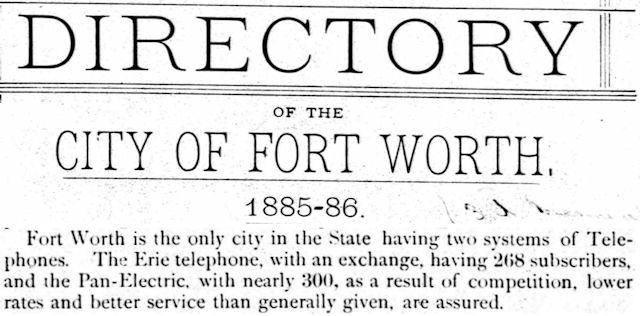

The 1885 city directory boasted that Fort Worth had two telephone systems and more than five hundred subscribers.

The 1885 city directory boasted that Fort Worth had two telephone systems and more than five hundred subscribers.

“I hear dead people”: By 1883 Fort Worth had gone telephone gaga. A connection was made even between “the city” and the new city cemetery (Oakwood) on the other side of the river. And what more appropriate medium to use for a phone connection in Cowtown than a barbed wire fence around a pasture? (Call it “Southwestern Cow Bell.”) John Peter Smith in 1879 had donated pasture land north of the river for the new cemetery. Clip is from the May 5, 1883 Gazette.

“I hear dead people”: By 1883 Fort Worth had gone telephone gaga. A connection was made even between “the city” and the new city cemetery (Oakwood) on the other side of the river. And what more appropriate medium to use for a phone connection in Cowtown than a barbed wire fence around a pasture? (Call it “Southwestern Cow Bell.”) John Peter Smith in 1879 had donated pasture land north of the river for the new cemetery. Clip is from the May 5, 1883 Gazette.

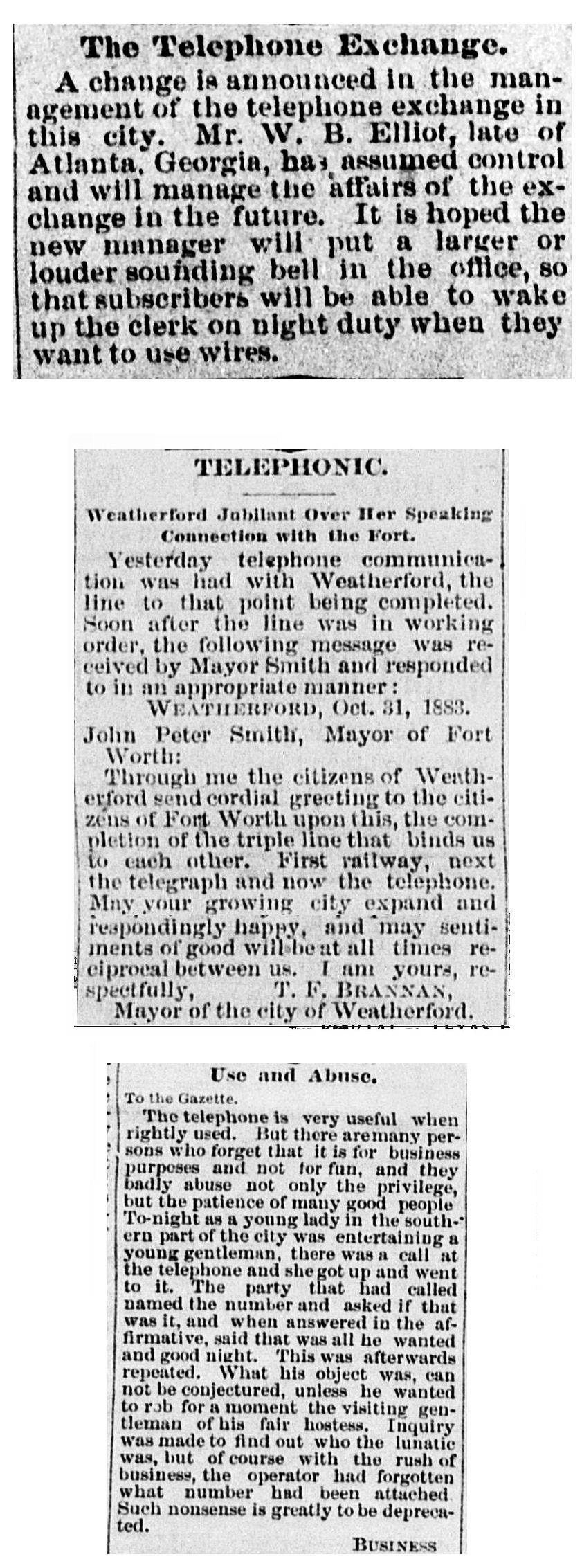

These Gazette clips of 1883 and 1884 show the evolution of the newfangled gizmo in Fort Worth. Making a phone call at night might require waking the clerk at the exchange. On Halloween 1883 the cities of Weatherford and Fort Worth were connected. The bottom clip, a letter to the editor about telephone etiquette, could have been written in modern times.

In fact, the modernity of that letter to the editor leads us to a jarring aspect of the development of the telephone. If you’re like me, you think of the telephone as a high-tech tool of the modern age, not as a form of instant personal communication available to people of the wild West. But in the 1880s that’s where Fort Worth and many other towns were: smack dab in the wild West. The frontier would not be declared closed until 1890. Fort Worth and the West in general were still pretty untamed places in the 1880s. A pistol was a common part of a man’s daily dress, same as a coat or pantaloons. Greenhorns were carried out of saloons feet first. Outlaws on horses held up banks and trains. Violence still flared between white settlers and Native Americans. Many of the best-known gunfights occurred after 1880.

Somehow the telephone just does not fit into that wild and woolly picture. Watch any western movie. Ain’t no telephones, pardner. Just an occasional telegraph. I don’t know about you, but there is no place in my image of the rootin’-tootin’ wild West for the Princess phone.

And yet the technology was there.

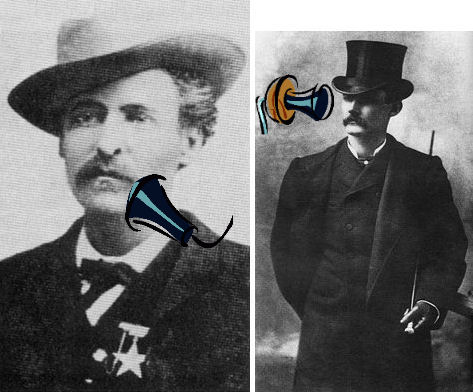

Think of it. This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that on February 8, 1887, instead of leaving us with a famous shootout to reenact annually, Jim Courtright and Luke Short (photos from Tarrant County College NE and Wikipedia) could have just talked out their differences over the telephone:

[Courtright uses a hand-cranked wall telephone to place his call through an operator and waits for an answer.]

[Ring, ring.]

Short (answering): “It’s your dime.”

Courtright: “Hello, Luke? This is Jim. I hear you ain’t gonna let my detective agency provide the White Elephant with special protection. Luke Short, you’re a low-down, side-windin’ weasel.”

Short: “Oh, yeah? Well, it takes one to know one. I ain’t payin’ you a cent of shakedown money, you lily-livered, yellow-bellied son of a sheep herder.”

Courtright: “I know you are, but what am I?”

Short: “You stink.”

Courtright: “Buzzard breath.”

Short: “You call yourself a fast draw? Hah! You’re so slow, molasses won’t run down your leg.”

Courtright: “You’re so crooked, you could swallow nails and spit out corkscrews.”

[Both men burst out laughing.]

Courtright: “There. Lordy, I feel much better now. Thanks for listening, Luke.”

Short: “Anytime, Jim. Still on for poker Friday?”

Courtright: “Can’t. Promised the wife I’d help hang some drapes.”

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that on October 5, 1892 the Dalton brothers (Bob, Emmett, and Grat) could have planned their simultaneous holdup of two banks at Coffeyville, Kansas by telephone:

[Ring, ring.]

Bob Dalton: “Hello? That you, Emmett? Dadgummit, bro, I’ve been trying to phone you for hours. Your line’s been busy. We gotta work out the details of who hits which bank tomorrow.”

Emmett Dalton: “Sorry, Bob. I know, I know. Darned teenager’s been yakkin’ on the phone all night.”

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that on October 26, 1881 in Tombstone, Arizona Territory outlaws Ike and Billy Clanton, Billy Claiborne, and Tom and Frank McLaury could have phoned lawmen Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday to schedule their big gunfight:

[Ring, ring.]

Billy Clanton: “Hello, Wyatt?”

Doc Holliday: “Wyatt ain’t here. This is Doc. Who’s calling?”

Billy Clanton: “Billy. Billy Clanton.”

Doc Holliday: “Oh. Billy. I reckon you’re calling about the gunfight tomorrow. Can I take a message?”

Billy Clanton: “Sure. Tell Wyatt we were thinking maybe sometime after lunch. Threeish? The streets are all booked, but we reserved the O.K. Corral. Got that?”

Doc Holliday (writing): “O.-K.-C-o-r-r—”

Billy Clanton: “Tell Wyatt the corral charges a one-minute minimum for gunfights, and we took care of the fifty-dollar deposit. Y’all can square up with us later. Now y’all don’t be late, or we’ll start without you. [Laughs.] A little gunfight humor. . . . Doc? . . . Doc?”

Doc Holliday (still writing): “S-t-a-r-t-w-i-t-h-o-u-t—”

Billy Clanton (exasperated): “Oh, whatever. We’ll see ya when we see ya.”

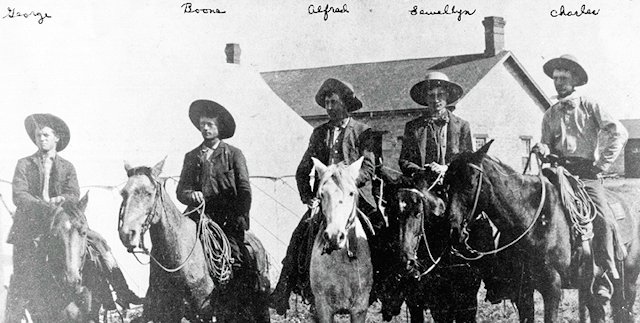

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that in 1889 the vigilante mob that ambushed four of the five Marlow brothers in Dry Creek as the Marlows and other prisoners were being transferred from the jail in Graham to the jail in Weatherford could have made all the arrangements for the ambush by telephone (photo from the Marlow Area Museum, Marlow, Oklahoma):

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that in 1889 the vigilante mob that ambushed four of the five Marlow brothers in Dry Creek as the Marlows and other prisoners were being transferred from the jail in Graham to the jail in Weatherford could have made all the arrangements for the ambush by telephone (photo from the Marlow Area Museum, Marlow, Oklahoma):

[Ring, ring.]

Vigilante 1: “Hello, Vernon? Eugene here. Listen, the ambush is on for tonight. Dry Creek. Eightish. Casual dress. We’re getting us up a good bloodthirsty mob. Everyone will be there. Sam’s wife has made the most divine matching masks for everyone in the mob to wear.”

Vigilante 2: “Masks? What color?”

Vigilante 1: “Oh! The bluest sky blue you ever did see with just the most delicate rose taupe border.”

Vigilante 2: “Cool. Blue sets off my eyes. See you there, Eugene. I’m bringing chips and dip.”

Vigilante 1: “Super! Oh, and bring some of those baby carrots. Yum!”

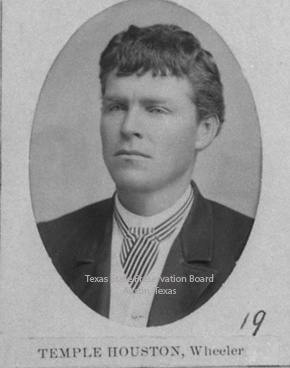

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that Sam Houston’s son Temple—instead of fatally shooting fellow lawyer Ed Jennings and injuring Ed’s brother John in a saloon in 1895 and then killing the brothers’ father, Judge J. D. Jennings, in that same saloon in 1896—could have just aired his grievances with the Jennings family by telephone (photo from Legislative Reference Library of Texas):

This incongruous overlap of tradition and technology means that Sam Houston’s son Temple—instead of fatally shooting fellow lawyer Ed Jennings and injuring Ed’s brother John in a saloon in 1895 and then killing the brothers’ father, Judge J. D. Jennings, in that same saloon in 1896—could have just aired his grievances with the Jennings family by telephone (photo from Legislative Reference Library of Texas):

[Ring, ring.]

Temple Houston: “Hello, Ed? This is Temple. Listen, you litigious louse. I don’t care for you. And I don’t care for your brother John. Or your brother Al. Or your brother Frank. And I don’t care for your old man, the judge. And while we’re at it, I don’t care for your ma. And don’t even get me started on that yappy little dog of hers.”

Ed Jennings: “Jeez, Temple. Chill. Let me put you on hold a second, and I’ll hook us all up to a conference call. That’ll save you having to call each one of us separately.”

Yes, incongruous as it may seem, Temple Houston, the Earp and Dalton brothers, Jim Courtright and Luke Short, and other latter-day pistol-packin’ hombres could have just picked up a telephone to cuss and discuss, forever changing the history of the old West. But they didn’t. And I, for one, am grateful. Because in these complicated, tech-intense times we need a simple past to cling to.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade