The year was 1889, and the world was changing. In Texas white settlers and Native Americans had lived in relative peace since 1881. People were moving to the cities. In just one more year the superintendent of the U.S. Census would declare the western frontier to be closed. Henry Ford’s Model A and the Wright brothers’ airplane were just fourteen years in the future.

But first the five Marlow brothers would bequeath to future historians a tale of the vanishing wild West, a rootin’-tootin’ tale of vigilantes, shootouts, betrayals, and severed family ties.

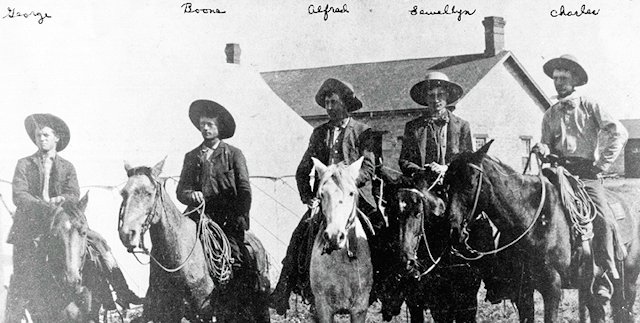

This photo is important for two reasons. First, it shows the Marlow brothers (from left, George, Boone, Alf, Epp, and Charley) in 1880. Second, it reminds us of how everyone in this story got from point A to point B: by horse. The verb go/went meant a much slower, more organic process (clip-clop, clip-clop) than it would after Henry Ford and the Wright brothers in 1903. (Photo from the Marlow Area Museum, Marlow, Oklahoma.)

This photo is important for two reasons. First, it shows the Marlow brothers (from left, George, Boone, Alf, Epp, and Charley) in 1880. Second, it reminds us of how everyone in this story got from point A to point B: by horse. The verb go/went meant a much slower, more organic process (clip-clop, clip-clop) than it would after Henry Ford and the Wright brothers in 1903. (Photo from the Marlow Area Museum, Marlow, Oklahoma.)

The Marlow brothers and their families were close. They worked together, lived together, moved together from homestead to homestead, from new start to new start (remember: clip-clop, clip-clop): Missouri, Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas. The Marlows made their living as small-scale ranchers, occasionally earning extra income by doing paid labor such as railroad grading on the Fort Worth & Denver line. They lived quietly, although in 1885, soon after family patriarch Dr. Williamson Marlow died, brother Boone killed a cowboy in Vernon, Texas. Some say the cowboy had been hired to intimidate settlers and fired at Boone first. Indeed, Boone claimed self-defense but was advised to leave town lest a jury not take his word for it.

In 1888 the Marlow clan was living in Indian Territory (Oklahoma), although brother George had gone to Colorado to visit his in-laws.

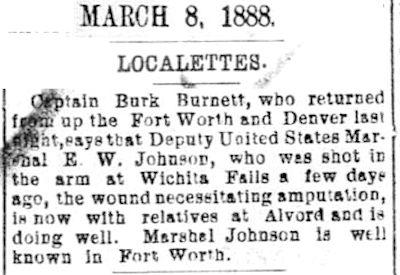

In March Samuel Burk Burnett had reported that deputy U.S. Marshal Ed Johnson, who had lost an arm to a gunshot wound, was recovering. Soon after, in Graham, Texas—home of the Northwest Federal District Court—Johnson learned that the five Marlow brothers were wanted for stealing horses from Native Americans in Oklahoma.

In March Samuel Burk Burnett had reported that deputy U.S. Marshal Ed Johnson, who had lost an arm to a gunshot wound, was recovering. Soon after, in Graham, Texas—home of the Northwest Federal District Court—Johnson learned that the five Marlow brothers were wanted for stealing horses from Native Americans in Oklahoma.

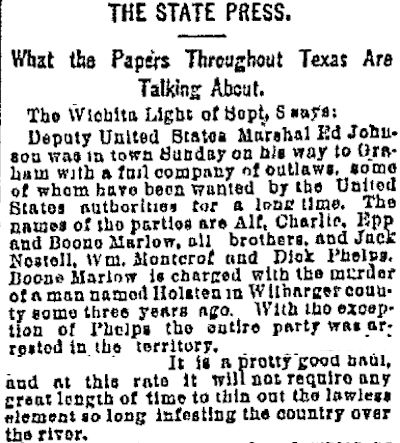

Johnson went to Oklahoma and arrested Marlow brothers Boone, Epp, Charley, and Alf and brought them back to Graham for trial. Clip is from the September 14, 1888 Dallas Morning News.

Johnson went to Oklahoma and arrested Marlow brothers Boone, Epp, Charley, and Alf and brought them back to Graham for trial. Clip is from the September 14, 1888 Dallas Morning News.

When brother George Marlow returned to Oklahoma from Colorado he was jailed briefly on orders from deputy Marshal Johnson but then released. George moved the Marlow clan (minus the four jailed brothers) to Young County (eighty miles northwest of Fort Worth) near the Brazos River south of Graham. George planned to seek the release of his four brothers from the jail in Graham. But when George went to the jail in October to see his brothers, he, too, was jailed. Now all five brothers were in jail.

The brothers quickly were indicted for stealing horses from three Native Americans in Oklahoma, although none of the three Native Americans would testify against the Marlows.

The brothers’ mother, Martha, arranged bail for her sons, and they went to work for a neighbor while awaiting trial. Meanwhile, deputy Marshal Johnson found out that Boone had killed a cowboy in Vernon and went to Vernon to get a warrant for Boone’s arrest for murder.

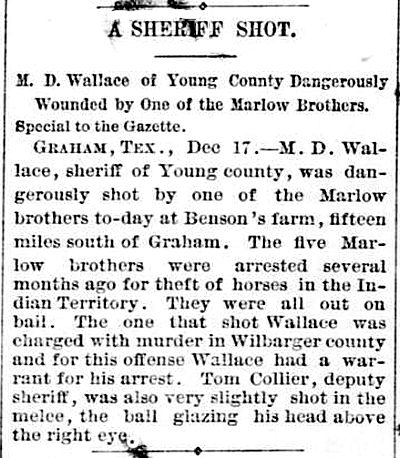

On December 17, 1888 Young County Sheriff Marion Wallace and deputy Tom Collier rode out to the Marlow cabin to arrest Boone on that murder warrant. Collier drew his pistol on Boone. Later would come the predictable conflicting accounts by eyewitnesses: Collier claimed Boone had shot first; the Marlows claimed Collier had shot first. Regardless, Boone shot Sheriff Wallace, who would die on Christmas Eve. Clip is from the December 18 Fort Worth Gazette.

On December 17, 1888 Young County Sheriff Marion Wallace and deputy Tom Collier rode out to the Marlow cabin to arrest Boone on that murder warrant. Collier drew his pistol on Boone. Later would come the predictable conflicting accounts by eyewitnesses: Collier claimed Boone had shot first; the Marlows claimed Collier had shot first. Regardless, Boone shot Sheriff Wallace, who would die on Christmas Eve. Clip is from the December 18 Fort Worth Gazette.

Brother Epp Marlow rode to Graham to fetch a doctor for Sheriff Wallace and was arrested. Deputy Collier rode back to Graham and returned with a posse to arrest Charley Marlow. Boone Marlow had disappeared before the posse arrived.

Brothers George and Alf had not been at the cabin at the time of the shooting, but they, too, were soon arrested and jailed in Graham. That left only Boone at large. He was charged with murder, the four jailed brothers with complicity.

While Boone remained a fugitive with a price on his head, from their jail cell the four other brothers overheard talk of lynching. Sheriff Wallace had been well liked. Although Boone alone had shot the sheriff, the other brothers feared for their lives as well.

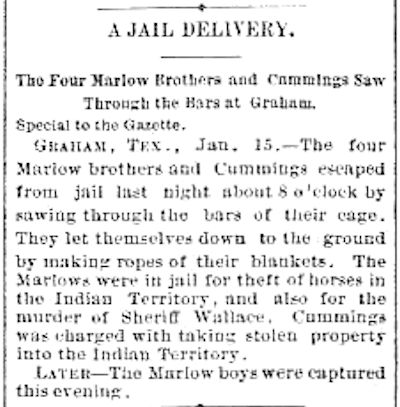

So, on January 14, 1889 the four brothers obtained a knife or a saw from another prisoner and began hacking through the wall of their jail cell. Soon they were free men again.

So, on January 14, 1889 the four brothers obtained a knife or a saw from another prisoner and began hacking through the wall of their jail cell. Soon they were free men again.

Briefly. As they headed back to the Marlow cabin they were recaptured. Clip is from the January 16 Gazette. (In the headline a “delivery” was a liberation from jail.)

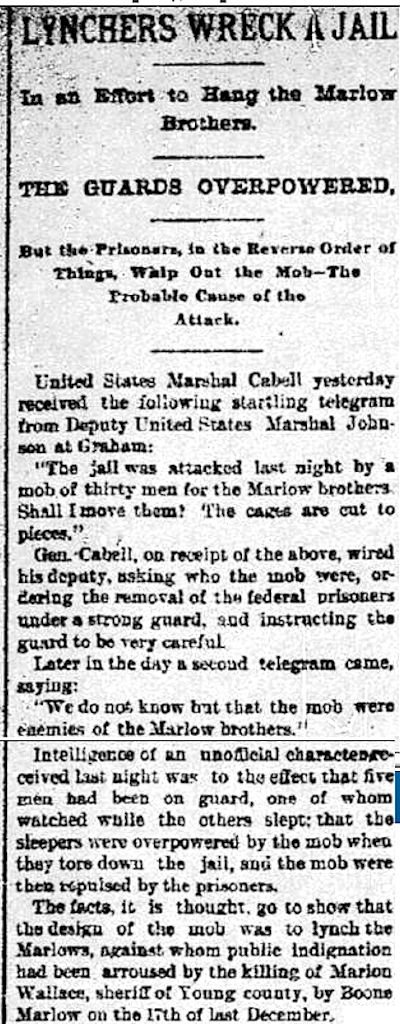

On January 17, 1889, one month after the shooting of Sheriff Wallace, a vigilante mob of thirty men overpowered guards at the Graham jail and attempted to spring the four Marlow brothers in order to lynch them. The brothers respectfully declined the offer of freedom and, armed with makeshift weapons, drove out the mob. The Marlow brothers claimed that the mob included jail guards and the county attorney.

On January 17, 1889, one month after the shooting of Sheriff Wallace, a vigilante mob of thirty men overpowered guards at the Graham jail and attempted to spring the four Marlow brothers in order to lynch them. The brothers respectfully declined the offer of freedom and, armed with makeshift weapons, drove out the mob. The Marlow brothers claimed that the mob included jail guards and the county attorney.

In light of the facts that the lynch mob had damaged the jail and that the mood in Graham was ugly, U.S. Marshal William Lewis Cabell ordered that the jail’s prisoners be moved to the jail in Weatherford. (Cabell in 1874 had been the first of three Cabells to be elected mayor of Dallas.) Clip is from the January 19 Dallas Morning News.

And so it was that two nights later, working in the dark for maximum secrecy, deputy Marshal Johnson readied two wagons and a buggy—what today would be called a “convoy.” The convoy included six prisoners and seven guards, including Johnson and Marion A. (“Little Marion”) Wallace, nephew of the slain sheriff. The guards were heavily armed, and one wagon carried extra weapons and ammunition. The six prisoners were George and Epp Marlow (shackled together), Alf and Charley Marlow (shackled together), and Lewis Clift and William Burkhart (shackled together).

As the convoy left the Graham jail, several residents of town were on hand to watch. So much for secrecy! Furthermore, the Marlows recognized one of the convoy guards: Phlete Martin, county attorney, had been in the mob who had attacked the jail. For this reason the Marlows suspected they were being set up as they headed to Weatherford.

Sure enough, two miles east of Graham on the Weatherford Road the convoy slowed as it crossed Dry Creek (remember: clip-clop, clip-clop).

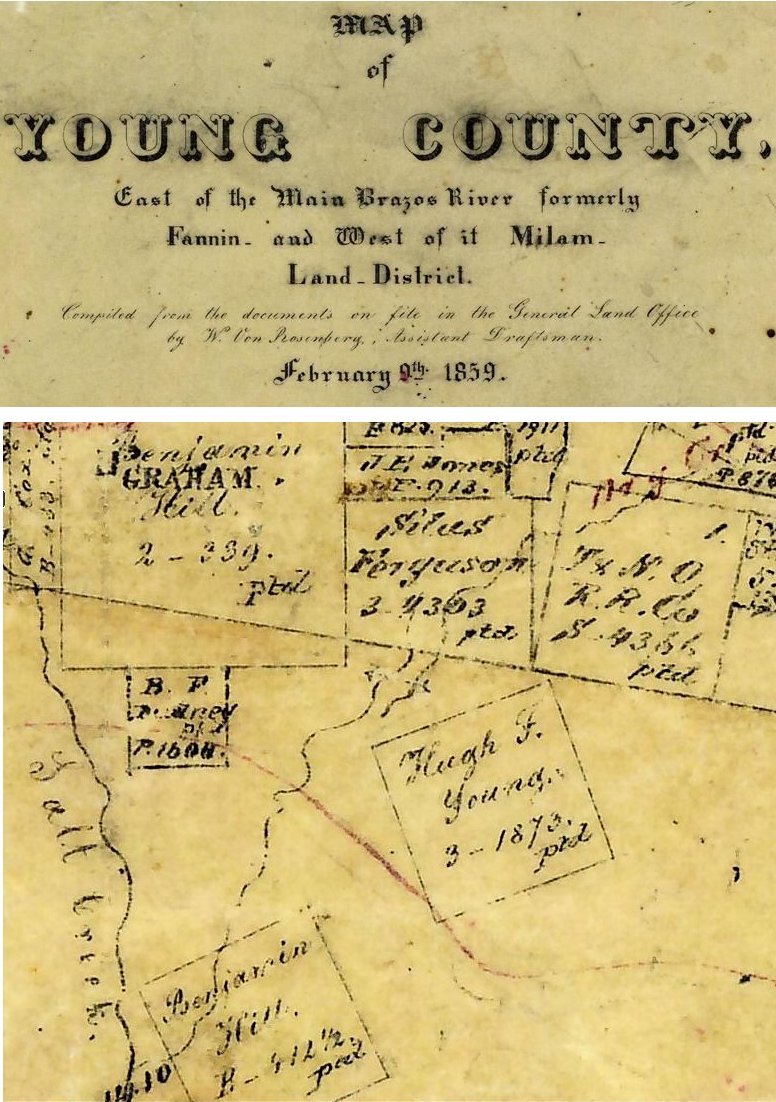

Texas General Land Office map of 1859 shows Graham in upper left. Dry Creek runs from upper right southwest to Salt Creek.

Texas General Land Office map of 1859 shows Graham in upper left. Dry Creek runs from upper right southwest to Salt Creek.

Suddenly masked men—variously estimated at fifteen to forty—appeared on the left side of the road beside the convoy.

Suddenly masked men—variously estimated at fifteen to forty—appeared on the left side of the road beside the convoy.

George Marlow later testified that one of the ambushers shouted, “Hold up! Hold up!”

Marlow said one of the guards in the convoy responded likewise: “Hold up!”

The convoy held up.

Marlow said Phlete Martin, one of the convoy guards, shouted, “Here they are; take all six of the sons of bitches.”

And then the shooting began.

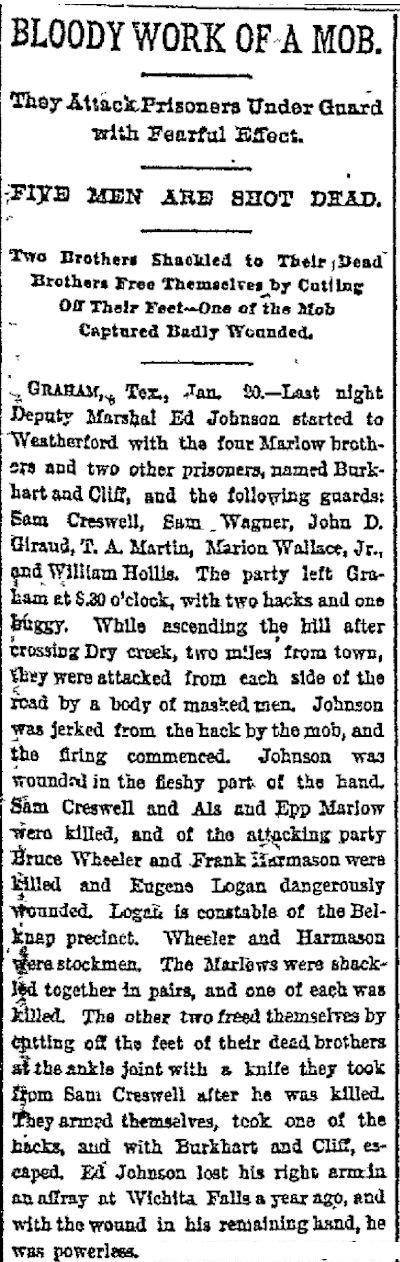

George Marlow later said some of the guards threw their weapons to the ambushers. Some of the guards may have fled. Some may have joined the ambushers in their attack on the prisoners. The New York Sun reported that the guards fired over the heads of the ambushers. The four Marlow brothers, being shackled (George to Epp, Alf to Charley), could not flee. But as the shooting began they did manage to reach the wagon carrying the spare guns. The four Marlows fired back at the bushwhackers. But in the fusillade, Epp and Alf were quickly killed, leaving George and Charley each shackled to a dead brother and more handicapped than ever.

George and Charley, themselves wounded, continued to fight off the mob until its members retreated. Two Marlows, one guard, and two ambushers were dead. One-armed deputy Marshal Johnson was wounded, as were several others. The New York Sun reported that more than two hundred shots had been fired. Clip is from the January 21 Dallas Morning News.

Dry Creek was quiet again except for the moaning.

Dry Creek was quiet again except for the moaning.

In 1946 the son of deputy Marshal Johnson retold the tale in the Dallas Morning News. Clip is from October 29.

The gunfire at an end, George Marlow found a knife on the dead guard’s body, and George and Charley grimly severed the ties that bind: They freed themselves from their dead brothers by cutting off the shackled foot of each dead brother. Charley recalled the grisly scene in 1890. Clip is from the November 18 Dallas Morning News.

The gunfire at an end, George Marlow found a knife on the dead guard’s body, and George and Charley grimly severed the ties that bind: They freed themselves from their dead brothers by cutting off the shackled foot of each dead brother. Charley recalled the grisly scene in 1890. Clip is from the November 18 Dallas Morning News.

George and Charley then drove one of the convoy wagons back to the Marlow family cabin south of Graham and hunkered down, anticipating the next onslaught from now-Sheriff Collier. But George and Charley said they would surrender only to a U.S. marshal or deputy. So, U.S. Marshal Cabell sent two deputy marshals: W. H. Morton and Cabell’s son Ben (second Cabell mayor of Dallas and father of Earle, third Cabell mayor of Dallas) to arrest George and Charley. The two brothers were taken to jail in Dallas to be held as witnesses to the mob actions. Clip is from the January 22, 1889 Gazette.

George and Charley then drove one of the convoy wagons back to the Marlow family cabin south of Graham and hunkered down, anticipating the next onslaught from now-Sheriff Collier. But George and Charley said they would surrender only to a U.S. marshal or deputy. So, U.S. Marshal Cabell sent two deputy marshals: W. H. Morton and Cabell’s son Ben (second Cabell mayor of Dallas and father of Earle, third Cabell mayor of Dallas) to arrest George and Charley. The two brothers were taken to jail in Dallas to be held as witnesses to the mob actions. Clip is from the January 22, 1889 Gazette.

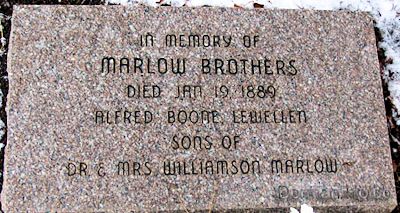

After the ambush, mother Marlow had her sons Epp and Alf (the two killed in the ambush) buried in a shared grave at Finis Cemetery, southeast of Graham in Jack County.

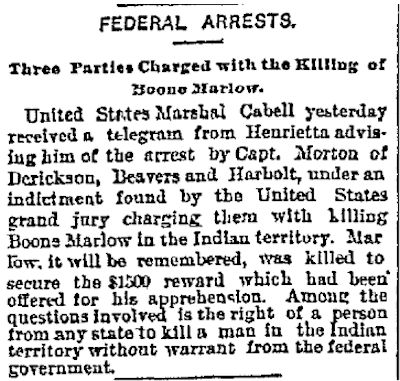

That leaves one Marlow brother unaccounted for. Boone. On January 29, 1889 three bounty hunters brought the body of Boone Marlow to Graham to claim a $1,500 ($40,000 today) reward on his head. The three claimed that Boone had resisted arrest. Clip is from the January 30 Gazette.

That leaves one Marlow brother unaccounted for. Boone. On January 29, 1889 three bounty hunters brought the body of Boone Marlow to Graham to claim a $1,500 ($40,000 today) reward on his head. The three claimed that Boone had resisted arrest. Clip is from the January 30 Gazette.

Ah, but an autopsy showed that Boone had been poisoned and his corpse shot to support the bounty hunters’ claim that he had resisted arrest. The bounty hunters (one of them the brother of Boone’s girlfriend) were charged with murder and convicted. Clip is from the February 17, 1889 Dallas Morning News.

Ah, but an autopsy showed that Boone had been poisoned and his corpse shot to support the bounty hunters’ claim that he had resisted arrest. The bounty hunters (one of them the brother of Boone’s girlfriend) were charged with murder and convicted. Clip is from the February 17, 1889 Dallas Morning News.

And thus brother Boone was added to the grave of Epp and Alf in the Finis Cemetery, making the grave a triplex. This tombstone is a modern replacement. The original grave marker was a slab of sandstone on which the Boone women carved an inscription: “Alfred and Boone and Elly Marlow waz mobed January the 19, 1889 age 20 [next age is illegible] 22.”

And thus brother Boone was added to the grave of Epp and Alf in the Finis Cemetery, making the grave a triplex. This tombstone is a modern replacement. The original grave marker was a slab of sandstone on which the Boone women carved an inscription: “Alfred and Boone and Elly Marlow waz mobed January the 19, 1889 age 20 [next age is illegible] 22.”

The cemetery is all that is left of the town of Finis, and finis, of course, is Latin for “the end.”

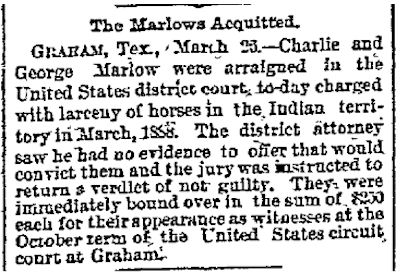

But wait! The little cemetery at Finis was the end of only three Marlow brothers. That still leaves two brothers. On March 25, 1889 George and Charley, who survived the ambush at Dry Creek, were tried for horse theft and acquitted. Clip is from the March 27 Dallas Morning News.

But wait! The little cemetery at Finis was the end of only three Marlow brothers. That still leaves two brothers. On March 25, 1889 George and Charley, who survived the ambush at Dry Creek, were tried for horse theft and acquitted. Clip is from the March 27 Dallas Morning News.

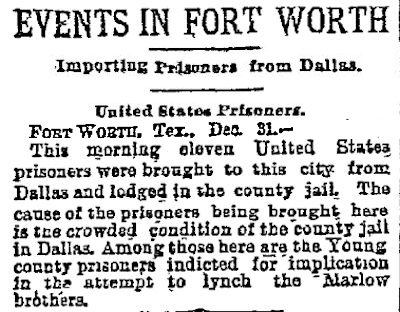

Then the law turned its attention to the mob or mobs who had attacked the jail and ambushed the convoy. Seven men were indicted for conspiracy and murder and held in the Dallas jail awaiting trial in Graham. One of the men indicted was “Little Marion” Wallace, nephew of the slain sheriff. “Little Marion” had been one of the men guarding the prisoners at Dry Creek.

On the final day of 1890—the year the western frontier had been declared closed—the Dallas jail was so full that eleven prisoners, including the Dry Creek Seven, were transferred to the county jail in Fort Worth. Clip is from the January 1, 1891 Dallas Morning News.

On the final day of 1890—the year the western frontier had been declared closed—the Dallas jail was so full that eleven prisoners, including the Dry Creek Seven, were transferred to the county jail in Fort Worth. Clip is from the January 1, 1891 Dallas Morning News.

On trial in Graham, on April 17, 1891 three of the Dry Creek Seven defendants, including “Little Marion” Wallace, were found guilty of conspiracy but not guilty of murder. The other four defendants were acquitted. The three who were found guilty were sentenced to ten years in prison, but their lawyers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court in 1892 set aside the verdict and ordered a new trial. That new trial never came. None of the Dry Creek Seven served prison time. Clip is from the April 18 Dallas Morning News.

On trial in Graham, on April 17, 1891 three of the Dry Creek Seven defendants, including “Little Marion” Wallace, were found guilty of conspiracy but not guilty of murder. The other four defendants were acquitted. The three who were found guilty were sentenced to ten years in prison, but their lawyers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court in 1892 set aside the verdict and ordered a new trial. That new trial never came. None of the Dry Creek Seven served prison time. Clip is from the April 18 Dallas Morning News.

On September 11, 1891 the Dallas Morning News described a grisly relic in the U.S. marshal’s office in Dallas: the stone on which the Marlow brothers George and Charley had severed family ties after the ambush at Dry Creek.

On September 11, 1891 the Dallas Morning News described a grisly relic in the U.S. marshal’s office in Dallas: the stone on which the Marlow brothers George and Charley had severed family ties after the ambush at Dry Creek.

George and Charley—the two surviving Marlow brothers—were defendants or plaintiffs in a few more legal cases. (In 1891 Texas Rangers Captain Bill (“one riot, one Ranger”) McDonald and Grude Britton—a future Fort Worth saloon operator—would go to Colorado to arrest Charley as an accessory in the murder of Sheriff Wallace. Legal technicalities would stymie the two Rangers.) The Marlow family collected some money from lawsuits claiming wrongful injuries and deaths and moved to Colorado (remember: clip-clop, clip-clop).

The fact that the acts by and upon the Marlow brothers were resolved not by lynchings but rather by court cases and jail sentences shows that the lawless West was slowly, grudgingly becoming the lawful West. In Colorado George and Charley started over and lived quiet, even productive lives. The two brothers even served as lawmen. After 1903 maybe they even drove a Model A or flew in an airplane.

The world was changing.

When George and Charley Marlow died in the 1940s they had outlived the wild West by a half-century.

The movie The Sons of Katie Elder is loosely based on the Marlow brothers.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Hi

Charles Marlow was my great grampa. His daughter (Georgia) with wife Emma

was my grandma. Her daughter Alice Couchman-Page was my mother. She just passed away in 2019 at 100 yrs of age. I have heard stories of Grampa Charley since I was little and now my children and grandchildren are loving to hear them.

Mom (Alice) lived with Charles and Emma for many years when her mother Georgie was working.

Kay Sloan: I have many letters from you to my mother from when you two were sharing family histories.

Really still enjoy re- reading the stories in print like this one.

Linda Page Shaw

Hi Linda,

My name is Dan Bull. I am going through family history, and I found Joseph Crawford, Elizabeth Rachel Attebury, and Cora Peahen Marlow, along with John Allen Marlow and Nancy. Joseph was my grandmother, grandmother. I have many photos and documents, even a letter written to C.C. Barrow, intercepted by Under Sherriff D.A. Marlow. It was written by Jodie Davis to the Oats girls and thrown out the jail window. Its mentions Bonnie as well.

If you want to reach out to me, let me know. Thanks [email protected] Best, Dan

Very well told and researched.

Thank you, Andrew. It’s a great episode in our western history.

Thank you very much for this writing of the Marlow Brothers. I look forward to visiting the historical museum in Graham. I visited the gravesite in Finis as a young woman and want to re-visit to see the new gravestone. I do hope the original Tombstone was saved.

Thank you, Dawn. The original stone may be at the Marlow museum.

This is a very good writing of the Marlow Brothers. We are starting a historical museum in Graham, TX and would like to feature items about the brothers. Any other information would be appreciated. You did a great job.

Thank you so much. It’s a great story of the old West. Good luck with your museum. The Marlow museum in Oklahoma can be contacted.

I believe I may have one of their Winchester’s and trying omg to find out some information on it.

All I can suggest is the Marlow Area Museum. I can’t find a website or e-mail address:

Marlow Area Museum

127 W Main St

Marlow, OK 73055

Phone: 580-658-2212

Cheyenne,

I saw your post from 2/21/19 about the Marlow Brothers. If you have any knowledge or artifacts, we are starting a historical museum in Graham, Tx and would love to visit with you.

I was born and raised in Colorado. George was my great grandfather. My grandmother, his daughter, lived to 102 years old. My mother recently passed away at 94. I Thank You for taking the time to put this out. I am truly honored to be a part of this family. I would be happy to forward you any information that I have, as there are a few articles that have been passed down. Once again, Thank You for keeping the stories alive.

George is my 4×great uncle, his sister Charlotte is my 4×great grandmother, I just discovered all this a few years ago

I guess you and I are related. My great grandfather was Oran Faulk Marlow, brother of Dr.

Marlow. He did not stay with the Marlow family, Oran remained in Tennessee and later moved into Kentucky. My grandmother was the into Kentucky! Have done a lot of genealogy on the Marlow family!

Thank You for this article. E.D Johnson was my great grandfather. My Grandmother Emma was his daughter. My brother Herb has his badge.I am going to Graham this week, my first trip to the area my mom and grandmother came from. I heard many stories from my grandmother about growing up in Graham and about Mr. Johnson. I plan on visiting Dry Creek area and the jail if it is still standing. Thank you, Ralph

Thank you, Mr. Zimmerman. Your great-grandfather played a featured role in one heck of a Texas tale.

Census listings place Charles Marlow in Los Angeles (Glendale) in 1930. As we all know, Wyatt Earp was in Los Angeles in his later years (1920 census, LA District 61, neighboring Glendale).

I can’t help but ponder the possibility that the two may have met circa 1925-ish to share ‘war stories’n on movie sets with William Hart and Tom Mix.

Amazing to think of the changes that their generation saw.

My great grandfather was “Little Marion” Wallace.

I have the gun and holster that he was wearing at the shootout

Wow! What a great relic of sure-nuff wild West history.

Charlie Marlow was my second great grandfather. I really enjoyed this article and the newspaper clippings. Thank you.

Thanks, David. Heck of a wild West story.

Hi David,

Read you comment and want to tell you that you and I are related. Dr. Wilson Williamson Marlow was the brother of my second great Grnadfather, Oran Faulk Marlow. I have worked on the genealogy of our Marlows since 1969. Have never put it down. I live in Texas and for many years I did a reunion in Marlow, OK. Any person who was related to the Marlow family was invited. It was wonderful. One year we had 4 men named William Marlow. Where do you live? Hope to hear from you.

Thank you very much for this article, and the links. Authentication via news-clippings is fantastic. I could explore here all day.

Thanks, Bill. I hope the clips help to make these posts more relevant. What is history to us was at one time today’s news to our ancestors.

HA! Your post is dated 12/29/15. Next day, 12/30/15, I watched (once again) The Sons Of Katie Elder. Did a Google search, hit the Wiki link, discovered movie was based (loosely) on a true story occurring in Texas.

After doing some research, I am now of the opinion that the Marlow brothers are right up there with the Earp brothers.

Interestingly, Charles Marlow made his way to L.A., same place Wyatt was, same time frame. I’d bet they swapped a few stories around the Hollywood lots, eh?

Those two men indeed lived long enough to see a much-changed world. My parents could have known Wyatt Earp! There’s more on Fort Worth’s links to the Earp boys at O.K. Corral: 5 Cowboys, 4 Lawmen, 1 Brother Who Said, “I . . . Can Hang Them” and Footloose: Drifting Along with Tumblin’ “Uncle Bob” Winders.