On January 12, 1911 a crowd estimated at fifteen thousand gathered at Fort Worth’s driving park to witness a changing world.

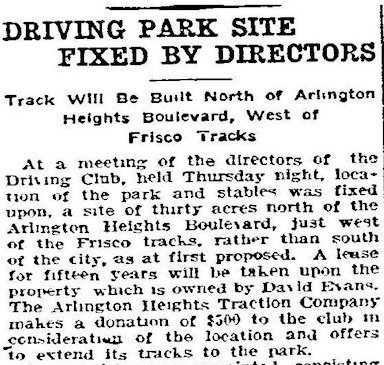

Some background: The driving park had opened in 1905 north of City Park (now “Trinity Park”) and north of where the Montgomery Ward store would be built in 1928. In 1905 West 7th Street was still called “Arlington Heights Boulevard.” Clip is from the September 22 Telegram.

Some background: The driving park had opened in 1905 north of City Park (now “Trinity Park”) and north of where the Montgomery Ward store would be built in 1928. In 1905 West 7th Street was still called “Arlington Heights Boulevard.” Clip is from the September 22 Telegram.

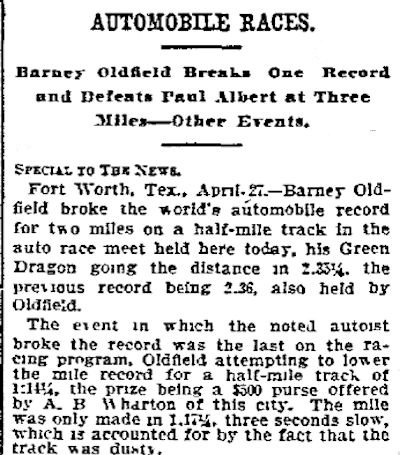

From its beginning the driving park was a showcase of technological innovation. The driving park was 1905’s version of Texas Motor Speedway. In 1906 daredevil autoist Barney Oldfield set a world auto speed record for two miles at the driving park, averaging just under sixty miles per hour. (Thirty years later Oldfield would be back in town as official greeter at the Frontier Centennial.) Note that a $500 purse was offered by A. B. Wharton, the man of the house at Thistle Hill. Wharton opened one of Fort Worth’s first “auto liveries.” Clip is from the April 28 Dallas Morning News.

From its beginning the driving park was a showcase of technological innovation. The driving park was 1905’s version of Texas Motor Speedway. In 1906 daredevil autoist Barney Oldfield set a world auto speed record for two miles at the driving park, averaging just under sixty miles per hour. (Thirty years later Oldfield would be back in town as official greeter at the Frontier Centennial.) Note that a $500 purse was offered by A. B. Wharton, the man of the house at Thistle Hill. Wharton opened one of Fort Worth’s first “auto liveries.” Clip is from the April 28 Dallas Morning News.

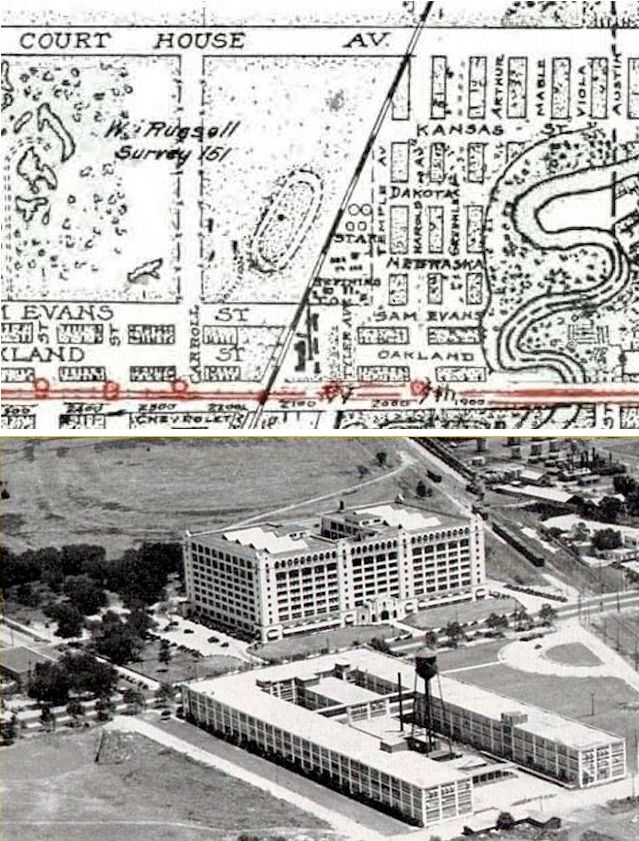

The oval track of the driving park appears on the 1920 Rogers city map. (Court House Avenue became “White Settlement Road.”) In 1930 part of the oval could still be seen behind the Montgomery Ward building in a photo that appeared in the TCU yearbook. The U-shaped building in the foreground is the 1916 Chevrolet plant. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM”; yearbook scan by Pete Charlton.)

The oval track of the driving park appears on the 1920 Rogers city map. (Court House Avenue became “White Settlement Road.”) In 1930 part of the oval could still be seen behind the Montgomery Ward building in a photo that appeared in the TCU yearbook. The U-shaped building in the foreground is the 1916 Chevrolet plant. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM”; yearbook scan by Pete Charlton.)

Like an earlier driving park on Samuels Avenue, the driving park on West 7th Street offered more than just equine events (polo, horse shows, riding and racing): It offered baseball, tennis, rodeo, motorcycle races, auto races, shooting contests, casting contests, baby contests, even a head-on collision of two steam locomotives. In fact, on January 12, 1911 the people in the crowd at the driving park, who were probably still getting accustomed to seeing gas-powered machines on the roads, gathered to witness something even more astounding: gas-powered machines in the air.

Like an earlier driving park on Samuels Avenue, the driving park on West 7th Street offered more than just equine events (polo, horse shows, riding and racing): It offered baseball, tennis, rodeo, motorcycle races, auto races, shooting contests, casting contests, baby contests, even a head-on collision of two steam locomotives. In fact, on January 12, 1911 the people in the crowd at the driving park, who were probably still getting accustomed to seeing gas-powered machines on the roads, gathered to witness something even more astounding: gas-powered machines in the air.

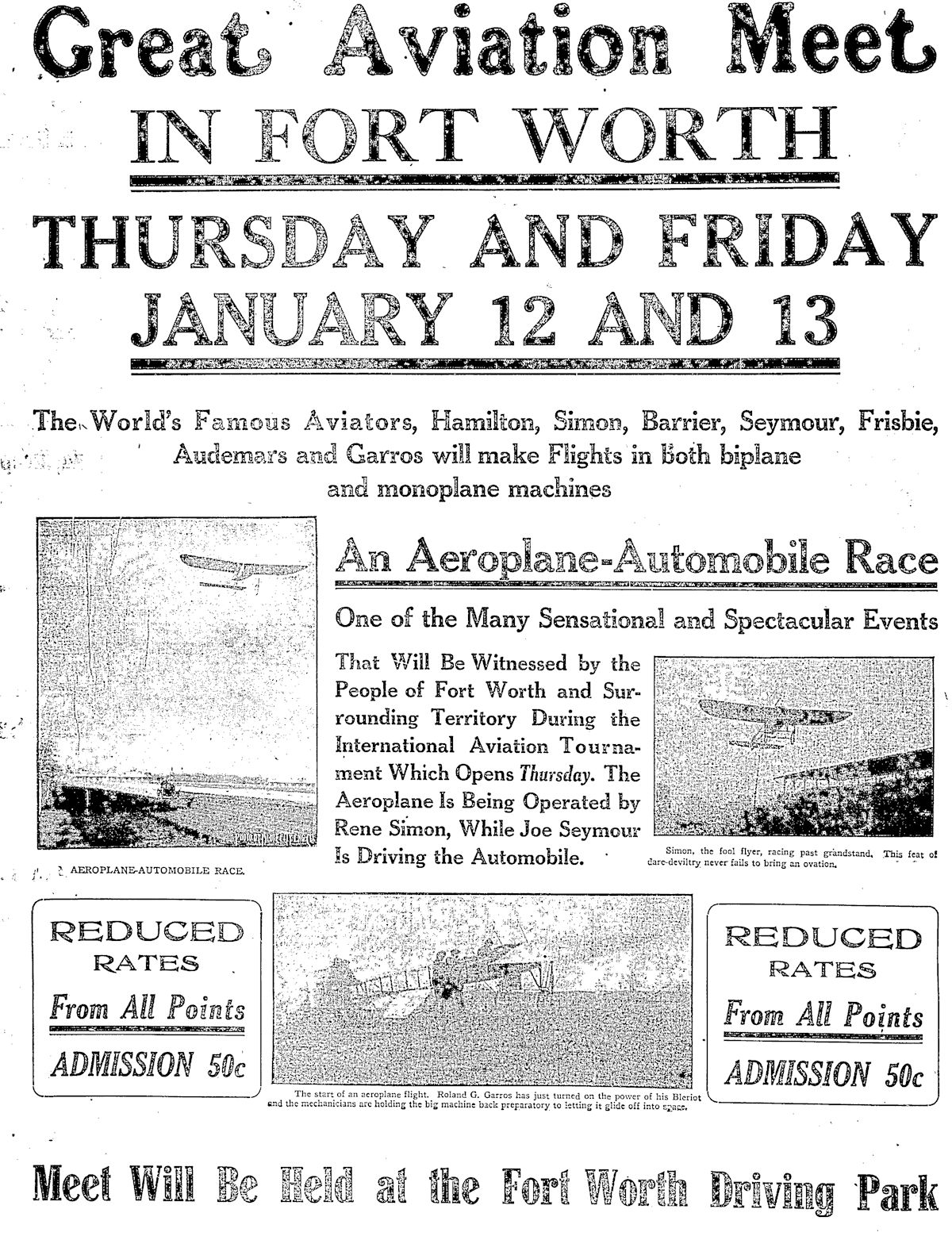

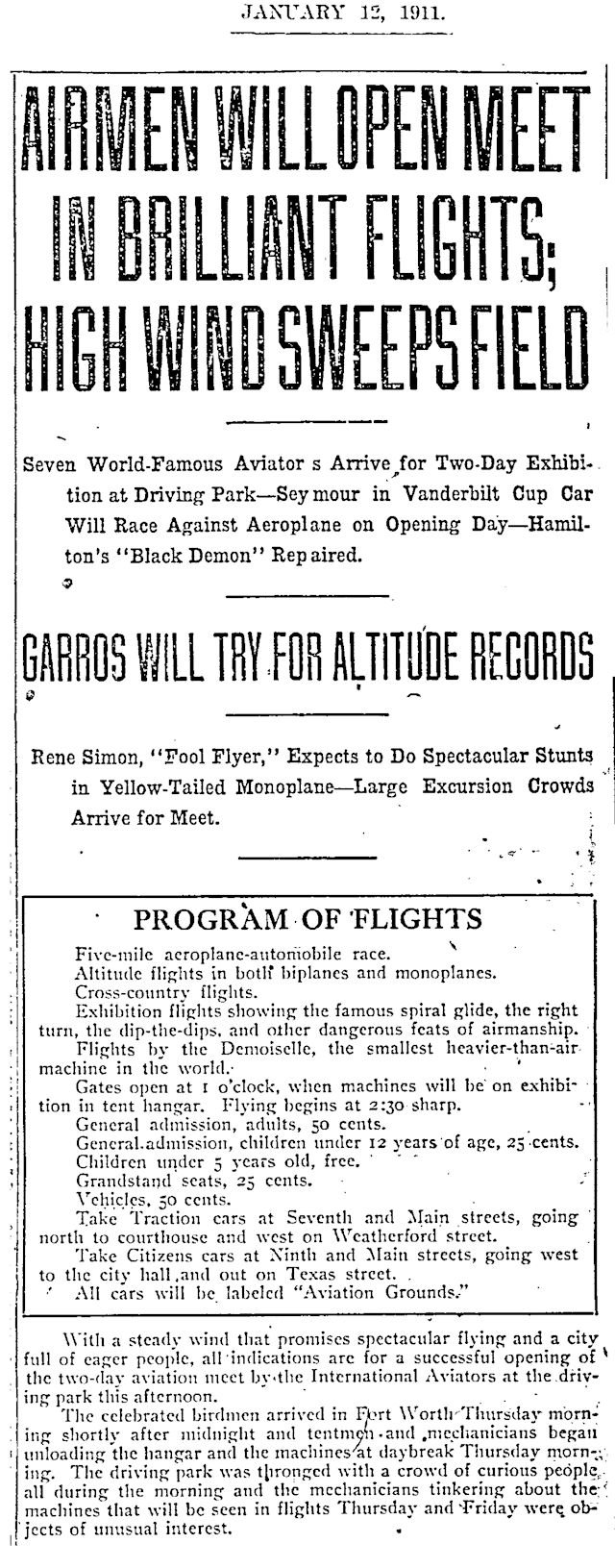

An international team of aviation pioneers would defy death and gravity during the Great Aviation Meet. Team members included Edmond Audemars (Swiss) and Rene Simon, Rene Barrier, and Roland Garros (French), who would make flights in both biplanes and monoplanes, including a Demoiselle (French for “damselfly” or “small crane”), “the smallest heavier-than-air machine in the world” (weight: 243 pounds). Another highlight would be an air-ground race between two members of the team: Simon (the “fool flyer”) flying an airplane and American Joe Seymour driving a Fiat car. Full-page ad is from the January 12 Star-Telegram.

Among those Fort Worthians who had worked to bring the Great Aviation Meet to town was Star-Telegram secretary and business manager Amon Carter. The editorial page on January 12 helped readers appreciate the difference between a monoplane and a biplane in terms Cowtowners could relate to, calling the monoplane a “shorthorn” and the biplane a “longhorn.”

Among those Fort Worthians who had worked to bring the Great Aviation Meet to town was Star-Telegram secretary and business manager Amon Carter. The editorial page on January 12 helped readers appreciate the difference between a monoplane and a biplane in terms Cowtowners could relate to, calling the monoplane a “shorthorn” and the biplane a “longhorn.”

Carter, an early proponent of aviation, would be instrumental in bringing lots more airplanes to Fort Worth, first with Camp Taliaferro, then Texas Air Transport (now “American Airlines”), and then the bomber plant and Tarrant Field (later “Carswell Air Force Base”).

Local advertisers tailored their ads to the air show. “Our profits are up in the air on winter underwear,” said Jamieson and Miller menswear store in the Worth Hotel.

Local advertisers tailored their ads to the air show. “Our profits are up in the air on winter underwear,” said Jamieson and Miller menswear store in the Worth Hotel.

Many employers gave workers a half-day off to attend the air show. The flying circus performed in several Texas cities to big crowds: 5,000 spectators in Temple, 8,000 in Waco, 20,000 in Dallas, 25,000 in El Paso, 25,000 in Houston. On January 9 in El Paso, the Morning Times there reported, Rene Simon and Roland Garros were forced to take off from Washington Park “to escape having their machines taken apart piecemeal as souvenirs” by “the big crowd, going wild with enthusiasm.” A similar incident occurred in Houston.

Many employers gave workers a half-day off to attend the air show. The flying circus performed in several Texas cities to big crowds: 5,000 spectators in Temple, 8,000 in Waco, 20,000 in Dallas, 25,000 in El Paso, 25,000 in Houston. On January 9 in El Paso, the Morning Times there reported, Rene Simon and Roland Garros were forced to take off from Washington Park “to escape having their machines taken apart piecemeal as souvenirs” by “the big crowd, going wild with enthusiasm.” A similar incident occurred in Houston.

It’s no wonder the crowds were huge. This was sure-’nuff derring-do by jaunty young men who were making it up as they went along. Obviously in 1911 no one had a lot of experience in flying. The primitive airplanes, like their pilots, were unproven. High wind could blow a small, underpowered plane off course or into the ground. The pilots navigated largely by sight. Roland Garros, best remembered of those pioneer aviators who flew in the Great Aviation Meet at Fort Worth, had gotten lost in the clouds at the Dallas show and would be overtaken by darkness at the Houston show and forced to land ten miles away from where he took off.

So heavy was attendance on the first day of the Fort Worth show that a traffic jam on the bridge over the Trinity River stopped streetcar traffic on Arlington Heights Boulevard.

So heavy was attendance on the first day of the Fort Worth show that a traffic jam on the bridge over the Trinity River stopped streetcar traffic on Arlington Heights Boulevard.

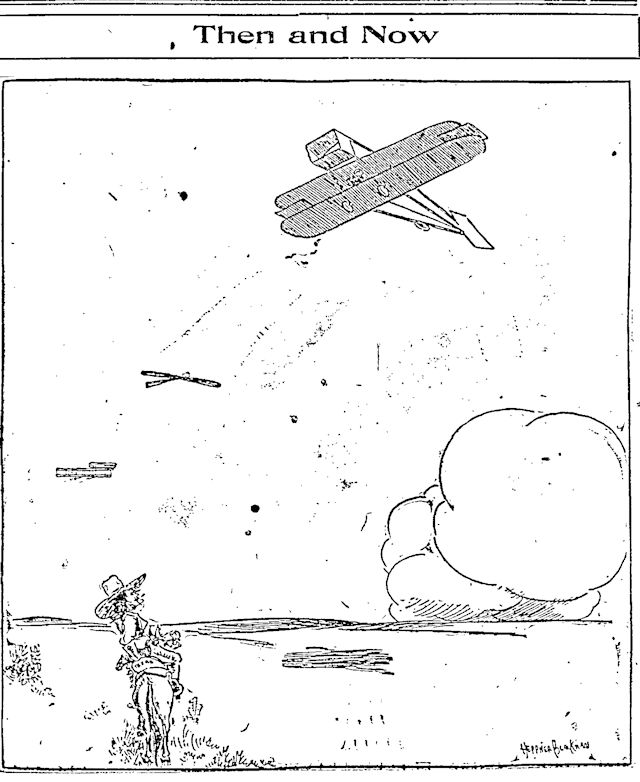

Star-Telegram cartoonist Heppner Blackman recognized that change was in the air.

Star-Telegram cartoonist Heppner Blackman recognized that change was in the air.

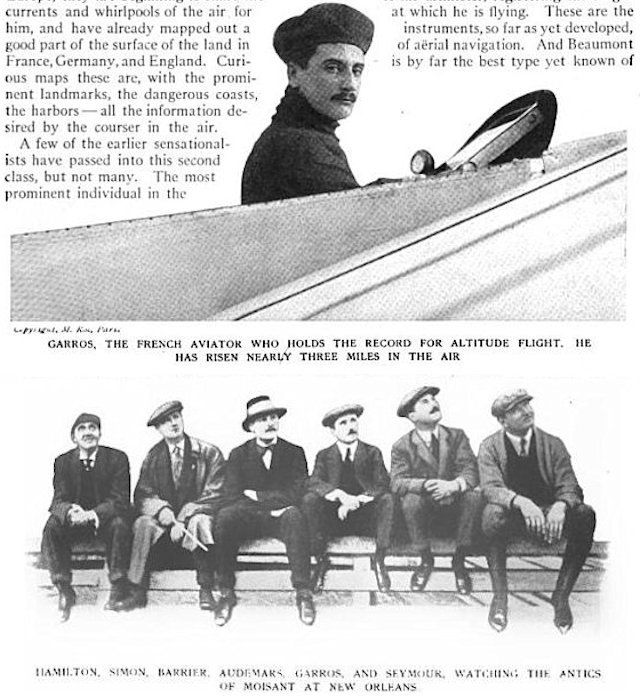

In 1912 McClure’s Magazine printed a feature on the stars of the Great Aviation Meet of 1911. “Moisant” was John B. Moisant, “king of aviators,” who was killed two weeks before the Fort Worth air show when his plane crashed in New Orleans during the Michelin Cup flight competition.

In 1912 McClure’s Magazine printed a feature on the stars of the Great Aviation Meet of 1911. “Moisant” was John B. Moisant, “king of aviators,” who was killed two weeks before the Fort Worth air show when his plane crashed in New Orleans during the Michelin Cup flight competition.

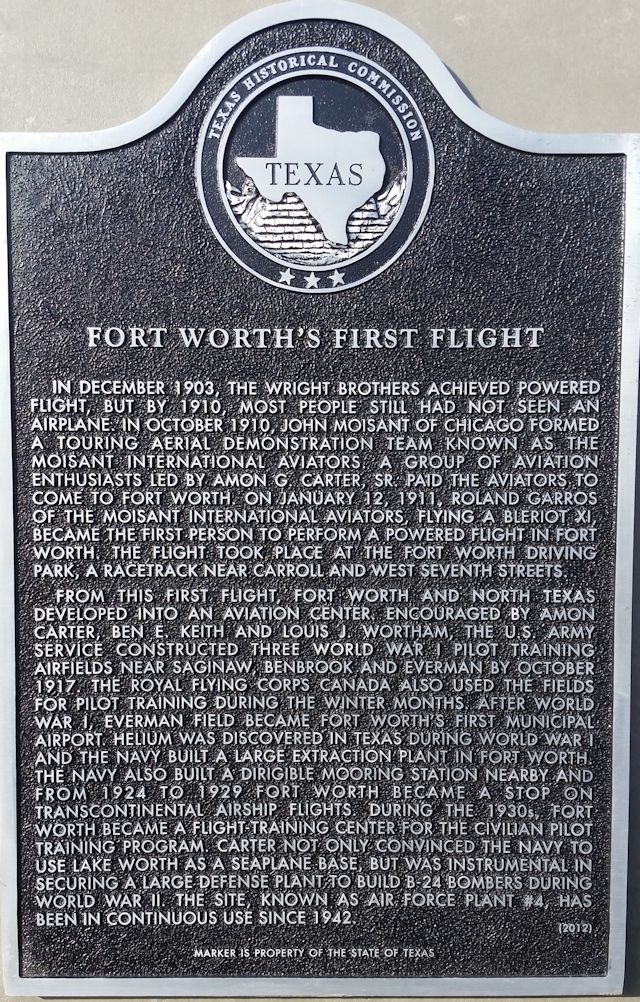

Roland Garros is credited with making the first powered flight from Fort Worth on January 12, 1911 in his Bleriot XI Statue of Liberty monoplane. (Photo of a Bleriot XI from Wikipedia.)

Roland Garros is credited with making the first powered flight from Fort Worth on January 12, 1911 in his Bleriot XI Statue of Liberty monoplane. (Photo of a Bleriot XI from Wikipedia.)

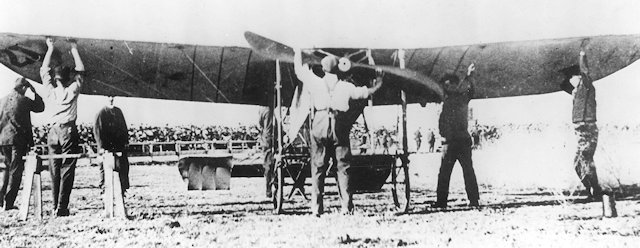

The other pilots in the flying troupe had refused to fly their flimsy planes that day because of winds of twenty-five miles per hour. But Garros did not want to disappoint the crowd, who had been waiting for four hours to see his flying machine in action. He stared down the wind and went up in his monoplane, leveled off at twenty-one hundred feet, and flew ten miles in seven minutes over the North Side.

The other pilots in the flying troupe had refused to fly their flimsy planes that day because of winds of twenty-five miles per hour. But Garros did not want to disappoint the crowd, who had been waiting for four hours to see his flying machine in action. He stared down the wind and went up in his monoplane, leveled off at twenty-one hundred feet, and flew ten miles in seven minutes over the North Side.

Clip is from January 13.

Clip is from January 13.

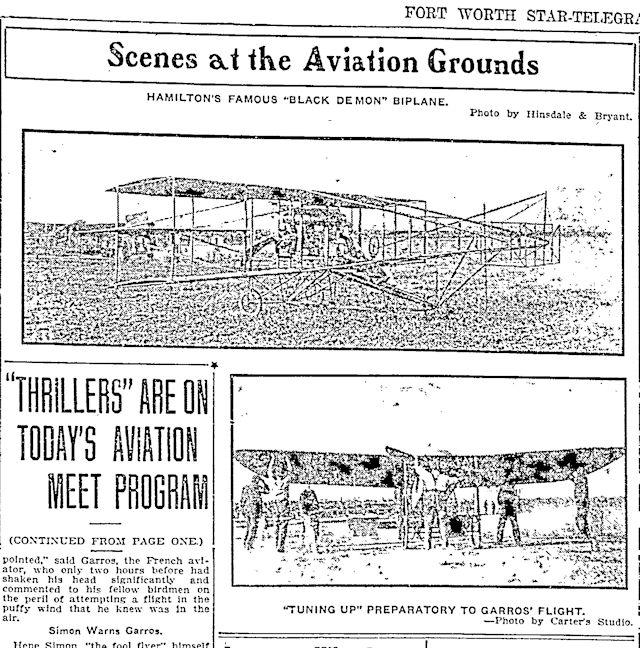

The Bleriot XI of Roland Garros. (Photo from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

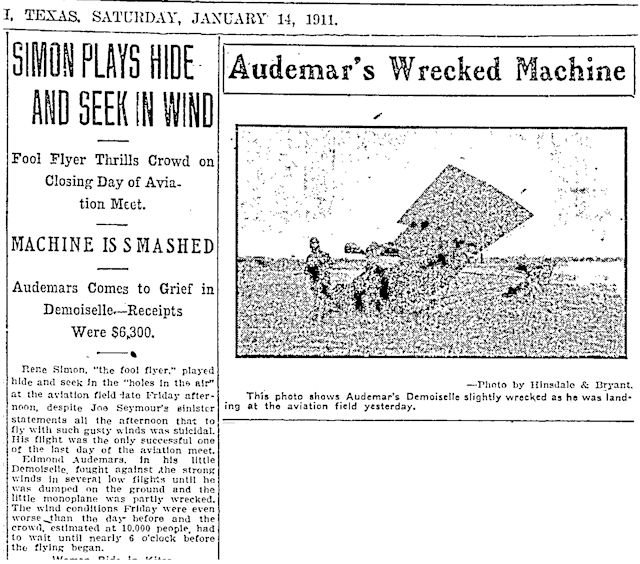

On the second and final day of the meet, wind was even more of a problem than it had been on the first day. But Rene Simon (the “fool flyer”) got his monoplane into the air, circled the driving park twice (even as his engine stopped once in midflight), and flew “only a few feet above the heads” of those in the crowd at the park. Edmond Audemars’s airplane was airborne only briefly and was damaged while landing.

On the second and final day of the meet, wind was even more of a problem than it had been on the first day. But Rene Simon (the “fool flyer”) got his monoplane into the air, circled the driving park twice (even as his engine stopped once in midflight), and flew “only a few feet above the heads” of those in the crowd at the park. Edmond Audemars’s airplane was airborne only briefly and was damaged while landing.

Roland Garros would go on to set speed and altitude records. McClure’s Magazine in 1912 described Garros’s method of reaching high altitudes: “The process is simple—for Garros. He rose in spirals until his gasoline was gone, then glided down again in wide circles. It took him about an hour and a half to climb up and twelve minutes to come down.”

In 1913 Garros would be the first person to fly across the Mediterranean Sea.

But during World War I on October 8, 1918 Garros, flying for the French army, would be reported missing over German lines. On October 31 he would be reported killed in action at age twenty-nine.

But during World War I on October 8, 1918 Garros, flying for the French army, would be reported missing over German lines. On October 31 he would be reported killed in action at age twenty-nine.

Fort Worth’s driving park closed in the early 1920s. Today First Flight Park at 2700 Mercedes Avenue near the site of the driving park commemorates Garros’s achievement.

Fort Worth’s driving park closed in the early 1920s. Today First Flight Park at 2700 Mercedes Avenue near the site of the driving park commemorates Garros’s achievement.

(Aviation continued to be all the rage throughout 1911. In October pioneer aviator Cal Rodgers would land his Vin Fiz in a pasture that today we call “Ryan Place.”)

… My grandmother was born in a little village outside of Paris called Tours France, when I was little I remember she was always telling me they she saw airplanes flying over her farm before she saw her first car, and I was thinking that’s crazy there are cars and airplanes everywhere…

… And then came that Sunday afternoon in July, I was 10 years old, Grandma called long distance ( 80 miles ) and wanted to talk to me, she was so excited and crying “Did you see it WE landed on the moon”…

… And then I got it, in her lifetime she saw the turn of the century at 1, airplanes before she was 10, The year she turned 70 mankind left our planet, set foot on the moon, and everyone on earth could watch it on t.v., 14 seconds after it happened…

… And then she said something really crazy, by the time I was her age we would have little farming villages in glass greenhouses on the moon, and mankind will set foot on Mars…

… This February I will be 64 so we best get a move on…

Every generation sees so much change. I think those people born in the second half of the nineteenth century who lived long lives (80 or so) saw an especially amazing amount of change. For example, people born in 1860 who lived to be 80 experienced the Civil War, the coming of the railroad, automobile, airplane, indoor plumbing, penicillin, World War I and the start of World War II, telephone, radio, mechanical reproduction of sound, motion pictures, experimental television.

My generation, too, has witnessed great change, of course, the most monumental of which is no longer having to log on to America Online with a US Robotics 14.4K Sportster Faxmodem.

I have visited the First Flight park and admired the little replica of the plane. Garros was quite a war hero in France. They named the tennis park where the French Open is played after him. The French don’t refer to it as the French Open but call it the the Roland Garros.

Along the line of aviation. I keep hearing folks give reports about our hometown airline American. No one seems to remember we had another carrier…small as it may have been. Central. I was a stew for them and hate that they have disappeared from our history. Jane

Thanks for the tip, Jane. I am working up a post on Central Airlines.