When a big celebrity comes to town, often that town will present the celebrity with the key to the city. But when you’re that celebrity, and your name is “Harry Houdini,” who needs a key?

So, instead, when Houdini came to Fort Worth in January 1916 the city made him feel welcome by hanging him upside down in a straitjacket fifty feet off the ground in front of the Star-Telegram building in eighteen-degree weather.

Now that’s Texas hospitality, pardner! And that’s what happens when two master promoters—Harry Houdini and Amon Carter—have a playdate.

Houdini had come to town to appear at the Majestic vaudeville theater as part of his tour of the Interstate theater chain. Houdini might have been promoting Houdini, but Star-Telegram vice president and general manager Amon Carter would, as much as Amonly possible, use Houdini’s appearance to promote the Star-Telegram. Every day for a week Houdini’s face and feats were in the Star-Telegram to promote a public escape attempt that he would make—at the Star-Telegram building, of course.

Harry Houdini was billed as the “elusive American,” the “arch mystifier,” the “world-renowned self-liberator.” He had escaped from chains, ropes, handcuffs, shackles, safes, packing crates, plate-glass boxes, mail pouches, and straitjackets. He had leaped handcuffed into frozen rivers and had escaped from a Siberian prison van and from the jail cell that once held the assassin of President Garfield.

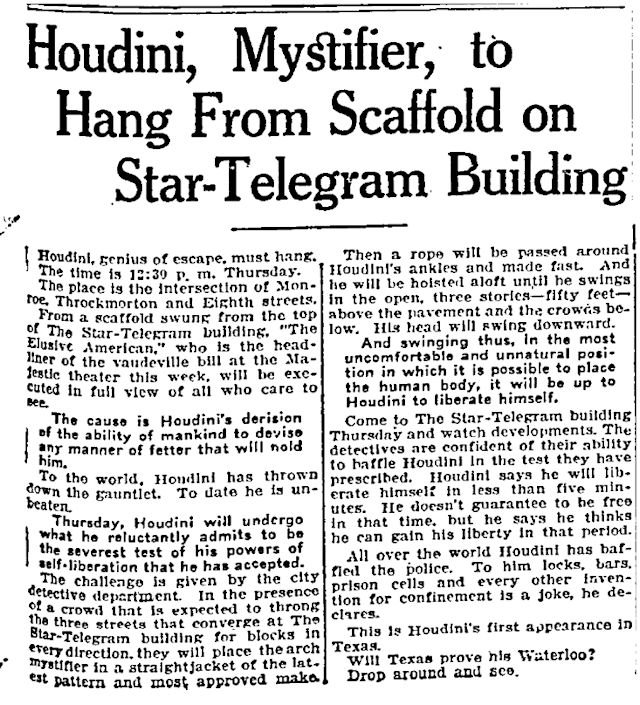

On January 11 the Star-Telegram announced that on January 13 city police detectives would wrap Houdini in a straitjacket, tie his ankles to a rope, and hoist him upside down to a scaffold suspended over the edge of the top of the Star-Telegram building. The Star-Telegram building in 1916 was located at 815 Throckmorton Street (the parking lot of the Waggoner Building today).

On January 11 the Star-Telegram announced that on January 13 city police detectives would wrap Houdini in a straitjacket, tie his ankles to a rope, and hoist him upside down to a scaffold suspended over the edge of the top of the Star-Telegram building. The Star-Telegram building in 1916 was located at 815 Throckmorton Street (the parking lot of the Waggoner Building today).

The Star-Telegram story of January 12 had the tone of a carnival barker: “It’s dollars to doughnuts you’ll be in front of The Star-Telegram office Thursday.” “The thrills will go chasing up and down your backbone like a million pollywogs in a pool along the West Fork.” “You have another engagement? Break it this minute.” “So you and you and you—come down in front of The Star-Telegram tomorrow at noon.” “So be there! The Star-Telegram!”

The Star-Telegram story of January 12 had the tone of a carnival barker: “It’s dollars to doughnuts you’ll be in front of The Star-Telegram office Thursday.” “The thrills will go chasing up and down your backbone like a million pollywogs in a pool along the West Fork.” “You have another engagement? Break it this minute.” “So you and you and you—come down in front of The Star-Telegram tomorrow at noon.” “So be there! The Star-Telegram!”

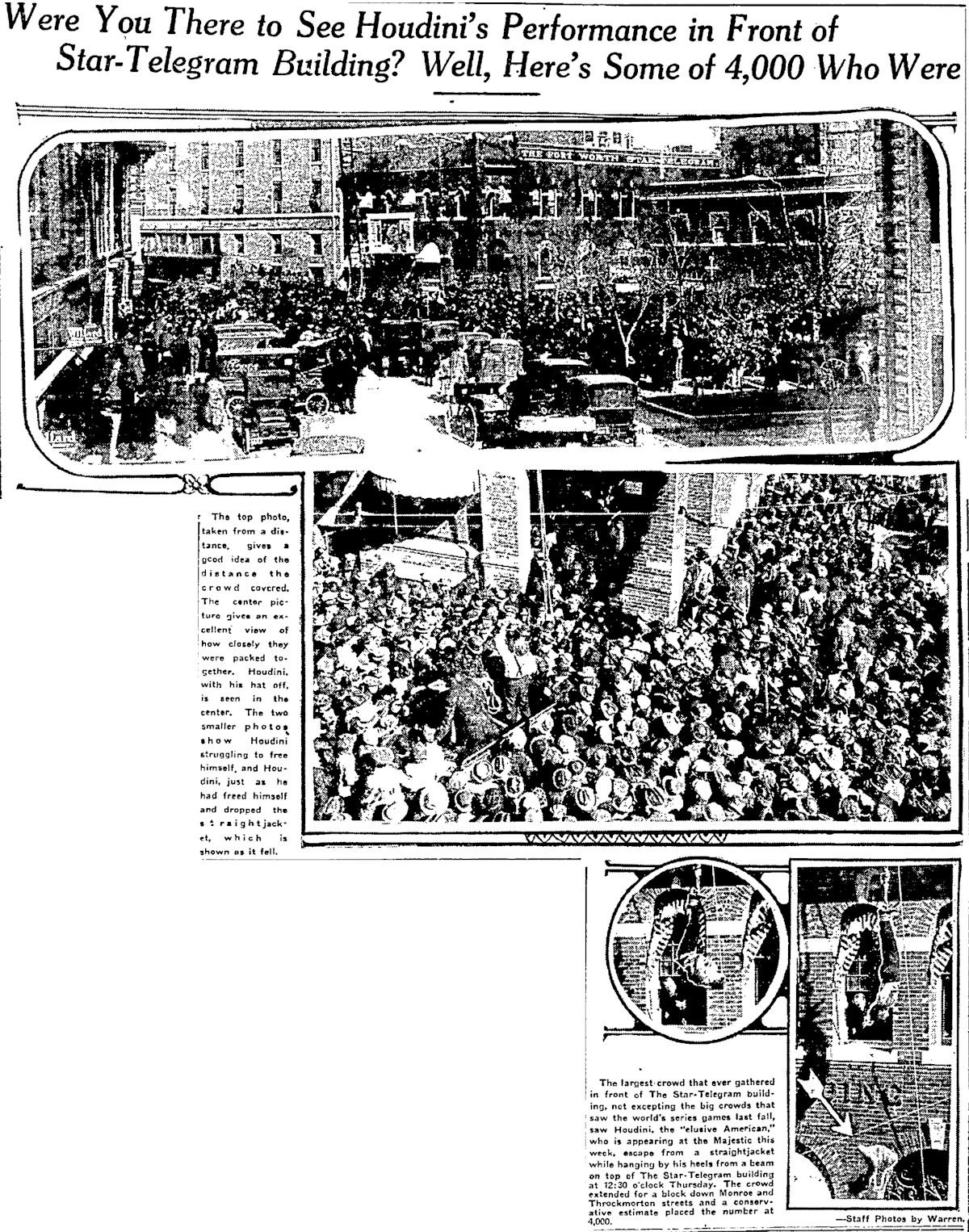

On January 13 the Star-Telegram reported that a crowd of four thousand—“the biggest ever seen in front of The Star-Telegram”—had watched Houdini shuck that straitjacket “in faster time than any man in the crowd dreamed he could.”

On January 13 the Star-Telegram reported that a crowd of four thousand—“the biggest ever seen in front of The Star-Telegram”—had watched Houdini shuck that straitjacket “in faster time than any man in the crowd dreamed he could.”

The next day the Star-Telegram printed photos of the escape, the words “Star-Telegram” appearing in both the headline and a photo.

The next day the Star-Telegram printed photos of the escape, the words “Star-Telegram” appearing in both the headline and a photo.

The Star-Telegram building. Adjacent was Ellison’s furniture store. (Photo from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

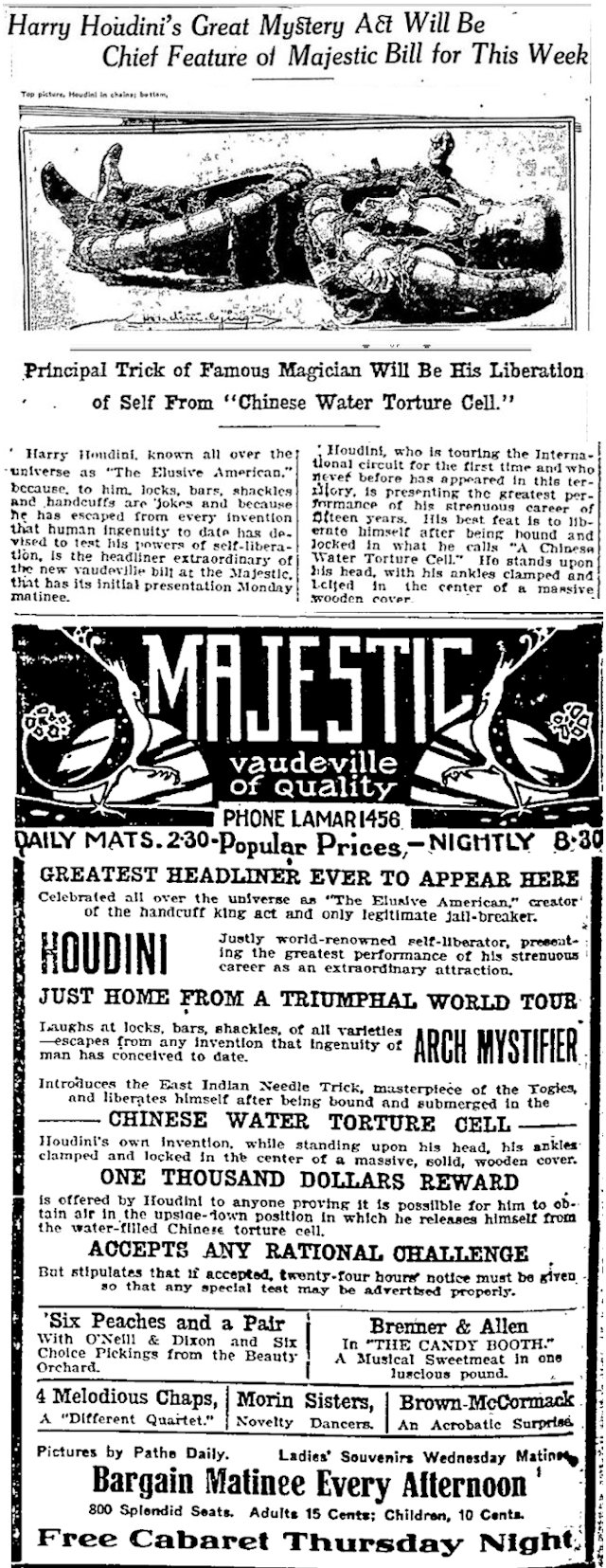

Meanwhile, on January 10 Houdini had begun a week-long engagement at the Majestic Theater performing his escape from the “Chinese water torture cell.” On January 9 the Majestic had begun its carpet-bomb ad campaign in the Star-Telegram.

Meanwhile, on January 10 Houdini had begun a week-long engagement at the Majestic Theater performing his escape from the “Chinese water torture cell.” On January 9 the Majestic had begun its carpet-bomb ad campaign in the Star-Telegram.

For Houdini’s nightly escape from the “Chinese water torture cell” on the Majestic stage, he had his ankles locked in a wooden clamp that was encased in steel. Then he was lowered upside down into the water-filled wooden “torture cell.” The cell was closed, bolted, and encased in a steel cage with twenty-two double padlocks. An attendant stood by with an ax in case Houdini needed to be rescued.

Fear not. The “escapist premier” freed himself in about ninety seconds.

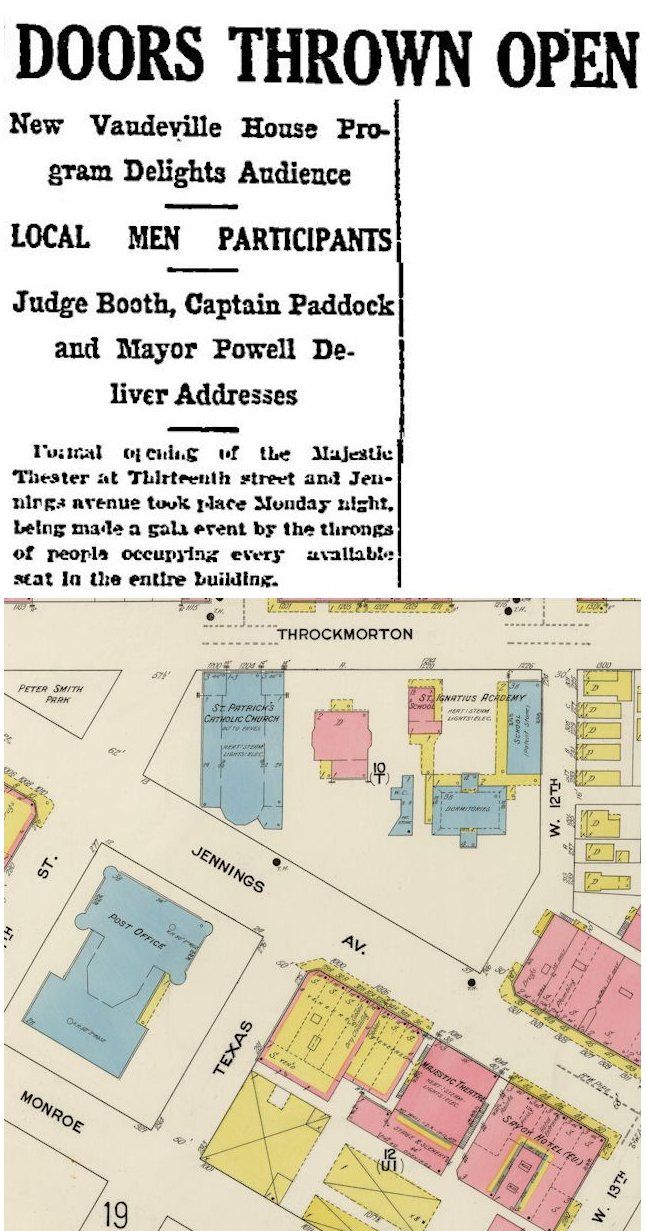

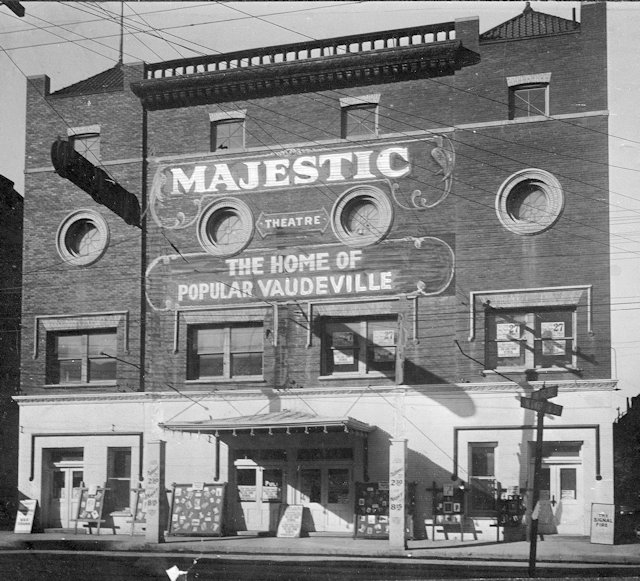

The Majestic Theater where Houdini performed in 1916 was not the original Majestic Theater. The Telegram on November 28, 1905 had announced the opening of the original Majestic Theater on Jennings Avenue south of the 1896 federal building/post office and west of St. Ignatius Academy. William J. Bailey built the theater. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

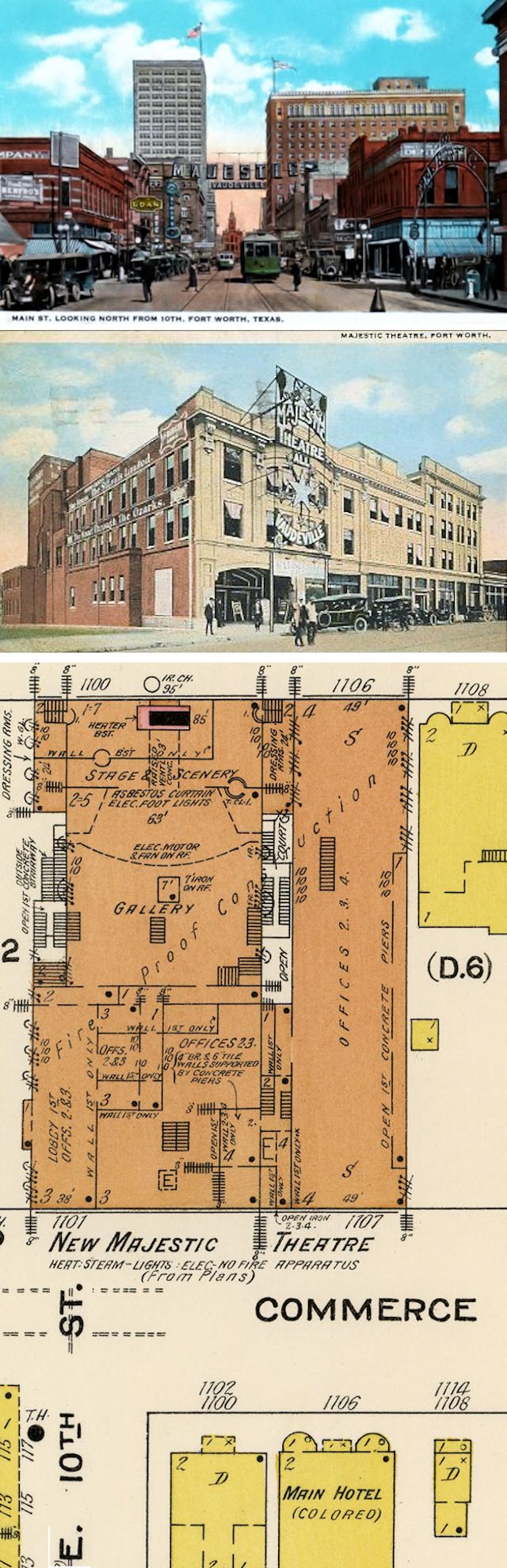

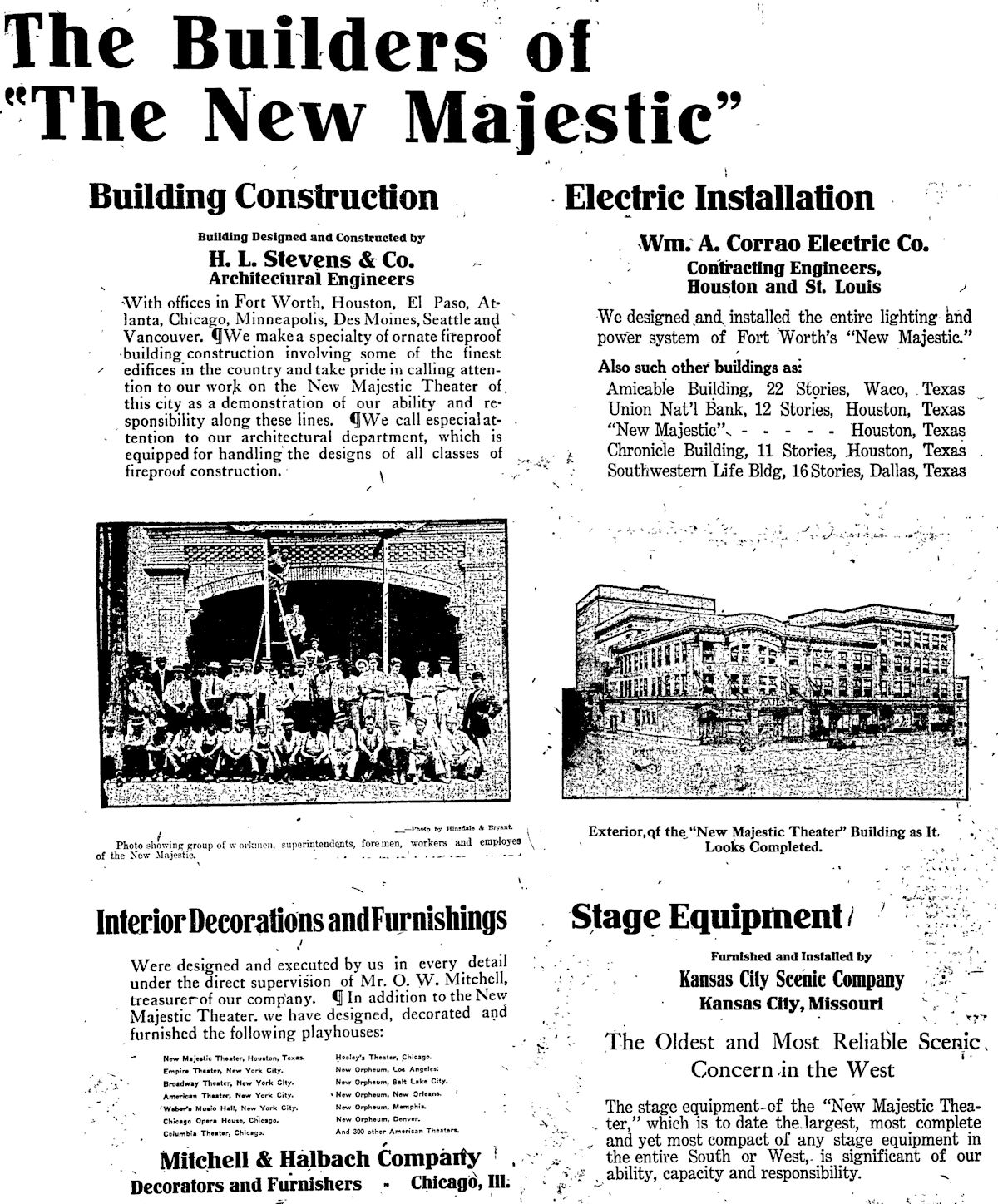

The second Majestic Theater was located on Commerce at 10th Street. And Harry Houdini could scarcely have chosen a nicer place to be tortured. Built in 1911 to present movies and vaudeville of the Interstate circuit, the Majestic Theater building did not present an impressive exterior. Ah, but plunk down your fifteen cents, buy a ticket, and step inside. The interior of the Majestic lived up to the theater’s name. Interstate mogul Karl Hoblitzelle had given Fort Worth opulence: statuary, gold leaf, marble columns, mosaic floors, crystal chandeliers, hand-painted curtain, smoking room, children’s nursery. By today’s standards, the Majestic interior looked more like an opera house than a vaudeville theater. A surviving example of Hoblitzelle’s opulent Interstate theaters is the Majestic Theater (1921) in Dallas. (In late 1911 the building that had housed the original Majestic Theater reopened as the Savoy Theater. In 1919 Bailey converted the building into a parking garage.)

The second Majestic Theater was located on Commerce at 10th Street. And Harry Houdini could scarcely have chosen a nicer place to be tortured. Built in 1911 to present movies and vaudeville of the Interstate circuit, the Majestic Theater building did not present an impressive exterior. Ah, but plunk down your fifteen cents, buy a ticket, and step inside. The interior of the Majestic lived up to the theater’s name. Interstate mogul Karl Hoblitzelle had given Fort Worth opulence: statuary, gold leaf, marble columns, mosaic floors, crystal chandeliers, hand-painted curtain, smoking room, children’s nursery. By today’s standards, the Majestic interior looked more like an opera house than a vaudeville theater. A surviving example of Hoblitzelle’s opulent Interstate theaters is the Majestic Theater (1921) in Dallas. (In late 1911 the building that had housed the original Majestic Theater reopened as the Savoy Theater. In 1919 Bailey converted the building into a parking garage.)

About the postcards: Although the second Majestic was located on Commerce, a “MAJESTIC” banner hung over Main Street. Rising in the background (left and right) are the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank and Texas Hotel (both 1921, Sanguinet and Staats).

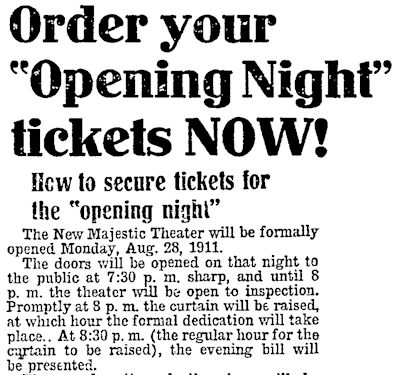

The second Majestic Theater opened on August 28, 1911. Clip is from the August 21 Star-Telegram.

The second Majestic Theater opened on August 28, 1911. Clip is from the August 21 Star-Telegram.

This ad appeared in the Star-Telegram on August 27, 1911.

This ad appeared in the Star-Telegram on August 27, 1911.

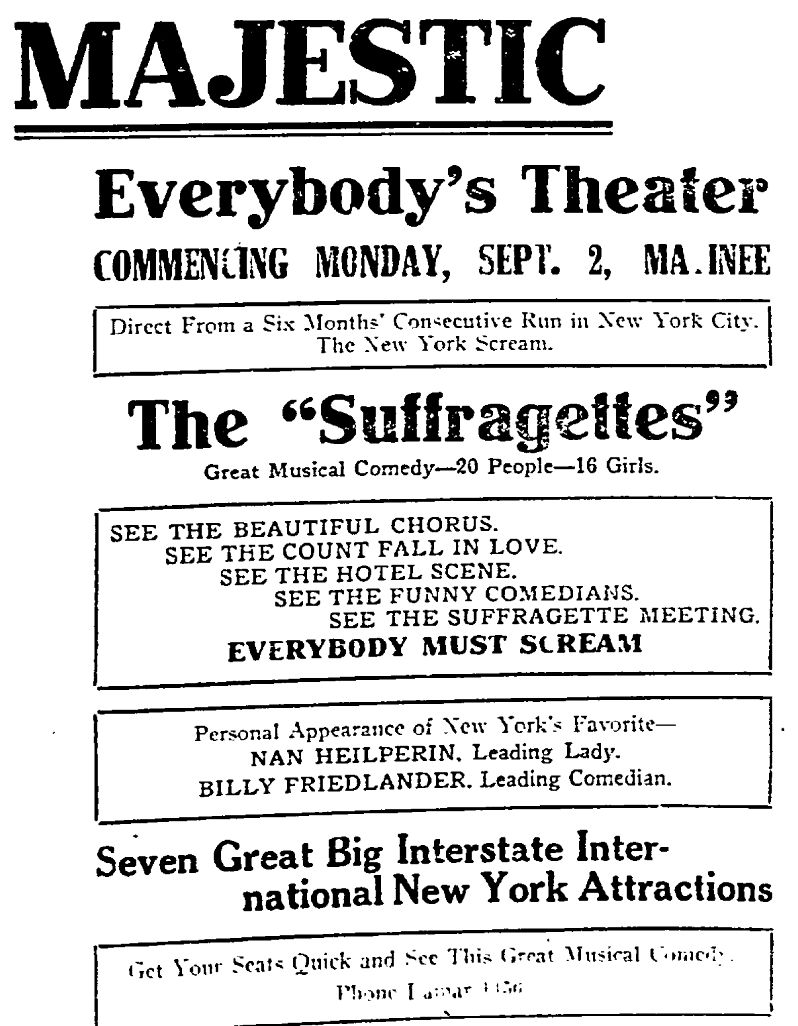

In 1912 the Majestic—“everybody’s theater”—presented the musical comedy Suffragettes. “Everybody must scream.” But not until 1920 would the Nineteenth Amendment give women the right to vote. Ad is from the September 1 Star-Telegram.

In 1912 the Majestic—“everybody’s theater”—presented the musical comedy Suffragettes. “Everybody must scream.” But not until 1920 would the Nineteenth Amendment give women the right to vote. Ad is from the September 1 Star-Telegram.

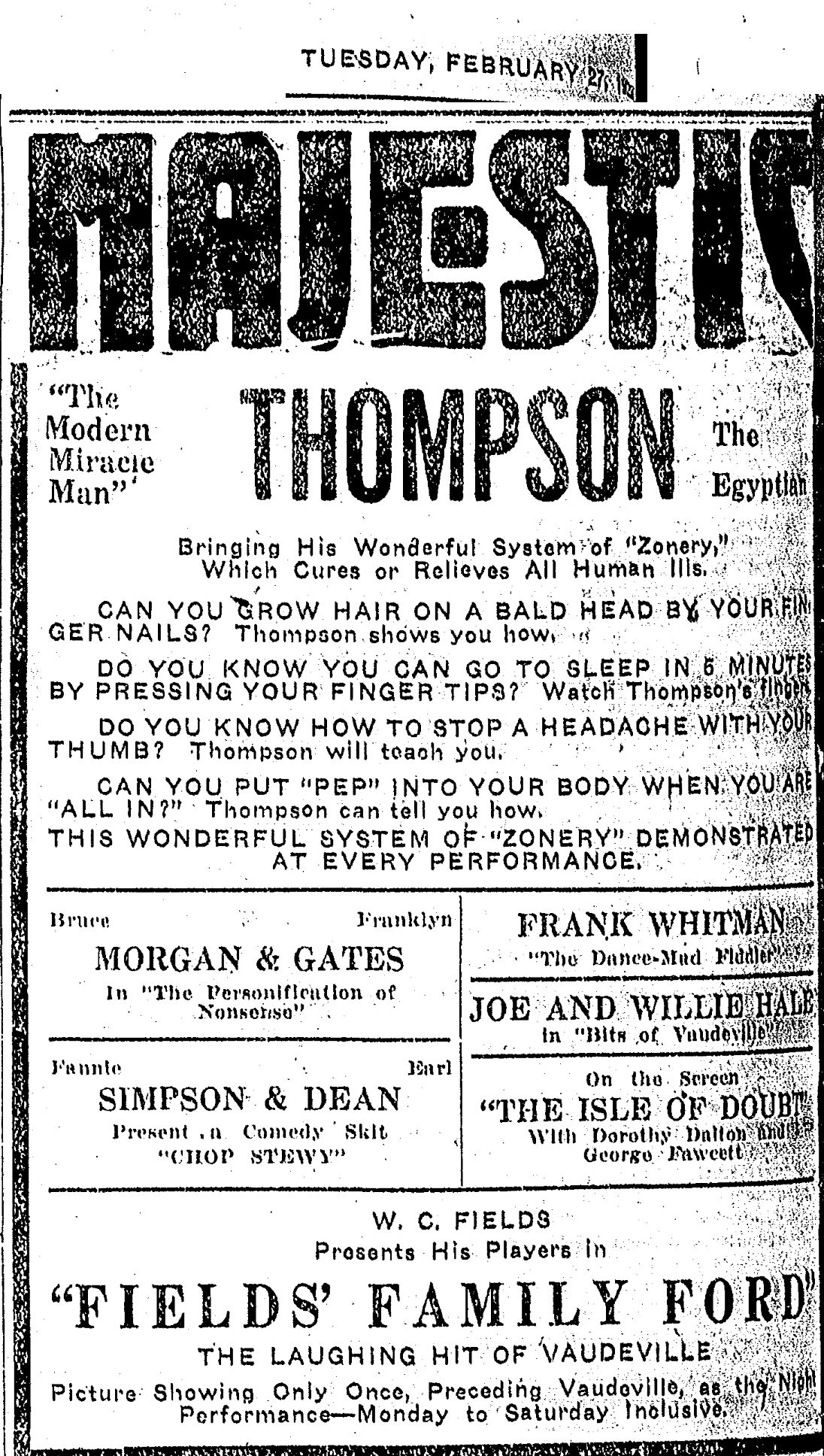

Ad is from the 1914 Star-Telegram.

Ad is from the 1914 Star-Telegram.

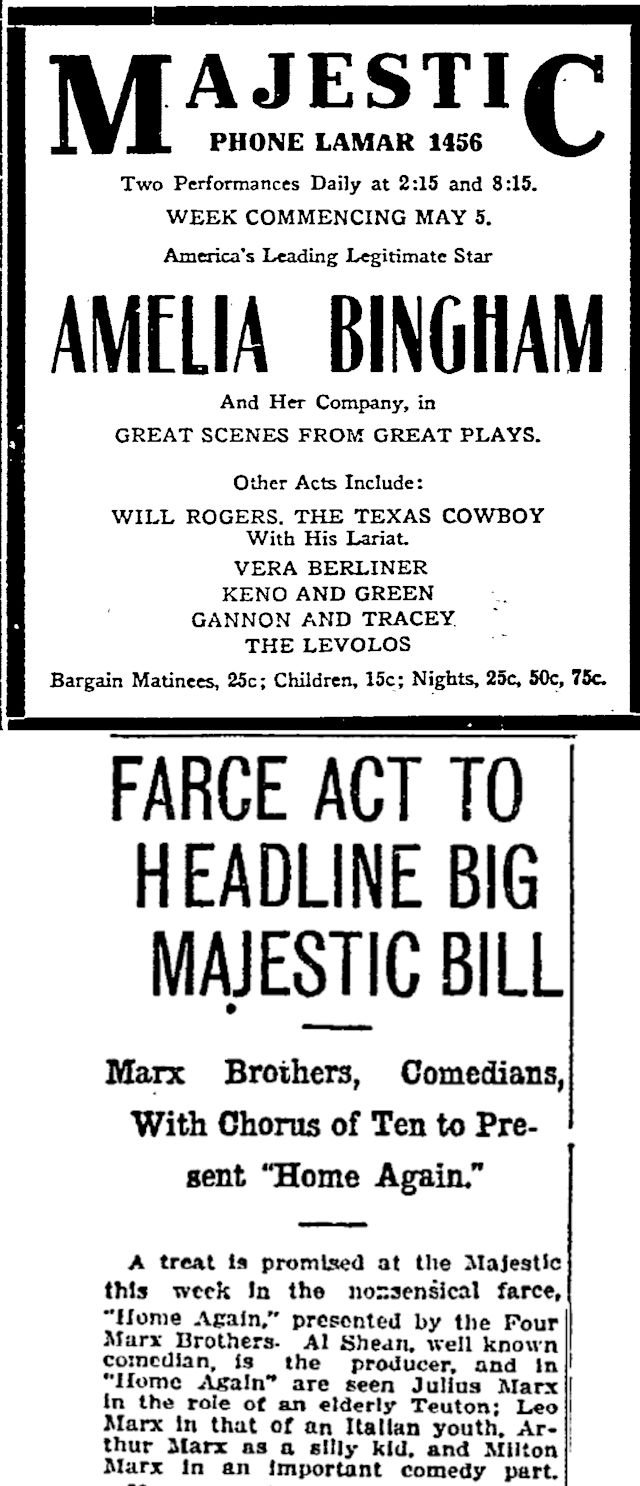

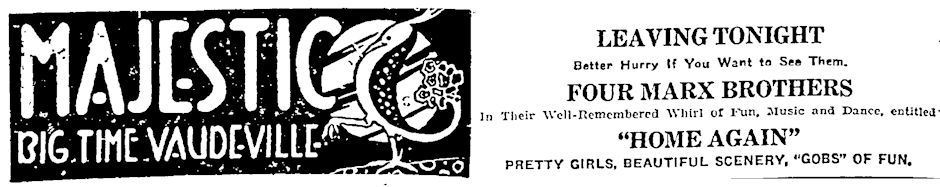

Among stars who appeared at the Majestic were Will Rogers, the Marx brothers, the Ritz brothers, Jack Benny, Fred Astaire, Burns and Allen, Mae West, Edgar Bergen, Katharine Hepburn, Eddie Cantor, Jimmie Rodgers, and Bert Lahr, Jack Haley, and Ray Bolger, who in 1939 would be the Cowardly Lion, Tin Man, and Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz. Others to appear on the Majestic stage included Enrico Caruso, Rose Marie (Dick Van Dyke Show), local girl Ginger Rogers, and Irene Castle, widow of Vernon Castle. In the bottom clip from 1914, Julius is Groucho, Leo is Chico, Arthur is Harpo, and Milton is Gummo.

Among stars who appeared at the Majestic were Will Rogers, the Marx brothers, the Ritz brothers, Jack Benny, Fred Astaire, Burns and Allen, Mae West, Edgar Bergen, Katharine Hepburn, Eddie Cantor, Jimmie Rodgers, and Bert Lahr, Jack Haley, and Ray Bolger, who in 1939 would be the Cowardly Lion, Tin Man, and Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz. Others to appear on the Majestic stage included Enrico Caruso, Rose Marie (Dick Van Dyke Show), local girl Ginger Rogers, and Irene Castle, widow of Vernon Castle. In the bottom clip from 1914, Julius is Groucho, Leo is Chico, Arthur is Harpo, and Milton is Gummo.

Ad is from the 1917 Star-Telegram.

Mae West was twenty-one years old and nineteen years away from She Done Him Wrong when she appeared at the Majestic in 1914.

Mae West was twenty-one years old and nineteen years away from She Done Him Wrong when she appeared at the Majestic in 1914.

In 1927, when William Claude Dukenfield appeared on the Majestic stage in Fields’ Family Ford, “the laughing hit of vaudeville,” he was forty-seven years old and thirteen years away from co-scripting My Little Chickadee with co-star Mae West. W. C. Fields appeared at the Majestic on the same bill with “Thompson the Egyptian,” who could, through the magic of “zonery,” show his audience how to grow hair on a bald head and relieve “all human ills.”

In 1927, when William Claude Dukenfield appeared on the Majestic stage in Fields’ Family Ford, “the laughing hit of vaudeville,” he was forty-seven years old and thirteen years away from co-scripting My Little Chickadee with co-star Mae West. W. C. Fields appeared at the Majestic on the same bill with “Thompson the Egyptian,” who could, through the magic of “zonery,” show his audience how to grow hair on a bald head and relieve “all human ills.”

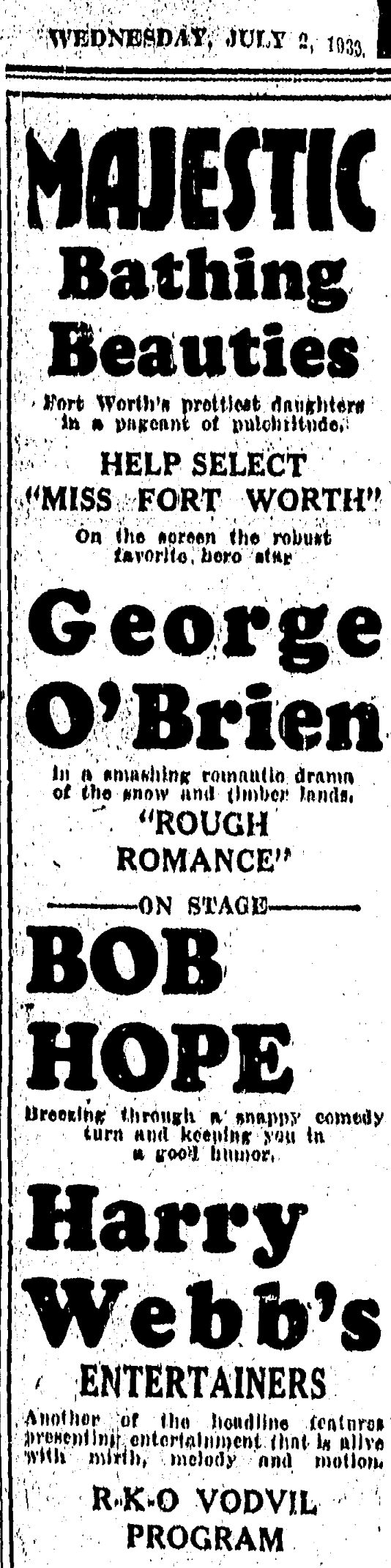

Bob Hope was twenty-seven years old in 1930 and eight years away from his first film appearance in The Big Broadcast of 1938, in which he sang “Thanks for the Memory.” He appeared on the Majestic stage with “Fort Worth’s prettiest daughters in a pageant of pulchritude.”

Bob Hope was twenty-seven years old in 1930 and eight years away from his first film appearance in The Big Broadcast of 1938, in which he sang “Thanks for the Memory.” He appeared on the Majestic stage with “Fort Worth’s prettiest daughters in a pageant of pulchritude.”

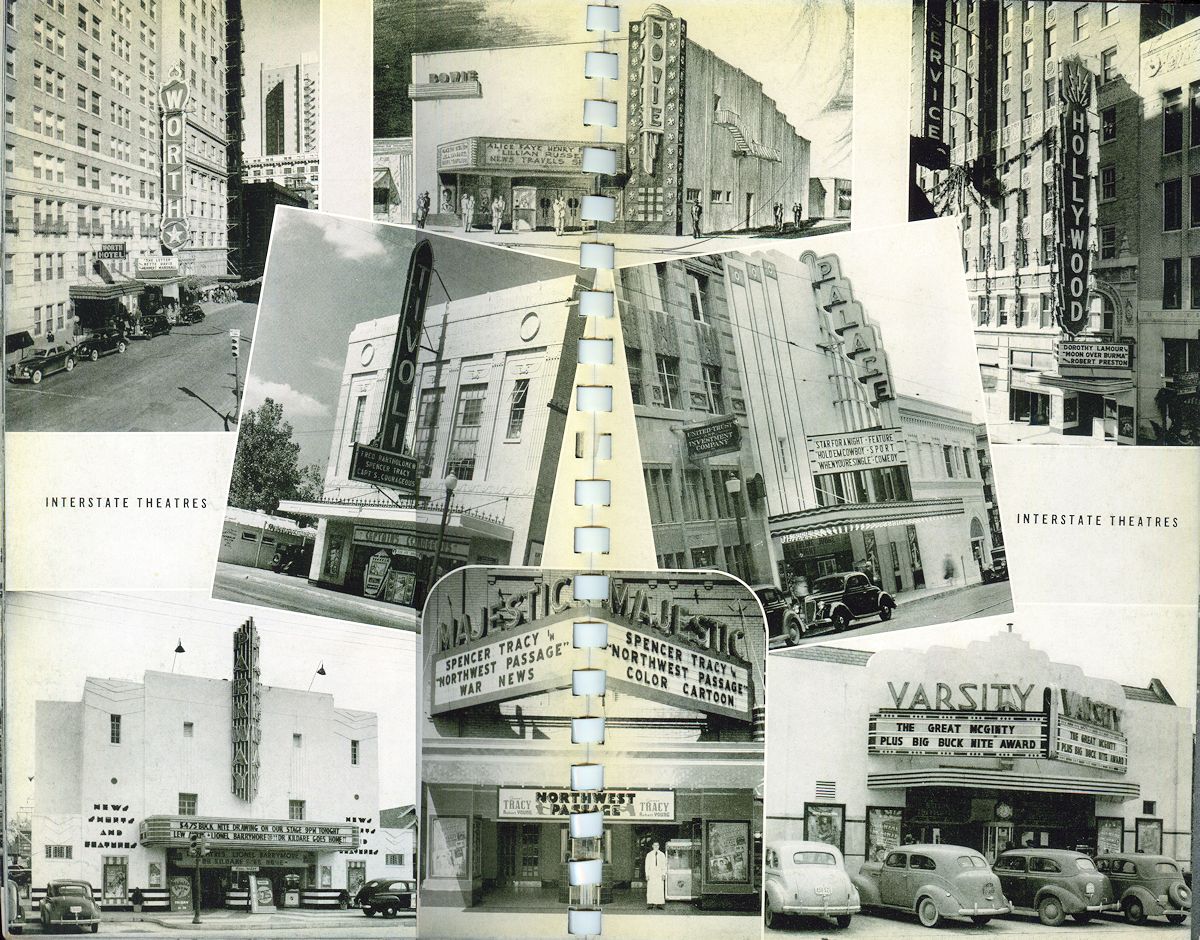

The Interstate chain would eventually operate a dozen theaters in Fort Worth, including the Majestic, Hollywood, Worth, Palace, Bowie, Tivoli, Varsity, and Parkway. (W. D. Smith photo in Fort Worth in Pictures.)

The Interstate chain would eventually operate a dozen theaters in Fort Worth, including the Majestic, Hollywood, Worth, Palace, Bowie, Tivoli, Varsity, and Parkway. (W. D. Smith photo in Fort Worth in Pictures.)

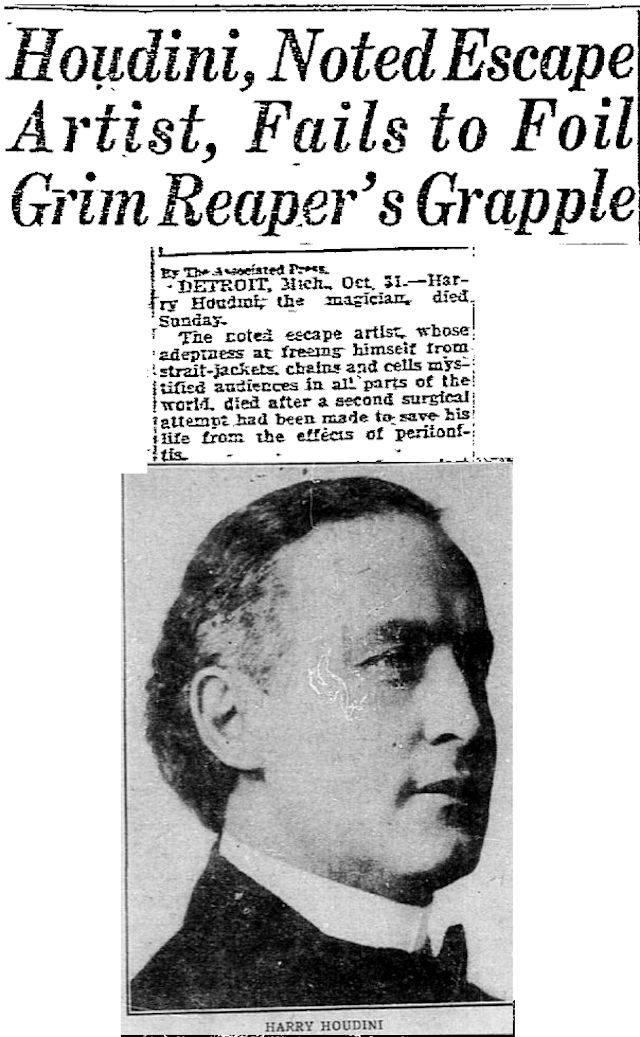

As for Harry Houdini, he could escape from everything but Amon Carter and death. Clip is from the November 1, 1926 Dallas Morning News.

As for Harry Houdini, he could escape from everything but Amon Carter and death. Clip is from the November 1, 1926 Dallas Morning News.

And the Majestic Theater could escape from everything but change. The theater closed in 1964, and in the summer of 1966 the building was demolished when fourteen blocks of the south end of downtown (the old Hell’s Half Acre) were razed to build the $16 million ($113 million today) Tarrant County Convention Center.

The Majestic Theater in 1955. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The Majestic Theater in 1955. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

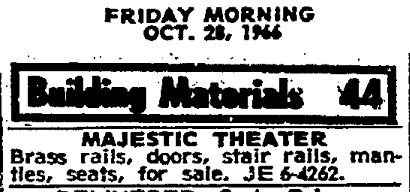

By October 1966 the mortal remains of the once-majestic Majestic had been reduced to an ad in the “Building Materials” classification.

By October 1966 the mortal remains of the once-majestic Majestic had been reduced to an ad in the “Building Materials” classification.

Do you have any information about “Bank Night” that was held at the Majestic Theater in Fort Worth. My mother won a Bank Night drawing some time in the 1930-40 period. Would like to know about it.

Thad, bank night was a lottery game held by theaters during the Depression. It began as a franchise by an ex-20th Century Fox employee and had 5,000 theaters participating but also had imitators. People registered their name with a theater. On bank night one of those names was drawn at random. Because the person whose name was drawn had a limited time to claim the prize, it was beneficial to be in the theater on bank night. Players were not REQUIRED to buy a ticket to the theater, but many did anyway. To say nothing of concessions. In 1937 bank night was controversial around the country because some people interpreted it as gambling, which was illegal. There were many court cases. The Star-Telegram in an editorial in 1937 declared bank night indeed to be a lottery, which was gambling, which was illegal. That year the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that bank nights are lotteries.

Oddly, the only Fort Worth theater I find hosting a bank night was the New Liberty in 1934. The prize was a $125 ($2,400 today) bank account.

Wow, the Chief Bailey mentioned who questioned if Houdini could escape from the straight jacket was my half great-uncle Cullen Bailey!! He was chief of Police at that time!

It is a shame the old theaters were not preserved. This link (from UNT’s Texas history portal) is to a WBAP-TV clip of Elvis fans lined up outside the Worth to see “Love Me Tender” in 1956: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc938275/m1/#track/1

Excellent clip! I will work that in. Thanks.

Excellent piece! Love the maps! Do you have any info or referrals on Houdini’s appearances in San Antonio?

Thanks, David. I did not search the Fort Worth papers for other Texas appearances by Houdini. Could find no clips on his Fort Worth motorcycle stunt with local boy Ormer Locklear in 1916 or his program at the local Ku Klux Klan in 1924. The Houdini File

BTW, during this same 1916 engagement, Houdini was dragged down Main Street tied up behind a motorcycle. I’ve never see a photo or newspaper clipping of that stunt. Maybe one to research someday?

John, I had read that and searched the local archives for some mention but found none-which proves nothing-but did mention it in a post on Ormer Locklear.

Wonderful post! Thank you. I will share this link on my own Houdini blog.

Thanks, John. Wish I could have seen that spectacle. Wild About Harry

It did whisper, Mike. A few days before it was demolished, I had a date with a boy whose father owned the company doing the tear-down. We had dinner at Cross Keys and then we toured the Majestic- in the dark, with flashlights. No ghosts- I was mostly afraid of falling through a floor.

What a great memory for you. I have no memory of even being aware of the Majestic while it stood. But I was majoring in Oblivious. Shame that not one of those grand theaters survived. Dallas saved its Majestic.

Oh for a time machine to attend such vaudeville! This site is the next best thing. We’d love to see 20 people and 16 girls and thereby SCREAM.

Thanks, Sally and Ike. How I wish we had preserved that grand building. Late at night, when there’s no one around to heed the “walk/don’t walk” signals downtown, the old theater would probably still be whispering “vo dee oh doh” and “yowsah yowsah yowsah.”