On May 2, 1922—a century ago today—radio station WBAP officially began broadcasting.

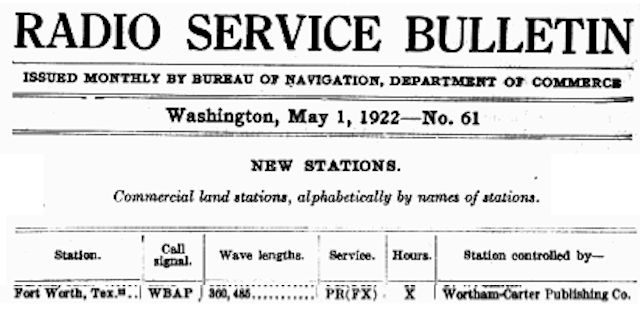

The new station had appeared in the May 1 edition of the Department of Commerce’s Radio Service Bulletin. (“Wortham” was Louis J. Wortham, a founder and editor of the Star-Telegram and a state legislator from Tarrant County.)

The new station had appeared in the May 1 edition of the Department of Commerce’s Radio Service Bulletin. (“Wortham” was Louis J. Wortham, a founder and editor of the Star-Telegram and a state legislator from Tarrant County.)

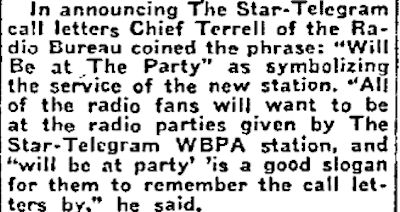

The Star-Telegram received its federal license to operate its “radio plant” on May 3. According to WBAP’s website, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover named the station and said the call letters stand for “We Bring A Program.” But this clip from May 3 says that Radio Bureau chief William D. Terrell said the call letters stand for “Will Be At Party.”

Either way, this announcement is buried on page 19 of a twenty-page newspaper, perhaps reflecting the doubts of Star-Telegram vice president and general manager Amon Carter about the future of the new technology. What if radio was just a fad, like flappers or the foxtrot? Or, worse, what if radio was not a fad? What if it became popular and killed newspapers, as some predicted? So, Carter had hedged his bets. He had told circulation manager Harold (“Hired Hand”) Hough that Hough could spend “up to $300” ($4,300 today) to get a radio station on the air. Carter had warned Hough: “When that $300 is gone, we’re out of the radio business.”

That was one hundred years ago.

The people who got WBAP radio onto the air in 1922 were pioneers, just as the people (including Hough again) who would get WBAP TV onto the air in 1948 were pioneers. They were making it up as they went along. Suddenly circulation manager Harold Hough found himself learning radio on the fly: He became program director, chief engineer, chief announcer. And chief cowbell clanger: Early on the station adopted the sound of a cowbell as its audible logo.

The station started with ten watts of power, which carried marginally farther than a shout. But technology advanced rapidly that year. By the end of the year the station would have three hundred watts, on its way by 1928 to the fifty thousand watts that make it one of the most powerful stations in the United States.

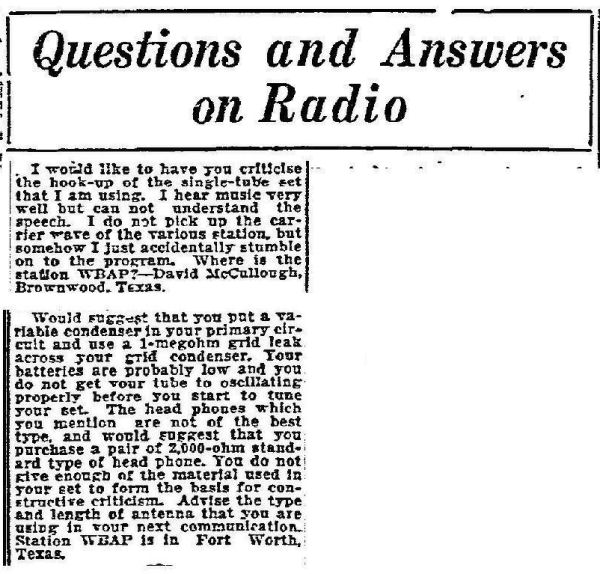

This 1922 clip from the Dallas Morning News offers advice to those readers building their own radio receivers. Imagine a time when someone in Brownwood did not know where WBAP is located.

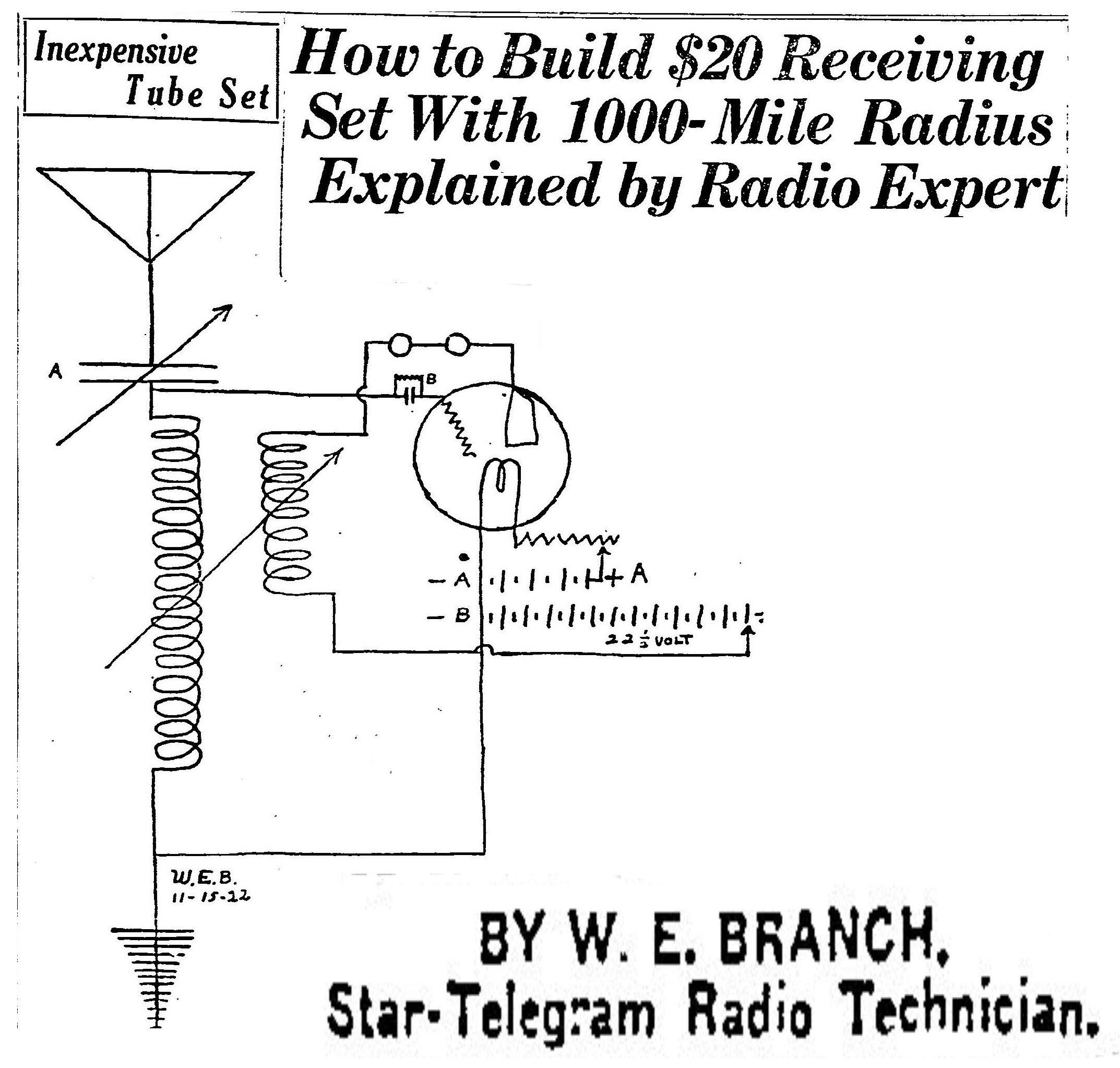

Another WBAP radio pioneer was William Ellison Branch (pictured), who would create radio station KFJZ and later operate it from his house in Poly. Branch was WBAP’s first radio technician. He also wrote a Star-Telegram column about the newfangled technology. Radio was fairly new in 1922, and each day brought new reports about advances in the invisible marvel. But predictions about the future of radio were wildly divergent, with some saying radio is just a fad that will fizzle and others saying radio is here to stay and will replace the telephone.

Another WBAP radio pioneer was William Ellison Branch (pictured), who would create radio station KFJZ and later operate it from his house in Poly. Branch was WBAP’s first radio technician. He also wrote a Star-Telegram column about the newfangled technology. Radio was fairly new in 1922, and each day brought new reports about advances in the invisible marvel. But predictions about the future of radio were wildly divergent, with some saying radio is just a fad that will fizzle and others saying radio is here to stay and will replace the telephone.

WBAP may have begun tentatively, but it soon was Amon Carter’s pet project. By the end of the month the station was offering to help a couple be married by radio—while flying in an airplane. Within weeks WBAP was broadcasting church services and broadcasting to a passenger train. It also broadcast a Fort Worth Panthers baseball game.

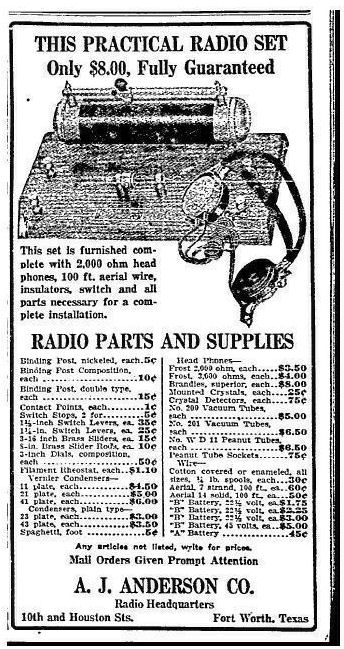

Soon longtime sporting goods and gun store owner A. J. Anderson, who in 1884 had helped Jim Courtright escape, was getting in on the craze.

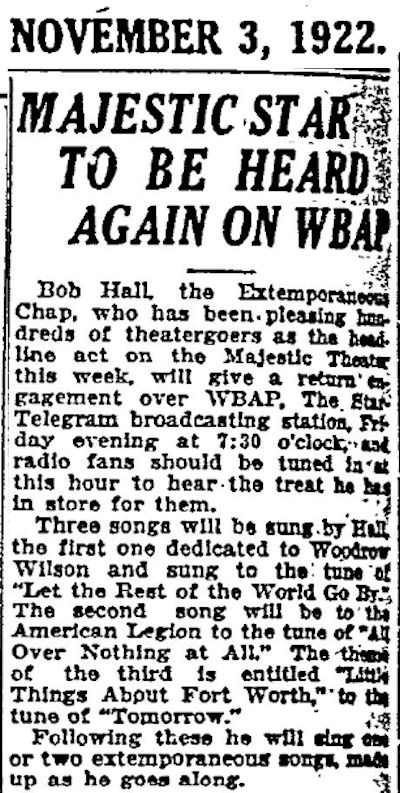

Performers who appeared at local vaudeville theaters also appeared on WBAP. In November 1922 Bob Hall, the Extemporaneous Chap, took time from the stage at the Majestic Theater to perform on WBAP.

Performers who appeared at local vaudeville theaters also appeared on WBAP. In November 1922 Bob Hall, the Extemporaneous Chap, took time from the stage at the Majestic Theater to perform on WBAP.

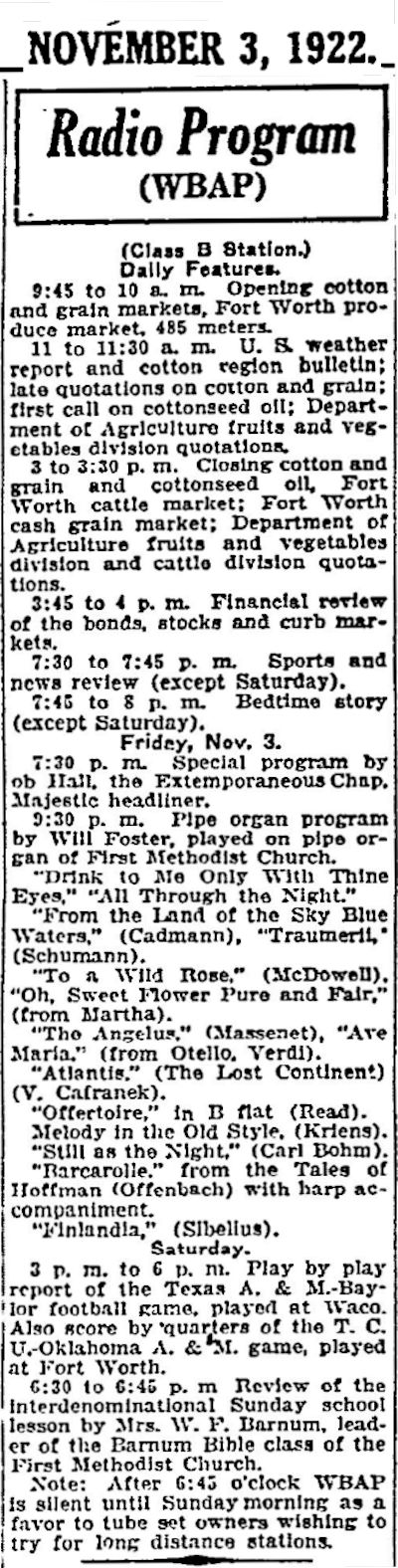

By November—after just seven months on the air—this was the WBAP broadcast schedule. The station presented a mix of financial, agricultural, sports, and news reports, music performed by local musicians, even a bedtime story at 7:45 p.m. Note that the station would broadcast a play-by-play report of the A&M-Baylor football game and that the station would go “silent” from 6:45 p.m. Saturday night until Sunday morning so that “tube set owners” could have a little elbow room to try to tune in long-distance stations.

By November—after just seven months on the air—this was the WBAP broadcast schedule. The station presented a mix of financial, agricultural, sports, and news reports, music performed by local musicians, even a bedtime story at 7:45 p.m. Note that the station would broadcast a play-by-play report of the A&M-Baylor football game and that the station would go “silent” from 6:45 p.m. Saturday night until Sunday morning so that “tube set owners” could have a little elbow room to try to tune in long-distance stations.

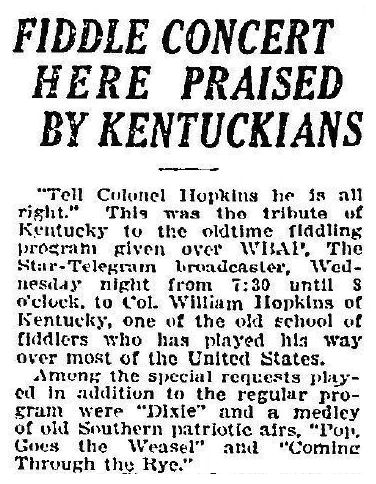

Amon Carter’s newspaper was the perfect PR agent for Amon Carter’s radio station. Each day the newspaper printed several news stories about the station. In the beginning Carter and the Star-Telegram were especially keen on telling readers how far away WBAP, “the Star-Telegram broadcaster,” was being received on the newfangled technology. Each day the newspaper printed a report about listeners enjoying WBAP in this city or that state. This clip, also from November 1922, shows that the station was reaching Kentucky. Colonel Hopkins’s fiddle concert included “Pop Goes the Weasel,” “Coming Through the Rye,” and “Dixie.”

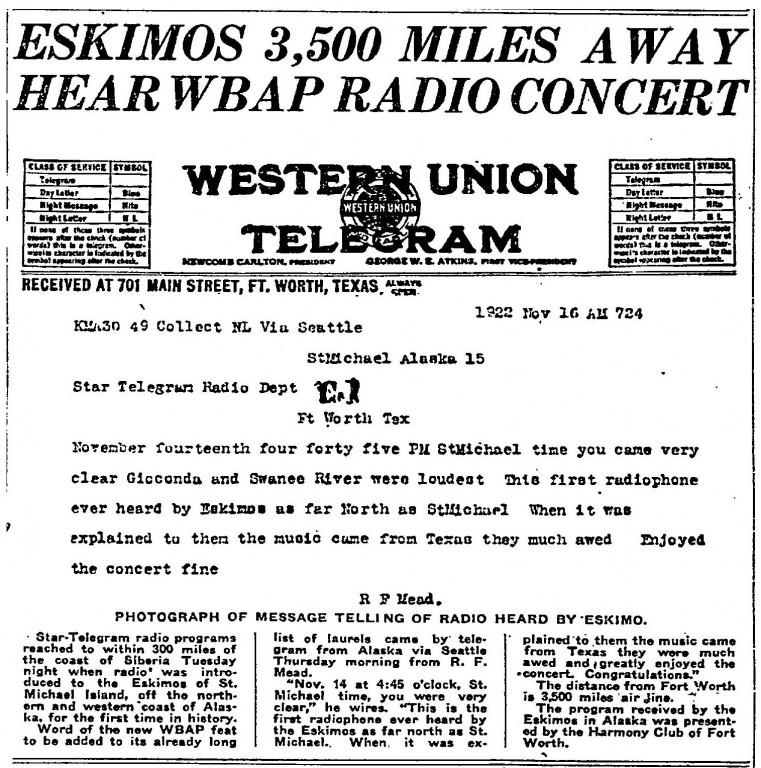

But soon WBAP topped that: A few days later the Star-Telegram boasted that WBAP had been heard by Eskimos 3,500 miles away at St. Michael, Alaska. Imagine Eskimos listening to, for example, that WBAP fiddle concert by Colonel Hopkins and looking at each other in puzzlement:

“What’s a weasel?”

“What’s rye?”

“Who’s Dixie?”

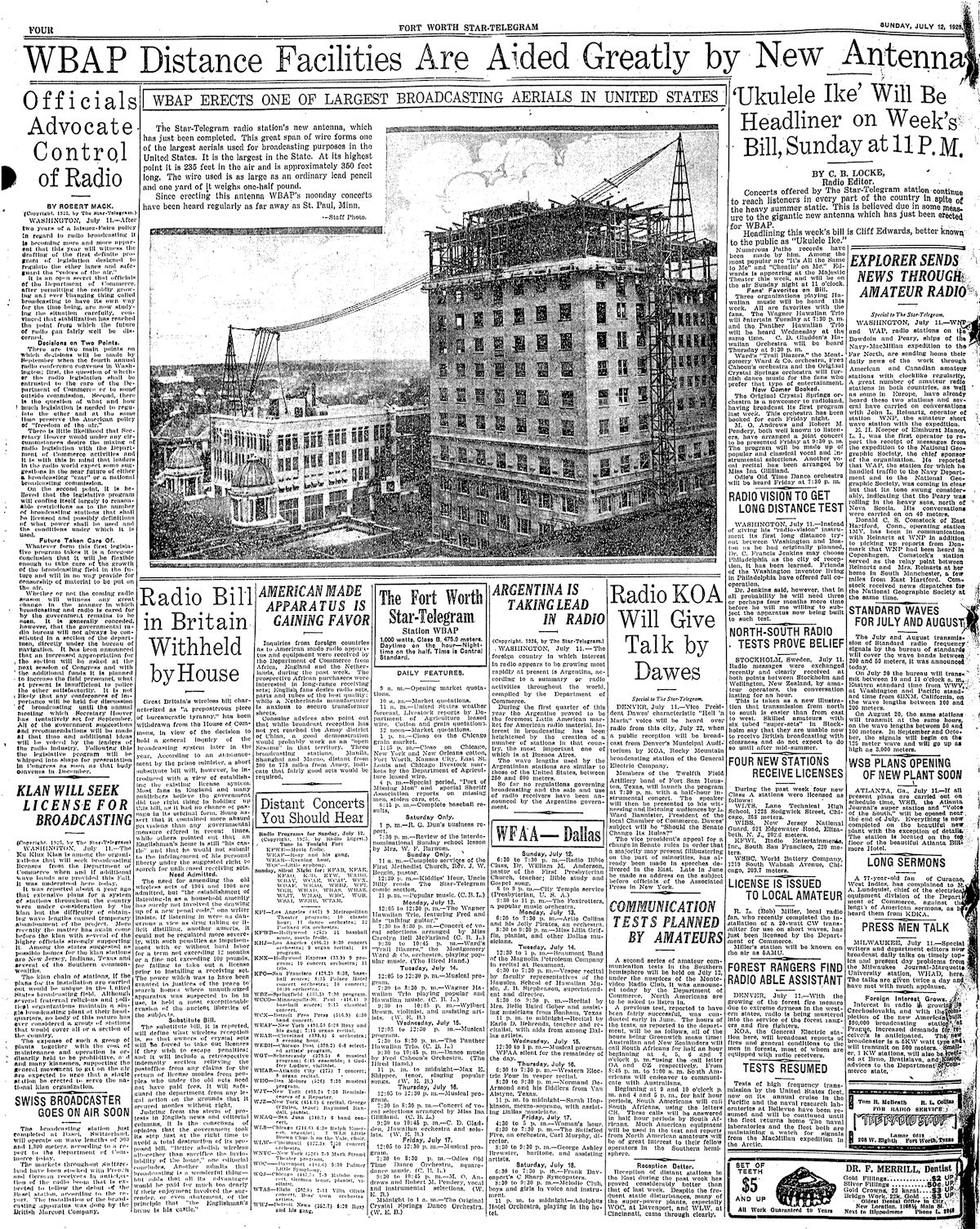

In 1925 WBAP really went the distance: To reach even farther, a huge antenna was hung like a clothesline from the top of the Star-Telegram building to the top of the unfinished Fort Worth Club Building. By 1925 the newspaper was devoting an entire page to the world of radio. The two domes in the lower left were atop First Methodist Church (1908). (Notice in the left column that the Ku Klux Klan had applied for a license to broadcast.)

In 1925 WBAP really went the distance: To reach even farther, a huge antenna was hung like a clothesline from the top of the Star-Telegram building to the top of the unfinished Fort Worth Club Building. By 1925 the newspaper was devoting an entire page to the world of radio. The two domes in the lower left were atop First Methodist Church (1908). (Notice in the left column that the Ku Klux Klan had applied for a license to broadcast.)

After its remarkable first year in 1922 WBAP, of course, would go on to have a long career as a country music powerhouse, and its trademark cowbell would clang on with deejay Bill Mack. WBAP is now news/talk format.