“We took no heed of his dying prayer.

In a narrow grave we buried him there.

In a narrow grave just six by three

We buried him there on the lone prairie”

The “him” of “The Dying Cowboy” ballad could apply to three males in this story of early Fort Worth—males of three generations of a family who were buried nineteen years apart “there on the lone prairie,” each of the three males earning a “first” in Fort Worth history.

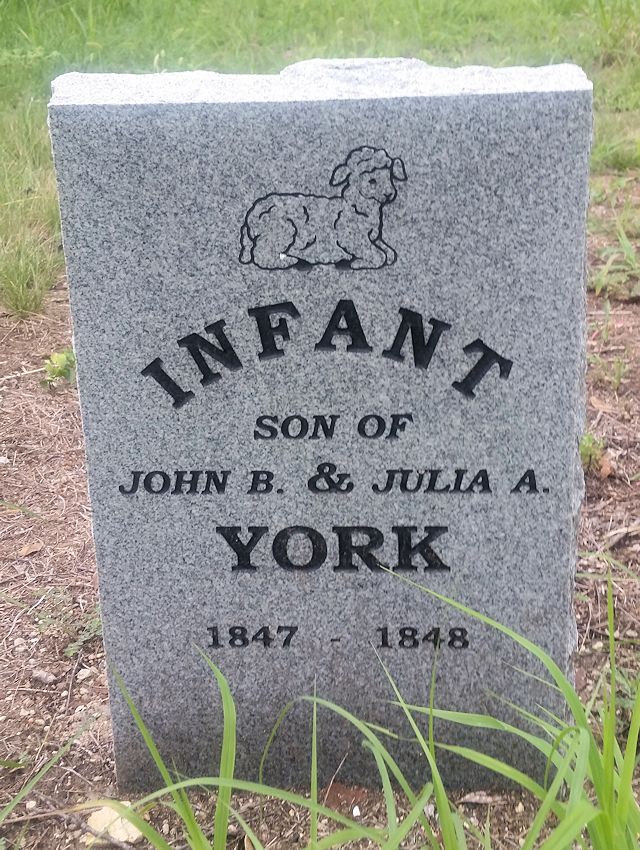

But for one of these three males, “a narrow grave just six by three” feet would have been far more spacious than necessary. And his “first” was a sad distinction: A boy was only eighteen months old when he died in 1848 and was the first person buried in the little cemetery started for his and related families.

That cemetery is one of several in Fort Worth that you don’t just stumble across.

Just northeast of the stockyards and south of Northeast 28th Street, freight trains rumble past each other, metal on metal screeching, on two tracks. A strip of no-man’s-land 150 feet wide separates the two tracks. In that narrow strip, in an oasis of trees between an aluminum foundry and an auto salvage yard, lies little Mitchell Cemetery.

Under one of those trees lies the unmarked grave of the infant York.

Also buried in Mitchell Cemetery, in another unmarked grave, is John B. York, father of the baby boy. More later on John B. York and his first in local history.

Only two original tombstones in little Mitchell Cemetery have survived time, vandalism, and encroachment by railroads. This tombstone is incomplete. The hand engraving includes the word Anderson and may refer to Mrs. E. O. Anderson, who was buried in the cemetery in 1867.

Only two original tombstones in little Mitchell Cemetery have survived time, vandalism, and encroachment by railroads. This tombstone is incomplete. The hand engraving includes the word Anderson and may refer to Mrs. E. O. Anderson, who was buried in the cemetery in 1867.

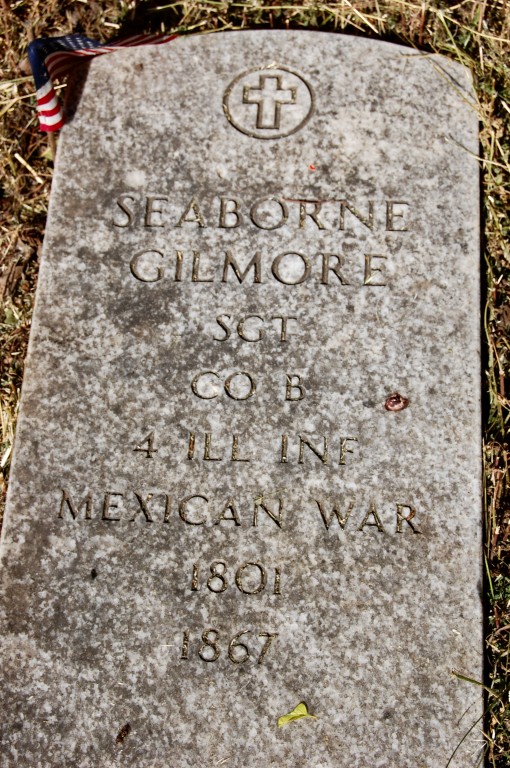

The only complete original tombstone is that of Seaborne Gilmore, who was grandfather of the infant York and father-in-law of John B. York. York’s wife, Julia, was Seaborne Gilmore’s daughter.

In 1848, when the York and Gilmore families settled three miles north of the Trinity River and began homesteading, there was no Fort Worth—military or municipal. There was only prairie. And the prairie came in just one flavor: lone.

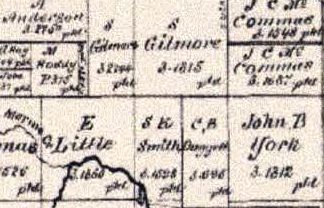

This detail of an 1895 county map shows the York and Gilmore surveys east and northeast of the confluence of Marine Creek and the Trinity River. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

This detail of an 1895 county map shows the York and Gilmore surveys east and northeast of the confluence of Marine Creek and the Trinity River. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

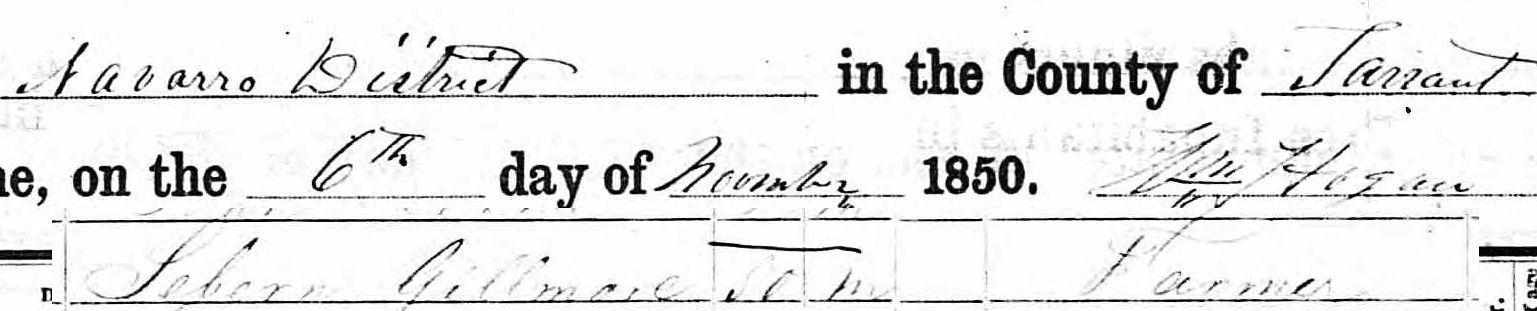

In 1850 came the “first” of the York infant’s grandfather: Seaborne Gilmore was elected Tarrant County’s first county judge. Gilmore was listed as a farmer, age fifty, in still another first: Tarrant County’s first census in 1850.

In 1850 came the “first” of the York infant’s grandfather: Seaborne Gilmore was elected Tarrant County’s first county judge. Gilmore was listed as a farmer, age fifty, in still another first: Tarrant County’s first census in 1850.

According to another daughter of Seaborne Gilmore, Martha Gilmore Mitchell, Judge Gilmore presided over the 1856 election in which Fort Worth took the county seatdom from Birdville. The election was hotly contested, sometimes with shots of whiskey, sometimes with shots of lead.

“While my father counted the votes he could hear the reports of pistols on the outside,” Martha Mitchell later told the Star-Telegram. (In 1923 Martha Mitchell, who was born in 1849, claimed to have been the first white child born in Fort Worth.)

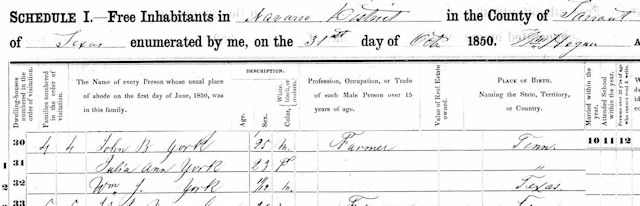

The 1850 census showed John B. and Julia York to have another son, William, who was eleven months old. John, a farmer, was twenty-five. Julia was twenty-three.

The 1850 census showed John B. and Julia York to have another son, William, who was eleven months old. John, a farmer, was twenty-five. Julia was twenty-three.

In 1852 John B. York was elected Tarrant County’s second sheriff. York had previously been a deputy under Tarrant County’s first sheriff, Francis Jourdan. York was re-elected in 1854 and elected to a third term in 1858.

Fast-forward to 1860. In north Texas the Civil War was foreshadowed by an outbreak of violence: arson, lynchings. In Tarrant County two suspected white abolitionists were hanged by vigilantes. One of those lynching victims was William H. Crawford.

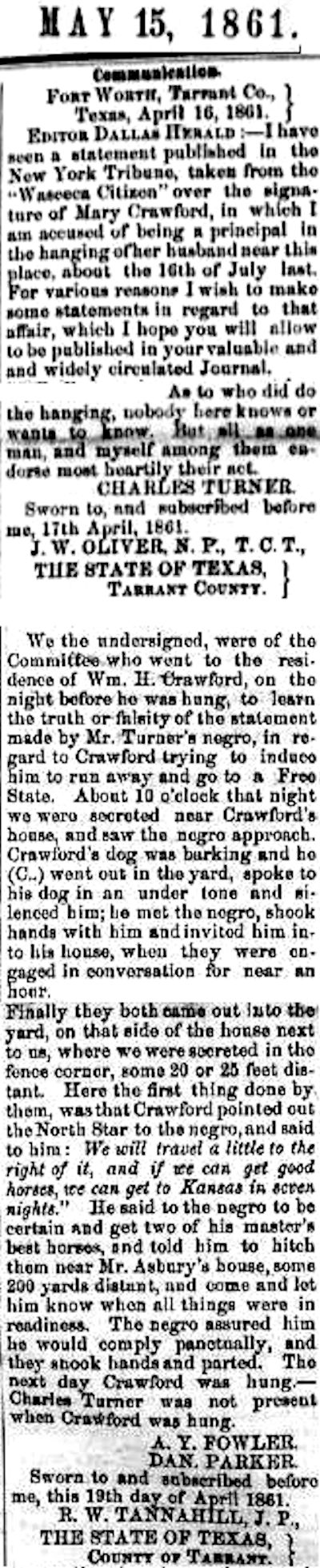

Fast-forward to April 1861. The war had just begun. William Crawford’s widow Mary had accused Charles Turner of taking part in the lynching of her husband. In an open letter printed in the Dallas Herald on May 15, 1861 Turner denied taking part in the lynching (although he “most heartily” endorsed it). In another open letter, Archibald Young Fowler came to the defense of Turner but in doing so apparently implicated himself: Fowler wrote that he had been a member of a “committee” that had spied on Crawford and a slave of Turner in order to determine if Crawford was going to encourage the slave to run away to a free state. Note the last sentence in Fowler’s letter: He wrote that Charles Turner was not present when Crawford was hanged.

Did Archibald Young Fowler know that Turner was not present because Fowler himself was present?

Archibald Young Fowler was an attorney. And a well-placed one: His wife, Juliette, was sister of Carroll Marion Peak, the town’s first doctor. Fowler was even law partners with John Peter Smith. Both men were members of Masonic lodge 148, the town’s first.

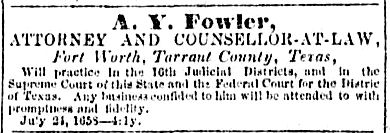

Fowler advertised in the Dallas Weekly Herald in 1861.

Fowler advertised in the Dallas Weekly Herald in 1861.

Archibald Young Fowler was inordinately well outfitted for life in a frontier town: In addition to his law degree and his Masonic membership, he carried a Bowie knife.

And he had a temper.

Fast-forward two months. On July 20, 1861 a barbecue and a military review of Confederate troops were held at the Cold Springs, a popular community gathering place east of today’s Samuels Avenue. The cool water of the springs was popular on that hot day. Impatient, A. Y. Fowler did not wait his turn in line at the springs. John B. York , who was again serving as sheriff, was present. York ordered Fowler to skedaddle to the back of the line. Fowler was humiliated.

Fowler brooded.

A month later, on August 24, John B. York and Archibald Young Fowler encountered each other on a downtown street.

The details of what transpired between York and Fowler on that street have been obscured by the passage of time and by the bias of those telling the story: Descendants of each man blame the other man. Local historians Oliver Knight and Julia Kathryn Garrett trace the trouble between the two men to Birdville-Fort Worth animosity over the county seat issue. Probably the most objective and detailed reconstruction of the facts is in Written in Blood (Volume 1) by local historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster.

Fowler, in the company of his nephew Willie, drew his Bowie knife and attacked York, stabbing him repeatedly. York managed to draw his Colt pistol and shoot Fowler. Willie then leveled his gun—a double-barreled shotgun—and shot York. Then Willie ran to fetch a doctor. That doctor was Carroll Peak, the brother of Fowler’s wife. Dr. Peak, Selcer and Foster write, helped Willie get out of town. The family story is that Willie joined the Confederacy and died in the war.

Dr. Peak helped Willie, but he could not help Fowler and York. Both men died.

Archibald Young Fowler was buried in Dallas.

Archibald Young Fowler was buried in Dallas.

John B. York was buried on the lone prairie, next to his infant son in little Mitchell Cemetery between the railroad tracks.

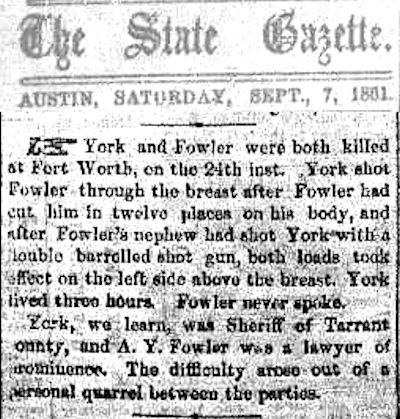

The State Gazette of Austin reported the double killing.

The State Gazette of Austin reported the double killing.

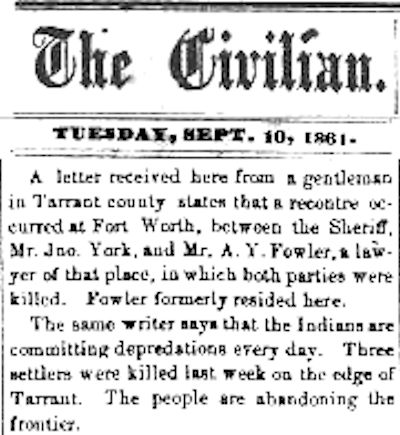

Via a letter from Tarrant County the Civilian of Galveston received news of the killings and of Native American “depredations.”

Via a letter from Tarrant County the Civilian of Galveston received news of the killings and of Native American “depredations.”

John B. York’s first was as sad as his son’s: John York was probably the first Tarrant County law officer to die in the line of duty.

John Peter Smith was among those who signed this tribute to fellow Mason Archibald Young Fowler, which appeared in the Dallas Weekly Herald.

Julia York and Juliette Fowler were pregnant when their husbands met downtown on that hot August day in 1861. The York infant who died in 1848, had he lived, would have been thirteen years old when his father was killed.

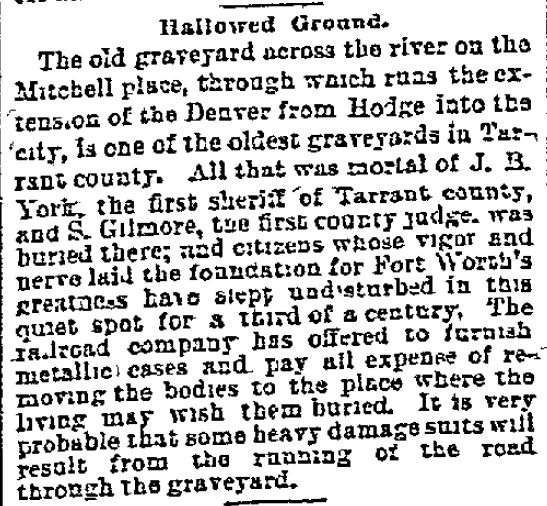

Postscript: In 1890 the Dallas Morning News printed this report. (Contrary to the report, Francis Jourdan, not John B. York, was Tarrant County’s first sheriff.) The report shows that little Mitchell Cemetery was already feeling the pinch of progress by 1890.

There was no more lone prairie.

In 2016 the tombstone of Seaborne Gilmore (left) was joined by two new markers.

In 2016 the tombstone of Seaborne Gilmore (left) was joined by two new markers.

Descendants erected memorials honoring Sheriff York and his infant son.

Descendants erected memorials honoring Sheriff York and his infant son.

To the Administrator of this site. I have some photos from the Mitchell Cemetery that I took in about 1990. I also have a very interesting clipping of a 1949 article from the Fort Worth Star Telegram titled “100 years ago today”. It talks about the birth of Martha Ellen Gilmore, People gathering at the Gilmore cabin, it mentions the York’s baby Will, and other noteworthy points. Would you be interested in posting these?

Unfortunately this site cannot accept any additional content to post.

I visited the Mitchell Cemetery years ago with my father John Frank Gilmore ( deceased ). We found an older version of the headstone for Seaborn Gilmore, and a barely legible sandstone headstone for John B. York… which may have been his original headstone. I am a direct descendent of Seaborn Gilmore. He had a son named Frances Dean Gilmore who was a Civil War veteran. F.D.’s son Frank Milton was my great grandfather. Dan Lamb, are you still around? I would love to know what further history you may know of regarding the ancestors of Seaborn Gilmore. My father researched our history when he could for many years before computers. He believed Seaborn’s grandfather to be Huriah Gilmore, who was a Continental Army veteran, who’s father was Hugh Gilmore from Scotland / Ireland.

How many people total are buried at the Mitchell Cemetery and do you have to cross the tracks to get to the cemetery?

The Tarrant County Historical Society is sure of twelve but says the number could be as high as seventy-five. Early graves were unmarked or are now markerless. Some tombstones have been moved. The cemetery still lies between two railroad tracks. The tracks could be avoided by climbing up the embankment on the south side of Northeast 28th Street north of the cemetery.

Facinating story, love the history of my home town. Thanks for sharing this info.

Thanks, Barbara.

Incredible story!

Thanks, Colleen.

Mike, thank you once again for another wonderful post. The Mitchell has both a personal and professional interest to me. Seaborn’s grandparent’s (John and Jane Heard Gilmore) are my 5th Great Grandparents. I am also a board member of the North Fort Worth Historical Society. As all things in the Northside area and Stockyards specifically, I, or shall I say we are concerned about anything of historical significance. In your research, did you come across any credible information that suggests what is in store for this tiny piece Fort Worth history. I have heard that TXDOT has money in the 28th Street bridge project budget to fence the cemetery to help preserve it. Did you see or hear anything like that? Thanks again for this article and all that you are doing for the preservation of Fort Worth’s wonderful history. Dan Lamb

Thank you, Dan. It’s always nice to hear from descendants of people who made Fort Worth history. I am afraid that you have told me more than I told you. I was not aware of the possibility of Mitchell Cemetery being fenced. I hope that happens. An almost-invisible cemetery in such an unlikely setting needs something to tell people that it’s a special place, not just some barren ground between two railroad tracks.

Does the city ever use ground penetrating radar for grave detection or grave witching to determine how many graves there are or where the placement of a fence should be?

I have an interest in finding other graves in a private cemetery on the west side of Fort Worth.