The year 1860 brought to Tarrant County, to borrow from Shakespeare, the summer of our discontent. As elsewhere in the South during the months leading up to Fort Sumter, in Tarrant County passions ran high as people debated the merits and demerits of union and secession, of slavery and abolition, although sentiments here favored secession and slavery, and suspicions fell hard upon unionists and abolitionists. Fort Worth newspapers of the time are not available, so reports in other newspapers must be relied upon to piece together the situation in Fort Worth on the eve of civil war.

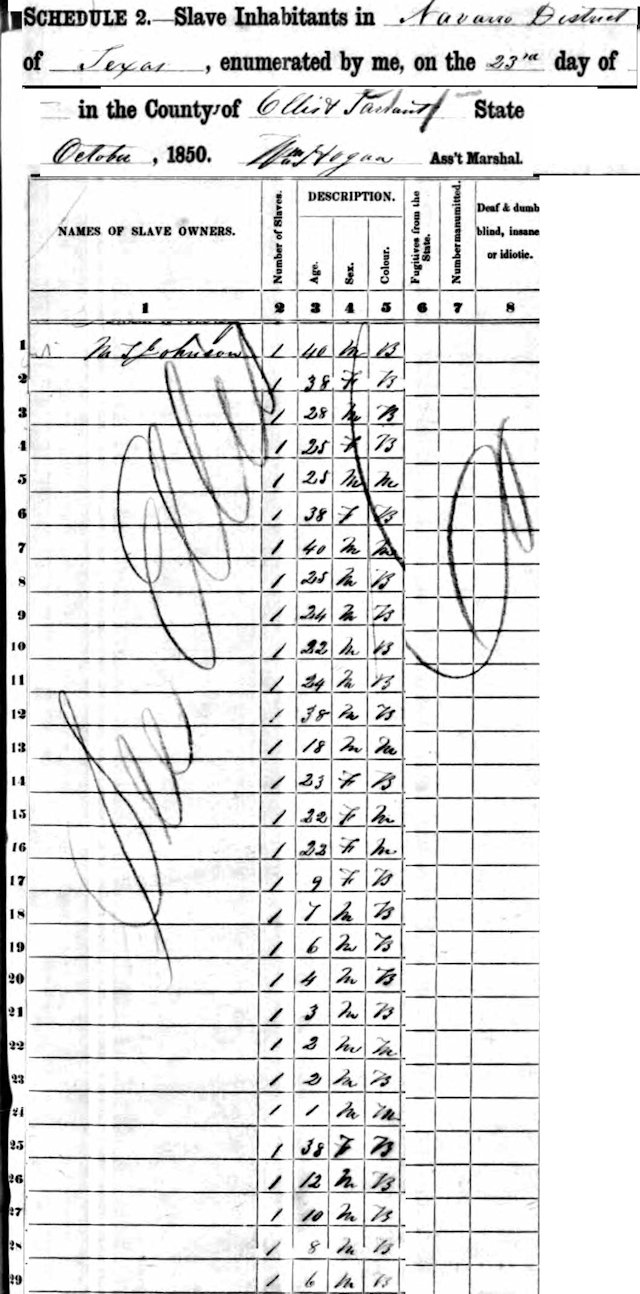

But first some pre-1860 history: Whites in Texas had practiced slavery since the beginning—while Texas was a territory of Mexico (according to the Texas General Land Office, by 1826 25 percent of the population of Stephen F. Austin’s colony were slaves) and then while Texas was a republic. Not surprisingly, when Texas joined the Union in 1845 Texas was admitted as a slave state. Five years later, when Tarrant County’s first census was taken in 1850, historian Julia Kathryn Garrett writes, Tarrant County had sixty-five slaves (and 599 whites). Slaves were listed in the census enumeration by age and gender, not by name. Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson, who owned a plantation in today’s south Arlington, was easily the largest slaveholder in the county in 1850. (Read the memories of one Johnson slave.)

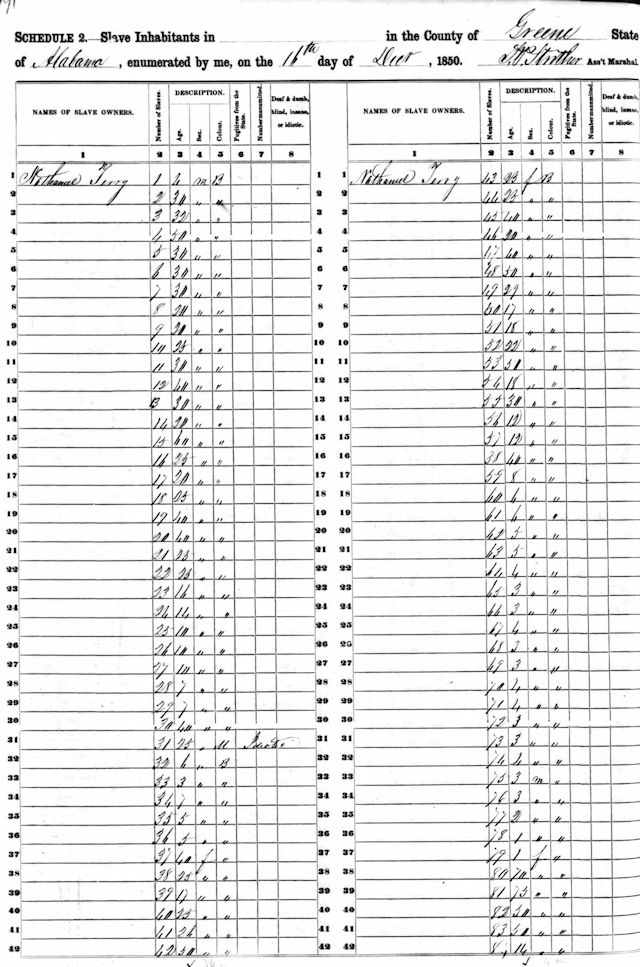

Although not yet a resident of Tarrant County in 1850, in Alabama former president of the Alabama state Senate Colonel Nat Terry owned eighty-four slaves. Terry would move to Fort Worth in 1853 and own a plantation in today’s Samuels Avenue neighborhood. His slaves would build his home (described by B. B. Paddock as “of several rooms snow-white and well furnished”).

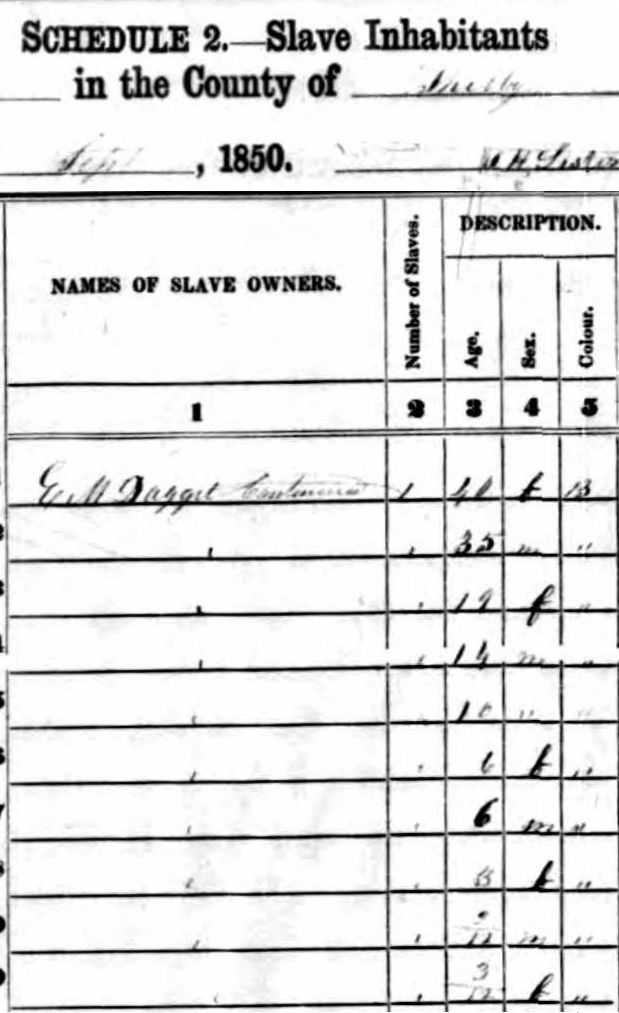

Future Fort Worth civic leader Ephraim Merrell Daggett in 1850 was still living in Shelby County, where he had ten slaves. After he moved to Fort Worth his farm covered much of the south end of today’s downtown. Daggett continued to own slaves, including the mother of Jeff Daggett. Another Tarrant County slave owner was Charles Turner, whose farm was located at today’s Greenwood Cemetery. Historian Garrett says David Mauck, the contractor who built Fort Worth’s second county courthouse, also owned slaves and used them as his construction crew.

Future Fort Worth civic leader Ephraim Merrell Daggett in 1850 was still living in Shelby County, where he had ten slaves. After he moved to Fort Worth his farm covered much of the south end of today’s downtown. Daggett continued to own slaves, including the mother of Jeff Daggett. Another Tarrant County slave owner was Charles Turner, whose farm was located at today’s Greenwood Cemetery. Historian Garrett says David Mauck, the contractor who built Fort Worth’s second county courthouse, also owned slaves and used them as his construction crew.

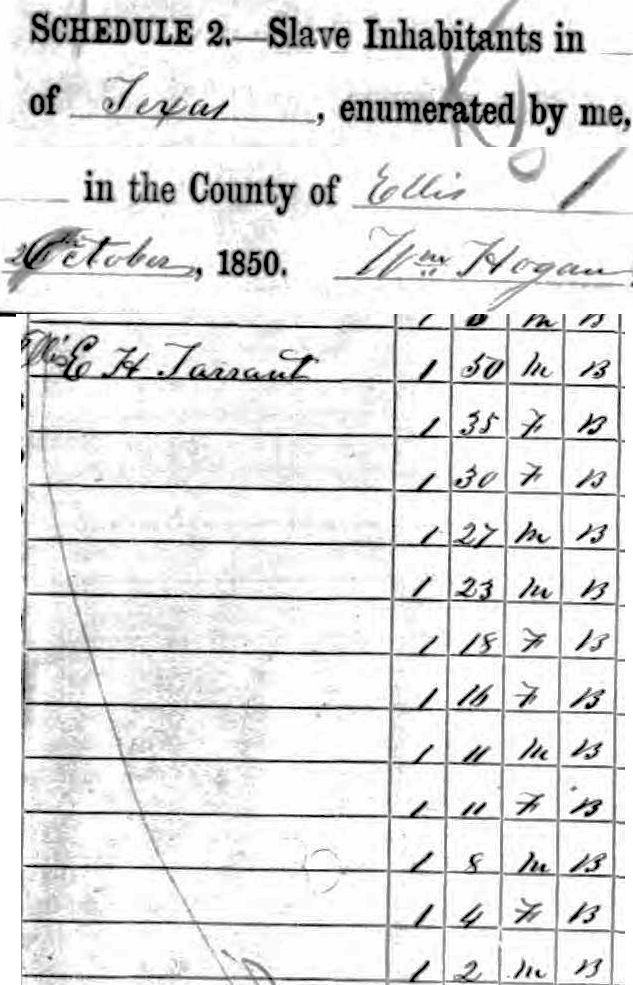

Another slaveholder was General Edward H. Tarrant, namesake of the county, who lived in Ellis County in 1850.

Another slaveholder was General Edward H. Tarrant, namesake of the county, who lived in Ellis County in 1850.

Most local residents, of course, did not own slaves but had settled in Texas from slaveholding states and retained pro-slavery (and/or states’ rights) sentiments.

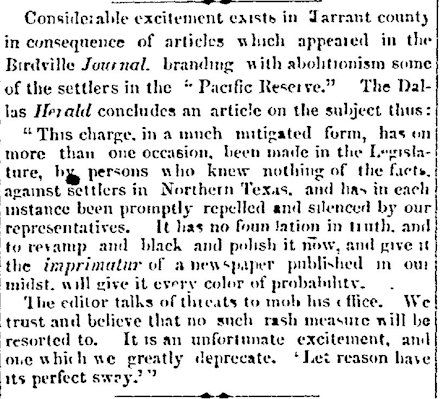

Also living in pro-slavery Texas—albeit precariously—were abolitionists. For example, in 1858 the Birdville Journal claimed that abolitionists were living in the “Pacific Reserve.” That was the Missouri and Pacific Railroad Land Reserve in Texas, which was being settled for fifty cents an acre. The Dallas Weekly Herald disputed the Journal’s claim of abolitionists. The Birdville Journal seems to have had a short life. A profusion of small, partisan newspapers sprang up before the Civil War to promote their views on slavery and states’ rights. Clip is from the May 1, 1858 San Antonio Ledger.

Also living in pro-slavery Texas—albeit precariously—were abolitionists. For example, in 1858 the Birdville Journal claimed that abolitionists were living in the “Pacific Reserve.” That was the Missouri and Pacific Railroad Land Reserve in Texas, which was being settled for fifty cents an acre. The Dallas Weekly Herald disputed the Journal’s claim of abolitionists. The Birdville Journal seems to have had a short life. A profusion of small, partisan newspapers sprang up before the Civil War to promote their views on slavery and states’ rights. Clip is from the May 1, 1858 San Antonio Ledger.

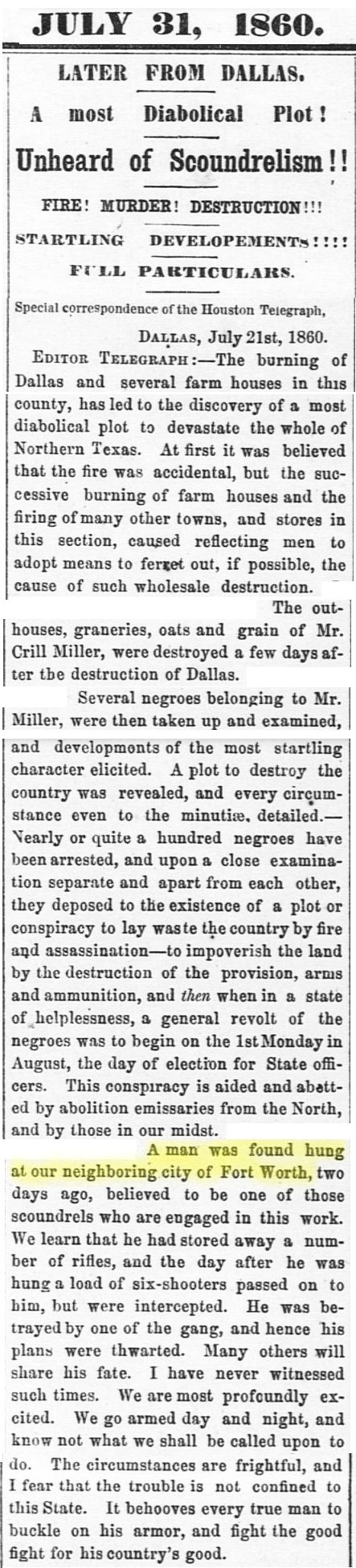

Then came 1860. “Unheard of Scoundrelism” was the cry in one newspaper headline after suspicious fires broke out in several north Texas counties—including Tarrant and Dallas—in the summer of 1860. Vigilance committees accused abolitionists of a “diabolical plot to devastate the whole of Northern Texas.” The July 31 Houston Telegraph wrote: “It behooves every true man to buckle on his armor, and fight the good fight for his country’s good.”

Then came 1860. “Unheard of Scoundrelism” was the cry in one newspaper headline after suspicious fires broke out in several north Texas counties—including Tarrant and Dallas—in the summer of 1860. Vigilance committees accused abolitionists of a “diabolical plot to devastate the whole of Northern Texas.” The July 31 Houston Telegraph wrote: “It behooves every true man to buckle on his armor, and fight the good fight for his country’s good.”

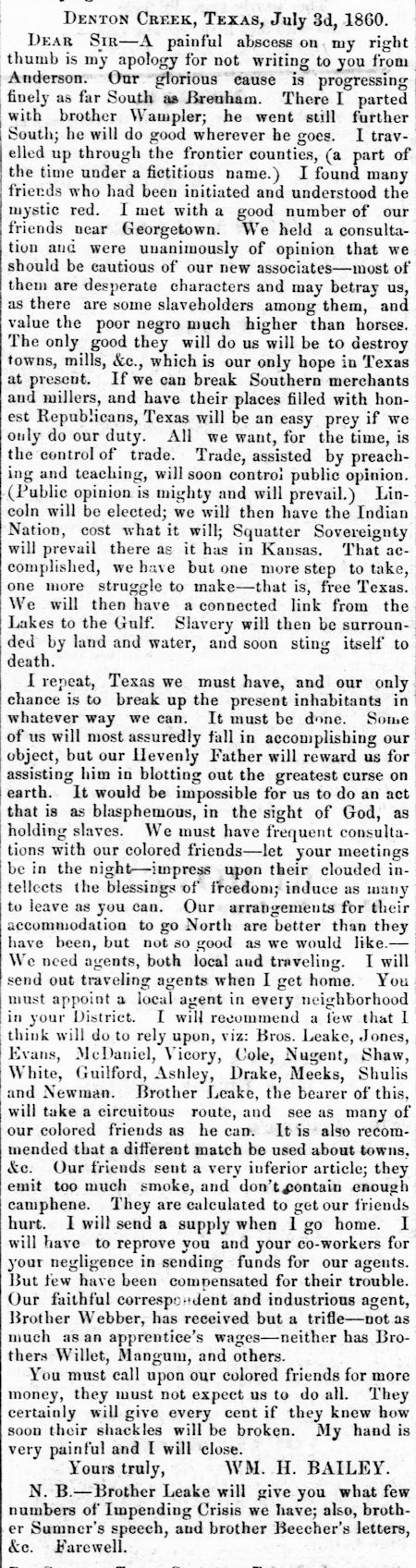

Anthony Bewley was born in 1804 in Tennessee but by 1858 was living in Johnson County south of Fort Worth. Bewley was a Northern Methodist minister, opposed slavery, endorsed abolition. Those views did not set well with many folks in these parts. After the “unheard of scoundrelism” began, suspicion quickly fell upon Bewley and other abolitionists, especially after two Tarrant County men found a letter, dated July 3, 1860 and written from Denton Creek. The letter was addressed to a Reverend William Bewley and supposedly was written by a fellow abolitionist, W. H. Bailey. The letter urged Bewley to continue his abolition work in Texas. The writer mentioned “our glorious cause” and the “Mystic Red” abolitionist organization and said, “If we can break Southern merchants and millers, and have their places filled by honest Republicans, Texas will be an easy prey, if we only do our duty.” “Our Heavenly Father will reward us for helping him in blotting out the greatest curse on earth.” The letter also mentioned arson, calling for “a different material to be used about town, etc. Our friends sent a very inferior article; they emit too much smoke, and do not contain enough camphene,” a combustible liquid.

Anthony Bewley was born in 1804 in Tennessee but by 1858 was living in Johnson County south of Fort Worth. Bewley was a Northern Methodist minister, opposed slavery, endorsed abolition. Those views did not set well with many folks in these parts. After the “unheard of scoundrelism” began, suspicion quickly fell upon Bewley and other abolitionists, especially after two Tarrant County men found a letter, dated July 3, 1860 and written from Denton Creek. The letter was addressed to a Reverend William Bewley and supposedly was written by a fellow abolitionist, W. H. Bailey. The letter urged Bewley to continue his abolition work in Texas. The writer mentioned “our glorious cause” and the “Mystic Red” abolitionist organization and said, “If we can break Southern merchants and millers, and have their places filled by honest Republicans, Texas will be an easy prey, if we only do our duty.” “Our Heavenly Father will reward us for helping him in blotting out the greatest curse on earth.” The letter also mentioned arson, calling for “a different material to be used about town, etc. Our friends sent a very inferior article; they emit too much smoke, and do not contain enough camphene,” a combustible liquid.

Many people believed that the letter was a forgery written by slavery partisans to foment violence against abolitionists. But others interpreted the letter as proof that the Reverend Anthony Bewley was in cahoots with abolitionists in Texas. This clip is from the Charlotte, North Carolina, Western Democrat of October 16, 1860.

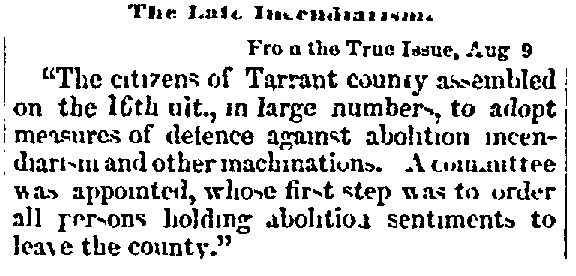

On August 18, 1860 the Texas State Gazette (edited by the staunchly proslavery and antiabolitionist John Marshall) quoted the True Issue, a La Grange weekly, as reporting that Tarrant County residents had met to discuss taking measures against “abolition incendiarism” and advising abolitionists to skedaddle.

On August 18, 1860 the Texas State Gazette (edited by the staunchly proslavery and antiabolitionist John Marshall) quoted the True Issue, a La Grange weekly, as reporting that Tarrant County residents had met to discuss taking measures against “abolition incendiarism” and advising abolitionists to skedaddle.

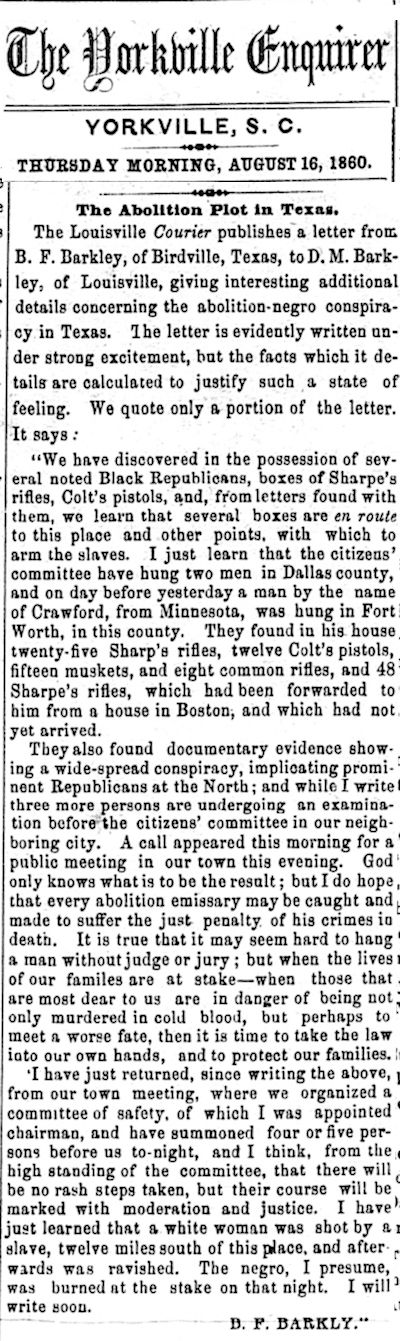

One abolitionist who didn’t skedaddle was William H. Crawford. On August 16, 1860 the Yorkville, South Carolina, Enquirer, reporting on the “abolition-negro conspiracy in Texas,” reported that the Louisville Courier had printed the letter of a Birdville man who said Crawford had been found in possession of weapons “with which to arm the slaves.”

One abolitionist who didn’t skedaddle was William H. Crawford. On August 16, 1860 the Yorkville, South Carolina, Enquirer, reporting on the “abolition-negro conspiracy in Texas,” reported that the Louisville Courier had printed the letter of a Birdville man who said Crawford had been found in possession of weapons “with which to arm the slaves.”

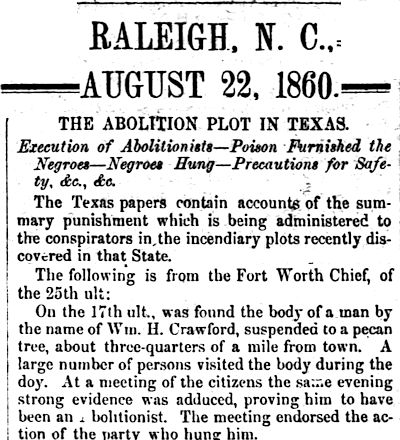

The Raleigh, North Carolina Weekly Standard quoted A. B. Norton’s Fort Worth Chief: Crawford had been lynched near Fort Worth. The short-lived Chief was Fort Worth’s first newspaper; Norton was a unionist. The Chief said that Crawford had been hanged from a pecan tree three-quarters of a mile from town and that a citizens committee had “endorsed the action of the party who hung him.” In his autobiography, Force Without Fanfare, Major K. M. Van Zandt said that later in 1860 Norton packed up his press and left town because his antislavery views were not popular.

The Raleigh, North Carolina Weekly Standard quoted A. B. Norton’s Fort Worth Chief: Crawford had been lynched near Fort Worth. The short-lived Chief was Fort Worth’s first newspaper; Norton was a unionist. The Chief said that Crawford had been hanged from a pecan tree three-quarters of a mile from town and that a citizens committee had “endorsed the action of the party who hung him.” In his autobiography, Force Without Fanfare, Major K. M. Van Zandt said that later in 1860 Norton packed up his press and left town because his antislavery views were not popular.

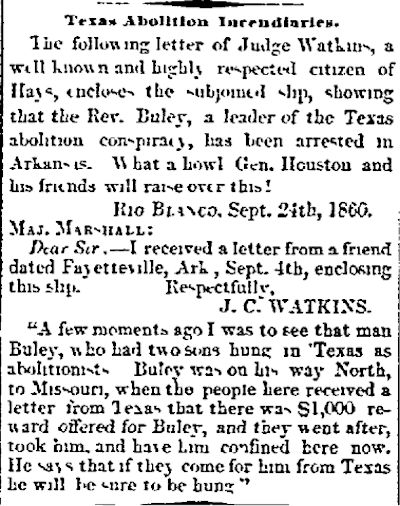

On September 29, 1860 the Texas State Gazette reprinted a letter from a man in Arkansas saying that the Reverend Bewley, now with a $1,000 reward on his head, had been arrested and jailed in Arkansas.

On September 29, 1860 the Texas State Gazette reprinted a letter from a man in Arkansas saying that the Reverend Bewley, now with a $1,000 reward on his head, had been arrested and jailed in Arkansas.

While under detention Bewley wrote to his wife from Fayetteville: “I never took up my pen under such circumstances before. . . . They have not put me in jail, but keep me under guard. At night I am chained fast to some person, and in the day I have liberty to walk about with the guard. . . . I suppose they will set out with us to Texas on the overland stage, and if so, hand us over to the Fort Worth Committee and receive the reward. Then we will, I suppose, be under their supervision, to do with us as seemeth them good. And if that takes place, dear and much beloved wife and loving children, I shall never, in this life, expect to see you; but I shall look to meet you all, with our little babe that has already gone to that blessed haven of repose.”

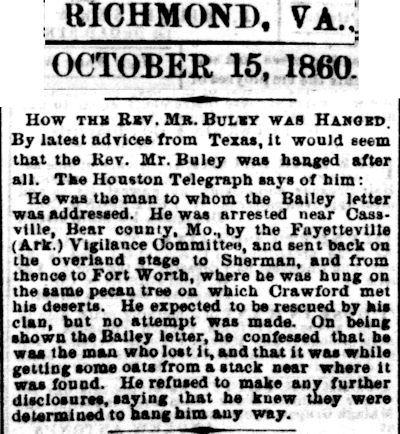

Bewley’s fear was well founded. On October 15 the Richmond, Virginia Daily Dispatch reported that the Houston Telegraph said Bewley had been returned to Fort Worth. Bewley, like Crawford, was lynched.

Bewley’s fear was well founded. On October 15 the Richmond, Virginia Daily Dispatch reported that the Houston Telegraph said Bewley had been returned to Fort Worth. Bewley, like Crawford, was lynched.

Historian Oliver Knight in Fort Worth: Outpost on the Trinity writes that Bewley, accused of “implication in a nefarious plot to poison wells, fire towns and residences, and in the midst of conflagration and death, to run off with the slaves,” was lynched on a tree west of town—next to the dangling body of suspected abolitionist Crawford. Knight wrote that “The two men were held in such hatred that neither was ever given the dignity of burial. Suspended from rotting ropes, their bodies became skeletons hanging in the breeze.”

Historian Oliver Knight in Fort Worth: Outpost on the Trinity writes that Bewley, accused of “implication in a nefarious plot to poison wells, fire towns and residences, and in the midst of conflagration and death, to run off with the slaves,” was lynched on a tree west of town—next to the dangling body of suspected abolitionist Crawford. Knight wrote that “The two men were held in such hatred that neither was ever given the dignity of burial. Suspended from rotting ropes, their bodies became skeletons hanging in the breeze.”

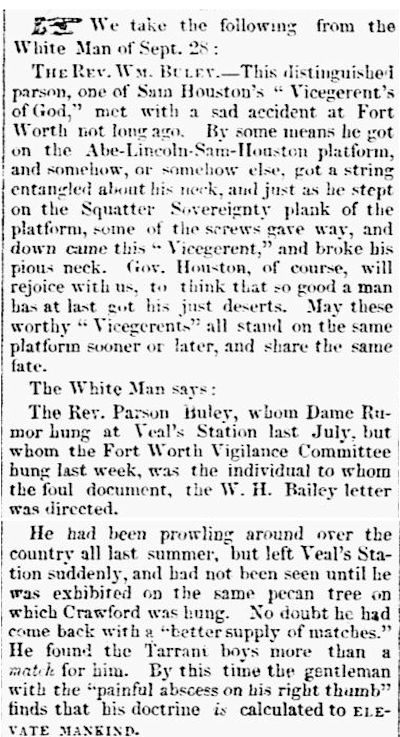

On September 29 the Texas State Gazette reprinted the mocking report of the Bewley lynching in the White Man, a secessionist newspaper in Jacksboro. (Veal’s Station was in Parker County, but Bewley was hanged much closer to Fort Worth.)

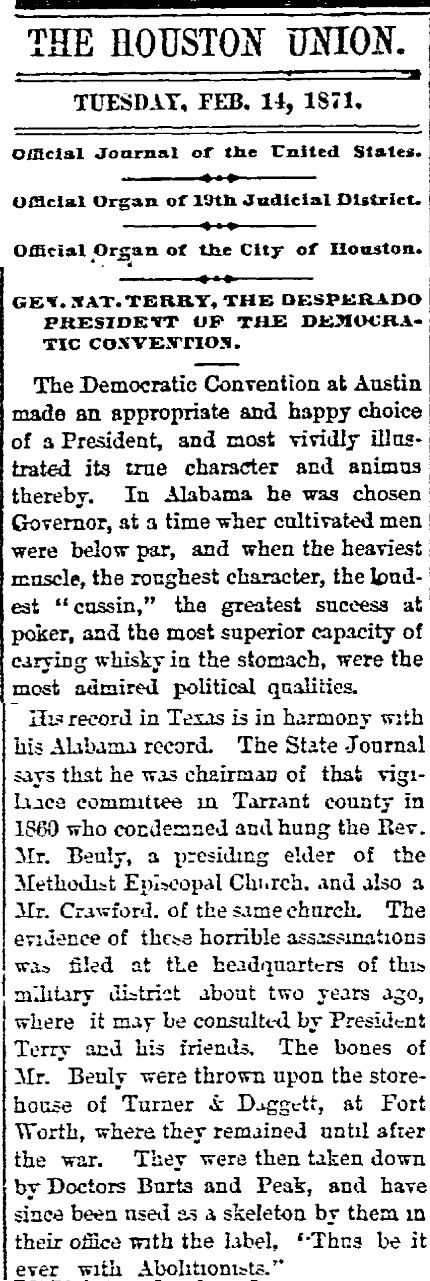

(Culpability for the Bewley and Crawford lynchings would be debated for years. In 1871, after Nat Terry had been elected president of the state Democratic convention, the Houston Union quoted the State Journal as claiming that Terry had been chairman of the vigilance committee that had hanged the two men. The report mentions the store of Charles Turner and Henry Clay Daggett and the office of physicians William Paxton Burts and Carroll Peak. [Contrary to this report, Nat Terry had lost his bid for the Alabama governorship.])

(Culpability for the Bewley and Crawford lynchings would be debated for years. In 1871, after Nat Terry had been elected president of the state Democratic convention, the Houston Union quoted the State Journal as claiming that Terry had been chairman of the vigilance committee that had hanged the two men. The report mentions the store of Charles Turner and Henry Clay Daggett and the office of physicians William Paxton Burts and Carroll Peak. [Contrary to this report, Nat Terry had lost his bid for the Alabama governorship.])

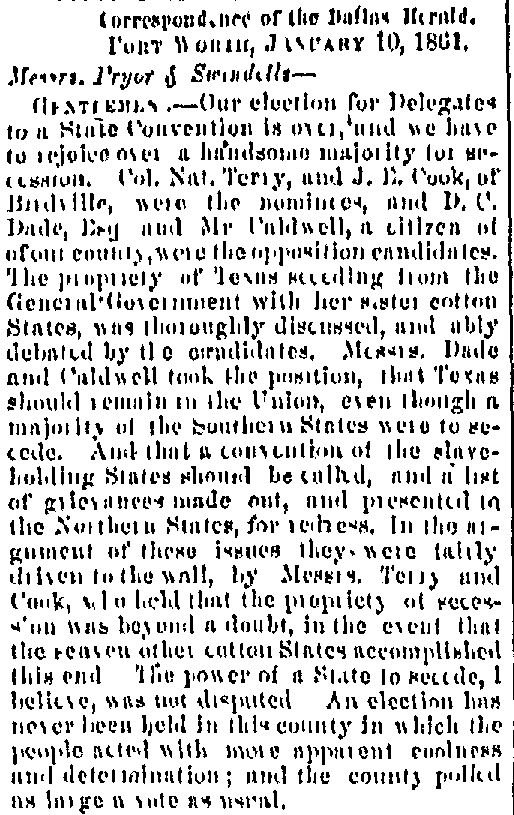

By the new year 1861, much had happened. Lincoln had been elected president in November 1860. South Carolina had seceded in December. Before the end of January five more southern “cotton states” would secede. On January 16, 1861 the Dallas Herald reported that a delegation in Tarrant County had elected two secessionist delegates to the state convention on secession. One delegate was Nat Terry, “who held that the propriety of secession was beyond a doubt, in the event that the seven other cotton States accomplished this end.” (Pryor and Swindells were editor and publisher of the Herald.)

By the new year 1861, much had happened. Lincoln had been elected president in November 1860. South Carolina had seceded in December. Before the end of January five more southern “cotton states” would secede. On January 16, 1861 the Dallas Herald reported that a delegation in Tarrant County had elected two secessionist delegates to the state convention on secession. One delegate was Nat Terry, “who held that the propriety of secession was beyond a doubt, in the event that the seven other cotton States accomplished this end.” (Pryor and Swindells were editor and publisher of the Herald.)

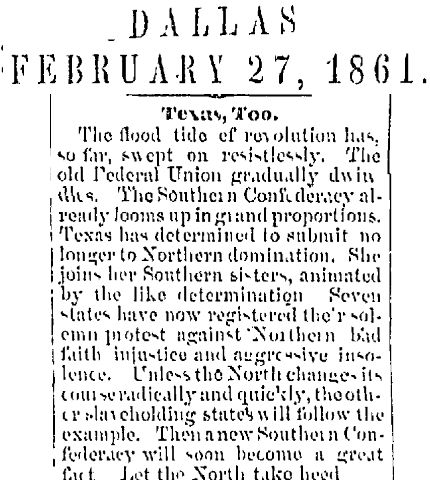

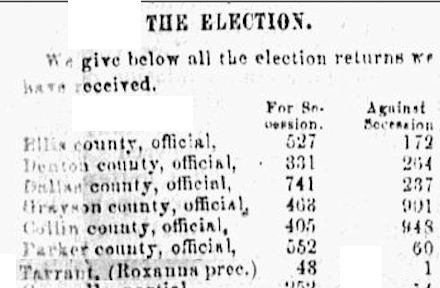

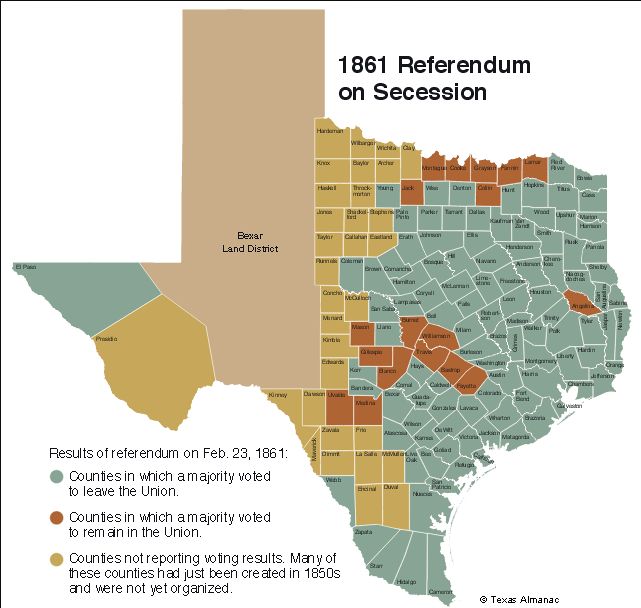

On February 23, 1861 Texans (men only) went to the polls to vote in a referendum for or against secession. The results: 46,153 for and 14,747 against. Texas at the time was estimated to have a population of 421,649 free people and 182,566 slaves. Only eighteen counties of 122 voting rejected secession. On February 27, although the vote totals were not yet final, the Dallas Weekly Herald wrote that “The Southern Confederacy already looms up in grand proportions.”

On February 23, 1861 Texans (men only) went to the polls to vote in a referendum for or against secession. The results: 46,153 for and 14,747 against. Texas at the time was estimated to have a population of 421,649 free people and 182,566 slaves. Only eighteen counties of 122 voting rejected secession. On February 27, although the vote totals were not yet final, the Dallas Weekly Herald wrote that “The Southern Confederacy already looms up in grand proportions.”

On March 6 the Dallas Weekly Herald reported that Tarrant County vote totals were still incomplete, but the Journal of the Secession Convention listed Tarrant County’s final vote count as 462 for secession and 127 against.

On March 6 the Dallas Weekly Herald reported that Tarrant County vote totals were still incomplete, but the Journal of the Secession Convention listed Tarrant County’s final vote count as 462 for secession and 127 against.

Pioneer Fort Worth attorney J. C. Terrell in his memoirs remembered the vote differently. He said Tarrant County approved secession by a margin of only twenty-seven out of eight hundred votes cast. He said that such men as he, John Peter Smith, and District Attorney Dabney C. Dade “voted with Gen. Sam Houston against secession.” Nonetheless, when war came, Terrell and Smith fought for the Confederacy. Dade, who had been Terrell’s schoolmate and law partner, “refused to take the oath to the Confederacy” and “went back North.”

On March 2—Texas Independence Day and Sam Houston’s birthday—the discontent of the previous summer yielded to dissolution: Texas secession from the Union became official.

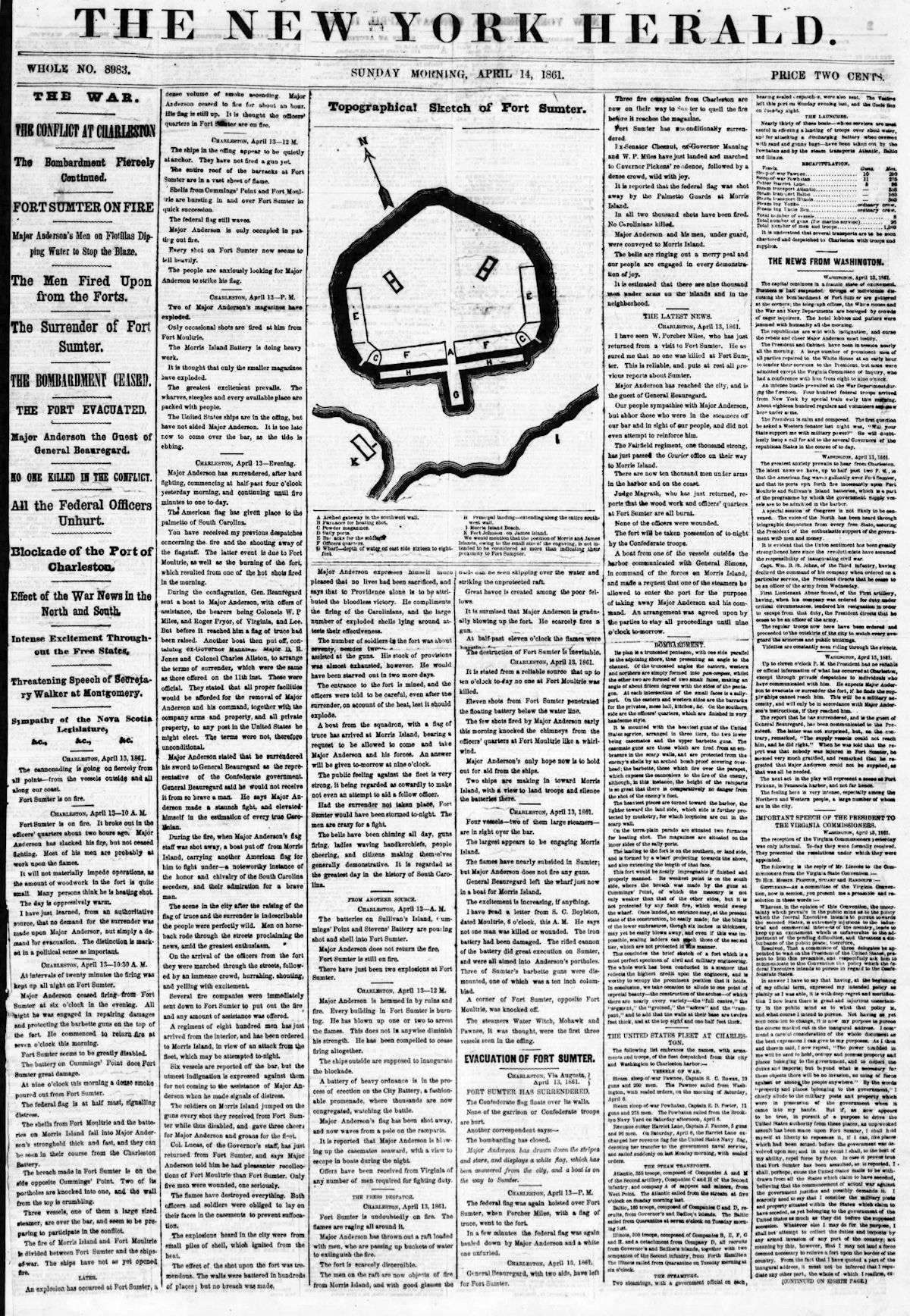

Then came April 12 and the Battle of Fort Sumter in South Carolina: “The War Begun.”

Then came April 12 and the Battle of Fort Sumter in South Carolina: “The War Begun.”

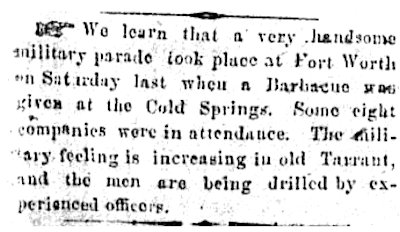

On July 24, 1861 the Dallas Weekly Herald reported a military parade during a barbecue at the Cold Springs east of today’s Samuels Avenue. “The military feeling is increasing in old Tarrant, and the men are being drilled by experienced officers.”

On July 24, 1861 the Dallas Weekly Herald reported a military parade during a barbecue at the Cold Springs east of today’s Samuels Avenue. “The military feeling is increasing in old Tarrant, and the men are being drilled by experienced officers.”

After the war began, although Texas soil largely avoided military clashes, especially when compared with states east of the Mississippi River, civilian tensions continued over the issues of secession and abolition. In the secession referendum in February 1861 Cooke County had been among seven counties on or near the Red River that had voted to remain in the Union. (Map from Texas Almanac.)

After the war began, although Texas soil largely avoided military clashes, especially when compared with states east of the Mississippi River, civilian tensions continued over the issues of secession and abolition. In the secession referendum in February 1861 Cooke County had been among seven counties on or near the Red River that had voted to remain in the Union. (Map from Texas Almanac.)

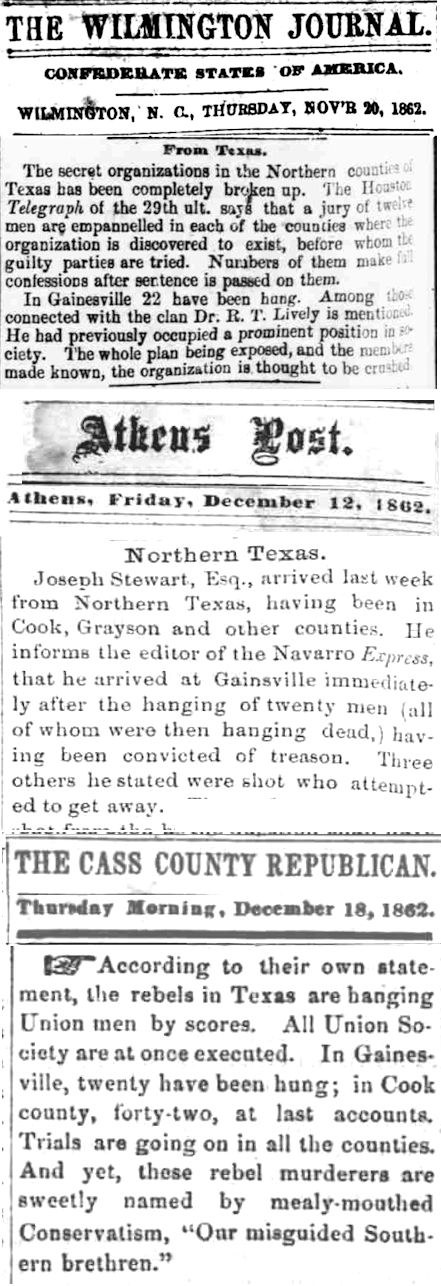

In Cooke County the referendum vote had been more than 70 percent against secession. During the Great Hanging at Gainesville (Cooke County) in October 1862, vigilantes hanged forty-one suspected unionists. Some of the forty-one were convicted by a kangaroo court; some were hanged without a trial. Some were acquitted but then retried, convicted, and hanged. These newspaper clips are from the Wilmington, North Carolina Journal, Athens, Tennessee Post, and Cass County, Michigan Republican.

In Cooke County the referendum vote had been more than 70 percent against secession. During the Great Hanging at Gainesville (Cooke County) in October 1862, vigilantes hanged forty-one suspected unionists. Some of the forty-one were convicted by a kangaroo court; some were hanged without a trial. Some were acquitted but then retried, convicted, and hanged. These newspaper clips are from the Wilmington, North Carolina Journal, Athens, Tennessee Post, and Cass County, Michigan Republican.

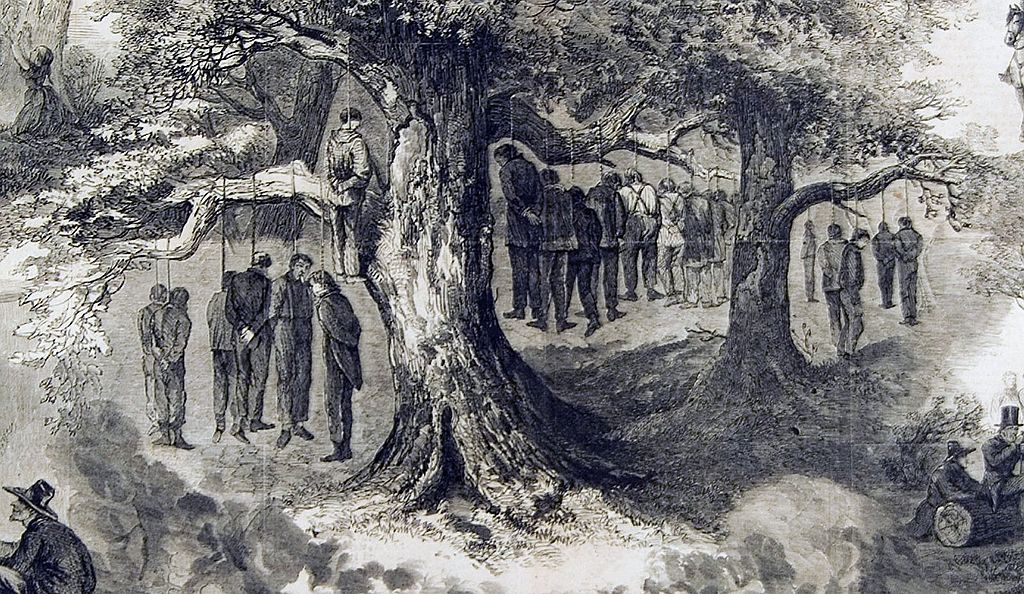

The Great Hanging has been called the largest mass hanging in American history. (Illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper from Wikipedia.)

The Great Hanging has been called the largest mass hanging in American history. (Illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper from Wikipedia.)

Not until March 30, 1870 would Texas be readmitted to the Union.

Oh my these articles are difficult to read, and this information will probably never be used by teachers today. Not trying to be political here, but in reality are we ever privy to the whole story? I am 75 yrs old and grew up one county over from Gainesville and the first I heard about the Great Hangings there was about four years ago through my own research. It angered me that I wasn’t given this info in high school letting me decide how I felt about it. Your research is amazing as usual Mike. Thank you.

Thanks, Jane.

This is a very good account that should of been addressed 25 years ago when the issue of slaves hung in Dallas were falsely accused of burning the town down when in fact there were towns all over having some of the same events that point to the confirmed abolitionist theory that has been confused for over 130 years…thank you for helping come to some understanding in 2018 on what is to become another event soon on how do we resolve these old problems of understanding…A.Troup research historian Dallas Texas…a native and a Catholic.

It is hard to forget the destruction of homes and property, to forget the rape and murder of citizens by the Union soldiers acting under that cherished article (Presidential Executive Order) that makes heroes out of men like Sherman who looted, pillaged and burned anything Union army could not carry away, or slaveholders like Ulysses S Grant (who had to be forced to release his slaves claiming good help is hard to find).

Treason is among the highest crimes and is punishable by death. Traitors are then reserved a special place in Dante’s most inner circle of the Pit. Confederates are Judases in puke-gray coats. The South’s plans to move their enterprises into Mexico and South America should have been carried out by force.

Alas, the better angels of the Union’s nature allowed for these criminals to return, and some would still disagree with that. There’s also the little bit about the blood of traitors’ descendants not being corrupted, but we all carry a little of our fathers’ sins. Also, your point about U.S. Grant is misleading at best and patently false any other way you look at it.

He never said the quote you mention, and there is only definitive proof that he owned one slave. A man by the name William Jones who was freed by Grant in 1859. Your sore-loser Antebellum nostalgia reeks.

wow, even 150 years later you can find racist piece of shit confederacy apologists.

Concerning the hanging of H. Crawford in Ft Worth in Aug 1860. I had a cousin there in Ft Worth, he had arrived from Bristol VA. He wrote home about the incident. He said 5 or 6 Texas towns had been fired up, and because of the summer’s drought, the towns almost burned to nothing. Crawford tried to hire a negro to kill a local merchant and set the town on fire. The negro told his master, so a group of men sent the negro back to Crawford and listened as Crawford gave him instructions. Crawford was followed out of town as he left in the morning and hung. 60 Negreos and abolitionists were also hung in Dallas that same month as they plotted to kill all the women & children, burn the town, and make their escape.

This is all very interesting as most Southerners blame the war on the Merrill Tariff and claim the freeing of the negroes didn’t even enter Lincoln’s mind until he was found to be losing the war. Even then the Emancipation Proclamation (1864?) only freed slaves in the states that had seceded and not any of the Northern slave states. Lincoln hoped the freed slaves would kill their Southern masters and provide him with more troops. ( i.e., how do you free slaves in states that are no longer part of the Union?) It’s all very interesting!!

I bet you did hometown. It is the most comprehensive collection of articles and information I have read about his lynching. I grew up hearing about it from my father. my grandfather was also a circuit rider as were his 2 brothers and my great and great great grandfather too. The church split over slavery of course, and my father told me Bewley must have really pissed off the church to be sent all the way down to Texas, because my family at that time was all centered around Indiana, Kansas and Missouri. i have an old yellowed original news clipping, the obituary of my great grandmother Hannah. It says at the base “her mother was the sister of Rev. Anthony Bewley” and then goes on the reference his lynching. There is no date on the clipping other the Jan. 22 — but i think it is from 1916, the same year my father was born. When I read this obituary, only then did I realize the story my father told me about as I was growing up was not just a family story but was a somewhat famous story or else it would not have been referenced over 50 years later in the news clipping as if Bewley was well known. So I have tried to piece together the events for the last few years. This is the first time I ever read the text of the “Rev. Bailey” letter that I read about. Thanks again.

I’ve been researching Quantrill’s Raiders for a blog post on January 25 about a Fort Worth man who was a member of the guerrilla band during the Civil War. The North-South animosity is startling today, especially considering that the war was essentially Americans against Americans, not Americans against foreign invaders. Some people, such as William Wyeth James (cousin of Jesse and Frank), never forgave and forgot.

I greatly appreciate this collection of news articles. Rev. Bewley was the brother of my great great grandmother Catherine Bewley McClure.

Thanks, Annie. I learned a lot researching that.

There is a comment in the Marshall Texas Republican from August 18th 1860 that Templeton Hensley and Kirk were hung in Gainsville, Tx near August 13th 1860 for being Abolitionists. I have a feeling that that was my great great great grandad. His sons had begun a ranch in Bowie county stock raising and had their brother James Hensley obtain land in Denton County in 1864. James and his brother were close friends with Felix McKittrick and ran cattle from Texarkana area to the Denton Area to go to Kansas. Previously they ran cattle to New Orleans. I need help. I think this man was my family, but there is little info to go on.

Corey: My research has been confined to my area. In case you have not tried them, here are some resources on Gainesville:

Sam Hanna Acheson and Julia Ann Hudson O’Connell, eds., George Washington Diamond’s Account of the Great Hanging at Gainesville, 1862 (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1963).

L. D. Clark, A Bright Tragic Thing (El Paso: Cinco Punto Press, 1992).

L. D. Clark, ed., Civil War Recollections of James Lemuel Clark (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1984).

Michael Collins, Cooke County, Texas: Where the South and West Meet (Gainesville, Texas: Cooke County Heritage Society, 1981).

McCaslin, Richard B. Tainted Breeze: The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas 1862 (Louisiana State University Press, 1994).