In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Fort Worth had several streetcar companies in addition to the interurban to Dallas and to Cleburne. Such mass transit was popular at a time when most people did not own an automobile. To motivate folks even more to become passengers the interurban company and some streetcar companies built “trolley parks” on their lines. These parks were the Six Flags Over Texases and Disney Worlds of their day: popular destinations for families, lodges, unions, companies, and public school classes.

For a brief time early in the twentieth century, Fort Worth had four trolley parks. The first was Rosedale Pavilion (1885-1907) on Samuels Avenue, opened by the Rosedale streetcar line to anchor the northern end of its line, which ran south to the Missouri Pacific Infirmary. Next came Lake Como on the Arlington Heights streetcar line in 1890, Lake Erie on the interurban line in 1903, and White City on Sam Rosen‘s streetcar line in 1906.

By the early twentieth century Fort Worth’s first trolley park, Rosedale Park, was called “Grunewald Park.” Owner Peter Grunewald did not advertise much in local newspapers, but his grand opening ball of the 1903 season did get into the Fort Worth Telegram’s daily column “City in Brief,” which contained as many ads as news items. The running ad for Nash Hardware Company did not even get a complete sentence. Charles E. Nash probably paid to have his company’s name appear at the top of the column each day.

By the early twentieth century Fort Worth’s first trolley park, Rosedale Park, was called “Grunewald Park.” Owner Peter Grunewald did not advertise much in local newspapers, but his grand opening ball of the 1903 season did get into the Fort Worth Telegram’s daily column “City in Brief,” which contained as many ads as news items. The running ad for Nash Hardware Company did not even get a complete sentence. Charles E. Nash probably paid to have his company’s name appear at the top of the column each day.

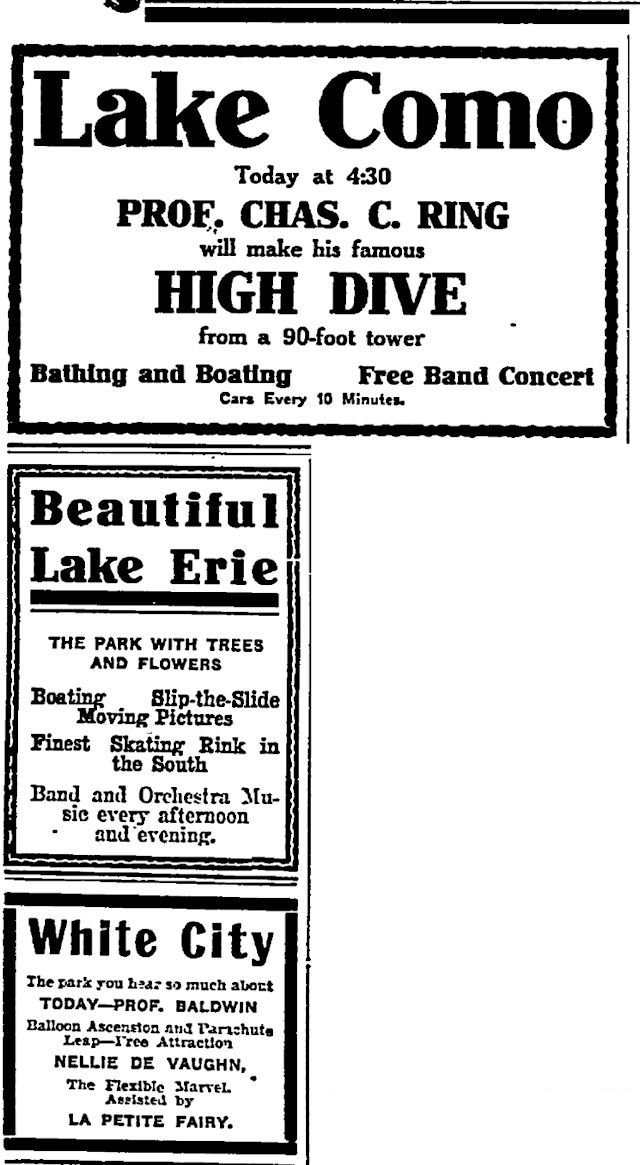

By 1906 ads for the other three trolley parks—Lake Como, Lake Erie, and White City—could be read on the same page of the Telegram, such as on August 5. Water sports and band concerts were common attractions at all the trolley parks. Note that the White City ad mentions Nellie de Vaughn. Two days later the “queen of the clouds” would be dead.

By 1906 ads for the other three trolley parks—Lake Como, Lake Erie, and White City—could be read on the same page of the Telegram, such as on August 5. Water sports and band concerts were common attractions at all the trolley parks. Note that the White City ad mentions Nellie de Vaughn. Two days later the “queen of the clouds” would be dead.

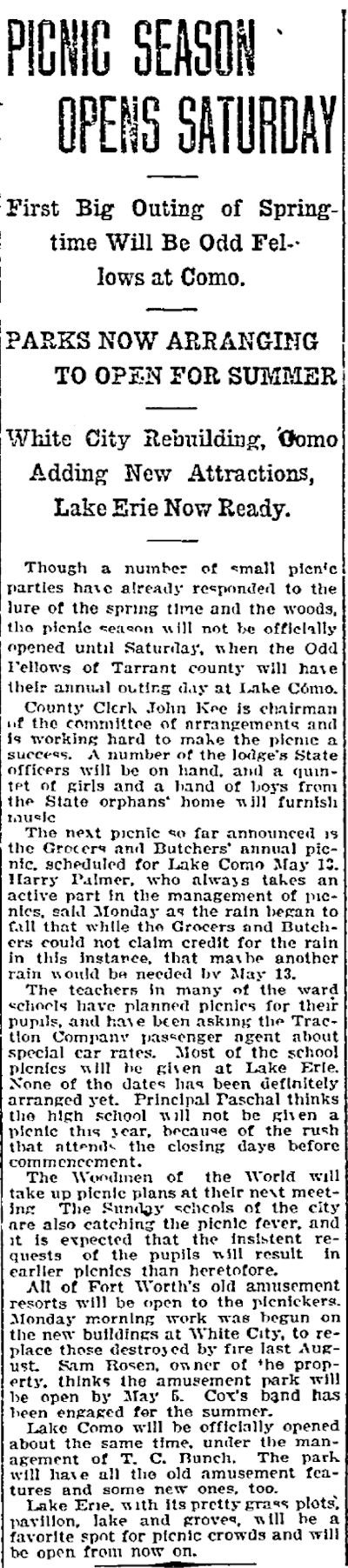

After Rosedale Pavilion closed in 1907, each year at the start of the “picnic season” the Telegram also published a preview of the three parks. Clip is from April 20, 1908.

After Rosedale Pavilion closed in 1907, each year at the start of the “picnic season” the Telegram also published a preview of the three parks. Clip is from April 20, 1908.

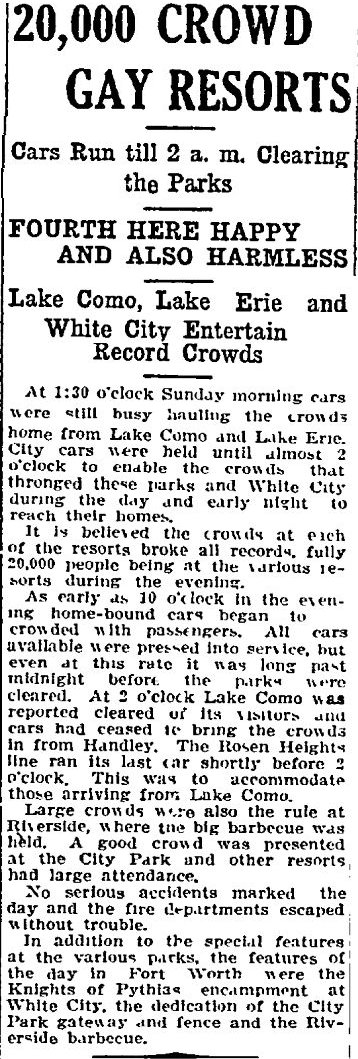

And each July 5 the Telegram printed a roundup of the Independence Day fun at the trolley parks. Streetcars ran into the early morning. Clip is from 1908.

And each July 5 the Telegram printed a roundup of the Independence Day fun at the trolley parks. Streetcars ran into the early morning. Clip is from 1908.

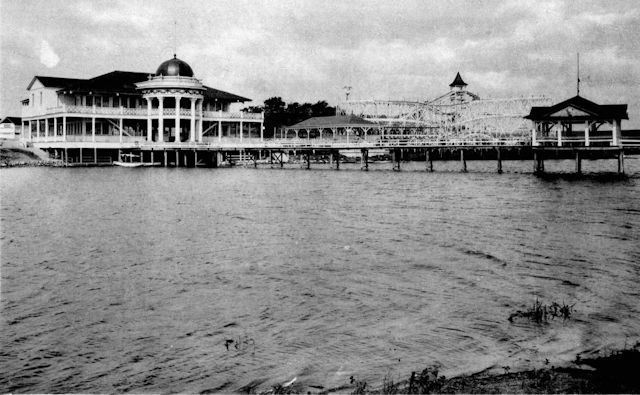

Let’s take a virtual trip out to Lake Como trolley park. The story of Lake Como trolley park is inseparable from the history of Arlington Heights. Lake Como was the creation of Denver developer Humphrey Barker Chamberlin, a British-born capitalist who in 1889 bought almost four thousand acres of prairie west of Fort Worth and began developing his Arlington Heights suburb, envisioning it as an upscale suburb similar to his development in Denver. (Photo from Amon Carter Museum.)

Let’s take a virtual trip out to Lake Como trolley park. The story of Lake Como trolley park is inseparable from the history of Arlington Heights. Lake Como was the creation of Denver developer Humphrey Barker Chamberlin, a British-born capitalist who in 1889 bought almost four thousand acres of prairie west of Fort Worth and began developing his Arlington Heights suburb, envisioning it as an upscale suburb similar to his development in Denver. (Photo from Amon Carter Museum.)

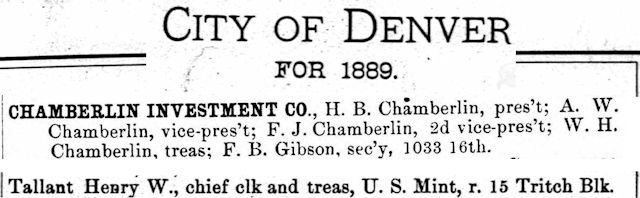

Chamberlin’s business partners were his brothers A. W., F. J., and W. H. Henry W. Tallant, treasurer of the Denver mint, would become manager of Chamberlin’s Fort Worth dealings.

Chamberlin’s business partners were his brothers A. W., F. J., and W. H. Henry W. Tallant, treasurer of the Denver mint, would become manager of Chamberlin’s Fort Worth dealings.

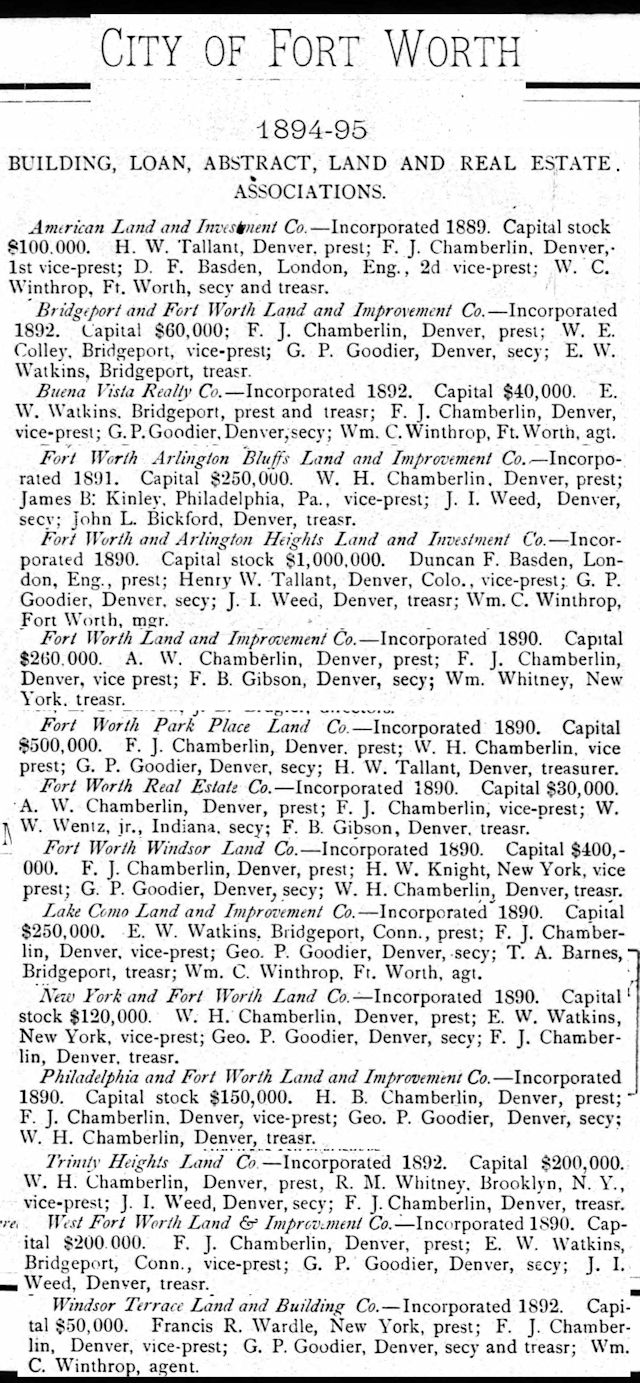

Beginning in 1889 Chamberlin and his brothers, along with Tallant, hit Cowtown like a Rocky Mountain mafia and soon were wheeling and dealing. The 1894 city directory lists the local “land companies” in which the Chamberlins and/or Tallant were officers. Other Chamberlin interests not included here are the Arlington Heights water, streetcar, and electric companies.

Beginning in 1889 Chamberlin and his brothers, along with Tallant, hit Cowtown like a Rocky Mountain mafia and soon were wheeling and dealing. The 1894 city directory lists the local “land companies” in which the Chamberlins and/or Tallant were officers. Other Chamberlin interests not included here are the Arlington Heights water, streetcar, and electric companies.

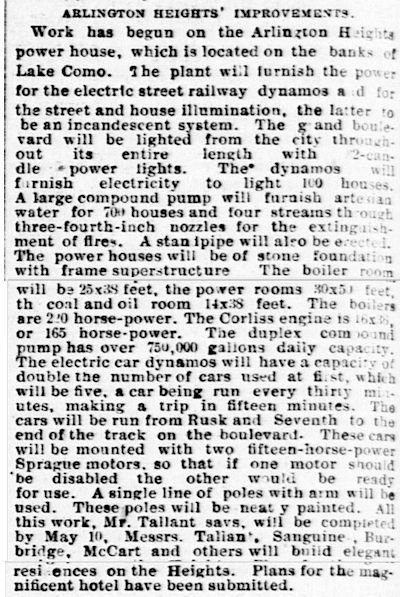

On March 14, 1890 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that work had begun on the powerhouse at Chamberlin’s Lake Como to provide electricity for his Arlington Heights streetcar line, streetlights, and the homes to be built.

On March 14, 1890 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that work had begun on the powerhouse at Chamberlin’s Lake Como to provide electricity for his Arlington Heights streetcar line, streetlights, and the homes to be built.

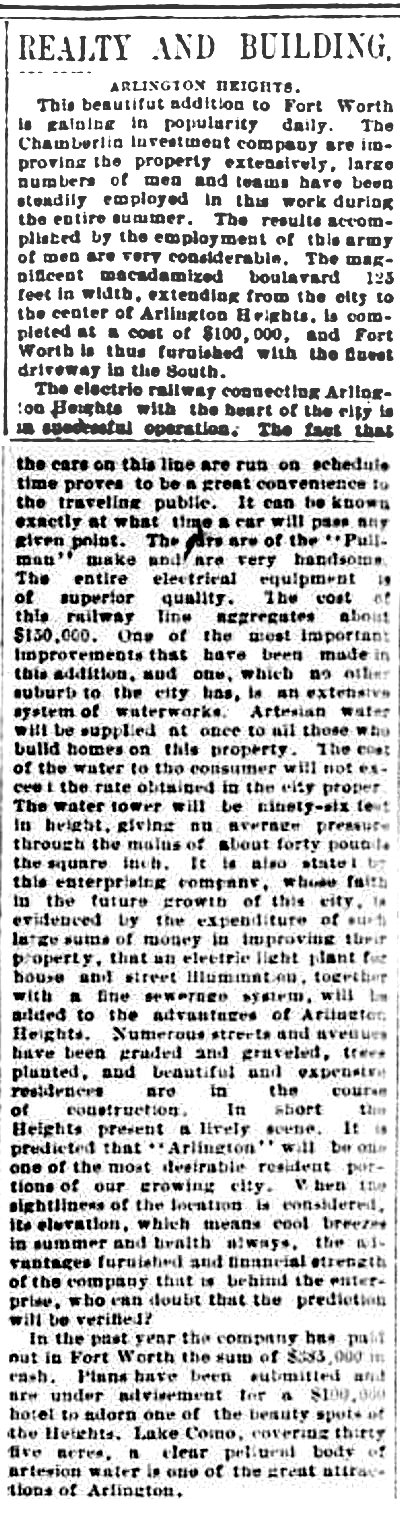

By September 25, 1890 the Gazette reported more progress at Arlington Heights and Lake Como. Chamberlin built a “magnificent macadamized boulevard” to Fort Worth (originally the Weatherford Road, later Arlington Heights Boulevard, then Camp Bowie Boulevard). He had impounded thirty-five-acre Lake Como, fed by “clear pellucid body of artesian water.” At the lake he had built the powerhouse plant to provide electricity. And the lofty (ahem) “elevation” of Arlington Heights would assure “cool breezes in summer.”

By September 25, 1890 the Gazette reported more progress at Arlington Heights and Lake Como. Chamberlin built a “magnificent macadamized boulevard” to Fort Worth (originally the Weatherford Road, later Arlington Heights Boulevard, then Camp Bowie Boulevard). He had impounded thirty-five-acre Lake Como, fed by “clear pellucid body of artesian water.” At the lake he had built the powerhouse plant to provide electricity. And the lofty (ahem) “elevation” of Arlington Heights would assure “cool breezes in summer.”

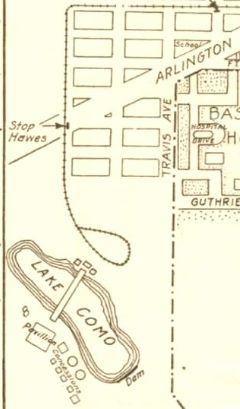

This Sanborn map of 1893 shows the powerhouse beside Lake Como.

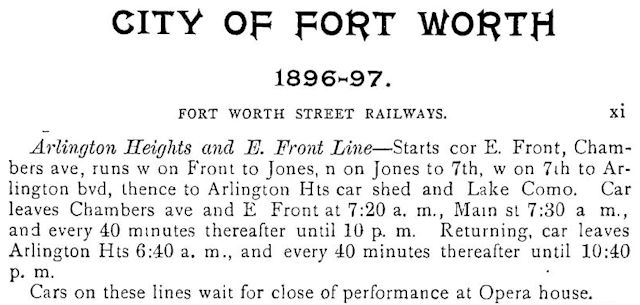

In 1896 the Arlington Heights streetcar line ran from East Front (Lancaster today) downtown north to Jones Street, west on 7th Street to Arlington Heights Boulevard and on to Lake Como.

In 1896 the Arlington Heights streetcar line ran from East Front (Lancaster today) downtown north to Jones Street, west on 7th Street to Arlington Heights Boulevard and on to Lake Como.

“Nature gave Texas Arlington Heights”: In that same edition the Gazette featured this ad promoting Chamberlin’s Arlington Heights as “the most desirable place of residence in Texas.” The ad includes images of the powerhouse and of one of the fine residences.

“Nature gave Texas Arlington Heights”: In that same edition the Gazette featured this ad promoting Chamberlin’s Arlington Heights as “the most desirable place of residence in Texas.” The ad includes images of the powerhouse and of one of the fine residences.

Chamberlin hired Fort Worth’s uberarchitect, Marshall Sanguinet, to design for Arlington Heights a grand hotel (Ye Arlington Inn) and some model houses. (Image of Ye Arlington Inn from Photographs of Fort Worth by D. H. Swartz.)

Chamberlin hired Fort Worth’s uberarchitect, Marshall Sanguinet, to design for Arlington Heights a grand hotel (Ye Arlington Inn) and some model houses. (Image of Ye Arlington Inn from Photographs of Fort Worth by D. H. Swartz.)

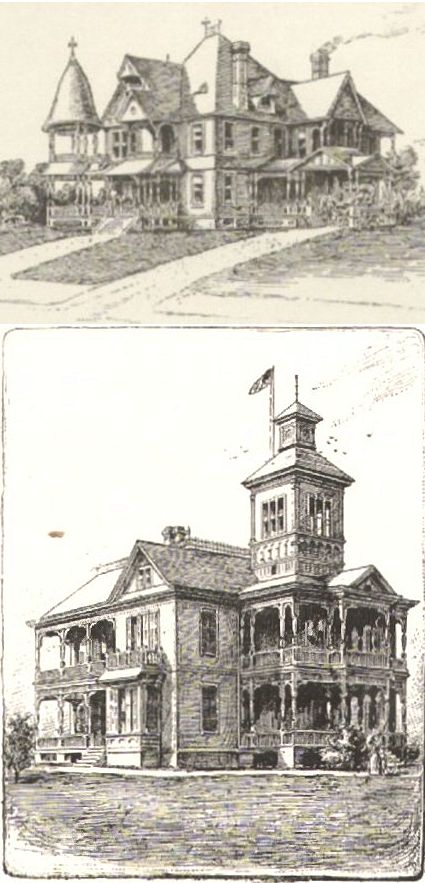

Two Arlington Heights homes in 1891. The top house was that of Henry W. Tallant and later Robert McCart (another Chamberlin associate) on Bryce Avenue. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Two Arlington Heights homes in 1891. The top house was that of Henry W. Tallant and later Robert McCart (another Chamberlin associate) on Bryce Avenue. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

The Tallant-McCart house survived well into the twentieth century. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

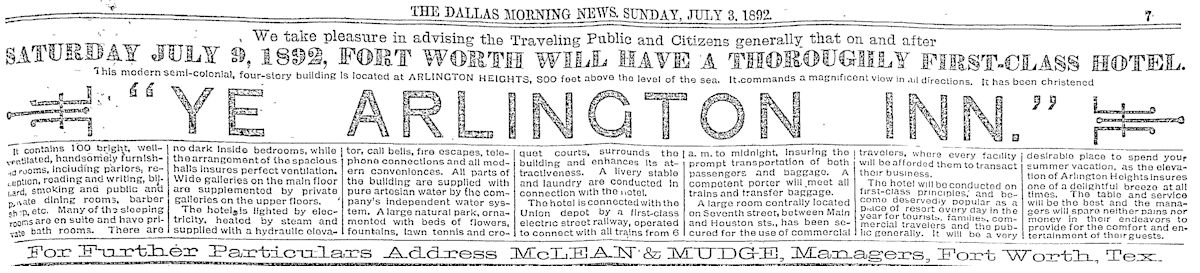

On July 3, 1892 the Dallas Morning News ran this ad proclaiming the Ye Arlington Inn, with electric lighting, steam heat, hydraulic elevator, telephone connections, and en suite bathrooms, to be “a thoroughly first-class hotel.” The inn was located at today’s Merrick Street and Crestline Road.

On July 3, 1892 the Dallas Morning News ran this ad proclaiming the Ye Arlington Inn, with electric lighting, steam heat, hydraulic elevator, telephone connections, and en suite bathrooms, to be “a thoroughly first-class hotel.” The inn was located at today’s Merrick Street and Crestline Road.

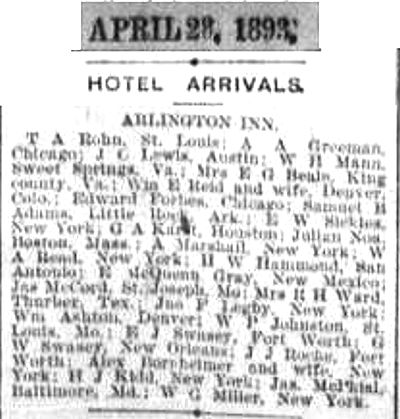

People from all over the country stayed at Ye Arlington Inn.

People from all over the country stayed at Ye Arlington Inn.

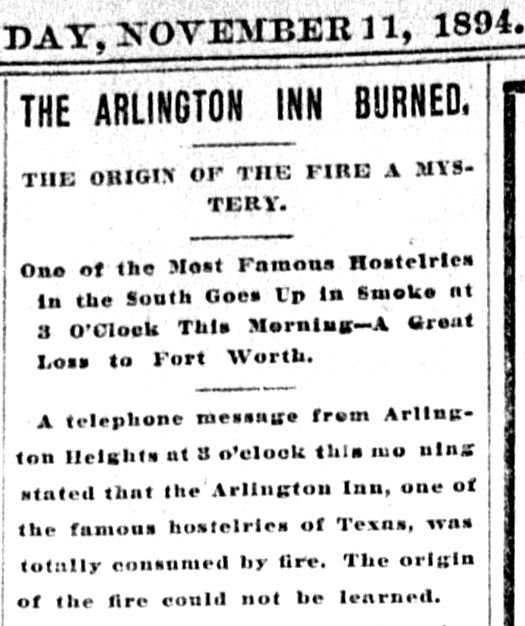

But the years 1893-1894 hit Chamberlin with a double whammy: The national silver panic of 1893 battered his finances; on November 11, 1894 the Gazette reported that his Ye Arlington Inn had burned.

But the years 1893-1894 hit Chamberlin with a double whammy: The national silver panic of 1893 battered his finances; on November 11, 1894 the Gazette reported that his Ye Arlington Inn had burned.

This 1895 map shows Lake Como, the powerhouse, Ye Arlington Inn (“Burnt”). Note the “Stove Works” to the east. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

This 1895 map shows Lake Como, the powerhouse, Ye Arlington Inn (“Burnt”). Note the “Stove Works” to the east. (From Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Development of Arlington Heights and Lake Como trolley park was slowed for a few years. During that time the lake provided little more than fishing and boating. In 1897 Chamberlin was killed while bicycling in London.

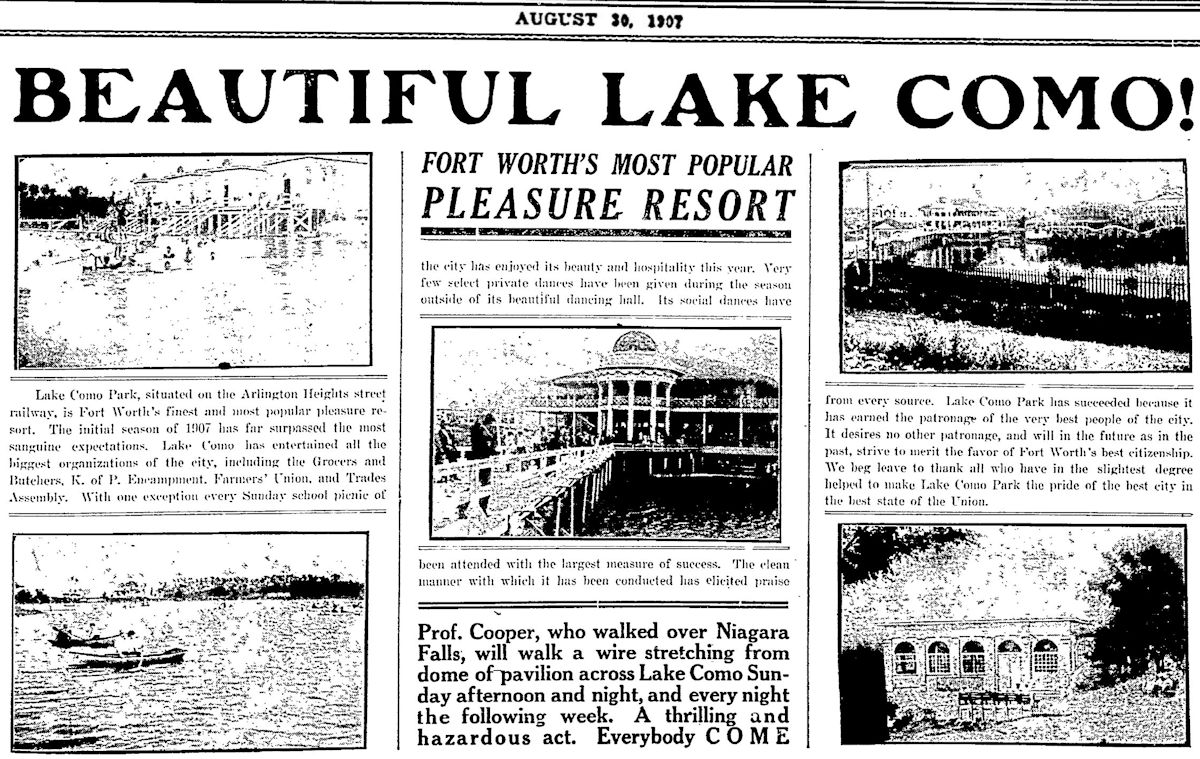

But new owners bought the Lake Como park, and by early in the new century Lake Como had fulfilled Chamberlin’s promise. The park had a grand pavilion on the water, a boardwalk, a merry-go-round, a Ferris wheel, gazebos, a boathouse, a shooting gallery, rowboats, and naphtha launches (boats propelled by a motor that ran on naphtha vapors).

Streetcars ran every forty minutes from downtown to the lake. Fare was a nickel.

This Telegram ad in 1905 told the world that after a few years of stagnation “beautiful Arlington Heights” was booming, and Lake Como was “smiling.” And what’s not to smile about “where nature has been lavish with her gifts”? Improved “electric road.” More fine houses in “the most fashionable suburb in Fort Worth, if not in all Texas.” A new country club. (In the lower left, Fairview—the house and carriage house of Mayor William Bryce—still stands on the street named for him.)

Lake Como was advertised as “the cool spot,” with its “breezy skating rink” “where they all go,” the “most beautiful lake in the south.”

The lake hosted concerts, pageants, water carnivals, and fish bakes. Early in the 1900s popular actress and singer Lillian Russell visited the lake.

“Go where the crowd goes”: On May 9, 1908 the Telegram announced that “Niles and Hart, the monarchs of mirth,” and “Edwin Winchester, the musical monologist,” would entertain at Lake Como. Other attractions included a vaudeville bill, band concert, and figure-eight roller coaster.

“Go where the crowd goes”: On May 9, 1908 the Telegram announced that “Niles and Hart, the monarchs of mirth,” and “Edwin Winchester, the musical monologist,” would entertain at Lake Como. Other attractions included a vaudeville bill, band concert, and figure-eight roller coaster.

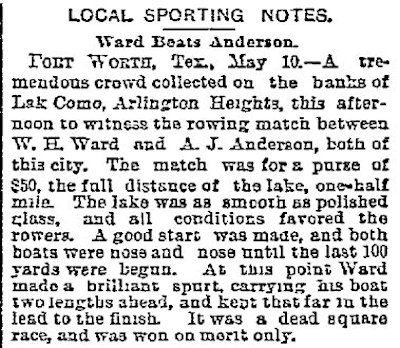

On May 11, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported a rowing contest on Lake Como between sporting goods dealer A. J. Anderson and William H. Ward, proprietor of the White Elephant Saloon.

On May 11, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported a rowing contest on Lake Como between sporting goods dealer A. J. Anderson and William H. Ward, proprietor of the White Elephant Saloon.

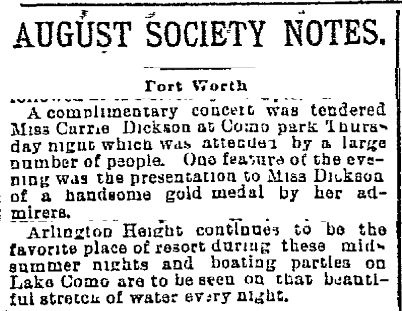

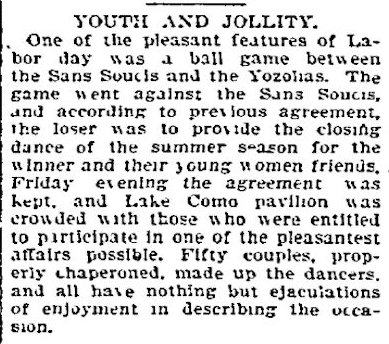

The society pages of the newspapers regularly mentioned Lake Como as the setting for moonlight picnics, boating parties, hayrides, watermelon parties, and dances for young socialites. Such events were usually chaperoned. This clip is from the August 24, 1891 Dallas Morning News. (In 1909 four merrymakers were injured in a “riot” at the lake during the Independence Day weekend.)

The society pages of the newspapers regularly mentioned Lake Como as the setting for moonlight picnics, boating parties, hayrides, watermelon parties, and dances for young socialites. Such events were usually chaperoned. This clip is from the August 24, 1891 Dallas Morning News. (In 1909 four merrymakers were injured in a “riot” at the lake during the Independence Day weekend.)

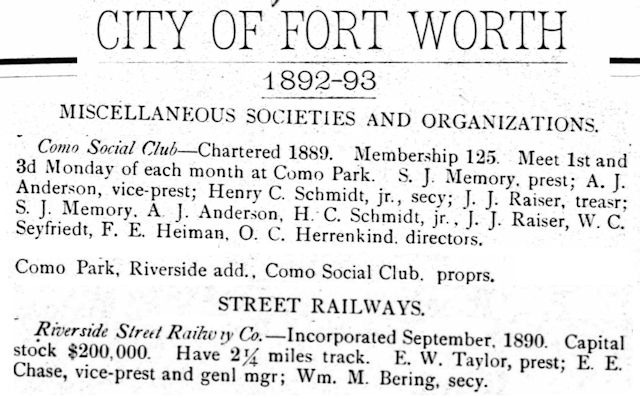

(To complicate matters, there was a Germanic Como Social Club that in the early 1890s hosted Maifest at a Como Park in Riverside east of town at the terminus of the short-lived Riverside streetcar line. E. E. Chase was vice president of the streetcar company.)

On September 15, 1901 the Telegram reported on a chaperoned dance at Lake Como pavilion that was replete with “ejaculations of enjoyment.”

On September 15, 1901 the Telegram reported on a chaperoned dance at Lake Como pavilion that was replete with “ejaculations of enjoyment.”

In 1907 Lake Como boasted of having earned “the patronage of the very best people of the city” and reminded those folks that Professor Cooper, who had walked over Niagara Falls on a wire, would perform a similar feat over Lake Como.

In 1907 Lake Como boasted of having earned “the patronage of the very best people of the city” and reminded those folks that Professor Cooper, who had walked over Niagara Falls on a wire, would perform a similar feat over Lake Como.

This map shows the streetcar loop, boardwalk, and pavilion, among other structures.

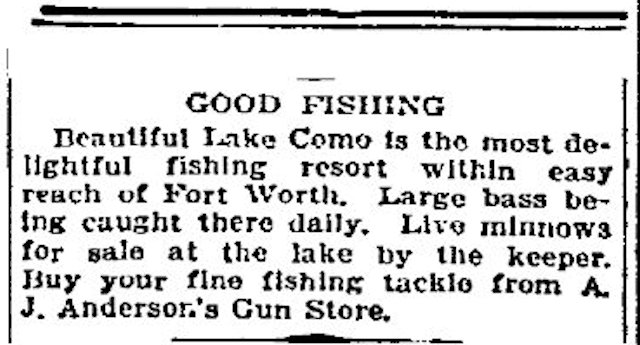

Even with all the added attractions, in the new century Lake Como continued to be a favorite fishing hole. This ad by A. J. Anderson is from the May 11, 1908 Telegram.

Even with all the added attractions, in the new century Lake Como continued to be a favorite fishing hole. This ad by A. J. Anderson is from the May 11, 1908 Telegram.

In 1910 W. C. Stripling Department Store held its first company picnic at Lake Como. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In 1910 W. C. Stripling Department Store held its first company picnic at Lake Como. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

But the new century that had begun so favorably for Lake Como dealt the park one blow after another.

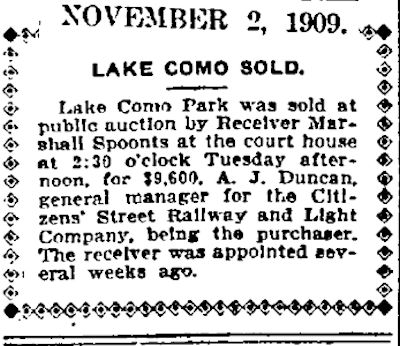

In 1909 the park was sold in receivership for $9,600 ($265,000 today).

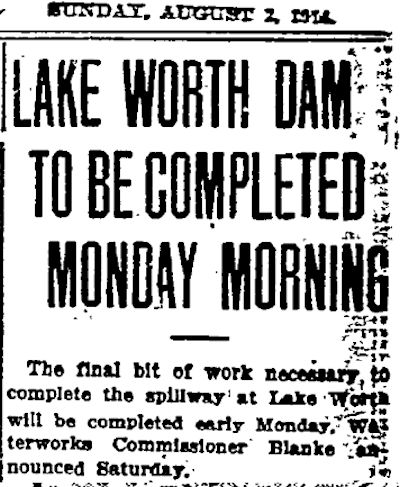

And in 1914 the city of Fort Worth dammed the Trinity River to build Lake Worth. The new lake, with its competing amenities, rendered Lake Como less popular.

And in 1914 the city of Fort Worth dammed the Trinity River to build Lake Worth. The new lake, with its competing amenities, rendered Lake Como less popular.

In 1915 the park still offered boating, bathing, dancing, skating, and special attractions such as an “exhibition of deep sea diving.” But the park stopped advertising in the newspaper in 1917. In 1918 Army engineers of Camp Bowie used the lake for pontoon training. By 1922 the resort was mentioned often in the Star-Telegram’s “Remember When” nostalgia column.

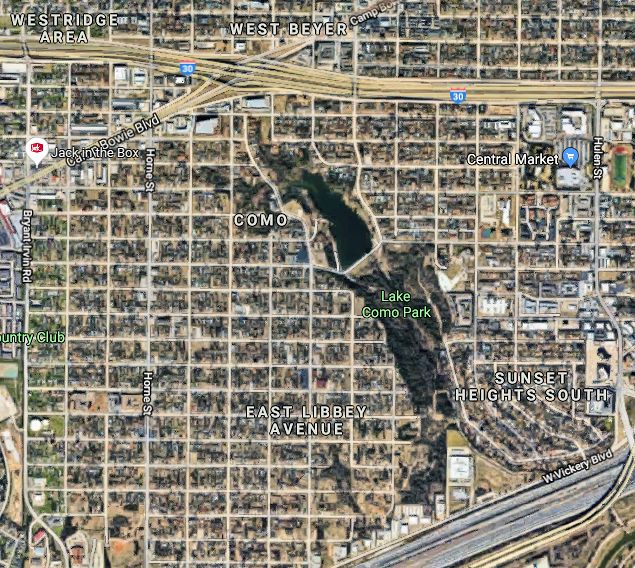

Today, of the Gay Nineties trolley park “where the crowd goes” only the lake survives.

Today, of the Gay Nineties trolley park “where the crowd goes” only the lake survives.

Who owned the land Chamberlain purchased in 1897?

How did the civic leaders support/encourage this purchase?

Chamberlin bought most of his land in 1889. I am not aware that he bought any land in 1897, the year he died. He bought much of his land from Robert McCart. The post has a link to a two-part post on McCart and his extensive land dealings on the West Side.

By the middle 1960s Como was synonymous with a segregated black neighborhood and its segregated all-black Como High School. Homes in the area were small, but neat and tidy. Great bar-b-que was served at a couple of restaurants on its main drag. There was no history of crime or gang activity. In 1968 six black former Como High students were integrated into the formerly all-white Arlington Heights High School. That was my senior year there. I recall the six of them often walked the campus together. None of them were in any of my classes, and I didn’t get to know any of the group. I saw no anger or resentment at the integration, which everyone knew would quickly increase because the decrepit Como High was scheduled for demolition. Some twenty years later, when my nephew was the starting catcher for the State Champion Arlington Heights baseball team, the school population identified as somewhere around 40% white, 40% black, and the rest hispanic or other race.

“Ejaculations of enjoyment,” eh? I thought they were property chaperoned….

It makes you wonder what tidbits of today’s journalism readers will be snickering at a century from now.