If you stand on the courthouse steps and call out the names of downtown’s north-south streets from right to left—excluding Main in the center—you are calling a roll of men from Texas and American history:

Burnet—David Gouverneur Burnet, New Jersey-born, was an empresario (agent authorized by the Mexican government to colonize Texas), lawyer, and politician. He was interim president of the Republic of Texas (1836) and vice president (1838-1841). (Contrary to the spelling on our street signs and maps, the street was named for David one-t Burnet, not cattleman Samuel Burk two-ts Burnett, who donated land for the adjacent Burnett Park.)

Lamar—Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar was the second president of the republic.

Taylor—Zachary Taylor was twelfth president of the United States.

Monroe—James Monroe was fifth president of the United States.

Jennings—Thomas Jefferson Jennings was a Texas attorney general, husband of Sarah Gray Jennings, and father of Hyde Jennings. He died in Fort Worth in 1881.

Throckmorton—James Webb Throckmorton was twelfth governor of Texas.

Houston—Sam Houston was the Lone Star State’s Uncle Sam: the hero of San Jacinto, first and third president of the republic, and seventh governor of the state.

Commerce—

Calhoun—John C. Calhoun was U.S. secretary of war, a U.S. senator, and seventh vice president of the United States.

Jones—Anson Jones was the fourth and final president of the republic. A physician, he was born in Massachusetts and came to—whoa. Back up two streets. Commerce? What kind of name is that for a historic personage?

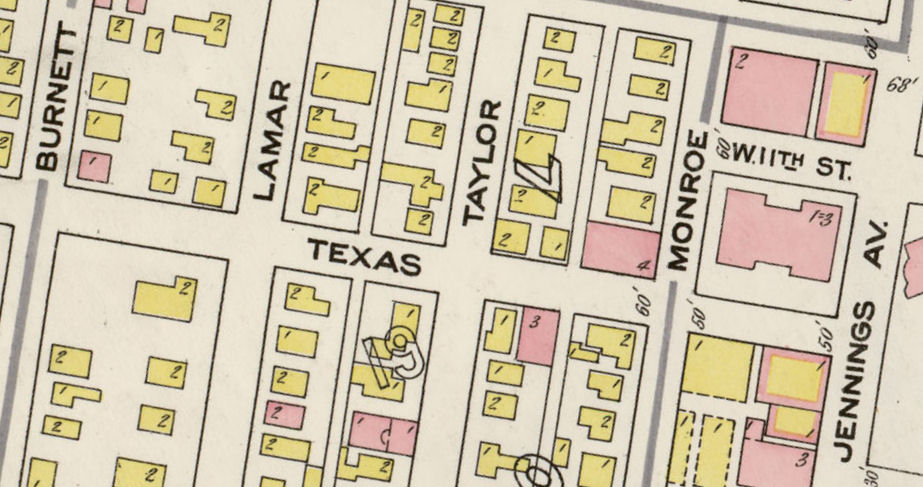

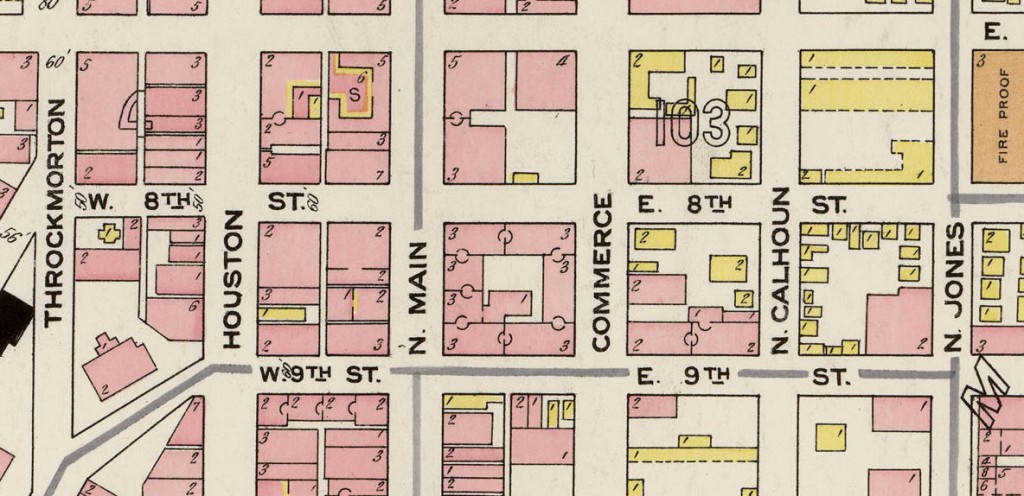

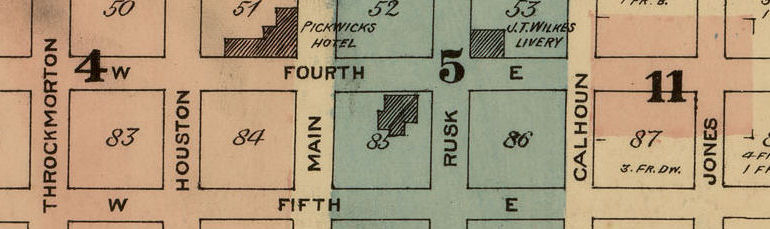

Ah, but it was not always so. Commerce Street, as this 1885 Sanborn map shows, originally was named “Rusk.”

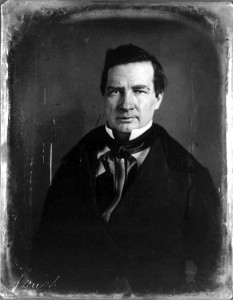

Thomas Jefferson Rusk (1803-1857), born in South Carolina, signed the Texas declaration of independence, was a general at the Battle of San Jacinto. He was commander-in-chief of the republic’s army, the republic’s first secretary of war, chief justice of the republic’s supreme court, later a U.S. senator from Texas, and president pro tem of the U.S. Senate in 1857. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Thomas Jefferson Rusk (1803-1857), born in South Carolina, signed the Texas declaration of independence, was a general at the Battle of San Jacinto. He was commander-in-chief of the republic’s army, the republic’s first secretary of war, chief justice of the republic’s supreme court, later a U.S. senator from Texas, and president pro tem of the U.S. Senate in 1857. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

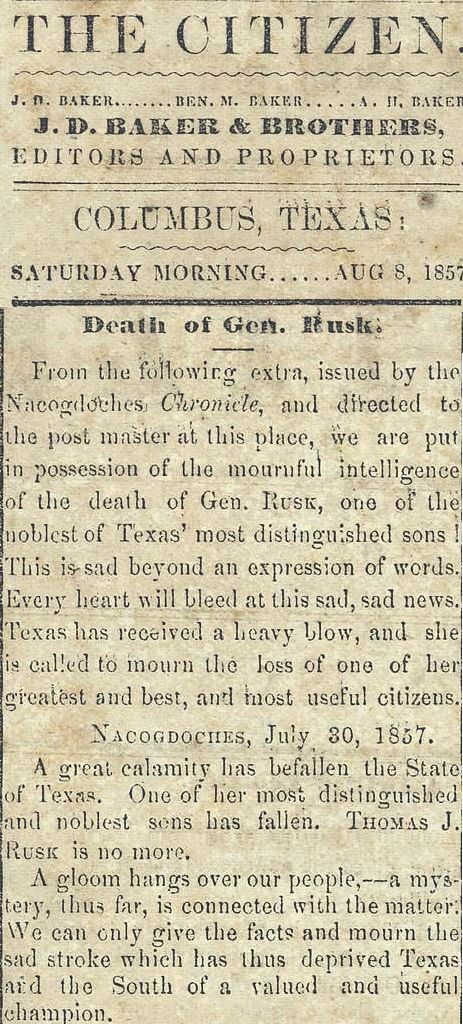

When Rusk died in 1857 he was eulogized as one of Texas’s “most distinguished and noblest sons.”

When Rusk died in 1857 he was eulogized as one of Texas’s “most distinguished and noblest sons.”

Fast-forward fifty-two years. In October 1909 Fort Worth property owners on Rusk Street petitioned for a street name change but gave no reason for the request. Rusk Street had long been the black heart of Hell’s Half Acre. Between 1892 and 1909 at least three police officers were shot to death in just a two-block stretch of Rusk Street. Clip is from the October 11 Star-Telegram.

Fast-forward fifty-two years. In October 1909 Fort Worth property owners on Rusk Street petitioned for a street name change but gave no reason for the request. Rusk Street had long been the black heart of Hell’s Half Acre. Between 1892 and 1909 at least three police officers were shot to death in just a two-block stretch of Rusk Street. Clip is from the October 11 Star-Telegram.

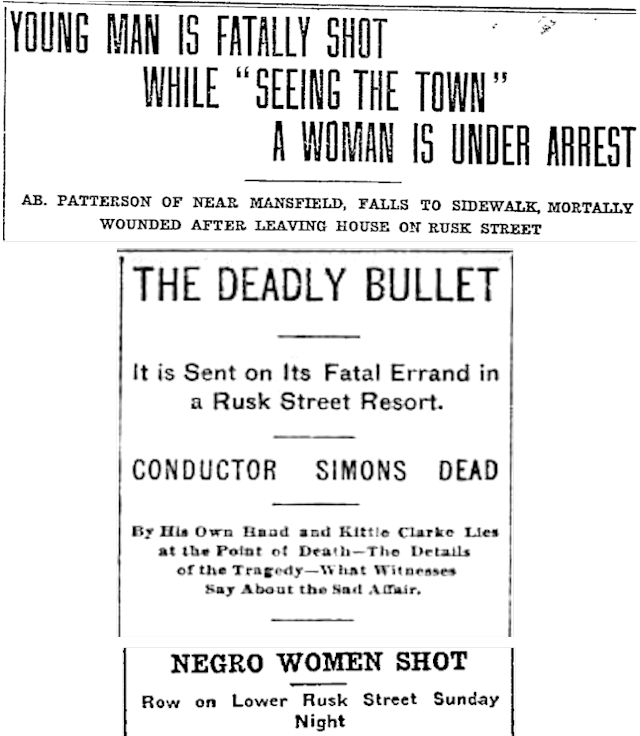

Rusk Street often made the headlines in crime news.

Rusk Street often made the headlines in crime news.

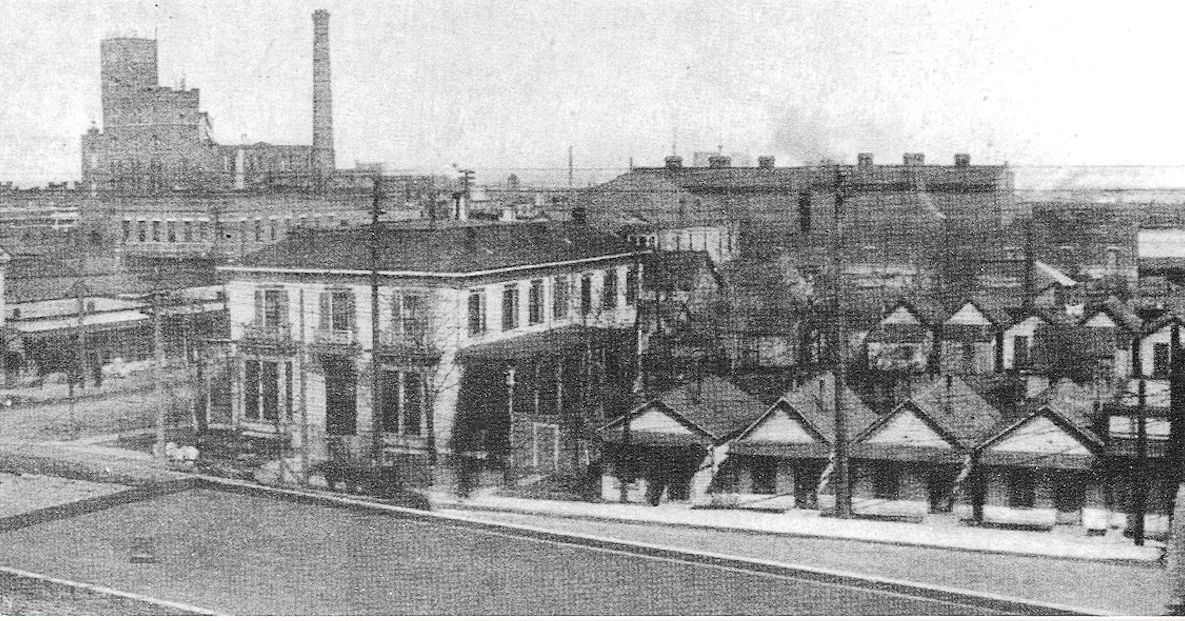

Rusk Street below about 9th Street was a warren of saloons, gambling houses, and brothels and cribs, which were one-room shacks where “crib girls” (prostitutes) worked. This photo of 1906 shows the 1200 block with a brothel at 1201 and a row of cribs. Texas Brewing Company can be seen in the background on Jones Street. (Photo from Dallas Historical Society.)

Rusk Street below about 9th Street was a warren of saloons, gambling houses, and brothels and cribs, which were one-room shacks where “crib girls” (prostitutes) worked. This photo of 1906 shows the 1200 block with a brothel at 1201 and a row of cribs. Texas Brewing Company can be seen in the background on Jones Street. (Photo from Dallas Historical Society.)

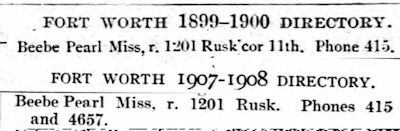

The madam of the brothel at 1201 Rusk was Pearl Beebee.

The madam of the brothel at 1201 Rusk was Pearl Beebee.

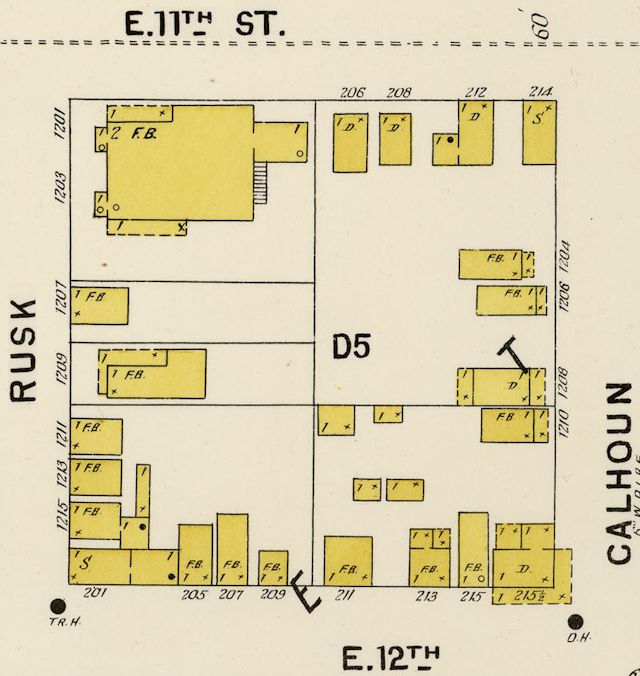

The Sanborn map shows the 1200 block of Rusk in 1898. The house at 1201 and the cribs are labeled “F.B.” (“female boarding,” a euphemism for “brothel”).

The Sanborn map shows the 1200 block of Rusk in 1898. The house at 1201 and the cribs are labeled “F.B.” (“female boarding,” a euphemism for “brothel”).

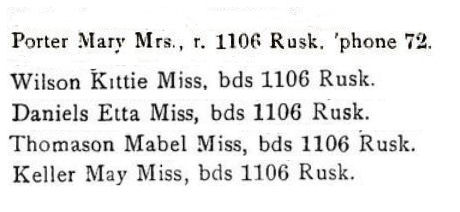

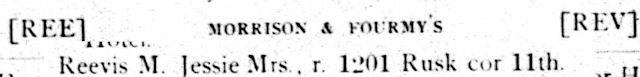

Madam Mary Porter kept a female boarding house one block north of Pearl Beebe at 1106 Rusk Street. The 1899 city directory lists some of her boarders.

Madam Mary Porter kept a female boarding house one block north of Pearl Beebe at 1106 Rusk Street. The 1899 city directory lists some of her boarders.

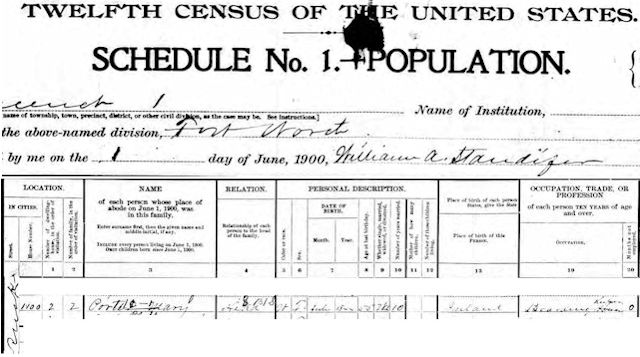

One year later Mary Porter listed her occupation as “boarding house keeper” at 1100 Rusk.

One year later Mary Porter listed her occupation as “boarding house keeper” at 1100 Rusk.

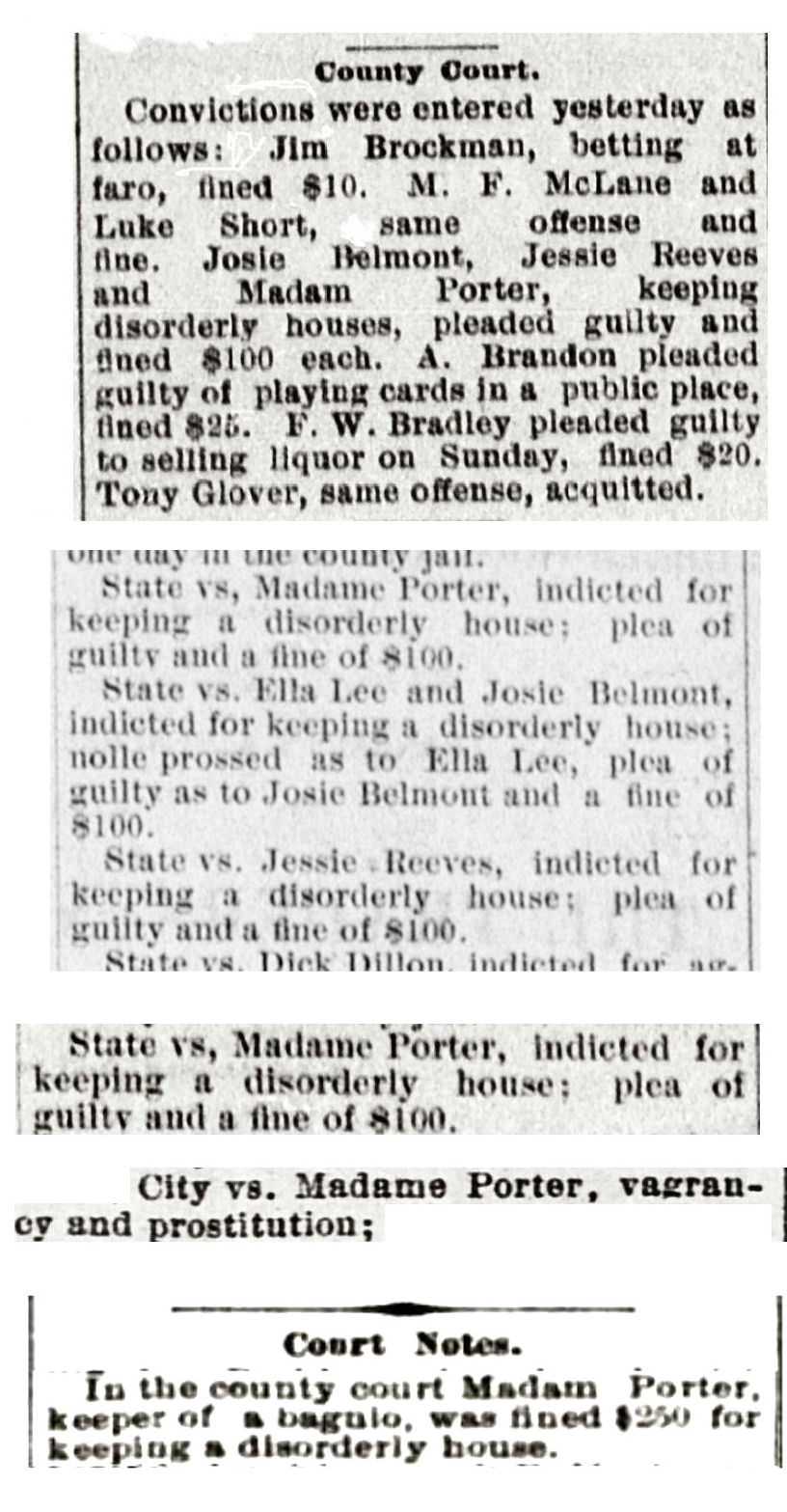

As the newspaper crime briefs show, Mary Porter was one of the busiest businesswomen on Rusk Street during the 1890s. Other Rusk Street madams who often faced fines were Josie Belmont and Jessie Reeves. Disorderly house and bagnio are synonyms for brothel.

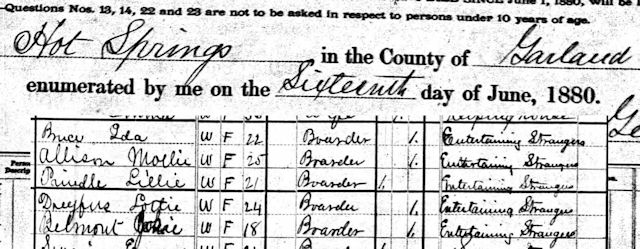

In 1880 Josie Belmont had been a “boarder” in Hot Springs, where she listed her occupation as “entertaining strangers.” She was eighteen, listed as widowed.

In 1880 Josie Belmont had been a “boarder” in Hot Springs, where she listed her occupation as “entertaining strangers.” She was eighteen, listed as widowed.

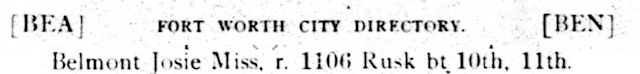

By 1888 Josie was entertaining strangers in Fort Worth. She lived at 1106 Rusk, the brothel of Mary Porter.

By 1888 Josie was entertaining strangers in Fort Worth. She lived at 1106 Rusk, the brothel of Mary Porter.

Likewise, Jessie Reeves, listed in the 1888 city directory as “Jessie M. Reevis,” lived at 1201 Rusk, the brothel of Pearl Beebe.

Likewise, Jessie Reeves, listed in the 1888 city directory as “Jessie M. Reevis,” lived at 1201 Rusk, the brothel of Pearl Beebe.

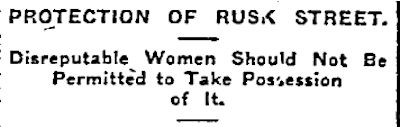

This headline from 1902 seems to ignore the fact that a business transaction requires both a seller and a buyer.

This headline from 1902 seems to ignore the fact that a business transaction requires both a seller and a buyer.

(Mary Porter and at least three prostitutes are buried in a multigrave plot owned by Pearl Beebe at Oakwood Cemetery. The plot is known as “Soiled Doves Row.”)

One account of Fort Worth history says the name of Rusk the street was changed to stop besmirching the hallowed name of Rusk the man. But might the petitioning merchants on that street have had a more pragmatic motive? Changing the name of the street would remove the stigma of a Rusk Street address and allow merchants a fresh start: They would get a new address without having to move.

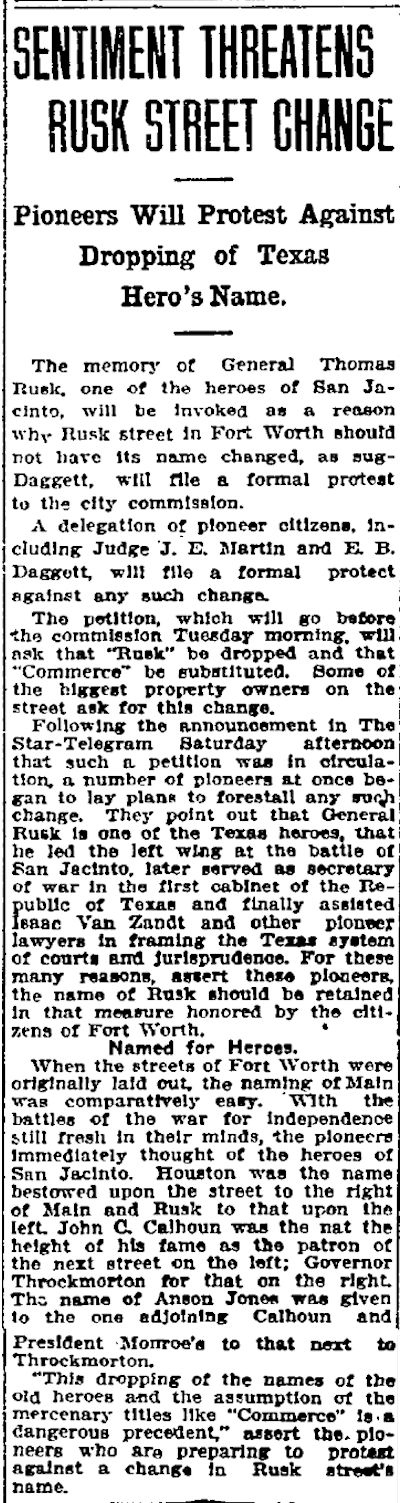

On December 12 the Star-Telegram reported that oldtimers, including E. B. Daggett, opposed the proposed street name change.

On December 12 the Star-Telegram reported that oldtimers, including E. B. Daggett, opposed the proposed street name change.

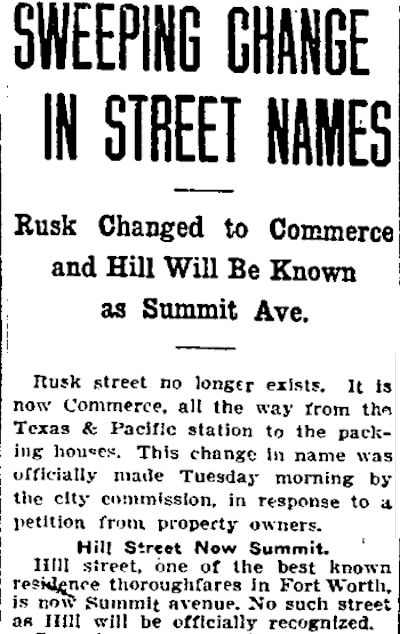

But two days later, on December 14, 1909, as this Star-Telegram clip shows, Rusk Street from the T&P station north was renamed “Commerce.” (In 1903 Rusk Street from the T&P station south had been renamed “Bryan” for William Jennings Bryan.) Several other street names were changed in 1909. For example, Hill Street through Quality Hill became “Summit Avenue.”

But two days later, on December 14, 1909, as this Star-Telegram clip shows, Rusk Street from the T&P station north was renamed “Commerce.” (In 1903 Rusk Street from the T&P station south had been renamed “Bryan” for William Jennings Bryan.) Several other street names were changed in 1909. For example, Hill Street through Quality Hill became “Summit Avenue.”

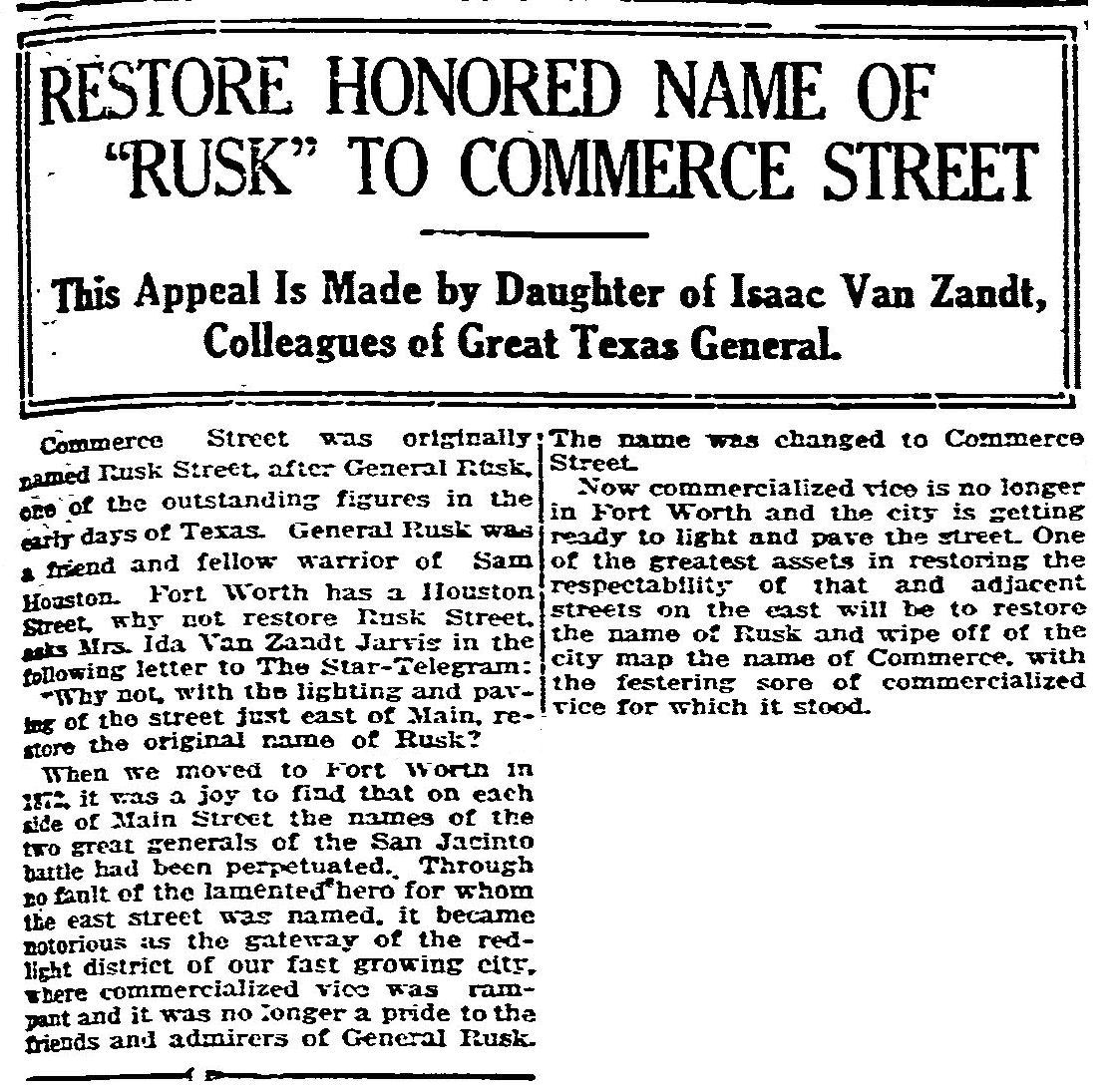

Fast-forward to 1920. Ida Van Zandt Jarvis asked that the Rusk name be restored. Ida Van Zandt Jarvis was daughter of Isaac Van Zandt, who was instrumental in the annexation of Texas in 1845, sister of Fort Worth civic leader K. M. Van Zandt, and wife of civic leader James Jones Jarvis. Her letter to the editor alludes to the theory that the name of Rusk the street had been changed to avoid dishonoring Rusk the man.

(Note that not until 1920 was Commerce Street paved and lighted.)

Others echoed the appeal of Mrs. Van Zandt Jarvis. Rusk lived and died in Nacogdoches. (Randolph Clark and brother Addison in 1873 founded the college that became TCU.)

Their appeals went unheeded. Getting Commerce Street renamed “Rusk Street” now is even less likely to happen than is getting the correct “Burnet” spelling applied to street signs and maps.

Bonus trivia: In South Carolina, Thomas Jefferson Rusk’s family once rented land from the guy one street over: John C. Calhoun. And Rusk later had a land grant in the Texas colony of . . . David G. one-t Burnet.

More bonus trivia: Presidents Taylor and Monroe were cousins of Sarah Gray Jennings, wife of the guy one street over: Thomas Jefferson Jennings.

Dear Mike Nichols,

I’ve enjoyed your Hometown by Handlebar from afar — well, from Spur, Texas — since the start of my researches into 1876, and now 1894, Fort Worth. The Star-Telegram stable certainly has produced some excellent chroniclers of the city’s history and culture over the years, but your blog is everything a reader could want: story, photos, clippings, and most of all, maps.

Keep the great working coming.

Barbara Brannon, aka Will Brandon, author of THE WOLF HUNT: A TALE OF THE TEXAS BADLANDS

Thank you for visiting this site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, has passed away and we are working on a solution on how best to preserve it.

When did Burnet Street become Burnett Street ?

Billy Joe, the street appeared as “Burnett” in the 1877 city directory-long before Samuel Burk Burnett was prominent or gave Fort Worth a park. Both spellings appeared in some city directories. I don’t know when “Burnett” appeared on street signs. Quentin McGown told me he is of the opinion it should be “Burnet.”

I just discovered that my paternal grandfather’s parents ran a boarding house and a grocery store in 1894 on the corner of S. Rusk and E. Daggett (124 S. Rusk). By 1900, he sold and moved to Wise County. Thanks to you, I, also, discovered S. Rusk had been renamed to Bryan.

That was just one block from the T&P roundhouse. Your great-grandparents probably did a lot of business with railroad families.