It was pure Hollywood, the stuff of Jimmy Stewart, Van Johnson, Robert Mitchum: Fearless, nonchalant test pilot lands crippled bomber as if it’s just another day at the office.

In 1947 Fort Worth’s bomber plant—Convair—was under Army contract to build a new strategic bomber: the B-36 Peacemaker. The vital statistics of the B-36 were boggling: 410,000 pounds maximum takeoff weight, six 3,000-horsepower engines, wing span of 230 feet, tires nine feet in diameter. Why, just the inner tube of a B-36 tire weighed eight hundred pounds.

The cost of the XB-36 prototype, the first B-36 built, was equally boggling: $20 million ($209 million today).

B-36 video from KERA (no audio):

The B-36 dwarfed a B-29. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The B-36 dwarfed a B-29. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

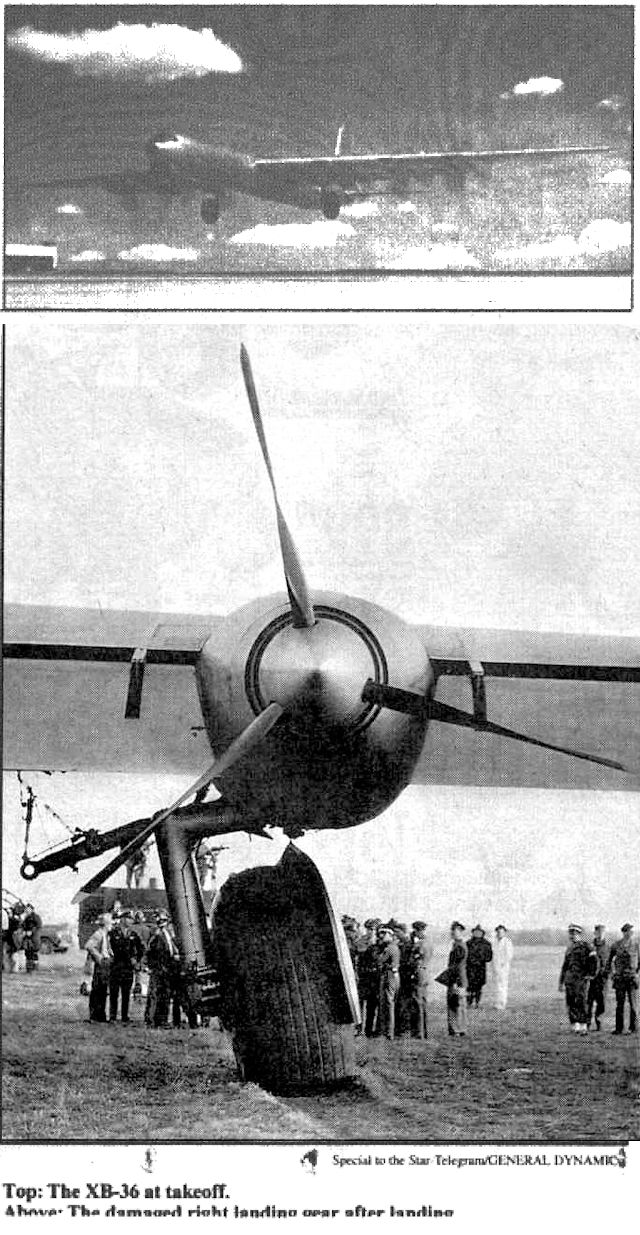

On March 26 Convair’s XB-36 took off from adjacent Fort Worth Army Air Field (renamed “Carswell Air Force Base” in 1948) on its sixteenth test flight.

It would not be a milk run.

Photos from the March 28 Star-Telegram.

Photos from the March 28 Star-Telegram.

“We took off routinely enough around noon that day,” civilian test pilot Beryl A. Erickson, then thirty years old, remembered years later, “and at seven hundred feet altitude south of Fort Worth Army Air Field [co-pilot] Gus Green raised the landing gear, and the plane just went insane.

“There were sounds of rending metal under unbelievable stress violently shrieking and rupturing. I thought that from the sounds and the way the plane was acting that we had suffered a mid-air collision.”

In reality, as the plane’s landing gears were pivoting into their wells under the plane, the retracting hydraulic strut cylinder of the right wing landing gear had exploded. The heavy landing gear and wheel fell into the down position, limp. An adjacent engine housing was smashed, and hydraulic, oil, and fuel lines ruptured.

Fire broke out, but the flight engineer quickly crawled into the wing and extinguished the flames.

Erickson recalled later that he had been confident that he and co-pilot Green could still land the damaged plane even though they would have no brakes and no nose wheel steering because of the damaged hydraulics.

“The main threat,” Erickson said, “was that the main gear would collapse and allow the right wing to hit the ground and tear off, igniting the 21,000 gallons of highly volatile aviation gasoline aboard and burning us all up.”

The plane had no way to dump all that fuel, so Erickson had to burn it, flying in wide loops over the airfield. For six hours. (The B-36 was designed to fly a long way: ten thousand miles between stops at the gas pump.)

As Erickson began flying in loops, he ordered the twelve crewmen to bail out. As the men jumped, the bomber plant, airfield control tower, and ambulance drivers were networked by radio and telephone so that the ambulances could pick up the parachutists.

With each loop that Erickson flew, two crew members bailed out.

Army Air Corps Major Stephen P. Dillon jumped first so he could get back to the airfield as fast as possible to get to a vantage point where he could radio steering directions to Erickson after the XB-36 touched down.

Before the last man jumped Erickson manually cranked down the nose landing gear.

As the men jumped, the wind was blowing at thirty to thirty-five miles per hour, making their jumps trickier.

“I couldn’t maneuver the parachute like I should have,” recalled one crewman. “The wind was too strong.”

Nine of the twelve jumpers were injured. Injuries ranged from sprained ankles to broken bones and punctured lungs.

And then there were only three left in the sky: Erickson, Green, and the crippled Peacemaker.

Soldiers stood on the roofs of buildings on the airfield to watch the drama in the sky. On the ground, news spread by telephone and by radio broadcasts. Cars lined the perimeter of the airfield as people parked to watch Erickson fly his loops six thousand feet in the sky.

As Erickson and Green burned fuel, the two men planned how best to land the plane with the controls still at their command—rudder, aileron, the power of five usable engines—to compensate for the incapacitated right-wing landing gear. Erickson would try to keep the plane’s weight off the right landing gear because it might collapse and put the right wing on the ground. Remember: Erickson would have no brakes and no nose wheel steering.

At 6:15 p.m. ambulances and fire trucks lined the main airfield runway as the plane came in slowly at full flaps.

Major Dillon, who had been the first crewman to jump from the plane, had sprained an ankle when he hit the ground, but he was in the cockpit of a C-47 at the airfield, his radio tuned to the XB-36’s frequency when Erickson brought the plane down.

Erickson put the good left wheel on the runway first with a screech and a black puff of rubber. He kept the weight of the plane on the left wheel as long as he could and then eased the failed right wheel down as gently as one can when that wheel has to share the weight of 139 tons of hurtling metal. The right wing sagged lower than the left but never touched the runway.

The landing gear held.

Erickson recalled, “We landed with all wheels down just a little to the left of the center line of the runway, and soon Dillon was on the radio, telling us how to steer. We rolled to the end of the runway and edged off onto the soft earth at the left and stopped, but the right main gear held and the wing never touched the ground. That was fortunate because we still had eight thousand gallons of high octane aviation gas aboard.”

A crowd estimated in the tens of thousands cheered.

Pure Hollywood.

As the crippled plane had circled overhead, work on the B-36 program had continued in the bomber plant’s .9-mile-long assembly building. Then came an announcement on the building’s public address system: “The XB-36 has landed safely.”

Rather fractured headline is from the March 28 Star-Telegram.

Rather fractured headline is from the March 28 Star-Telegram.

Star-Telegram photo shows the damaged landing gear.

Star-Telegram photo shows the damaged landing gear.

Clip is from the March 27 Dallas Morning News.

Clip is from the March 27 Dallas Morning News.

The failure of the landing gear strut turned out to be a blessing for the B-36 program.

Erickson recalled that the bomber plant brass told him that the emergency landing saved the B-36 program, which had been in trouble because it was behind schedule, over budget, and under attack by the Navy, which wanted more carriers than bombers.

“It was all quite dramatic,” Erickson recalled. “The contract was in jeopardy, the plane was a year behind schedule, but the incident proved that although significantly damaged, the XB-36 could be safely landed, and two months later, with the new, redesigned landing gear retraction struts installed, it flew again.”

Convair president Harry Woodhead recalled that officials of Convair and the Army had anxiously watched the drama in the sky.

Those officials, Woodhead said, “realized that this was more than just another airplane in trouble. Production of B-36s is essential to America’s security, and the damage of the experimental model would have adversely affected both flight testing and production.”

In fact, the bomber plant would go on to produce 385 B-36s between 1947 and 1954. The bomber plant in 1947 employed eleven thousand workers.

Test pilots Erickson (who in 1956 would be the first pilot to fly Convair’s B-58 Hustler) and Green were back at the bomber plant early the next morning to watch the plane being repaired. Erickson downplayed his landing of the crippled behemoth: “It was just a plain, straight-forward job of earning shoes for the baby.”

Jimmy Stewart himself couldn’t have said it with more “Aw, shucks” humility.

Dillon was my uncle love the reference to kids shoes he had 11 children?! He retired as a test pilot for the Air Force and retired from McDonnell Douglas in Santa Monica CA. A very dynamic man thanks uncle Steve.

My Father was the radio man on that XB-36

March 1947. His name: John Medearis Hemby

he was 32.

Fun to read. And exciting. nice

Thanks. John Wayne could not have done it any better.

Super great, Mike. When I was young the B-36 was at GSW Airport. When we would visit I would climb up the landing gear to get inside. I could walk up right in the wing on the catwalk. Lots of birds lived inside. I had a small part in the restoration while I worked at GD. Better known as Generous Dynamics, they were true team players. Lockheed wanted anything to do with GD removed from the plant. So the B-36 had to go. I along with 35 thousand or so others were laid off. America believes she does not need us anymore, but one day she will know that she does. When the bands play, the flag waves, we will march forward, one nation, one people, one leader.

Thanks, Earl. That civilian earned his pay packet that day. It’s a shame that Fort Worth lost its B-36 and its steam locomotive. Even more amazing than the fact that the behemoth B-36 could get into the air is the fact that its almost-as-behemoth younger sibling, the B-52, got into the air—and stayed there. Still flying.

I can remember hearing them flying over Fort Worth. Every time one flew over, I would stop and watch it. I can still hear the roar of B-36 engines and prop noise from Carswell AFB as a boy attending Cub Scout meetings after school in the 1950’s on River Crest Drive. When the weather was just right, the sound carried for a very long ways! We have had many impressive military planes since the B-36, but never one that equaled the B-36.

God knows the Bomber plant provided a lot of shoes for my boys.

One wonders whether history might have played out differently had the B-36 crashed rather than the YB-49 Flying Wing which crashed at Muroc AFB in June with Glen Edwards aboard. It took decades for Nothrop to get by the B36 and the associated death of the Flying Wing.

That was a bad stretch for prototype aircraft. Have a post that includes the 1948 crash of the amazing Flying Wing at https://hometownbyhandlebar.com/?p=13586.