He traded fjords and lutefisk for prairies and beef and in the process became part of Fort Worth’s wild West lore.

Andre Jorgensen Anderson, born in Norway in 1855, sailed to America in 1873, arriving at Galveston (a voyage of 5,700 miles and at least two weeks).

After a year in Galveston, Anderson migrated north to Fort Worth, where in 1877 he opened a gun store in the 100 block of East Weatherford Street, near where the panther sleeps in front of the county administration building.

The 1880 census listed Anderson as a gunsmith.

Fast-forward to 1938. Anderson, by then eighty-three years old and living above his gun store at 1101 Houston Street, related his memories of early Fort Worth to an interviewer of the Federal Writers’ Project. Above is the abstract typed by the interviewer. Note that Anderson said his first big sale was $360 (about $8,000 today) in six-shooters and ammunition to the Sam Bass gang.

Anderson also told the interviewer about how he and two of his “six-gun Colt .45″s in 1884 played a role in Jim Courtright’s great escape (see Part 1). In his own words, here is Anderson’s account (which differs in some minor details from published accounts):

“When I established my gun store . . . I started with a capital of $15, borrowed money, and have continued in the business since. I am, at this time, the oldest merchandising business in Fort Worth.

“In Fort Worth in those days, the gun equalized the size of man, and everybody carried a gun. My business thrived. To illustrate how the pistol equalized man, I shall relate the Jim Courtright episode. Courtright was a man whom everyone admired. . . . He had served as marshal for the town and had an unusual large number of friends among all classes of people.” (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

“Courtright had gone to the territory of New Mexico and did duty as a mine guard. There was some labor trouble, and a clash resulted in some of the miners being killed. Courtright returned to Fort Worth after the affray and established a detective agency.

“One morning [October 18, 1884] a man called at Courtright’s office and discussed terms for Courtright’s service to apprehend some alleged criminal. Courtright was invited to accompany the caller to the Continental [Ginocchio] Hotel for the purpose of inspecting some papers the caller alleged he had. When the caller and he arrived in the hotel room, Courtright was disarmed by his caller and two men who were in the room. The three men were U.S. deputies from the marshal’s office in New Mexico. They placed Courtright under arrest on a charge of murder, which was supposed to have taken place during the labor trouble.

“[On the evening of October 19] [t]he deputies would not allow Courtright to communicate with anyone and were preparing to leave with him on the T&P 6:30 [8:55] p.m. westbound train. When his friends learned of his predicament, they organized a ways and means committee and did a good job of rescuing the man.

“Those days the largest restaurant in town was Lawson’s [Merchants’ Restaurant, operated by Christopher Lawson at 303 Main Street]. This restaurant was where officials always took prisoners for meals before entraining. The deputies, accompanied by six rangers, stopped at Lawson’s for supper. Lawson seated Courtright at the end of a table with the deputies and rangers on each side. The restaurant was crowded, all watching nonchalantly the officers and their prisoner. Some were eating, and some were standing around.

“The clock struck six, and at this instant, Courtright reached beneath the table and arose to his feet holding a six-gun Colt .45 in each hand, which he leveled on the officers. The officers jumped quickly to their feet and reached for their guns, but at the back of each officer were two men. These men each grabbed one arm of an officer, locking the arm behind their back. Courtright walked out through the back door. One of the fastest saddle horses in town was hitched in the alley. Courtright mounted the horse and skedaddled.

“My part in the arrangements was placing the guns at the end of the tables. I hung the guns from screw eyes by a light cord which would hold the gun’s weight but break easily. The table cloth hid the guns.”

That ends Andre Anderson’s first-hand account of Jim Courtright’s great escape. For comparison, here are some newspaper accounts:

In Dallas Norton’s Union Intelligencer of October 20 gave its account of Courtright’s escape amid “fifty or sixty friends well armed”: “The crowd surged to Second street and saw Courtright flying like the wind, and a mighty shout went up.”

As did the El Paso Daily Times on October 22.

And the Galveston Daily News told of Courtright’s escape on a “fiery-footed steed.”

Reaction to Courtright’s great escape was varied. For example, the chagrined county attorney, W. S. Pendleton (who would face some chagrin of his own in six years), complained that Courtright had been served “quail on toast and pistols under the table for dessert.”

The Fort Worth Gazette was equally chagrined, although it did not blame Courtright or his friends for their actions.

On October 24 the Gazette printed reactions from other Texas newspapers.

And now the rest of the story. Let us pick up the trail of the peripatetic Jim Courtright after he galloped away from the restaurant:

After his great escape, Courtright kept a low profile for fifteen months. On August 27, 1885 the Dallas Weekly Herald reported that Jim’s friend Tom Wilson was in town. (The Jim McEntire mentioned in this clip was also a suspect in the two New Mexico murders.) A reporter asked Wilson about the whereabouts of Courtright. Wilson said that Courtright had gone first to Galveston, then New York, then Kansas, Arizona, and South America, where he was “perhaps in the Chilian army. He is safe.” (Such a flight to South America calls to mind the travels of Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and Etta Place in 1902 after Butch, Sundance, and associates visited Fort Worth in 1900.)

But who knows if Wilson was telling the truth or was simply feeding the reporter (and any badge-wearing readers) a heapin’ helpin’ of red herring.

Regardless of where Courtright had been lying low, he was back in Fort Worth in February 1886 and gave himself up to Sheriff Walter Maddox.

But no hotel room, restaurant table, or jail cell could hold Jim Courtright long. He was soon out on bond and not only resumed operation of his T.I.C. detective agency but also was reinstated by Maddox as a Fort Worth peace officer: On April 3 Courtright, still under indictment for murder, was one of the officers guarding the ambushed train at the Battle of Buttermilk Junction.

Courtright found time even to contemplate show biz. In July the Galveston Daily News reported that Jesse James’s brother Frank was in Fort Worth to consult with Courtright about working up a touring “wild west show” based on the “checkered career” of the two men.

The Frank James-Jim Courtright show would include a dramatization of Courtright’s great escape from “the New Mexican officers” in 1884. Note that Courtright stipulated to Frank James that their show not tour in New Mexico. (Photo of Frank James from Wikipedia.)

Nonetheless, Courtright dutifully went back to New Mexico to stand trial, but the murder charges against him were dropped in November 1886. Courtright returned to Fort Worth and his detective agency. He had dodged a murder rap. Life looked good again.

But Jim Courtright had only nine weeks left to live.

On a winter’s night early in 1887, Courtright would meet Luke Short outside the White Elephant Saloon, located at 308-310 Main Street (labeled WE on the map), just across the street from Merchants’ Restaurant (labeled M on the map), from which in 1884 Courtright had made his daring escape and galloped away, “flying like the wind.”

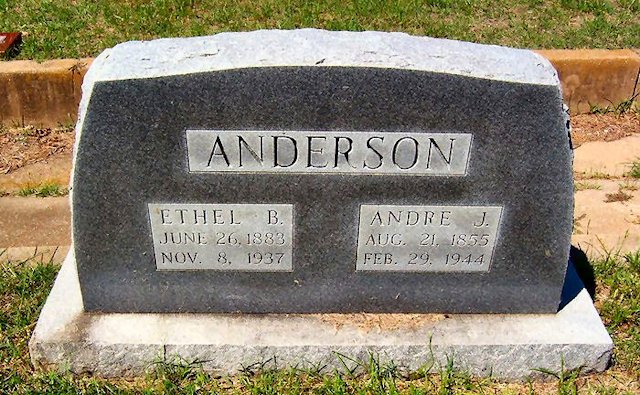

Andre Anderson is buried in Oakwood Cemetery . . .

close enough to the grave of Jim Courtright that Anderson could help once again if Jim were to try his greatest escape.

close enough to the grave of Jim Courtright that Anderson could help once again if Jim were to try his greatest escape.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

I find myself reading your blog almost daily. Thank you. It’s my favorite. Can you comment on why Timothy Isaiah “Longhair Jim” is also known as Thomas Isaiah in the 1878 and 1885 Fort Worth City Directories? Were Timothy/Thomas interchangeable back in the day?

Thank you! Good question. Two biographies of Courtright say that his shortened first name “Tim” got corrupted into “Jim” and stuck, possibly about the time of the Civil War.

Your research is sensational! I love your blog.

Thank you, Howard. I have learned so much in the six-plus years I have been writing this blog.

This is the type of story that makes great movies!

It is indeed. And this is one reason why I like to include contemporary accounts-first-person and newspapers. They help to show that such wild West stories are grounded in fact.

great story that has a lot of well written meaning things people cant eyeball when they go 19th century….. it is a place to dream drift and fall into the cracks of time with…….we should all take note what makes great history……thanks for a great story, Alexander Troup, Research Art and History.