Lancaster Avenue has had “East” and “West” designations ever since the street name was created in 1931 when North Street and East Front Street downtown and the Fort Worth-Dallas Pike on the East Side were renamed “Lancaster Avenue” to honor the president of the Texas & Pacific railroad. But even after the name change, until 1939 West Lancaster Avenue was also divided into east and west: east West Lancaster from Main Street to the waterworks and west West Lancaster from Montgomery Street to Foch Street, completed in 1936 in time for the Frontier Centennial.

Between the east and west sections of West Lancaster lay the Clear Fork of the Trinity River.

And believe it or not, in 1936 the West 7th Street bridge was the only crossing of the Clear Fork between Henderson Street and today’s West Vickery Boulevard.

But on February 25 in a brief at the bottom of an inside page of the Star-Telegram there was good news for motorists: Commissioners Court had asked the State Highway Commission to build a bridge over the river for the planned extension of Lancaster Avenue.

On this 1937 map the yellow line indicates the gap between the two parts of West Lancaster Avenue at the river. At the intersection of Burleson Street (today’s University Drive) and West Lancaster, note “Van Zandt West” school where the parking lot of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth is and Frontier Fiesta where Casa Manana and the Will Rogers complex are today. Farrington Field had not been built. Also shown was the old Chevrolet plant. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

The city’s growth demanded a second east-west bridge over the Trinity west of downtown, but connecting the east and west sections of West Lancaster Avenue would be an engineering challenge because of what separated the two sections: the Clear Fork, Trinity Park, and two railroad tracks.

In 1937 the State Highway Department advertised for bids on construction of approaches to a bridge to connect the two West Lancasters. Note that the workers would be paid a minimum wage ranging from $1 ($16.68 today) for skilled labor to forty cents ($6.67 today) for unskilled labor.

In 1937 the State Highway Department advertised for bids on construction of approaches to a bridge to connect the two West Lancasters. Note that the workers would be paid a minimum wage ranging from $1 ($16.68 today) for skilled labor to forty cents ($6.67 today) for unskilled labor.

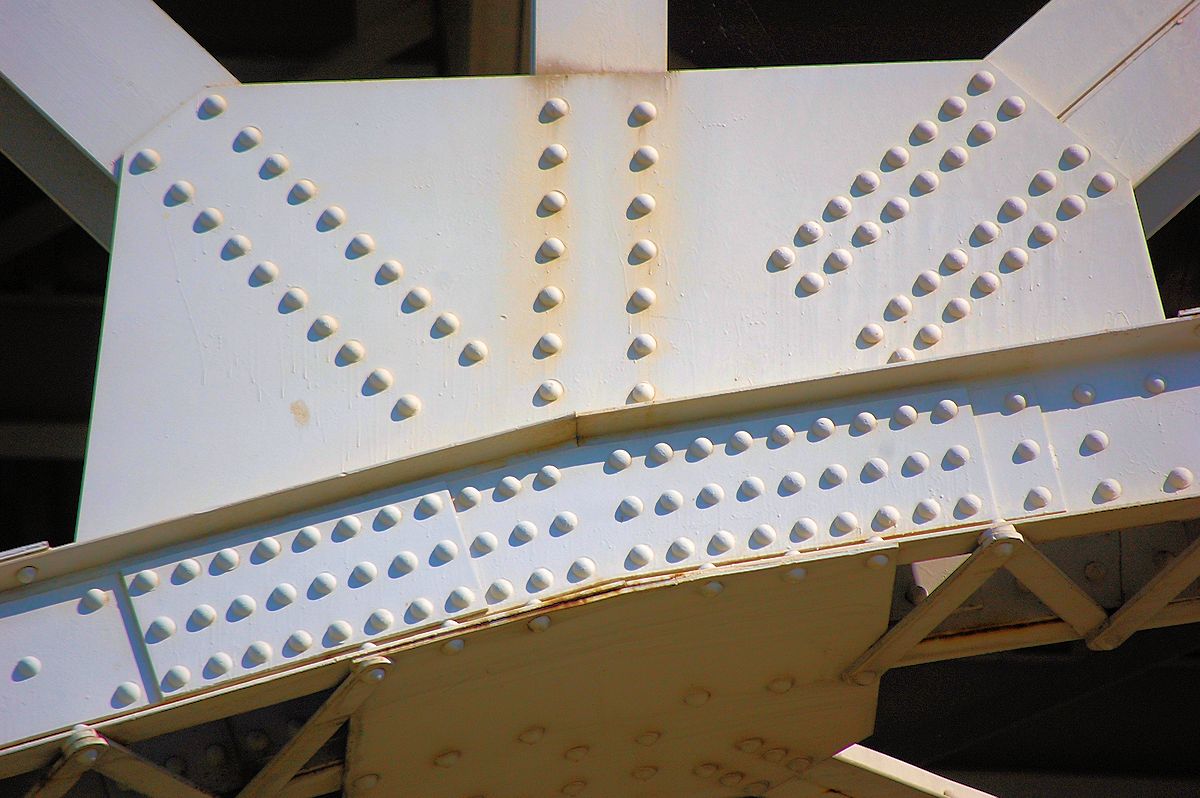

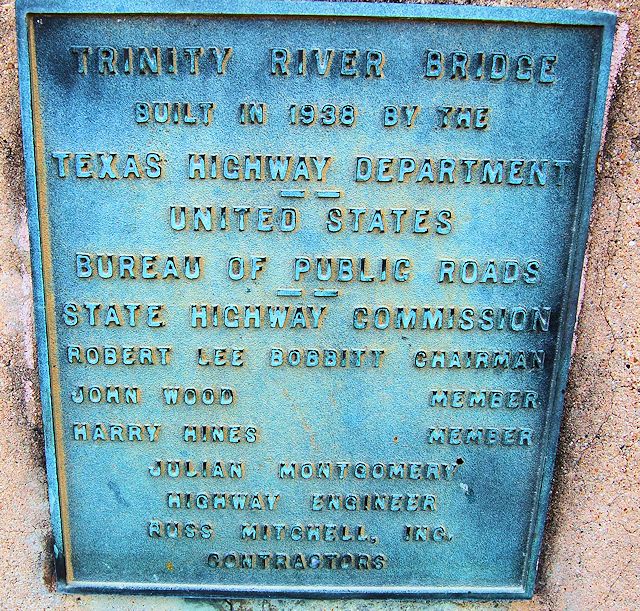

By March 1939 the new 2,868-foot bridge was almost completed. The bridge was expected to carry four thousand vehicles a day, alleviating traffic on the overtaxed West 7th Street Bridge. The Lancaster bridge contained 4.7 million tons of steel. In addition to designing a bridge to “jump” the river, the park, and two railroad tracks, engineers faced another challenge: At ninety feet tall, the river bluff on the east end of the bridge was too elevated for the bridge to reach, so the highway department was considering either digging a tunnel for Lancaster under Penn and Texas streets to Ballinger Street or cutting through the bluff to carry Lancaster to Ballinger Street (see below). The news article mentions Farrington Field, which would open in September. The article also mentions the bridge’s iconic terracotta longhorns (photo below).

By March 1939 the new 2,868-foot bridge was almost completed. The bridge was expected to carry four thousand vehicles a day, alleviating traffic on the overtaxed West 7th Street Bridge. The Lancaster bridge contained 4.7 million tons of steel. In addition to designing a bridge to “jump” the river, the park, and two railroad tracks, engineers faced another challenge: At ninety feet tall, the river bluff on the east end of the bridge was too elevated for the bridge to reach, so the highway department was considering either digging a tunnel for Lancaster under Penn and Texas streets to Ballinger Street or cutting through the bluff to carry Lancaster to Ballinger Street (see below). The news article mentions Farrington Field, which would open in September. The article also mentions the bridge’s iconic terracotta longhorns (photo below).

On June 14, 1939 the $675,000 ($11.6 million today) Lancaster Avenue Bridge was opened, connecting the two sections of West Lancaster Avenue and connecting Fort Worth on the east and west sides of the Trinity River.

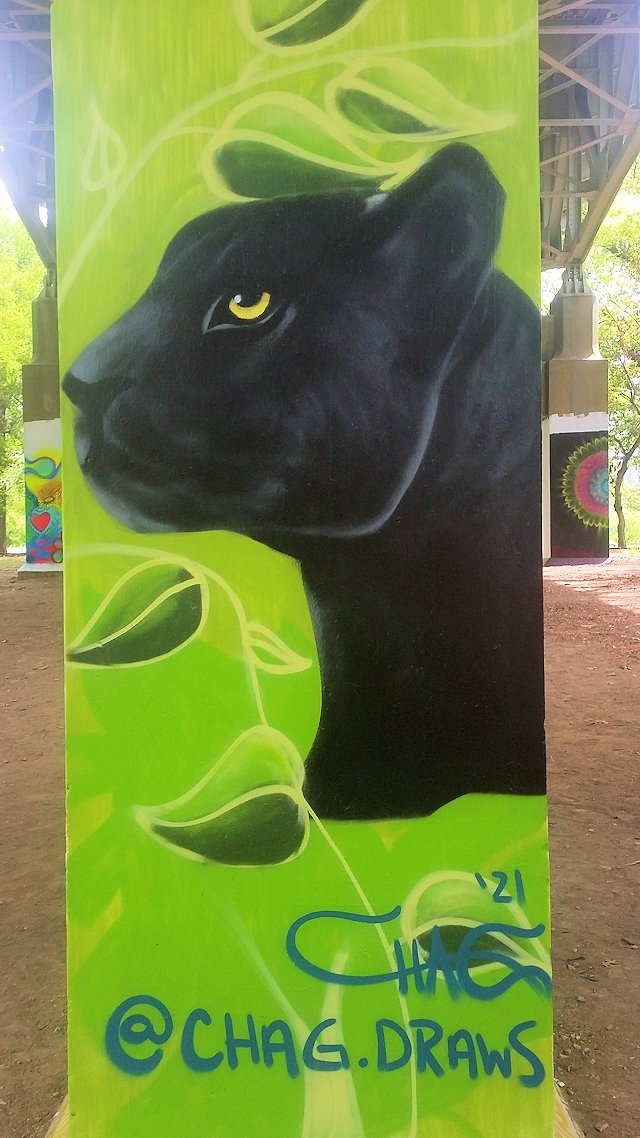

Some views of the Lancaster Avenue Bridge:

The bridge viewed from the West 7th Street Bridge.

The bridge viewed from the West 7th Street Bridge.

The bridge has four niche benches flanked by terracotta longhorns.

Note that the 1939 news clips indicate that access to the bridge on the east would be from Fournier Street unless a connecting roadbed was laid from the bridge through the river bluff at Penn Street via a tunnel or laid over the bluff to Summit Avenue. Instead a compromise was used: The bluff was cut from east of Fournier Street to Summit Avenue. An art deco retaining wall was erected on each side of the cut along Lancaster.

When the bridge was built, several Quality Hill mansions still survived on Summit Avenue and Penn Street. For example, W. T. Waggoner’s mansion was on the south side of the cut; the Pollock-Capps house was on the north side of the cut. Perhaps that rarefied real estate explains the fancy retaining walls and two sets of steps down to Lancaster from Penn Street.

One of the stairwells from the bridge deck down to Trinity Park.

One of the stairwells from the bridge deck down to Trinity Park.

From the Phyllis J. Tilley Memorial Bridge. The new West 7th Street Bridge is in the background.

From the Phyllis J. Tilley Memorial Bridge. The new West 7th Street Bridge is in the background.

Note the name “Harry Hines,” as in the Dallas boulevard.

Your articles are awesome! I have really enjoyed reading them. My family, the Oldham’s were original Ft Worth merchants, so I believe. Leigh Oldham died on a cattle drive to Illinois in 1866 and his brother, Lane operated in Millican, Ft Parker, Weatherford and later at 16 Houston Street in the late 1870’s. He too died young in 1880. His children were raised by George B. Loving, son of Oliver and a newspaper publisher. They lived at 1221 North Street, which, thanks to your article, appears to now be E Lancaster. If you could share any information about the Oldham’s or Loving’s I would be very appreciative. Thanks, Gary Davis 936.32.7.0644

Thanks, Gary. I have a post on the Lovings here.

Thanks for the history lesson!

Thanks, Steven. I probably am learning more than anyone.

I think we should name one for Townes.

Wouldn’t be hard to do: Formally the West 7th Street Bridge is the “Van Zandt Viaduct.”

I’ve always assumed the stairs were because so many people still walked in those days….It may not make an extensive blog…but could you try to find out why there was a Van Zandt West school and an East Van Zandt school….The west, of course, on University and Lancaster, and the east on Missouri Avenue….A few miles from each other…almost seems as though some naming authority didn’t initially know there was already a school with that name….

Dan, west was named for K. M., who owned most of that part of town. East was named for his father, Isaac.