It was built for a whopping $55,000—just over $1 million in 1883 dollars. It was opulent. It was state-of-the-art. And more than a century before the city adopted the slogan, it was to transform Fort Worth into “the city of cowboys and culture.”

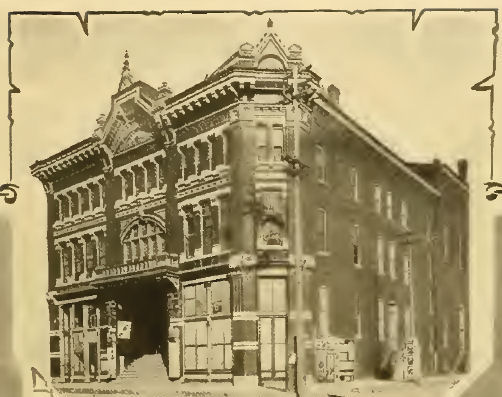

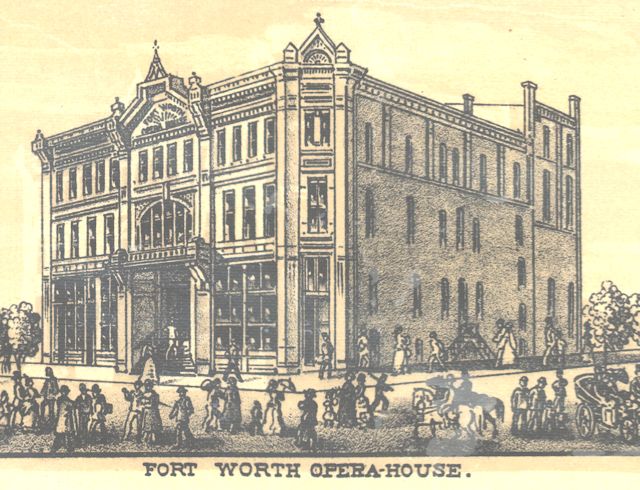

Fort Worth already had the cowboys, of course. And what a contrast they must have made with the new Fort Worth Opera House, located at 3rd and Rusk (now Commerce) streets just east of the first Knights of Pythias lodge hall. The opera house was built by a syndicate headed by Walter Ament Huffman. (Images from Greater Fort Worth, 1907, and Wellge map, 1886.)

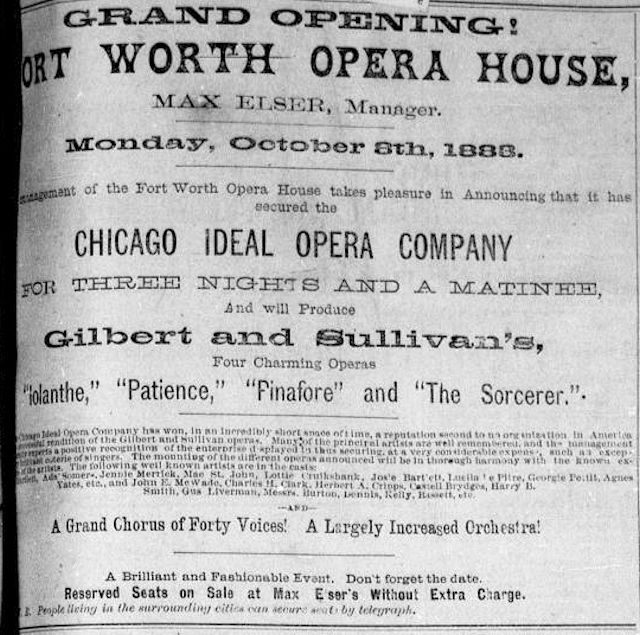

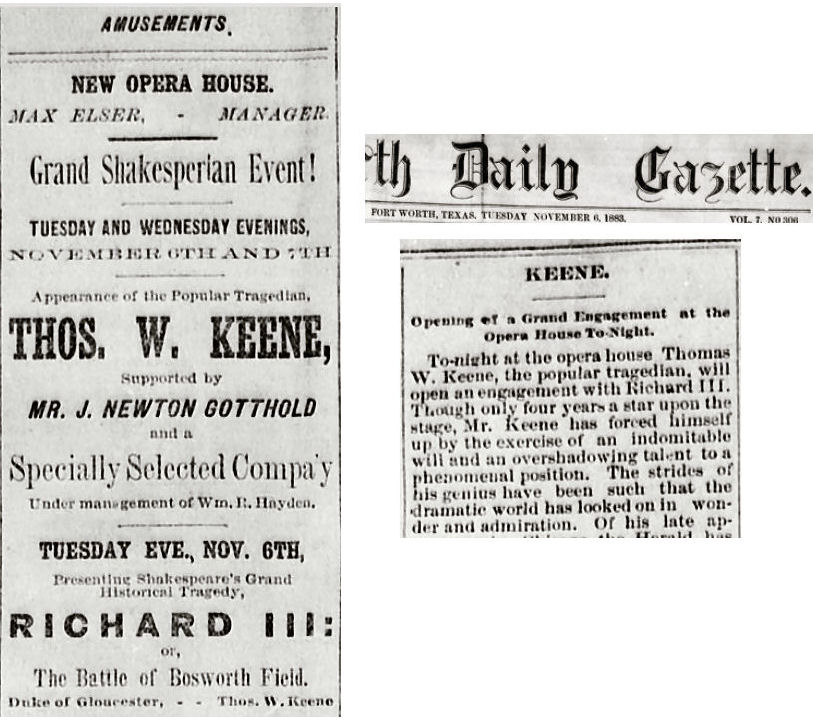

The opera house opened on October 8, 1883, managed by the ubiquitous Max Elser. The Chicago Ideal Opera Company presented “four charming operas” by Gilbert and Sullivan. Clip is from the September 30 Fort Worth Daily Gazette.

The opera house opened on October 8, 1883, managed by the ubiquitous Max Elser. The Chicago Ideal Opera Company presented “four charming operas” by Gilbert and Sullivan. Clip is from the September 30 Fort Worth Daily Gazette.

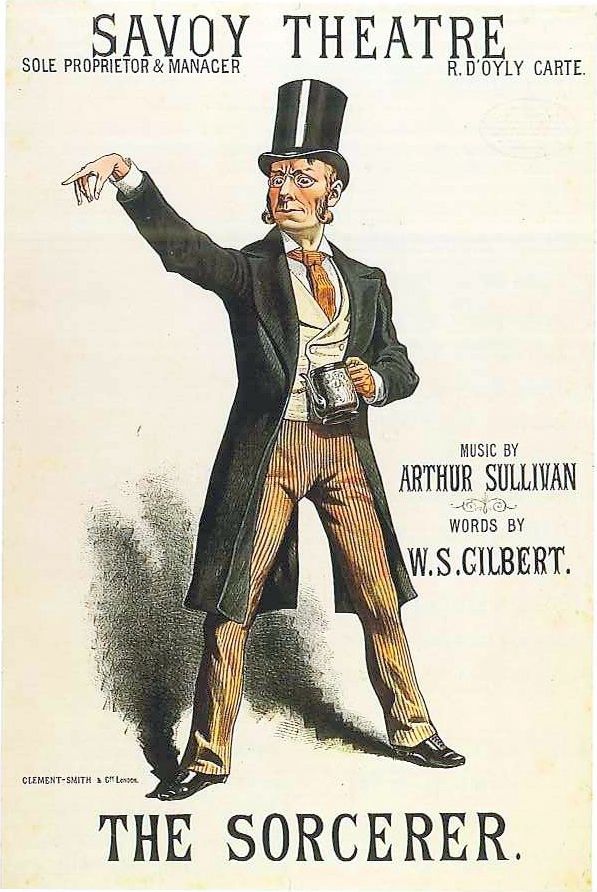

One of the four plays presented on opening night of the Fort Worth Opera House was The Sorcerer. (1884 poster from Wikipedia.)

One of the four plays presented on opening night of the Fort Worth Opera House was The Sorcerer. (1884 poster from Wikipedia.)

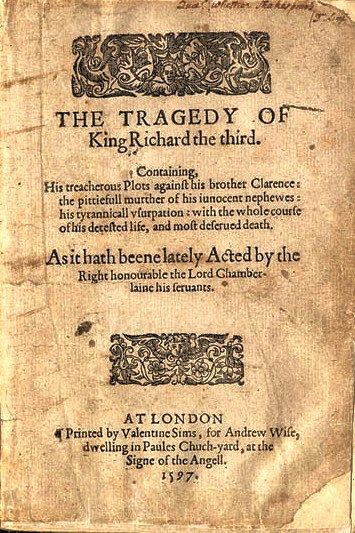

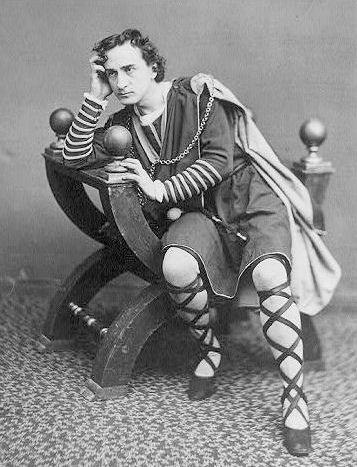

The opera house had been open less than a month when it presented Shakespeare’s Richard III.

The opera house had been open less than a month when it presented Shakespeare’s Richard III.

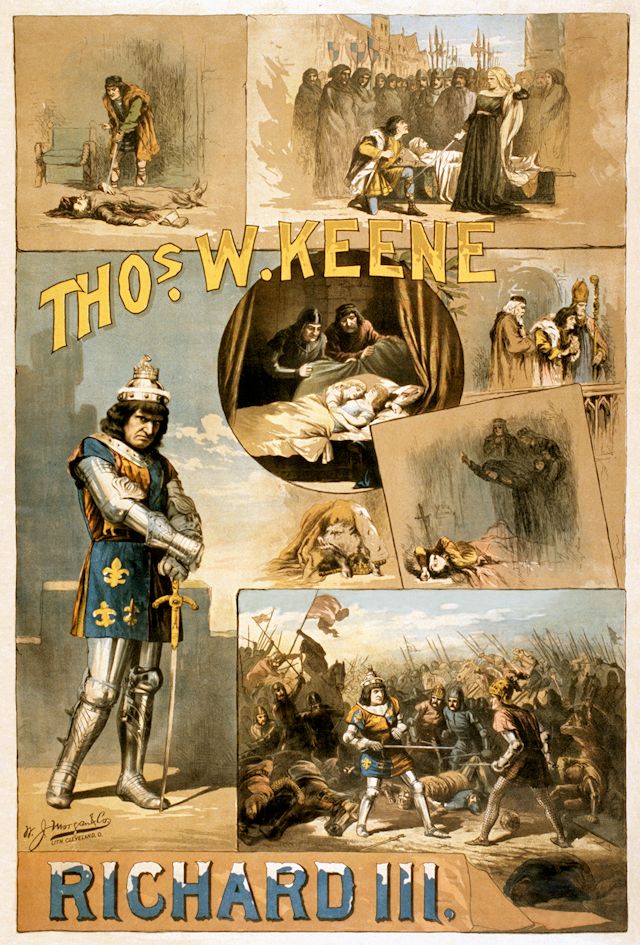

Thomas W. Keene took to the Cowtown stage as the villainous Richard III on November 6, 1883. This poster is from 1884.

Thomas W. Keene took to the Cowtown stage as the villainous Richard III on November 6, 1883. This poster is from 1884.

As an American Shakespearean, Keene was regarded as second only to Edwin Booth, brother of John Wilkes Booth. (Images from Wikipedia.)

Consider the time and the place: In 1883 Fort Worth was a rough-and-tumble frontier town whose iconic wild West moments—the Battle of Buttermilk Junction and the Courtright-Short gunfight—were still in the future. Not the best venue, perhaps, for men to traipse around on stage wearing what appeared to be skirts and stovepipe on their legs.

After all, the stage that cowboys could relate to best was pulled by six horses and took seventeen days to get from Fort Worth to Yuma, Arizona.

And when Richard III opened the play with

“Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York;

And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried,”

the thoughts of many a cowboy in the audience probably drifted back to the “deep bosom” of a dance hall girl he had met in Hell’s Half Acre.

Nonetheless, the Gazette was enthusiastic about Keene’s performance.

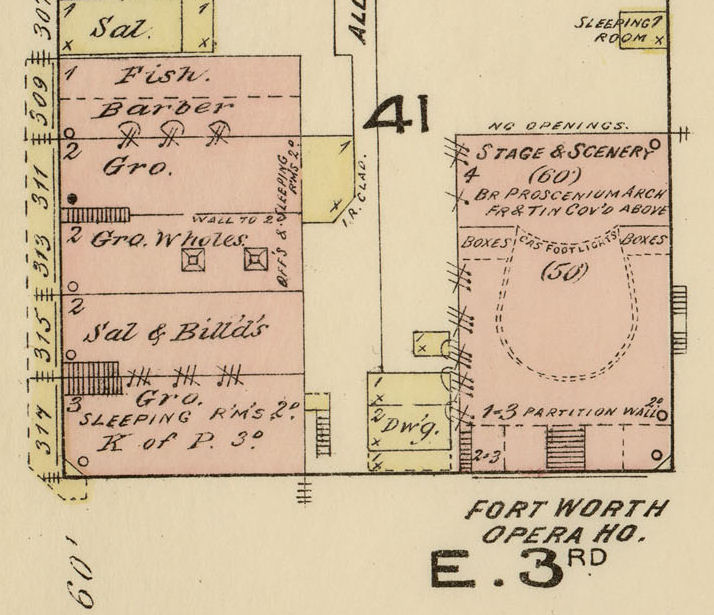

The Fort Worth Opera House offered entertainment ranging from the Bard to burlesque, from divas to minstrels to trapeze artists. At four stories it was one of the tallest buildings in town. It seated 1,200 patrons at admission prices ranging from 50 cents to $1.50. The stage, measuring thirty-two by sixty-eight feet, was outfitted with sets to reproduce any scene from a palace to a prison. The new opera house was the Bass Performance Hall of its time. (Map is Sanborn, 1885.)

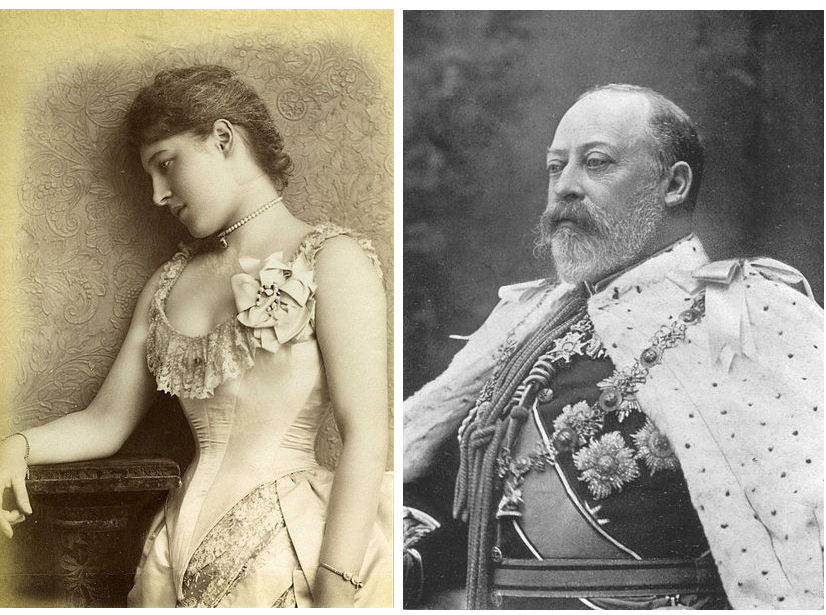

All the big names in theater performed at the opera house, including James O’Neill (father of playwright Eugene O’Neill), Lillian Russell, Sarah Bernhardt, and Edwin Booth himself, who performed Hamlet (see photo) here in 1888. John L. Sullivan even gave a boxing demonstration.

In 1888 Lillie Langtry, British actress and former paramour of future King Edward VII, also trod the boards at the opera house. As Langtry left New Orleans to tour Texas in her seventy-five-foot custom rail coach, she left behind most of her jewelry because she was afraid that in Texas she would be “held up by cowboys.”

After the death of Huffman in 1890, theatrical manager Phil Greenwall bought the opera house from Huffman’s heirs. The opera house then operated as “Greenwall’s Opera House.”

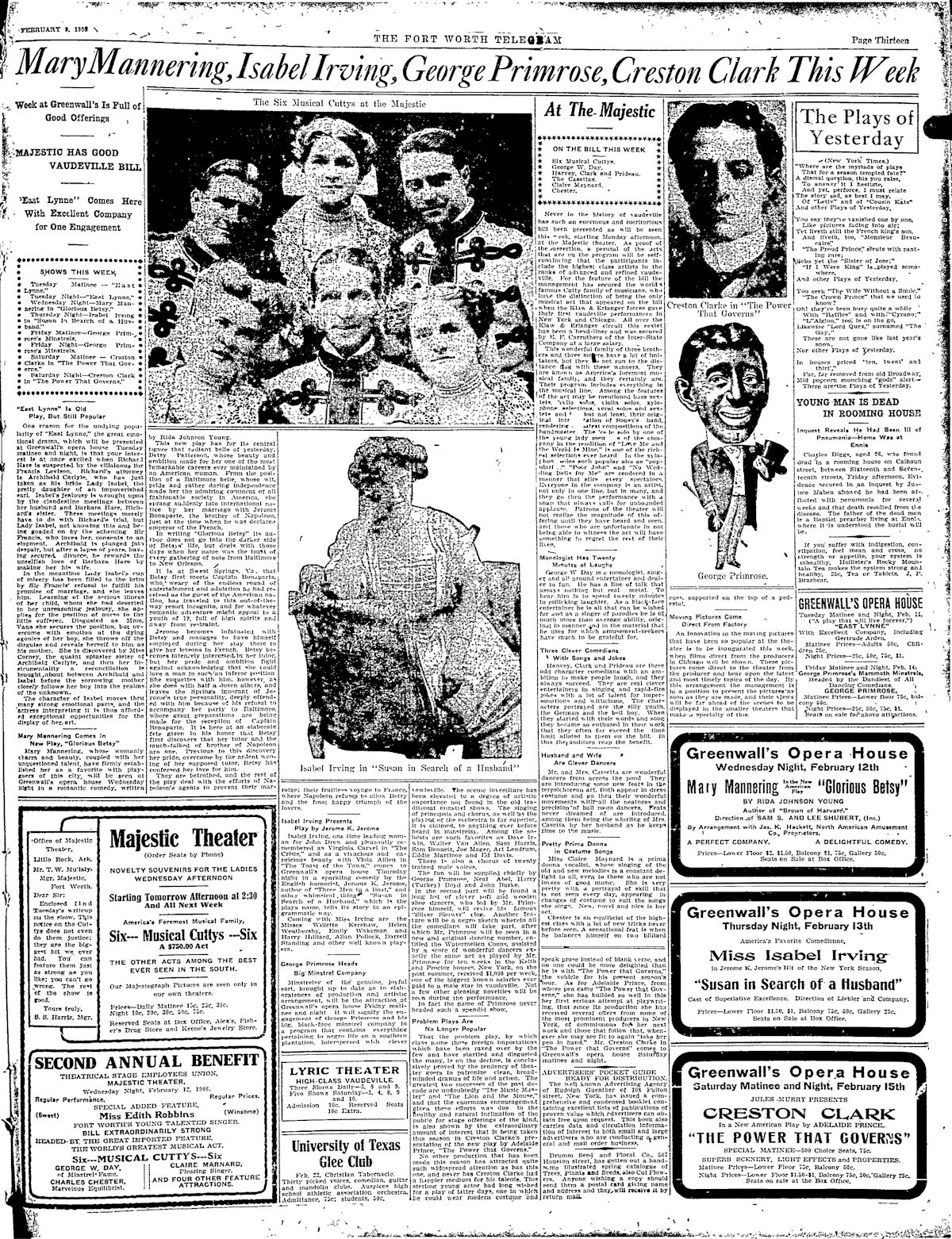

By 1908 the Telegram printed a full page of theater news and ads on Sundays. Greenwall’s competed with other theaters such as the Majestic and Lyric.

By 1908 the Telegram printed a full page of theater news and ads on Sundays. Greenwall’s competed with other theaters such as the Majestic and Lyric.

But just three days after those ads appeared in 1908, the opera house was damaged by high winds, abandoned, and soon after torn down. Later that year A. T. Byers built an imposing new opera house, designed by Sanguinet and Staats (and managed by Greenwall) at East 7th and Rusk streets where a livery stable had previously stood.

But just three days after those ads appeared in 1908, the opera house was damaged by high winds, abandoned, and soon after torn down. Later that year A. T. Byers built an imposing new opera house, designed by Sanguinet and Staats (and managed by Greenwall) at East 7th and Rusk streets where a livery stable had previously stood.

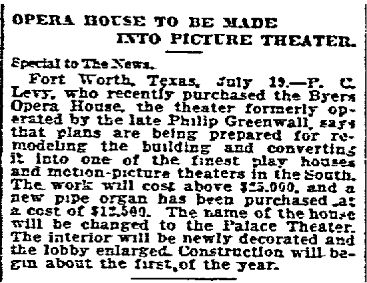

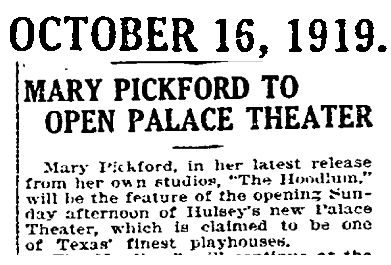

Byers Opera House in 1919 was converted to show motion pictures and became the Palace Theater—the first of the three theaters on Show Row.

Byers Opera House in 1919 was converted to show motion pictures and became the Palace Theater—the first of the three theaters on Show Row.

Lily Langtry, no wonder Judge Roy Bean was in love with her.

The Kardashian of her time. But unlike a lot of British who came over here, she didn’t stay.