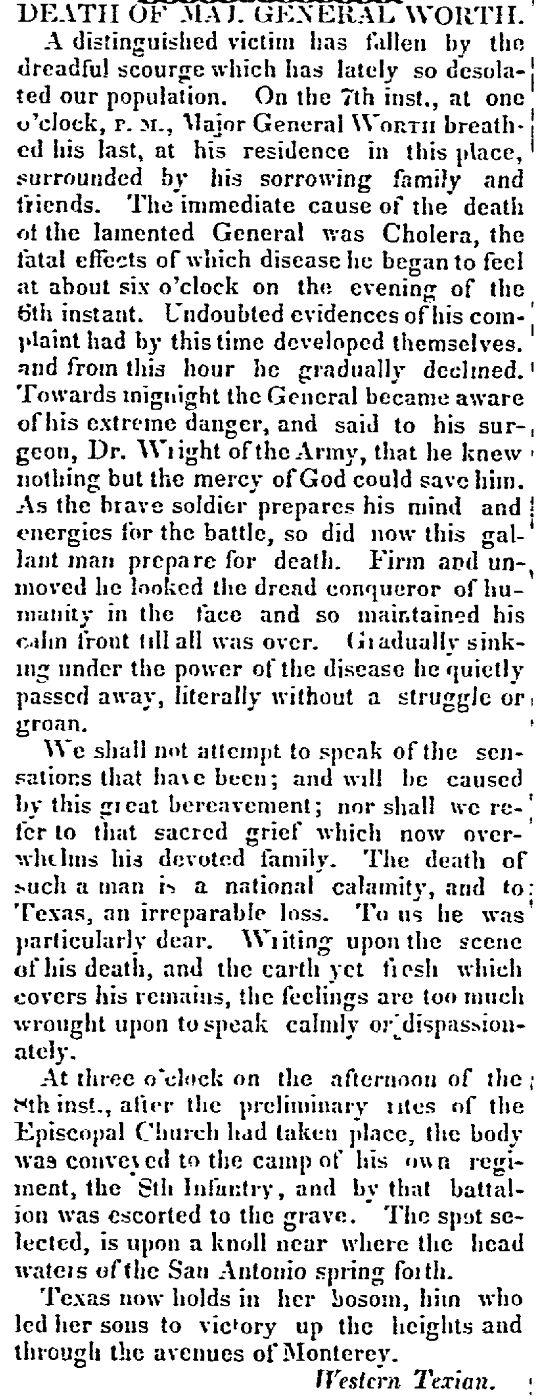

On May 7, 1849 Major General William Jenkins Worth died of “the dreadful scourge” of cholera in San Antonio.

News traveled slowly in those days: Five weeks after General Worth died the June 16 edition of the Northern Standard of Clarksville, Texas reprinted a news report that had appeared in the Western Texian of San Antonio. (Newspapers relied on an exchange system: Each newspaper gathered and disseminated news by exchanging copies of its editions with editions of other newspapers by mail.) General Worth was buried in Brooklyn.

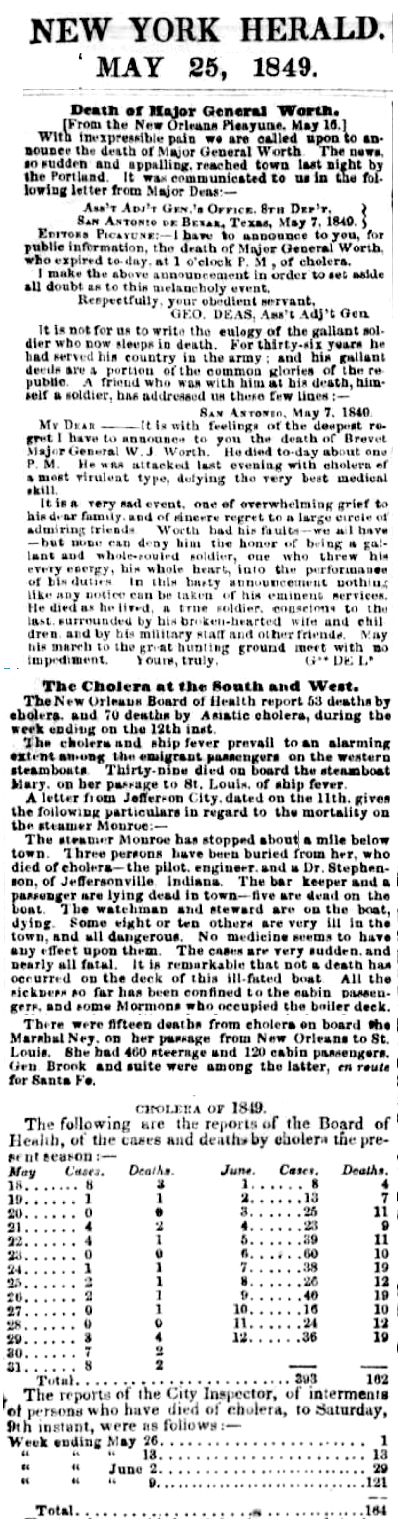

General Worth was one of tens of thousands of people killed worldwide by the cholera pandemic of 1849. The May 25, 1849 issue of the New York Herald published news of General Worth’s death and under that news a report on cholera in the South and West. By mid-June cases of cholera in New York City had increased. The bottom clip lists cholera deaths in the city by day.

General Worth was one of tens of thousands of people killed worldwide by the cholera pandemic of 1849. The May 25, 1849 issue of the New York Herald published news of General Worth’s death and under that news a report on cholera in the South and West. By mid-June cases of cholera in New York City had increased. The bottom clip lists cholera deaths in the city by day.

Cholera, spread from continent to continent by people sailing on ships and by people traveling overland trade routes, in 1849 killed 14,000 in London, 5,000 in Liverpool, 200,000 in Mexico. In the United States cholera killed 5,000 in New York City, 4,500 in St. Louis, 3,000 in New Orleans. Thousands of immigrants traveling west along the California, Mormon, and Oregon trails during the gold rush that year died of cholera. Cholera also killed ex-President James K. Polk in 1849.

One month after General Worth died, Army Major Ripley Arnold, accompanied by Texas Ranger Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson and a few soldiers, scouted the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River and selected a site on which to establish an Army fort in northern Texas. The fort would be part of a line of military outposts stretching along the frontier to protect white settlers against Native American “depredations.” On June 6, 1849 Major Arnold, with the raising of Old Glory on a flagpole northwest of today’s courthouse, established the Army’s Camp (soon to be “Fort”) Worth and named the camp in honor of General Worth, his former commander.

William Jenkins Worth was born in New York in 1794. President of the United States at the time: George Washington. Worth fought in the War of 1812, the Second Seminole War of 1835-1842, and the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 (see below).

William Jenkins Worth was born in New York in 1794. President of the United States at the time: George Washington. Worth fought in the War of 1812, the Second Seminole War of 1835-1842, and the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 (see below).

Now let’s back up a few years. Below are newspaper clippings—some of them first-person accounts—about the fort, the town, and some of the people who were here at the git-go. These clippings, in their aggregate, might serve as the book of Genesis for the fort named “Worth.”

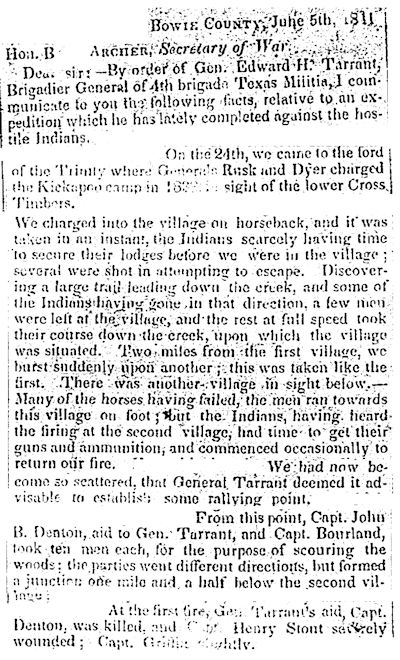

This report in the July 14, 1841 Austin City Gazette is a letter written to Republic of Texas Secretary of War Branch Archer. It relates details of the Battle of Village Creek fought on May 24 between General Edward H. Tarrant, Captain John Bunyan Denton, and other soldiers against Tonkawa, Caddo, and Cherokee warriors living in a string of villages along Village Creek near where today’s Lake Arlington lies.

This report in the July 14, 1841 Austin City Gazette is a letter written to Republic of Texas Secretary of War Branch Archer. It relates details of the Battle of Village Creek fought on May 24 between General Edward H. Tarrant, Captain John Bunyan Denton, and other soldiers against Tonkawa, Caddo, and Cherokee warriors living in a string of villages along Village Creek near where today’s Lake Arlington lies.

This hard-to-read clip from the October 7, 1843 (during the Republic of Texas) Red-Lander newspaper of San Augustine reads:

“Correspondence. Washington. Sept. 23d, 1843. A. W. Camfield: Having received instructions from Generals Terrell and Tarrant, Indian commissioners, Mr. Eldredge left here on the 20th for the neighborhood of Bird’s Fort, in company with Colonel Tom J. Smith. Nothing has been heard from the commissioners since I last wrote you. Yours, S.”Some context: The aforementioned generals George W. Terrell and Edward H. Tarrant, Indian commissioners of the Republic of Texas, had instructed J. C. Eldredge, superintendent of Indian affairs for the republic, to go from Washington (not Washington, D.C. but rather Washington-on-the-Brazos, the capital of the republic) to Bird’s Fort (in present-day north Arlington). Traveling with Eldredge was Thomas Smith, a Texas Ranger and Indian agent. Again news traveled slowly: By the time this article appeared in a newspaper, Tarrant and Terrell had already negotiated the Treaty of Bird’s Fort on September 29, 1843. The treaty was intended to end hostilities between white settlers of the republic and several tribes. The republic sought such a treaty in part because of the Battle of Village Creek in 1841.

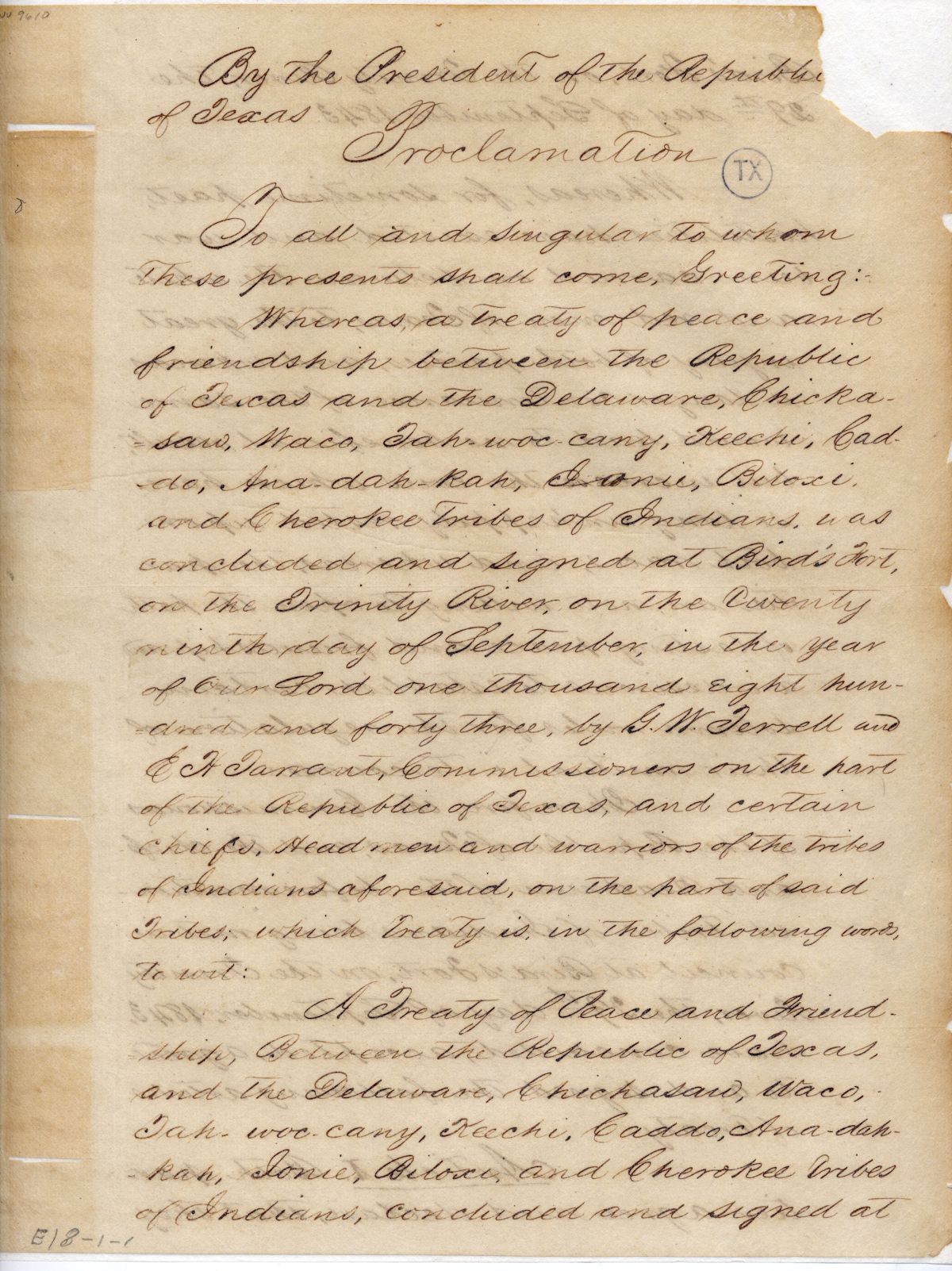

Page 1 of the treaty reads:

Whereas, a treaty of peace and friendship between the Republic

of Texas and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, was concluded and signed at Bird’s Fort, on the Trinity River, on the twenty ninth day of September, in the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty three, by G.W. Terrell and E.H. Tarrant, Commissioners on the part of the Republic of Texas, and certain chiefs, Headmen and warriors of the tribes

of Indians aforesaid, on the part of said Tribes; which treaty is, in the following words, to wit:

A Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Between the Republic of Texas,

and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-Dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, concluded and signed at

(Photo from Texas State Library & Archives Commission.)

Article I of the treaty reads: “Both parties agree and declare, that they will forever live in peace and always meet as friends and brothers. Also, that the war which may have heretofore existed between them, shall cease and never be renewed.”

That peace didn’t come to pass, and six years later Texas, by then part of the Union, was deemed to need more forts, one of which was Fort Worth.

General Tarrant, for whom the county is named, was also a soldier and state legislator. He was born in South Carolina, fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, fought at the Battle of Village Creek in 1841. He is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

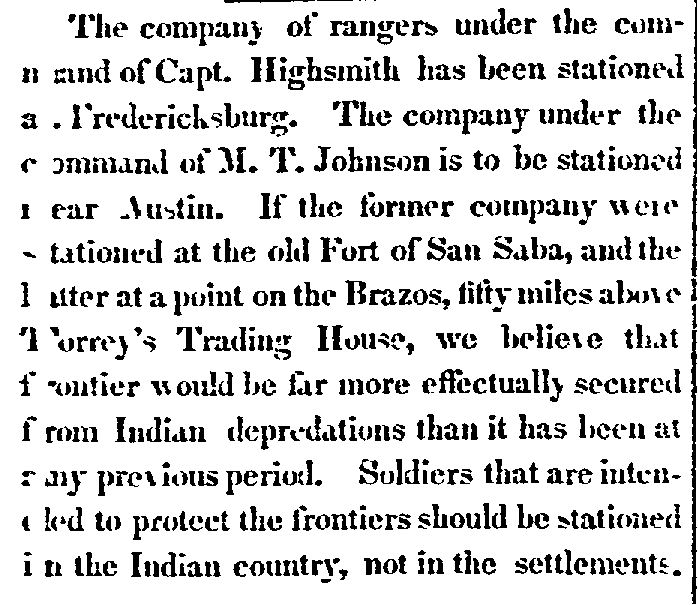

Middleton Tate Johnson, born in South Carolina, was stationed in the Hill Country in 1847, the Houston Telegraph reported. He later established Johnson’s Station in present-day south Arlington as a cotton plantation, ran for governor, is said by some historians to have donated the land for the Tarrant County courthouse in 1861. Johnson County is named for him.

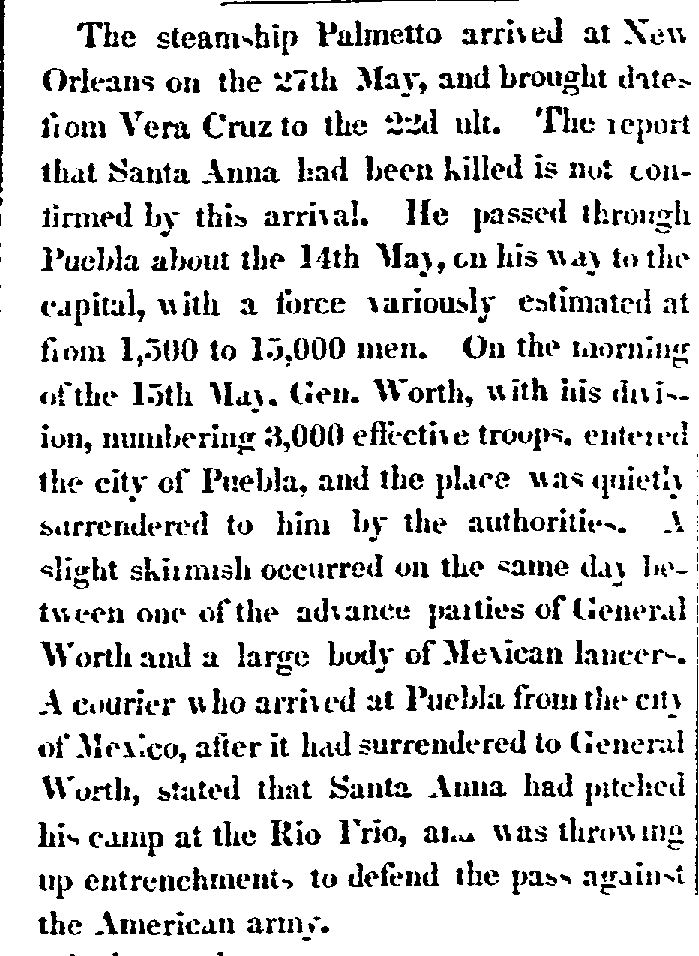

In 1847, during the Mexican-American War, the Houston Telegraph reported that General Worth had captured the city of Puebla, Mexico. Worth had been second in command to General Zachary Taylor at the beginning of the war in 1846. After the war Worth was placed in command of the Army’s Department of Texas in 1849. Major Arnold took command of Company F of the Second Dragoons after the war and was ordered to Texas to establish a military post “at or near the confluence of the West Fork and the Clear Fork of the Trinity River.”

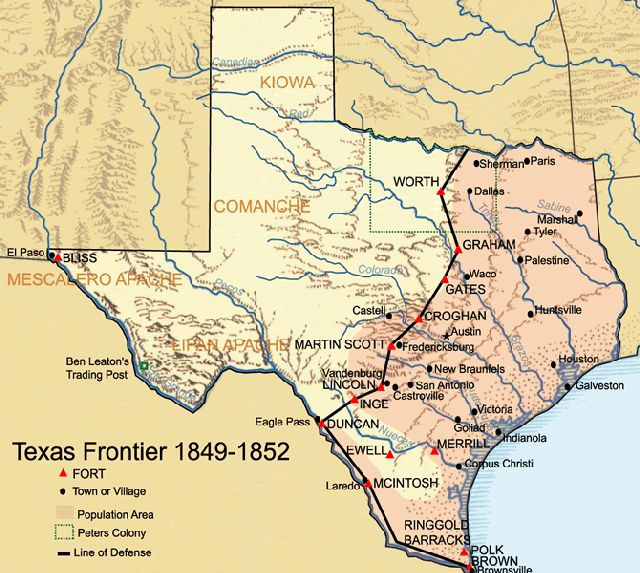

This map shows the line of forts along the western frontier in 1849-1852. Note that much of Peters Colony (dotted line) lay west of the frontier line. (Map from University of Texas Libraries.)

This map shows the line of forts along the western frontier in 1849-1852. Note that much of Peters Colony (dotted line) lay west of the frontier line. (Map from University of Texas Libraries.)

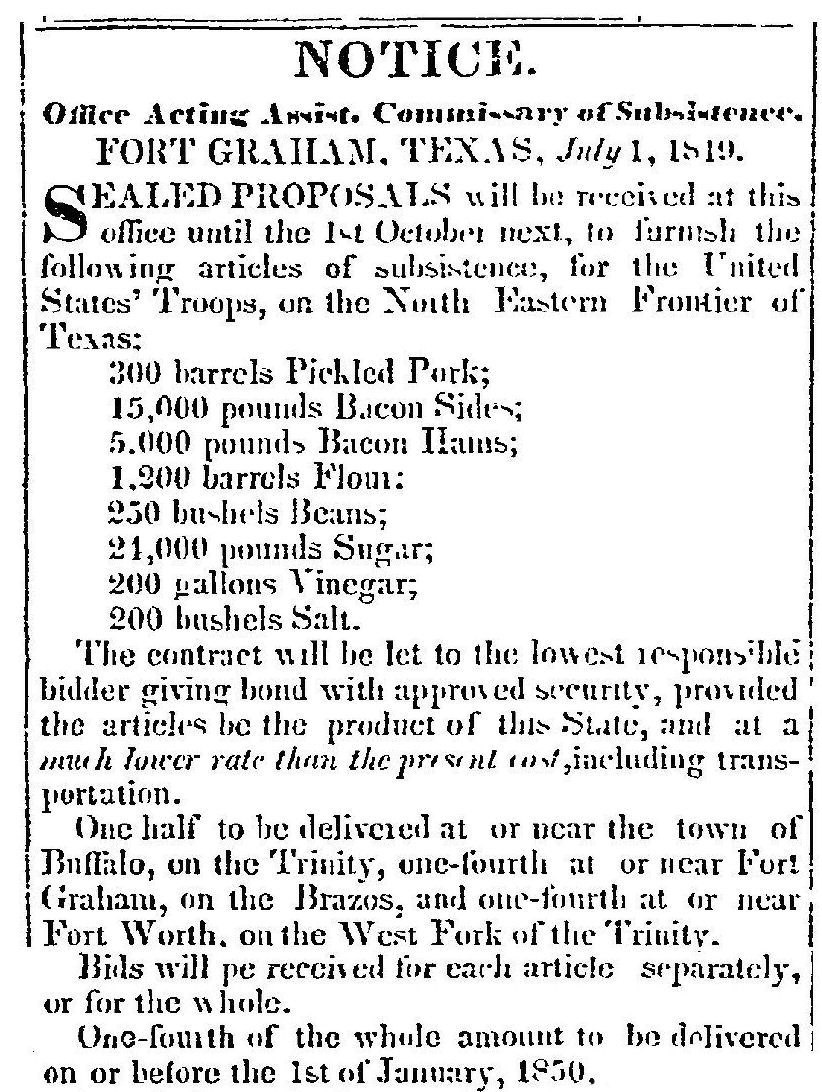

In July 1849 the Clarksville Standard published this notice soliciting bids from vendors to supply Army forts, including the new Fort Worth, with “articles of subsistence.”

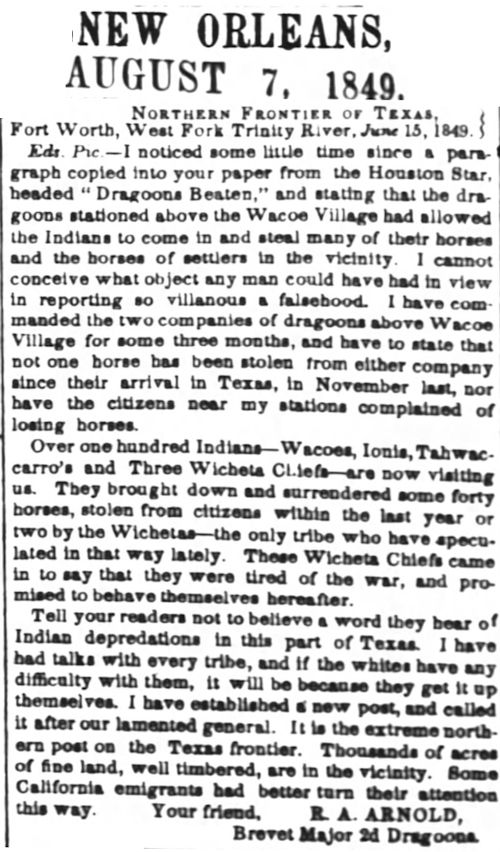

Just a few days after establishing Fort Worth, Major Arnold refuted a report of “Indian depredations” in the area. His refutation appeared seven weeks later in the New Orleans Picayune.

Just a few days after establishing Fort Worth, Major Arnold refuted a report of “Indian depredations” in the area. His refutation appeared seven weeks later in the New Orleans Picayune.

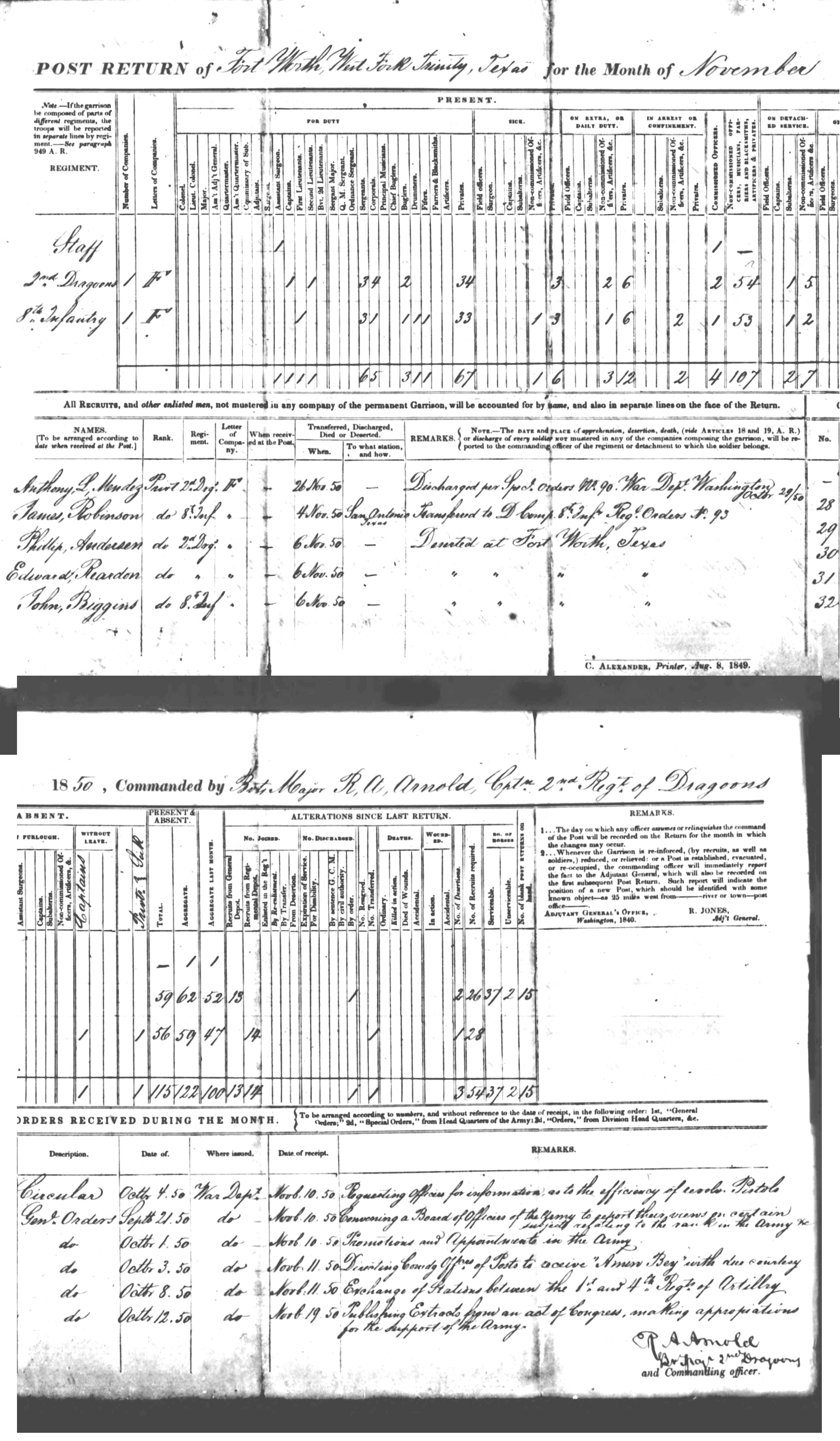

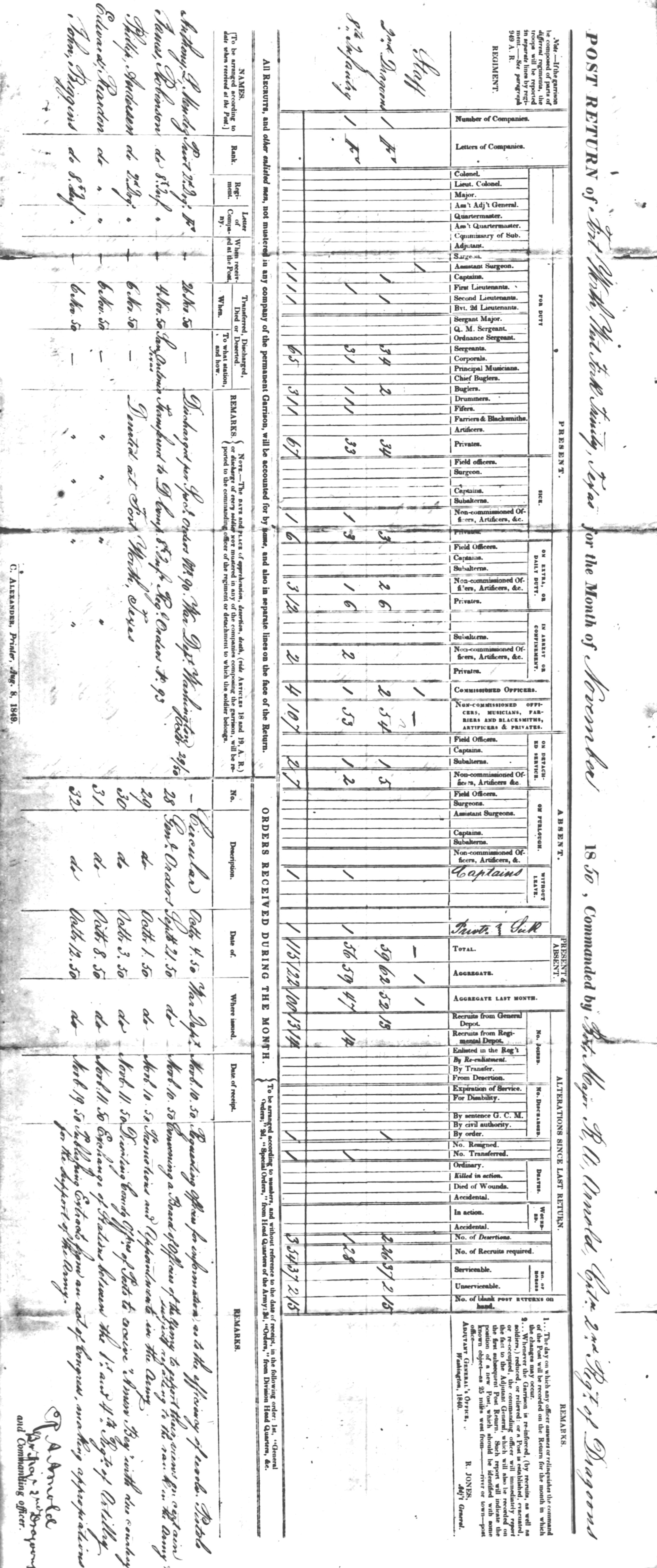

This is a post return filed by Major Arnold in November 1850 showing the composition of his troops, soldiers discharged or transferred, and so on at Fort Worth. I have both split the horizontal form and rotated it to make it larger and easier to read on a monitor. Arnold reported thirty-four privates in the Second Dragoons and thirty-three in the Eighth Infantry, no deaths or wounded, thirty-seven serviceable horses and two unserviceable, three desertions, no farriers or blacksmiths, three buglers, one drummer, and one fifer. (The 1850 federal census, which includes the population of the fort, is here.)

This is a post return filed by Major Arnold in November 1850 showing the composition of his troops, soldiers discharged or transferred, and so on at Fort Worth. I have both split the horizontal form and rotated it to make it larger and easier to read on a monitor. Arnold reported thirty-four privates in the Second Dragoons and thirty-three in the Eighth Infantry, no deaths or wounded, thirty-seven serviceable horses and two unserviceable, three desertions, no farriers or blacksmiths, three buglers, one drummer, and one fifer. (The 1850 federal census, which includes the population of the fort, is here.)

The Galveston Weekly Journal of 1852 reported that Major Hamilton Merrill’s Company B of the Second Dragoons was to replace Company F at Fort Worth. Major Arnold and Company F would move to Fort Graham (Hill County).

The Galveston Weekly Journal of 1852 reported that Major Hamilton Merrill’s Company B of the Second Dragoons was to replace Company F at Fort Worth. Major Arnold and Company F would move to Fort Graham (Hill County).

In this 1853 epistle to the Clarksville Standard the letter writer mentioned Frank Jordan’s encounter with a bear near Fort Worth.

In this letter to the Nacogdoches Chronicle a soldier described the journey from Johnson’s Station in present-day south Arlington to Fort Worth (crossing Sycamore Creek) just as the Army abandoned the fort on September 17, 1853. Major Merrill and his men moved first to Fort Mason in the Hill Country and then to Fort Belknap as the line of the frontier shifted westward. Texas Ranger Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson was helping General Thomas Jefferson Rusk (for whom Fort Worth’s Commerce Street originally was named) survey a proposed Southern Pacific rail line to El Paso. The “poor Denton” mentioned was minister and soldier John Denton, namesake of the city and county, who was killed at the Battle of Village Creek on May 24, 1841.

In this letter to the Nacogdoches Chronicle a soldier described the journey from Johnson’s Station in present-day south Arlington to Fort Worth (crossing Sycamore Creek) just as the Army abandoned the fort on September 17, 1853. Major Merrill and his men moved first to Fort Mason in the Hill Country and then to Fort Belknap as the line of the frontier shifted westward. Texas Ranger Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson was helping General Thomas Jefferson Rusk (for whom Fort Worth’s Commerce Street originally was named) survey a proposed Southern Pacific rail line to El Paso. The “poor Denton” mentioned was minister and soldier John Denton, namesake of the city and county, who was killed at the Battle of Village Creek on May 24, 1841.  The San Antonio Ledger of February 9, 1854 quoted the Dallas Herald as reporting progress in laying out the town site of Fort Worth after the Army had left in 1853. Some historians say Middleton Tate Johnson owned land where the fort was.

The San Antonio Ledger of February 9, 1854 quoted the Dallas Herald as reporting progress in laying out the town site of Fort Worth after the Army had left in 1853. Some historians say Middleton Tate Johnson owned land where the fort was.

Civilians such as John Peter Smith, Julian Feild, Ephraim Merrell Daggett, and Dr. Carroll Peak would make good use of the fort’s buildings after the Army abandoned it.

The Texas State Gazette reported the killing of Major Arnold at Fort Graham in 1853 and his subsequent reburial in Fort Worth in 1855. “Col. M. P. Johnson” surely is a typographical error referring to Colonel M. T. Johnson, who was indeed a Mason.

By 1856 Fort Worth had made “considerable advancement,” reported these visitors, who waxed ecstatic about the new town’s “delightful and picturesque scenery” and its “generous and hospitable people.”

By 1856 Fort Worth had made “considerable advancement,” reported these visitors, who waxed ecstatic about the new town’s “delightful and picturesque scenery” and its “generous and hospitable people.”

And who were these admiring visitors?

Why, they were editors of the Dallas Herald newspaper. Seems the intercity feud had not yet started in 1856.

But we can only speculate as to how it came about that those Dallas editors “borrowed some clothes” from Bob S.

I notice that one of the Johnson station May 6, 1853 article mentions a “member from the Holyland”. I wonder who that was and how they came to America on the Texas frontier?!! I didn’t think there would be anyone from the Middle East, and especially the Holy land coming over here at that time!

I can’t begin to explain that, if “Holy Land” means what we think it means. Mark Twain toured the Holy Land in 1867, but let’s face it: The Holy Land had more attractions than Johnson’s Station or Birdville. There were no trains, few stages in 1853. A foreign traveler likely would land at Galveston and travel overland over roads that we would call “ruts.” Nothing about it would have been touristy. Not a Stuckey’s in sight.

Another good history lesson, Mike. A personal note: my great-great-grandfather settled near Comanche Peak in the fall of 1855, two years after the soldiers vacated Fort Worth. Comanche raids were still common in that area, and after a year or so, he moved his family to Denton County, just east of present-day Rhome. That’s where they stayed.

Thanks, John. Your great-great-grandfather lived in a world we can’t imagine today.

Good article Mike. I see whee the solicitation for subsistence provisions included that they had to be Texas produced. Also liked the map of the location of the various forts.

Thanks, Ramiro. Interesting to read accounts of events when they were just news, not yet history. That is indeed an excellent map showing forts now largely unremembered, at least by us up here at Fort Worth. And it shows how huge the Peters Colony land was.