A century ago every city had them. Call them “slums,” call them “shanty towns,” they were enclaves of outgroups: immigrants, people of color. Fort Worth, like the rest of the South at the time, was segregated, and much of the ingroup (white Protestants) was quite open in the prejudices that sustained segregation. Newspapers identified nonwhites by race. City directories labeled Asians as “Chinese” (Hell’s Half Acre had a small Asian-American enclave at the turn of the twentieth century) and African Americans as “(c).” To the police, simply being brown or black all too often was deemed suspicious behavior.

From the perspective of the ingroup, enclaves kept outgroups contained (“in their place”). From the perspective of the outgroups, an enclave offered a sense of community and refuge even as it stigmatized and restricted.

In Fort Worth members of the ingroup gave outgroup enclaves names such as “Irish Town,” “Little Mexico,” “Little Africa.” Other enclaves had colorful names that belied the often-dire straits of their residents. Fort Worth had Yellow Row, Sticktown, Cabbage Patch, League of Nations, Hogan’s Alley. (See clip at bottom of post.) The names of other enclaves were more graphic. For example, the area of south downtown bounded by 13th Street and Vickery Boulevard, Jennings and Throckmorton streets had earned a name that surely made the chamber of commerce blanch: Bucket of Blood.

Real estate, of course, is all about location—for the poor as well as for the rich. The difference is that the rich get the desirable locations; the poor get what’s left over. Some outgroup enclaves were relegated to the Trinity River bottoms. Such land was not of value to the ingroup commercially or residentially because of the threat of flooding, so outgroups were welcome to it. In addition to contending with flooding, river bottom enclaves contended with mosquitoes and with the risk of disease from pollution in the river.

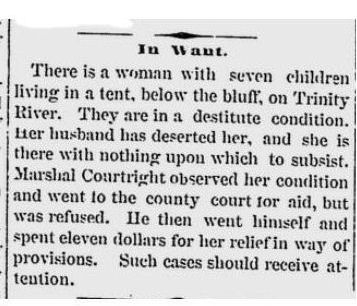

The river bottom below the courthouse bluff had long been the refuge of the have-nots. In 1877 City Marshal Jim Courtright with money from his own pocket helped a mother of seven who was living in a tent below the bluff.

The river bottom below the courthouse bluff had long been the refuge of the have-nots. In 1877 City Marshal Jim Courtright with money from his own pocket helped a mother of seven who was living in a tent below the bluff.

Other enclaves were located near the railyards (loud, dangerous) or the stockyards and packing plants (aromatic). Bum’s Bowery—an enclave of men who migrated by boxcar—was located along the Texas & Pacific railyard south of downtown. Rock Island Bottom was wedged between the river and the tracks of the Rock Island railroad east of downtown on land that was “formerly the city dumping ground.” On the North Side, a section of 22nd, 23rd, and 24th streets was Bohunk (an offensive term forged from Bohemia and a corruption of Hungary) Alley, an enclave of perhaps one thousand immigrants from Europe (Greece, Bulgaria, Russia, Serbia, Poland, Romania, Macedonia). Most did not speak English. They lived in “unspeakable conditions,” the Star-Telegram said, and worked at the packing plants, performing work “that most white men will not do, and work that many negroes have refused to do.”

Police occasionally raided outgroup enclaves and arrested “vagrants,” but to the ingroup Fort Worth’s outgroup enclaves were uninviting if not downright forbidding. (Rock Island Bottom was sometimes called “No Man’s Land.”)

And among the most forbidding enclaves was Battercake Flats.

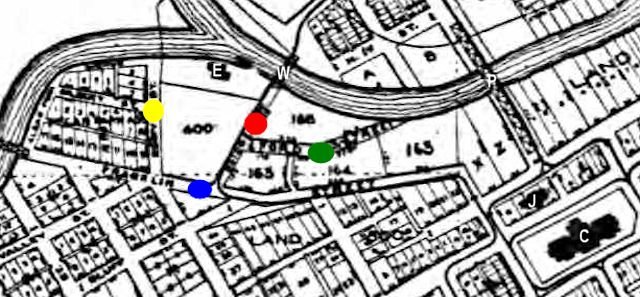

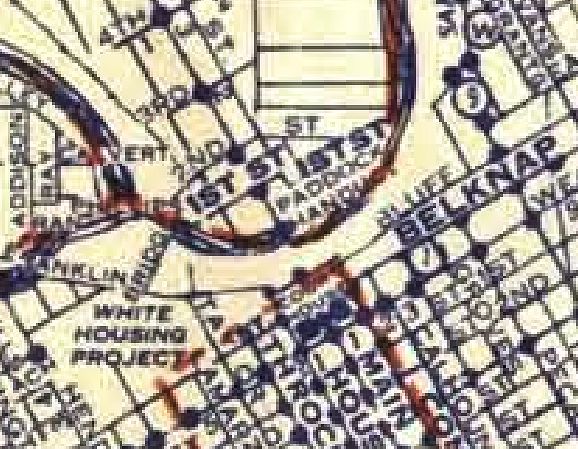

This 1909 map shows that Battercake Flats ironically was practically the back yard of two bastions of the ingroup power structure: the courthouse (C on map) and the county jail (J on map, replaced in 1918 by the Criminal Justice Building). The boundaries of the Flats were fluid over the years, but essentially the Flats was a wedge of land bounded by West Belknap Street and the Trinity River, stretching from the bluff behind the courthouse west past the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the river. Early in the twentieth century the city electric plant/waterworks (E) was located in the Flats near the confluence.

This 1909 map shows that Battercake Flats ironically was practically the back yard of two bastions of the ingroup power structure: the courthouse (C on map) and the county jail (J on map, replaced in 1918 by the Criminal Justice Building). The boundaries of the Flats were fluid over the years, but essentially the Flats was a wedge of land bounded by West Belknap Street and the Trinity River, stretching from the bluff behind the courthouse west past the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the river. Early in the twentieth century the city electric plant/waterworks (E) was located in the Flats near the confluence.

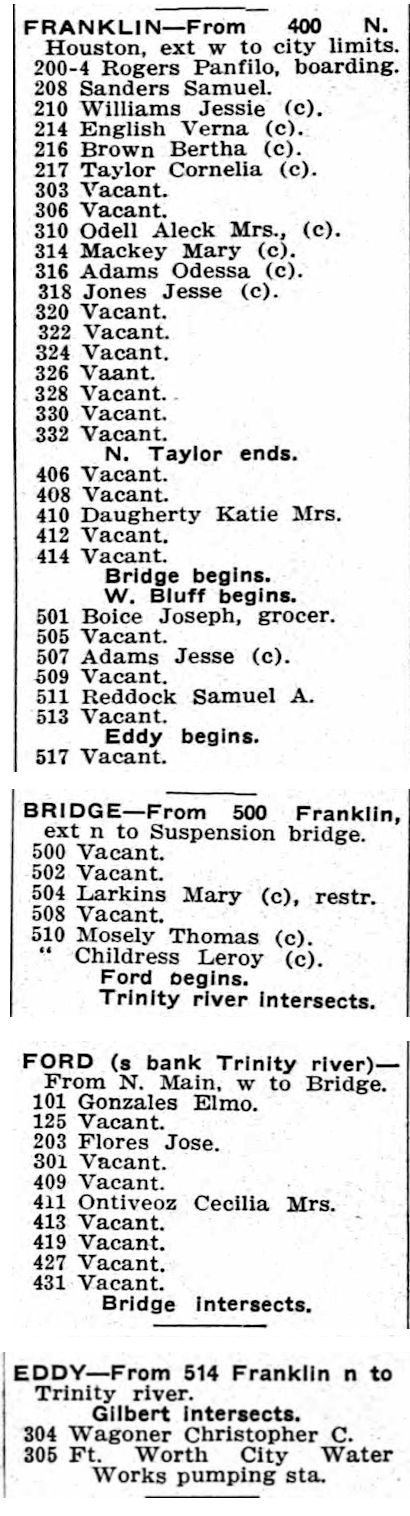

There were four streets in the Flats. Unpaved. The “main drag” was Franklin Street (blue dot), which began on the bluff at the north end of Houston Street and ran down the slope to the west, bridged the river, and became Courthouse Avenue (today’s White Settlement Road).

The other three streets were Ford (green dot), Bridge (red dot), and Eddy (yellow dot). Near where Ford Street ended at the Trinity River, in the days before bridges people used to . . . wait for it . . . ford the river there because it was shallow.

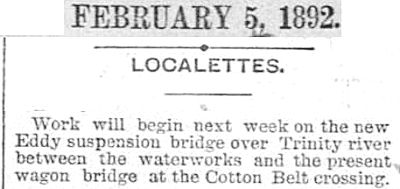

And Bridge Street led to one of the first . . . wait for it . . . bridges over the river, a wire suspension bridge (W on map) built in 1892 and designed by . . . wait for it . . . Daniel M. Eddy. The Paddock Viaduct (P) would not be built until 1914, replacing an iron bridge at that location.

And Bridge Street led to one of the first . . . wait for it . . . bridges over the river, a wire suspension bridge (W on map) built in 1892 and designed by . . . wait for it . . . Daniel M. Eddy. The Paddock Viaduct (P) would not be built until 1914, replacing an iron bridge at that location.

The heart of Battercake Flats lay between Franklin Street and the river (the area on the 1909 map not platted into city lots). Most of the homes in the heart of the Flats were not along its four streets. Who needed streets? Streets were for automobiles, streetcars, horse-drawn wagons. No one in the heart of the Flats had the money for such extravagances. Many of them did not own a pair of shoes.

The 1914 city directory lists the four streets of Battercake Flats. Note the reference to the suspension bridge.

The 1914 city directory lists the four streets of Battercake Flats. Note the reference to the suspension bridge.

Located at the confluence of the two forks of the river, Battercake Flats was the outgroup enclave most susceptible to flooding. The Flats was flooded, for example, in 1908, 1915, 1922, and 1942. The shanties of Battercake Flats didn’t just flood when the river came calling. They disintegrated (instant kindling); they floated away (instant houseboats). Battercake Flats was flooded twice in 1915. After the first flood, formaldehyde was used to disinfect houses, lime was poured on the ground, and oil was poured on stagnant water. Six weeks later, the second clip says, residents of the Flats were preparing to move to higher ground again as a surge of water approached from Lake Worth. Note the mention of Nutt Dam, which was located in the Flats just west of the Paddock Viaduct. Note that the story says that the water level over the spillway of Lake Worth was the “highest ever known.” The lake was all of two years old!

Located at the confluence of the two forks of the river, Battercake Flats was the outgroup enclave most susceptible to flooding. The Flats was flooded, for example, in 1908, 1915, 1922, and 1942. The shanties of Battercake Flats didn’t just flood when the river came calling. They disintegrated (instant kindling); they floated away (instant houseboats). Battercake Flats was flooded twice in 1915. After the first flood, formaldehyde was used to disinfect houses, lime was poured on the ground, and oil was poured on stagnant water. Six weeks later, the second clip says, residents of the Flats were preparing to move to higher ground again as a surge of water approached from Lake Worth. Note the mention of Nutt Dam, which was located in the Flats just west of the Paddock Viaduct. Note that the story says that the water level over the spillway of Lake Worth was the “highest ever known.” The lake was all of two years old!

After the 1915 flooding the Fort Worth Relief Association recommended that evacuated squatters not be allowed to return to their “squalid huts” in the Flats because of the risk of disease.

After the 1915 flooding the Fort Worth Relief Association recommended that evacuated squatters not be allowed to return to their “squalid huts” in the Flats because of the risk of disease.

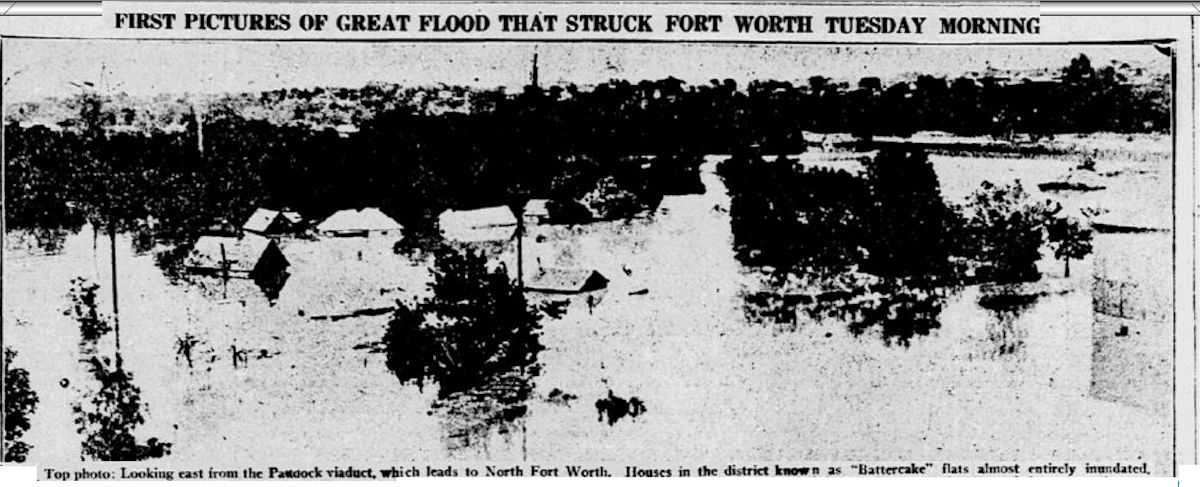

Dallas Morning News photo shows Battercake Flats from the viaduct during the flood of 1922.

Dallas Morning News photo shows Battercake Flats from the viaduct during the flood of 1922.

After the 1922 flood the city considered condemning the Flats because the enclave faced persistent flood threats and because part of the Flats near the courthouse was used as a “public dumping ground.” The Board of Health said, “This unwholesome condition was largely responsible for the great small pox epidemic in which instance twelve dead bodies were found secreted in a single room.”

After the 1922 flood the city considered condemning the Flats because the enclave faced persistent flood threats and because part of the Flats near the courthouse was used as a “public dumping ground.” The Board of Health said, “This unwholesome condition was largely responsible for the great small pox epidemic in which instance twelve dead bodies were found secreted in a single room.”

The Board of Health concluded that such a place was “a rendezvous for criminals, degenerates and undesirables” and “unfit for human habitation.”

When residents of the Flats returned to their “squalid huts” after the flood of 1922, no doubt they held their noses and scoured that public dumping ground to find materials with which to repair their homes or build new ones. Many of the homes in the Flats were Frankenshanties, built with scavenged building materials and improvisation. Discarded tarps or sheet metal panels might do for a roof; three dry-goods boxes might constitute a living room suite. Many of the homes were doorless, windowless shells without electricity, gas, or water. During cold weather, Flats residents tore down unoccupied shanties for firewood. Like the mother of seven in the Courtright clip, some people lived in tents.

The land in the Flats that contained the dumping ground was owned by R. L. Crowdus, who also owned a nearby “hide house” that imparted an “odiferous” and “obnoxious” smell to the Flats as “green” hides cured.

The Flats was not condemned in 1922, and, sure enough, it flooded again in 1942, and residents were evacuated.

The Flats was not condemned in 1922, and, sure enough, it flooded again in 1942, and residents were evacuated.

Battercake Flats’ population was mostly African Americans with a small Hispanic population and a minuscule white population. As to the name “Battercake,” battercake is another word for pancake. Thus, historian Dr. Richard Selcer in A History of Fort Worth in Black & White theorizes that “Battercake” was an unsubtle allusion to Aunt Jemima brand pancake mix. As to “Flats,” the terrain of the heart of Battercake Flats close to the river certainly was as flat as a pancake. Another theory is that “Battercake” referred to the thick layer of mud that covered the area after flooding.

Most residents of the Flats, like most residents of other outgroup enclaves, were decent people just trying to get by without much money. But many residents of the Flats were squatters living, the Star-Telegram reminded, “in the land of free rents and no taxes.” Many were low-wage unskilled laborers, migrant workers (for example, cotton pickers), unemployed or unemployable. And the Flats certainly had a criminal element: drunk-and-disorderlies, sneak thieves, armed robbers, prostitutes, people who were wanted for more serious crimes. (Enclaves made a good hideout.)

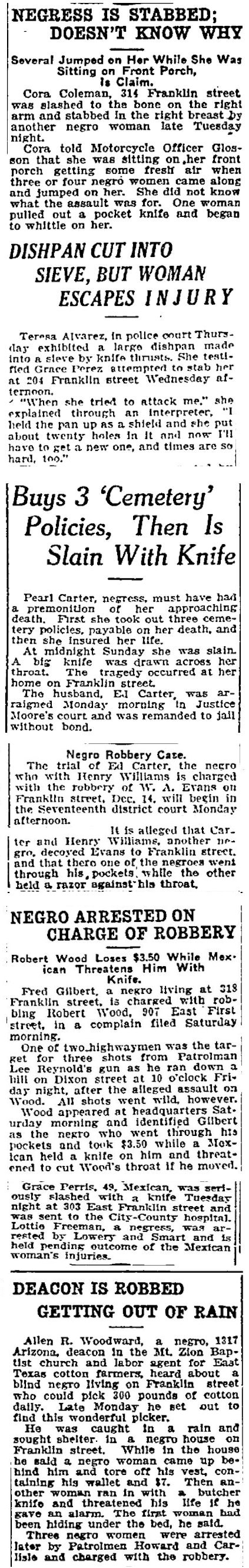

Indeed, Battercake Flats had one of the highest crime rates in the city. These clips indicate that several residents of the Flats knew their way around a blade. In the bottom clip, patrolman Howard was Pete Howard, whose beat was Battercake Flats. After Howard made that arrest on August 9, 1915 he had one more week to live.

Indeed, Battercake Flats had one of the highest crime rates in the city. These clips indicate that several residents of the Flats knew their way around a blade. In the bottom clip, patrolman Howard was Pete Howard, whose beat was Battercake Flats. After Howard made that arrest on August 9, 1915 he had one more week to live.

If the Flats was dangerous for its own residents, the Flats was even more dangerous for outsiders who ventured in. Even if those outsiders wore a badge and carried a gun. Sometimes especially if those outsiders wore a badge and carried a gun. Franklin Street was one of the meanest streets in Cowtown for a policeman.

If the Flats was dangerous for its own residents, the Flats was even more dangerous for outsiders who ventured in. Even if those outsiders wore a badge and carried a gun. Sometimes especially if those outsiders wore a badge and carried a gun. Franklin Street was one of the meanest streets in Cowtown for a policeman.

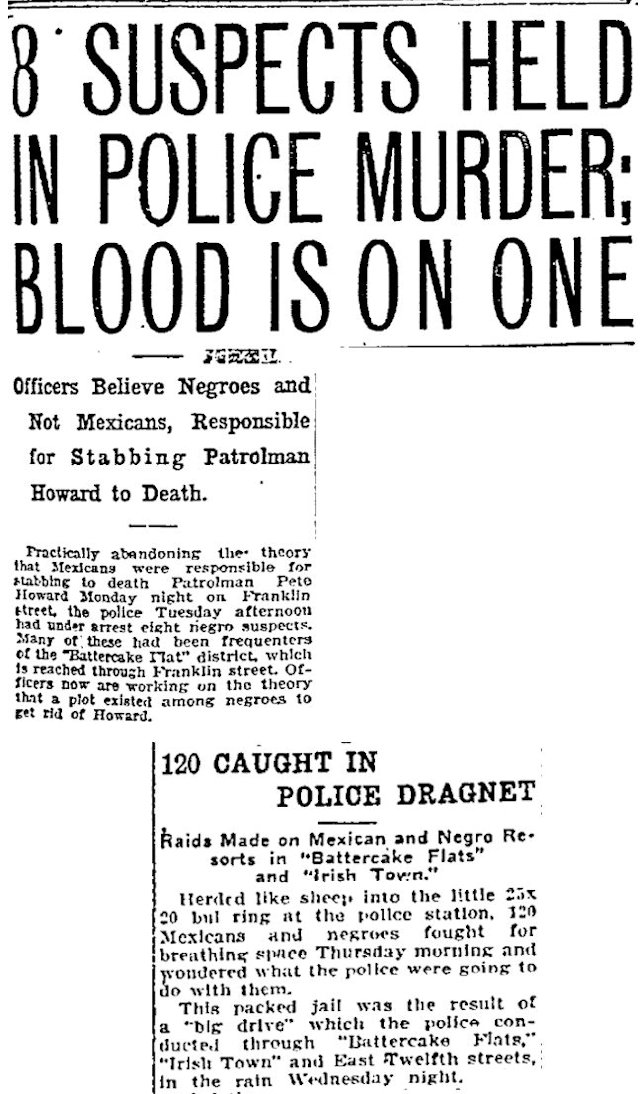

On Franklin Street on the night of August 16, 1915 two men fatally stabbed patrolman Pete Howard. Police at first sought their suspects among the Hispanic population but quickly switched to the African-American population. Just to hedge their bets, police conducting a dragnet of “resorts” in Battercake Flats and Irish Town rounded up 120 people both brown and black.

Ultimately police would determine that two men—Luis Flores and Jose Estapa—killed officer Howard. Flores would receive a life sentence.

(Irish Town, located east of downtown, had formed as an Irish enclave but evolved into an African-American enclave as the eastern edge of downtown became the center of African-American life in Fort Worth.)

After Howard’s murder Police Chief Cullen Bailey announced that Battercake Flats would be patrolled by a pair of officers.

![]() Howard’s name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

Howard’s name is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

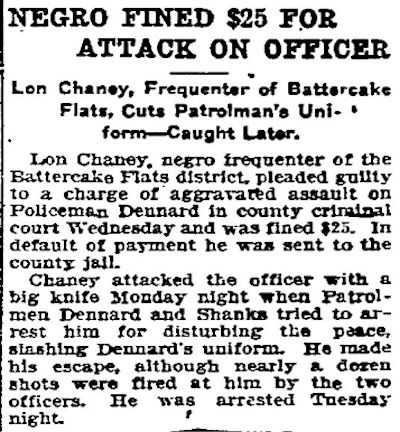

Three months after officer Howard was killed, officer Dennard was stabbed in the Flats while patrolling with officer Shanks.

Three months after officer Howard was killed, officer Dennard was stabbed in the Flats while patrolling with officer Shanks.

One of the Flats’ less-deadly “police characters” was Alice Odell, who owned a rooming house at 310 Franklin Street. In an enclave in which African Americans were the majority, Alice was a minority: She was white. Alice took time out from exchanging vows of matrimony to get into all kinds of mischief. In these clips from the years 1914-1916 Alice was arrested for abusive language, drunkenness, arson, and theft. In the bottom clip note that Alice escaped from jail courtesy of Bessie Williams. More about Bessie later.

One of the Flats’ less-deadly “police characters” was Alice Odell, who owned a rooming house at 310 Franklin Street. In an enclave in which African Americans were the majority, Alice was a minority: She was white. Alice took time out from exchanging vows of matrimony to get into all kinds of mischief. In these clips from the years 1914-1916 Alice was arrested for abusive language, drunkenness, arson, and theft. In the bottom clip note that Alice escaped from jail courtesy of Bessie Williams. More about Bessie later.

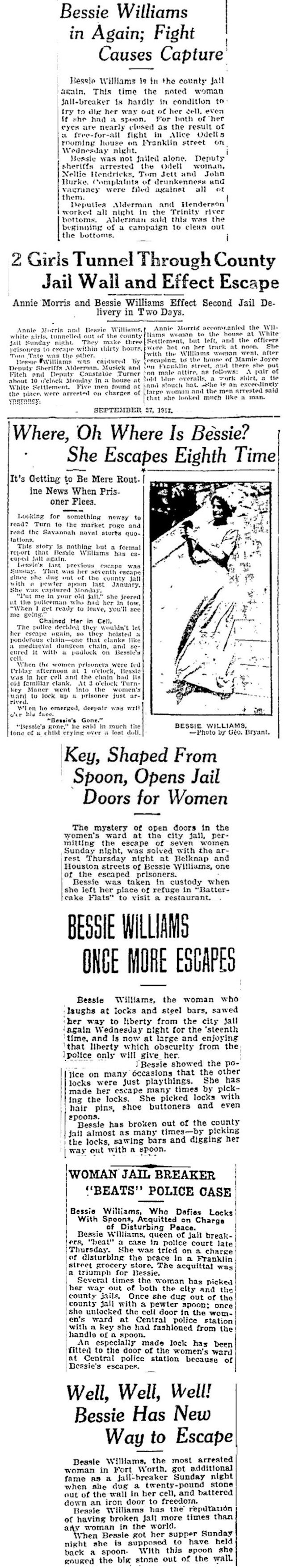

Unlike Alice Odell, who ran a rooming house, Bessie Williams was a squatter in the Flats. But like Alice, Bessie was white. And like Alice, Bessie was routinely arrested, usually for “theft from person,” receiving and concealing stolen goods, drunkenness, and vagrancy, which was an umbrella term that included prostitution. Bessie was a prostitute “under 20 years of age” whom the Star-Telegram called “the most arrested woman in Fort Worth.”

Unlike Alice Odell, who ran a rooming house, Bessie Williams was a squatter in the Flats. But like Alice, Bessie was white. And like Alice, Bessie was routinely arrested, usually for “theft from person,” receiving and concealing stolen goods, drunkenness, and vagrancy, which was an umbrella term that included prostitution. Bessie was a prostitute “under 20 years of age” whom the Star-Telegram called “the most arrested woman in Fort Worth.”

In the top clip note that Bessie Williams and Alice Odell were arrested after a “free-for-all fight” at Alice’s rooming house in Battercake Flats. The Flats may have been squalid and dangerous, but to its residents it also was home, and Bessie Williams was one Flats resident who couldn’t bear to be away from home. Just as routinely as Bessie was arrested, Bessie just as routinely broke out of jail, both city and county. Bessie Williams was self-paroling. Her “get out of jail free” tool of choice was a spoon. She used a spoon either to dig with or to shape into a key to unlock her cell door. These clips from the years 1912-1915 show that Bessie broke out of jail more times than the police—or even Bessie herself—could count in order to get back to the Flats. Where she was again arrested. Only to escape again. Only to be arrested again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

In the top clip note that Bessie Williams and Alice Odell were arrested after a “free-for-all fight” at Alice’s rooming house in Battercake Flats. The Flats may have been squalid and dangerous, but to its residents it also was home, and Bessie Williams was one Flats resident who couldn’t bear to be away from home. Just as routinely as Bessie was arrested, Bessie just as routinely broke out of jail, both city and county. Bessie Williams was self-paroling. Her “get out of jail free” tool of choice was a spoon. She used a spoon either to dig with or to shape into a key to unlock her cell door. These clips from the years 1912-1915 show that Bessie broke out of jail more times than the police—or even Bessie herself—could count in order to get back to the Flats. Where she was again arrested. Only to escape again. Only to be arrested again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

(The county jail that couldn’t hold Bessie had been built in 1884. By 1912 people were calling for a new jail in part because of Bessie and her spoon.)

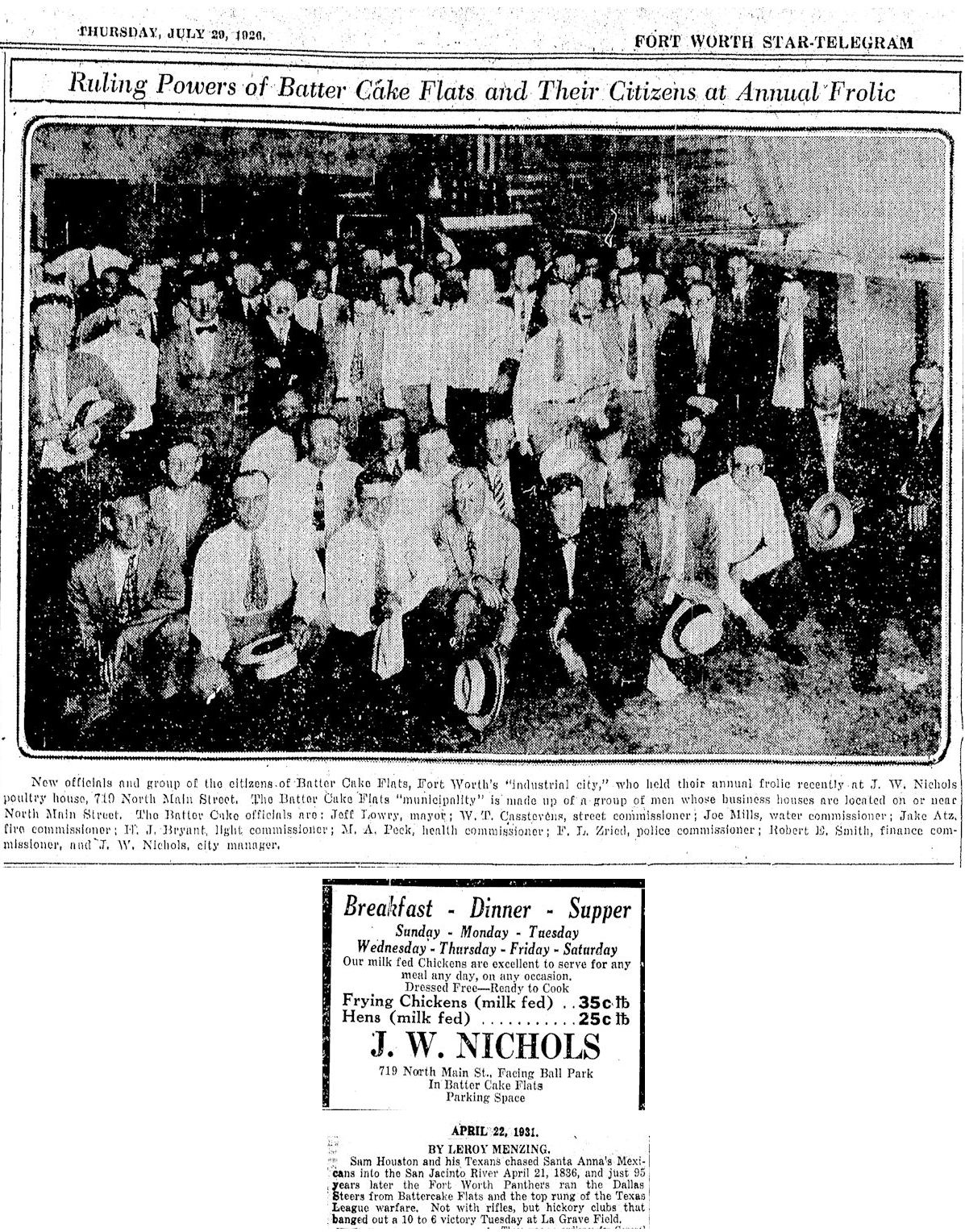

Oddly, some people applied the term Battercake Flats to the area of north Fort Worth from the river north to the Ku Klux Klan klavern at 1012 North Main. That area included the power plant, Panther Park on the west side of North Main Street, and, after 1926, LaGrave Field, home of the Fort Worth Panthers (Cats) baseball team. But Battercake north and Battercake south had little in common beyond the name.

Oddly, some people applied the term Battercake Flats to the area of north Fort Worth from the river north to the Ku Klux Klan klavern at 1012 North Main. That area included the power plant, Panther Park on the west side of North Main Street, and, after 1926, LaGrave Field, home of the Fort Worth Panthers (Cats) baseball team. But Battercake north and Battercake south had little in common beyond the name.

In the mid-1920s, perhaps to shed the negative connotation of the term Battercake Flats, the area north of the river unofficially was renamed “Industrial City” (complete with unofficial city officials) as business leaders in that area campaigned to develop the area commercially.

North or south of the river, Battercake Flats is gone now, like all the other enclaves of a century ago. Urban renewal removed some slums. Freeways displaced others. By the 1920s the population of Battercake Flats was becoming more Hispanic than African American and came to be known as the barrio “La Corte.” The barrio was displaced, in part, by the Trinity River floodway as the Army Corps of Engineers straightened, deepened, and widened the river and built levees. The floodway rendered the river bottom land relatively safe from flooding. Suddenly La Corte real estate became commercially valuable. Squatters were evicted.

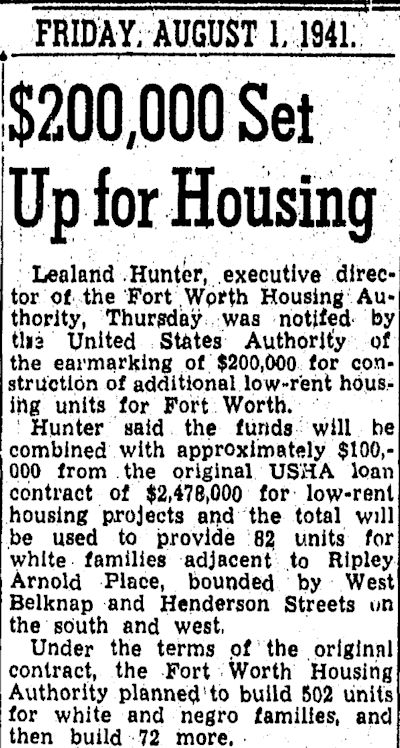

In 1941 the federal government built Ripley Arnold Place public housing project on the area of the barrio just north of West Belknap Street, where the Tarrant County College Trinity River campus now sits. The low-income African Americans and later low-income Hispanics were displaced by Ripley Arnold Place’s low-income whites.

In 1941 the federal government built Ripley Arnold Place public housing project on the area of the barrio just north of West Belknap Street, where the Tarrant County College Trinity River campus now sits. The low-income African Americans and later low-income Hispanics were displaced by Ripley Arnold Place’s low-income whites.

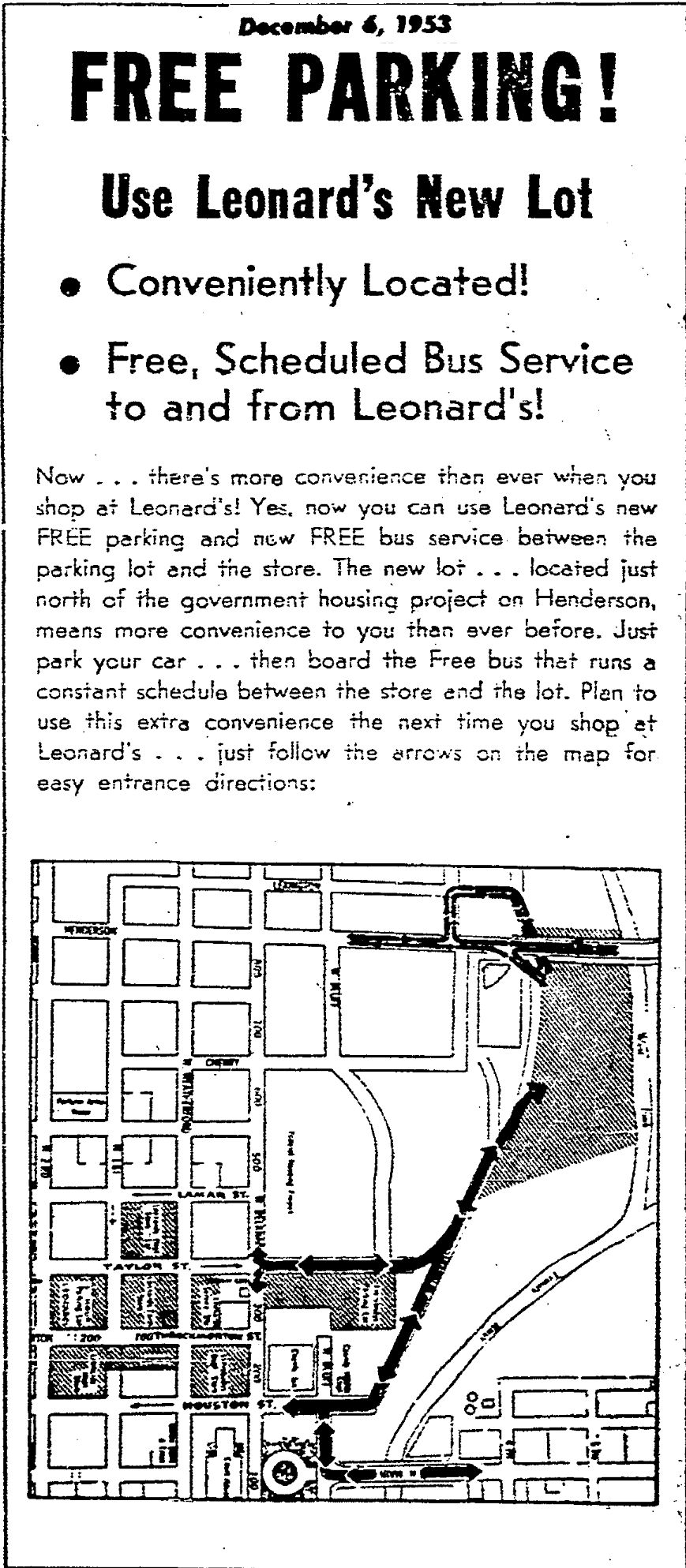

In 1953 the sprawling parking lot of Leonard’s Department Store covered the west end of the barrio. The Leonard’s shuttle buses ran along what was left of Franklin Street, once the main drag of Battercake Flats.

In 1953 the sprawling parking lot of Leonard’s Department Store covered the west end of the barrio. The Leonard’s shuttle buses ran along what was left of Franklin Street, once the main drag of Battercake Flats.

What’s in a Name? From Bum’s Bowery to Hogan’s Alley

This Star-Telegram story from 1923 gives the names and locations of several outgroup enclaves in Fort Worth.

This Star-Telegram story from 1923 gives the names and locations of several outgroup enclaves in Fort Worth.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for the tip.)

Las Reliquias (Part 1): Casa de la Corte and the Last Man on Franklin Street

I was looking at one of the above photos and the name J W Nichols rang a bell. I can remember one of my school book covers from the early 70s having a JW Nichols advertisement. Also I remember going with my mom to pick up chicken for dinner at Nichols place. Seems I remember the store near the east side of Oakwood cemetery off north main. Great article Mike.

Thanks, Keith. I think J.W. Nichols was on North Houston back when the street still had railroad tracks down it leading to the old electric plant.

Check the FWST for June 30, 1916. The article is titled, “Last of Jameses, Citizen of Fort Worth, Anxious to Swear Allegiance to U.S.”

Its a great story!

Boy, is it! I drove right past where his house was on Stella Street at Riverside Drive just yesterday. He worked at Hub Furniture just a couple of blocks from where he lived. Thanks for the tip.