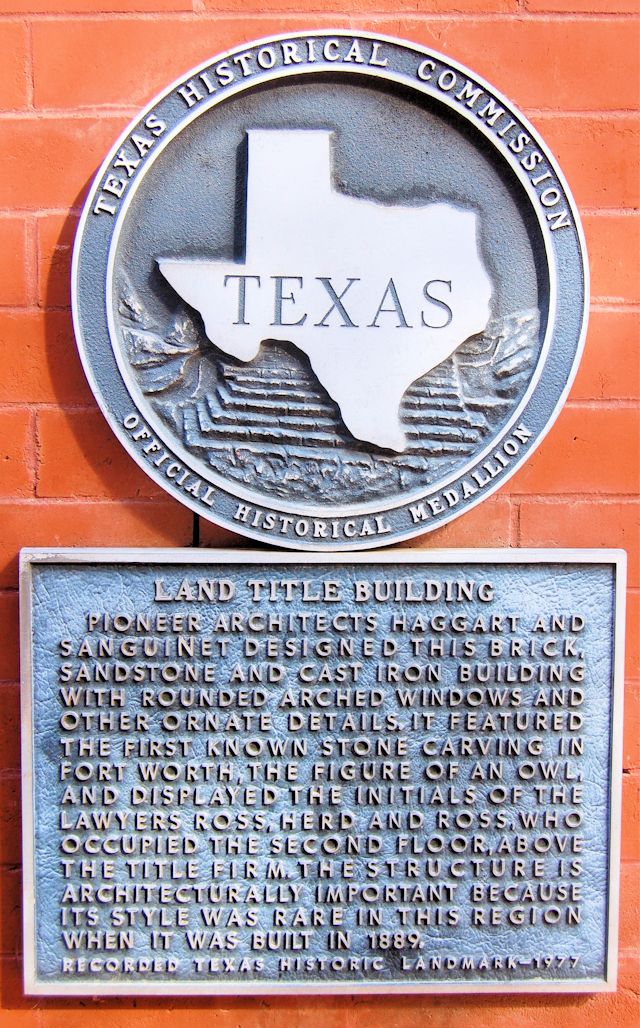

Inch for inch, brick for brick, and flourish for flourish, the Land Title Block Building on East 4th Street downtown surely is our finest nineteenth-century commercial building. With this little red jewel box, architects Marshall Sanguinet (1859-1936) and Samuel Bertine Haggart (1832-1921) remind us that there was a polished facet to rough-and-tumble frontier Fort Worth.

While rowdy cowhands were shooting up saloons in Hell’s Half Acre, and violence between Native Americans and white settlers lingered on in the nineteenth century, Sanguinet and Haggart were designing an elegant building of brick, sandstone, and iron that we still use in the twenty-first century.

While rowdy cowhands were shooting up saloons in Hell’s Half Acre, and violence between Native Americans and white settlers lingered on in the nineteenth century, Sanguinet and Haggart were designing an elegant building of brick, sandstone, and iron that we still use in the twenty-first century.

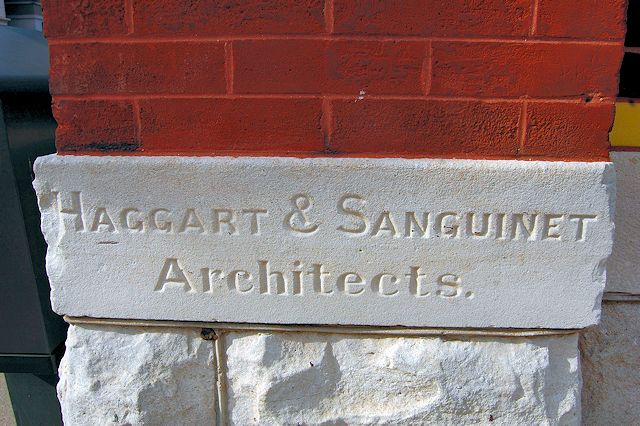

Haggart got top billing on the cornerstone, but much less is known about Haggart than about Sanguinet. Haggart had practiced in New York City and New Orleans in the 1870s before coming to Fort Worth in the 1880s to open a solo practice initially. At the time, Sanguinet’s partner was Alonzo Dawson. Then Sanguinet and Haggart partnered briefly, teaming to design the Natatorium, which opened in 1890 at the north end of the block, and Fort Worth High School (1890). After they dissolved their partnership in 1889 or 1890, Haggart had a solo practice and then partnered with son Walter; Sanguinet partnered with the Messer brothers and then, of course, with Carl Staats.

Haggart got top billing on the cornerstone, but much less is known about Haggart than about Sanguinet. Haggart had practiced in New York City and New Orleans in the 1870s before coming to Fort Worth in the 1880s to open a solo practice initially. At the time, Sanguinet’s partner was Alonzo Dawson. Then Sanguinet and Haggart partnered briefly, teaming to design the Natatorium, which opened in 1890 at the north end of the block, and Fort Worth High School (1890). After they dissolved their partnership in 1889 or 1890, Haggart had a solo practice and then partnered with son Walter; Sanguinet partnered with the Messer brothers and then, of course, with Carl Staats.

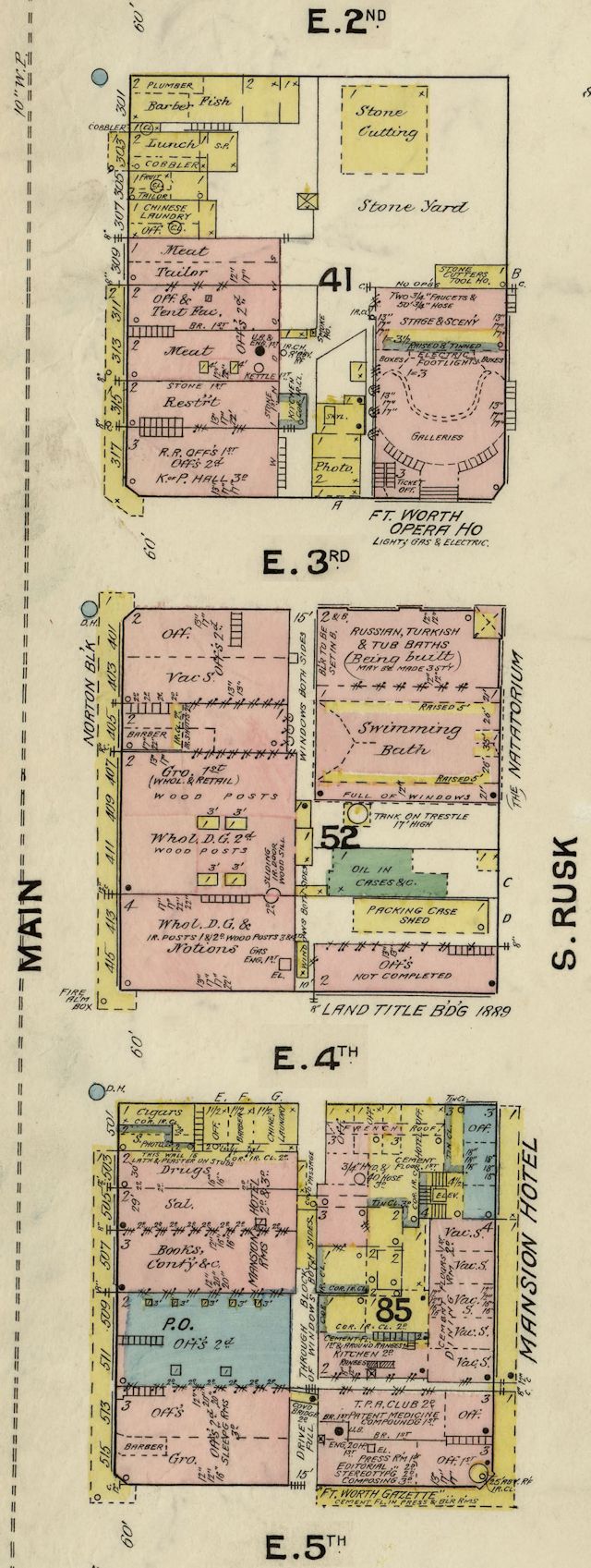

In 1889 most of the buildings downtown were one or two stories high. Some banks and hotels were three or four stories high. The Board of Trade building, also completed in 1889, was five stories high with a seven-story tower.

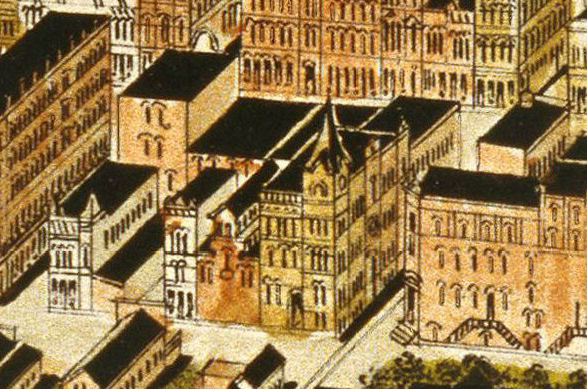

This 1891 bird’s-eye-view map shows the Land Title Block Building along 4th Street on the left and the Natatorium along 3rd street on the right. Across 3rd Street is the Fort Worth Opera House (1883).

This 1891 bird’s-eye-view map shows the Land Title Block Building along 4th Street on the left and the Natatorium along 3rd street on the right. Across 3rd Street is the Fort Worth Opera House (1883).

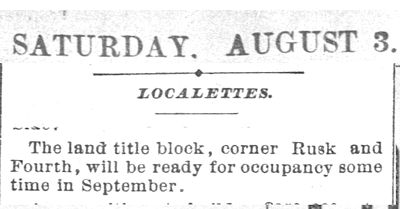

On August 3, 1889 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that the building was almost finished. (Rusk Street is now Commerce Street.) The building opened just two years after Luke Short shot Jim Courtright three blocks away, just one year after the cornerstone was laid for St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and just two months after the first season of the Texas Spring Palace exhibition closed.

On August 3, 1889 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that the building was almost finished. (Rusk Street is now Commerce Street.) The building opened just two years after Luke Short shot Jim Courtright three blocks away, just one year after the cornerstone was laid for St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and just two months after the first season of the Texas Spring Palace exhibition closed.

Original tenants of the building were the law firm of Ross, Herd & Ross (later Ross, Chapman & Ross), Land Mortgage Bank, and Chamberlin Investment Company. That means this little building is closely tied to the development of Arlington Heights.

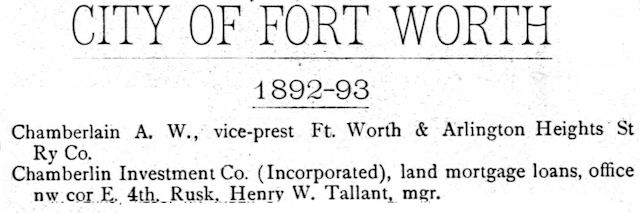

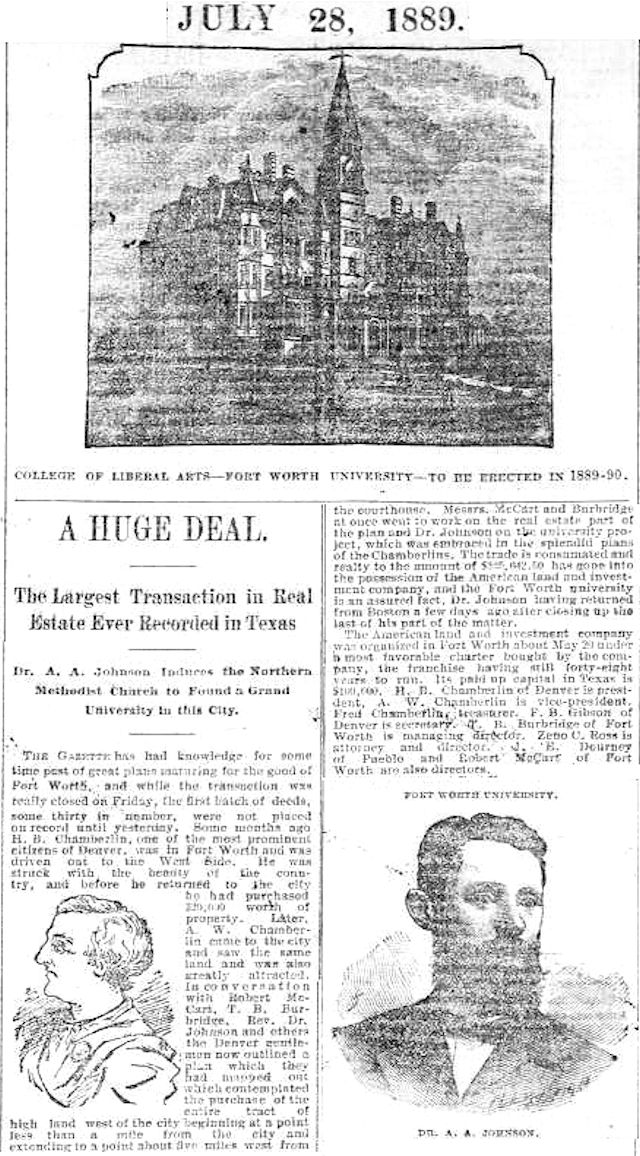

In fact, just as the Land Title Block Building was being completed, Humphrey Chamberlin, a British-born Denver developer, was announcing for Fort Worth plans for what the Gazette called, hyperbolically, “the largest transaction in real estate ever recorded in Texas.” But Chamberlin did indeed have three grand plans: 1. to develop the area west of Fort Worth residentially as “Arlington Heights” and link it to Fort Worth with his Fort Worth and Arlington Heights Street Railway, 2. to build a grand hotel for Arlington Heights, and 3. to relocate Texas Wesleyan College, which had just been rechartered as “Fort Worth University,” from the near South Side to a new campus in Arlington Heights. Part of Arlington Heights was even platted as “University Heights.”

Note that among the directors of Chamberlin’s company were Zeno Ross of Ross, Herd & Ross and attorney Robert McCart. McCart owned hundreds of acres where Arlington Heights would be developed. (McCart, for whom McCart Avenue is named, had signed the bond for Luke Short after the Courtright shooting in 1887 and in 1890 would help sort out the sordidness of Mayor Pendleton’s overlapping marriages.)

Well, Chamberlin plans 1 and 2 eventually came about, even if the hotel, Ye Arlington Inn, burned in 1894. But plan 3 never came about, and Fort Worth University stayed right where it was.

Some views of the little red jewel box:

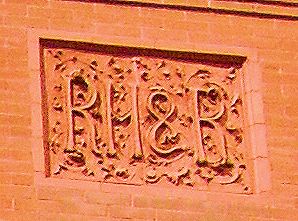

In the upper right corner of the front facade can be seen the initials “RH&R” for “Ross, Herd & Ross.”

In the upper right corner of the front facade can be seen the initials “RH&R” for “Ross, Herd & Ross.”

In 1889, when the Land Title Block Building opened, Victoria was still queen of England. Elsewhere that year, the Eiffel Tower opened, Charlie Chaplin was born, the Coca-Cola company incorporated, and the Oklahoma land rush of April 22 populated a large part of the territory overnight.

First-story window has an I-beam steel lintel with florets. Second-story window pilasters probably are cast iron.

First-story window has an I-beam steel lintel with florets. Second-story window pilasters probably are cast iron.

Cornice with dentil molding.

Cornice with dentil molding.

Today the Land Title Block Building houses an eatery aptly named the “Bird Cafe.” Note the two birds in the bas-relief on the east wall:

And the bird on the stair post:

And the bird on the stair post:

The bird’s-eye-view drawing looks like medieval Europe.

Indeed it does. I have seen those from 1876, 1886, and 1891 for Fort Worth. Wish I could have watched them being drawn.

I saw a few hoot owls. Great photo work, Mike. It’s amazing these great buildings survive. What with the ongoing “improvement craze.” Buildings this old might have ghosts hanging around.

Thanks, Earl. Great little building.

Those aren’t just any old ‘birds’ … They are the Wise Owls ! … Hoot, Hoot !

I think people of Greek extraction would nod knowingly at “flying saucer” in 1889, though they might prefer full size flying plates.

Duck!