For much of the year 1912 newspaper readers around the country followed a human-interest story that had it all: romance, religion, two-by-fours.

And yet the story of Addison John Roe, Jenny Henry Scranton, and Gorham Tufts began, as most complicated stories do, quite simply.

You may not have heard of A. J. Roe, but if you had lived in Fort Worth at the beginning of the twentieth century you would have heard of him. In fact, you might have lived or worked in a house or apartment or office building built with his lumber.

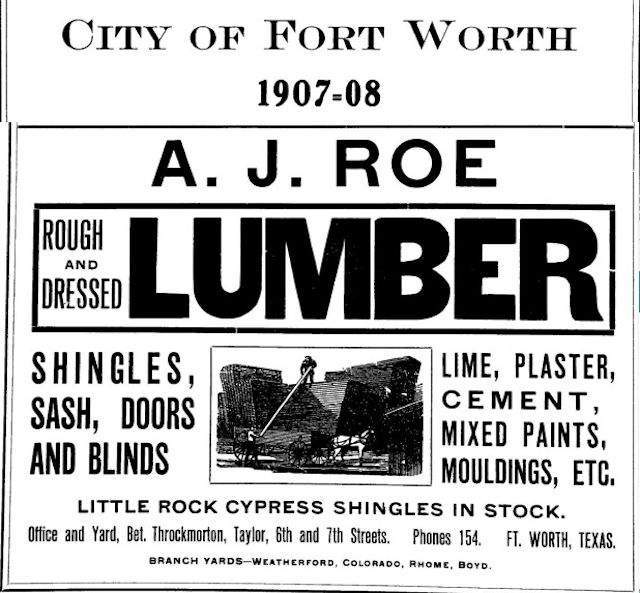

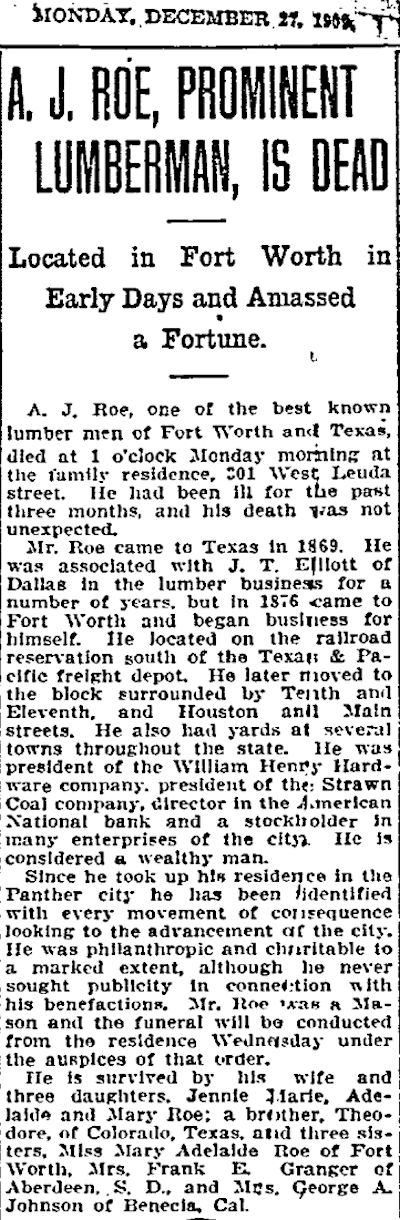

A. J. Roe, born in New York State, had come to Texas in 1869. By 1876 he was in Fort Worth, where he opened a lumberyard. He prospered. He would own lumberyards in several Texas cities, real estate in several Texas counties, be president of a coal company and a hardware company and a director of American National Bank.

A. J. Roe, born in New York State, had come to Texas in 1869. By 1876 he was in Fort Worth, where he opened a lumberyard. He prospered. He would own lumberyards in several Texas cities, real estate in several Texas counties, be president of a coal company and a hardware company and a director of American National Bank.

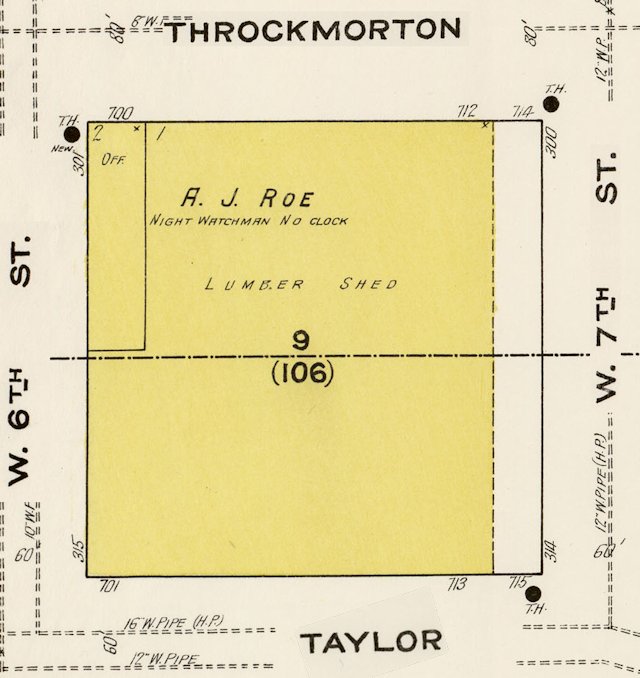

Roe’s Fort Worth lumberyard covered an entire city block downtown, bounded by West 6th and West 7th streets and Throckmorton and Taylor streets. That block alone constituted a fortune: In 1912 the Star-Telegram would write that the block, one of the last downtown blocks owned by one person, might be worth as much as $300,000 ($7.5 million today).

Roe’s Fort Worth lumberyard covered an entire city block downtown, bounded by West 6th and West 7th streets and Throckmorton and Taylor streets. That block alone constituted a fortune: In 1912 the Star-Telegram would write that the block, one of the last downtown blocks owned by one person, might be worth as much as $300,000 ($7.5 million today).

Roe’s lumberyard was where the killer of County Attorney Jefferson Davis McLean was cornered and shot by police in 1907. Later the Fort Worth Club and the Worth Hotel and Worth Theater would be built on the “Roe block.”

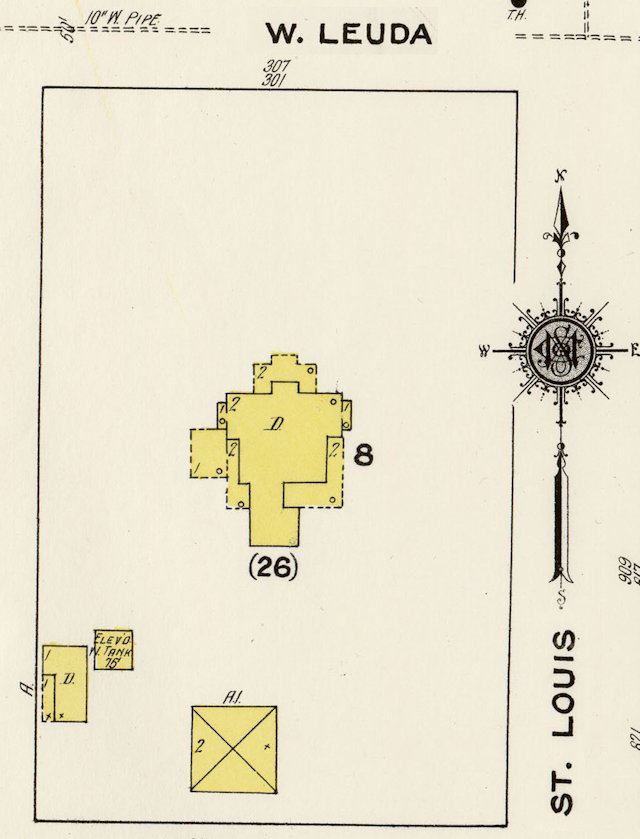

Like his lumberyard, Roe’s residential property encompassed a city block at Leuda and St. Louis streets on the near South Side. Living across the street at 300 and 312 West Leuda were George B. Monnig Jr. and William Monnig, respectively.

Like his lumberyard, Roe’s residential property encompassed a city block at Leuda and St. Louis streets on the near South Side. Living across the street at 300 and 312 West Leuda were George B. Monnig Jr. and William Monnig, respectively.

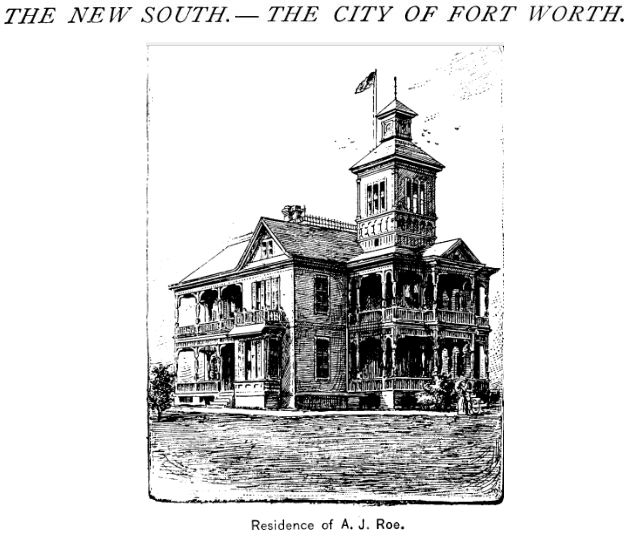

Roe’s house was included in a feature on Fort Worth in New England Magazine in 1891.

Roe’s house was included in a feature on Fort Worth in New England Magazine in 1891.

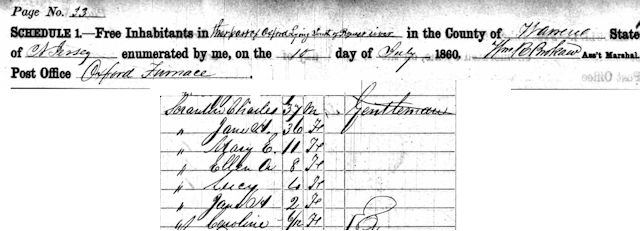

Jenny Henry Scranton was, like A. J. Roe, from back east. She was born in New Jersey in 1857. Her father in the 1860 census listed his occupation as “gentleman.” Jenny was listed as “Jane,” which was also her mother’s name.

Jenny Henry Scranton was, like A. J. Roe, from back east. She was born in New Jersey in 1857. Her father in the 1860 census listed his occupation as “gentleman.” Jenny was listed as “Jane,” which was also her mother’s name.

About 1887 these two easterners—A. J. and Jenny—got married out west in Cowtown. It was a May-December marriage: A. J. Roe was fifty-three; Jenny was thirty.

The new century found A. J. and Jenny financially well-to-do and the parents of three daughters.

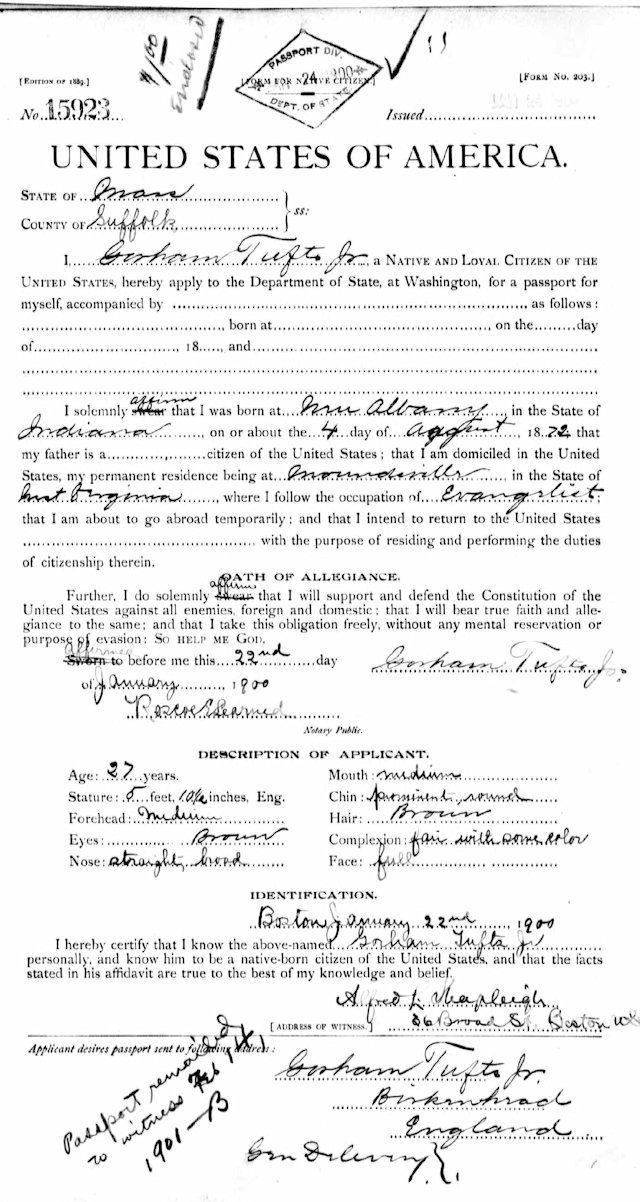

The new century found Gorham Tufts, another easterner, preparing to go overseas as an “evangelist.” Gorham Tufts was born in Indiana in 1872, was living in Moundsville, West Virginia in 1900.

The new century found Gorham Tufts, another easterner, preparing to go overseas as an “evangelist.” Gorham Tufts was born in Indiana in 1872, was living in Moundsville, West Virginia in 1900.

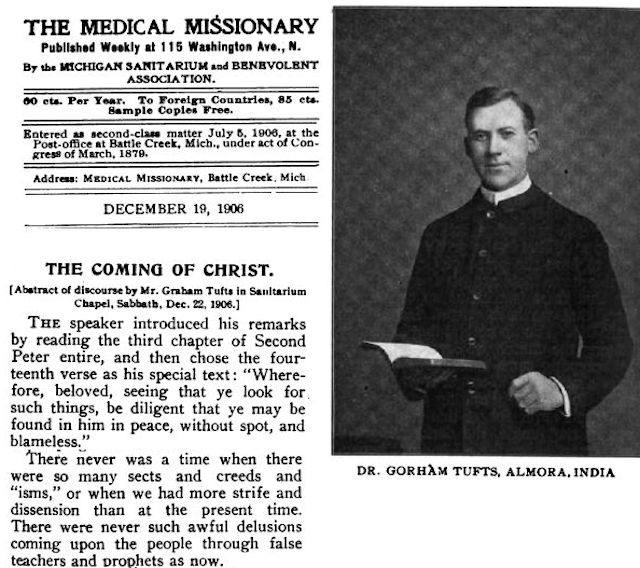

By 1901 Tufts was in India, where he opened a Bible school in Calcutta. In 1906 the journal Medical Missionary published an abstract of a speech given by Tufts, who told of his experiences as a missionary in India. Note that Tufts bemoaned “sects” and “isms” and “false teachers and prophets.”

By 1901 Tufts was in India, where he opened a Bible school in Calcutta. In 1906 the journal Medical Missionary published an abstract of a speech given by Tufts, who told of his experiences as a missionary in India. Note that Tufts bemoaned “sects” and “isms” and “false teachers and prophets.”

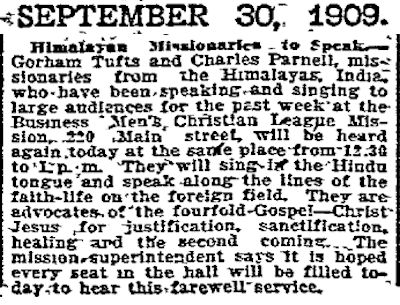

By September 1909 our three easterners were like three planets whose orbits are drawing inexorably closer to each other: Himalayan missionary Gorham Tufts was now out west and just thirty miles from A. J. and Jenny as Tufts spoke in Dallas at the Business Men’s Christian League Mission. Tufts was accompanied by fellow missionary Charles Parnell, whom we will meet again.

By September 1909 our three easterners were like three planets whose orbits are drawing inexorably closer to each other: Himalayan missionary Gorham Tufts was now out west and just thirty miles from A. J. and Jenny as Tufts spoke in Dallas at the Business Men’s Christian League Mission. Tufts was accompanied by fellow missionary Charles Parnell, whom we will meet again.

Three months later, on December 27, 1909, Addison John Roe, by then a millionaire, died. Jenny Henry Scranton Roe was now a millionaire widow.

Three months later, on December 27, 1909, Addison John Roe, by then a millionaire, died. Jenny Henry Scranton Roe was now a millionaire widow.

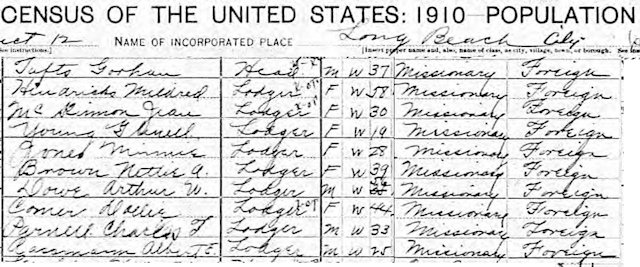

By 1910 Gorham Tufts was living in Long Beach, California, where he had nine lodgers (including Charles Parnell and six women), all listed as “missionaries.”

By 1910 Gorham Tufts was living in Long Beach, California, where he had nine lodgers (including Charles Parnell and six women), all listed as “missionaries.”

Meanwhile, the widow Roe, who had long been a worker in the Christian Science Church in Fort Worth, attended a Christian Science convention in California. There she met Gorham Tufts, who was not a member of that denomination but rather was the founder of his own denomination, which he called the “Church of God” but which the Dallas Morning News called a “Hindu psychical cult.”

The millionaire lumber heiress Jenny Roe and Gorham Tufts were married in Los Angeles on April 19, 1911. This was Jenny’s second May-December marriage, but this time Jenny was December: She was fifty-four; Tufts was thirty-nine.

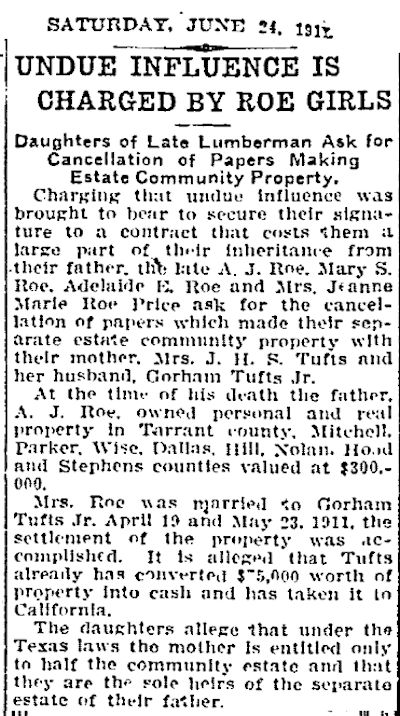

And lo, it came to pass that the Reverend Tufts did begin to perform the religious ritual of laying on of hands, except that in the case of Gorham Tufts, he was mostly laying his hands on the money of other people. Thirty-four days after the wedding, Tufts had persuaded the three Roe daughters to sign papers making their separate inheritance community property with their mother and their new stepfather. In June the daughters accused Roe of using undue influence and claimed he had already converted some Roe estate assets into $75,000 cash ($1.9 million today) and had spirited all those shekels to sunny California.

And lo, it came to pass that the Reverend Tufts did begin to perform the religious ritual of laying on of hands, except that in the case of Gorham Tufts, he was mostly laying his hands on the money of other people. Thirty-four days after the wedding, Tufts had persuaded the three Roe daughters to sign papers making their separate inheritance community property with their mother and their new stepfather. In June the daughters accused Roe of using undue influence and claimed he had already converted some Roe estate assets into $75,000 cash ($1.9 million today) and had spirited all those shekels to sunny California.

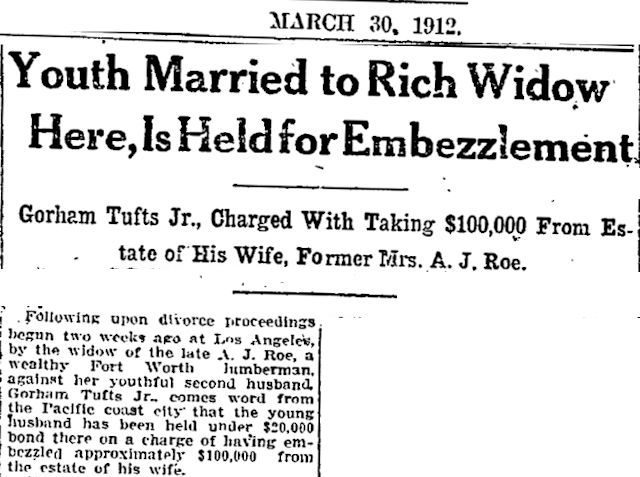

Then came the year 1912. And for Gorman Tufts, the shekels hit the fan. By March his new bride had revoked all powers of attorney granted to him and had filed for divorce. Tufts was in jail in Los Angeles, charged with embezzling $100,000 ($2.4 million today) from his December bride.

Then came the year 1912. And for Gorman Tufts, the shekels hit the fan. By March his new bride had revoked all powers of attorney granted to him and had filed for divorce. Tufts was in jail in Los Angeles, charged with embezzling $100,000 ($2.4 million today) from his December bride.

Then, as Tufts sat in his jail cell, unable to post his $20,000 bond, he suffered another plague of bad news: On April 10 several women who had been members of Tufts’s missionary band in India said they had lost “property, attire, money and jewels as a result of their trust in Tufts.” A grand jury was “investigating Tufts’ financial transactions in connection with his alleged missionary efforts.”

Then, as Tufts sat in his jail cell, unable to post his $20,000 bond, he suffered another plague of bad news: On April 10 several women who had been members of Tufts’s missionary band in India said they had lost “property, attire, money and jewels as a result of their trust in Tufts.” A grand jury was “investigating Tufts’ financial transactions in connection with his alleged missionary efforts.”

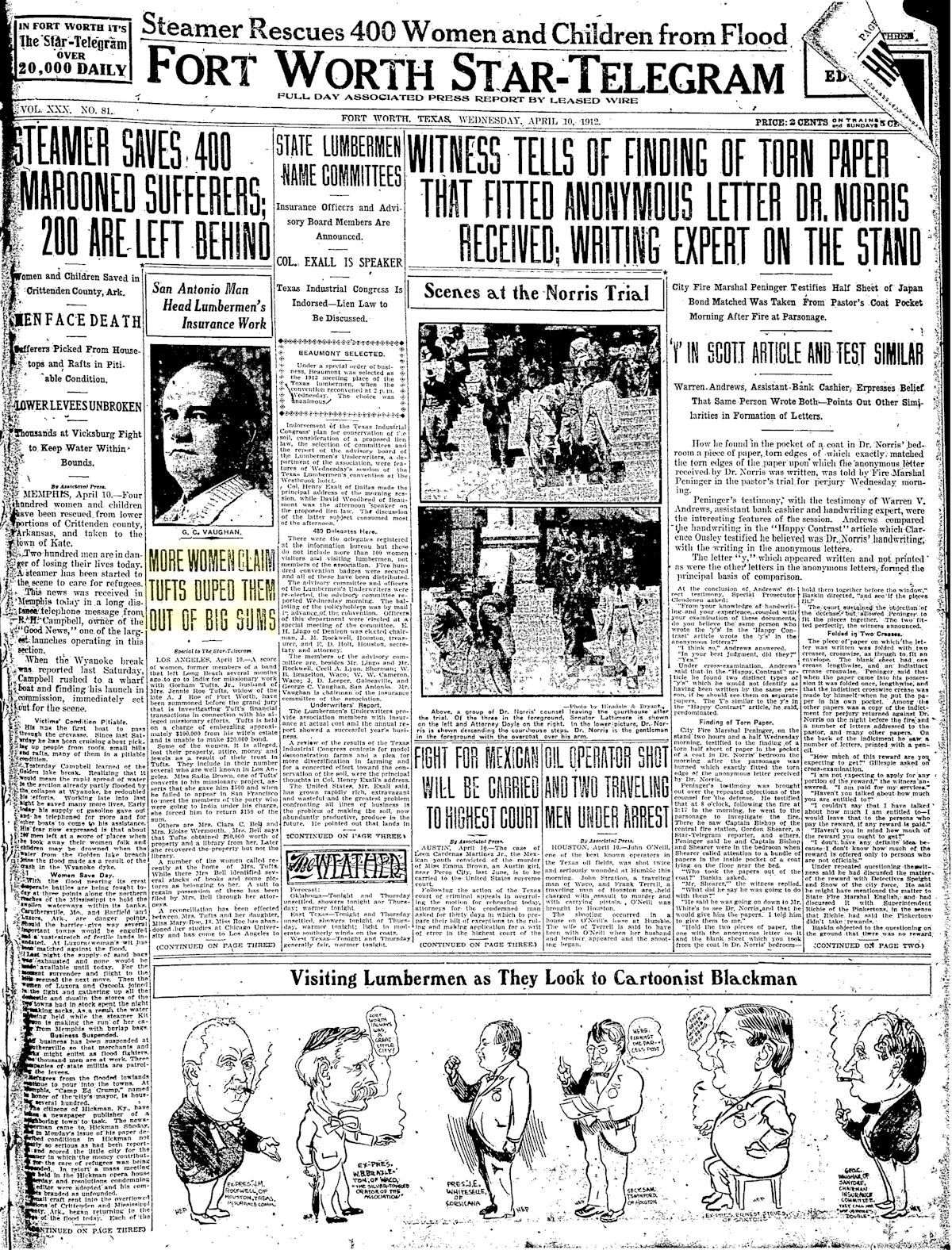

That day in April Tufts shared the front page with another man of the cloth as the perjury trial of J. Frank Norris of First Baptist Church continued after the church building was destroyed by fire.

That day in April Tufts shared the front page with another man of the cloth as the perjury trial of J. Frank Norris of First Baptist Church continued after the church building was destroyed by fire.

April is the cruelest month, T. S. Eliot wrote, and April of 1912 had one more cruelty to inflict upon Gorham Tufts: Enter the other Mrs. Gorham Tufts.

April is the cruelest month, T. S. Eliot wrote, and April of 1912 had one more cruelty to inflict upon Gorham Tufts: Enter the other Mrs. Gorham Tufts.

Say what?

Yes, there was a first Mrs. Tufts, and she was in town and hankerin’ to tag-team with the second Mrs. Tufts in a grudge match against the Love God.

“Love God”?

All is revealed in Part 2: Confessions of a Love God: “Let Us Prey” (Part 2)