These days residential real estate developers often give streets random names to evoke pastoral visions—such as “Silver Creek Avenue” (even though there is not a precious metal or a stream within miles) or “Misty Meadow Boulevard” (even though there is no precipitation or grassland within miles)—or to support the equally random name of a subdivision (such as “Round Table Terrace” and “Lancelot Lane” in a subdivision named “Camelot Estates”).

These days residential real estate developers often give streets random names to evoke pastoral visions—such as “Silver Creek Avenue” (even though there is not a precious metal or a stream within miles) or “Misty Meadow Boulevard” (even though there is no precipitation or grassland within miles)—or to support the equally random name of a subdivision (such as “Round Table Terrace” and “Lancelot Lane” in a subdivision named “Camelot Estates”).

But in earlier times street names had some logic behind them. For example, streets often were named for a prominent person. Several north-south streets downtown from Henderson east to Jones were named for figures from Texas and American history. Likewise John Peter Smith, Daggett, Jarvis, and Hulen streets are self-explanatory. Lancaster Avenue is named for John L. Lancaster, whose Texas & Pacific railroad in the early 1930s transformed his namesake street with a new passenger terminal, a new freight terminal, and three new underpasses. Or streets were named for a destination. For example, Belknap Street led to Fort Belknap in Young County. Camp Bowie Boulevard led to . . . wait for it . . . Camp Bowie.

On the other hand, sometimes a subdivision developer or a sales agent gave himself a little immortality by naming a street after himself, as in Clarke and Bunting avenues in Hi Mount or Sargent Street in Beacon Hill or Bailey Avenue in William J. Bailey’s Bailey addition on the near West Side.

And sometimes streets were named for the relatives of the developer. And so it was with five streets on the near South Side. They are named for the wife and five daughters of a man who didn’t even live in Fort Worth but whose story is one of great triumph and tragedy in early Texas.

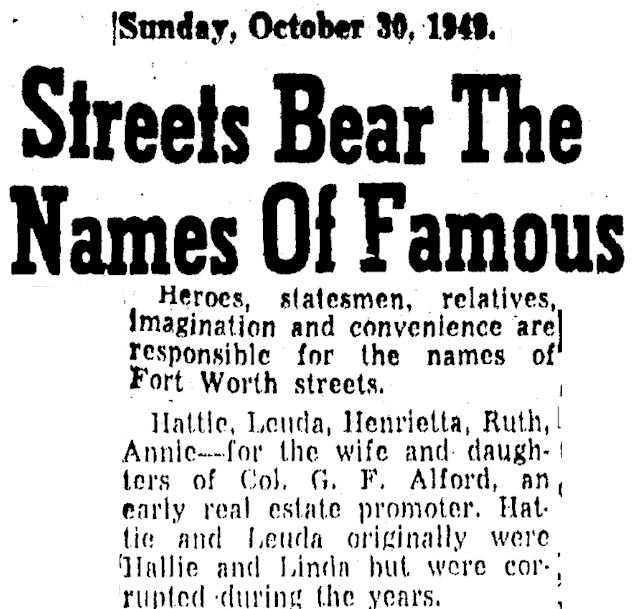

In 1949 the edition of the Star-Telegram celebrating the centennial of Fort Worth said that five streets in the Alford & Veal’s addition were named for the wife and daughters of G. F. Alford: wife Annie and daughters Annie, Henrietta, Ruth, Hallie, and Linda. The newspaper pointed out that the names of Hattie and Leuda streets are corruptions of the names of Alford daughters Hallie and Linda.

In 1949 the edition of the Star-Telegram celebrating the centennial of Fort Worth said that five streets in the Alford & Veal’s addition were named for the wife and daughters of G. F. Alford: wife Annie and daughters Annie, Henrietta, Ruth, Hallie, and Linda. The newspaper pointed out that the names of Hattie and Leuda streets are corruptions of the names of Alford daughters Hallie and Linda.

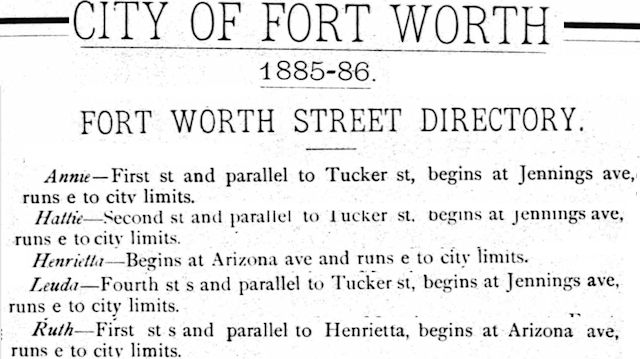

Indeed, by the time the five namesake streets appeared in the 1885 city directory, “Linda” and “Hallie” had become “Leuda” and “Hattie.”

Indeed, by the time the five namesake streets appeared in the 1885 city directory, “Linda” and “Hallie” had become “Leuda” and “Hattie.”

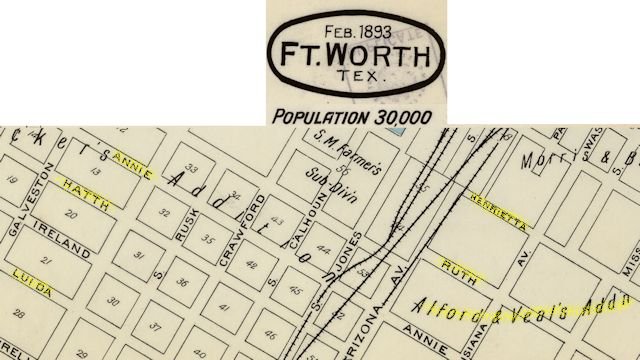

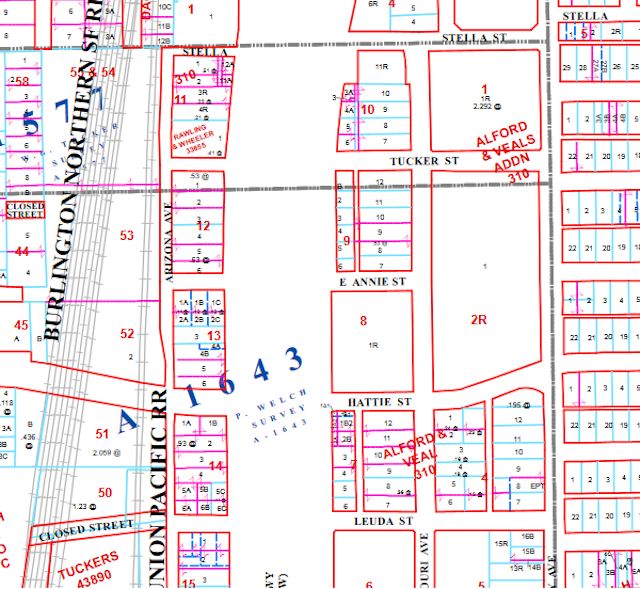

This 1893 Sanborn map shows the five Alford namesake streets. Of the five, Annie Street does double duty, named for both Alford’s wife and a daughter. (Ruth’s first name was “Stella,” and Stella Street is just two blocks north of the former Ruth Street, but Stella Street is not in the Alford & Veal’s addition, so I am afraid to assume that it, too, was named for daughter Stella Ruth.)

This 1893 Sanborn map shows the five Alford namesake streets. Of the five, Annie Street does double duty, named for both Alford’s wife and a daughter. (Ruth’s first name was “Stella,” and Stella Street is just two blocks north of the former Ruth Street, but Stella Street is not in the Alford & Veal’s addition, so I am afraid to assume that it, too, was named for daughter Stella Ruth.)

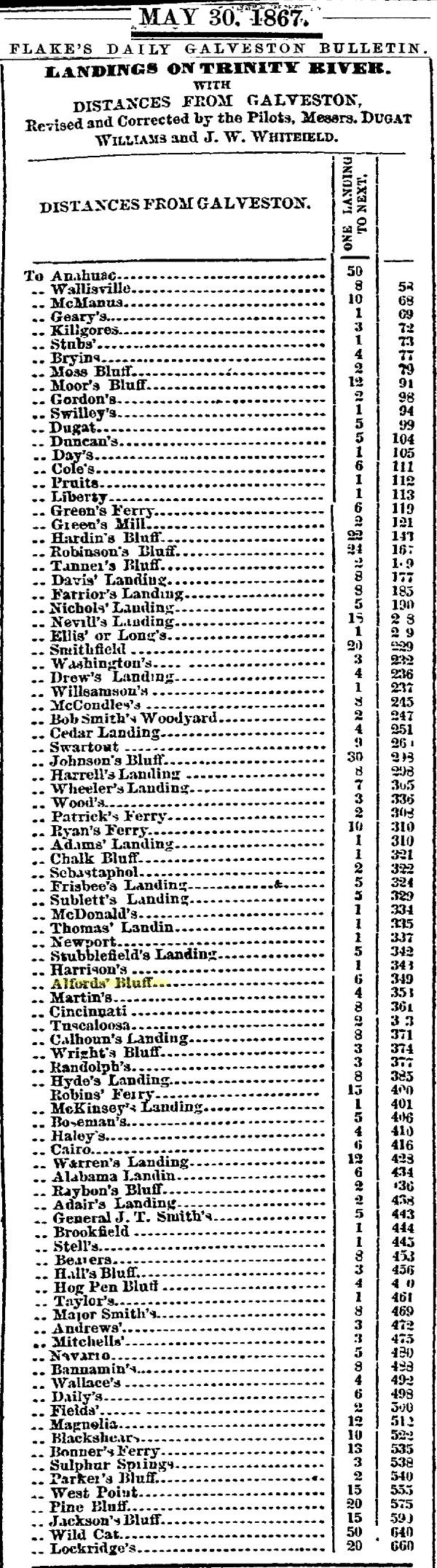

Some history: Confederate General George Frederick Alford was the son of Colonel George G. Alford, who had fought under Winfield Scott in the War of 1812 and under Sam Houston in the Texas Revolution of 1836. George Frederick was born the next year in New Madrid, Missouri, but the family soon moved to Texas, and George Frederick spent his early childhood on Alford’s Bluff, the family’s plantation and steamboat landing on the Trinity River in Trinity County.

Alford’s Bluff was 349 river miles upstream from Galveston but still 311 river miles from the northernmost landing at Lockridge’s Bluff in Navarro County, which was another 226 river miles from Dallas.

Alford’s Bluff was 349 river miles upstream from Galveston but still 311 river miles from the northernmost landing at Lockridge’s Bluff in Navarro County, which was another 226 river miles from Dallas.

In 1847, when George was ten, his parents died, and he returned to New Madrid to live with an aunt. But he soon became restless and ran away from home. According to Biographical History of Dallas County, for three years young George lived with “semi-savage Indian tribes of the far western lands,” learning their ways. Then he struck out once again—on foot—traveling to the promised land of California, a trip that took six months. In the town of Shasta he was appointed deputy court clerk. In 1857, when he had saved enough money, he returned to New Madrid to marry Annie Maulsby, a former schoolmate. In 1859 the couple moved to Alford’s Bluff on the Trinity River.

There Alford became, the Star-Telegram would write in 1903, “one of the wealthiest cattlemen, planters and slaveowners of Texas.”

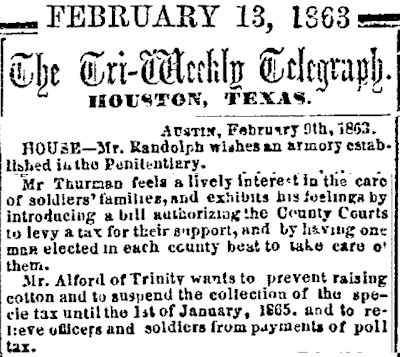

With money comes influence. In 1859 Alford was elected to the Texas legislature.

With money comes influence. In 1859 Alford was elected to the Texas legislature.

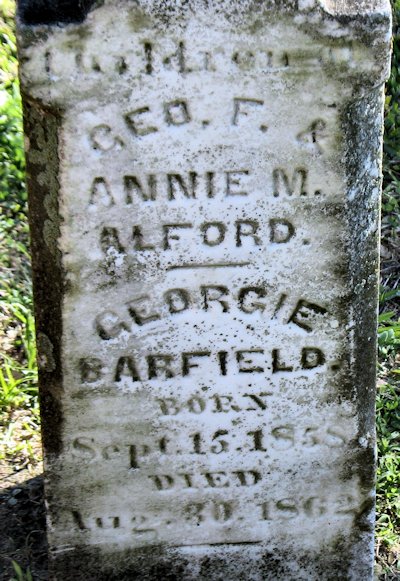

Yes, George Frederick Alford knew great fortune. But he also knew great loss. George and Annie Maulsby Alford would have ten children. At least four of six daughters, including Georgie Barfield in 1862, would die before their fourth birthday.

Yes, George Frederick Alford knew great fortune. But he also knew great loss. George and Annie Maulsby Alford would have ten children. At least four of six daughters, including Georgie Barfield in 1862, would die before their fourth birthday.

After the Civil War began, Alford fought for the Confederacy, taking part in the Battle of Mansfield and the Battle of Pleasant Hill in Louisiana in 1864.

After the war Alford was again elected to the Texas legislature in 1865. But soon afterward a flood of the Trinity River put his plantation under twelve feet of water, washing away most of his fortune.

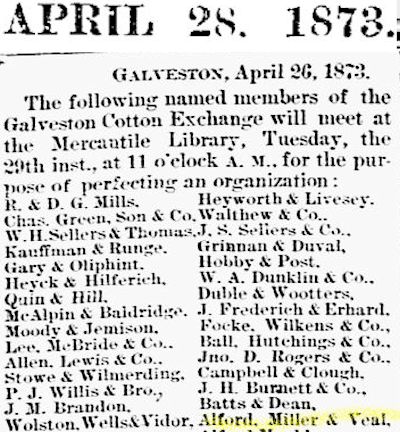

In 1866 Alford resigned from the legislature and moved from Alford’s Bluff to Galveston, where he remade his fortune in cotton, groceries, banking, and foreign exchange. He and William G. Veal, with whom Alford would develop the Alford & Veal’s addition in Fort Worth, were members of the Galveston Cotton Exchange.

In 1866 Alford resigned from the legislature and moved from Alford’s Bluff to Galveston, where he remade his fortune in cotton, groceries, banking, and foreign exchange. He and William G. Veal, with whom Alford would develop the Alford & Veal’s addition in Fort Worth, were members of the Galveston Cotton Exchange.

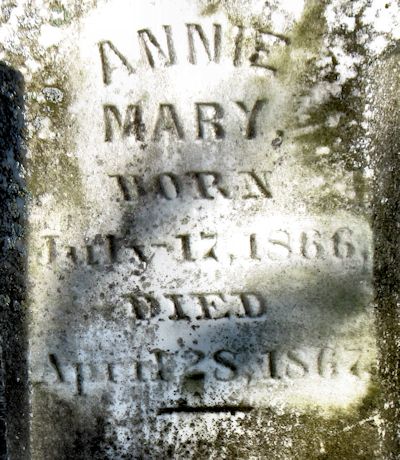

In 1867 the first of the five sisters of the South Side died. Daughter Annie Mary Alford died in Galveston. She is buried in Old Galveston Cemetery.

In 1867 the first of the five sisters of the South Side died. Daughter Annie Mary Alford died in Galveston. She is buried in Old Galveston Cemetery.

Then came the financial panic of 1873—the same panic that delayed by three years the arrival of the railroad in Fort Worth. George Frederick Alford lost his second fortune.

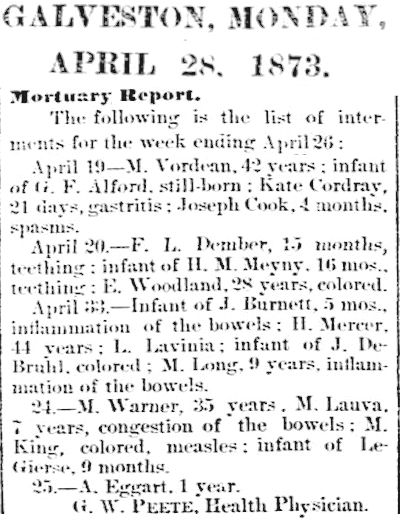

The year 1873 brought another loss—emotional, not financial. The Alford infant who was stillborn in 1873 may have been daughter Mary George Alford, who, records show, was born and died that year. Of seventeen people listed in the Galveston weekly mortuary report, eleven were one year old or younger.

The year 1873 brought another loss—emotional, not financial. The Alford infant who was stillborn in 1873 may have been daughter Mary George Alford, who, records show, was born and died that year. Of seventeen people listed in the Galveston weekly mortuary report, eleven were one year old or younger.

After the panic of 1873, by 1875 Alford found himself $400,000 ($8.7 million today) in debt.

But the year 1875 was not done. That year Alford suffered still another loss. Daughter Stella Ruth died in Galveston before her first birthday. She, too, is buried in Old Galveston Cemetery.

But the year 1875 was not done. That year Alford suffered still another loss. Daughter Stella Ruth died in Galveston before her first birthday. She, too, is buried in Old Galveston Cemetery.

In 1877, with three children buried in the local cemetery, Alford moved his family from Galveston to Dallas, where he remade his second fortune in real estate, banking, and railroads in Texas and in silver and lead mining in Mexico. It took him nine years, but he repaid his debtors one hundred cents on the dollar.

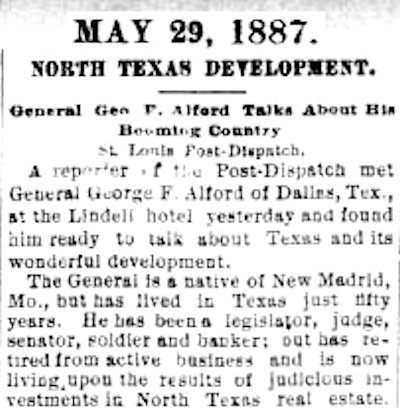

An 1887 article mentions Alford’s “judicious investments in North Texas real estate.”

An 1887 article mentions Alford’s “judicious investments in North Texas real estate.”

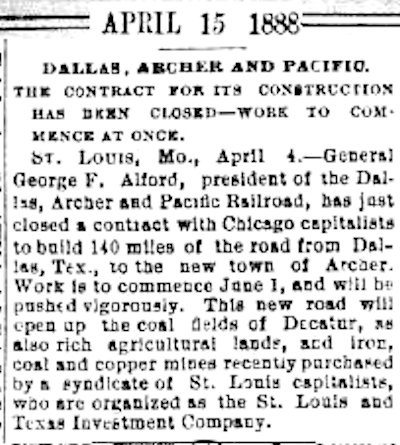

Alford also was president of the Dallas, Archer and Pacific railroad.

Alford also was president of the Dallas, Archer and Pacific railroad.

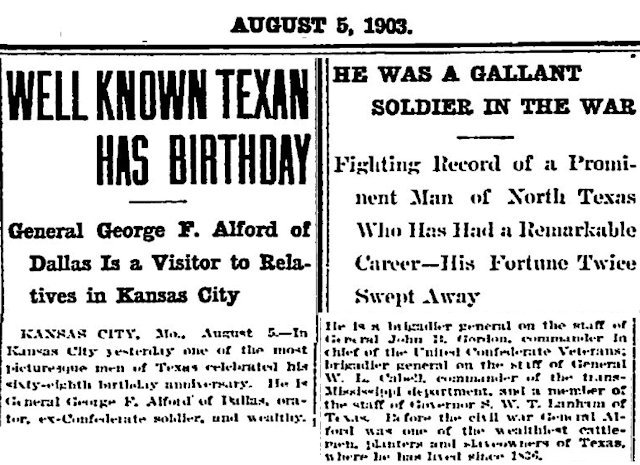

In 1903 the sixty-eighth birthday of the “well-known Texan” was news even in Kansas City.

In 1903 the sixty-eighth birthday of the “well-known Texan” was news even in Kansas City.

That year Successful American magazine wrote: “General George F. Alford of Dallas, Texas, still wears a Confederate uniform. He has never taken it off since he put it on in the early ’60s. He is much observed on the streets.”

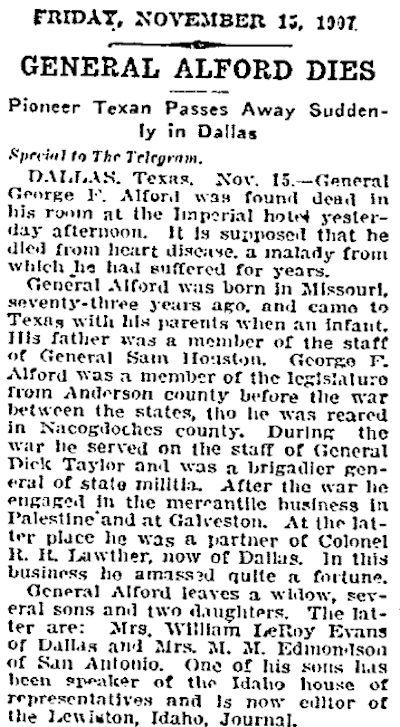

General Alford died in 1907. His obituary says he was survived by two daughters. They were the two sisters whose namesake streets are misspelled:

General Alford died in 1907. His obituary says he was survived by two daughters. They were the two sisters whose namesake streets are misspelled:

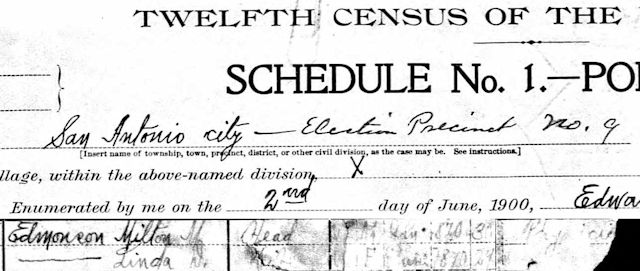

Linda Alford Edmonson (Leuda Street) was the wife of Dr. Milton Edmonson. She is buried in Missouri, where her parents were born.

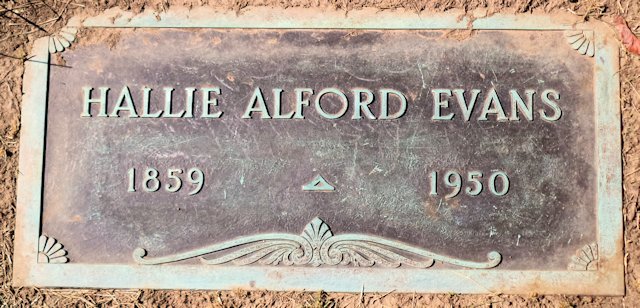

Hallie Alford Evans (Hattie Street) died in Minneapolis and is buried there.

Hallie Alford Evans (Hattie Street) died in Minneapolis and is buried there.

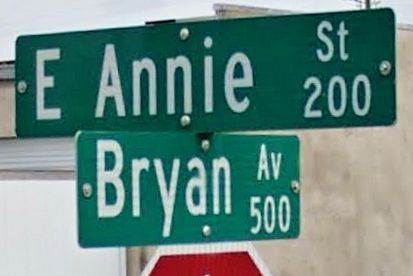

Today on the near South Side, of course, the Alford family would not recognize their namesake addition and streets. The railroads and South Freeway wiped out some streets in the Alford & Veal’s addition. Some streets have lost their identities in mergers with other streets. Only Annie, Leuda (Linda), and Hattie (Hallie) streets survive. Ruth Street is now “Tucker Street”; Henrietta Street is now “Bessie Street.” (In 1922 Fort Worth annexed several outlying areas, resulting in duplication of street names, so many street names were changed.)

Today on the near South Side, of course, the Alford family would not recognize their namesake addition and streets. The railroads and South Freeway wiped out some streets in the Alford & Veal’s addition. Some streets have lost their identities in mergers with other streets. Only Annie, Leuda (Linda), and Hattie (Hallie) streets survive. Ruth Street is now “Tucker Street”; Henrietta Street is now “Bessie Street.” (In 1922 Fort Worth annexed several outlying areas, resulting in duplication of street names, so many street names were changed.)

I could find no biographical information on Henrietta Alford, the fifth of the Alford & Veal’s addition’s five sisters of the South Side.

General George Frederick Alford, who won so much and lost so much in early Texas, is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Dallas. (All headstone photos from Find A Grave.)

General George Frederick Alford, who won so much and lost so much in early Texas, is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Dallas. (All headstone photos from Find A Grave.)

Dear Hometown by Handlebar: 02/17/2022 — Thank you for your local Ft. Worth TX history insights into the Alford and Veal’s Addition and the naming of some of the streets in that addition being named after the given names of some of the George Frederick Alford family members. Your timeline gives me a better overall picture of my distant Alford cousins’ sojourn in Texas. G. F. Alford was a son of George G. Alford ( 1793-1847 ) who served as quartermaster for Gen. Sam Houston, and both, among others, are recognized founders of the Republic of Texas. George G’s father, also a George Alford ( 1763-1852 )-year of death may have been earlier- also had military experience and was a longtime town Marshall for Monroe, Michigan, where he is buried.

One of George F. Alford’s sisters, Mary Barfield Alford, married Judge John Earle Cravens. One of their children, Mary Pauline Cravens married Benjamin Franklin Fortson. Their son, Ben Cravens Forton, is the grandfather of Ben Johnson Fortson, married to Kay Kimble Carter.

Perry, thanks for adding those names to the Alford lineage. Remarkable family.

are you related to the general and annie?

they had a son allen born 1871 who was the first husband of my great aunt grace and father of their daughter grace allen was not a good man I figure that is why he is never mentioned in any family info served in san quentin and missouri state prisons for forgery!!! died st.louis,mo he never divorced my greataunt just left her and daughter and got on with life!! I have proof to all of this.but several times george his father is mentioned as civil war hero!!

No relation. I just blog about Fort Worth history. There is an Allen Street a few blocks south of these streets, but so far I have not found any part of Allen Street to be in Alford & Veal’s addition.

Can you tell if the original address has always been 722 Missouri or could it have been 715 E Leuda St as that is where the water bill is addressed.

Larry, it may be that the main entrance was changed from the Missouri side to the Leuda side, changing the billing address. I based my searches on the Missouri address. I find nothing for 715 E. Leuda in the S-T except a furniture store in 1914.

Thank you sooooo much for your help.

Glad to help.

This information is very helpful in that the building that stands at the corner of Leuda and Missouri will now become Basecom Inc.’s general offices. I am having difficulty finding out the history of that building that was built in 1950. Could you shed some light as to what the building was before it was Fred Clark Felt Company? Thank you

Mr. Olivas, I didn’t find much. TAD says the building was built in 1950, but in 1946 a building permit was issued for a “store remodeling job” at 722 Missouri. The 1945, 1947, and 1949 city directories list 722 Missouri as Sweet Mattress Company. No city directories with that street listing are available for 1950-1952. In 1953 the address was M P Manufacturing (upholstery fabrics). In 1968 it was M-P Enterprises (manufacturers of cotton felt).