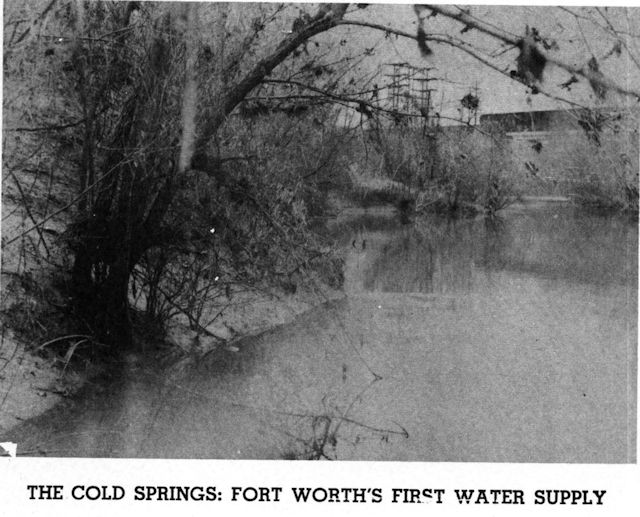

In the nineteenth century, in the days before indoor plumbing, public drinking fountains, and Sparkletts, safe drinking water was among the natural resources most precious to travelers and settlers on the frontier.

Springs were one source of such water. And one spring in particular played a role in Fort Worth history from the git-go.

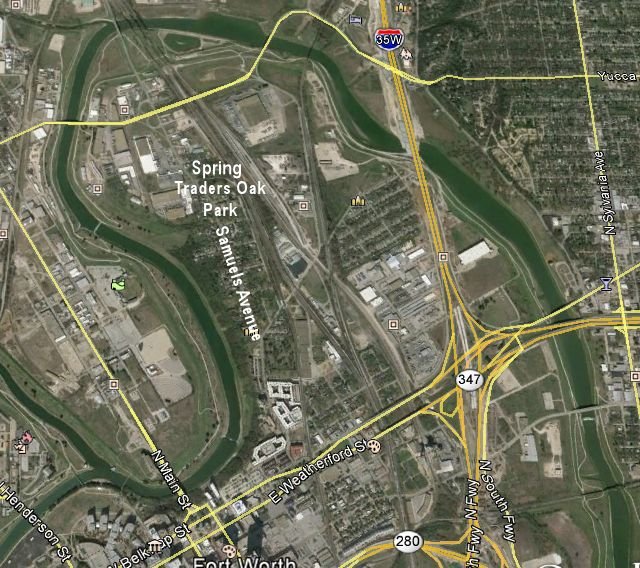

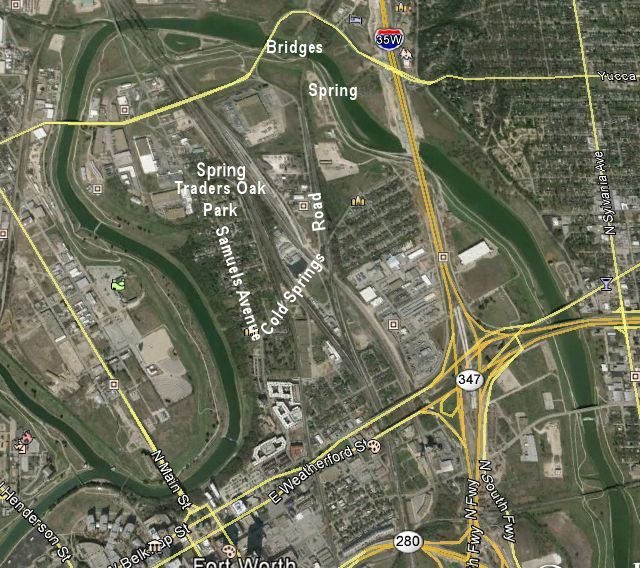

The spring was called “the Cold Springs,” and it was located northeast of today’s downtown in the “peninsula” of the Samuels Avenue area that is formed by a deep, mile-wide horseshoe bend of the Trinity River.

European and African travelers and settlers were not the first to drink from the Cold Springs, of course. Naive Americans had long known of its cool, clear water and had camped there.

Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson, an early landowner in the areas of today’s downtown and Samuels Avenue, apparently also knew about the Cold Springs in 1849 as he led Major Ripley Arnold and a few of Arnold’s Second Dragoons to the Trinity River to scout a suitable site for an Army outpost to protect white settlers on the frontier.

The Trinity River in those days was shallow, narrow, convoluted, and sluggish. It, like other local streams, could stop flowing and become stagnant during hot, dry spells. So, when Major Arnold’s soldiers built the fort on the bluff in the summer of 1849 the Cold Springs was their first source of drinking water until they dug wells such as Frenchman’s Well at the fort.

As settlers began to homestead around the fort, drawn by the protection it offered, they, too, drew water from the spring. The spring—and its surrounding grove of live oak trees—was an oasis and naturally evolved into a gathering place.

In 1849 Archibald Franklin Leonard and Henry Clay Daggett opened a trading post nearby. In 1850 settlers of the area voted in the new county’s first election nearby.

Picnics and holiday celebrations were held at the spring.

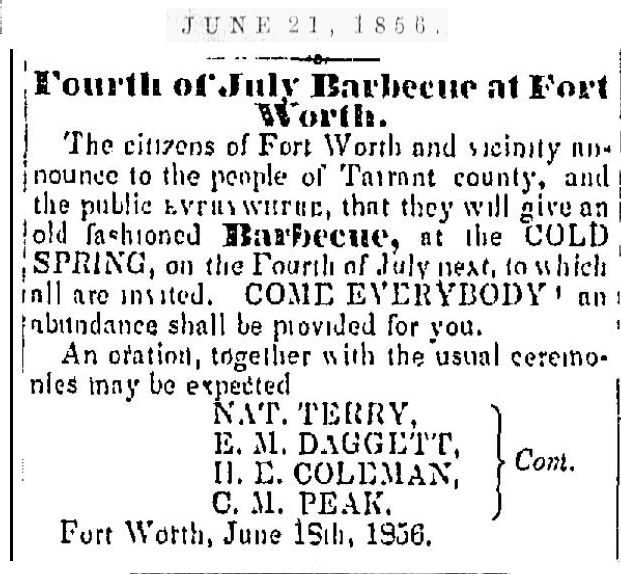

In fact, by 1856 residents were holding an annual Independence Day barbecue at the Cold Springs. On the arrangements committee were Carroll M. Peak and Ephraim Merrell Daggett. Oh, and Nat Terry. More on him later.

In fact, by 1856 residents were holding an annual Independence Day barbecue at the Cold Springs. On the arrangements committee were Carroll M. Peak and Ephraim Merrell Daggett. Oh, and Nat Terry. More on him later.

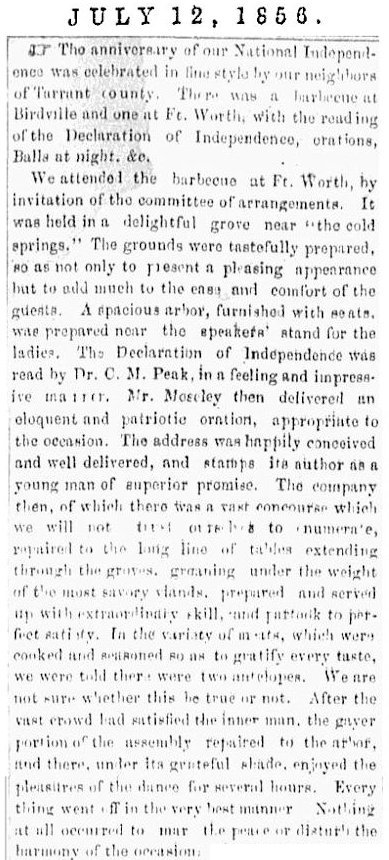

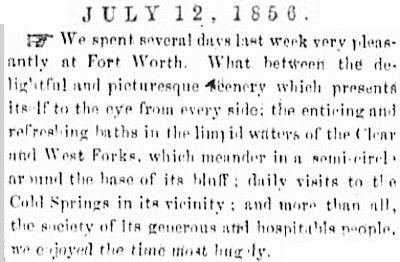

That summer of 1856 a representative of the Dallas Weekly Herald even came over to spend a few days in Fort Worth and to attend the Independence Day barbecue at the Cold Springs. The Dallas writer afterward waxed uncharacteristically ecstatic over Fort Worth’s amenities.

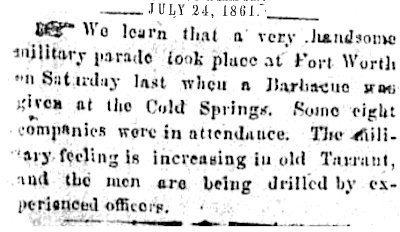

Five years later, as the Civil War raged, a barbecue at the Cold Springs on July 20 included a military parade. This was the barbecue at which attorney A. Y. Fowler and Sheriff John York got crossways with each other. A month later the two men would kill each other.

Five years later, as the Civil War raged, a barbecue at the Cold Springs on July 20 included a military parade. This was the barbecue at which attorney A. Y. Fowler and Sheriff John York got crossways with each other. A month later the two men would kill each other.

Even into the early twentieth century the Cold Springs was the scene of gatherings.

Even into the early twentieth century the Cold Springs was the scene of gatherings.

But notice that none of these clips gives readers a location of the Cold Springs. Back then local newspapers did not pinpoint local locations because they didn’t need to: Fort Worth was so small that readers knew where everything was located. Newspapers were writing for present readers, not future historians.

So what do we future historians know? Where exactly within the Samuels Avenue peninsula was the Cold Springs?

A clue is found in a 1949 Star-Telegram story about a letter written in 1893 by Simon B. Farrar, who had ridden with Colonel Johnson on that scouting trip in 1849: “Col. Johnson, Dr. Echols, Charles Turner, Joe Parker and myself came out from Shelby County, and after about a week at Johnson’s Station we started with Major Arnold and his command up the Trinity in search of a place to locate the regular United States troops. . . . We passed the first night near Terry Springs, now known as Cold Springs.”

A clue is found in a 1949 Star-Telegram story about a letter written in 1893 by Simon B. Farrar, who had ridden with Colonel Johnson on that scouting trip in 1849: “Col. Johnson, Dr. Echols, Charles Turner, Joe Parker and myself came out from Shelby County, and after about a week at Johnson’s Station we started with Major Arnold and his command up the Trinity in search of a place to locate the regular United States troops. . . . We passed the first night near Terry Springs, now known as Cold Springs.”

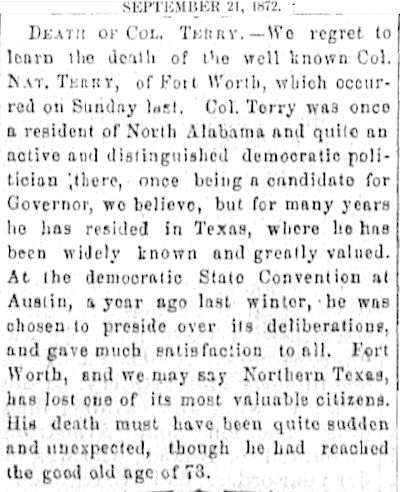

But why was the Cold Springs also known as “Terry Springs”? Because the spring was on the land of Colonel Nat Terry, who had been lieutenant governor of Alabama and had come to Fort Worth about 1854. In the northern part of the Samuels Avenue peninsula he established a plantation and built—well, actually his slaves did the building—a fine plantation house.

Wrote B. B. Paddock: “Colonel Terry settled the H. C. Holloway place northeast of and adjoining this city, in 1854. He bought this land from M. T. Johnson. . . . The Colonel’s house consisted of several rooms snow-white and well furnished, facing the south, fronted with a porch with floors of stone. There were separate apartments for the aged couple. He kept the most hospitable home I ever knew.”

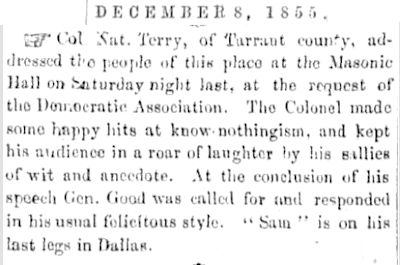

In 1855 Colonel Nat Terry spoke in Dallas as the guest of the Democratic Association. This short clip tells us something of the politics of the time. “Know-nothingism” refers to the “Know-Nothing Party,” which was a popular term for the American Party, which was an antiforeign, anti-Catholic secret society who wanted to keep control of the government in the hands of native-born citizens. The party was known as the “Know-Nothing Party” because members originally professed to know nothing of the party’s activities.

In 1855 Colonel Nat Terry spoke in Dallas as the guest of the Democratic Association. This short clip tells us something of the politics of the time. “Know-nothingism” refers to the “Know-Nothing Party,” which was a popular term for the American Party, which was an antiforeign, anti-Catholic secret society who wanted to keep control of the government in the hands of native-born citizens. The party was known as the “Know-Nothing Party” because members originally professed to know nothing of the party’s activities.

“Gen. Good” is probably John Jay Good, who became mayor of Dallas in 1880 and for whom the Good-Latimer Expressway is co-named. “Sam” is probably U.S. Senator Sam Houston. On July 24, 1855 Houston had issued a public letter endorsing the principles of the American Party.

Ironically, four years later Democrat Nat Terry would host “Sam” at Terry’s plantation as Houston (running as an independent) attended the Cold Springs barbecue on Independence Day and debated Democratic incumbent Hardin Runnels in the race for governor.

(Houston won.)

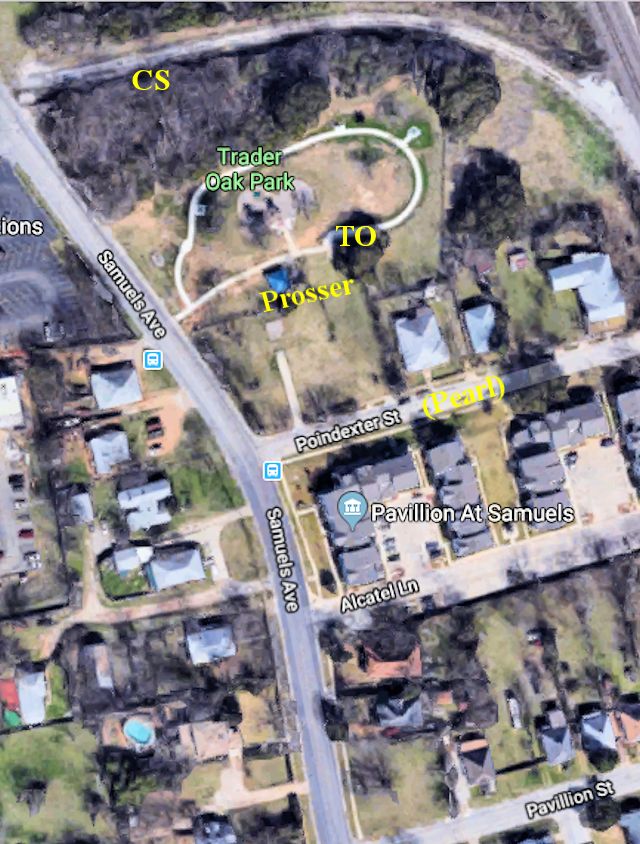

But where on Nat Terry’s plantation was the Cold Springs located? In The Fort That Became a City, historian Dr. Richard Selcer writes that the Cold Springs, “later called ‘Terry Spring,’” was at Live Oak Point, which was “just north of Pavilion Street and near the Treaty [Traders] Oak.”

Ah. Now we can put the Cold Springs into a modern context. Traders Oak Park is at 1206 Samuels Avenue. So, when you visit Traders Oak Park you are standing on the former plantation of Colonel Nat Terry; you are standing where Sam Houston once stood.

Ah. Now we can put the Cold Springs into a modern context. Traders Oak Park is at 1206 Samuels Avenue. So, when you visit Traders Oak Park you are standing on the former plantation of Colonel Nat Terry; you are standing where Sam Houston once stood.

Colonel Nat Terry died in 1872.

Colonel Nat Terry died in 1872.

But what became of his spring? In the ensuing years the Samuels Avenue peninsula has been subject to tremendous change: residential and industrial development, swaths of railroad tracks.

Historian and Samuels Avenue resident John Shiflet knows the Samuels Avenue area and its history. John said the late Lela Standifer of the Tarrant County Historical Commission showed him a Star-Telegram story from the 1920s that “pinpointed the location [of the spring] near Traders Oak and called it Terry Spring.”

John said he and Lela endured “the briars and brambles” of a grove of trees at Traders Oak Park to examine “a kidney-shaped depression.” Near that depression “we noticed a rivulet of water flowing . . . Lela had brought a small jar with her and filled it up to take to the Parks Department for testing. She later said tests indicated it was consistent with natural spring water.”

Indeed, if you are willing to poke around in the underbrush until your legs are lacerated and your socks are covered with stick-tights and “Indian needles,” you can find that boggy depression (middle photo) in that grove that lines the north border of the park. When I visited, the depression contained water, although I do not know if the water came from a spring or from surface runoff. The area had received no rain for a week when I was there. A few feet to the north, where a railroad track right-of-way cuts through the hillside, water seeps out of the hillside (bottom photo) from the direction of the depression.

Indeed, if you are willing to poke around in the underbrush until your legs are lacerated and your socks are covered with stick-tights and “Indian needles,” you can find that boggy depression (middle photo) in that grove that lines the north border of the park. When I visited, the depression contained water, although I do not know if the water came from a spring or from surface runoff. The area had received no rain for a week when I was there. A few feet to the north, where a railroad track right-of-way cuts through the hillside, water seeps out of the hillside (bottom photo) from the direction of the depression.

John says the depression over the years has silted up and also was once used as a neighborhood dump, but he is confident that the depression is Terry Springs/Cold Springs.

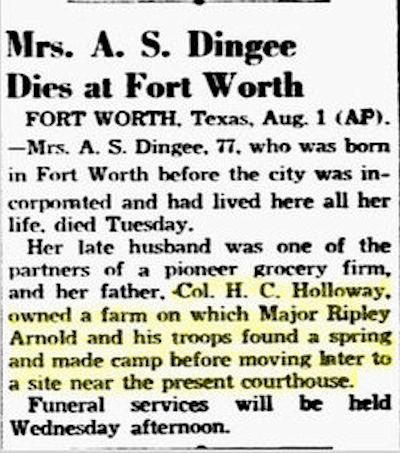

Here is some more evidence: the obituary of Pink Holloway Dingee in 1939. She was the widow of Fort Worth pioneer grocer Arthur S. Dingee. The Star-Telegram wrote that “her father, Col. H. C. Holloway, owned a farm on which Major Ripley Arnold and his troops found a spring and made camp before moving later to a site near the present courthouse.”

Here is some more evidence: the obituary of Pink Holloway Dingee in 1939. She was the widow of Fort Worth pioneer grocer Arthur S. Dingee. The Star-Telegram wrote that “her father, Col. H. C. Holloway, owned a farm on which Major Ripley Arnold and his troops found a spring and made camp before moving later to a site near the present courthouse.”

And where was the Holloway farm, which Paddock had said was later occupied by Colonel Terry?

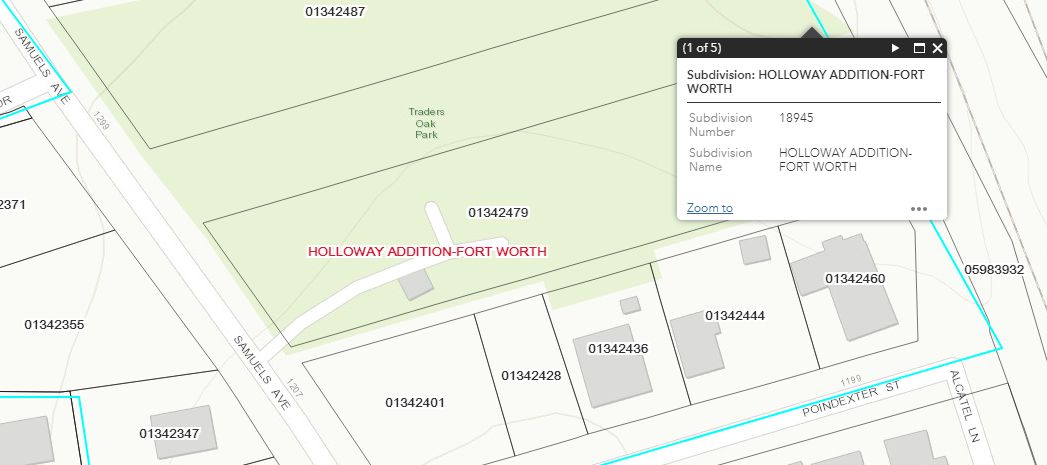

Much of the Samuels Avenue area, including Traders Oak Park and the depression that may be the remains of Terry Springs/Cold Springs, is in Holloway’s addition.

Much of the Samuels Avenue area, including Traders Oak Park and the depression that may be the remains of Terry Springs/Cold Springs, is in Holloway’s addition.

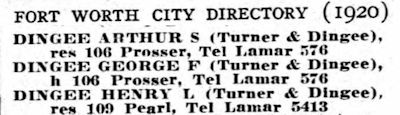

And where did the Dingees live?

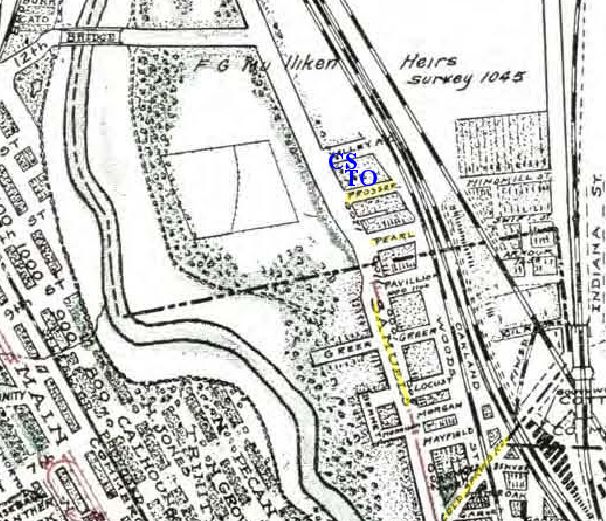

They lived on Prosser and Pearl streets in Holloway’s addition. And where were Prosser and Pearl streets?

This 1920 Rogers map shows that Prosser Street, now gone, was practically in the shade of Traders Oak and just 250 feet from the depression on the other side of the small park. It appears that the Holloway/Dingee families retained some of the farm after most of it was sold and developed. Quite possibly the Holloway/Dingee families owned the oak and the spring until the park was developed. Mrs. Dingee also owned the land at Samuels Avenue and Northeast 12th Street where Hangman’s Tree was located.

Pearl Street was renamed “Poindexter.”

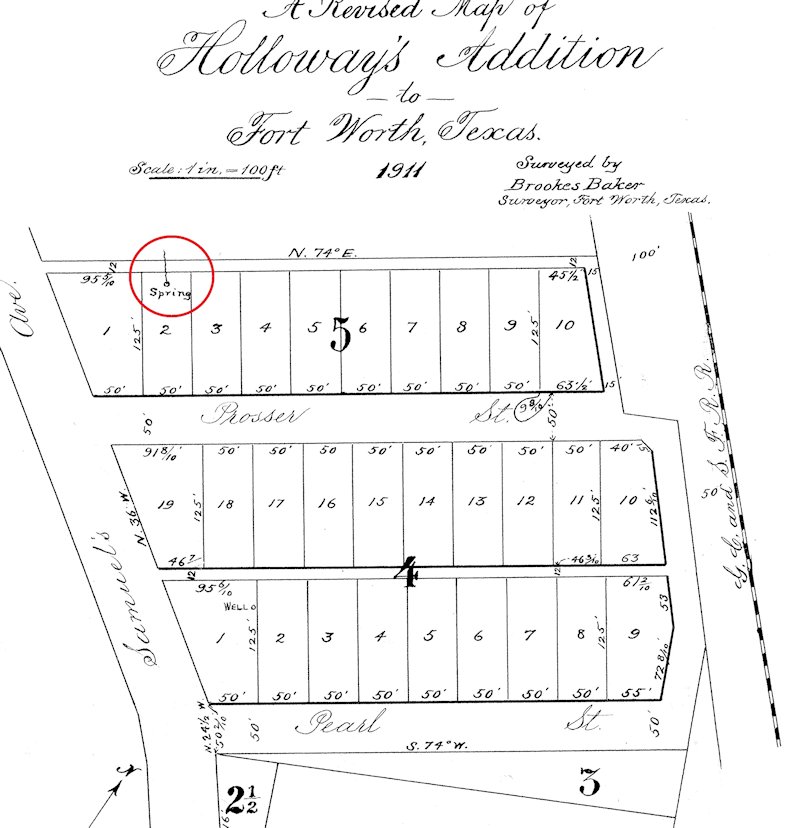

But wait! Andy Nold, a land surveyor and a resident of the Samuels Avenue peninsula, submitted this 1911 plat of Holloway’s addition. About two blocks north of the bend in Samuels Avenue at Pearl (Poindexter) Street is a spring in block 5, lot 2. That corresponds very nicely with the location of Shiflet’s Bog.

But wait! Andy Nold, a land surveyor and a resident of the Samuels Avenue peninsula, submitted this 1911 plat of Holloway’s addition. About two blocks north of the bend in Samuels Avenue at Pearl (Poindexter) Street is a spring in block 5, lot 2. That corresponds very nicely with the location of Shiflet’s Bog.

Wow. Great, huh? Mission accomplished! History wrapped up all neat and tidy. We are to be congratu—

But wait. Look at the lower right corner of the 1920 Rogers map. What’s that “Cold Springs Rd.” veering off of Samuels Avenue to the northeast? Hmmm. Not so neat and tidy after all.

But wait. Look at the lower right corner of the 1920 Rogers map. What’s that “Cold Springs Rd.” veering off of Samuels Avenue to the northeast? Hmmm. Not so neat and tidy after all.

Cold Springs Road must have been so-named because it led to or near a cold spring. But Cold Springs Road does not begin, end, or pass anywhere near the site of Terry Springs/Live Oak Point.

Ah, but at one time Cold Springs Road did pass near the Cold Springs as located by four twentieth-century publications:

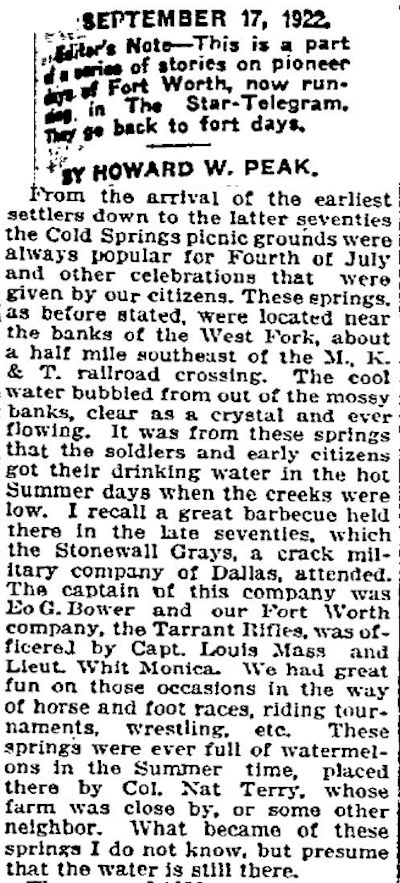

1. In 1922 the Star-Telegram printed a series of articles in which Howard Peak, born in 1856 in the abandoned fort, recalled life in early Fort Worth. Howard Peak surely had firsthand experience of the Cold Springs. In one article he recalled that the Cold Springs was located “near the banks of the West Fork, about a half mile southeast of the M. K. & T. railroad crossing.”

1. In 1922 the Star-Telegram printed a series of articles in which Howard Peak, born in 1856 in the abandoned fort, recalled life in early Fort Worth. Howard Peak surely had firsthand experience of the Cold Springs. In one article he recalled that the Cold Springs was located “near the banks of the West Fork, about a half mile southeast of the M. K. & T. railroad crossing.”

In another article Peak recalled that the Cold Springs was “located on the West Fork just east of his [Nat Terry’s] place . . . and was quite a resort in those days for the citizens as both cool water and splendid shade trees were to be had.”

In both articles Peak wrote in the past tense.

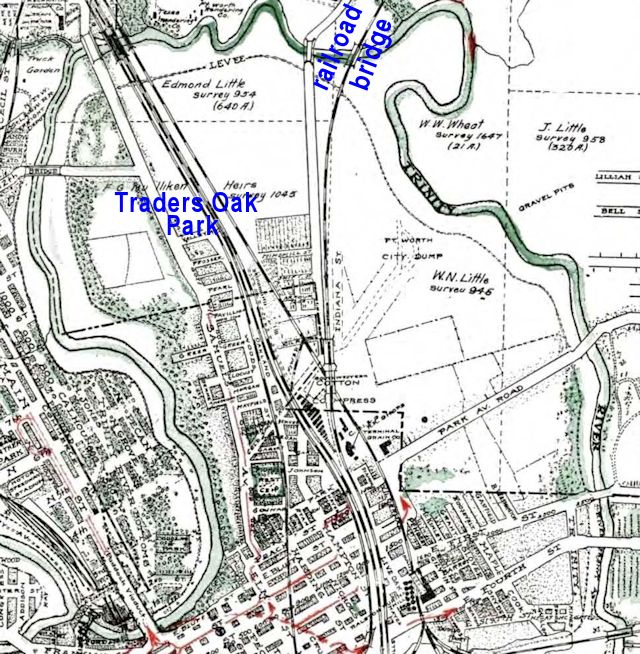

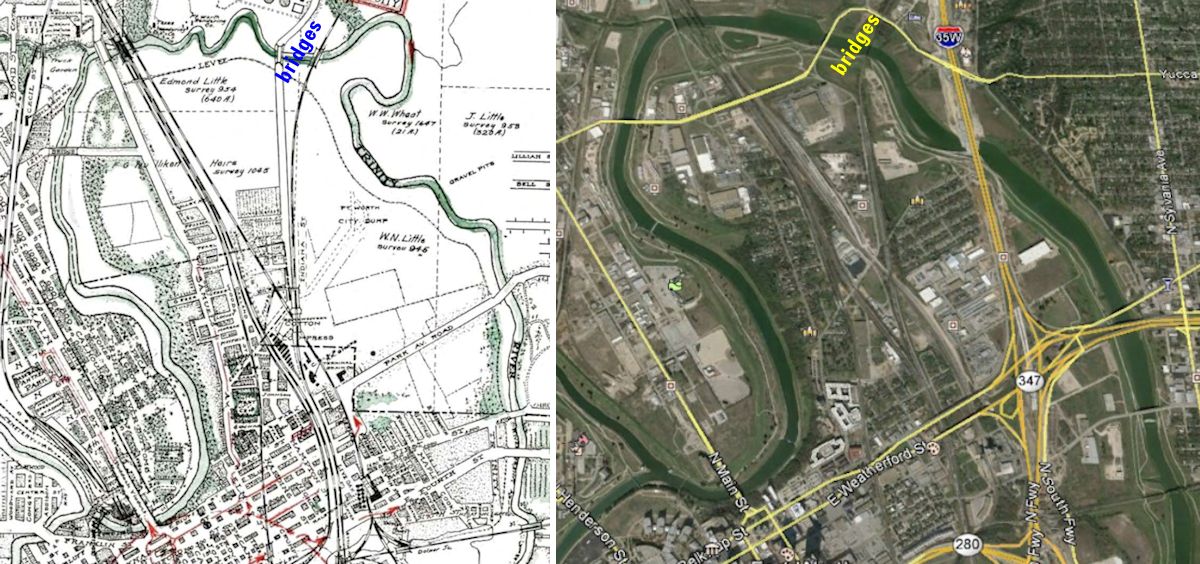

We don’t know if Peak in his memory was stepping off “a half mile southeast” along an “as the crow flies” line or along the channel of the river, which in his day was much longer in that stretch than it is today. That big bulge in the river east of the bridge was “orphaned” when the Army Corps of Engineers widened and straightened the channel after the flood of 1949 (see map below). (Map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

We don’t know if Peak in his memory was stepping off “a half mile southeast” along an “as the crow flies” line or along the channel of the river, which in his day was much longer in that stretch than it is today. That big bulge in the river east of the bridge was “orphaned” when the Army Corps of Engineers widened and straightened the channel after the flood of 1949 (see map below). (Map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

2. In 1949 Down Historic Trails of Fort Worth and Tarrant County (co-edited by historian Julia Kathryn Garrett) wrote: “Today, near-by the banks of the Trinity, a quarter-mile east from where the Cold Springs [Road] bridge spans the Trinity, one can find faintly bubbling springs.” The springs, which were located “in a grove of giant oaks and pecans,” gushed “clear, cold water.” The grove was gone by 1949; only scattered “monarch pecans” remained. But the location given is close to the location given by Peak.

The Cold Springs Road Bridge was removed in the 1950s after the river was channelized, and Cold Springs Road was rerouted into East Northside Drive. This photo from Down Historic Trails of Fort Worth and Tarrant County shows the railroad bridge (which Peak mentioned) east of where the Cold Springs Road Bridge was.

The Cold Springs Road Bridge was removed in the 1950s after the river was channelized, and Cold Springs Road was rerouted into East Northside Drive. This photo from Down Historic Trails of Fort Worth and Tarrant County shows the railroad bridge (which Peak mentioned) east of where the Cold Springs Road Bridge was.

To re-create today the angle of that 1949 photo of the railroad bridge, you have to stand on the other side of the river and much farther away.

To re-create today the angle of that 1949 photo of the railroad bridge, you have to stand on the other side of the river and much farther away.

The Cold Springs Road Bridge stood about four hundred feet west of the railroad bridge, so “a quarter-mile east” of the railroad bridge would put the Cold Springs about where the label is on this map.

The Cold Springs Road Bridge stood about four hundred feet west of the railroad bridge, so “a quarter-mile east” of the railroad bridge would put the Cold Springs about where the label is on this map.

3. In 1954 The Junior Historian of the Texas State Historical Association wrote that the Cold Springs was “situated about three-quarters of a mile northeast of Pioneers Rest Cemetery and about a rod [16.5 feet] from the western bank of the Trinity River.” Although “northeast” is not precise, “three-quarters of a mile” is. That location, too, would be near the location of the spring given by Peak.

4. And in 1972 Julia Kathryn Garrett wrote in Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph (which is based largely on oral histories): “Three-quarters of a mile away [from where Major Ripley Arnold and his soldiers had camped at Live Oak Point] cold water gushed from the south bank of the Trinity . . . under the thick shade of great oaks and giant pecan trees. They called it Cold Springs. . . . A road and a bridge leading to this location still bear the name Cold Springs.”

Likewise, Garrett’s location is similar to the locations given in 1922, 1949, and 1954.

But, Garrett also writes in her book that in 1859 Sam Houston spoke at the Independence Day barbecue “at Cold Springs near the foot of present-day Samuels Avenue.” Foot means “lowest part” or “termination” of something. Samuels Avenue originally ran north from Fort Worth up the peninsula and ended at the Terry plantation, which was later bought by Baldwin Samuel, hence the name of the street.

So, Garrett seems to describe both a spring on the river bank and a spring near Samuels Avenue.

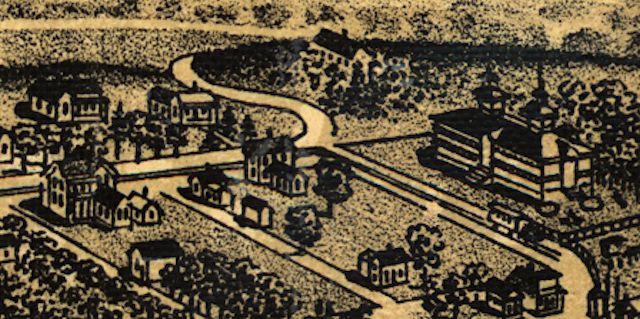

This detail from an 1886 Wellge bird’s-eye-view map of the Samuels Avenue area (then well outside the city limits) seems to show Samuels Avenue bending sharply to the left (west) near the new Rosedale Pavilion. Could the bend indicate where the public road Samuels Avenue ended and the private drive of the plantation began? Could the big house west of the pavilion have been the Terry/Samuel house? Traders Oak Park/Terry Springs is only three blocks north of where the pavilion was.

This detail from an 1886 Wellge bird’s-eye-view map of the Samuels Avenue area (then well outside the city limits) seems to show Samuels Avenue bending sharply to the left (west) near the new Rosedale Pavilion. Could the bend indicate where the public road Samuels Avenue ended and the private drive of the plantation began? Could the big house west of the pavilion have been the Terry/Samuel house? Traders Oak Park/Terry Springs is only three blocks north of where the pavilion was.

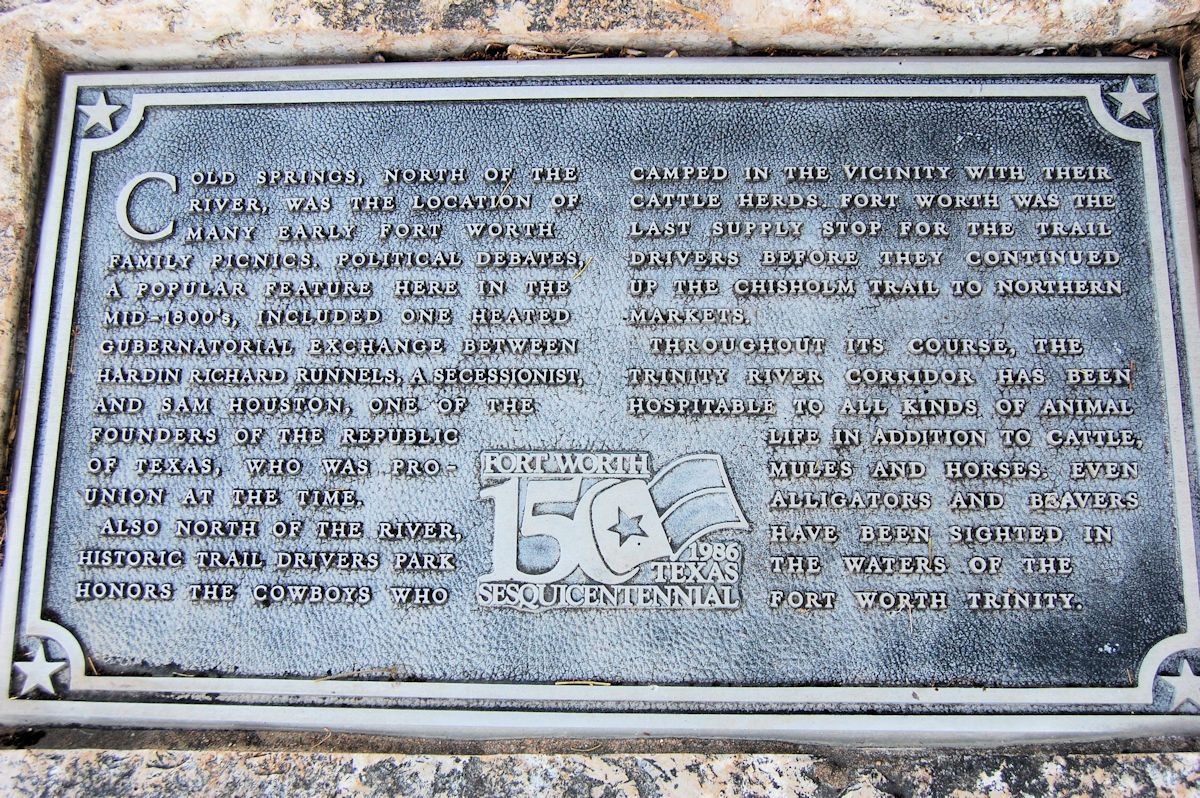

But wait! Just to muddy the (spring) waters further, this Texas sesquicentennial marker, located on the south bank of the river where Cold Springs Road once crossed the river at the bridge, says, “Cold Springs, north of the river, was the location of” etc., etc.

But wait! Just to muddy the (spring) waters further, this Texas sesquicentennial marker, located on the south bank of the river where Cold Springs Road once crossed the river at the bridge, says, “Cold Springs, north of the river, was the location of” etc., etc.

North of the river!

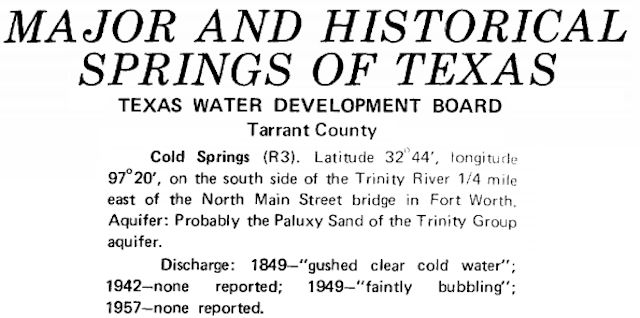

Here is an outlier. The Texas Water Development Board located the Cold Springs south of the river a quarter-mile east of the North Main Street bridge, which would put the springs near Samuels Avenue but farther south than others have put it.

Here is an outlier. The Texas Water Development Board located the Cold Springs south of the river a quarter-mile east of the North Main Street bridge, which would put the springs near Samuels Avenue but farther south than others have put it.

And B. B. Paddock in his Early Days in Fort Worth placed “the Cold Spring on the Trinity, on the Birdville road,” which is today’s East Belknap Street.

Regardless, remember that the river channel of 2021 is not the river channel of 1849 or even 1949. The map on the left is from 1919—before the flood control measures. Notice how much less convoluted the river is today, especially across the top of the Samuels Avenue peninsula where the “second” Cold Springs was. (1919 map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

Regardless, remember that the river channel of 2021 is not the river channel of 1849 or even 1949. The map on the left is from 1919—before the flood control measures. Notice how much less convoluted the river is today, especially across the top of the Samuels Avenue peninsula where the “second” Cold Springs was. (1919 map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

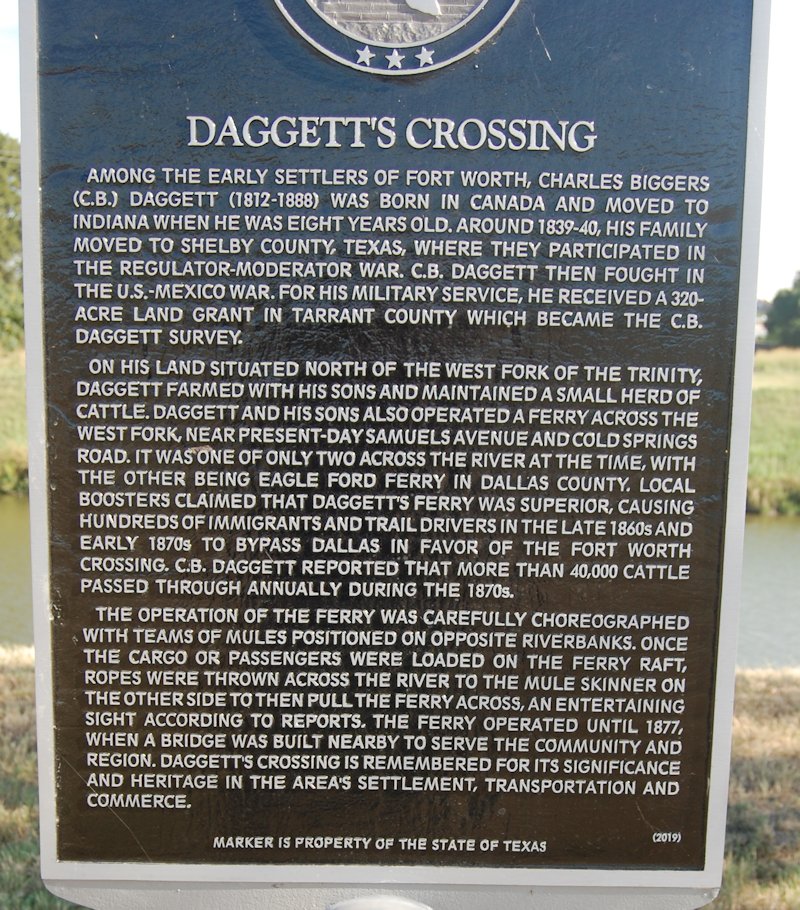

Spring or no spring, that short stretch of the river was a busy traffic corridor: In addition to the Cold Springs Road Bridge and the railroad bridge, northbound cattle drives on the Chisholm Trail forded the river at a shallows there.

And Charles Biggers Daggett (brother of Henry Clay and Ephraim Merrell), whose plantation was located where Mount Olivet Cemetery is today, operated a ferry there at Daggett’s Crossing until 1877, when the first county-funded bridge over the river was built near the crossing.

And Charles Biggers Daggett (brother of Henry Clay and Ephraim Merrell), whose plantation was located where Mount Olivet Cemetery is today, operated a ferry there at Daggett’s Crossing until 1877, when the first county-funded bridge over the river was built near the crossing.

So! It seems likely that there were two cold springs on the Samuels Avenue peninsula:

1. one at Live Oak Point/Traders Oak Park that may still occasionally flow

2. one that was on the river’s edge near today’s railroad bridge but that probably has been obliterated by changes to the river for flood control

Alas. We probably will never know the full story of the Cold Springs. At some point in time were both the Traders Oak Park spring and the river bank spring in use simultaneously? If so, why was the definite article the used (“the Cold Springs”)? Or did people differentiate with “Terry Springs” for one and “the Cold Springs” for the other?

Regardless of the questions, to settlers of early Fort Worth, it was good to have just one spring.

And even better to have a spare.

Thanks for this! I’m looking for these springs as part of a Texas-wide spring project. You might take a peek at Gunnar Brune’s “Springs of Texas” book where he refers to several cold springs in the area, including Daggett Cold Springs and wound up settling on one at 1301 Cold Springs Road due to its proximity to the fort as well as the thoughts of Gordan Kelley. Gunnar’s report for the TWDB has it all wrong, btw.

Thanks, Robert. Charles Daggett lived north/northeast of the river, and one historical marker says the cold springs were north of the river. Cold Springs Road also crossed the river at or near Daggett’s homestead.

There were two plats for Holloway’s Addition. I can’t locate my copy of the first plat right now, but it was vacated by “an order of the Commissioner’s Court of Tarrant County, Texas, recorded in Vol. 22, Page 123 of the minutes of said Court.” I think it might have been prepared by J.J. Goodfellow. The revised plat was prepared by Brookes Baker in 1911 and denotes a spring on Lot 2 of Block 5, which is the location of Mr. Shiflet’s boggy depression. The revised plat was prepared for Mrs. M.A. Holloway, a feme sole and owner of the land that was the original subdivision. I can send you a copy if you send your contact info to my email address.

Thanks, Andy, for the plat that confirms that a century ago there was a spring at Shiflet’s Bog in Traders Oak Park! There may well have been another cold spring closer to Cold Springs Road, but this is an important piece of the puzzle.

Hello Mike. I’ve enjoyed your website/blog and the thrill of the chase of trying to locate the original Cold Spring(s) is an interesting one. The Library of Congress has a high res civil engineer’s map from around 1880 that has Cold Springs Road coming off of Samuels to the NE and then continues straight in the line to the banks of the Trinity, ending up west of the railroad bridges. I’ll paste the link below.

Thanks, Ed. Isn’t that map great? A real snapshot of 1890. It’s included in the late Pete Charlton’s CD of old Fort Worth maps. Shows the driving park, the little pond in Marine Park, the first water works, the wire bridge west of the Main Street viaduct. Shows the planned city of East Fort Worth in Riverside, where C. W. Post and other investors planned a city with a trolley park (probably “Forest Park” on the map) and a college (probably “University Place” on the map). Below Oakwood Cemetery it also shows what appears to be a canal connecting the river west of Main with the river east of Main. Pete and I were never able to find anything on that.

1890 map

Just to the west of the railroad bridges, on the south bank they built in recent years the wakeboard park. The pond for the wakeboards seems to stay at a constant level, so I have wondered whether it is just fed by the Trinity River or whether there might be some spring flow sustaining it, given the proximity to the original spring site. The Fort Worth Water Department once depended on wells that were drilled in the area, which were largely responsible for dropping the water table so low that area springs and artesian wells failed. It would be most interesting to get access to Water Department records of current water table depth to determine whether any spring flow might still occur. Have you ever spoken with any of the Water Department folks?

Mike, I passed the wakeboard pond on my bike less than an hour ago. Because of its closeness to the river I have always assumed that the pond is fed by the river, but I have not talked to anyone. I agree that the springs must have been on the south bank but wanted to include all the theories I have come across. I also suspect there was more than one spring on the Samuels Avenue peninsula.

The location of Cold Springs is one of my favorite puzzles. I have visited the Trader’s Oak site many times and pondered the location of the original spring frequently while riding the Trinity Trails bike path along the stretch between the railroad bridge and Delga Park. It seems unlikely to me that the springs could have been located on the north river bank, because the residents of Fort Worth depended on it for fresh water in an era when the Trinity River had a wildly variable flow, from trickle to flood. Transporting water in the early days with no bridge would have been a huge problem. Any spring of appreciable size would have cut a path to the river, which does not seem to be the case with the spring near Trader’s Oak. It seems more likely then that the springs were on the south side, feeding into the Trinity per the photos from later days. If that is the case, the springs were buried first under a dump / landfill and then further devastated by the rechanneling of the river. I suspect the original spring location is buried under about 30-50 feet of dirt now. I have contemplated getting a boat and making a profile of water temperature measurements along the south bank, on the theory that if the spring still has any flow that some water might be getting forced out to the Trinity and that the colder water *might* be detectable. It is a crying shame that Tarrant County has treated its springs so harshly, with both Cold Spring and the spring at Bird’s Fort buried and lost to history. Most springs in the area failed as the water table dropped, just like the famous “limitless” artesian wells drilled here in the late 1800’s began to fail.

I was out at Calloway Lake not long ago for a post on the fort. Apparently the Viridian developer owns the land surrounding the lake, but heirs of a longtime owner of the lake still own the lake itself. But the cemetery and spring are long gone, and the whole area is fast becoming densely populated. I e-mailed both Viridian and the lake owner but got no reply.

Great story Mike! . . I had often wondered where exactly the Cold Spring was also.

Thanks, Keith. It’s one of the great (and frustrating) mysteries of this town.