The two men, each in his mid-thirties, died on the same day on the same battlefield. The last words of one (“Never let it be said that Texans lag in the fight”) were overheard. The death of the other came in a cloud of battle smoke so thick that no one saw him fall, much less heard any last words he may have said. Both men were generals. Both were trained as lawyers. And both would be buried three times before their mortal remains found their final home.

In this era of instant and endless news coverage, we forget how slowly news traveled in the days BT (before Twitter).

Case in point: On January 25, 1864 the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph printed a report on the role of Texas soldiers in the Civil War’s Battle of Missionary Ridge in Tennessee. The Battle of Missionary Ridge had been fought on November 25, 1863—two months before the newspaper account was published.

Of particular interest, the report mentions Confederate officers Colonel Hiram Bronson Granbury and General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne.

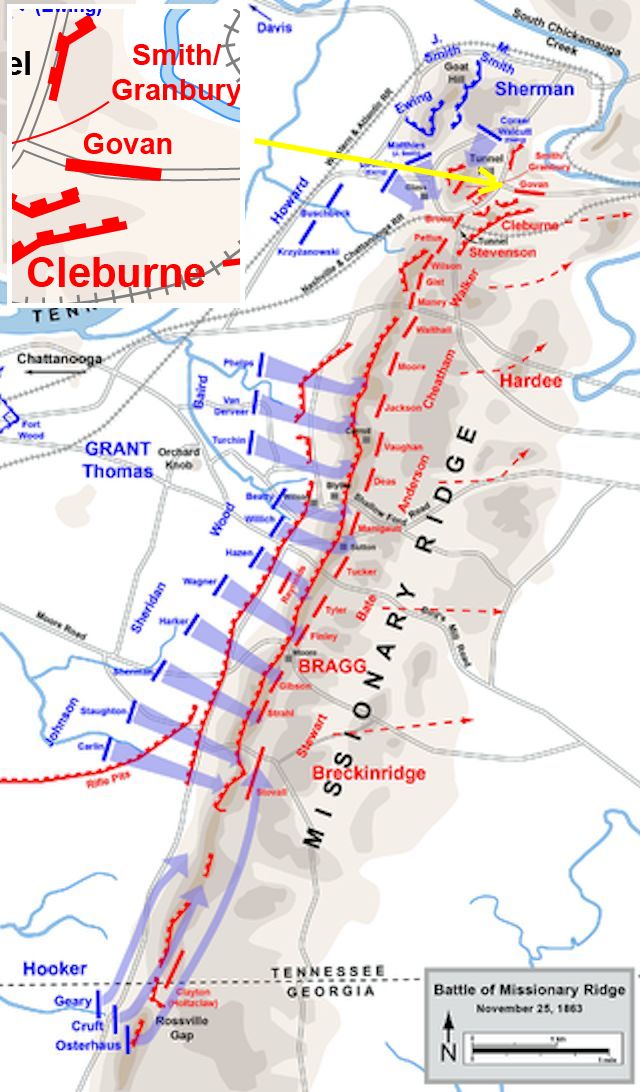

The detail inset in the upper left of this Wikipedia map locates the positions of Granbury and Cleburne during the Battle of Missionary Ridge.

The detail inset in the upper left of this Wikipedia map locates the positions of Granbury and Cleburne during the Battle of Missionary Ridge.

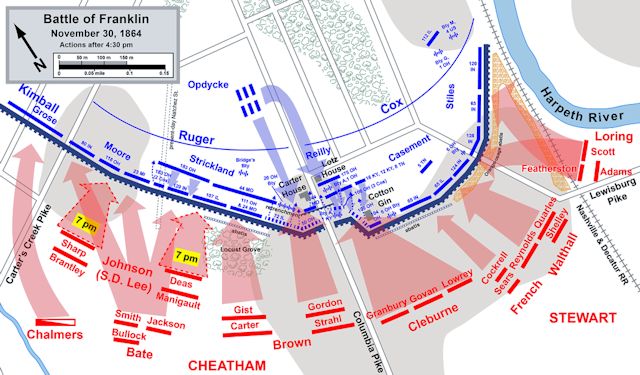

Patrick Ronayne Cleburne and Hiram Bronson Granbury survived the Battle of Missionary Ridge. But one year later and 130 miles away, on November 30, 1864 Cleburne and Granbury (by then a general) were killed at the Battle of Franklin in Tennessee. Four other Confederate generals died in the battle. This map from Wikipedia locates the positions of Granbury and Cleburne in the lower center.

Patrick Ronayne Cleburne and Hiram Bronson Granbury survived the Battle of Missionary Ridge. But one year later and 130 miles away, on November 30, 1864 Cleburne and Granbury (by then a general) were killed at the Battle of Franklin in Tennessee. Four other Confederate generals died in the battle. This map from Wikipedia locates the positions of Granbury and Cleburne in the lower center.

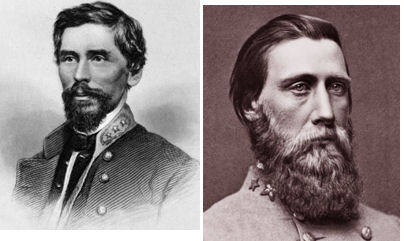

At left is General Cleburne, for whom the Johnson County city is named. Ronayne Cleburne was born in 1828 in County Cork, Ireland and lived in Ohio, Arkansas, and Mississippi. The Confederates were led into battle at Franklin by General John Bell Hood (right; see below).

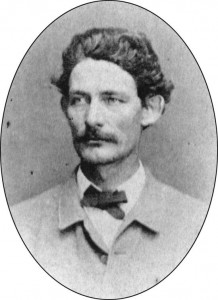

General Hiram Bronson Granbury was born in Mississippi in 1831.

General Hiram Bronson Granbury was born in Mississippi in 1831.

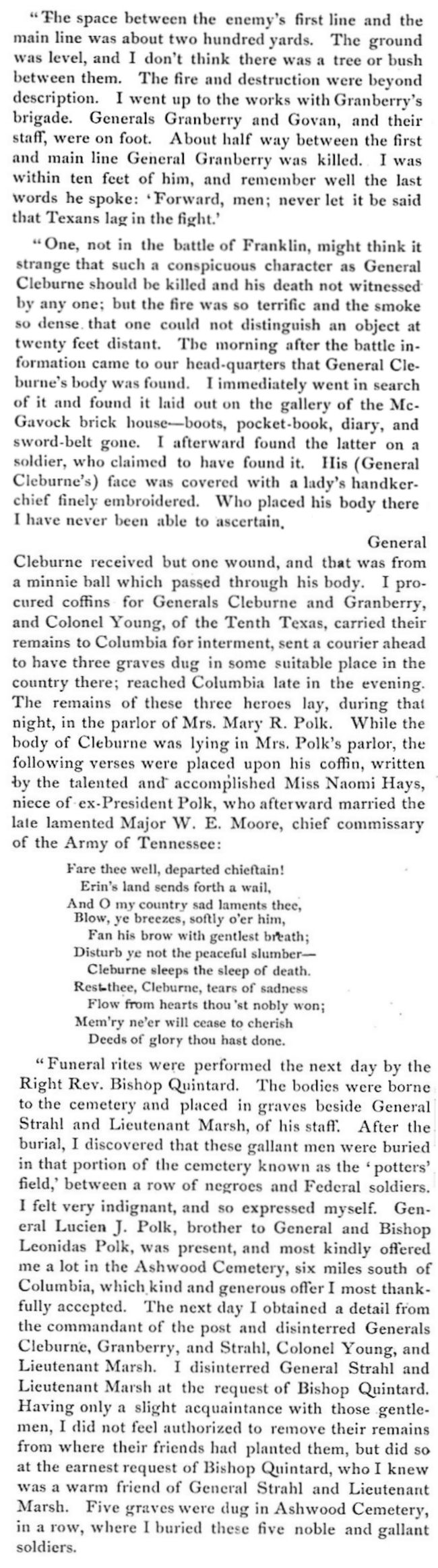

In Campaigns and Battles of the Sixteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteers, in the War Between the States, a war memoir published in 1885, Confederate veteran L. H. Mangum recalled the deaths of Granbury and Cleburne and Mangum’s role in the original burial (and prompt reburial) of the two generals near the Franklin battlefield. Mangum discovered that Cleburne and Granbury had been buried in “the ‘potters’ field’ between a row of negroes and Federal soldiers” and had the two men reburied.

Note the close proximity in which war and peace co-existed. The bodies of Cleburne and Granbury were taken from the battlefield to the parlor of a nearby home to be laid out. One of the residents of the home wrote a poem in honor of General Cleburne and placed it on his coffin.

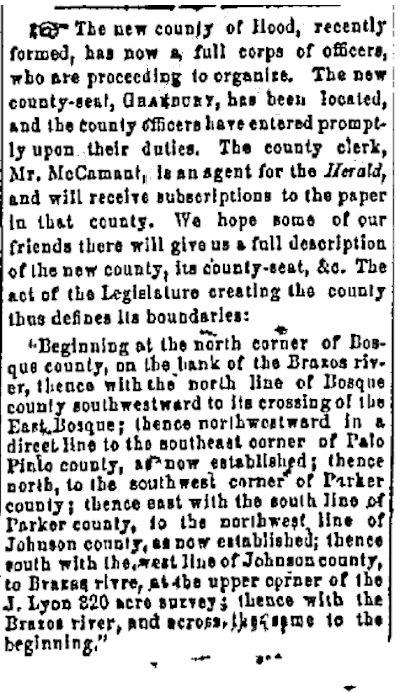

In 1866, two years after Granbury was killed, Hood County was formed by the state legislature and named for Confederate General John Bell Hood. The county seat was named for General Granbury. Clip is from the June 8, 1867 Dallas Weekly Herald.

In 1866, two years after Granbury was killed, Hood County was formed by the state legislature and named for Confederate General John Bell Hood. The county seat was named for General Granbury. Clip is from the June 8, 1867 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Town lots in the new town went on sale in 1868.

In 1870 General Cleburne was reburied—his third burial—in his adopted town of Helena, Arkansas.

In 1870 General Cleburne was reburied—his third burial—in his adopted town of Helena, Arkansas.

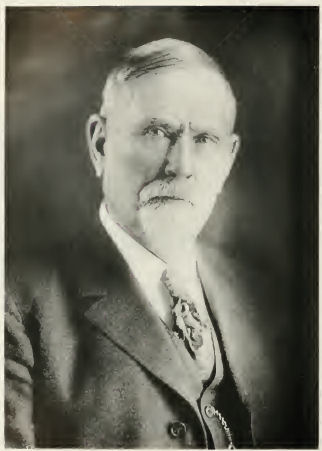

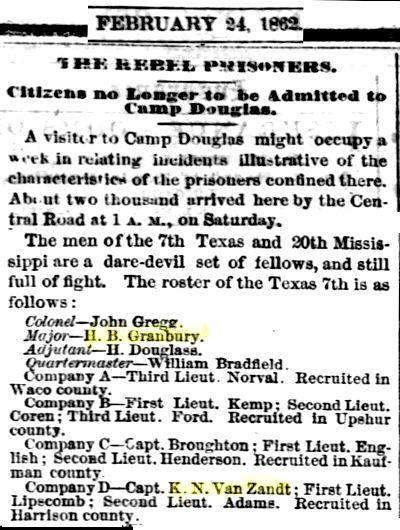

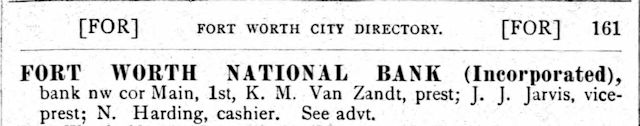

Fast-forward to 1893. Khleber Miller Van Zandt, Fort Worth civic leader and president of Fort Worth National Bank for forty-six years, had fought with Granbury at the Battle of Fort Donelson in 1862.

The two men had been taken prisoner and transported to the Union’s Fort Douglas at Chicago. Both men were later released in prisoner exchanges.

The two men had been taken prisoner and transported to the Union’s Fort Douglas at Chicago. Both men were later released in prisoner exchanges.

Van Zandt also fought with Granbury at the Battle of Missionary Ridge in 1863.

Van Zandt wrote in his autobiography that in 1893 the town of Granbury was given permission by General Granbury’s sister to move Granbury’s remains from Tennessee to the town named for him for reburial. The town sent its mayor, Dr. John Doyle, to Tennessee to fetch the remains. When Doyle got to Tennessee, he found that only bones and buttons had survived.

On the train trip back to the town of Granbury, Dr. Doyle stopped in Fort Worth and left the remains of General Granbury with Van Zandt for temporary safekeeping. General Granbury would be honored in a ceremony in Fort Worth and his remains then escorted to Granbury for the reburial ceremony in Granbury’s city cemetery a few days hence on November 30—the anniversary of Granbury’s death.

Van Zandt kept the remains of General Granbury in the safest place he knew of: the vault of Fort Worth National Bank.

Van Zandt kept the remains of General Granbury in the safest place he knew of: the vault of Fort Worth National Bank.

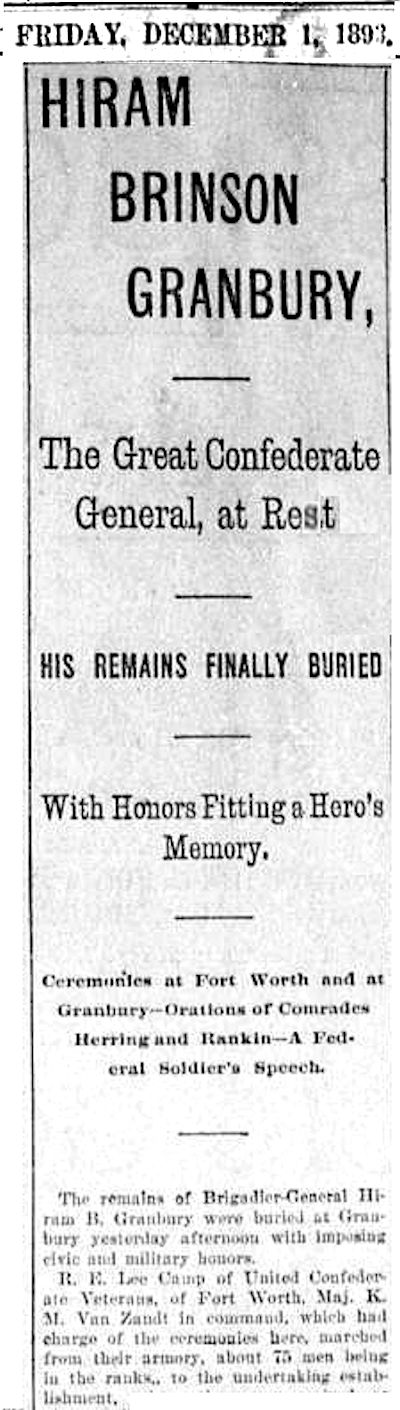

Major Van Zandt officiated at the ceremony honoring General Granbury in Fort Worth. Clip is from the Gazette.

Major Van Zandt officiated at the ceremony honoring General Granbury in Fort Worth. Clip is from the Gazette.

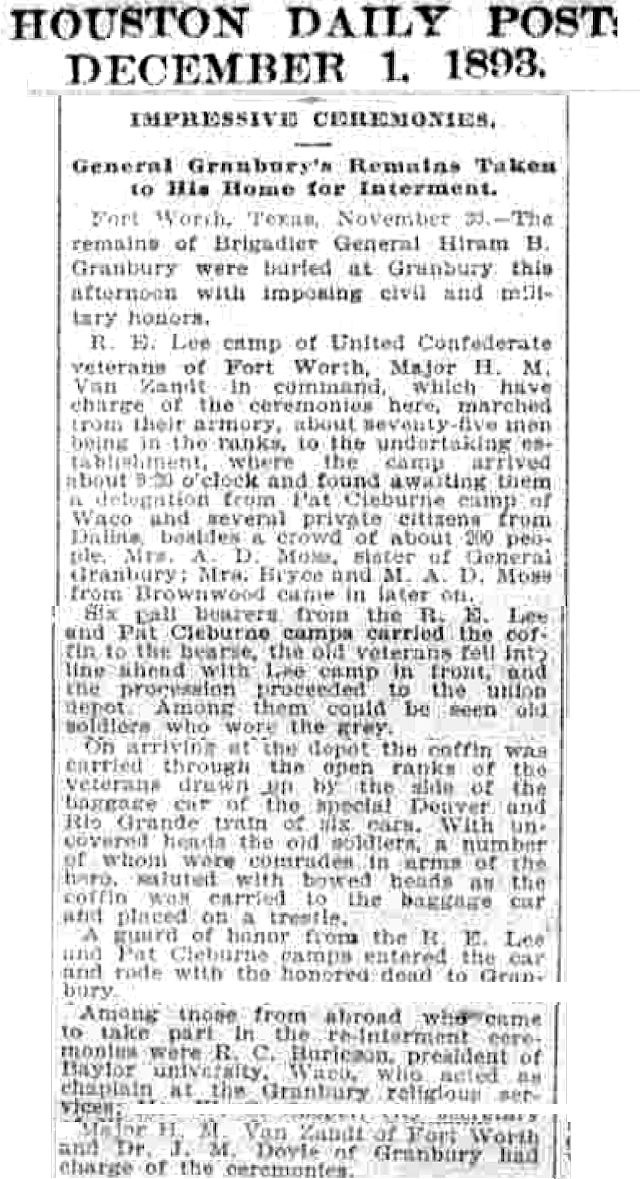

The remains of General Granbury were transported from Fort Worth on a special train of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad. Rufus Columbus Burleson, who was president of Baylor University (and who in 1854 had baptized Sam Houston), served as chaplain at the reburial ceremony of Granbury—Granbury’s third burial. Before the war General Granbury had been a resident of Waco and a McLennan county judge.

The remains of General Granbury were transported from Fort Worth on a special train of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad. Rufus Columbus Burleson, who was president of Baylor University (and who in 1854 had baptized Sam Houston), served as chaplain at the reburial ceremony of Granbury—Granbury’s third burial. Before the war General Granbury had been a resident of Waco and a McLennan county judge.

Other posts about Van Zandt:

Van Zandt: Father and Son, State and City (Part 1)

From Adams’s Beaver Hat to Dylan’s Coffee Table

Blue and Gray: “Best of Friends . . . As If We Had Fought Side by Side”

A Rock and a Lock: Old-Fashioned Customer Service at the Trinity River Bank

Hotel Block: From “Sad and Gloomy” to the Golden Goddess

Another great job, Mike. I as I was reading I thought, oh no, the bumpkins at Fort Worth probably lost the general’s remains. But no, they did good. Thanks for your hard work on this Thanksgiving weekend.

Thanks, Earl. A dead general who went AWOL before he could RIP certainly would have been scandalous.

Mike I have always enjoyed reading your writing and on several occasions taken joy at the opportunity to hear you speak. but I MUST bow down to your research abilities and work ethic. You are ‘da man! Thank you so much for all that you do.

Thanks, Dan. Your kind words about the blog made me chuckle because they arrived early today as I was uploading a third revision of the account of Granbury’s death and original burial. I woke up thinking of a detail I wanted to add. The commingling of war and peace during a civil war is so surreal. After the carnage on the battlefield, the bodies of those two generals were taken to the parlor of a nearby home to be laid out for burial. And from the death of a young Irishman came poetry.

when i went to work for Ft Worth National Bank, in 1971, the old bank vault was on a lower level hallway, on display. it was not that large. wonder what happened to it?

For one with a nickname of “Woodenhead,” it is amazing that there is a county AND a US Army facility named after him. Perhaps a fitting summary of Hood is from Wikipedia: “…he succumbed to the disease himself, …, leaving ten destitute orphans.”

There is a reason that Hood isn’t one of the four statues at the corners of the Dallas Confederate Memorial. Franklin was one of the most embarassing defeats of the Confederacy - ever.