Sometimes just one word hints at a story.

In Benbrook Cemetery, where Z. Boaz, James Benbrook, and other pioneers of the area are buried, one tombstone stands out because of one word chiseled on it:

“Assassinated.” (I know of only one other local tombstone that bears that word.)

“Assassinated.” (I know of only one other local tombstone that bears that word.)

More than 140 years of exposure to the elements have softened the letters of that one word, but the years have not softened the impact of the word or of the story behind it. It is a story of family, a story of false witness, a story of greed and the gallows.

The story begins with Samuel Houston Myers, who was born in South Carolina in 1810 and migrated westward to settle in Johnson County north of Alvarado in 1851 with wife Martha Wallace and their six children. Martha died in 1853, and in 1854 Sam married Cynthia Bales, who lived on a nearby farm. The Fort Worth Daily Democrat called Sam “the wealthiest farmer in Johnson County.” In 1854 he was one of the 107 residents who petitioned the state to create Johnson County. He was a generous man, a community-minded man. And he was a prolific man: Sam would have three wives and—before all was said and done and diapered—seventeen children. Sam’s first-born was forty-one years older than Sam’s last-born.

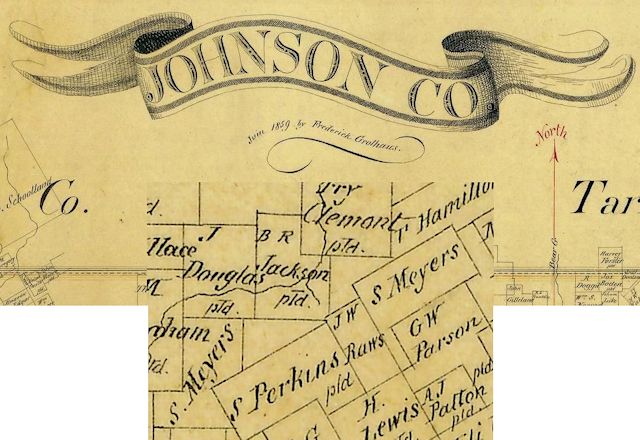

This detail of an 1857 map of Johnson County shows two parcels of Sam Myers land northeast of where Cleburne would be settled. The only town shown on the map is Buchanan, the county seat from 1856 until 1867.

This detail of an 1857 map of Johnson County shows two parcels of Sam Myers land northeast of where Cleburne would be settled. The only town shown on the map is Buchanan, the county seat from 1856 until 1867.

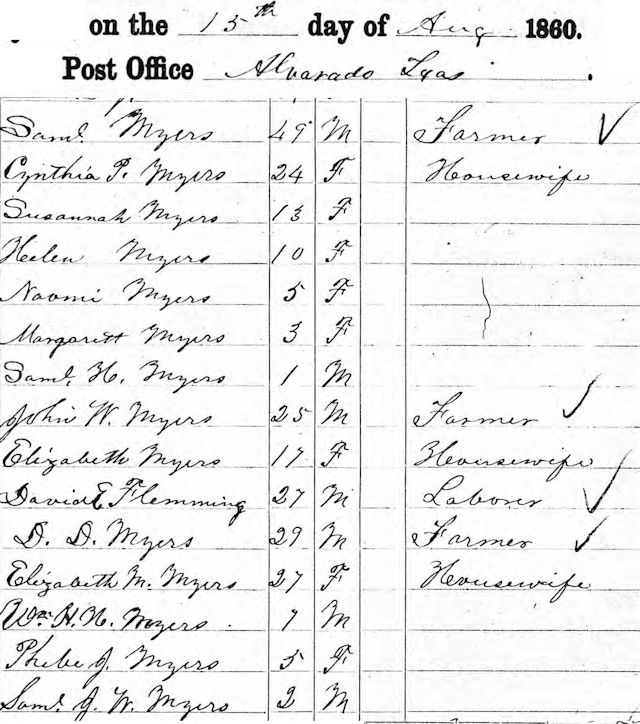

By 1860 the Myers clan of Johnson County filled most of a page of the census. Three members of note in this extended family are Sam’s second wife Cynthia, who was mother of seven of Sam’s children, twenty-five years younger than Sam, and younger than some of her stepchildren; one-year-old Samuel Houston Myers Jr.; and Thomas Jefferson Myers. After Sam Jr. was born, the father became known as “Old Sam” and the son as “Young Sam.”

By 1860 the Myers clan of Johnson County filled most of a page of the census. Three members of note in this extended family are Sam’s second wife Cynthia, who was mother of seven of Sam’s children, twenty-five years younger than Sam, and younger than some of her stepchildren; one-year-old Samuel Houston Myers Jr.; and Thomas Jefferson Myers. After Sam Jr. was born, the father became known as “Old Sam” and the son as “Young Sam.”

Cynthia died in 1865, and the last four of Old Sam’s seventeen children were born to Mary Agnes Hunter, who married Old Sam in 1866. Mary Agnes was thirty-three years the junior of Old Sam.

Old Sam died in 1874 at age sixty-three, plumb tuckered out by fatherhood, I reckon. Mary Agnes was just thirty-one. Old Sam had appointed Mary Agnes and her stepson Thomas Jefferson Myers as co-administrators of his estate.

And that’s when the trouble began.

For starters, Old Sam in his will had left Mary Agnes 183 acres of land with the stipulation that the land be returned to his estate upon her remarriage or death.

On January 4, 1877 Mary Agnes indeed did remarry. She married John A. Hester, a farmer who lived nearby. But after Mary remarried she failed to return the 183 acres to Old Sam’s estate. Some of Old Sam’s children, especially Thomas Jefferson (a child of Old Sam’s first wife) and Young Sam (a child of Old Sam’s second wife), felt that their new stepmother was cheating them. They also felt that Mary Agnes, as co-administrator of the estate, was stingy in doling out rightful money from the estate to the children. They also feared that the still-young Mary, in her new marriage, would bear more children, who might claim part of Old Sam’s estate.

But the marriage of Mary Agnes Hunter Myers and John A. Hester would be a short one.

After sunset on February 21, 1877 Mary Agnes, her new husband, and her son Lewis, age eleven, were eating supper at the dinner table in the Hester farmhouse. The room had a single window. Suddenly a shotgun blast fired through that window rattled the plates and deafened the diners. Twelve feet away from the window, Mary was hit in the head and was dead by the time she slumped to the floor.

The headline in the Fort Worth Daily Democrat on February 25:

Murdered

A Bride of Three Weeks Murdered in Cold Blood

She Is Riddled with a Load of Buckshot

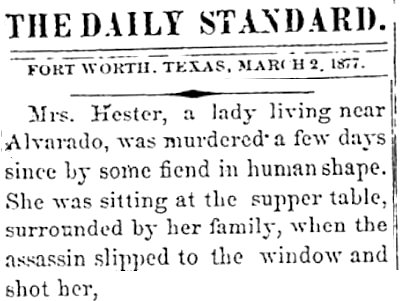

Neither John Hester nor Lewis Myers saw the assassin. The report of the Daily Fort Worth Standard on March 2 was short but graphic. I have deleted part.

Neither John Hester nor Lewis Myers saw the assassin. The report of the Daily Fort Worth Standard on March 2 was short but graphic. I have deleted part.

Mary Agnes Hester originally was buried in Hunter Cemetery east of Benbrook. But the bodies buried in that cemetery were relocated to Benbrook Cemetery in 1949 because of the impoundment of Benbrook Lake by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Mary Agnes Hester originally was buried in Hunter Cemetery east of Benbrook. But the bodies buried in that cemetery were relocated to Benbrook Cemetery in 1949 because of the impoundment of Benbrook Lake by the Army Corps of Engineers.

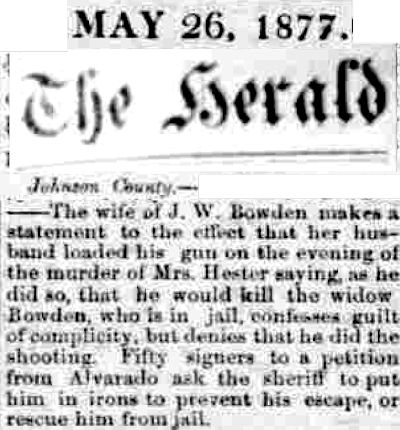

After the shooting in 1877, people examining the Hester property found footprints that led from the Hester house across a plowed field to where a horse had stood for some time. Hoofprints led from that spot to the home of James Bowden. Bowden was a son-in-law of Old Sam, having married daughter Mollie.

Bowden was arrested and jailed in Cleburne for the murder of Mary Agnes Myers, his wife’s stepmother.

Then, one night as Bowden was awaiting trial, some men wearing hoods took Bowden from his jail cell, placed him on a horse with a noose around his neck, and led him to a wooded area out of town. Upon interrogation by Sheriff John C. Brown, Bowden claimed that he, along with Thomas Jefferson Myers, had merely helped plan the murder of Mary Agnes Myers and that Young Sam had actually killed her.

Soon James Bowden’s misery had company: Thomas Jefferson Myers and Young Sam also were jailed and charged with murder.

During the trials of the three men there was plenty of suspicion to spread around.

The Case Against Young Sam

Witness Albert Combs testified that Young Sam said that he “had been to Mrs. Hester’s a few days before, and had cursed her out, and called her a d—d old bitch and that if he could not get revenge one way he would another.”

Witness Frank Williams testified that Young Sam, “in talking about his father’s wives, said that he was told the first of them was a good woman, and he knew his mother was a good woman, but that the last one, now Mrs. Hester, was a G-d-d—d bitch, and he intended to blow her brains out the first time she crossed him or his sisters.”

Mollie Bowden—wife of defendant James Bowden but sibling of defendants Young Sam and Thomas Jefferson Myers—originally testified that Bowden shot Mary Hester. But Bowden subsequently huddled with Mollie in his jail cell and persuaded her to change her testimony to claim that Young Sam, her brother, had shot Mary Hester.

Mollie Bowden—wife of defendant James Bowden but sibling of defendants Young Sam and Thomas Jefferson Myers—originally testified that Bowden shot Mary Hester. But Bowden subsequently huddled with Mollie in his jail cell and persuaded her to change her testimony to claim that Young Sam, her brother, had shot Mary Hester.

Defendant James Bowden testified that on the day of the murder of Mary Agnes Hester he had met Young Sam at a crossroads near the Hester property and had lent Young Sam a shotgun loaded with large shot. Bowden said he then had held Young Sam’s horse as Young Sam walked toward the Hester house with the shotgun. Bowden said that he soon heard a gunshot and that Young Sam returned, said he had killed his stepmother at the supper table, and asked Bowden to reload the shotgun with smaller shot.

The Case Against Thomas Jefferson Myers

Defendant James Bowden testified that he had heard Thomas Jefferson Myers complain that his father’s estate had given him “a heap of trouble.”

Witness John Clarriage, a son-in-law of Young Sam and Thomas Jefferson Myers, testified that the latter said “that the trouble had just begun, and that he did not know where in the devil it would stop.”

Witness A. J. Wynne testified that he heard Thomas Jefferson Myers say that if Mary Agnes Myers remarried after the death of Old Sam, “she would get her foot into it G-d-d—d bad.”

The Case Against Both Brothers

John Clarriage testified that on the day of the murder he had seen the two half-brothers, in a state of agitation, ride off toward the Hester house. Clarriage said that soon afterward he heard a gunshot and screaming from the Hester house.

The prosecution called even eleven-year-old Lewis Myers to testify. He said that on the day of his mother’s murder he had seen Young Sam and Thomas Jefferson Myers idling on horseback near the Hester farmhouse. Lewis said he heard them curse. He also testified that after the murder, Young Sam offered him $10 and a six-shooter if Lewis would leave home.

The Case Against James Bowden

Witness M. Rawlings testified that James Bowden had asked Rawlings to write a letter to Mary Hester warning her that unless she paid to Bowden’s wife Mollie some money owed to Mollie from Old Sam’s estate, Mary’s house would be set on fire and her brains would be blown out as she fled the burning house.

Another witness, Jack Turner, testified that Bowden offered him $50 to kill Mary Hester.

The Verdicts

Thomas Jefferson Myers was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang. Myers appealed, was granted a new trial, was found guilty again but this time sentenced to only life in prison. He appealed again. After three trials and three years in jail, he was found not guilty and set free.

Thomas Jefferson Myers was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang. Myers appealed, was granted a new trial, was found guilty again but this time sentenced to only life in prison. He appealed again. After three trials and three years in jail, he was found not guilty and set free.

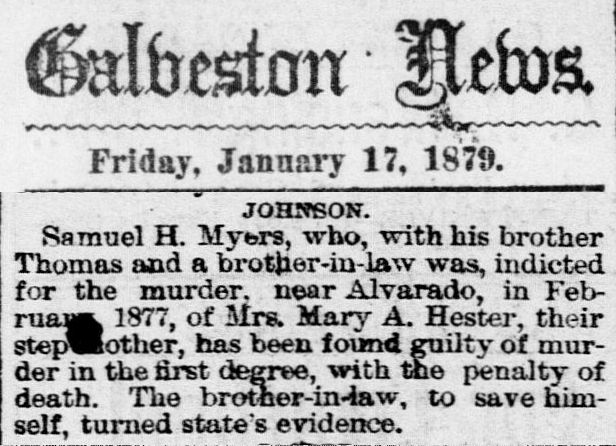

Young Sam’s trial was set for July 13, 1877 but was four times postponed until 1879. Based on the evidence of his brother-in law James Bowden, Young Sam was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

Young Sam’s trial was set for July 13, 1877 but was four times postponed until 1879. Based on the evidence of his brother-in law James Bowden, Young Sam was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

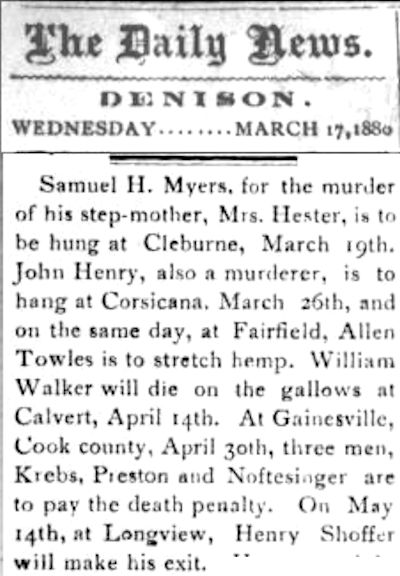

On March 17, 1880 the Denison Daily News printed a statewide capital punishment preview.

On March 17, 1880 the Denison Daily News printed a statewide capital punishment preview.

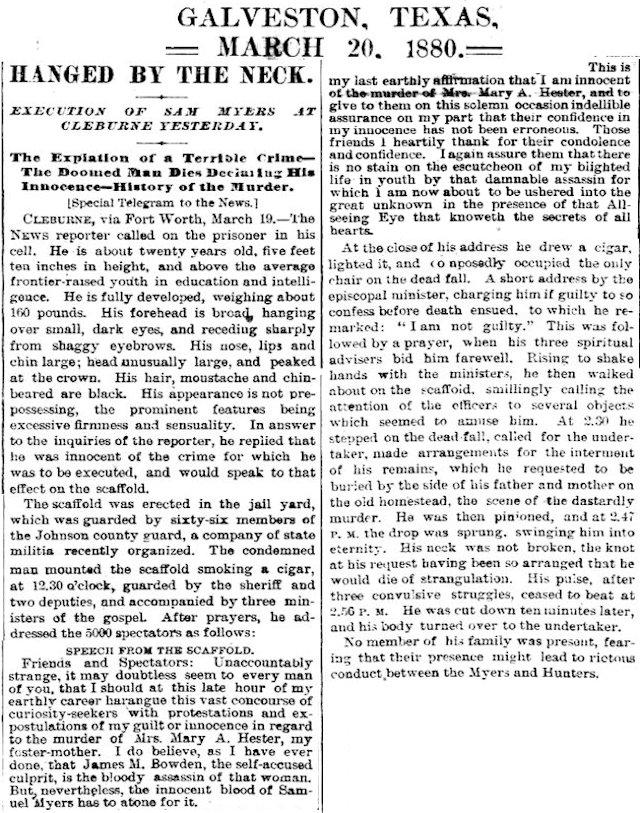

The Galveston Daily News devoted much of its March 20 front page to the hanging of Young Sam. This clip is a small excerpt.

The Galveston Daily News devoted much of its March 20 front page to the hanging of Young Sam. This clip is a small excerpt.

An estimated five thousand people gathered on the courthouse square to witness the only public hanging in Johnson County history.

Young Sam Myers addressed the crowd from the gallows: “The gun that shot and killed Mrs. Hester was heard at dark. At that time and after that time, up to 8 p.m., I was at the residence of Thomas Jefferson Myers, as was shown in the evidence before the jury. In the name of God, what sane man, without prejudice, could say that this unimpeached evidence created no doubt in his mind? Samuel Myers is an innocent victim of false testimony by hired emissaries.”

Young Sam would not live to be known as “Old Sam”: He was hanged at age twenty-one.

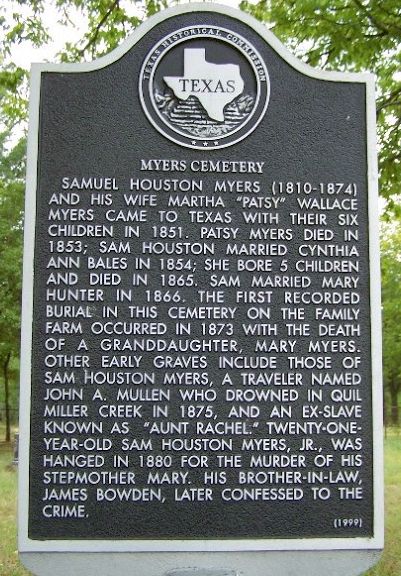

Young Sam was buried near his father, Old Sam, in Myers Cemetery north of Alvarado in Johnson County.

Young Sam was buried near his father, Old Sam, in Myers Cemetery north of Alvarado in Johnson County.

So. Our tally thus far: one brother dead, one brother free after three trials and three years in jail.

That leaves only Mary Agnes Hester’s son-in-law James Bowden, who had claimed that he had only lent his shotgun to assassin Young Sam. While Bowden was in jail in 1878 awaiting trial, his wife Mollie, whom he had persuaded to testify against her brother, deserted Bowden and moved to Louisiana.

Despondent, Bowden tried to commit suicide in his jail cell by chug-a-lugging a quart of whiskey that he had collected by saving small amounts that the jailer had given him over time.

Bowden’s first trial for murder ended with a hung jury. The jury in his second trial found him guilty of conspiring to commit murder. Bowden was sentenced to life in prison.

Fast-forward to 1895. James Bowden had served fifteen years in prison.

For him the good news: He had been paroled and was a free man.

For him the bad news: He was dying.

On his deathbed James Bowden made a confession: He—not the man who had gone to the gallows proclaiming his innocence—had assassinated Mary Agnes Hester as she ate her last supper.

(Thanks to Ken Smith for the tip.)

(Thanks to Ken Smith for the tip.)

As a decedent of the Myers family, this has been a very interesting read. Our family knew this story, but some of the details had been lost throughout the generations. I remember as a young girl, my grandparents going to see the cemetery and telling the story.

Thanks, Mike, I thoroughly enjoyed reading through this again.

Thanks to you, Ken, for leading me to a nineteenth-century version of the TV show “Dallas.”