Shakespeare had his Capulet-Montague feud. West Virginia and Kentucky had their Hatfield-McCoy feud.

And Texas had its Boyce-Sneed feud. By one estimate the feud led to seven homicides and two attempted homicides in one year.

Like the Capulet-Montague and Hatfield-McCoy feuds, the Boyce-Sneed feud fed on romance and revenge. But the Boyce-Sneed feud began not in the palazzos of Verona in the fourteenth century or in the hills and hollows of Appalachia in the nineteenth century but rather in the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel (see Part 2) in 1912.

The Metropolitan Hotel at 911 Main Street was built by Winfield Scott in 1898 as a haven for visiting cattlemen. “The only European hotel in the city,” the Met boasted. It was one of only five first-class hotels among the twenty-six in town at the time. The Met had a great location on Main Street. The streetcar line ran by the front door. Washer Brothers department store was across the street, and other retailers were nearby. The Texas & Pacific passenger station was only a few blocks away. A messenger from the station came to the hotel lobby hourly to announce arrivals and departures.

The Metropolitan Hotel at 911 Main Street was built by Winfield Scott in 1898 as a haven for visiting cattlemen. “The only European hotel in the city,” the Met boasted. It was one of only five first-class hotels among the twenty-six in town at the time. The Met had a great location on Main Street. The streetcar line ran by the front door. Washer Brothers department store was across the street, and other retailers were nearby. The Texas & Pacific passenger station was only a few blocks away. A messenger from the station came to the hotel lobby hourly to announce arrivals and departures.

All that swank and convenience made for good business. And things got only better: In 1899 T&P built its new passenger station even closer to the Met. And in 1902 the interurban line began running past the hotel on Main Street. In 1905 the hotel was expanded to a full city block bounded by Main and Commerce, 8th and 9th streets (just south of the 1921 Hotel Texas, which originally was called the “Winfield Hotel” after Scott).

Each of the enlarged Metropolitan’s 178 rooms had an outside view and steam heat. There was an artesian well in the courtyard, tuxedoed waiters in the dining room, a French chef in the kitchen, and Cowtown socialites in the ballroom. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The lobby of the Met was designed to create a first impression of refinement. It featured carved mahogany, cut glass, marble columns, marble stairway, hand-carved oak chairs, coffered ceiling, and spittoons aplenty. (Note the poster for King’s candies.)

The lobby of the Met was designed to create a first impression of refinement. It featured carved mahogany, cut glass, marble columns, marble stairway, hand-carved oak chairs, coffered ceiling, and spittoons aplenty. (Note the poster for King’s candies.)

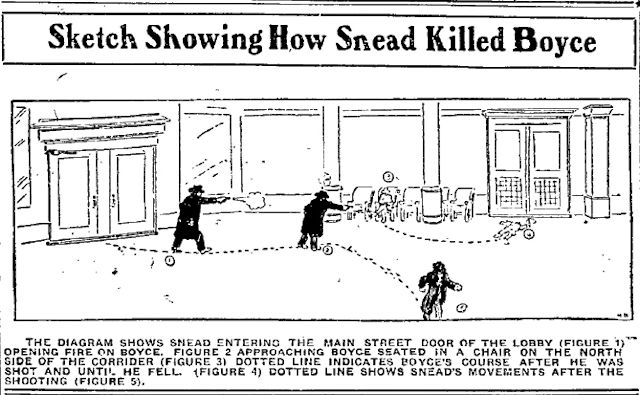

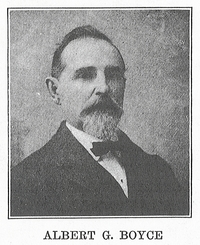

The gentility of that refined space was shattered on the night of January 13, 1912. Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr. sat reading a newspaper in one of those hand-carved oak chairs when John Beal Sneed burst into the crowded lobby and, without a word, fired four shots from a .22-caliber automatic pistol “with the rapid succession of a Gatling gun” at Boyce from eight feet away. Boyce staggered from his chair, fell to the floor, and died soon after at St. Joseph Infirmary. Boyce, seventy, was a prominent Amarillo banker and cattleman. For eighteen years he had been manager of the three million-acre XIT Ranch, the largest ranch under one fence in the world at the time.

The gentility of that refined space was shattered on the night of January 13, 1912. Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr. sat reading a newspaper in one of those hand-carved oak chairs when John Beal Sneed burst into the crowded lobby and, without a word, fired four shots from a .22-caliber automatic pistol “with the rapid succession of a Gatling gun” at Boyce from eight feet away. Boyce staggered from his chair, fell to the floor, and died soon after at St. Joseph Infirmary. Boyce, seventy, was a prominent Amarillo banker and cattleman. For eighteen years he had been manager of the three million-acre XIT Ranch, the largest ranch under one fence in the world at the time.

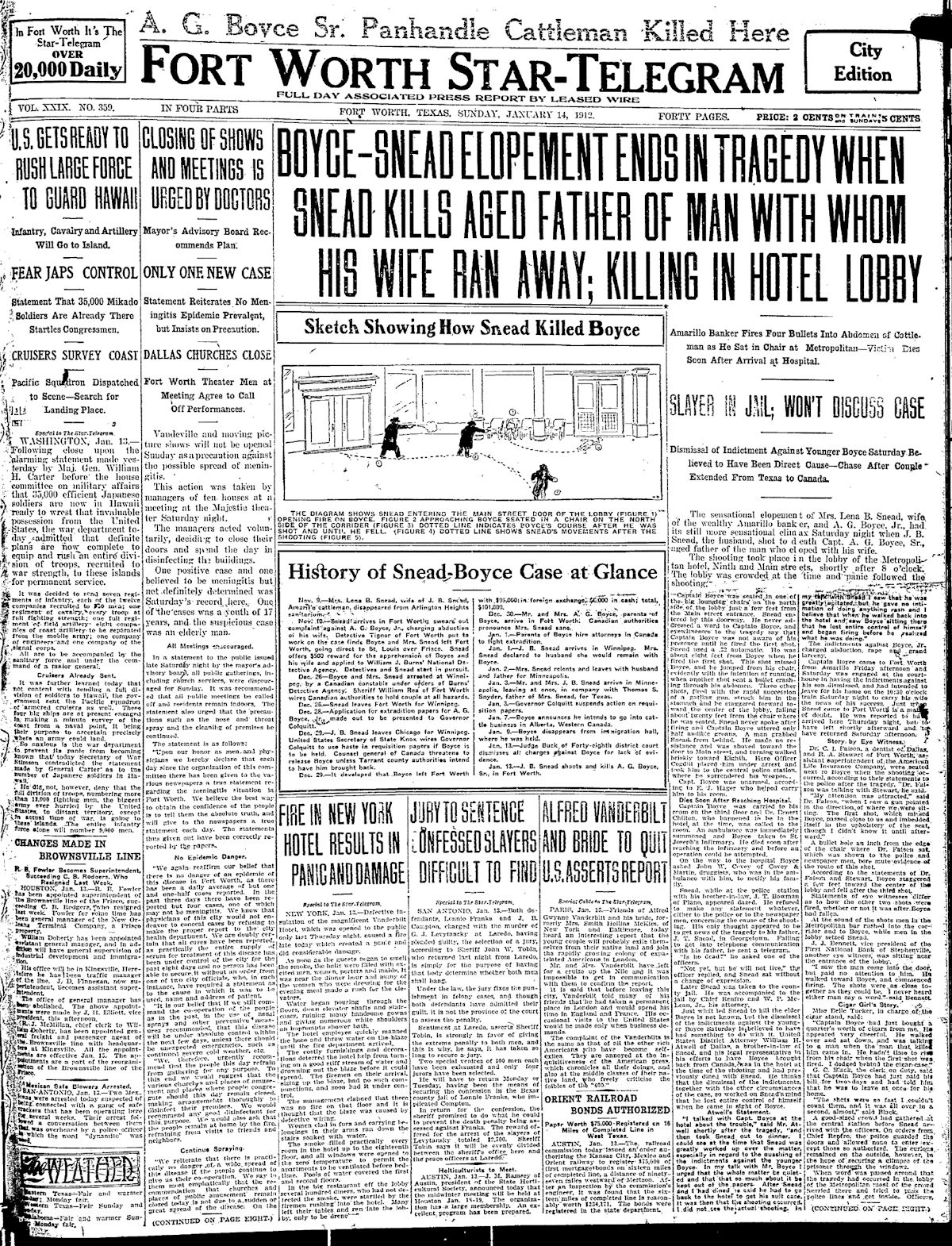

Today, of course, smartphone video clips of the Boyce-Sneed crime scene—if not of the crime itself—would be posted all over the Internet. But in 1912 people had to settle for a crude diagram in the Star-Telegram.

Today, of course, smartphone video clips of the Boyce-Sneed crime scene—if not of the crime itself—would be posted all over the Internet. But in 1912 people had to settle for a crude diagram in the Star-Telegram.

Sneed was arrested without resistance.

Uh-oh. Turns out that one man had run off with another man’s wife.

Uh-oh. Turns out that one man had run off with another man’s wife.

Let the feudin’ begin!

But first, before we sling any more hot lead, let’s go back . . . way back . . .

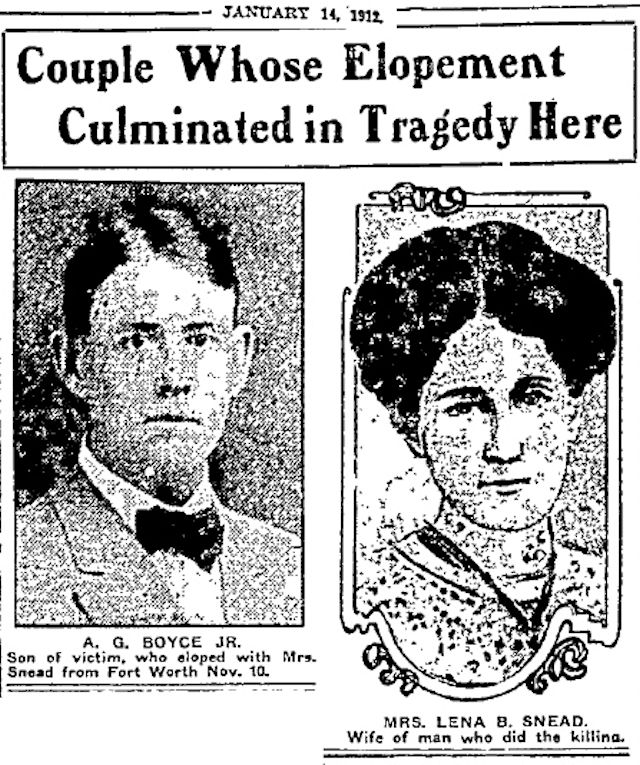

. . . back to the 1890s, when the three sides of our triangle were students at Southwestern University in Georgetown, and John Beal Sneed and Albert Gallatin Boyce Jr. (son of the dead man in the Metropolitan lobby) were rivals for Lena Snyder’s affection. Sneed won her heart and her hand, and he and Lena were married in 1900.

. . . back to the 1890s, when the three sides of our triangle were students at Southwestern University in Georgetown, and John Beal Sneed and Albert Gallatin Boyce Jr. (son of the dead man in the Metropolitan lobby) were rivals for Lena Snyder’s affection. Sneed won her heart and her hand, and he and Lena were married in 1900.

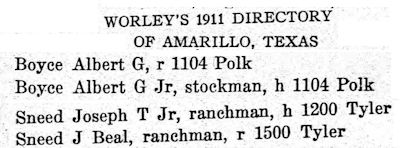

By 1911 the Boyce and Sneed families were living in Amarillo. In fact, they lived just a few blocks apart in an affluent neighborhood and saw each other socially. A brother of John Beal Sneed had been engaged to one of Boyce Jr.’s sisters, but she died before the wedding could take place. Boyce Jr., thirty-six, and Sneed, thirty-four, were cattlemen. Lena Snyder Sneed was thirty-three years old.

By 1911 the Boyce and Sneed families were living in Amarillo. In fact, they lived just a few blocks apart in an affluent neighborhood and saw each other socially. A brother of John Beal Sneed had been engaged to one of Boyce Jr.’s sisters, but she died before the wedding could take place. Boyce Jr., thirty-six, and Sneed, thirty-four, were cattlemen. Lena Snyder Sneed was thirty-three years old.

Then, on October 13, 1911, after Sneed and Lena had been married almost twelve years, Lena told Sneed that she no longer loved him, was infatuated with Boyce Jr., and planned to run away with him to South America, taking the Sneeds’ two children with her.

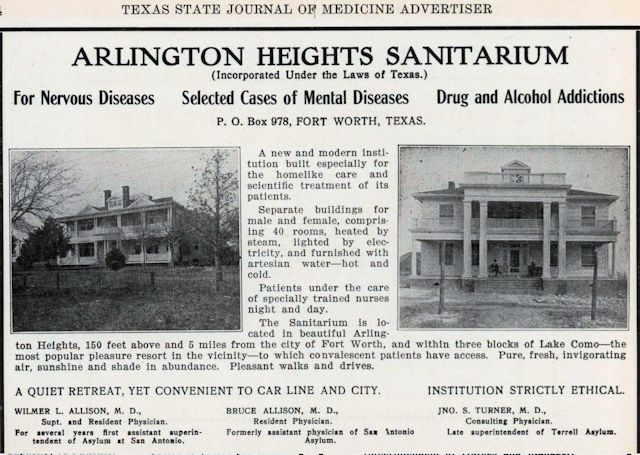

Sneed, declaring his wife to be temporarily insane, on October 17 (their anniversary) had her committed to Arlington Heights Sanitarium (photo from Texas Medical Association), located four blocks northeast of Lake Como. (Lena’s family insisted that she was sane and that Sneed had her cloistered to keep Lena and Boyce apart.)

Sneed, declaring his wife to be temporarily insane, on October 17 (their anniversary) had her committed to Arlington Heights Sanitarium (photo from Texas Medical Association), located four blocks northeast of Lake Como. (Lena’s family insisted that she was sane and that Sneed had her cloistered to keep Lena and Boyce apart.)

Lena was miserable in the sanitarium. She wrote to Boyce: “For God’s sake, get me away from here.”

Get her away from there he did.

Boyce withdrew $101,000 ($2.5 million today) from his bank in Amarillo and came to Fort Worth.

Lena was under guard at the sanitarium but was allowed to leave the premises in the custody of her nurse. So, on November 10 Lena arranged to meet Boyce at the train station, and they left for St. Louis.

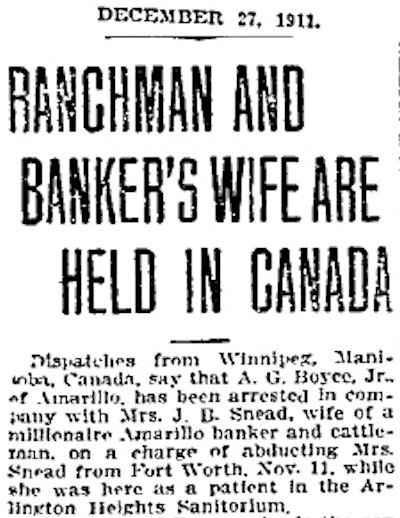

The next day Sneed arrived in Fort Worth to search for his wife. He swore out complaints accusing Boyce of abduction and kidnapping, hired a detective, and offered a reward for the apprehension of the two fugitives. Sneed and the detective followed Boyce and Lena to St. Louis, but the pair had already fled to Canada.

On December 26 Lena and Boyce were arrested in Winnipeg.

On December 26 Lena and Boyce were arrested in Winnipeg.

Four days later Mr. and Mrs. Boyce Sr. arrived in Fort Worth and checked into the Metropolitan Hotel. Boyce Sr. began working to get the charges against his son dropped and to fight extradition of his son from Canada. Meanwhile in Winnipeg, Lena was pronounced sane by authorities.

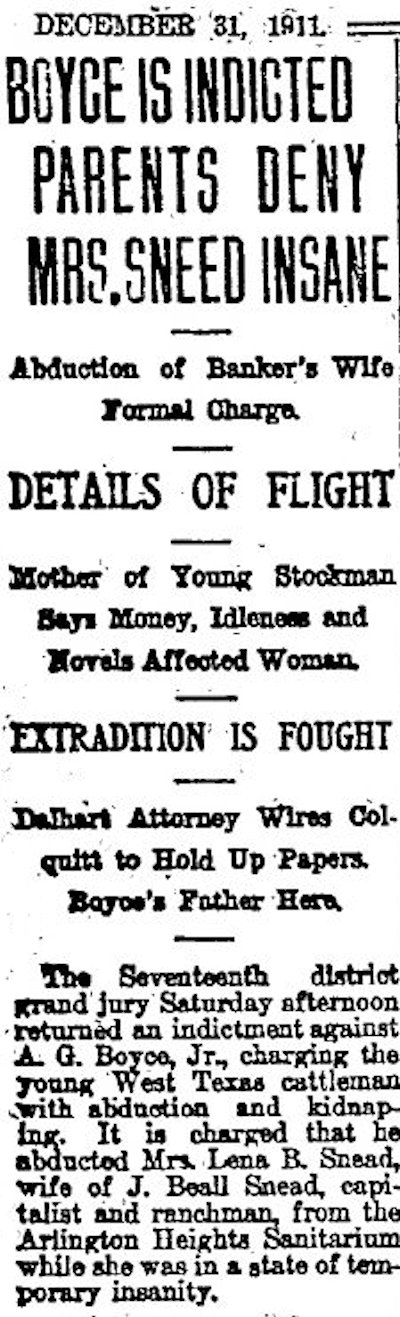

On December 30 Boyce Jr. was indicted for abduction and kidnapping. Said Mrs. Boyce Sr.: “Lena Sneed was sane when she ran off with my son, and she will swear to that when the trial comes off. . . . Albert [Boyce Jr.] was hypnotized by that woman. She hypnotized her husband, too, or he wouldn’t have offered a big reward for her. She has ruined her husband and my son and has broken my heart.”

On December 30 Boyce Jr. was indicted for abduction and kidnapping. Said Mrs. Boyce Sr.: “Lena Sneed was sane when she ran off with my son, and she will swear to that when the trial comes off. . . . Albert [Boyce Jr.] was hypnotized by that woman. She hypnotized her husband, too, or he wouldn’t have offered a big reward for her. She has ruined her husband and my son and has broken my heart.”

On January 1, 1912 Sneed arrived in Winnipeg to reclaim his wife, but Lena told him that she would remain with Boyce.

But the next day Lena relented and left with her husband for the States.

On January 7 Boyce Jr. announced that he was going to remain in Canada and go into the cattle business in Alberta. Two days later Boyce, facing extradition, disappeared from the immigration hall where he was being held.

On January 13 Sneed returned his wife to the Arlington Heights Sanitarium. Meanwhile, the state dropped charges of abduction and kidnapping against Boyce Jr.

And that’s when John Beal Sneed burst into the lobby of the Metropolitan Hotel and shot Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr.

And that’s when John Beal Sneed burst into the lobby of the Metropolitan Hotel and shot Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr.

Sneed shot Boyce Sr. because Sneed blamed him for working to get the charges against Boyce Jr. dropped and for helping Boyce Jr. break up Sneed’s marriage by helping Lena to escape from the sanitarium. (Photo from University of Texas Libraries.)

Sneed shot Boyce Sr. because Sneed blamed him for working to get the charges against Boyce Jr. dropped and for helping Boyce Jr. break up Sneed’s marriage by helping Lena to escape from the sanitarium. (Photo from University of Texas Libraries.)

On January 19 Lena was declared sane, and a judge ordered her discharge from the sanitarium. One dissenting doctor—the sanitarium’s Dr. Wilmer Allison—said Lena was “morally insane” because she had deserted her husband. Sneed’s attorney during the sanity hearing was William Pinckney (“Wild Bill”) McLean Jr., brother of Jefferson Davis McLean.

On January 19 Lena was declared sane, and a judge ordered her discharge from the sanitarium. One dissenting doctor—the sanitarium’s Dr. Wilmer Allison—said Lena was “morally insane” because she had deserted her husband. Sneed’s attorney during the sanity hearing was William Pinckney (“Wild Bill”) McLean Jr., brother of Jefferson Davis McLean.

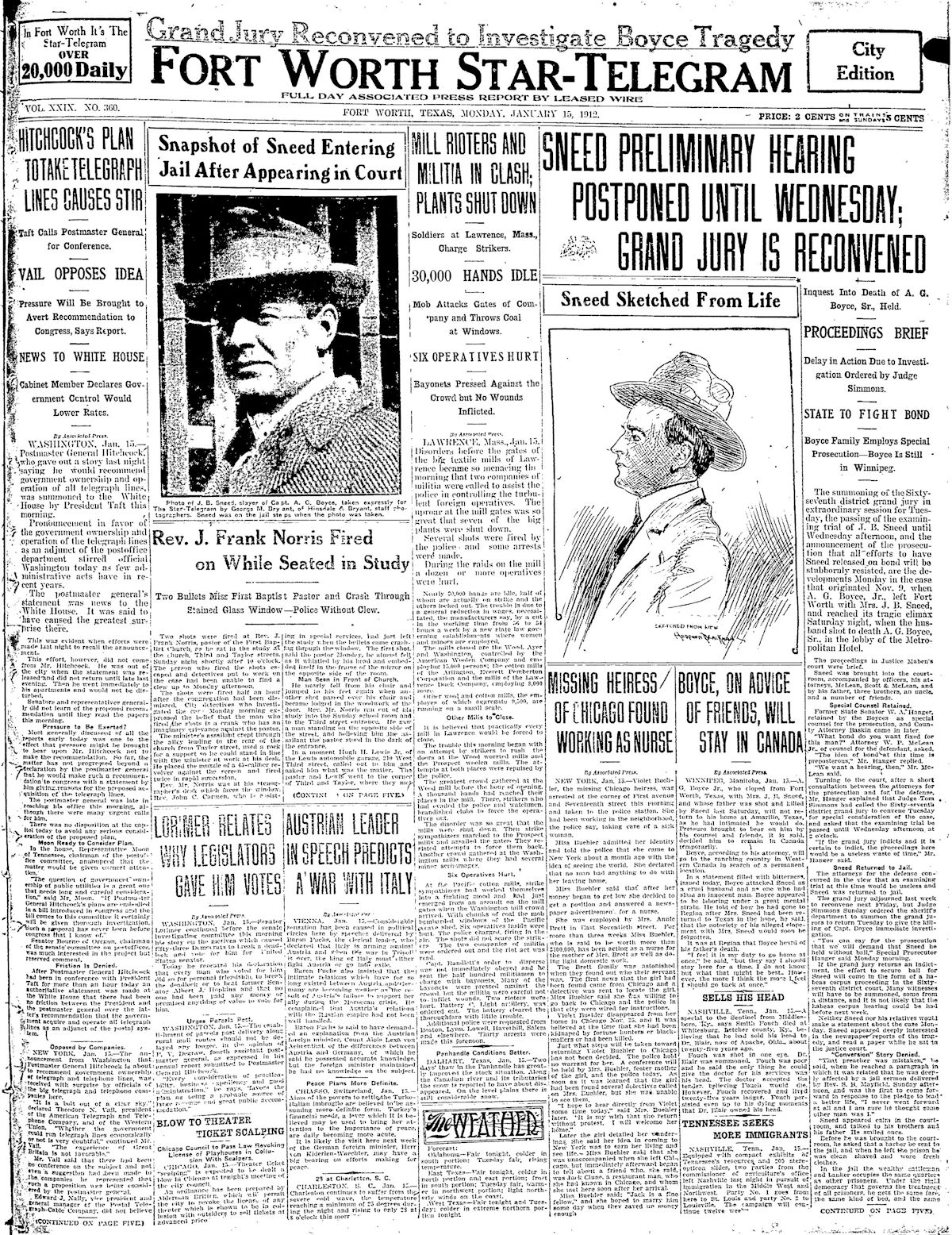

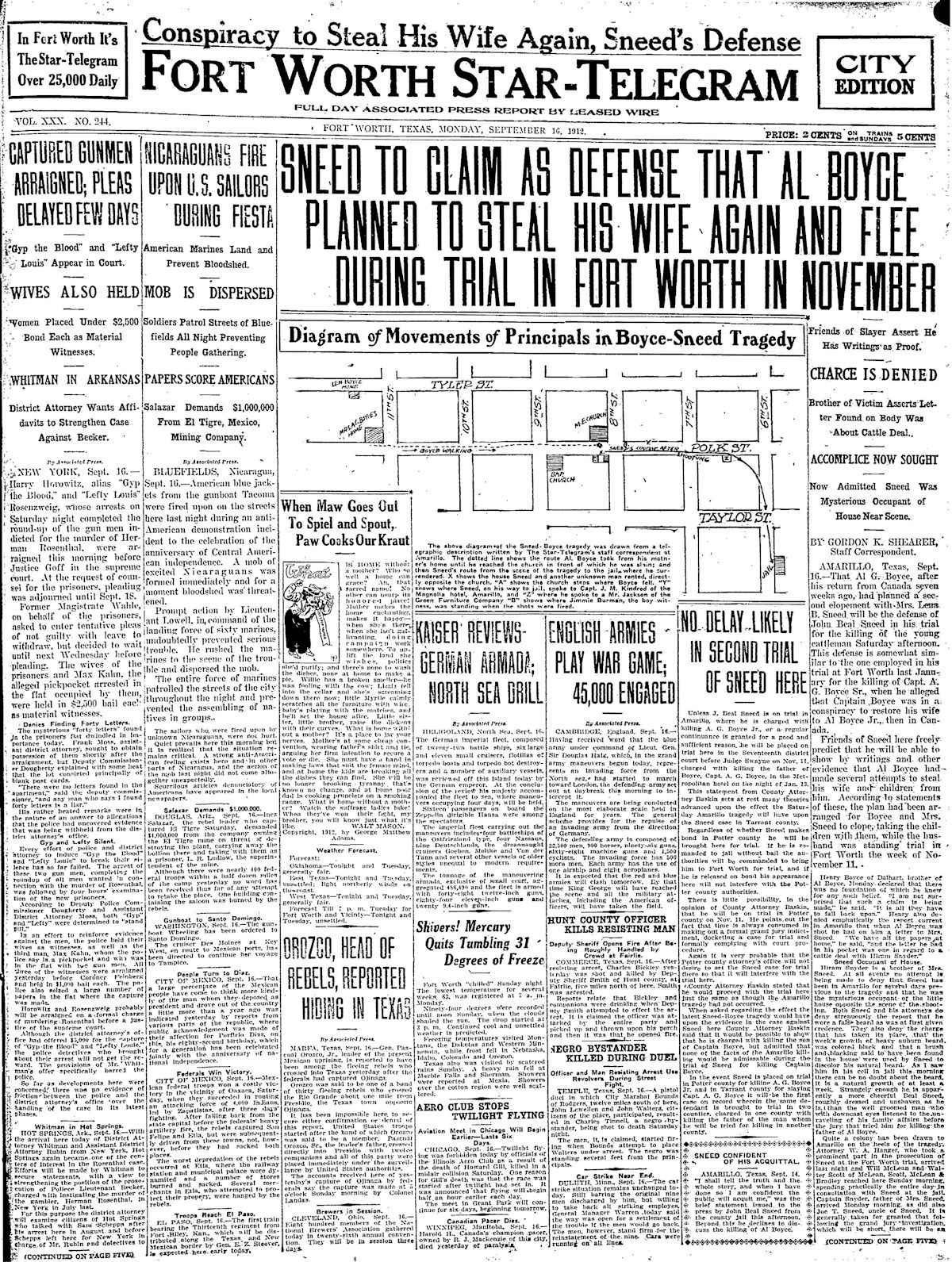

Sneed’s defense at his murder trial was that Boyce Sr. had been part of a conspiracy to unite Lena with Boyce Jr. (In the clip above note the headline about J. Frank Norris.)

Sneed’s defense at his murder trial was that Boyce Sr. had been part of a conspiracy to unite Lena with Boyce Jr. (In the clip above note the headline about J. Frank Norris.)

Sneed based his defense, in part, on the “unwritten law.”

According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

The Review adds: “Criminal defendants who could convince a jury that they killed in defense of the sanctity of their home, and the virtue of their women, were almost certain to be acquitted.” (But the unwritten law was lopsided: It was not as likely to protect a wife who killed her husband’s lover.)

The unwritten law was used as a “get out of jail free” card for homicide mostly from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. The unwritten law may not have been codified, but as a defense it could be as effective as any written law. For example, in addition to Sneed, these murder defendants invoked the unwritten law:

•In 1915 Fort Worth lawyer and aggrieved father Dee Estes pleaded the unwritten law after he killed a man arrested for molesting Estes’s daughter. Estes shot the suspect at the jail with police as witnesses! Estes was acquitted.

•In 1917 Will Jobe shot and killed Niles City policeman Tom Finch on the sidewalk outside Monnig’s Department Store as passersby watched. Jobe’s defense team showed that his wife had been unfaithful to him with Finch. Jobe was acquitted.

•Also in 1917 Reverend C. C. Reneau, jealous of one-legged W. N. Shaw’s attentions to Mrs. Reneau, fired his gun through a bedroom window and killed Shaw as Shaw was alone and buckling on his artificial leg. Reneau pleaded the unwritten law and was no-billed by a grand jury.

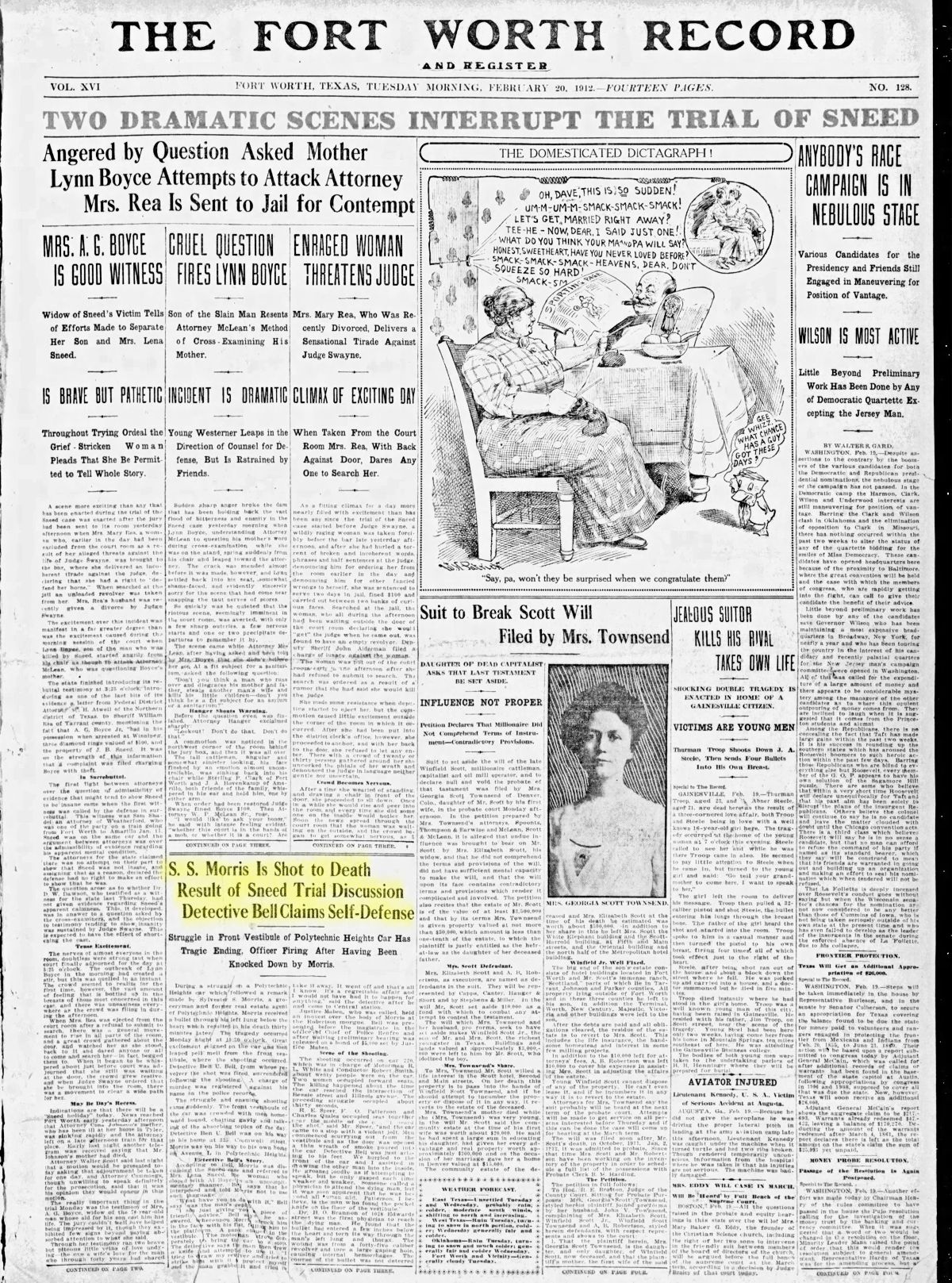

Sneed’s trial was the Cullen Davis trial of its time. Newspapers pronounced it “the greatest legal battle ever fought in Texas Courts,” “without precedent in Texas criminal history,” “the most noted murder trial in the state’s history.” Indeed, the trial generated intense interest across the United States and parts of Canada. Newspapers printed updates daily. The Star-Telegram reported, “So intense was the situation” that Judge James W. Swayne stationed deputy sheriffs at the doors of the courtroom to search each spectator for concealed weapons.

Thomas H. Thompson, newspaperman and author of two books on Amarillo history, wrote: “In Fort Worth, the trial produced controversy that led to violence. Four men were killed outside the courthouse, and women fought with hatpins in the courthouse halls and even in the courtroom.”

For example, the front page of the January 20, 1912 Star-Telegram—a page filled with Sneed trial coverage—contained this report: On the night of January 19, among the passengers riding home on a Polytechnic streetcar were grocer Sylvester S. Morris and Fort Worth police detective Ben U. Bell. The Star-Telegram later wrote that Bell said that as he and Morris were discussing the Sneed trial, Morris “referred to Mrs. Lena Sneed, the woman who eloped with Al Boyce, in an uncomplimentary manner. Bell says that he interposed and told Morris not to use such language.”

For example, the front page of the January 20, 1912 Star-Telegram—a page filled with Sneed trial coverage—contained this report: On the night of January 19, among the passengers riding home on a Polytechnic streetcar were grocer Sylvester S. Morris and Fort Worth police detective Ben U. Bell. The Star-Telegram later wrote that Bell said that as he and Morris were discussing the Sneed trial, Morris “referred to Mrs. Lena Sneed, the woman who eloped with Al Boyce, in an uncomplimentary manner. Bell says that he interposed and told Morris not to use such language.”

“What have you to do with it?” Morris asked Bell.

“I’m just giving you a piece of friendly advice,” Bell said.

Morris then hit Bell in the face with his fist, knocking Bell to the floor.

Morris then drew a knife and tried to stab Bell. Bell drew his .45-caliber revolver with the intent of striking Morris with it to disarm him, but Morris grabbed the gun. As the two men grappled, the gun discharged. Morris was fatally wounded.

Bell was indicted for murder, but the charge was later dropped.

The murder trial of John Beal Sneed ended in a hung jury.

The murder trial of John Beal Sneed ended in a hung jury.

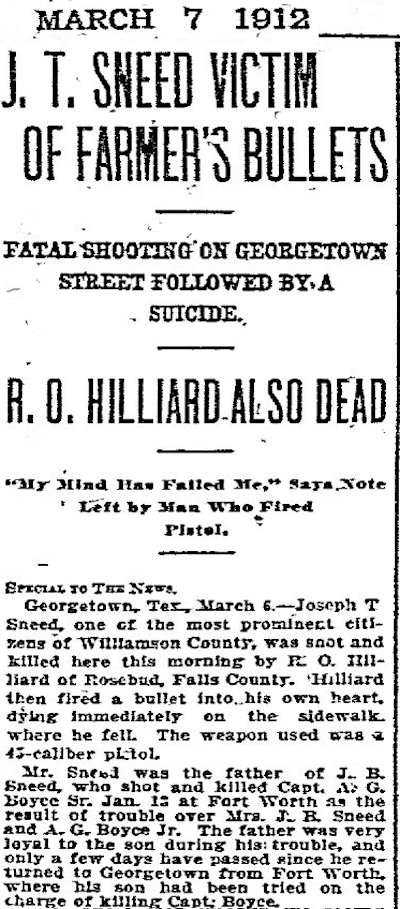

The feud spread. In March 1912 Sneed’s father was killed by a tenant farmer who was believed to be associated with the Boyces. The farmer then committed suicide.

The feud spread. In March 1912 Sneed’s father was killed by a tenant farmer who was believed to be associated with the Boyces. The farmer then committed suicide.

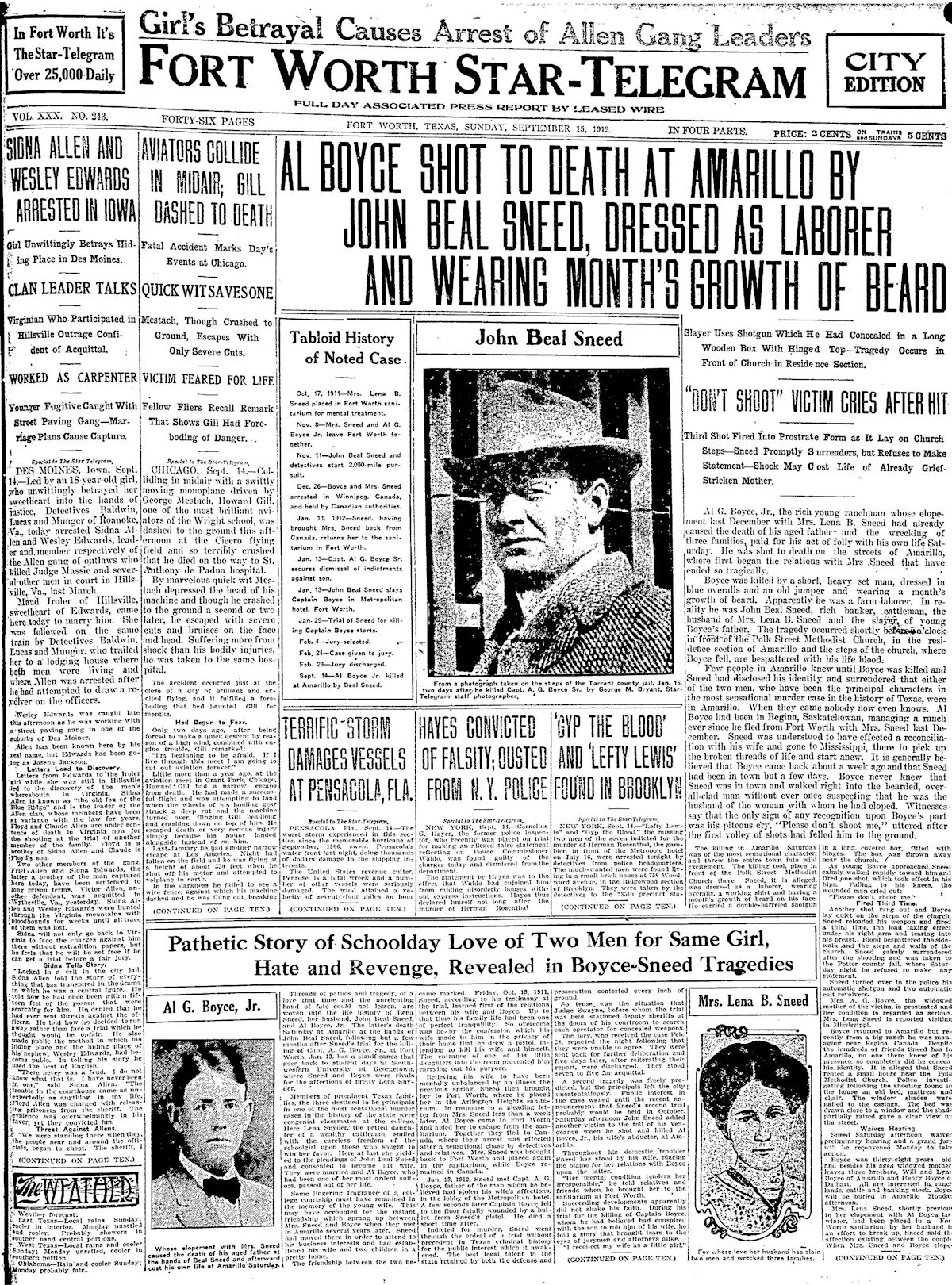

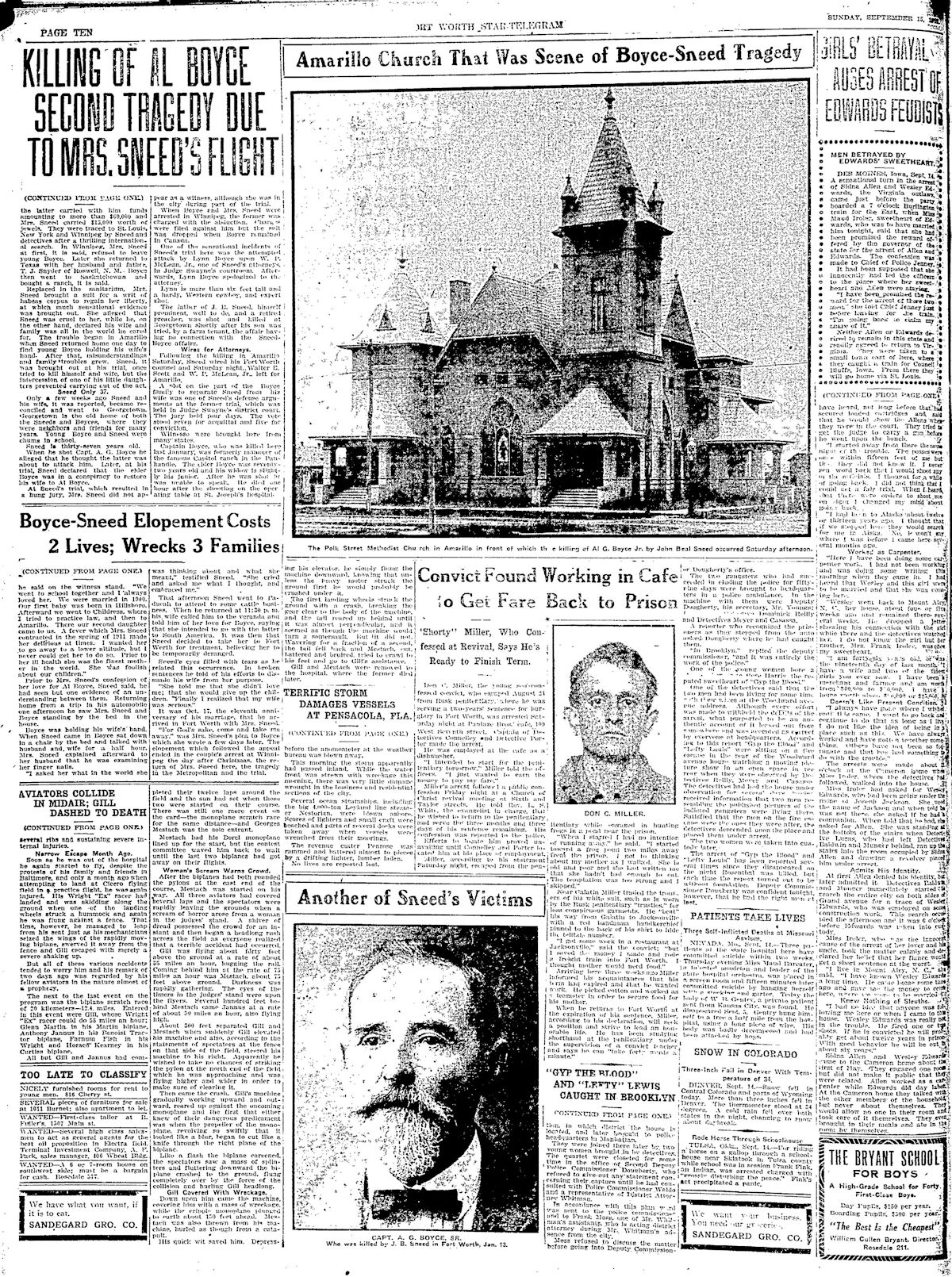

On September 14, 1912 John Beal Sneed, disguised and lying in wait with a shotgun, shot and killed Boyce Jr. as Boyce was walking in front of Polk Street Methodist Church in Amarillo. Sneed had watched for two weeks from a house nearby, waiting to see Boyce unaccompanied by his brother Lynn. After shooting Boyce, Sneed walked to the courthouse and surrendered. Boyce Jr. had just returned from Canada and was living with his mother near the scene of the shooting. Sneed and wife Lena had been living in Mississippi and had just returned to Amarillo.

On September 14, 1912 John Beal Sneed, disguised and lying in wait with a shotgun, shot and killed Boyce Jr. as Boyce was walking in front of Polk Street Methodist Church in Amarillo. Sneed had watched for two weeks from a house nearby, waiting to see Boyce unaccompanied by his brother Lynn. After shooting Boyce, Sneed walked to the courthouse and surrendered. Boyce Jr. had just returned from Canada and was living with his mother near the scene of the shooting. Sneed and wife Lena had been living in Mississippi and had just returned to Amarillo.

Déjà vu. Where have we seen those photos before?

Déjà vu. Where have we seen those photos before?

Page 2 of the September 15 Star-Telegram.

Page 2 of the September 15 Star-Telegram.

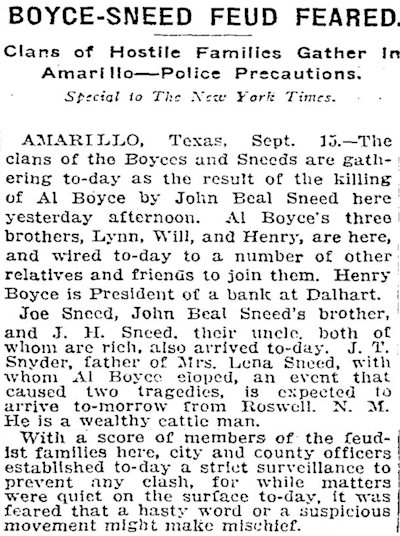

A story in the New York Times on September 15 reported ominously that the Sneed and Boyce “clans” were gathering in Amarillo after the killing of another Boyce by Sneed.

A story in the New York Times on September 15 reported ominously that the Sneed and Boyce “clans” were gathering in Amarillo after the killing of another Boyce by Sneed.

In his murder trial for the killing of Boyce Jr., John Beal Sneed’s defense was that he had feared that Boyce would elope with Lena again. He again invoked the unwritten law.

In his murder trial for the killing of Boyce Jr., John Beal Sneed’s defense was that he had feared that Boyce would elope with Lena again. He again invoked the unwritten law.

Note the headline “No Delay Likely in Second Trial of Sneed Here.” That refers to Sneed’s retrial for killing Boyce Sr. It’s not often that a single newspaper page contains stories about a man facing trials for killing a father and a son in separate incidents.

Also note the diagram of the scene of the killing of Jr.

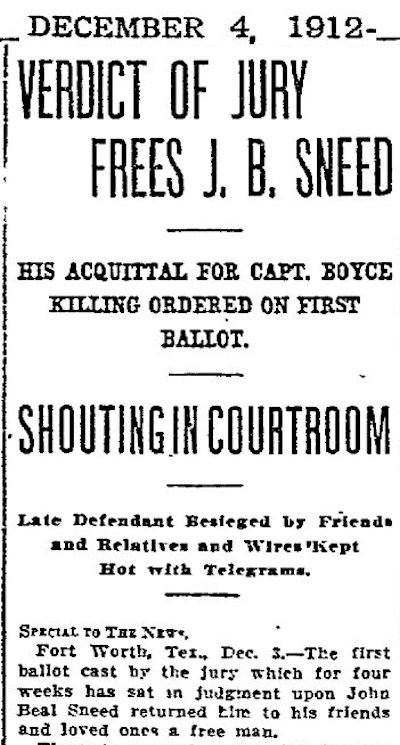

In a retrial in December 1912 Sneed was acquitted of killing Boyce Sr. The jury found the killing to be justifiable homicide. The unwritten law had prevailed.

In a retrial in December 1912 Sneed was acquitted of killing Boyce Sr. The jury found the killing to be justifiable homicide. The unwritten law had prevailed.

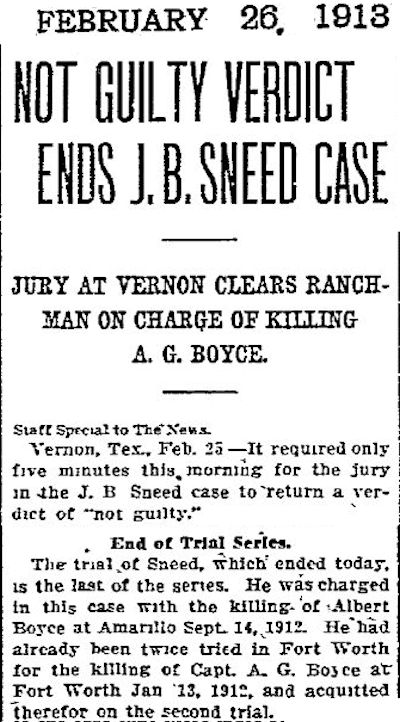

In February 1913 Sneed was acquitted of killing Boyce Jr. The jury deliberated five minutes.

In February 1913 Sneed was acquitted of killing Boyce Jr. The jury deliberated five minutes.

According to the book Death Lore: Texas Rituals, Superstitions, and Legends of the Hereafter, when reporters asked how the jury could acquit Sneed, jury foreman James D. Crane responded by saying, ‘The best answer is because this is Texas. We believe in Texas a man has the right and the obligation to safeguard the honor of his home, even if he must kill the person responsible.’”

The unwritten law had prevailed again.

The twice-acquitted Sneed, reunited with Lena, moved to Paducah, where he owned a cotton farm and ranch. But Sneed’s land speculation resulted in financial straits. In 1922 a federal court convicted him of bribing a juror in a lawsuit. Sneed was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth. In Sneed’s absence, C. B. Berry, a Paducah cotton farmer and grocer, in 1922 shot and killed Wood Barton, Sneed’s son-in-law. Berry was acquitted.

The twice-acquitted Sneed, reunited with Lena, moved to Paducah, where he owned a cotton farm and ranch. But Sneed’s land speculation resulted in financial straits. In 1922 a federal court convicted him of bribing a juror in a lawsuit. Sneed was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth. In Sneed’s absence, C. B. Berry, a Paducah cotton farmer and grocer, in 1922 shot and killed Wood Barton, Sneed’s son-in-law. Berry was acquitted.

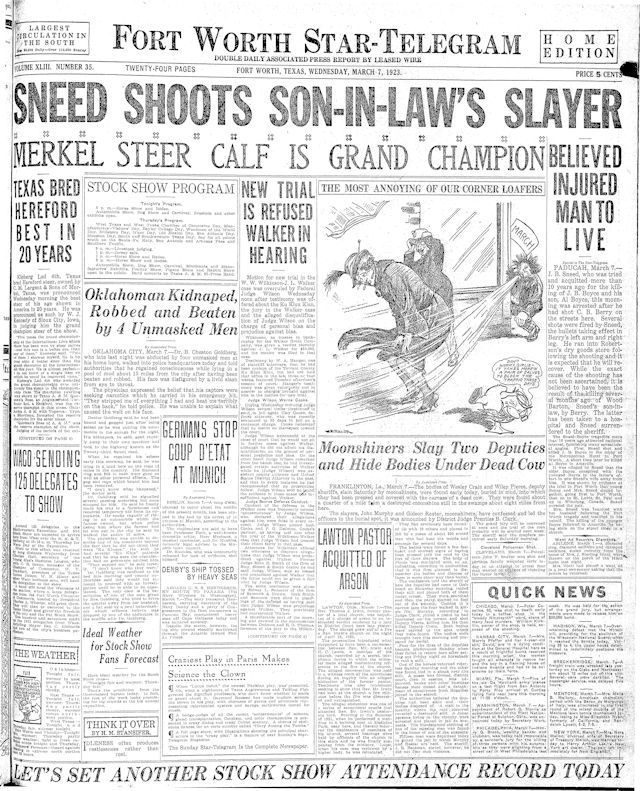

By March 1923 Sneed was out of prison. Brooding about Berry’s acquittal in the killing of son-in-law Wood Barton, Sneed retaliated by shooting Berry. Five times. Berry survived.

By March 1923 Sneed was out of prison. Brooding about Berry’s acquittal in the killing of son-in-law Wood Barton, Sneed retaliated by shooting Berry. Five times. Berry survived.

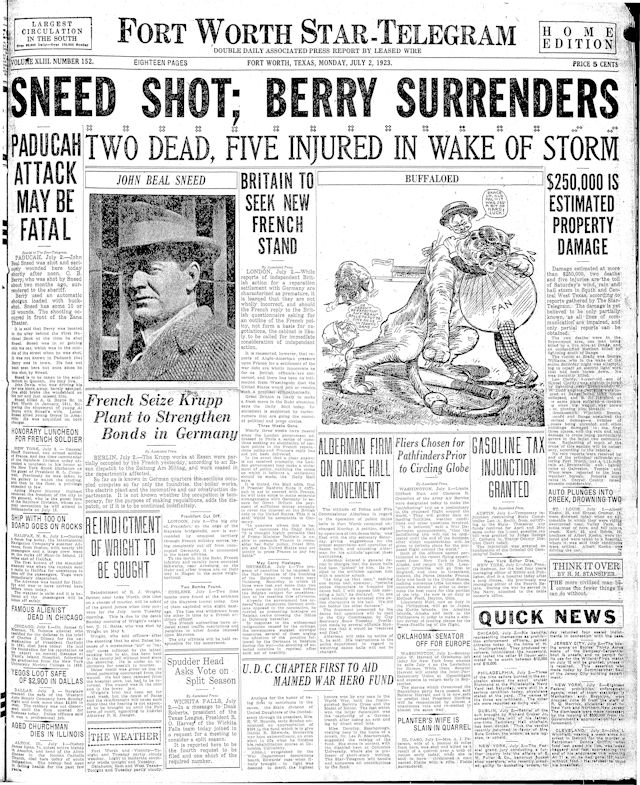

In July 1923 it was Berry’s turn: He peppered Sneed with buckshot. Sneed survived.

In July 1923 it was Berry’s turn: He peppered Sneed with buckshot. Sneed survived.

This front page marks the third time that photo of Sneed had appeared on the front page of the Star-Telegram.

At their trials for shooting each other, both Berry and Sneed were . . . wait for it . . . acquitted. That brings our total to six confirmed shootings, four of them fatal, and no convictions.

By then Sneed and Lena felt that a change of scenery was advisable. They left Paducah and moved to Dallas. Sneed invested in the east Texas oilfield and again prospered. Husband and wife lived well for more than thirty years.

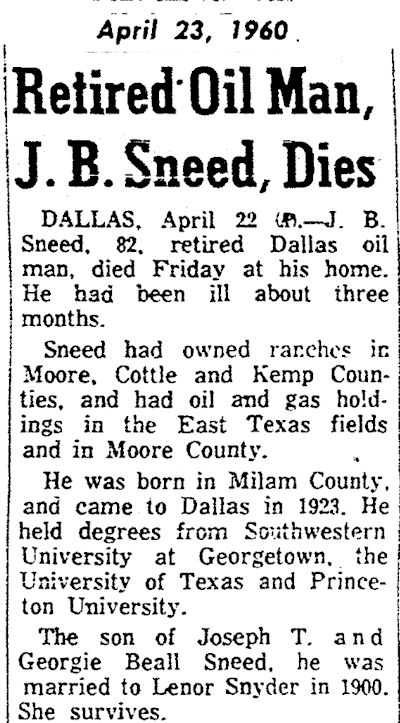

In fact, by the time John Beal Sneed died in 1960, he and Lena had kept a bedeviled marriage together for sixty years! His obituary in the Star-Telegram gives no hint of a life ruled by romance and revenge and of a bloody feud ignited in the lobby of the Metropolitan Hotel. But unwittingly the obituary spoke volumes about the life of Lena with a two-word sentence:

In fact, by the time John Beal Sneed died in 1960, he and Lena had kept a bedeviled marriage together for sixty years! His obituary in the Star-Telegram gives no hint of a life ruled by romance and revenge and of a bloody feud ignited in the lobby of the Metropolitan Hotel. But unwittingly the obituary spoke volumes about the life of Lena with a two-word sentence:

“She survives.”

In fact, Lena survived until 1966. Husband and wife are buried side by side in Sparkman Hillcrest Cemetery in Dallas.

In fact, Lena survived until 1966. Husband and wife are buried side by side in Sparkman Hillcrest Cemetery in Dallas.

The Metropolitan Hotel: Mahogany and Homicide (Part 2)

The Metropolitan Hotel: Mahogany and Homicide (Part 3)

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

You mean rich white men.

Point well taken. Even “rich” was not a necessary trait.

WOW!!

In a word, yes. It was hard for a man to get convicted of homicide back then.