Even if you’ve lived in Fort Worth only a short time, you’ve probably crossed the University Drive bridge over the Clear Fork of the Trinity River a few times. If you’ve lived in Fort Worth a long time, you’ve crossed that bridge many times.

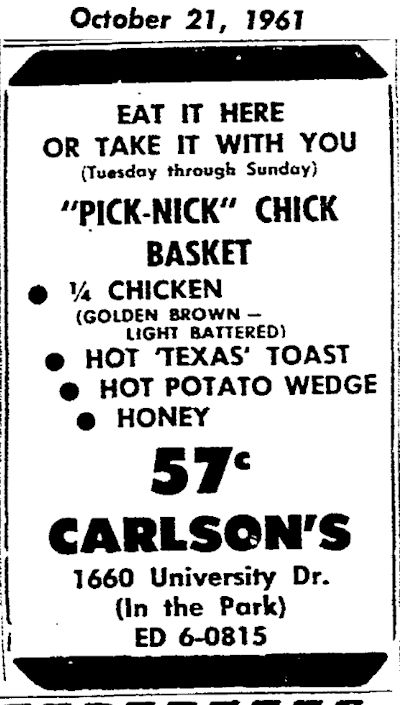

Perhaps to eat at Carlson’s or to attend the Colonial NIT or to ride the Forest Park miniature train.

Perhaps to eat at Carlson’s or to attend the Colonial NIT or to ride the Forest Park miniature train.

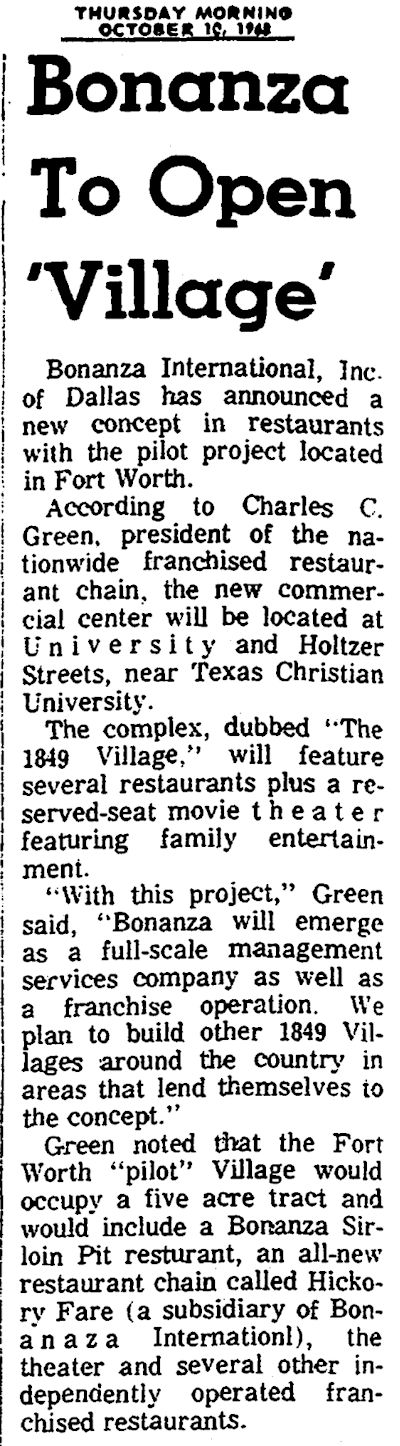

Or to stroll through 1849 Village.

Or to stroll through 1849 Village.

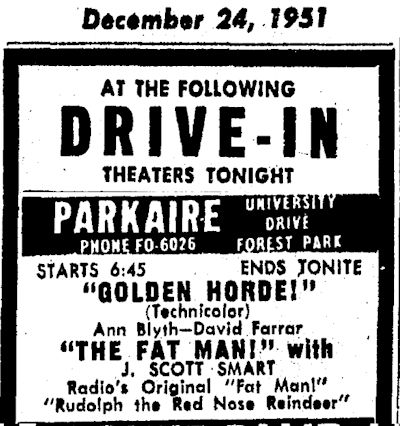

Perhaps to see a movie at the Parkaire drive-in theater. (Note the FO phone exchange.)

Perhaps to see a movie at the Parkaire drive-in theater. (Note the FO phone exchange.)

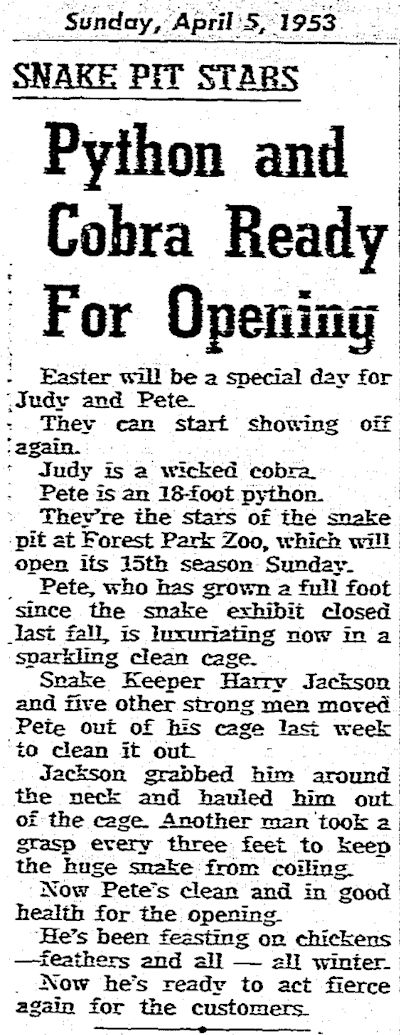

Or perhaps to go to the zoo to see Pete the python. (Seventeen months after this report, Pete would take his show on the road.)

Or perhaps to go to the zoo to see Pete the python. (Seventeen months after this report, Pete would take his show on the road.)

And as you drove over that bridge you may have noticed something . . . odd about it.

This is the view looking north at the southbound lanes: a through truss span.

This is the view looking north at the southbound lanes: a through truss span.

This is the view looking north at the northbound lanes: a pony truss span.

This is the view looking north at the northbound lanes: a pony truss span.

This is the view looking north from the center of the bridge: just a road bed edged with guardrails and supported by concrete beams and piers.

This is the view looking north from the center of the bridge: just a road bed edged with guardrails and supported by concrete beams and piers.

And this is the side view.

And this is the side view.

Just look at that bridge. It looks as if someone received an . . .

Erector Set for Christmas and set out to span the river but ran out of parts less than halfway across. (1922 ad from Wikipedia.)

Erector Set for Christmas and set out to span the river but ran out of parts less than halfway across. (1922 ad from Wikipedia.)

The University Drive bridge is an architectural mash-up, a Frankenbridge.

In fact, although we think of it as the University Drive bridge (singular), it actually consists of two bridges with a gap between. Further, each bridge consists of two parts: an original span and an extension.

In fact, although we think of it as the University Drive bridge (singular), it actually consists of two bridges with a gap between. Further, each bridge consists of two parts: an original span and an extension.

Yes, the University Drive bridge is a fourfer, and there is a story behind its four parts—the story of Fort Worth’s response to (1) growth and (2) natural disaster.

The residents of any city on a river face the challenge of getting from point A to point B when point B is on the other side of the river. In the beginning Fort Worth residents forded the river on foot or hoof or wagon at points of low water. At deeper water they crossed on rafts and ferries. They built bridges of timber and then lumber and then iron and cable and finally concrete and steel.

But safe, sturdy bridges are expensive. As late as 1907, when Fort Worth had a population of about 68,000, the city had only nine vehicular bridges (and seven rail bridges) over the two forks of the Trinity River. The Clear Fork in 1907 had three bridges: on Franklin Street (White Settlement Road today), Arlington Heights Boulevard (West 7th Street today), and Granbury Road (West Vickery today). Today I count twenty-eight vehicular bridges over the river just from the Loop inward, fifteen of them on the Clear Fork.

By 1936 Fort Worth had a population of about 170,000, but the Clear Fork had only two additional bridges: on Henderson Street and on Rogers Road north of TCU. That means that in 1936 people in southwest Fort Worth (TCU, Seminary Hill, Park Hill, Shaw Heights, Frisco Heights, Hubbard Highlands, etc.) wanting to go to Arlington Heights, the nascent cultural district, or Trinity Park and Rock Springs Park (today’s Botanic Garden) had to cross the river on Rogers Road or go northeast to the West 7th Street bridge.

By 1936 Fort Worth had a population of about 170,000, but the Clear Fork had only two additional bridges: on Henderson Street and on Rogers Road north of TCU. That means that in 1936 people in southwest Fort Worth (TCU, Seminary Hill, Park Hill, Shaw Heights, Frisco Heights, Hubbard Highlands, etc.) wanting to go to Arlington Heights, the nascent cultural district, or Trinity Park and Rock Springs Park (today’s Botanic Garden) had to cross the river on Rogers Road or go northeast to the West 7th Street bridge.

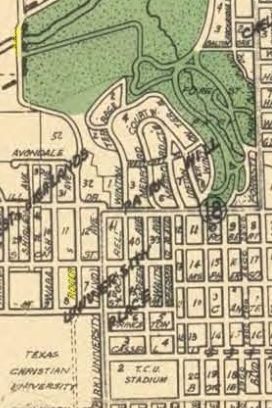

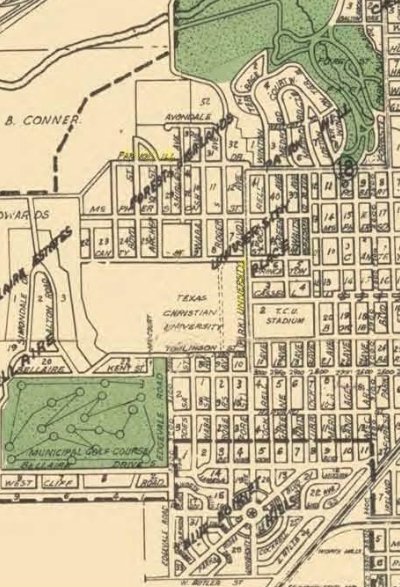

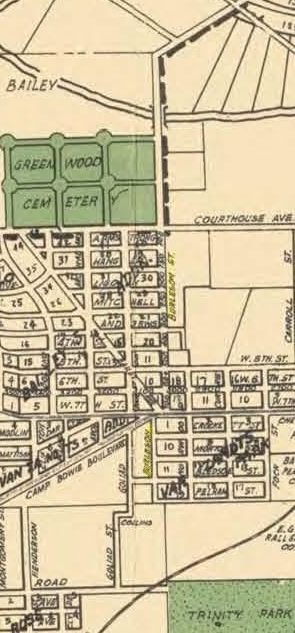

University Drive extended only from just south of Bluebonnet traffic circle north to Park Hill Drive. (Note the municipal golf course.)

University Drive extended only from just south of Bluebonnet traffic circle north to Park Hill Drive. (Note the municipal golf course.)

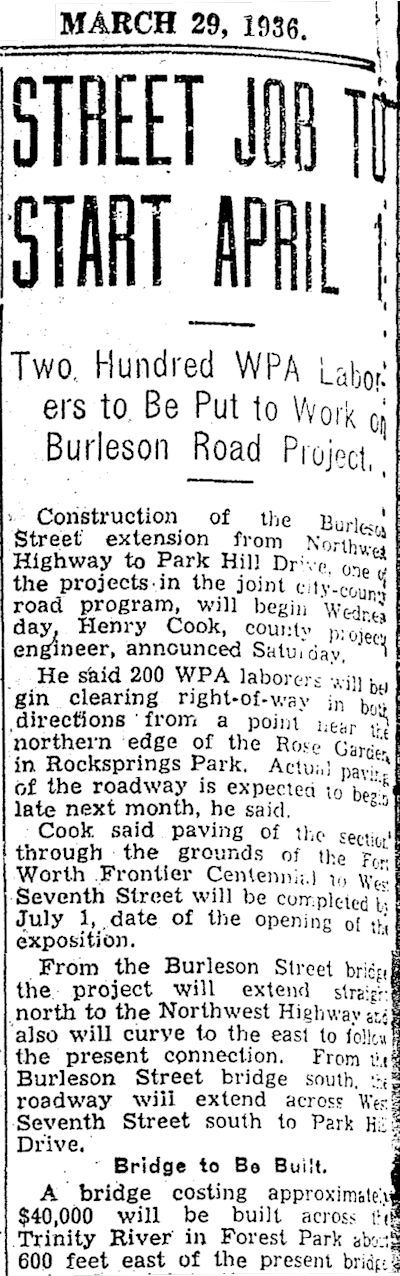

But in March 1936, just four months before Fort Worth’s Frontier Centennial was to begin, the city and county announced plans for an ambitious street project for the West Side. With a little help from the federal Works Progress Administration, Burleson Street would be extended, the Star-Telegram reported, from Northwest Highway (Jacksboro Highway) south to University Drive at Park Hill Drive.

But in March 1936, just four months before Fort Worth’s Frontier Centennial was to begin, the city and county announced plans for an ambitious street project for the West Side. With a little help from the federal Works Progress Administration, Burleson Street would be extended, the Star-Telegram reported, from Northwest Highway (Jacksboro Highway) south to University Drive at Park Hill Drive.

The southern extension of Burleson Street would border the Frontier Centennial grounds on the east (where Casa Manana and the Will Rogers complex are today), and finishing that part of the southern extension before the big wingding began was a priority. The southern extension would then pass through Rock Springs Park, Trinity Park, and Forest Park and then through unincorporated land to University Drive.

In the clip “from the Burleson Street bridge south” refers to an existing bridge over the West Fork of the Trinity at Greenwood Cemetery.

A $40,000 ($700,000 today) bridge would be built over the Clear Fork in Forest Park. The “present bridge” refers to the Rogers Road bridge.

This 1929 map shows Burleson Street. The Star-Telegram story implies that Burleson Street was being extended to the north, but maps such as this one and other news articles indicate that the street already ran from Pelham Street (West Lancaster Avenue today) northwest to Jacksboro Highway. So, apparently the 1936 project paved, widened, or otherwise improved the existing Burleson Street. Also a new bridge was built over the West Fork of the Trinity at Greenwood Cemetery.

This 1929 map shows Burleson Street. The Star-Telegram story implies that Burleson Street was being extended to the north, but maps such as this one and other news articles indicate that the street already ran from Pelham Street (West Lancaster Avenue today) northwest to Jacksboro Highway. So, apparently the 1936 project paved, widened, or otherwise improved the existing Burleson Street. Also a new bridge was built over the West Fork of the Trinity at Greenwood Cemetery.

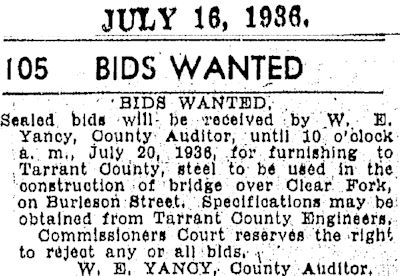

In July, just two days before the Frontier Centennial began, the county advertised for bids for steel for the bridge to carry the southern extension of Burleson Street over the Clear Fork of the Trinity.

In July, just two days before the Frontier Centennial began, the county advertised for bids for steel for the bridge to carry the southern extension of Burleson Street over the Clear Fork of the Trinity.

The two-lane University Drive bridge was finished in late 1937. Art deco was a popular architectural style at the time.

The two-lane University Drive bridge was finished in late 1937. Art deco was a popular architectural style at the time.

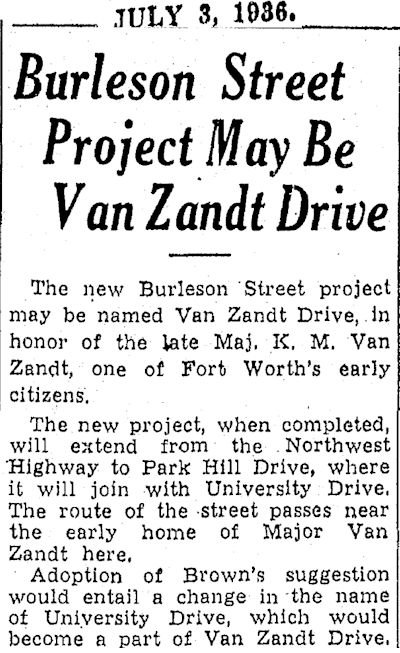

City Councilman A. C. Brown proposed renaming University Drive and the extended Burleson Street after civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. But rather than rename University Drive “Van Zandt Drive,” the city renamed all of the extended Burleson Street “University Drive.”

City Councilman A. C. Brown proposed renaming University Drive and the extended Burleson Street after civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. But rather than rename University Drive “Van Zandt Drive,” the city renamed all of the extended Burleson Street “University Drive.”

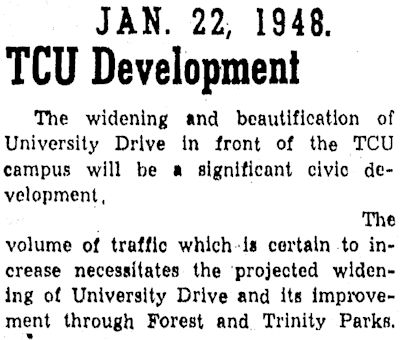

Fast-forward to 1948. Fort Worth’s population was now above 250,000. The Star-Telegram in an editorial said that planned widening of University Drive at TCU would necessitate widening of the street farther north.

Fast-forward to 1948. Fort Worth’s population was now above 250,000. The Star-Telegram in an editorial said that planned widening of University Drive at TCU would necessitate widening of the street farther north.

So, in 1952 University Drive from Crestline Road to Park Hill Drive was widened from two to four lanes. That widening necessitated erecting a second two-lane bridge next to the 1937 bridge over the Clear Fork. This 1952 aerial photo shows the 1937 bridge and University Drive as it was being widened north of the river before the new span was built. Afterward the 1937 span carried only the southbound lanes, and the new span carried only the northbound lanes.

So, in 1952 University Drive from Crestline Road to Park Hill Drive was widened from two to four lanes. That widening necessitated erecting a second two-lane bridge next to the 1937 bridge over the Clear Fork. This 1952 aerial photo shows the 1937 bridge and University Drive as it was being widened north of the river before the new span was built. Afterward the 1937 span carried only the southbound lanes, and the new span carried only the northbound lanes.

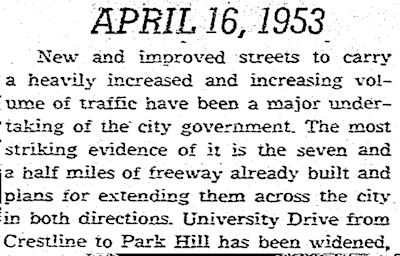

In 1953 a Star-Telegram editorial praised the widening of University Drive. That widening included the new two-lane span over the Clear Fork.

In 1953 a Star-Telegram editorial praised the widening of University Drive. That widening included the new two-lane span over the Clear Fork.

The 1952 span was given an art deco flourish to match the style of the 1937 span.

The 1952 span was given an art deco flourish to match the style of the 1937 span.

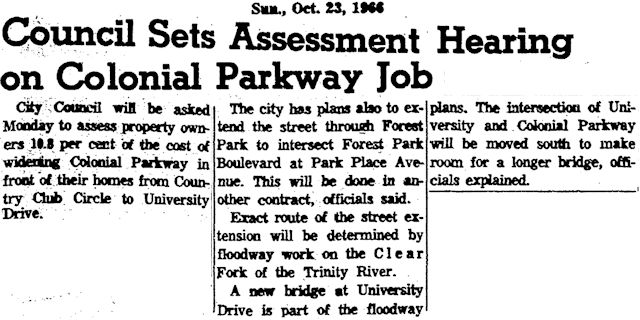

Fast-forward to 1966. After addition of the 1952 span, the University Drive bridge was wide enough. But in the 1960s the ambitious Trinity River floodway project, begun in the 1950s after the flood of 1949, caught up with the Clear Fork. Widening of the Clear Fork channel in the late 1960s rendered both University Drive spans too short, so extensions were added on their north end. (The lanes also were restriped from two to three sometime between 1956 and 1963.)

Fast-forward to 1966. After addition of the 1952 span, the University Drive bridge was wide enough. But in the 1960s the ambitious Trinity River floodway project, begun in the 1950s after the flood of 1949, caught up with the Clear Fork. Widening of the Clear Fork channel in the late 1960s rendered both University Drive spans too short, so extensions were added on their north end. (The lanes also were restriped from two to three sometime between 1956 and 1963.)

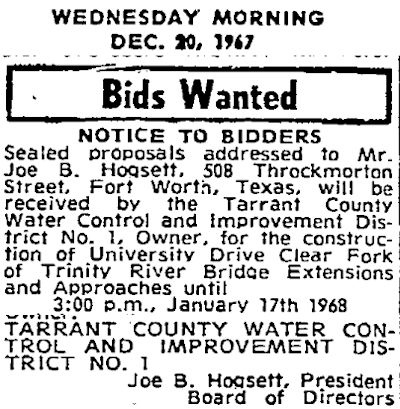

The extensions were completed by 1968.

The extensions were completed by 1968.

Before and after: A 1952 aerial photo and a contemporary aerial photo show how much the Clear Fork was widened and straightened on both sides of University Drive.

Before and after: A 1952 aerial photo and a contemporary aerial photo show how much the Clear Fork was widened and straightened on both sides of University Drive.

Likewise, the Forest Park miniature train (1959) originally crossed the river on a bridge just east of the 1952 University Drive span until widening of the Clear Fork rendered the rail bridge too short. A new rail bridge was installed downstream over the new channel in 1968, and the original bridge was relocated downstream to carry the train over the mouth of the old channel.

Likewise, the Forest Park miniature train (1959) originally crossed the river on a bridge just east of the 1952 University Drive span until widening of the Clear Fork rendered the rail bridge too short. A new rail bridge was installed downstream over the new channel in 1968, and the original bridge was relocated downstream to carry the train over the mouth of the old channel.

A concrete footing of the 1959 rail bridge remains beside the 1952 span.

A concrete footing of the 1959 rail bridge remains beside the 1952 span.

The four-part University Drive Frankenbridge today.

The four-part University Drive Frankenbridge today.

(And if the fact that a major north-south thoroughfare such as University Drive did not cross the Clear Fork until 1937 is surprising, a major east-west thoroughfare can top that. The east and west sections of Lancaster Avenue remained separated by the Clear Fork until the West Lancaster Avenue bridge opened in 1939.)

Wow! Another great article, Mike!

Sadly, I’ve never noticed the differences before, and I have passed over those bridges easily a thousand times.

Thanks, Scott. More Cowtown microhistory. To be honest, I first noticed the odd configuration of the bridge while passing under it from the side so many times on the Trinity Trails. Each time I’d pass under it, I’d say to myself, “I gotta look into that. That bridge has a story to tell.”