Calloway Cemetery

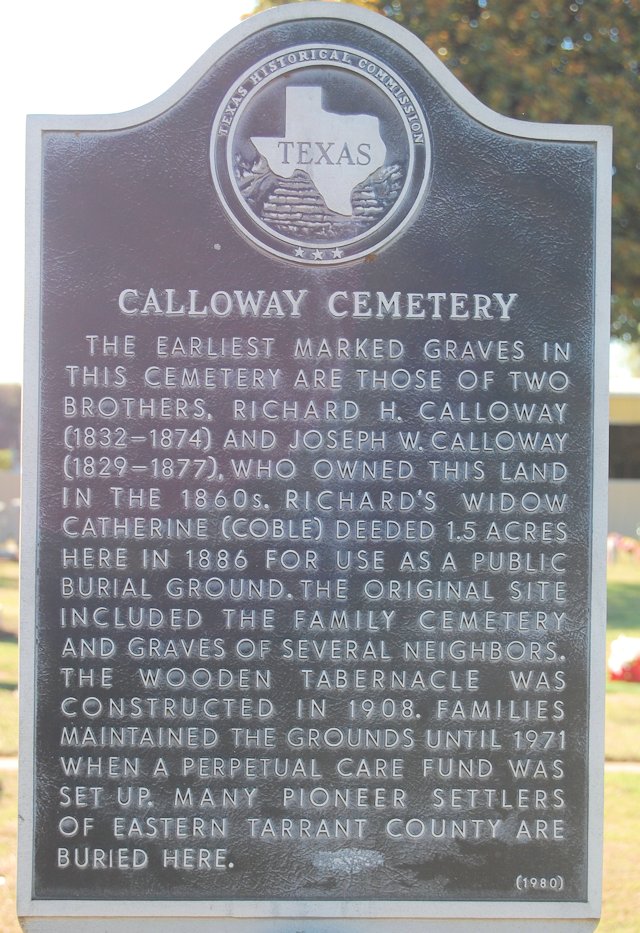

The story of little Calloway Cemetery is the story of many a pocket cemetery (see Part 1): It began service in the nineteenth century on farmland in the country but in the twenty-first century hunkers in the city, surrounded by concrete and commerce.

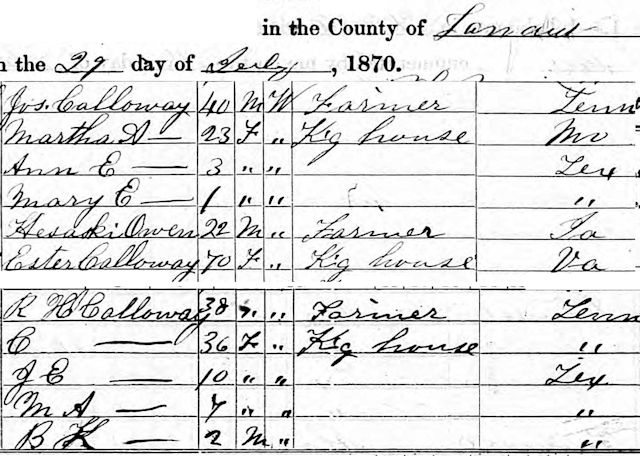

Now engulfed by heavy industry in south Euless, Calloway Cemetery was established on farmland settled in the 1860s by two brothers from Tennessee: Richard and Joseph Calloway. To the south is Calloway Lake, site of Bird’s Fort.

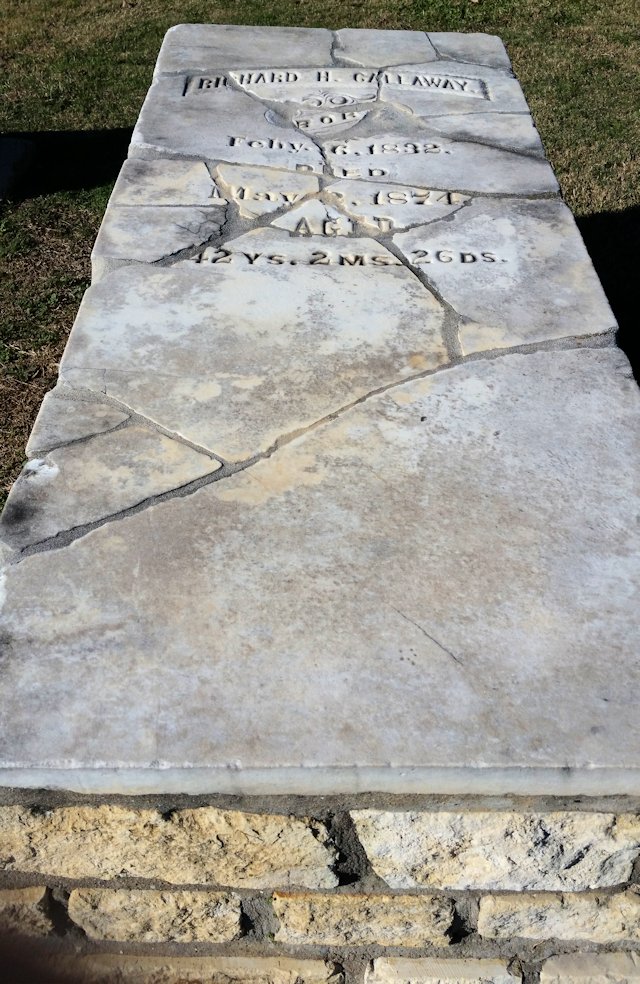

Richard’s altar tomb was the cemetery’s first burial in 1874. Then came more Calloway burials and some of neighboring farm families. The earliest birth date recorded among those buried here is 1822.

Richard’s altar tomb was the cemetery’s first burial in 1874. Then came more Calloway burials and some of neighboring farm families. The earliest birth date recorded among those buried here is 1822.

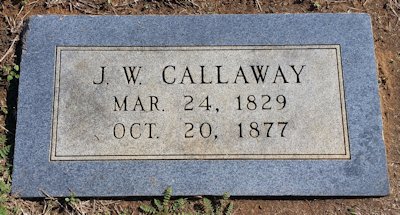

This tombstone of brother Joseph surely is a replacement of the original.

This tombstone of brother Joseph surely is a replacement of the original.

After Richard and Joseph died, Richard’s wife Catherine in 1886 deeded the cemetery for public use.

After Richard and Joseph died, Richard’s wife Catherine in 1886 deeded the cemetery for public use.

Homemade tombstones. Brothers Albert and Alford, born on Christmas Eve, did not live to see their first Fourth of July.

Homemade tombstones. Brothers Albert and Alford, born on Christmas Eve, did not live to see their first Fourth of July.

Three Himes families lived near Joseph Calloway.

The cemetery has several graves whose occupants are not identified.

The cemetery has several graves whose occupants are not identified.

Today Calloway Cemetery (yellow rectangle) is surrounded by petroleum tank farms, gravel quarries, concrete plants, and railroad sidings. The concrete plants and an ant-trail procession of big trucks rumbling along Calloway Cemetery Road ensure that the cemetery has no shortage of dust to dust.

Today Calloway Cemetery (yellow rectangle) is surrounded by petroleum tank farms, gravel quarries, concrete plants, and railroad sidings. The concrete plants and an ant-trail procession of big trucks rumbling along Calloway Cemetery Road ensure that the cemetery has no shortage of dust to dust.

Isham Cemetery

Isham Cemetery is on John T. White Road on the East Side.

Isham Cemetery is on John T. White Road on the East Side.

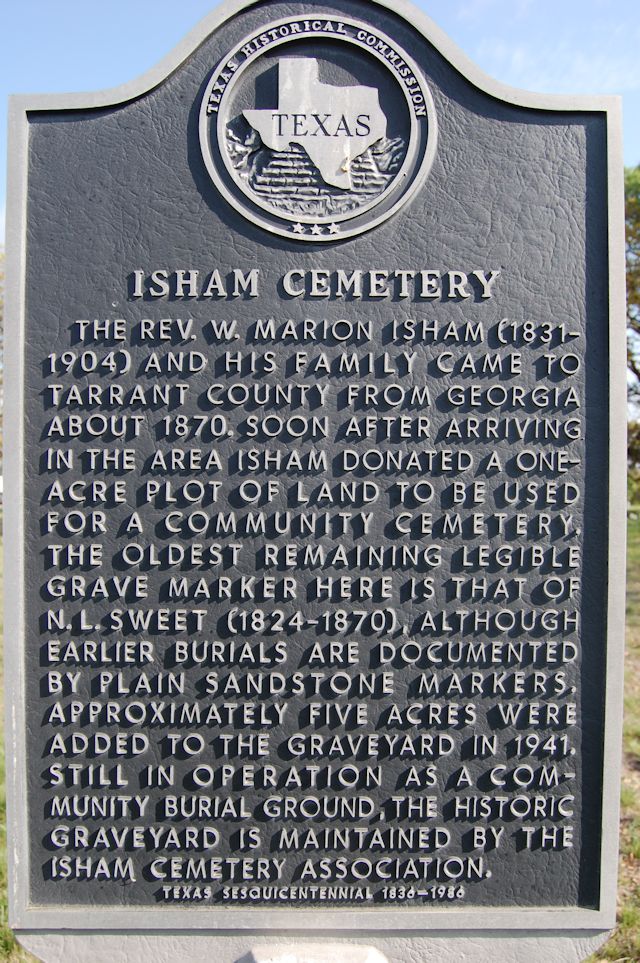

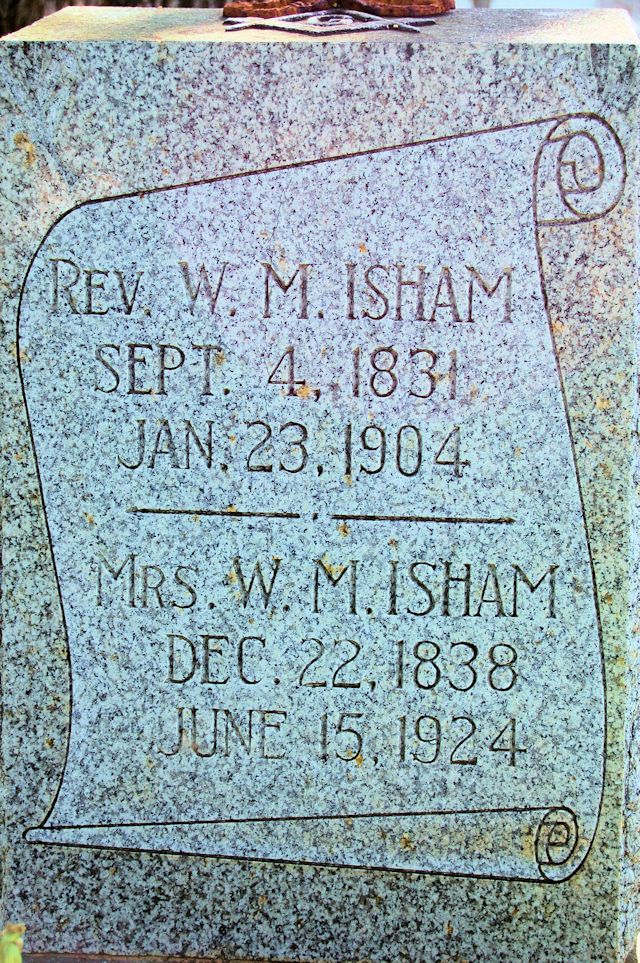

Reverend Washington Marion Isham, pastor of Isham Chapel Methodist Protestant Church, founded Isham Cemetery in 1870. The cemetery is still active. Reverend Isham lived near his namesake cemetery, but his chapel was two miles northeast near Hurst.

In this photo of the original Isham Chapel, Reverend Isham is on the far right. (Photo from Tarrant County College, Northeast, Heritage Room.)

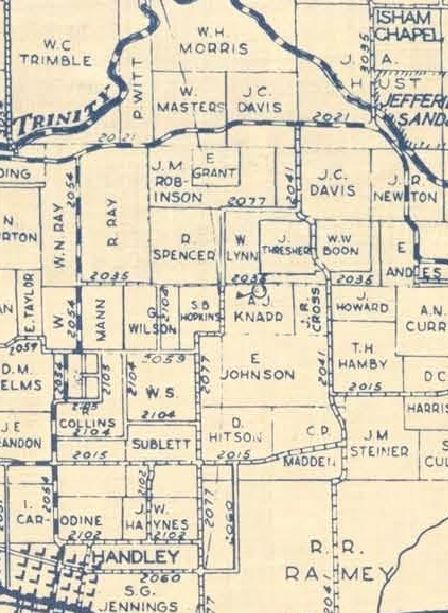

Isham Chapel appears on this 1943 county map. In 1952 the church moved and today is First United Methodist Church of Hurst.

Isham Chapel appears on this 1943 county map. In 1952 the church moved and today is First United Methodist Church of Hurst.

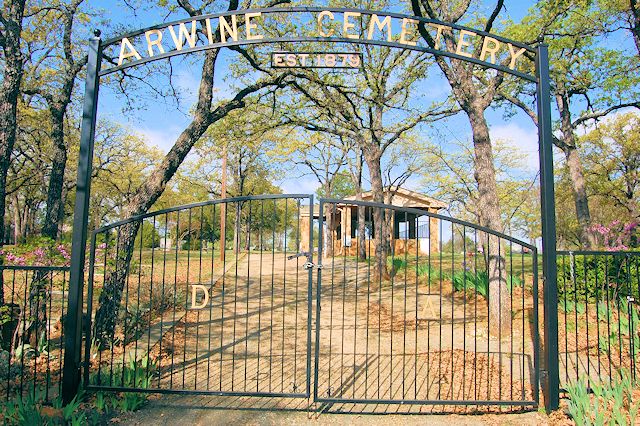

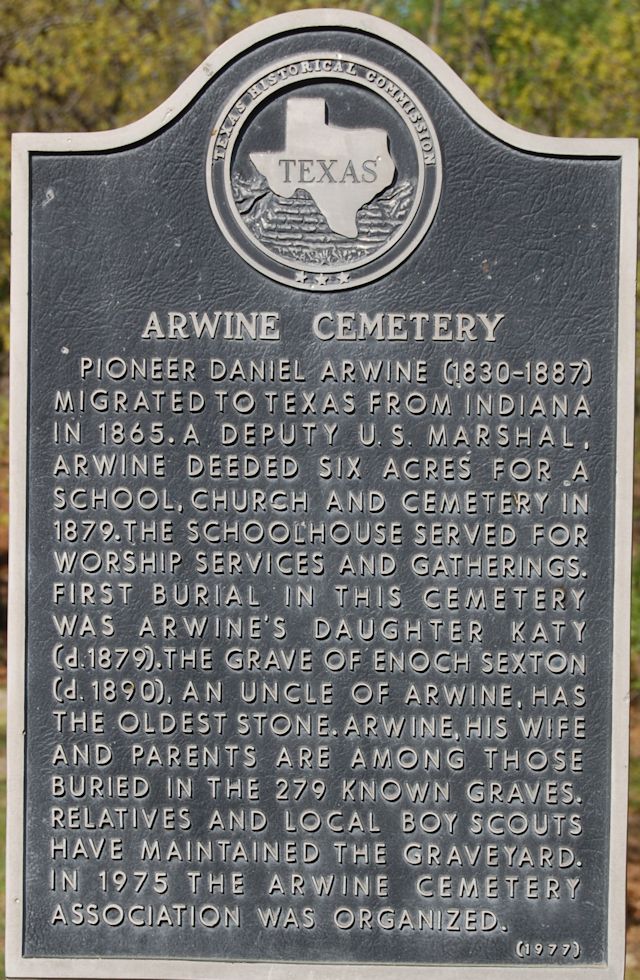

Arwine Cemetery

Arwine Cemetery is located on a residential street in Hurst.

Arwine Cemetery is located on a residential street in Hurst.

Daniel Arwine was born in Tennessee and fought for the Union in the Indiana Infantry during the Civil War. He immigrated to Texas in 1865 and settled in the Hurst area. Arwine became a deputy U.S. marshal.

Daniel Arwine was born in Tennessee and fought for the Union in the Indiana Infantry during the Civil War. He immigrated to Texas in 1865 and settled in the Hurst area. Arwine became a deputy U.S. marshal.

In 1879 Arwine and wife Julia deeded six acres for a school, a church, and a cemetery.

In 1879 Arwine and wife Julia deeded six acres for a school, a church, and a cemetery.

This 1895 map shows an Arwine homestead and the Arwine school. Note also two Hurst family homesteads.

This 1895 map shows an Arwine homestead and the Arwine school. Note also two Hurst family homesteads.

Daniel and Julia’s daughter Katy selected the cemetery site. A few months later Katy died and became the first person buried in Arwine Cemetery.

Arwine School (photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room).

Arwine School (photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room).

The family of James and Hattie Arwine Anderson (1868-1960) (photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room).

The family of James and Hattie Arwine Anderson (1868-1960) (photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room).

Hattie was a daughter of Daniel and Julia Arwine.

Arwine Cemetery remains active.

Arwine Cemetery remains active.

Ayres Cemetery

Near the intersection of Beach Street and Interstate 30, what remains of Ayres Cemetery fits in the shade of a live oak tree. It is an island in a sea of asphalt, surrounded by the parking lot of a motel complex.

Near the intersection of Beach Street and Interstate 30, what remains of Ayres Cemetery fits in the shade of a live oak tree. It is an island in a sea of asphalt, surrounded by the parking lot of a motel complex.

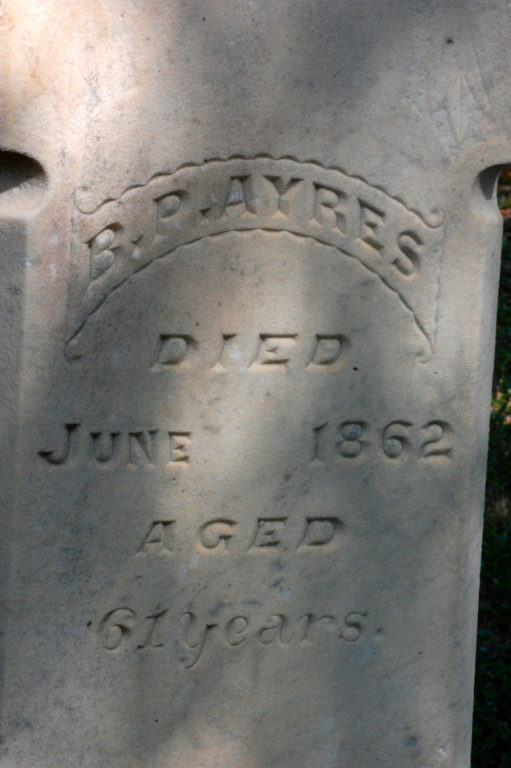

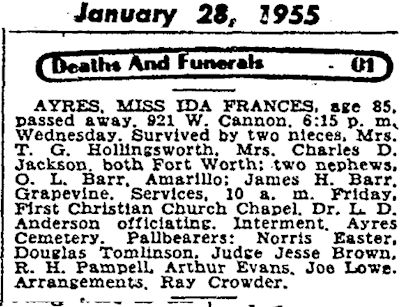

In 1861 Benjamin Patton Ayres (c. 1801-1862) and his wife Emily (c. 1811-1863) homesteaded 320 acres on a hill overlooking the Trinity River and set aside two acres as a family cemetery. According to historian Julia Kathryn Garrett, Ayres was Tarrant County’s first county clerk (a historical marker at the grave of Archibald Franklin Leonard says Leonard was the first county clerk). Ayres also helped organize Fort Worth’s First Christian Church. He was the first person buried in the cemetery. An unknown number of other graves have been obliterated outside the tiny fenced family plot. None of their headstones has survived. Among the early settlers buried there are victims of frontier disease and flooding of the Trinity River. A mile to the east, Ayers Avenue probably is named for the Ayres family.

In 1861 Benjamin Patton Ayres (c. 1801-1862) and his wife Emily (c. 1811-1863) homesteaded 320 acres on a hill overlooking the Trinity River and set aside two acres as a family cemetery. According to historian Julia Kathryn Garrett, Ayres was Tarrant County’s first county clerk (a historical marker at the grave of Archibald Franklin Leonard says Leonard was the first county clerk). Ayres also helped organize Fort Worth’s First Christian Church. He was the first person buried in the cemetery. An unknown number of other graves have been obliterated outside the tiny fenced family plot. None of their headstones has survived. Among the early settlers buried there are victims of frontier disease and flooding of the Trinity River. A mile to the east, Ayers Avenue probably is named for the Ayres family.

Ida Ayres was the last person buried in the cemetery.

Ida Ayres was the last person buried in the cemetery.

Henderson Cemetery

Even if someone told you that little Henderson Cemetery is on Village Creek Road just north of Martin Luther King Jr. Freeway, you might have a hard time finding it. It’s tiny, and it’s hidden by a screen of trees two hundred feet off the road. Forty years ago the cemetery was on one of the farms of the Henderson family.

Even if someone told you that little Henderson Cemetery is on Village Creek Road just north of Martin Luther King Jr. Freeway, you might have a hard time finding it. It’s tiny, and it’s hidden by a screen of trees two hundred feet off the road. Forty years ago the cemetery was on one of the farms of the Henderson family.

In 1895 there were four Henderson homesteads in the area. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

In 1895 there were four Henderson homesteads in the area. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

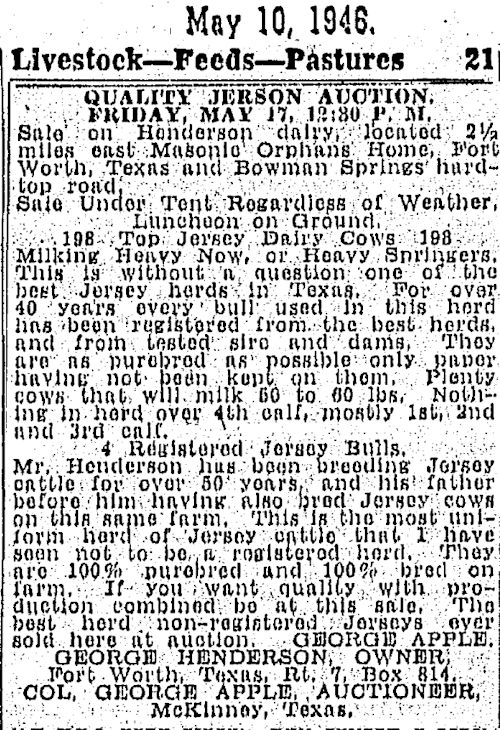

George Henderson’s dairy was 2.5 miles east of the Masonic Home on Bowman Springs Road. Henderson Cemetery is 2.1 miles east of the home (and .5 mile northeast of Parker Henderson Road).

George Henderson’s dairy was 2.5 miles east of the Masonic Home on Bowman Springs Road. Henderson Cemetery is 2.1 miles east of the home (and .5 mile northeast of Parker Henderson Road).

The cemetery contains only eleven graves. The oldest marked grave is that of Fannie Evans (1817-1867). Amanda and Robert Henderson were born in 1820 and married in 1846.

The cemetery contains only eleven graves. The oldest marked grave is that of Fannie Evans (1817-1867). Amanda and Robert Henderson were born in 1820 and married in 1846.

Harrison Cemetery

Like Henderson Cemetery, one-acre Harrison Cemetery on Meadowbrook Drive north of Ederville Road (see Part 1) in far east Fort Worth is hidden from street view and doesn’t get a lot of TLC. The cemetery was established for the family of early settler D. C. Harrison. The earliest grave is that of Mary Harrison (1864-1871). The Harrisons intermarried with the family of mill owner R. A. Randol, who bought the property, protected the cemetery with a deed restriction, and buried his brother John there after John was killed in an accident at the mill in 1894.

Like Henderson Cemetery, one-acre Harrison Cemetery on Meadowbrook Drive north of Ederville Road (see Part 1) in far east Fort Worth is hidden from street view and doesn’t get a lot of TLC. The cemetery was established for the family of early settler D. C. Harrison. The earliest grave is that of Mary Harrison (1864-1871). The Harrisons intermarried with the family of mill owner R. A. Randol, who bought the property, protected the cemetery with a deed restriction, and buried his brother John there after John was killed in an accident at the mill in 1894.

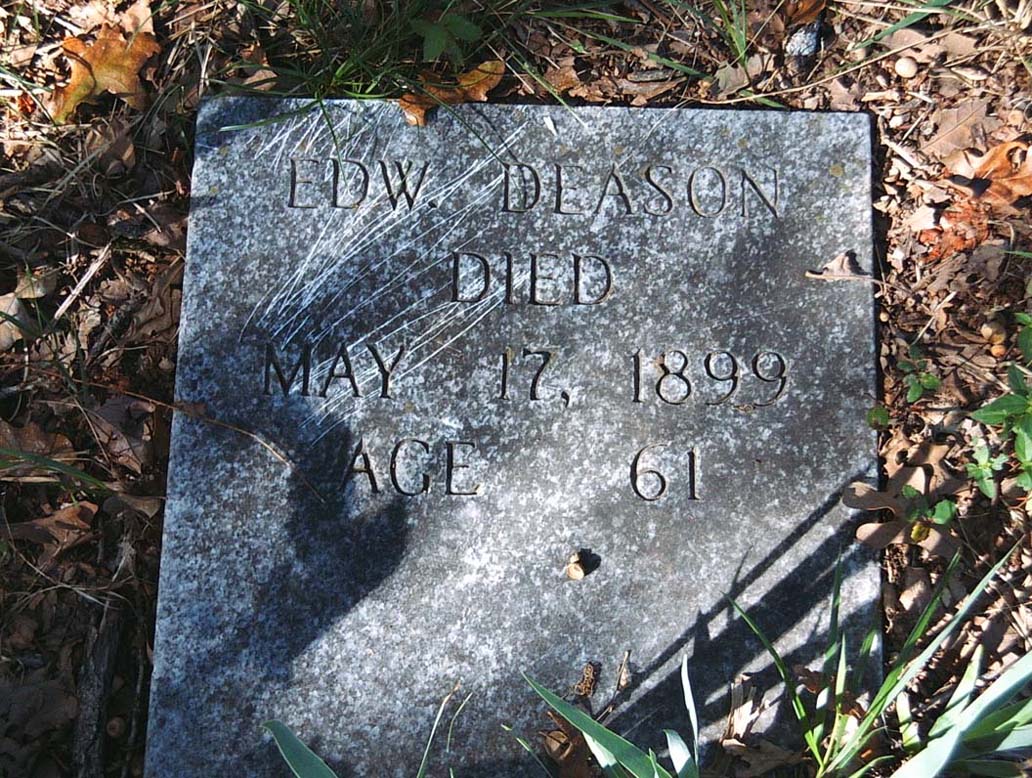

Edward Deason was born in Alabama and came to Texas in 1878. He is one of about sixty persons buried in Harrison Cemetery. Many of the graves are not marked.

Edward Deason was born in Alabama and came to Texas in 1878. He is one of about sixty persons buried in Harrison Cemetery. Many of the graves are not marked.

Mitchell Cemetery

Just northeast of the stockyards, Mitchell Cemetery lies between two active railroad tracks in a strip of railroad right-of-way 150 feet wide. The cemetery is south of Northeast 28th Street and west of Decatur Avenue.

Just northeast of the stockyards, Mitchell Cemetery lies between two active railroad tracks in a strip of railroad right-of-way 150 feet wide. The cemetery is south of Northeast 28th Street and west of Decatur Avenue.

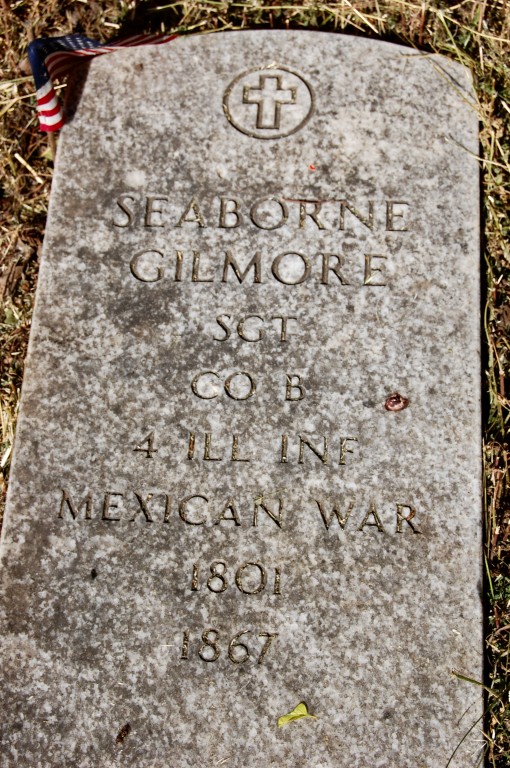

Only one legible original tombstone remains: that of Seaborne Gilmore, who in 1850 was elected Tarrant’s first county judge. Gilmore was father-in-law of Tarrant County Sheriff John B. York, who in 1861 was killed in a confrontation with Archibald Young Fowler.

Only one legible original tombstone remains: that of Seaborne Gilmore, who in 1850 was elected Tarrant’s first county judge. Gilmore was father-in-law of Tarrant County Sheriff John B. York, who in 1861 was killed in a confrontation with Archibald Young Fowler.

Parker Cemetery

Just north of Highway 10 in Hurst is Parker Cemetery.

Just north of Highway 10 in Hurst is Parker Cemetery.

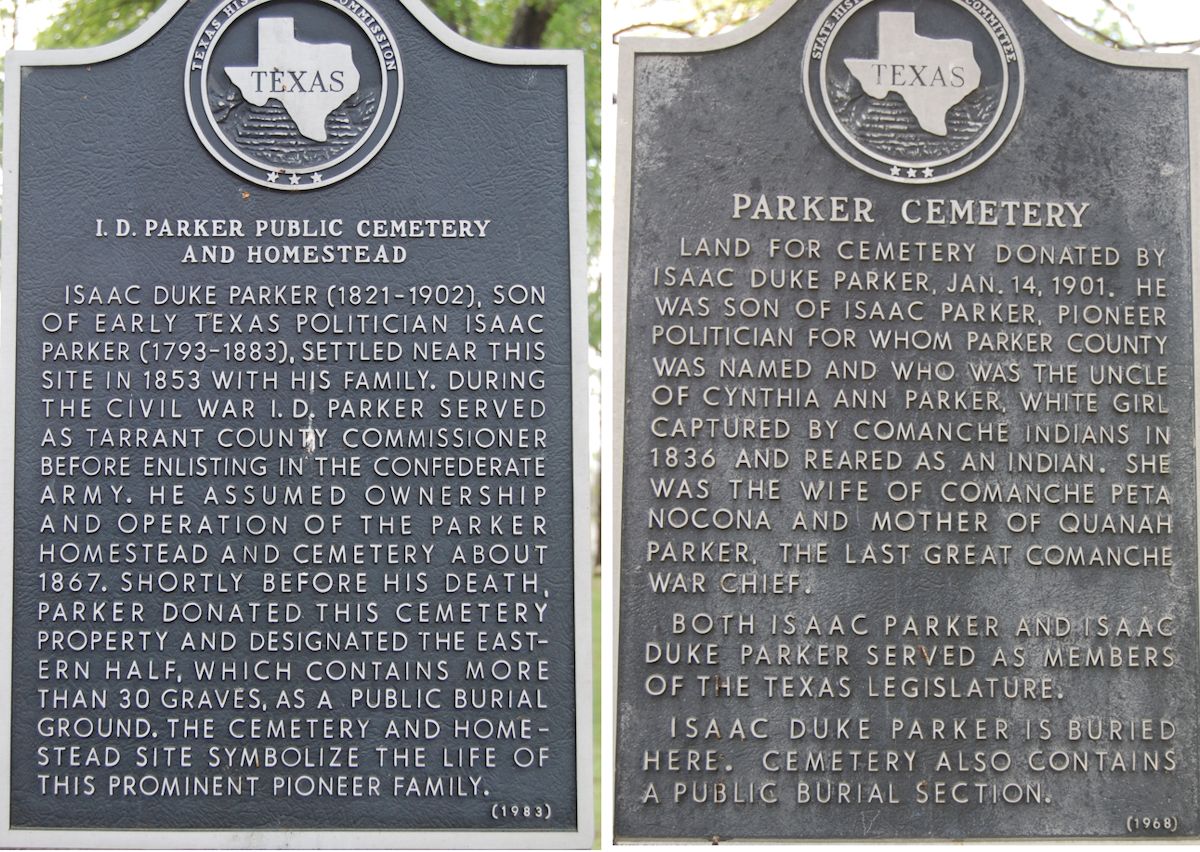

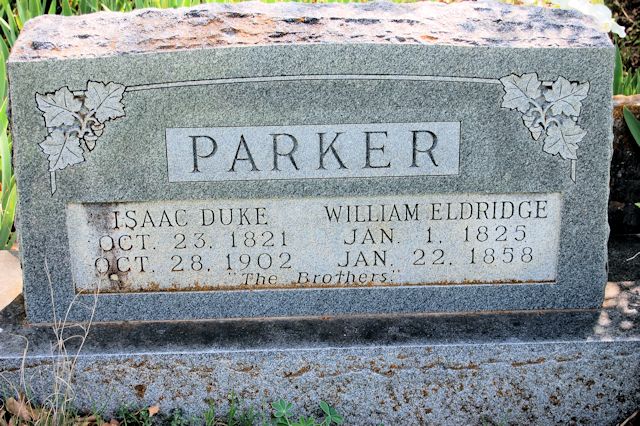

The cemetery consists of a fenced Parker family section and an unfenced public section. The donor in 1901 was Isaac Duke Parker, son of Isaac Parker, a remarkable Texas pioneer whose cabin is on display at Log Cabin Village. The homestead had passed from father to son. The elder Parker is buried in the county named for him.

The cemetery consists of a fenced Parker family section and an unfenced public section. The donor in 1901 was Isaac Duke Parker, son of Isaac Parker, a remarkable Texas pioneer whose cabin is on display at Log Cabin Village. The homestead had passed from father to son. The elder Parker is buried in the county named for him.

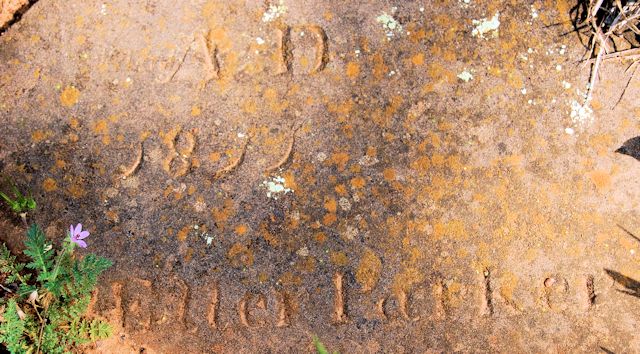

Some of the tombstones are made of sandstone, which is prone to erode and break. Some of the graves in the public section date to the 1850s and are marked with only fieldstones.

Some of the tombstones are made of sandstone, which is prone to erode and break. Some of the graves in the public section date to the 1850s and are marked with only fieldstones.

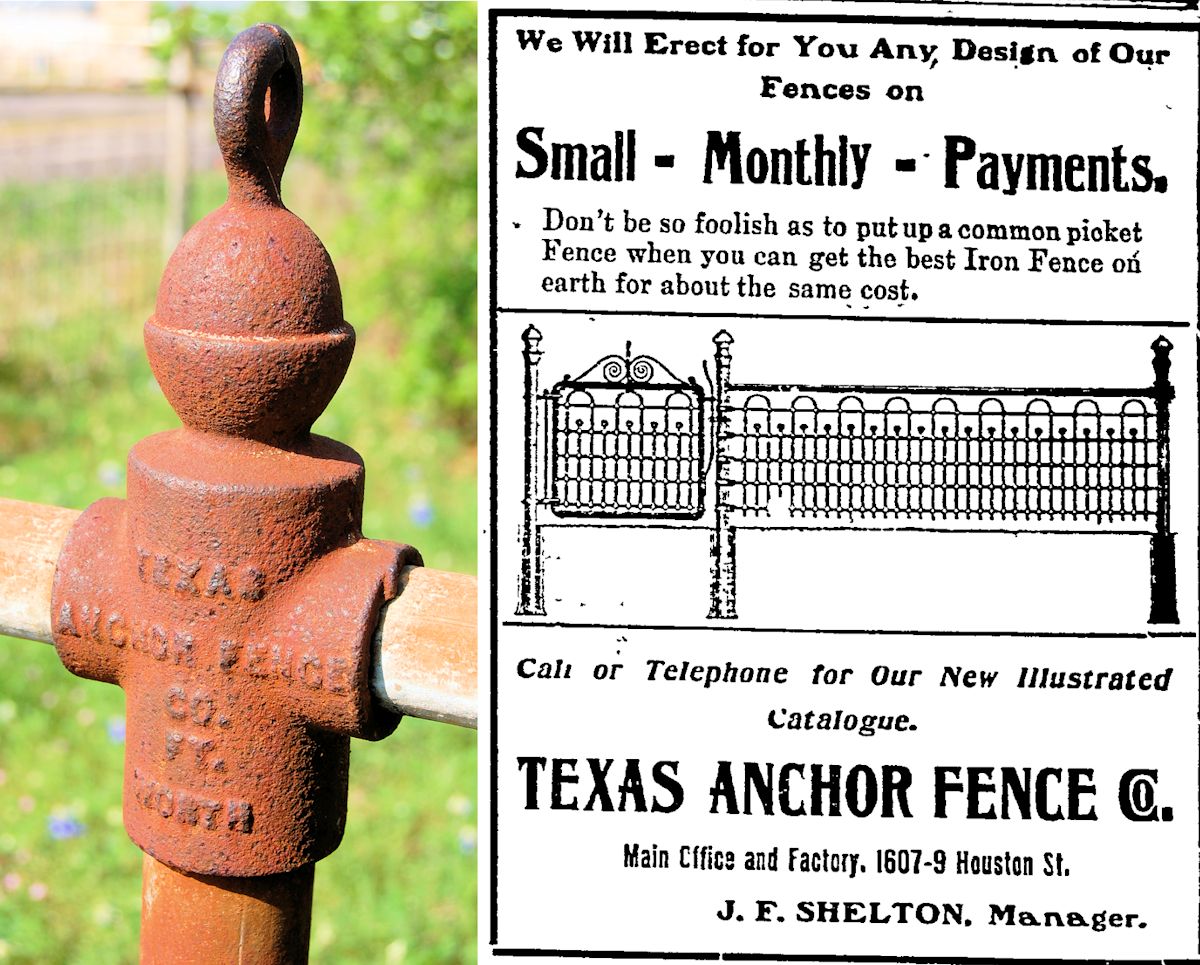

The cemetery fence was made by Texas Anchor and Fence Company, founded in 1901. Fort Worth Register ad is from 1902.

The cemetery fence was made by Texas Anchor and Fence Company, founded in 1901. Fort Worth Register ad is from 1902.

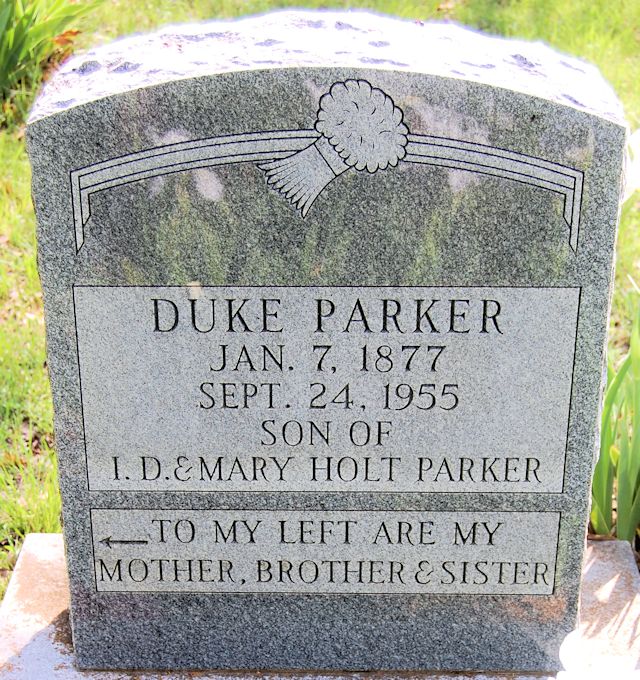

“Isaac” and “Duke” were common names for Parker men. This is the elder Isaac Parker’s grandson.

“Isaac” and “Duke” were common names for Parker men. This is the elder Isaac Parker’s grandson.

Although family patriarch Isaac Parker is buried in Parker County, his first wife, Lucy, is buried in the Hurst family plot.

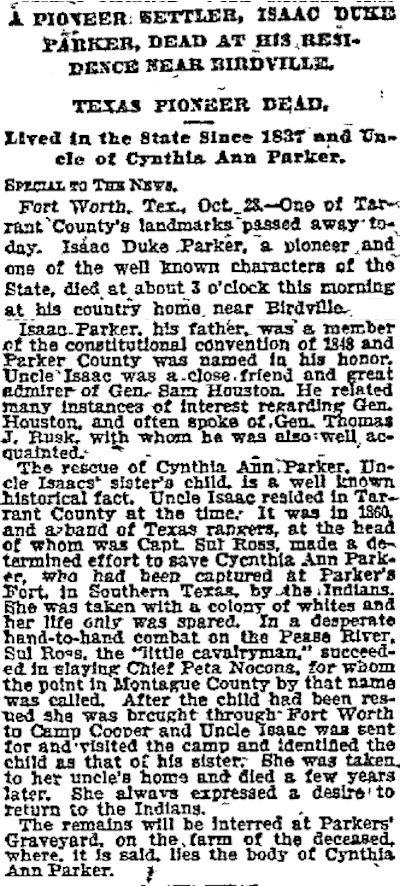

The “it is said” in this clip from the October 29, 1902 Dallas Morning News about Cynthia Ann Parker is in error. She lived at the Parker farm after her “repatriation,” but she died and was buried in Anderson County and later reburied with son Quanah Parker at Fort Sill.

The “it is said” in this clip from the October 29, 1902 Dallas Morning News about Cynthia Ann Parker is in error. She lived at the Parker farm after her “repatriation,” but she died and was buried in Anderson County and later reburied with son Quanah Parker at Fort Sill.

Islands of Eternity (Part 3): Family First (West Side)

Posts About Cemeteries

While reading the news clip, I kept hearing it in the voice used by Dustin Hoffman to narrate Little Big Man. I think I need some sleep.

I recently watched The Graduate and Wag the Dog, so I can’t “hear” his Little Big Man voice now.