Quality Hill (see Part 1) was Fort Worth’s most affluent neighborhood early in the twentieth century, but some unpleasant facts of life even money and influence can’t change.

For example:

1. The city workhouse, temporary home of prisoners who worked off their fines a dollar a day, was located just six hundred feet west of Quality’s Hill’s Penn Street.

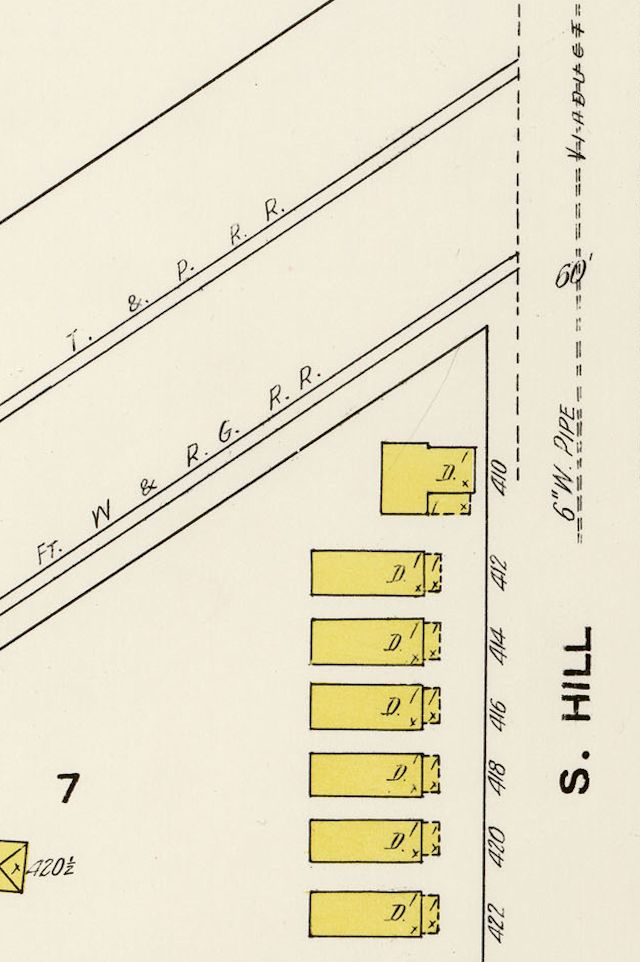

2. Summit Avenue, the showcase street of elegant Quality Hill, was split into north and south sections by a most inelegant intrusion: the tracks of the Texas & Pacific and Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroads. A viaduct carried the street over the tracks. The steam-driven trains were loud, smelly, and smoky. Hardly conducive to the ambience of affluence. In real estate terms, the location, location, location of that narrow strip through Quality Hill was so bad, bad, bad that the “have”s of the Hill did not want it. That left the “have-not”s free to occupy it.

And so they did.

Hunkering in the shadow of the viaduct on the west side of the 400 block of South Summit Avenue (still called “Hill Street” on this 1910 map) were seven small wooden houses—six of them shotgun houses.

Hunkering in the shadow of the viaduct on the west side of the 400 block of South Summit Avenue (still called “Hill Street” on this 1910 map) were seven small wooden houses—six of them shotgun houses.

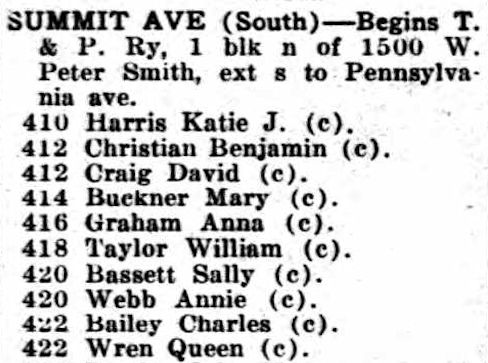

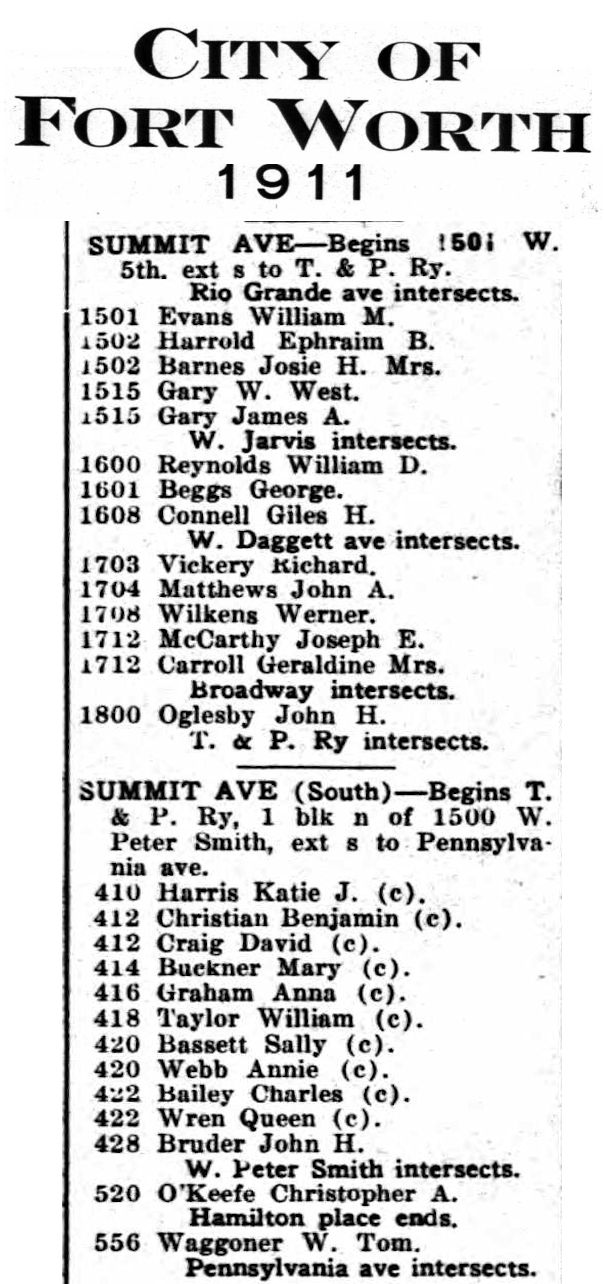

The 1911 city directory lists the occupants of the seven houses. Fort Worth city directories identified African Americans by race (a “c” for “colored”) into the 1920s.

The 1911 city directory lists the occupants of the seven houses. Fort Worth city directories identified African Americans by race (a “c” for “colored”) into the 1920s.

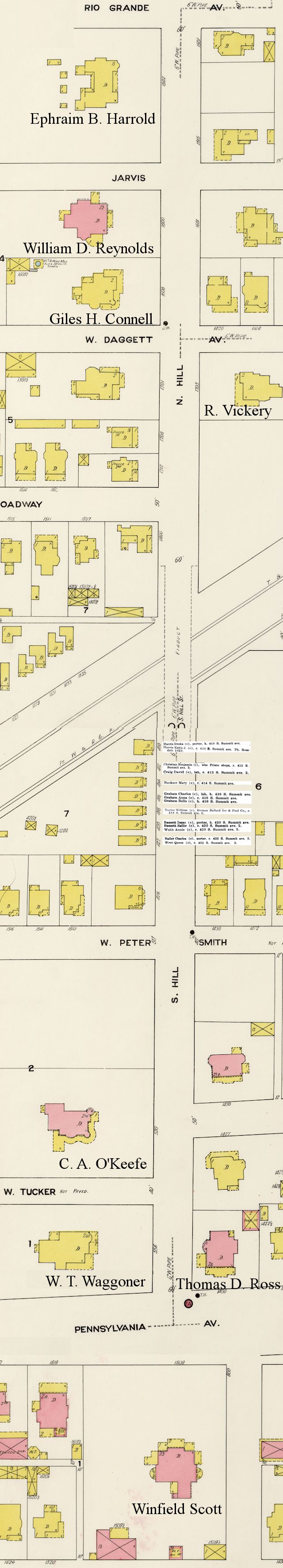

The African-American residents of the shotgun houses of Quality Hill lived with white millionaires to the north and south of them. Five hundred feet to the north, for example, was the fine home of Richard L. Vickery, who developed Glenwood and for whom the boulevard is named. Five hundred feet to the south was the mansion of cattleman Christopher Augustus O’Keefe, who also built the Blackstone Hotel.

The African-American residents of the shotgun houses of Quality Hill lived with white millionaires to the north and south of them. Five hundred feet to the north, for example, was the fine home of Richard L. Vickery, who developed Glenwood and for whom the boulevard is named. Five hundred feet to the south was the mansion of cattleman Christopher Augustus O’Keefe, who also built the Blackstone Hotel.

The 1910 map above shows that the small, rectangular shotgun houses on their tiny lots stood in sharp contrast to the large, multi-storied, multi-angled mansions of Quality Hill with their curved porches and bay windows on large, landscaped lots.

Because the viaduct was the connector between the north and south sections of Quality Hill and between Quality Hill and downtown, as the “have”s crossed the viaduct in their buggies and later in their chauffeur-driven automobiles, they passed a few feet beside (and a few feet above) the shotgun houses of the “have-not”s. Perhaps the “have-not”s, as they sat on their front porches, looked up and saw the fine automobiles of the “have”s pass by. Perhaps the “have”s in their automobiles looked down and saw the “have-not”s on their front porches, shelling peas, mending clothes, or fanning themselves in the summer heat.

The “have-not”s, for their part, living at ground level beside the elevated viaduct, probably traveled north on foot across the railroad tracks.

The 1911 city directory lists occupations only for the male occupants of the shotgun houses: three porters, two laborers, a railroad worker, and a fireman for an ice and fuel company. No occupation is listed for the women, but see 1910 census below.

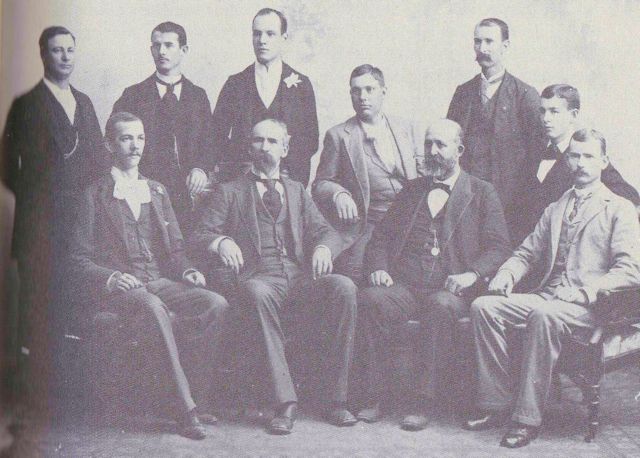

Elsewhere to the north and south of the shotgun houses of Quality Hill as shown on the map above, Ephraim B. Harrold was a banker and cattleman. This photo of the 1890s shows officers of First National Bank. Second from the left on the front row is bank president Martin B. Loyd. To his right is Harrold.

Elsewhere to the north and south of the shotgun houses of Quality Hill as shown on the map above, Ephraim B. Harrold was a banker and cattleman. This photo of the 1890s shows officers of First National Bank. Second from the left on the front row is bank president Martin B. Loyd. To his right is Harrold.

William D. Reynolds was a cattleman.

Giles H. Connell was a director of First National Bank.

W. T. Waggoner made his millions in oil and cattle.

Thomas D. Ross was an attorney.

Winfield Scott was a capitalist, Fort Worth’s biggest taxpayer. He and Harrold built the Scott-Harrold Building on 5th Street downtown next to the Kress Building.

The 1911 city directory lists all the occupants—“have”s and “have-not”s—of Summit Avenue from Rio Grande Avenue south to its end at Thistle Hill on Pennsylvania Avenue.

The 1911 city directory lists all the occupants—“have”s and “have-not”s—of Summit Avenue from Rio Grande Avenue south to its end at Thistle Hill on Pennsylvania Avenue.

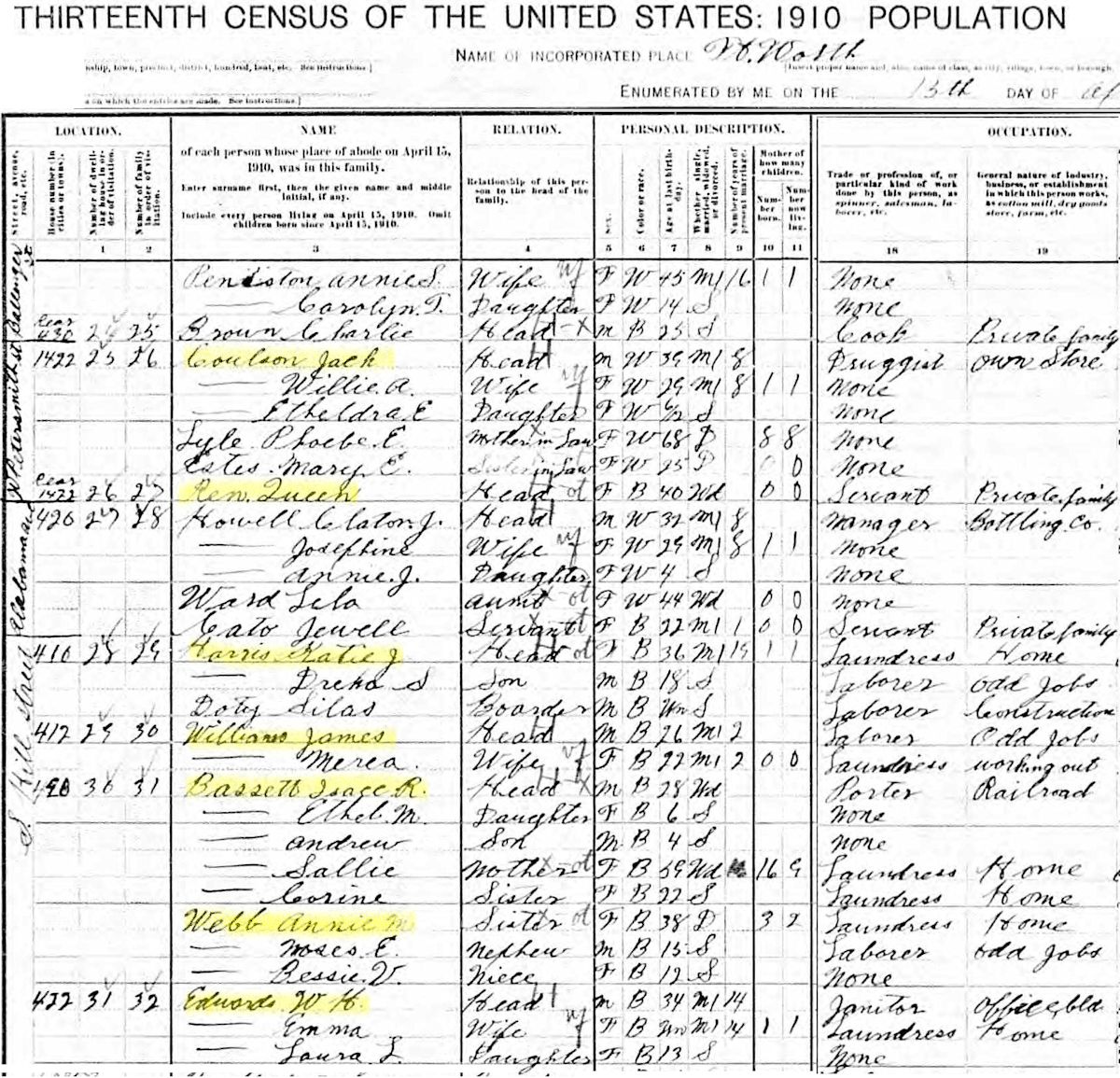

The 1910 census lists occupants of four of the shotgun houses. All occupants were renters. Possibly all the houses were owned by the same landlord. Occupations of the tenants were laundress (at home), laborer (odd jobs, construction), porter (railroad), and janitor (office building). At least one “have-not” of Quality Hill worked for a “have” of Quality Hill: In the 1910 census Queen Wren was a servant of the Jack Coulsons and lived in quarters in the rear of their lot at 1422 West Peter Smith Street, two houses off South Summit Avenue. By 1911 Wren had moved across the viaduct to the shotgun house at 422 South Summit.

The 1910 census lists occupants of four of the shotgun houses. All occupants were renters. Possibly all the houses were owned by the same landlord. Occupations of the tenants were laundress (at home), laborer (odd jobs, construction), porter (railroad), and janitor (office building). At least one “have-not” of Quality Hill worked for a “have” of Quality Hill: In the 1910 census Queen Wren was a servant of the Jack Coulsons and lived in quarters in the rear of their lot at 1422 West Peter Smith Street, two houses off South Summit Avenue. By 1911 Wren had moved across the viaduct to the shotgun house at 422 South Summit.

Jack Coulson owned a drugstore downtown. His wife was often mentioned in the society pages of the newspaper.

Jack Coulson owned a drugstore downtown. His wife was often mentioned in the society pages of the newspaper.

Fast-forward to 1952. The cheaply built shotgun houses of Quality Hill were at least forty-two years old. But this aerial photo shows the shotgun houses (labeled S) still standing, forgotten as they hunkered in the shadow of the Summit Avenue viaduct (V). Also shown are Westchester Plaza (WP), Thistle Hill (TH), and Pennsylvania Avenue Hospital (PAH).

Fast-forward to 1952. The cheaply built shotgun houses of Quality Hill were at least forty-two years old. But this aerial photo shows the shotgun houses (labeled S) still standing, forgotten as they hunkered in the shadow of the Summit Avenue viaduct (V). Also shown are Westchester Plaza (WP), Thistle Hill (TH), and Pennsylvania Avenue Hospital (PAH).

But by 1963 the shotgun houses were gone. But so were most of the mansions. Progress was the great equalizer of the “have”s and the “have-not”s of Quality Hill.

Great history lesson! I was born and raised in Fort Worth. As was my dad. My mom was born in Hamilton. I was also a member of FW women’s club. It is beautiful inside.

Wow, those duds had some money. I’m living in the wrong times. Great read. Love TH??