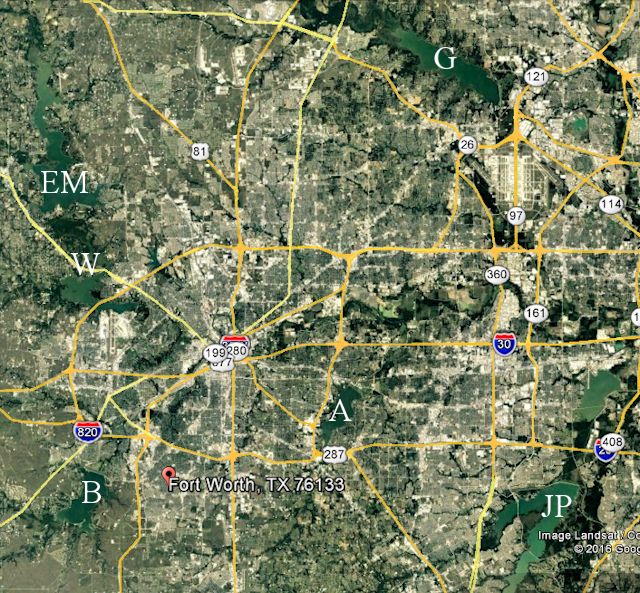

Summer is lake season, and Fort Worth is surrounded by six big ones. They are separated in time by as much as seventy-two years. They are separated in space by as much as thirty-two miles. Most of us have fond memories of our six big lakes because they are where we have attended family, school, church, and other group outings, where we have picnicked and fished and swum and boated and courted. But these lakes didn’t just magically materialize so that you and I would have a place to catch crappie, water ski, and watch the submarine races.

Cowtown Was Looking for “Just Right”

What is the history of our six big lakes (Worth, Eagle Mountain, Benbrook, Grapevine, Arlington, and Joe Pool)?

To begin with, none of our big six was made by nature. Like most lakes, our big six were made by we, the people. And we made them to serve one purpose: to control water in nature. But Fort Worth, like every city, wants to control water in nature in two very different ways: to harness water to use as a resource but also to harness water to prevent floods. Thus, a city has a Goldilocks attitude toward water: A city wants the amount of water that is “just right.” For example, it wants its residents to get enough water to take a bath but not so much water that their house floats down the street.

To begin with, none of our big six was made by nature. Like most lakes, our big six were made by we, the people. And we made them to serve one purpose: to control water in nature. But Fort Worth, like every city, wants to control water in nature in two very different ways: to harness water to use as a resource but also to harness water to prevent floods. Thus, a city has a Goldilocks attitude toward water: A city wants the amount of water that is “just right.” For example, it wants its residents to get enough water to take a bath but not so much water that their house floats down the street.

Because soldiers, like real estate agents, know the truth of the axiom “location, location, location,” Fort Worth was doubly blessed from the git-go thanks to Major Ripley Arnold: Fort Worth’s location would have pleased Goldilocks: It was “just right.” It had a source of water—the two forks of the Trinity River—but had no need for flood control because the fort and later the city were located high and dry on the bluff far above the reach of the Trinity River.

(The fort and early city also drew water from wells, such as Frenchman’s Well, from the Cold Springs, and from rainfall stored in cisterns.)

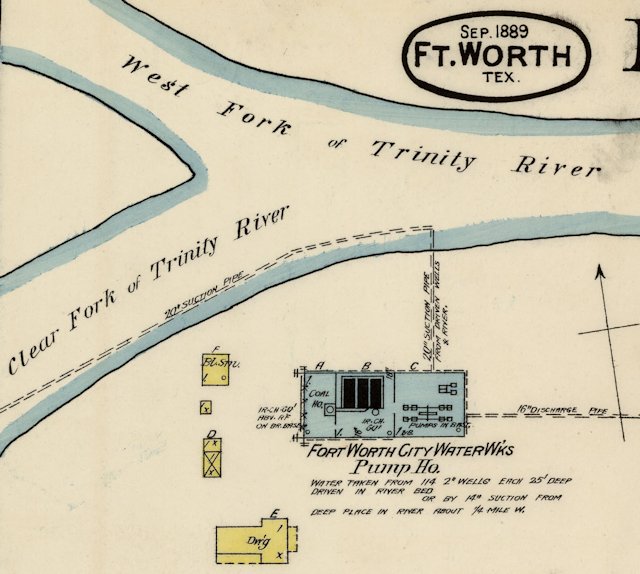

But as the city increased in population, its need for water increased. In 1882 the city built a waterworks and a modest network of fire plugs, mains, and pipes to homes and businesses. The waterworks was located at the confluence of the Clear and West forks and pumped water from both the river and from wells drilled in the river channel. The minimum charge for water to a four-room house was five dollars a year.

But as the city increased in population, its need for water increased. In 1882 the city built a waterworks and a modest network of fire plugs, mains, and pipes to homes and businesses. The waterworks was located at the confluence of the Clear and West forks and pumped water from both the river and from wells drilled in the river channel. The minimum charge for water to a four-room house was five dollars a year.

In 1882 Fort Worth’s area was still confined essentially to today’s downtown on the bluff and still had no need for flood control. But as the city grew in area, it spread beyond the bluff into areas along the river east, west, and north of downtown. With expansion into those low-lying areas Fort Worth did have need for flood control.

Remember: The Trinity River of that time was nothing like the Trinity River of today. The Trinity of that time looked more like Sycamore Creek—narrow, shallow, and placid except after heavy rain upstream in its watershed.

But heavy rain in that considerable watershed above Fort Worth could gorge that narrow, shallow, and placid Trinity River with a thunderous wall of water overnight, as it did in 1889.

During the flood of 1889 the river was two miles wide to the north and east of town. To the west, where Trinity Park is today, the farm of banker and civic leader Khleber Miller Van Zandt was flooded.

After the flood of 1889 Fort Worth began to consider flood control. Engineers said levees could protect the areas north and east of downtown.

But the city was slow to provide flood control. The city was quicker to provide a larger water supply. In 1892 the city drilled a dozen artesian wells and built a new waterworks on the Clear Fork upstream from the 1882 waterworks.

In 1894 civil and hydraulic engineer John B. Hawley recommended that the city buy a tract of land on the Clear Fork southwest of the city and build a large dam to impound water to supply the city. Like the levees, his suggestion was debated but not acted upon, although the city did build a series of dams on the Clear Fork to impound water to augment the city’s artesian wells. These dams were modest and did not form lakes. One dam was located where today’s Lancaster Avenue bridge is.

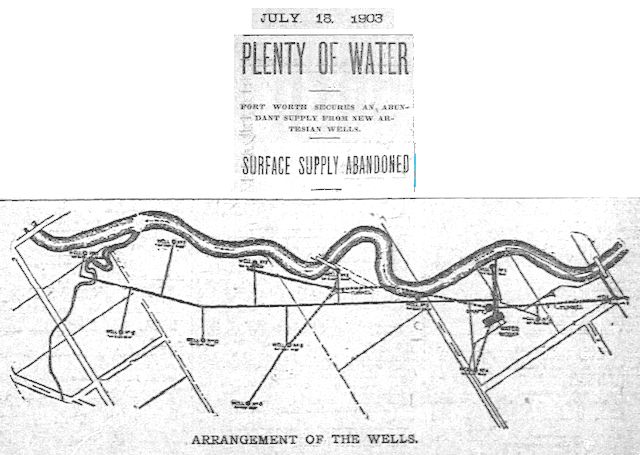

But by 1903 the city had given up on the river as a source of water. Instead the city installed the Meade system, which consisted of pumps and artesian wells located within a radius of sixteen hundred feet of the waterworks. The wells were connected to the waterworks by a network of more than a mile of horizontal tunnels 173 feet deep in the ground.

But by 1903 the city had given up on the river as a source of water. Instead the city installed the Meade system, which consisted of pumps and artesian wells located within a radius of sixteen hundred feet of the waterworks. The wells were connected to the waterworks by a network of more than a mile of horizontal tunnels 173 feet deep in the ground.

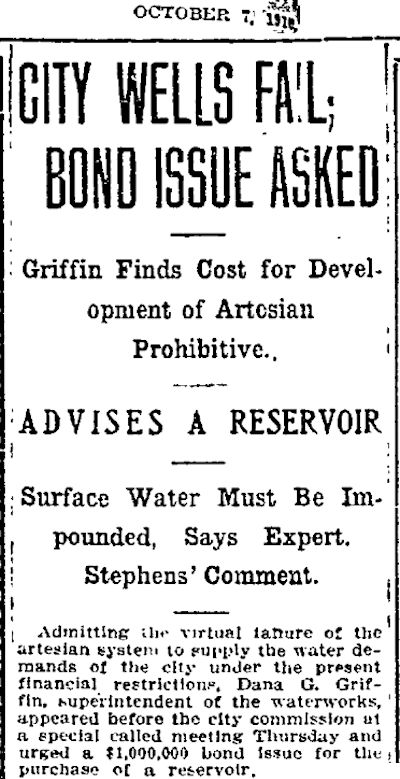

But the wells, like the river, were dependent on rainfall, and the Meade system did not perform to expectations. By 1906 the capacity of the wells had decreased. In 1907 the city again began to consider building a dam and reservoir on the river to impound water. In fact, the city bought one thousand acres on the Clear Fork southwest of Benbrook (selected by civil engineer Charles M. Davis) for that purpose but did not follow through.

Meanwhile the city still had not done much to control flooding of the river.

Then came the flood of 1908. Within days of the flood the city began planning a system of levees to protect the low-lying areas west, east, and north of downtown. (More on the levees later.)

Meanwhile, to augment the increasingly undependable artesian well system, in 1909 the city again turned to the river and began supplying industrial customers with river water pumped from the 1882 waterworks.

Also in 1909 the city annexed the city of North Fort Worth. Suddenly the city had a lot more people and a lot more area—an area prone to flooding by the Trinity River and Marine Creek.

By 1910 the city finally was determined to control the Trinity River in both ways: harness it to provide a larger water supply and harness it to prevent flooding. (The memory of the South Side fire of 1909, which had strained the city’s water supply as firemen fought the fire, was another incentive for a larger water supply.)

In 1910 the city commission created a board of waterworks supply engineers. That board recommended a “reservoir to collect and conserve . . . flood waters.”

As the city’s artesian wells continued to sputter, the superintendent of the waterworks also recommended a reservoir.

As the city’s artesian wells continued to sputter, the superintendent of the waterworks also recommended a reservoir.

In 1911 the board recommended a site on the West Fork. That year the city bought five thousand acres of mostly undeveloped land on the West Fork six miles northwest of town. Owners were offered what the city felt was a fair price—an average of $35 an acre ($900 today). If a seller refused the offer, the city filed a condemnation suit, and the seller was paid an amount determined by a board of appraisers.

First of the Big Six: Lake Worth

In July 1911 the city advertised for bids to build the reservoir. It was a small ad with big numbers: 300,000 cubic yards of earthen embankment, 60,000 cubic yards of concrete for the spillway, a pipeline forty inches in diameter and six and a half miles long from the reservoir to the waterworks in town.

In July 1911 the city advertised for bids to build the reservoir. It was a small ad with big numbers: 300,000 cubic yards of earthen embankment, 60,000 cubic yards of concrete for the spillway, a pipeline forty inches in diameter and six and a half miles long from the reservoir to the waterworks in town.

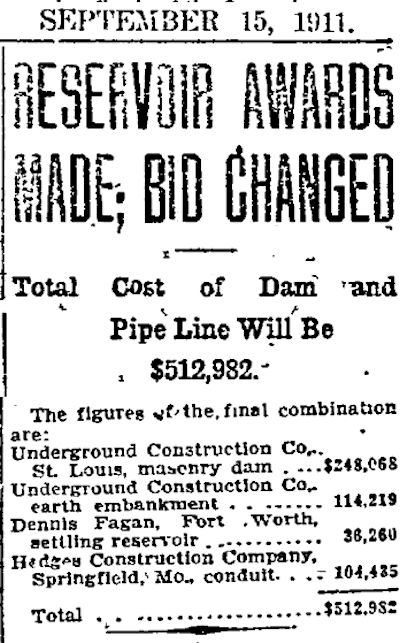

In September the city awarded contracts totaling $512,982 ($13.4 million today) to construct the dam, a settling basin, and the pipeline.

In September the city awarded contracts totaling $512,982 ($13.4 million today) to construct the dam, a settling basin, and the pipeline.

In addition, C. T. Hodge was awarded the contract to clear the timber from the reservoir site and was allowed to keep the timber he cut. He sold it as cordwood through a classified ad in the Star-Telegram.

Construction of the reservoir and dam of Lake Worth began on September 25, 1911. The dam and reservoir were a gargantuan civil engineering project. Three hundred workers lived in “sanitary camps” at the reservoir site. Teams of horses or mules and a fleet of “motor trucks” excavated, hauled, graded, and rolled tons of earth and concrete.

Construction of the reservoir and dam of Lake Worth began on September 25, 1911. The dam and reservoir were a gargantuan civil engineering project. Three hundred workers lived in “sanitary camps” at the reservoir site. Teams of horses or mules and a fleet of “motor trucks” excavated, hauled, graded, and rolled tons of earth and concrete.

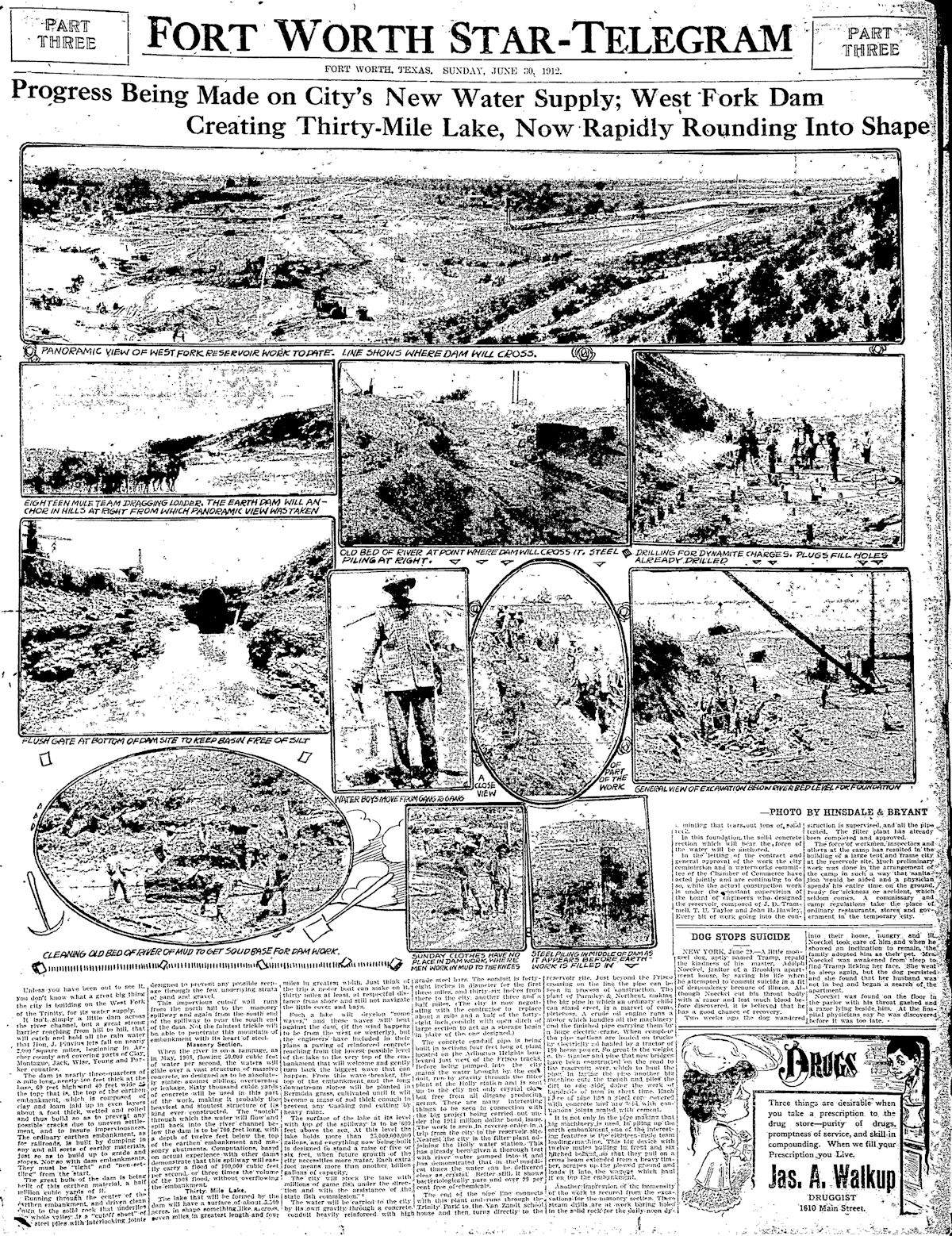

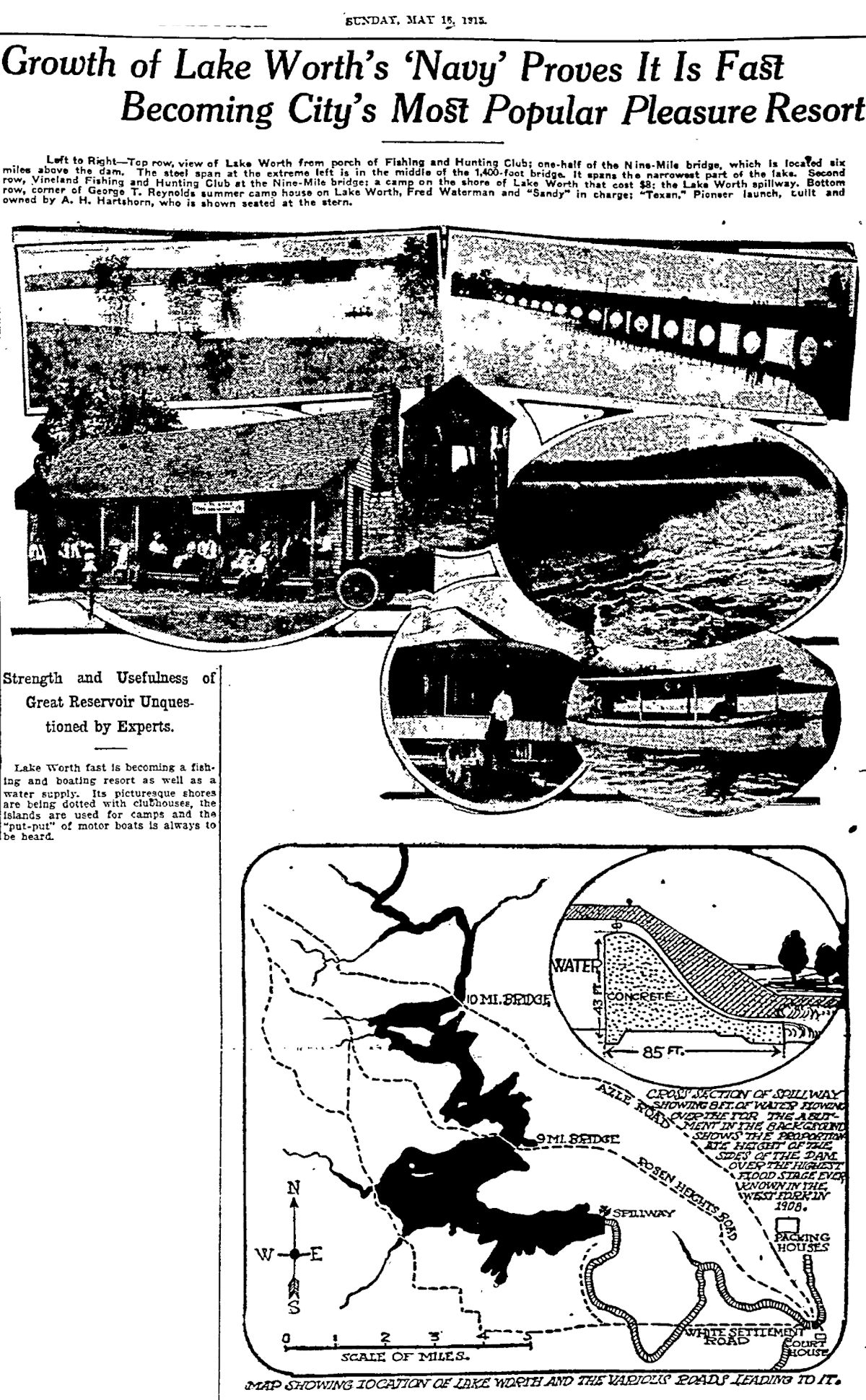

In June 1912 the Star-Telegram published a progress report on the project, pointing out that the dam was three-quarters of a mile long, five hundred feet thick at the base, and sixty feet tall. The reservoir would impound rainfall runoff from seven counties above it and have a capacity of 25 billion gallons of water.

In June 1912 the Star-Telegram published a progress report on the project, pointing out that the dam was three-quarters of a mile long, five hundred feet thick at the base, and sixty feet tall. The reservoir would impound rainfall runoff from seven counties above it and have a capacity of 25 billion gallons of water.

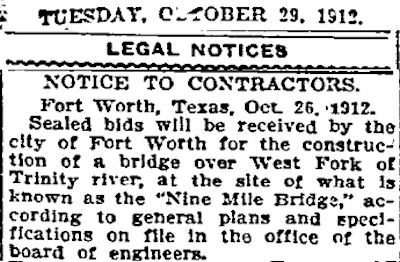

Damming the river created the necessity for one more project: a new Nine Mile Bridge. The old bridge would be too short to span the lake, even though the bridge would be located at the narrow waist of the lake. The new bridge, with wood flooring on concrete piers, would be fourteen hundred feet long. The bridge on Jacksboro Highway would not open until 1929.

Damming the river created the necessity for one more project: a new Nine Mile Bridge. The old bridge would be too short to span the lake, even though the bridge would be located at the narrow waist of the lake. The new bridge, with wood flooring on concrete piers, would be fourteen hundred feet long. The bridge on Jacksboro Highway would not open until 1929.

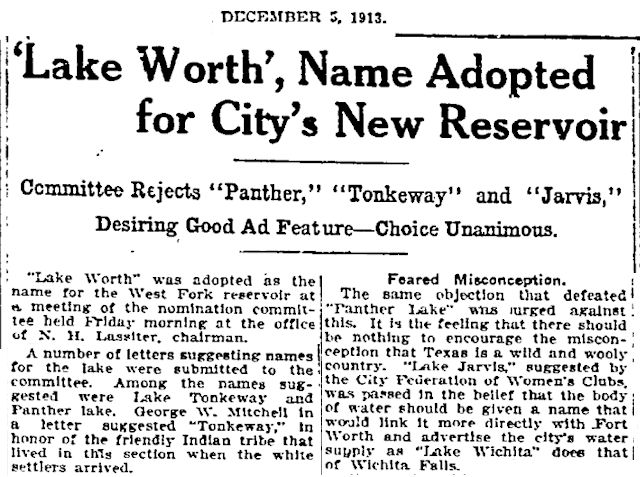

On December 5, 1913 the reservoir, which had been referred to mostly as “the West Fork reservoir,” was given a formal name. Other names considered were Jarvis, Panther, and Tonkeway.

On December 5, 1913 the reservoir, which had been referred to mostly as “the West Fork reservoir,” was given a formal name. Other names considered were Jarvis, Panther, and Tonkeway.

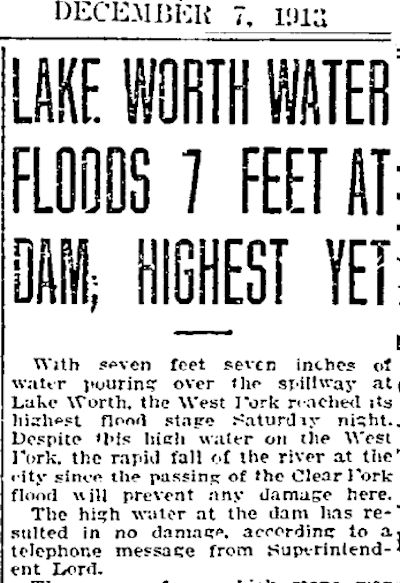

At least twice the Lake Worth project was threatened by the very thing it was being built to contain: heavy rain. One day after the lake was given a name, it was given a test: Heavy rain in the watershed flooded the West Fork, sending water over the Lake Worth spillway more than seven feet high. The dam was not damaged.

At least twice the Lake Worth project was threatened by the very thing it was being built to contain: heavy rain. One day after the lake was given a name, it was given a test: Heavy rain in the watershed flooded the West Fork, sending water over the Lake Worth spillway more than seven feet high. The dam was not damaged.

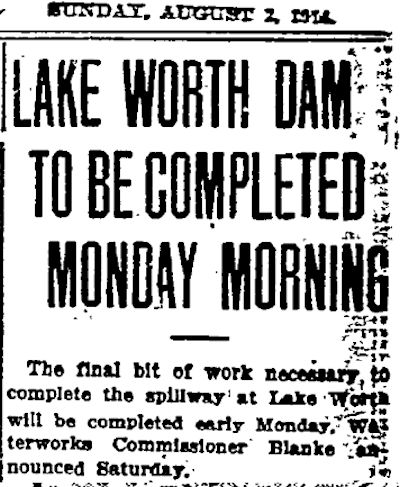

By August 1914 the dam and its spillway were almost completed.

By August 1914 the dam and its spillway were almost completed.

Later that month the Star-Telegram reported that the 4,400-acre lake was filling up as rainfall runoff poured down the river from a watershed of two thousand square miles. Note that the cost of the dam had risen to $1.3 million ($32 million today).

Later that month the Star-Telegram reported that the 4,400-acre lake was filling up as rainfall runoff poured down the river from a watershed of two thousand square miles. Note that the cost of the dam had risen to $1.3 million ($32 million today).

The Trinity River always had a flair for the dramatic. Three days after the lake on the West Fork was reported to be “filling up,” the Star-Telegram wrote that the Clear Fork also was rising. Four hundred families living in the river bottom of the Clear Fork were driven to higher ground. The near West Side was flooded from the confluence southwest to Trinity Park. Streetcar service to Arlington Heights and some railroad service were disrupted.

The Trinity River always had a flair for the dramatic. Three days after the lake on the West Fork was reported to be “filling up,” the Star-Telegram wrote that the Clear Fork also was rising. Four hundred families living in the river bottom of the Clear Fork were driven to higher ground. The near West Side was flooded from the confluence southwest to Trinity Park. Streetcar service to Arlington Heights and some railroad service were disrupted.

On the West Fork, as the river rose the new Lake Worth dam “bore almost the heaviest pressure of water possible” and “held back the bulk of the West Fork’s flood.” The Star-Telegram credited the new lake with minimizing flooding downstream in Fort Worth.

On the West Fork, as the river rose the new Lake Worth dam “bore almost the heaviest pressure of water possible” and “held back the bulk of the West Fork’s flood.” The Star-Telegram credited the new lake with minimizing flooding downstream in Fort Worth.

By August 21 water was running twenty-one inches high over the Lake Worth spillway after “tremendous rains” fell in the West Fork watershed. But “The river was well within its banks at Fort Worth.” Lake Worth was doing what it had been built to do: control the Trinity River.

By August 21 water was running twenty-one inches high over the Lake Worth spillway after “tremendous rains” fell in the West Fork watershed. But “The river was well within its banks at Fort Worth.” Lake Worth was doing what it had been built to do: control the Trinity River.

Lake Worth, three years in the making, was earning its keep. But the project had been beset by problems. There were construction delays, cost overruns. A test of the concrete in the dam found the mix to be weaker than specifications. The city sued contractors. Property owners sued the city. The company building the dam filed for bankruptcy. Workers went on strike. When the concrete conduit from the lake to the city’s waterworks was first tested, it leaked.

The dam was tested by high water again in April 1915. By then also nearing completion was an eleven-mile levee system along the river to protect the low-lying areas to the west, east, and north of downtown. The city had begun planning the levee system days after the flood of 1908. A levee district and board had been created. The levee project had been bedeviled by squabbling—injunctions and lawsuits—between the city and the levee board. But a Star-Telegram editorial in May credited the new lake and the levee system with minimizing flooding in Fort Worth in April 1915.

The dam was tested by high water again in April 1915. By then also nearing completion was an eleven-mile levee system along the river to protect the low-lying areas to the west, east, and north of downtown. The city had begun planning the levee system days after the flood of 1908. A levee district and board had been created. The levee project had been bedeviled by squabbling—injunctions and lawsuits—between the city and the levee board. But a Star-Telegram editorial in May credited the new lake and the levee system with minimizing flooding in Fort Worth in April 1915.

By May 1915 the new lake was so popular with boaters that the Star-Telegram wrote of Lake Worth’s “navy.” Note that Nine Mile Bridge was reached by Rosen Heights Road. Jacksboro Highway did not yet exist.

By May 1915 the new lake was so popular with boaters that the Star-Telegram wrote of Lake Worth’s “navy.” Note that Nine Mile Bridge was reached by Rosen Heights Road. Jacksboro Highway did not yet exist.

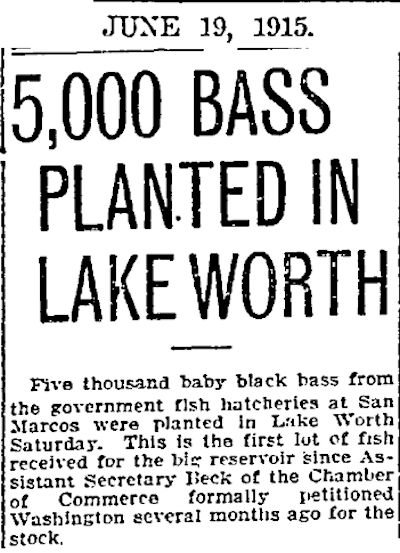

In 1915 five thousand bass were released into the new lake.

In 1915 five thousand bass were released into the new lake.

In 1915 a lot of folks still did not own a car, and there was no mass transit to the new lake. But jitneys—unlicensed taxis—would drive passengers to the lake. Note the “R.” (for “Rosedale”) phone exchange.

In 1915 a lot of folks still did not own a car, and there was no mass transit to the new lake. But jitneys—unlicensed taxis—would drive passengers to the lake. Note the “R.” (for “Rosedale”) phone exchange.

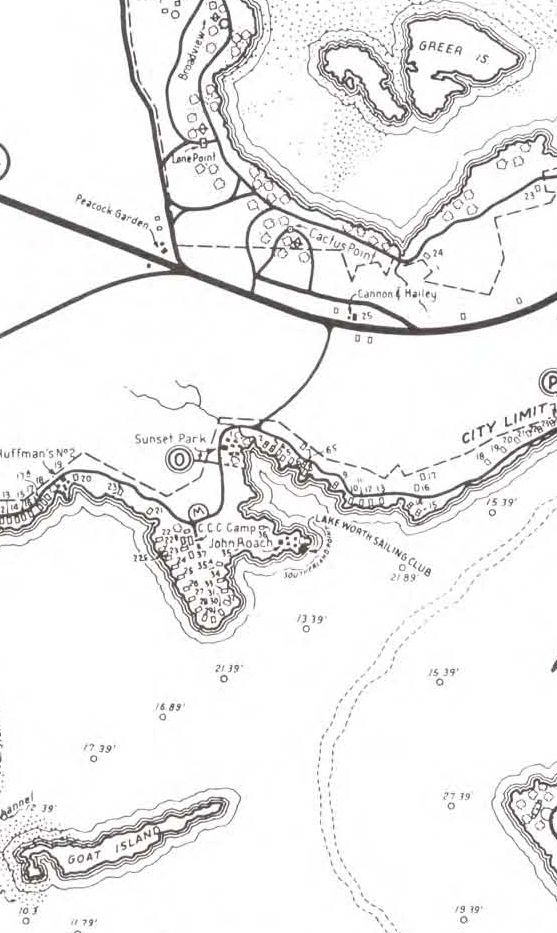

And in 1915 Lake Worth got its first flock of an animal that would become part of lake lore. The Star-Telegram announced that goats would be placed on Crescent Island to do some landscaping.

And in 1915 Lake Worth got its first flock of an animal that would become part of lake lore. The Star-Telegram announced that goats would be placed on Crescent Island to do some landscaping.

In fact, Crescent Island was soon renamed “Goat Island.” Less than two miles to the north in the city’s Broadview Park on the lake in 1958 Reverend Henry Cooper established the New Liberty Mission Rehabilitation Center. The rehabilitation center was known informally as the “Goat Farm” because its residents raised goats for consumption by animals at the Fort Worth Zoo. Just east of the Goat Farm, of course, was Greer Island, home of Lake Worth’s best-known resident.

In fact, Crescent Island was soon renamed “Goat Island.” Less than two miles to the north in the city’s Broadview Park on the lake in 1958 Reverend Henry Cooper established the New Liberty Mission Rehabilitation Center. The rehabilitation center was known informally as the “Goat Farm” because its residents raised goats for consumption by animals at the Fort Worth Zoo. Just east of the Goat Farm, of course, was Greer Island, home of Lake Worth’s best-known resident.

Lake Worth’s dam and reservoir completed and proven, its duty to provide water while preventing floods faded into the background as the perimeter of the lake quickly began to develop: city parks, private campgrounds, beaches, fishing and hunting clubs, taverns and restaurants offering drinks, dinner, and dancing, sailing clubs, boatworks, bait and tackle shops.

Lake Worth’s dam and reservoir completed and proven, its duty to provide water while preventing floods faded into the background as the perimeter of the lake quickly began to develop: city parks, private campgrounds, beaches, fishing and hunting clubs, taverns and restaurants offering drinks, dinner, and dancing, sailing clubs, boatworks, bait and tackle shops.

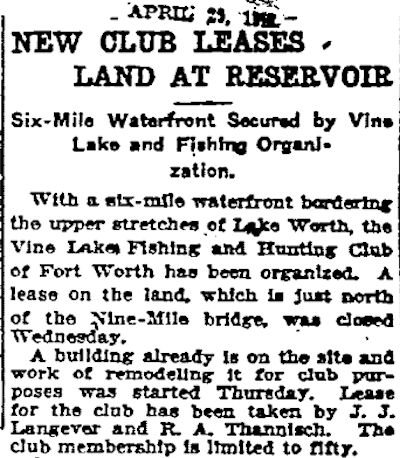

The building may appear to us, a century later, as rather Clampettesque, but one of the first recreational facilities on the new lake was Vine Lake Fishing and Hunting Club, established on land leased by the city to J. J. Langever and Roy A. Thannisch. Roy was a son of Thomas Marion Thannisch, who operated a sixty-five-foot launch, Panther City, on the lake. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The building may appear to us, a century later, as rather Clampettesque, but one of the first recreational facilities on the new lake was Vine Lake Fishing and Hunting Club, established on land leased by the city to J. J. Langever and Roy A. Thannisch. Roy was a son of Thomas Marion Thannisch, who operated a sixty-five-foot launch, Panther City, on the lake. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

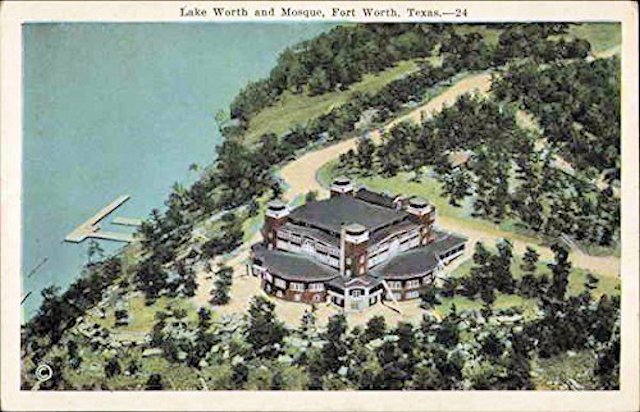

The Shriners built a grand mosque on Reynolds Point in 1917.

The Shriners built a grand mosque on Reynolds Point in 1917.

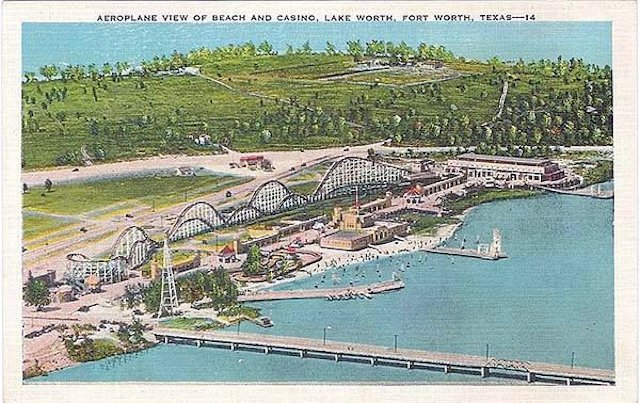

Also that year the city opened at Nine Mile Bridge a municipal bathing beach and bathhouse that would evolve into Casino Beach in 1927.

Also that year the city opened at Nine Mile Bridge a municipal bathing beach and bathhouse that would evolve into Casino Beach in 1927.

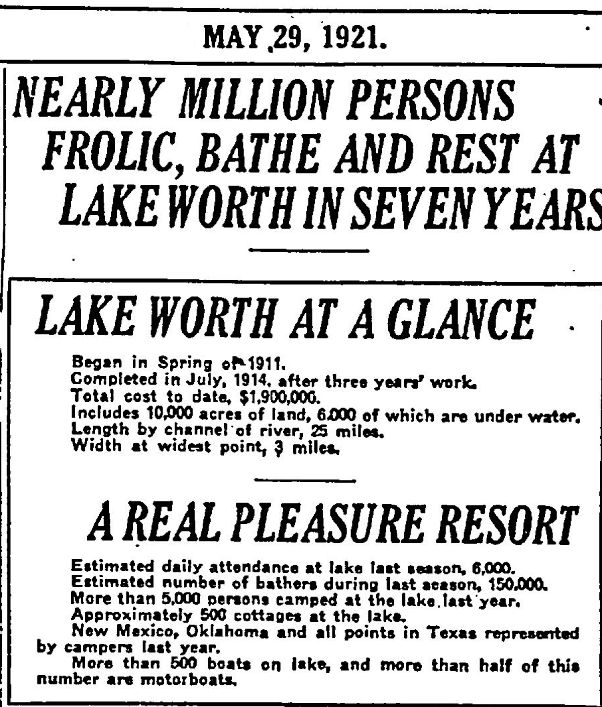

In 1921 the Star-Telegram celebrated the lake’s first seven years by listing its vital statistics.

In 1921 the Star-Telegram celebrated the lake’s first seven years by listing its vital statistics.

Gradually people began to go to Lake Worth not only to play but also to live: In 1923 Amon Carter bought nine hundred acres and developed his Shady Oak Farm at the lake to entertain the rich and powerful.

In 1930 the lake’s surface froze so solidly that people skated, sledded, sailed, and even drove their automobiles on the lake.

By 1949 Indian Oaks, a community on land formerly owned by cattleman George T. Reynolds, had grown enough to incorporate as “Lake Worth Village” (now the city of Lake Worth).

Yes, Lake Worth and the water supply and flood control it provided had been a long time coming, but when many people in Fort Worth looked at their new lake they would echo the sentiment of Goldilocks: “Just right.”

In Search of “Just Right”: Goldilocks and the Six Lakes (Part 2)

Great page! I grew up in Lake Worth and did not know most of what I just read! Fantastic!

Thanks for this informative page. Do you have any information or pictures of the Reporter Publishing Company in Ft. Worth?

I mention it briefly in this post.

I have e-mailed you three newspaper clips.

Great news clips, photos and information!

I love learning new history about the old stomping grounds.

I am currently helping friends remodel the old Holiday Ranch on Jacksboro Highway in Lakeside.

Do you have any old clips or photos concerning Holiday Ranch?

Thanks, Terry. I sent you a few clips.