In April 1922, eight years after Lake Worth (see Part 1), the first of Fort Worth’s big six lakes, began providing both a source of water and flood protection on the West Fork of the Trinity River, Fort Worth was swept by another flood. Twenty-four inches of water poured over the spillway of the Lake Worth dam. The Clear Fork and Sycamore and Marine creeks—which were not dammed—flooded. When water from those four sources swept into Fort Worth a levee broke. The city waterworks and the electric plant, both situated near the river, were flooded, leaving parts of town without drinking water and power. Phone service was out. Interurban service to Dallas and to Cleburne was halted. People were stranded in trees and rooftops. Arlington Heights and the North Side, the Star-Telegram wrote, were “marooned.”

Fort Worth had a face a hard truth: It needed still more flood control.

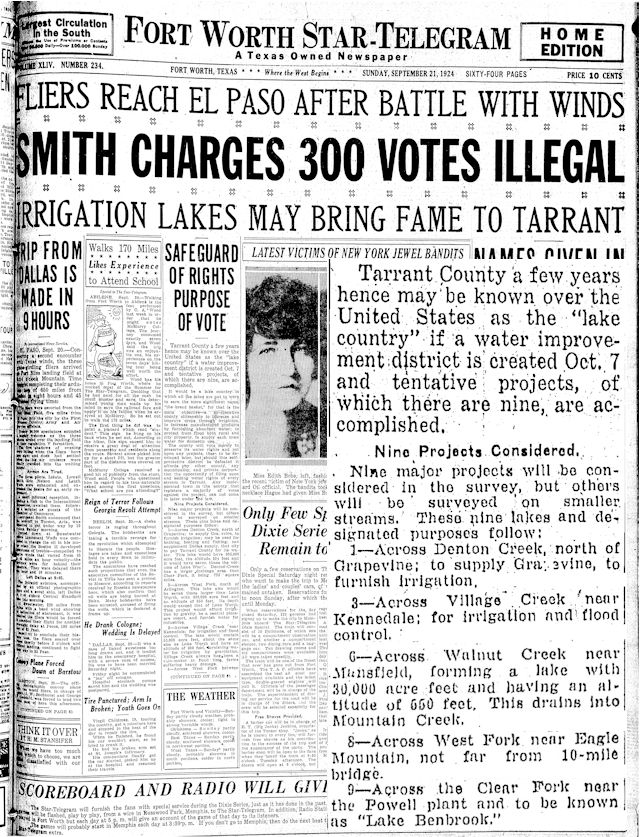

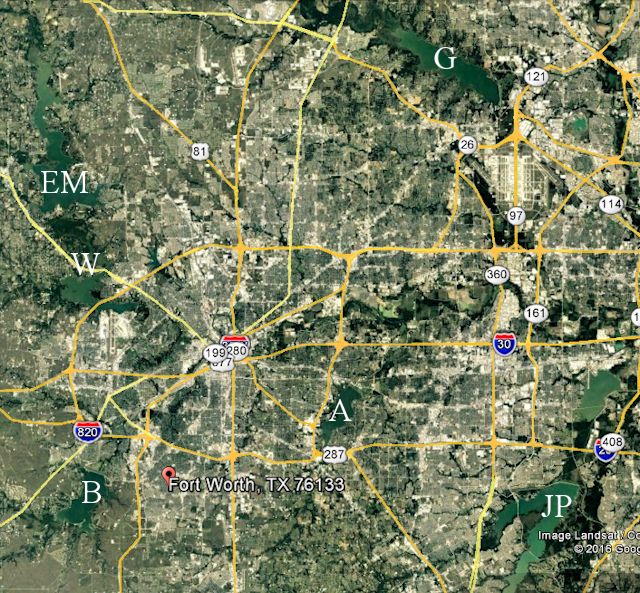

To provide that flood control, as well as water conservation, for the entire county, a water improvement district—with authority to levy taxes to finance water projects—was proposed in 1924. A front-page story headlined “Irrigation Lakes May Bring Fame to Tarrant” said this county could become known as “lake country” if voters approved the Tarrant County Water Improvement District and if the district built the nine lakes listed in the story. This remarkable “wish list” of proposed lakes contains all five of the county’s six big lakes built after Lake Worth. In the enlarged inset on the right, the five future lakes are 1. Grapevine, 3. Arlington, 6. Joe Pool, 8. Eagle Mountain, and 9. Benbrook. The newest of the five, Joe Pool, would be built sixty-two years after this “wish list” was published.

To provide that flood control, as well as water conservation, for the entire county, a water improvement district—with authority to levy taxes to finance water projects—was proposed in 1924. A front-page story headlined “Irrigation Lakes May Bring Fame to Tarrant” said this county could become known as “lake country” if voters approved the Tarrant County Water Improvement District and if the district built the nine lakes listed in the story. This remarkable “wish list” of proposed lakes contains all five of the county’s six big lakes built after Lake Worth. In the enlarged inset on the right, the five future lakes are 1. Grapevine, 3. Arlington, 6. Joe Pool, 8. Eagle Mountain, and 9. Benbrook. The newest of the five, Joe Pool, would be built sixty-two years after this “wish list” was published.

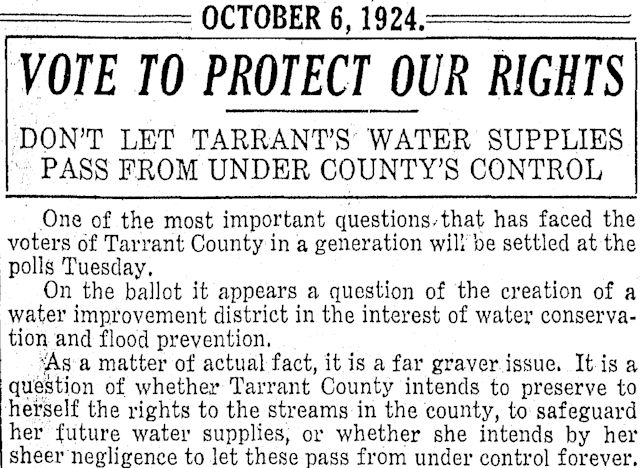

The Star-Telegram, in a front-page editorial, urged voters to approve the water improvement district to provide water conservation and flood control.

The Star-Telegram, in a front-page editorial, urged voters to approve the water improvement district to provide water conservation and flood control.

On October 7, 1924 voters of Tarrant County, by a ratio of four to one, did just that.

Second of the Big Six: Eagle Mountain

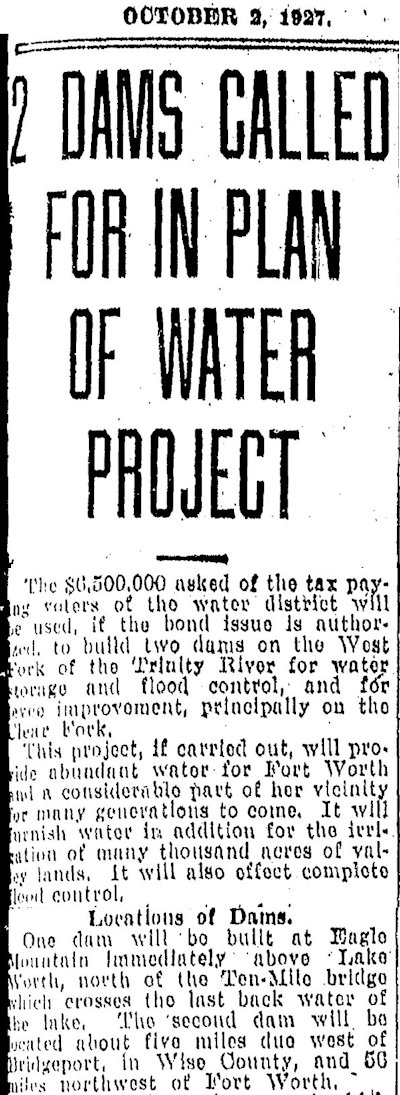

In 1927 county voters approved a $6.5 million ($92 million today) bond election to finance two lakes on the West Fork: Eagle Mountain above Lake Worth and Bridgeport above Eagle Mountain.

In 1927 county voters approved a $6.5 million ($92 million today) bond election to finance two lakes on the West Fork: Eagle Mountain above Lake Worth and Bridgeport above Eagle Mountain.

On May 1, 1928 the Texas State Board of Water Engineers granted a permit for the district to build the two lakes. Engineers began to survey water and flood lines for the two dam sites.

On May 1, 1928 the Texas State Board of Water Engineers granted a permit for the district to build the two lakes. Engineers began to survey water and flood lines for the two dam sites.

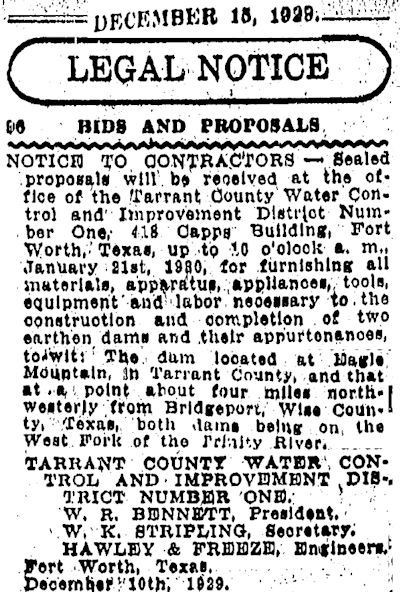

The district advertised for bids for construction of the dams in 1929. And, yes, in “Hawley & Freeze [sic], engineers” that’s the same John B. Hawley who in 1894 had recommended that Fort Worth build its first reservoir.

The district advertised for bids for construction of the dams in 1929. And, yes, in “Hawley & Freeze [sic], engineers” that’s the same John B. Hawley who in 1894 had recommended that Fort Worth build its first reservoir.

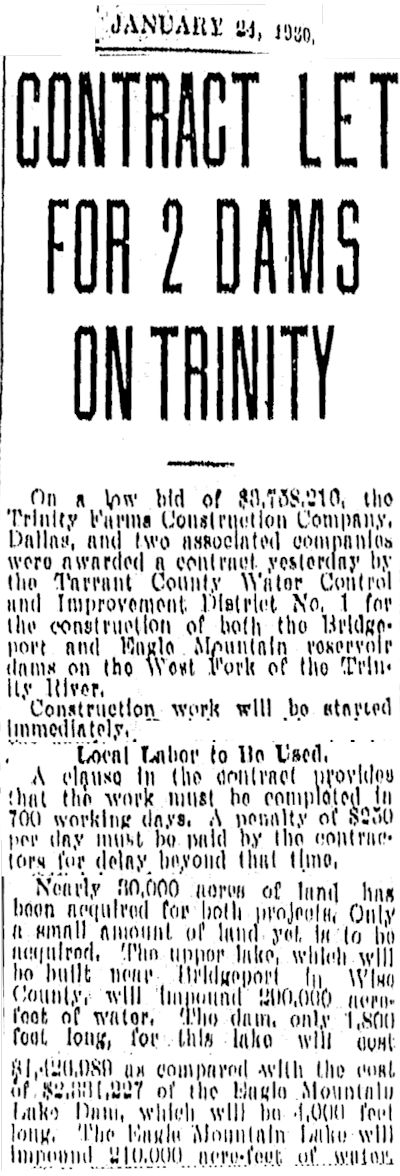

Early in 1930 contracts were awarded to three companies to build the Eagle Mountain and Bridgeport dams concurrently. The district had bought nearly thirty thousand acres of land for the two lakes. An officer of Trinity Farms Construction Company said a “small army” of perhaps two thousand men with axes might be employed to clear trees for the two lake sites. Lake Bridgeport would impound 290,000 acre-feet of water behind a dam eighteen hundred feet long; Eagle Mountain would impound 210,000 acre-feet behind a dam four thousand feet long. (1 acre-foot is 326,000 gallons.)

Early in 1930 contracts were awarded to three companies to build the Eagle Mountain and Bridgeport dams concurrently. The district had bought nearly thirty thousand acres of land for the two lakes. An officer of Trinity Farms Construction Company said a “small army” of perhaps two thousand men with axes might be employed to clear trees for the two lake sites. Lake Bridgeport would impound 290,000 acre-feet of water behind a dam eighteen hundred feet long; Eagle Mountain would impound 210,000 acre-feet behind a dam four thousand feet long. (1 acre-foot is 326,000 gallons.)

In most years, two huge lakes being built concurrently would dominate local news. But as this 1931 front-page feature shows, lakes Eagle Mountain and Bridgeport were just two of several major construction projects under way as Fort Worth roared into the 1930s (what depression?). Projects included the central post office, central fire station, Sinclair Building, Leonard’s Department Store, First Methodist Church, The Fair, Masonic Temple, Public Market, two grain elevators, and four railroad underpasses—all completed within the last two years or under construction.

In most years, two huge lakes being built concurrently would dominate local news. But as this 1931 front-page feature shows, lakes Eagle Mountain and Bridgeport were just two of several major construction projects under way as Fort Worth roared into the 1930s (what depression?). Projects included the central post office, central fire station, Sinclair Building, Leonard’s Department Store, First Methodist Church, The Fair, Masonic Temple, Public Market, two grain elevators, and four railroad underpasses—all completed within the last two years or under construction.

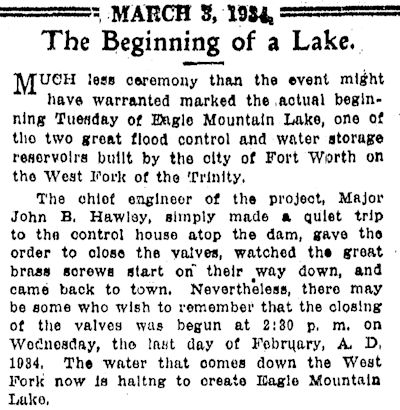

Lake Bridgeport was completed in 1931. The Eagle Mountain dam and reservoir were completed in 1934. Water impoundment began on February 28 as John B. Hawley, who must be considered the godfather of Fort Worth’s lakes, the Trinity River whisperer, “gave the order to close the valves, watched the great brass screws start on their way down, and came back to town.”

Lake Bridgeport was completed in 1931. The Eagle Mountain dam and reservoir were completed in 1934. Water impoundment began on February 28 as John B. Hawley, who must be considered the godfather of Fort Worth’s lakes, the Trinity River whisperer, “gave the order to close the valves, watched the great brass screws start on their way down, and came back to town.”

The West Fork of the Trinity was now constrained by three dams.

Third of the Big Six: Benbrook

In contrast, the Clear Fork remained undammed, a rogue river.

But the Clear Fork was about to meet its match.

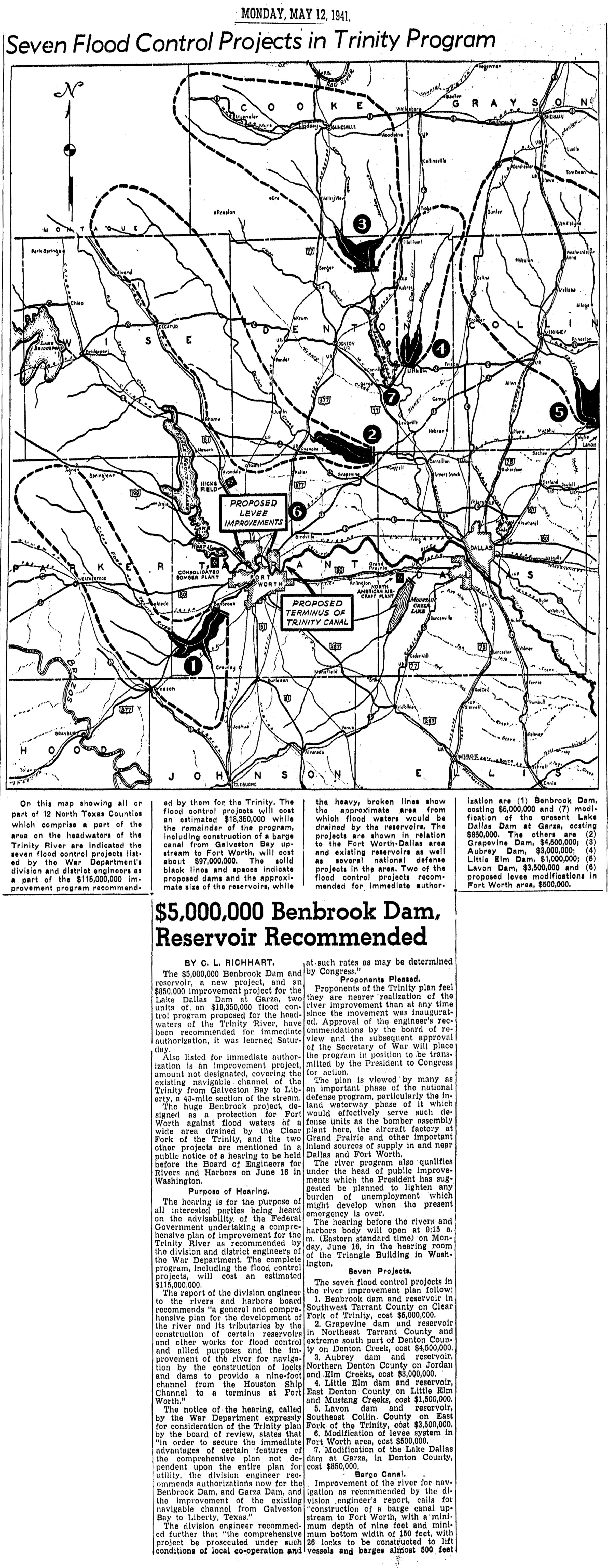

In 1936 the federal Flood Control Act made the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers the government’s lead flood control agency. In 1941 a flood control program for the Trinity River recommended that the Corps build two lakes that had been on the 1924 “wish list”: Benbrook on the Clear Fork and Grapevine on Denton Creek. The price tag for the Benbrook lake was $5 million ($83 million today). Also included in the recommendations was “construction of a barge canal upsteam to Fort Worth.”

In 1936 the federal Flood Control Act made the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers the government’s lead flood control agency. In 1941 a flood control program for the Trinity River recommended that the Corps build two lakes that had been on the 1924 “wish list”: Benbrook on the Clear Fork and Grapevine on Denton Creek. The price tag for the Benbrook lake was $5 million ($83 million today). Also included in the recommendations was “construction of a barge canal upsteam to Fort Worth.”

(C. L. Richhart was the Star-Telegram’s “Old Man River,” reporting on all things Trinity, especially the dream of canalizing the river.)

On March 1945 President Roosevelt signed the Rivers and Harbors Act, which provided for the construction of lakes Benbrook, Grapevine, Lavon, and Ray Roberts to control flooding of the Trinity River.

On March 1945 President Roosevelt signed the Rivers and Harbors Act, which provided for the construction of lakes Benbrook, Grapevine, Lavon, and Ray Roberts to control flooding of the Trinity River.

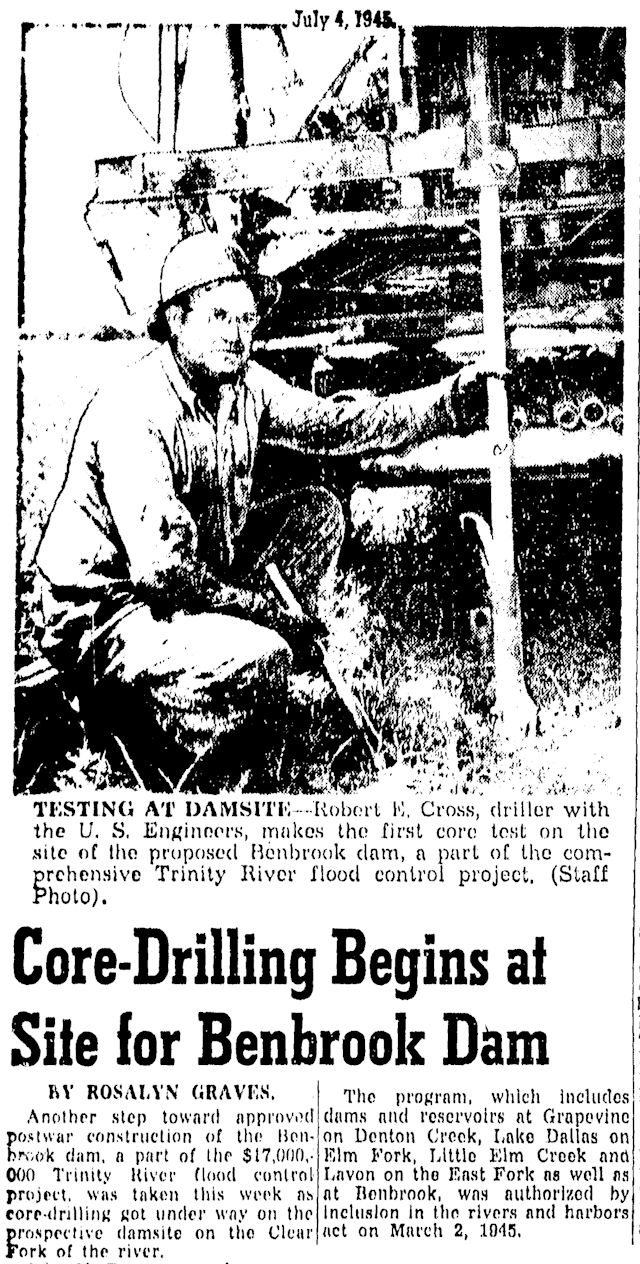

In July 1945 core drilling began at the prospective site of the Benbrook dam ten miles southwest of Fort Worth.

In July 1945 core drilling began at the prospective site of the Benbrook dam ten miles southwest of Fort Worth.

In 1946 the Benbrook Lake site was approved. The lake, covering twelve thousand acres of land, would control 416 square miles (80 percent) of the Clear Fork watershed and hold 258,630 acre-feet of water. The dam would be 9,200 feet long.

In 1946 the Benbrook Lake site was approved. The lake, covering twelve thousand acres of land, would control 416 square miles (80 percent) of the Clear Fork watershed and hold 258,630 acre-feet of water. The dam would be 9,200 feet long.

By the time ground was broken for Lake Benbrook in 1947, the price tag had risen to $12 million ($131 million today). Amon Carter, chairman of the executive committee of the Trinity Improvement Association, used a silver spade in the ceremony as bulldozers stood by idling.

By the time ground was broken for Lake Benbrook in 1947, the price tag had risen to $12 million ($131 million today). Amon Carter, chairman of the executive committee of the Trinity Improvement Association, used a silver spade in the ceremony as bulldozers stood by idling.

Two years later Benbrook Lake was still unfinished when the flood of 1949 ravaged Fort Worth in May. Engineers said the severity of the flood would have been lessened if the lake had been finished.

Two years later Benbrook Lake was still unfinished when the flood of 1949 ravaged Fort Worth in May. Engineers said the severity of the flood would have been lessened if the lake had been finished.

The Star-Telegram in an editorial said the flood of 1949 was yet more proof of the need for flood control on the Clear Fork. The three dams of lakes Worth, Eagle Mountain, and Bridgeport “had averted similar damage on the West Fork.”

The Star-Telegram in an editorial said the flood of 1949 was yet more proof of the need for flood control on the Clear Fork. The three dams of lakes Worth, Eagle Mountain, and Bridgeport “had averted similar damage on the West Fork.”

In October 1952 a Star-Telegram editorial noted a milestone: the closing of the gates of the Benbrook dam. The editorial was optimistic with a tinge of woe: “Benbrook Reservoir, if and when rain falls again, will harness the waters of the Trinity River’s Clear Fork.” Remember: In 1952 Texas was six years into the worst drought in its history. That drought was not be broken until 1957, just in time to fill up Lake Arlington (see below).

In October 1952 a Star-Telegram editorial noted a milestone: the closing of the gates of the Benbrook dam. The editorial was optimistic with a tinge of woe: “Benbrook Reservoir, if and when rain falls again, will harness the waters of the Trinity River’s Clear Fork.” Remember: In 1952 Texas was six years into the worst drought in its history. That drought was not be broken until 1957, just in time to fill up Lake Arlington (see below).

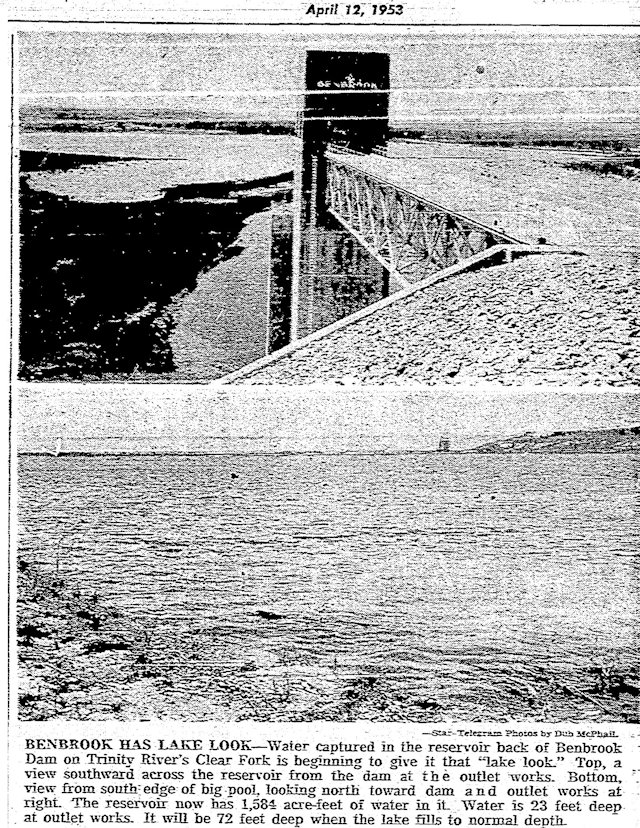

By April 1953, despite the drought, Lake Benbrook was holding 1,584 acre-feet of water and was beginning to have “that ‘lake look.’”

By April 1953, despite the drought, Lake Benbrook was holding 1,584 acre-feet of water and was beginning to have “that ‘lake look.’”

Fourth of the Big Six: Grapevine

Thirty miles northeast of Lake Benbrook was its twin, Lake Grapevine, located on sixteen thousand acres of land north of the city of Grapevine on Denton Creek, a tributary of the Elm Fork of the Trinity River. Both lakes had been approved as Corps projects in 1945 by the Rivers and Harbors Act.

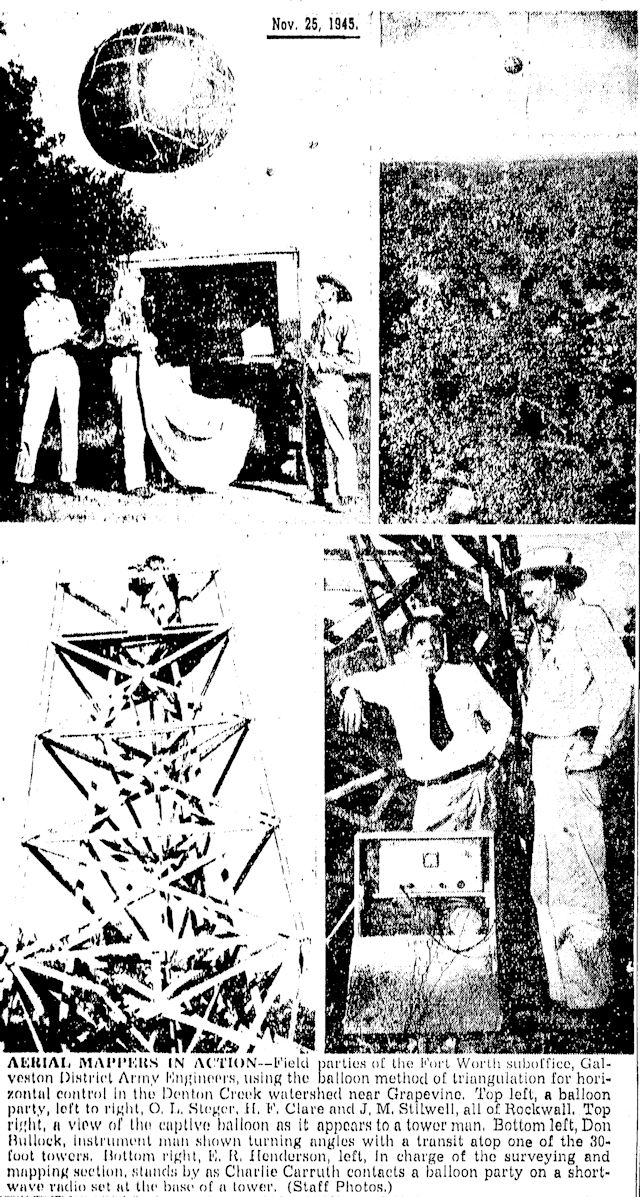

In 1945 Corps engineers used balloons to survey and map the watershed of Lake Grapevine’s Denton Creek.

In 1945 Corps engineers used balloons to survey and map the watershed of Lake Grapevine’s Denton Creek.

In 1947 it was time for Amon Carter to dig it again: He and two other men used a three-handled spade in the groundbreaking ceremony for the dam of Lake Grapevine.

In 1947 it was time for Amon Carter to dig it again: He and two other men used a three-handled spade in the groundbreaking ceremony for the dam of Lake Grapevine.

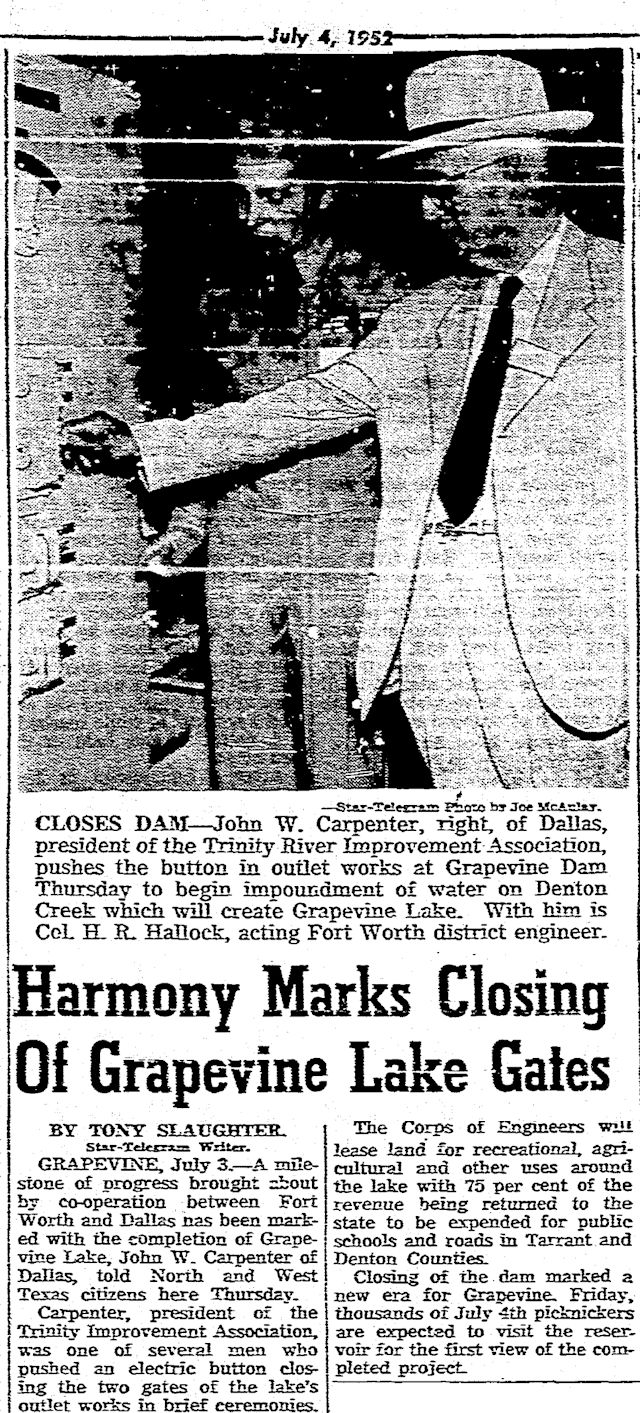

In July 1952 the floodgates of the new lake were closed. The fourth of Fort Worth’s six big lakes was completed.

In July 1952 the floodgates of the new lake were closed. The fourth of Fort Worth’s six big lakes was completed.

Fifth of the Big Six: Arlington

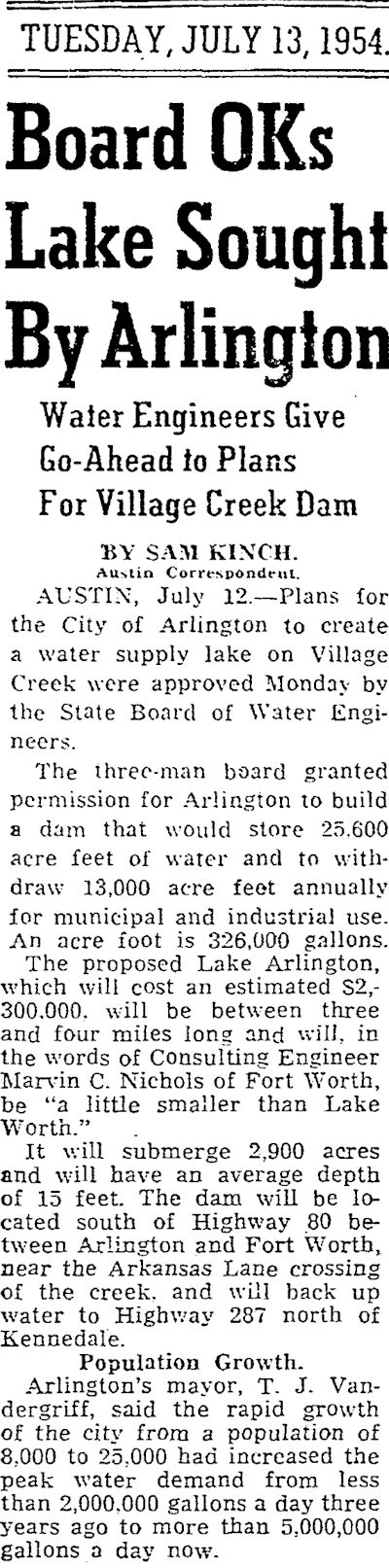

In 1954 leaders of the city of Arlington realized that their growing city would soon need a larger water supply.

That year the Texas State Board of Water Engineers approved Arlington’s plan to dam Village Creek and impound 25,800 acre-feet of water.

That year the Texas State Board of Water Engineers approved Arlington’s plan to dam Village Creek and impound 25,800 acre-feet of water.

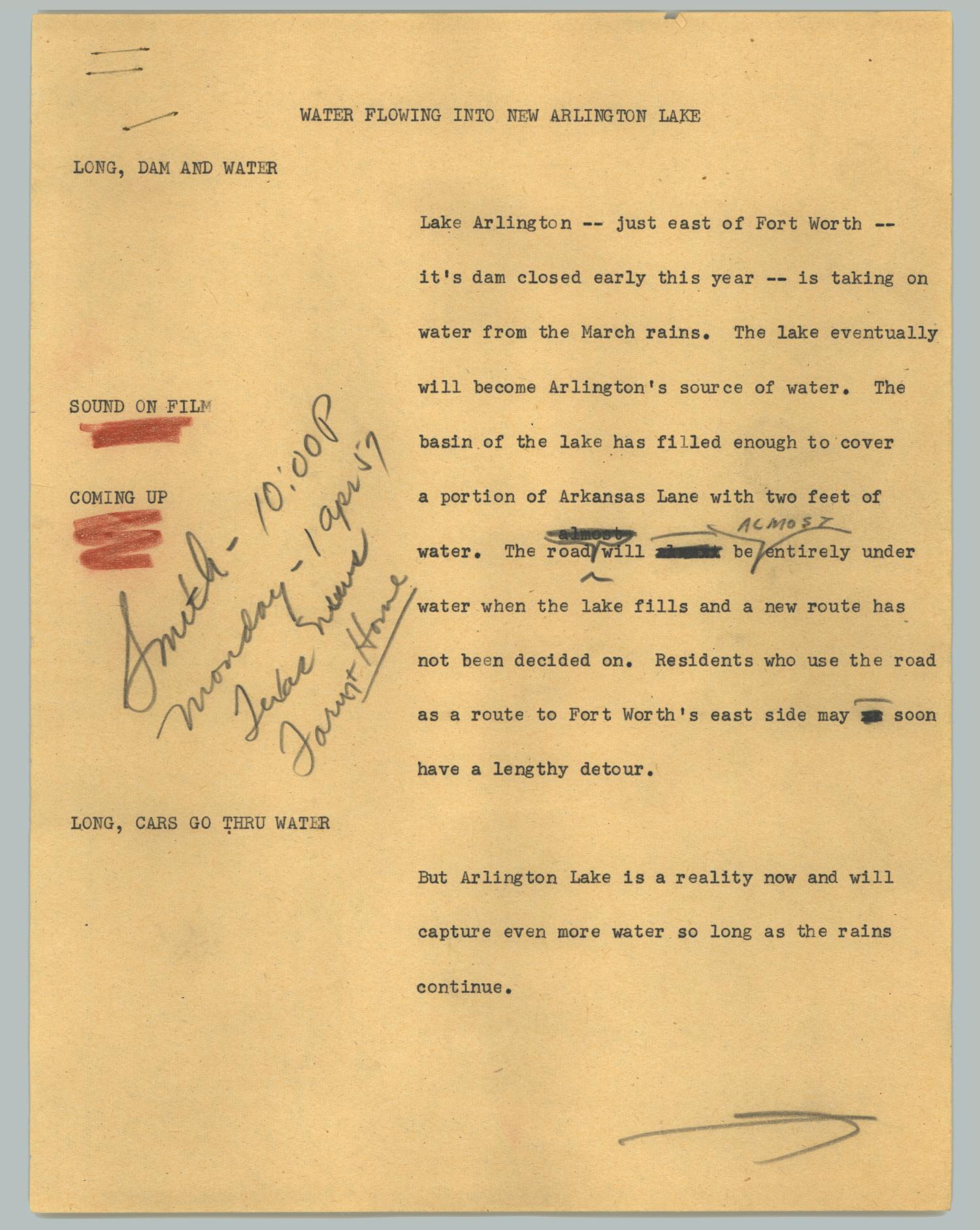

This script from a WBAP-TV news broadcast of April 1, 1957 says the Lake Arlington dam had been completed and was impounding water after 4.18 inches of rain had fallen in March, ending the eleven-year drought.

This script from a WBAP-TV news broadcast of April 1, 1957 says the Lake Arlington dam had been completed and was impounding water after 4.18 inches of rain had fallen in March, ending the eleven-year drought.

Lake Arlington has a separate post here.

Last of the Big Six: Joe Pool

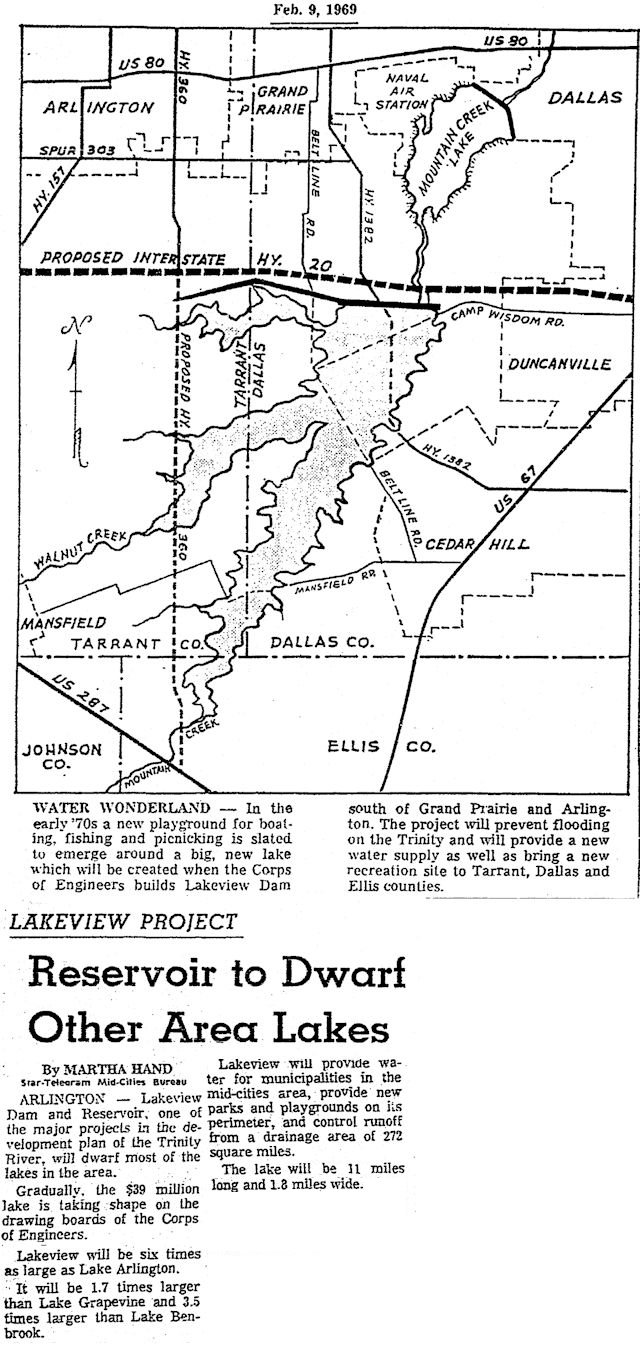

This lake southeast of Arlington is fed by Tarrant County’s Walnut Creek and Dallas County’s Mountain Creek, which are tributaries of the Trinity River. Joe Pool Lake began as a promise made in 1961 by U.S. Representative Joe Pool of Dallas. The project was ramrodded by a local citizens committee called the “Lakeview Planning Commission,” so-named because the lake originally was called “Lakeview.”

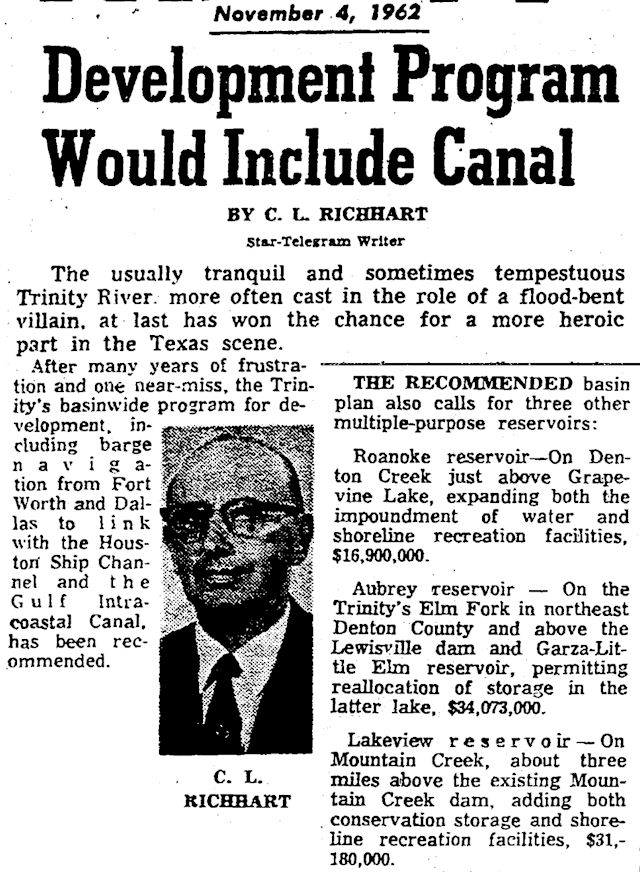

Twenty-one years after he had reported on plans for lakes Benbrook and Grapevine, the Star-Telegram’s C. L. Richhart was still on the Trinity River beat. In 1962 he reported that Lakeview was one of three lakes being considered as part of a Trinity River basinwide project (which again included the long-sought canalization of the river from the Gulf to Fort Worth).

Twenty-one years after he had reported on plans for lakes Benbrook and Grapevine, the Star-Telegram’s C. L. Richhart was still on the Trinity River beat. In 1962 he reported that Lakeview was one of three lakes being considered as part of a Trinity River basinwide project (which again included the long-sought canalization of the river from the Gulf to Fort Worth).

Congress approved the Lakeview project in 1965.

Congressman Joe Pool would not live to see the lake that eventually was named for him. He died in 1968.

Congressman Joe Pool would not live to see the lake that eventually was named for him. He died in 1968.

By 1969 Lakeview was still being planned by the Corps of Engineers with a price tag of $39 million ($260 million today).

By 1969 Lakeview was still being planned by the Corps of Engineers with a price tag of $39 million ($260 million today).

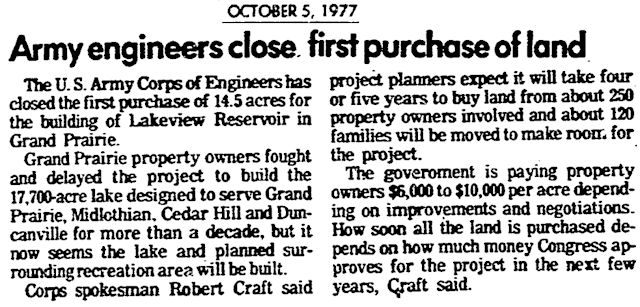

In 1977 the Corps finally began buying land on which to build Lakeview. It was a modest purchase: 14.5 of an eventual 17,700 acres.

In 1977 the Corps finally began buying land on which to build Lakeview. It was a modest purchase: 14.5 of an eventual 17,700 acres.

Construction of Lakeview Lake began in 1979—eleven years after Joe Pool died.

Construction of Lakeview Lake began in 1979—eleven years after Joe Pool died.

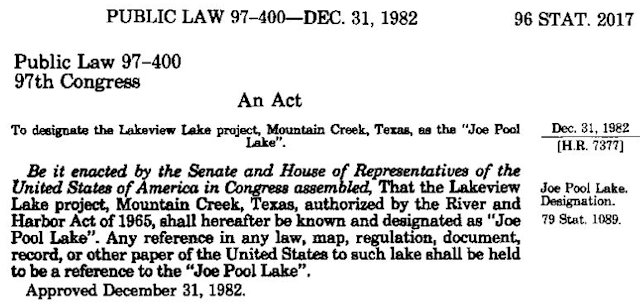

The lake since its earliest planning stage was called “Lakeview.” But relatives of Joe Pool told U.S. Representative Jim Wright of Fort Worth that they’d like the lake to be named for Pool. Toward that end, in 1982 Congress passed an act naming the lake for Joe Pool.

The lake since its earliest planning stage was called “Lakeview.” But relatives of Joe Pool told U.S. Representative Jim Wright of Fort Worth that they’d like the lake to be named for Pool. Toward that end, in 1982 Congress passed an act naming the lake for Joe Pool.

This name change caused some consternation among chambers of commerce and other local groups because they had printed maps and brochures that called the lake “Lakeview.”

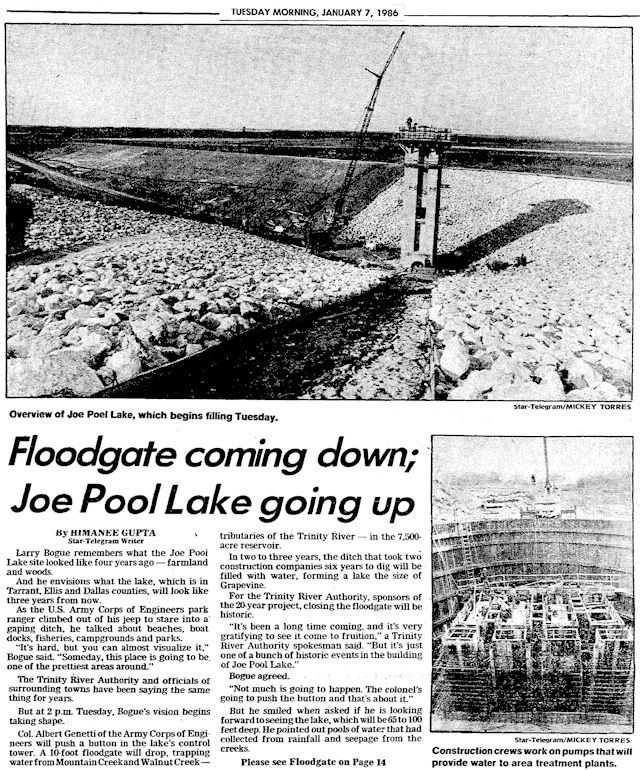

Construction of Joe Pool Lake was delayed by lack of funding, challenges by environmentalists, and squabbling among surrounding cities but finally was completed in December 1985. The floodgates of Joe Pool Lake were closed in January 1986, and it began to impound water. By the time the dust and litigation had settled, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Trinity River Authority, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and the Lakeview/Joe Pool Lake Planning Commission had collaborated to get the lake built.

Construction of Joe Pool Lake was delayed by lack of funding, challenges by environmentalists, and squabbling among surrounding cities but finally was completed in December 1985. The floodgates of Joe Pool Lake were closed in January 1986, and it began to impound water. By the time the dust and litigation had settled, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Trinity River Authority, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and the Lakeview/Joe Pool Lake Planning Commission had collaborated to get the lake built.

The last of Fort Worth’s six big lakes—built to ensure that the amount of water we get is, in the words of Goldilocks, “just right”—was finished seventy-two years after the first one.

The last of Fort Worth’s six big lakes—built to ensure that the amount of water we get is, in the words of Goldilocks, “just right”—was finished seventy-two years after the first one.