On the night of May 14, 1913 Tom Lee was shooting craps with Walter Moore and Pete Soles in the African-American section of Hell’s Half Acre. Lee had lost $100 when he decided to get out while he was still behind. (Part 1.)

The rest of that night Tom Lee (pictured) brooded. He suspected that Moore and Soles had cheated him. And Tom Lee was not one to turn the other cheek. He had to do enough of that as a bootblack at the Congress Barber Shop on Main Street, with its clientele of well-heeled white men. At age twenty-three Lee was a street-hardened scrapper in the African-American joints of the Acre and the African-American community on the east side of downtown. He had already been to prison for theft and two years earlier had killed one man and injured another after a dice game but was found to have acted in self-defense.

The rest of that night Tom Lee (pictured) brooded. He suspected that Moore and Soles had cheated him. And Tom Lee was not one to turn the other cheek. He had to do enough of that as a bootblack at the Congress Barber Shop on Main Street, with its clientele of well-heeled white men. At age twenty-three Lee was a street-hardened scrapper in the African-American joints of the Acre and the African-American community on the east side of downtown. He had already been to prison for theft and two years earlier had killed one man and injured another after a dice game but was found to have acted in self-defense.

On May 15, Lee would recall afterward, he was “half drunk” and “crazy mad.” He loaded a twelve-gauge double-barrel shotgun with turkey shot and went for a walk in the Acre.

Tom Lee was going to get $100 worth of revenge.

Plus interest.

His first stop was McCampbell’s barbecue stand on East 8th Street. As Lee expected, there he found Pete Soles. Soles and Lee exchanged a few unpleasantries, and Lee got in the last word with a blast of turkey shot to Soles’s chest.

One down, one to go.

Lee reloaded the double-barrel shotgun and continued his walk. At McGar’s saloon on Jones Street he found Walter Moore.

Another trigger pulled, another score settled.

Lee reloaded, cocked both triggers and, covering the frightened crowd of about twenty in McGar’s saloon, backed out the front door.

Tom Lee had just checked off the last item on his “to do” list for the day.

But the world just wouldn’t leave Tom Lee alone. Now came the hard part: escape.

As Lee walked on 8th Street he encountered Harold Murdock, age seventeen, who lived on Calhoun Street. Murdock had heard the gunshots and innocently had gone to investigate. Lee shot him.

A few blocks away police officer John Ogletree, on foot patrol in the Acre, had heard gunshots and was hurrying toward their source. Along the way Ogletree was warned by a passerby that Tom Lee was on a shooting rampage. “Tom Lee.” Ogletree was familiar with the name. At 8th and Grove streets (near today’s Intermodal Transportation Center) Ogletree encountered Lee.

“Without pausing, pistol in hand,” the Dallas Morning News wrote, “the policeman advanced toward the negro. Lee raised his gun and fired both barrels, the charges of turkey shot lodging in the policeman’s body above his hips.”

As Ogletree fell, fatally wounded, he fired four shots at Lee but missed. As Lee fled, a bystander, B. L. Pope, reloaded Ogletree’s pistol with bullets from the officer’s belt and fired six times at Lee.

As Ogletree fell, fatally wounded, he fired four shots at Lee but missed. As Lee fled, a bystander, B. L. Pope, reloaded Ogletree’s pistol with bullets from the officer’s belt and fired six times at Lee.

Lee again was not hit.

Lee fled into the maze of locomotives, boxcars, and tracks of the railyards on the east side of downtown. Then he encountered Dave Colton, age eighteen. Another blast from the shotgun.

By now an impromptu posse of armed civilians and police officers, “a mob of 2,000 pursuers,” the Star-Telegram wrote, was chasing Lee on foot, on horseback, and in automobiles. Railyard workers began blowing the whistles of locomotives to direct the posse to Lee as he fled.

Lee ducked into a culvert under the railroad tracks. Police arriving on the scene saw Lee disappear into the culvert and expected him to make his last stand there.

Suddenly they heard a muffled shot.

The fugitive Tom Lee had apprehended himself: He had slipped on the wet concrete and accidentally shot himself in the chin.

The tally of Tom Lee’s “half drunk” and “crazy mad” walk in Hell’s Half Acre: Officer John Ogletree and Walter Moore were dead. Pete Soles, Harold Murdock, and Dave Colton were wounded but would survive.

The tally of Tom Lee’s “half drunk” and “crazy mad” walk in Hell’s Half Acre: Officer John Ogletree and Walter Moore were dead. Pete Soles, Harold Murdock, and Dave Colton were wounded but would survive.

Tom Lee was out of action. But actions trigger reactions. And this reaction was swift and ugly.

Lee was taken to the medical college hospital nearby. When news spread that a black man who had killed a white policeman was at the hospital, an angry crowd gathered there. Police moved Lee to the county jail for his own safety.

About 9 p.m. an angry mob—as many as two thousand people, some of them “boys in knee pants”—gathered outside the front of the jail and demanded entrance. Some sections of the iron fence about the building were broken down. Members of the mob, historian Dr. Richard Selcer writes in A History of Fort Worth in Black & White, “most of them well-lubricated,” were “spoiling for a necktie party.”

They had come for Tom Lee. They carried “a long steel rail” to use as a battering ram. Some carried iron pickets wrenched from the jail fence. One man carried a bundle under his arm. In the bundle was a “stout rope.” As the mob pressed around the building Sheriff William Rea ordered that no one be admitted. He told the mob that Lee was not in the jail.

Twenty-five deputies and police officers stood guard at entrances to the building, now and then having to repel mobsters who pushed in en masse or attacked with a battering ram. One contingent of the mob went to the rear of the building and began using a “timber” to batter a door. From inside the door Rea told the mobsters to stop or else. The mob kept battering until the door yielded. A police officer inside fired a shot over the heads of the intruders. They retreated, and police secured the door.

The mob pelted lawmen with rocks and brickbats. Three police officers and Sheriff Rea were injured but stayed on the job.

The lawmen were outnumbered in Alamoic proportions. Rea called Governor Oscar Colquitt to ask for aid. Fifty militiamen—with orders to shoot to kill if necessary—arrived about 12:30 a.m.

But before the militia arrived, some members of the mob had already moved to a more vulnerable target: the African-American section of the Acre.

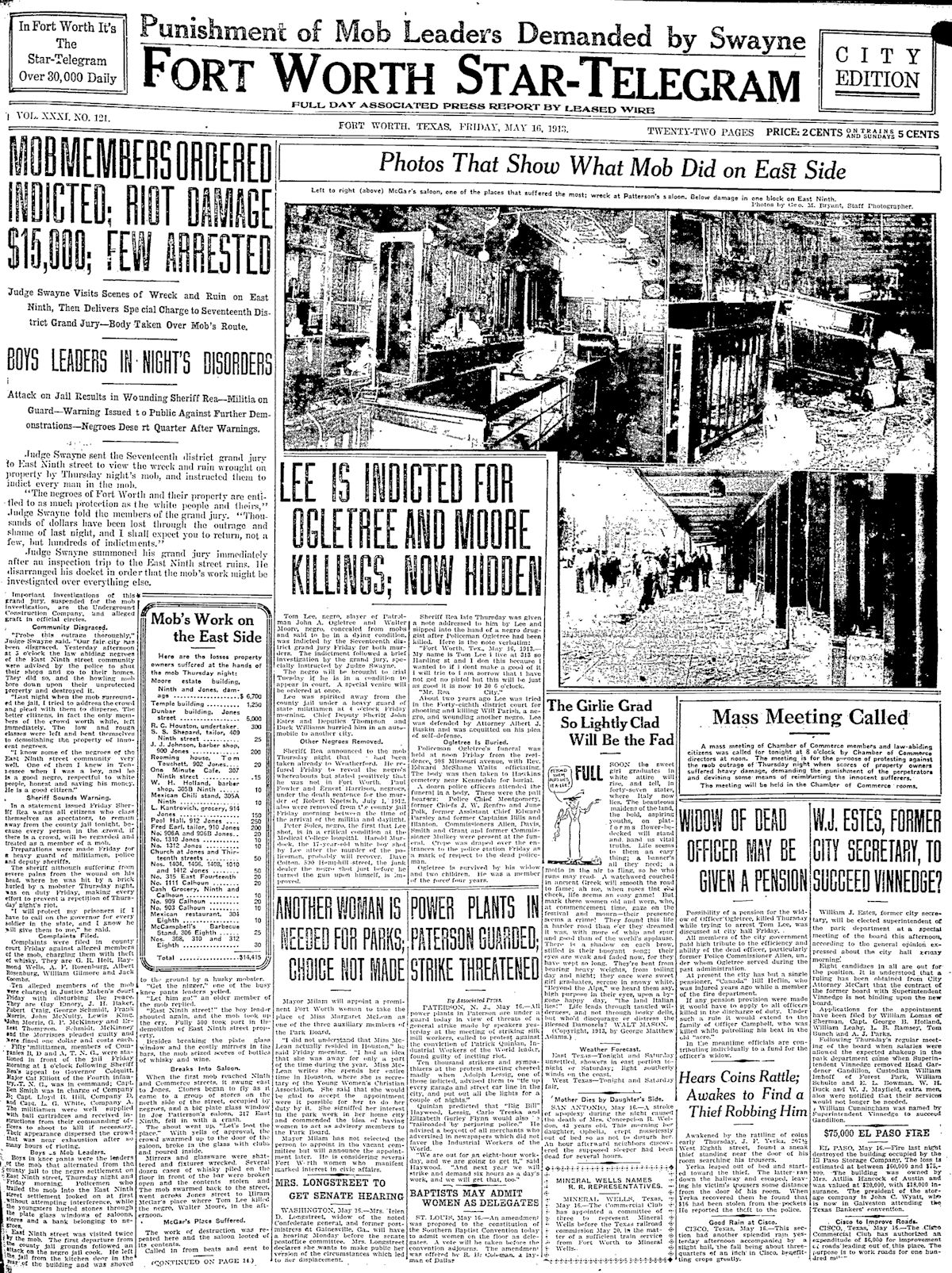

The front page of the Star-Telegram on May 16 told of the “wreck and ruin wrought on property” by “a howling mob.”

The front page of the Star-Telegram on May 16 told of the “wreck and ruin wrought on property” by “a howling mob.”

Because earlier that day a black man had killed a white police officer, the African-American community in the Acre had been on the alert. Indeed, police had advised African-American merchants in the Acre “to shut their shops and go to their homes.” Thus, unlike the county jail, “the negro settlement”—“every saloon, restaurant and store”—was largely deserted and undefended when the mob arrived. Damage done by rioters was more to property than to persons, although people were assaulted. For example, rioters stopped a streetcar on Samuels Avenue and another on Belknap Street and beat African-American passengers and smashed windows of the streetcars.

But most of the damage was done in the area around the intersection of East 9th and Jones streets.

Rioters, some drunk, some shouting racial slurs, smashed windows and doors with rocks and clubs, set set fire to buildings, stole or smashed cases of liquor. Display cases, glassware, mirrors, tables, and fixtures were smashed in saloons, restaurants, barber shops, pool halls, grocery stores, tenements, even a church and a funeral parlor.

The building that housed William “Gooseneck Bill” McDonald’s bank and the African-American Masonic lodge at East 9th and Jones streets was damaged. McCampbell’s barbecue stand and McGar’s saloon, where Tom Lee had wounded Pete Soles and killed Walter Moore earlier that day, were damaged.

Damage was estimated at $15,000 ($370,000 today).

Meanwhile, Tom Lee was indicted for two murders. But although the riot had been triggered by Lee’s killing of the white policeman, the prosecution saw a better chance of conviction for first-degree murder in Lee’s killing of the black man, Walter Moore. Under heavy guard Lee was spirited away to Denton. Also removed from the jail were Paul Fowler and Ernest Harrison (see Part 1).

And on May 16 officer John Ogletree was buried.

Police had warned the black community of the Acre about the possibility of a riot, but after that riot began, police were slow to come to the Acre and restore order. When people demanded an explanation, Mayor Robert Milam said that lawmen had been focused on defending the county jail while the riot raged in the Acre.

Judge James Swayne, among the more colorblind jurists of his time, sent his Seventeenth District Court grand jury to view the riot zone and demanded indictment of the rioters. The chamber of commerce called a mass meeting to protest the “mob outrage.”

A dozen or so rioters were charged with disturbing the peace, unlawful assembly, or public drunkenness, paid small fines, and were released. A few were charged with theft of whiskey.

No one was convicted of a major crime, historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster write in Written in Blood (Volume 2).

As Fort Worth, black and white, set about recovering from a day and night of mayhem, the legal system still had to deal with Tom Lee, whose actions had triggered so many reactions. As the mob at the jail had grown more menacing on the night of May 15, Lee had been moved to a tunnel that connected the jail with the courthouse and had been kept under guard there. Then he was moved by car to the Denton County jail.

As Fort Worth, black and white, set about recovering from a day and night of mayhem, the legal system still had to deal with Tom Lee, whose actions had triggered so many reactions. As the mob at the jail had grown more menacing on the night of May 15, Lee had been moved to a tunnel that connected the jail with the courthouse and had been kept under guard there. Then he was moved by car to the Denton County jail.

In Denton Lee told a Star-Telegram reporter: “Them two [Moore and Soles] robbed me of about $100 in a game of craps the day before the shooting, and I started out to get even. I’m glad I got them.”

Lee expressed regret for killing officer Ogletree and wounding “those two white boys.”

“I was half drunk and was crazy mad,” he said.

Lee told the reporter that he wanted quick justice.

And he got it. On May 22 he was returned to the Tarrant County jail and placed in a cell in the women’s ward. The injury to his chin caused by the gunshot was healing; he would be able to testify at his trial, which would begin the next day, May 23, just eight days after his “half drunk” and “crazy mad” rampage.

And he got it. On May 22 he was returned to the Tarrant County jail and placed in a cell in the women’s ward. The injury to his chin caused by the gunshot was healing; he would be able to testify at his trial, which would begin the next day, May 23, just eight days after his “half drunk” and “crazy mad” rampage.

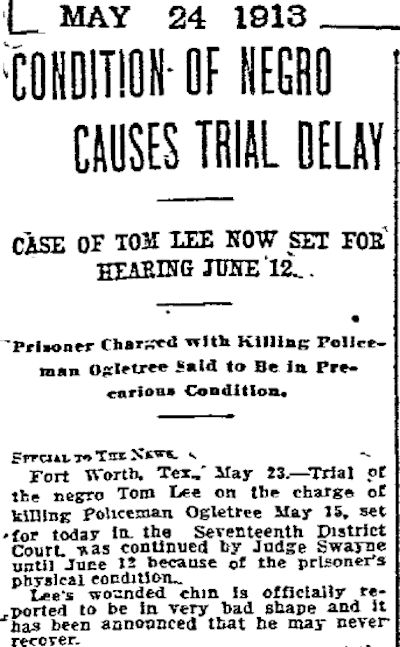

But on the day his trial for killing Walter Moore was to begin, Lee was deemed to be in “precarious condition.” The trial was postponed. Lee underwent an operation on his infected wound. His condition improved.

But on the day his trial for killing Walter Moore was to begin, Lee was deemed to be in “precarious condition.” The trial was postponed. Lee underwent an operation on his infected wound. His condition improved.

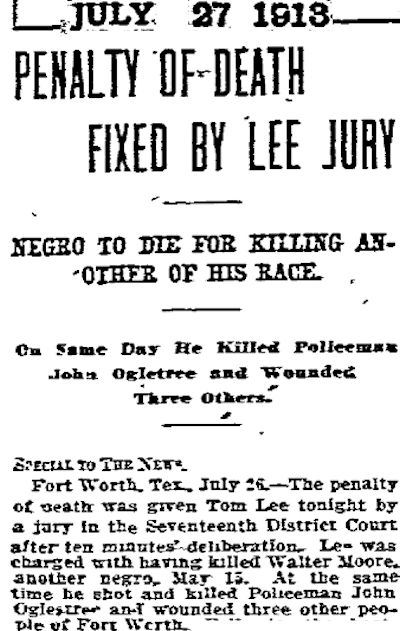

On July 25 Lee’s trial began. Everyone entering the courtroom was searched for weapons. The jury was twelve white men. Lee pleaded innocent by reason of insanity. The next day the jury took ten minutes to find Tom Lee guilty of murdering Walter Moore.

On July 25 Lee’s trial began. Everyone entering the courtroom was searched for weapons. The jury was twelve white men. Lee pleaded innocent by reason of insanity. The next day the jury took ten minutes to find Tom Lee guilty of murdering Walter Moore.

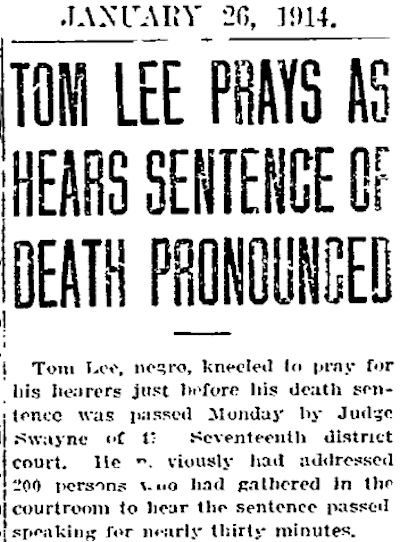

An appeals court upheld Lee’s conviction, and on January 26, 1914 the death sentence was pronounced. Tom Lee prayed. He also addressed the two hundred people present in the courtroom: “All you men before me now have white skins, but when you are in the clay your skins will turn black, too. . . . I hope I will meet you all in heaven.”

An appeals court upheld Lee’s conviction, and on January 26, 1914 the death sentence was pronounced. Tom Lee prayed. He also addressed the two hundred people present in the courtroom: “All you men before me now have white skins, but when you are in the clay your skins will turn black, too. . . . I hope I will meet you all in heaven.”

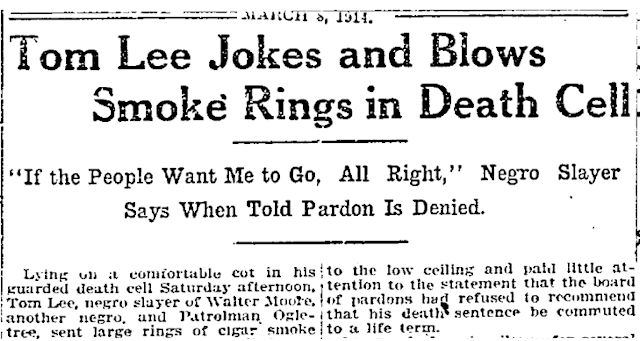

On March 7, 1914 Lee blew smoke rings as he was informed that his motion to have his death sentence commuted to life in prison had been denied.

On March 7, 1914 Lee blew smoke rings as he was informed that his motion to have his death sentence commuted to life in prison had been denied.

Two days later, March 9, the Star-Telegram printed an ad announcing that that night J. Frank Norris would preach on the topic “Why Tom Lee should not hang.”

Two days later, March 9, the Star-Telegram printed an ad announcing that that night J. Frank Norris would preach on the topic “Why Tom Lee should not hang.”

But that ad was a day late. Because on the morning of March 9 Sheriff Rea received a telegram from Governor Colquitt: “I decline to interfere in Tom Lee case.” Later that morning the jail building was surrounded by hundreds of (peaceful) people as Tom Lee prepared to die. He was baptized in his cell. He smoked a cigar. He was given a last shave, admonishing “the negro barber . . . not to interfere with his smoking too much.” On the gallows Tom Lee bowed to the 150 people present—including the widow of police officer John Ogletree—and said he would die like “a game little man.”

But that ad was a day late. Because on the morning of March 9 Sheriff Rea received a telegram from Governor Colquitt: “I decline to interfere in Tom Lee case.” Later that morning the jail building was surrounded by hundreds of (peaceful) people as Tom Lee prepared to die. He was baptized in his cell. He smoked a cigar. He was given a last shave, admonishing “the negro barber . . . not to interfere with his smoking too much.” On the gallows Tom Lee bowed to the 150 people present—including the widow of police officer John Ogletree—and said he would die like “a game little man.”

At 11:20 a.m. he did.

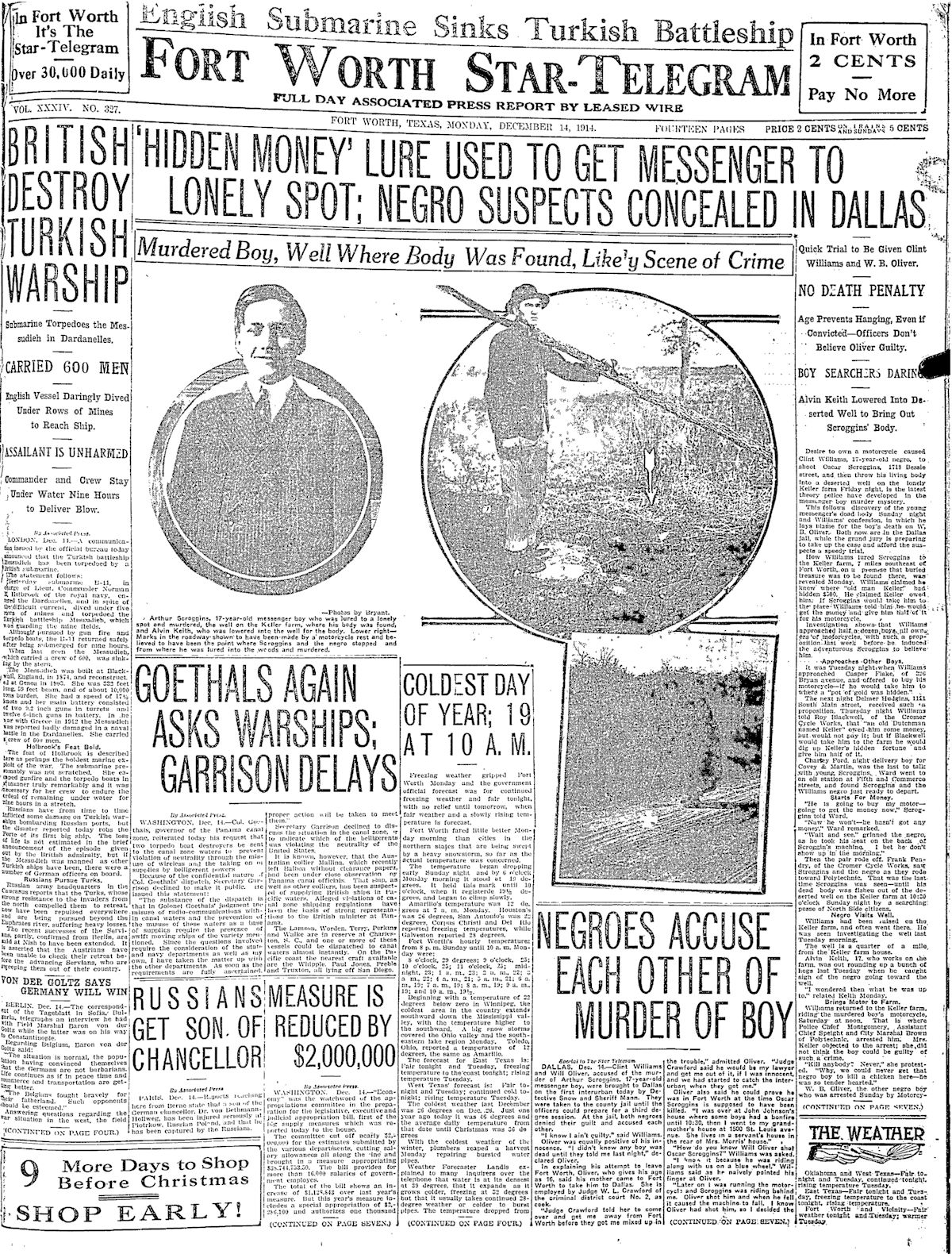

On Saturday, December 12, 1914 messenger boy Oscar Scroggins, age seventeen, of 1718 Bessie Street was reported missing by his stepfather.

On Saturday, December 12, 1914 messenger boy Oscar Scroggins, age seventeen, of 1718 Bessie Street was reported missing by his stepfather.

Police suspected that Scroggins had been killed and his body hidden in “the lonely bottoms or gulches” of the Polytechnic area because a friend of Scroggins told police that on Friday night he had seen Scroggins riding his motorcycle “on the Polytechnic road.” Following behind Scroggins on a bicycle was an African-American male whom the friend recognized. A woman living in the area told police that she heard “three boyish screams, followed by a pistol shot” Friday night. On Saturday police found Scroggins’s motorcycle in the possession of the “negro, aged 19, who was seen following him.” The suspect told police he had bought the motorcycle from Scroggins for $100, but the suspect’s family told police that the suspect did not have that much money. Police also knew that the motorcycle was not worth $100. Another friend of Scroggins told police that Scroggins said that “a negro had offered him $100 for his motorcycle and he was going out to the country with him to get the money.” Police were guarding the suspect in an undisclosed substation for fear of “another race riot” such as the one triggered by the murder of officer Ogletree.

Police suspected that Scroggins had been killed and his body hidden in “the lonely bottoms or gulches” of the Polytechnic area because a friend of Scroggins told police that on Friday night he had seen Scroggins riding his motorcycle “on the Polytechnic road.” Following behind Scroggins on a bicycle was an African-American male whom the friend recognized. A woman living in the area told police that she heard “three boyish screams, followed by a pistol shot” Friday night. On Saturday police found Scroggins’s motorcycle in the possession of the “negro, aged 19, who was seen following him.” The suspect told police he had bought the motorcycle from Scroggins for $100, but the suspect’s family told police that the suspect did not have that much money. Police also knew that the motorcycle was not worth $100. Another friend of Scroggins told police that Scroggins said that “a negro had offered him $100 for his motorcycle and he was going out to the country with him to get the money.” Police were guarding the suspect in an undisclosed substation for fear of “another race riot” such as the one triggered by the murder of officer Ogletree.

On Sunday night Scroggins’s body was found in a well on the Keller family farm seven miles southeast of Fort Worth.

On Sunday night Scroggins’s body was found in a well on the Keller family farm seven miles southeast of Fort Worth.

Police arrested two suspects: Clint Williams and Will Oliver. Williams told police that he and Scroggins had been riding on the motorcycle near the Keller farm when Will Oliver came up behind them on a bicycle and asked to ride the motorcycle. Scroggins told Oliver “to go to thunder,” Williams said, and Oliver shot Scroggins and dragged his body to the well. Williams, explaining why he was in possession of Scroggins’s motorcycle afterward, said he had ridden it back to town to get away from the crime scene after Oliver killed Scroggins.

Police arrested two suspects: Clint Williams and Will Oliver. Williams told police that he and Scroggins had been riding on the motorcycle near the Keller farm when Will Oliver came up behind them on a bicycle and asked to ride the motorcycle. Scroggins told Oliver “to go to thunder,” Williams said, and Oliver shot Scroggins and dragged his body to the well. Williams, explaining why he was in possession of Scroggins’s motorcycle afterward, said he had ridden it back to town to get away from the crime scene after Oliver killed Scroggins.

Will Oliver denied having any knowledge of the crime.

Williams later led police to the well on the Keller farm. Williams had once lived and worked on the farm. Medical evidence showed that the victim had still been alive when dropped into the well.

Several other boys—all of whom owned motorcycles—told police that Clint Williams had told them that he knew where “old man Keller” had buried $500 (alternately, “a pot of gold”) on Keller’s farm. They said Williams told them that if they would take him to the farm on their motorcycle, he would find the buried treasure and give them half of it in exchange for their motorcycle.

Because of talk of lynching, both suspects were taken to the Dallas County jail for safekeeping.

An important point: Police said Williams was seventeen, but his mother said he was sixteen.

On December 15 Clint Williams confessed that he, not Will Oliver, had shot Oscar Scroggins and dumped his body in the well.

On December 15 Clint Williams confessed that he, not Will Oliver, had shot Oscar Scroggins and dumped his body in the well.

“At the edge of the woods at the Keller place I told him [Scroggins] I had to get off the motorcycle a minute. . . . I had the gun in my hip pocket. I got it out and shot him in the back. He hollered ‘Oh! Oh! Oh!’ three times.”

Williams told police where they could find the pistol, which he had discarded near the crime scene. Police said a bullet found in Williams’s pocket and a slug removed from Scroggins’s body matched bullets found in the pistol.

Will Oliver was released from custody.

When Clint Williams went on trial in January 1915 he pleaded not guilty, and his attorneys contended that because Williams was only fifteen at the time of the crime he could not be given the death penalty. The prosecution produced witnesses, including a probation officer, who testified that Williams was at least eighteen.

When Clint Williams went on trial in January 1915 he pleaded not guilty, and his attorneys contended that because Williams was only fifteen at the time of the crime he could not be given the death penalty. The prosecution produced witnesses, including a probation officer, who testified that Williams was at least eighteen.

In the courtroom, the Star-Telegram noted, Williams “wore short trousers and sat huddled down in his chair, making him look smaller and more youthful.”

On January 12, 1915, amid heavy security in the courtroom, Clint Williams was found guilty of murder. The announcement was “greeted by an uproar of cheers from the crowd which packed the courtroom.” The judge, in his charge to the jury, had said that if jurors concluded that the defendant was younger than seventeen, they could not assess the death penalty. Jury foreman J. R. Fuller said the jury deliberated only the age of Williams, not his guilt. Fuller said that on the second ballot, all jurors agreed that Williams was at least seventeen.

On January 12, 1915, amid heavy security in the courtroom, Clint Williams was found guilty of murder. The announcement was “greeted by an uproar of cheers from the crowd which packed the courtroom.” The judge, in his charge to the jury, had said that if jurors concluded that the defendant was younger than seventeen, they could not assess the death penalty. Jury foreman J. R. Fuller said the jury deliberated only the age of Williams, not his guilt. Fuller said that on the second ballot, all jurors agreed that Williams was at least seventeen.

Clint Williams was given the death penalty.

Two days later Williams recanted his confession to a Star-Telegram reporter. Williams said he did not kill Oscar Scroggins but knew who did. But he would not name names.

Two days later Williams recanted his confession to a Star-Telegram reporter. Williams said he did not kill Oscar Scroggins but knew who did. But he would not name names.

Williams appealed the death penalty, claiming that the state had failed to prove that he had been seventeen years old at the time of the murder. Williams claimed that he had been only sixteen.

The state contended that the last digit in the year of Williams’s birth as written in a family Bible had been altered from 1897 to 1899 and that, in fact, Williams had been eighteen at the time of the murder. The state also contended that prior to the crime Williams had told people he was twenty years old.

An appeals court upheld the sentence of death.

An appeals court upheld the sentence of death.

On the morning of August 5, 1915 Clint Williams put on the blue serge suit that the county provided for his execution. He lit a cigar and insisted on having his shoes shined. On the gallows Williams kept the cigar in his mouth until a jailer put the noose around his neck and pulled the black hood over his head.

On the morning of August 5, 1915 Clint Williams put on the blue serge suit that the county provided for his execution. He lit a cigar and insisted on having his shoes shined. On the gallows Williams kept the cigar in his mouth until a jailer put the noose around his neck and pulled the black hood over his head.

Sheriff Nace Mann sprang the trapdoor of the gallows at 11:15 a.m.

The mother, brother, and stepfather of victim Oscar Scroggins witnessed the execution.

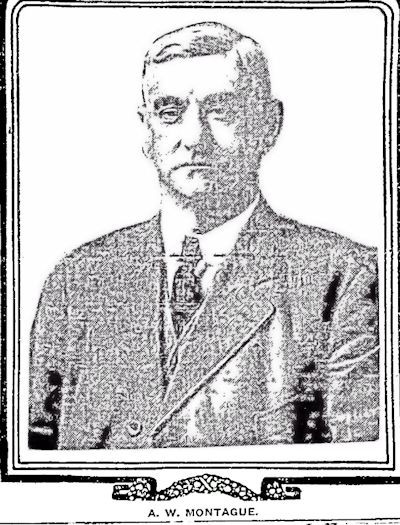

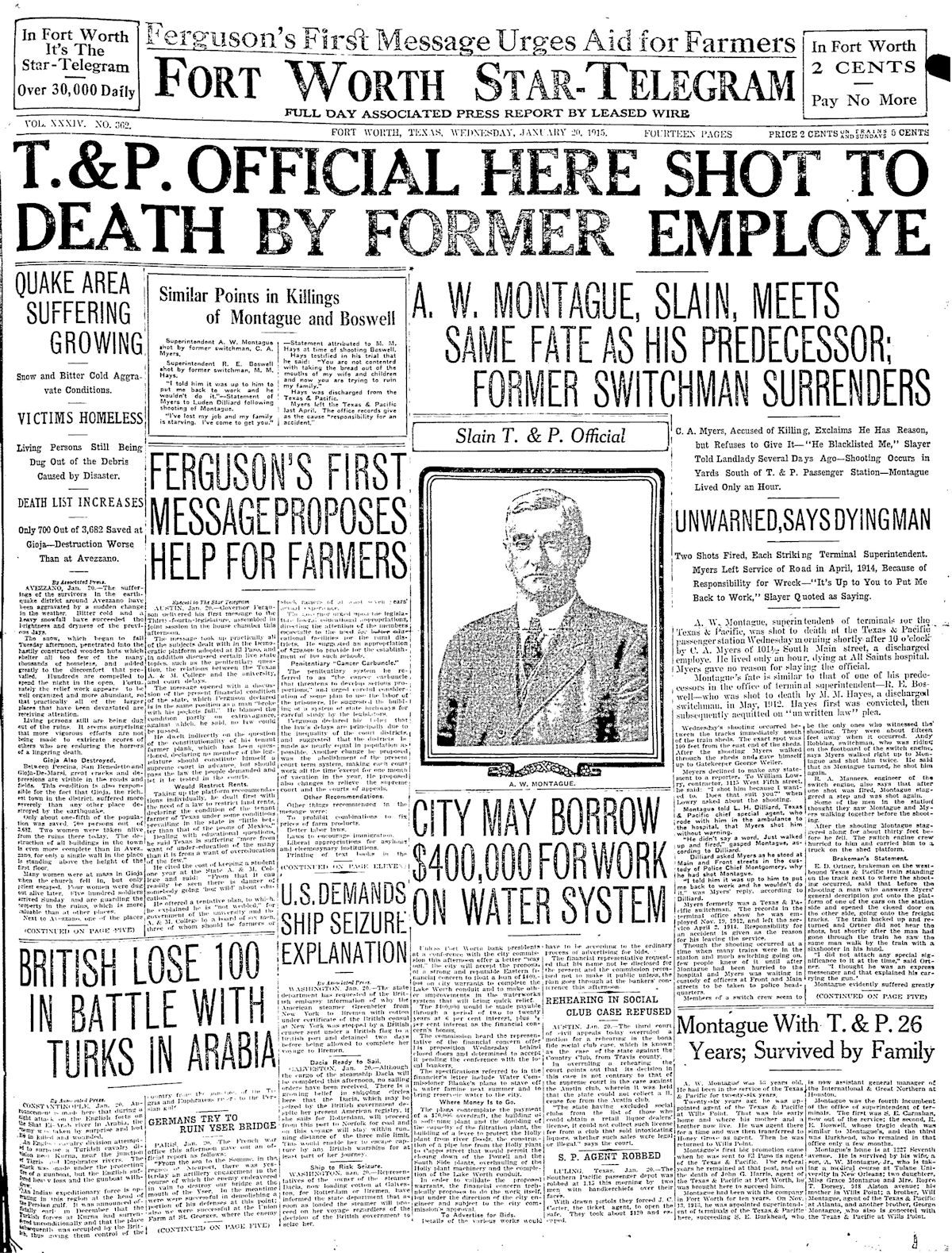

On April 2, 1914 an empty boxcar derailed in the Texas & Pacific railyard at the south end of downtown. Damage done: $20. T&P superintendent of terminals A. W. Montague investigated the derailment and concluded that switchman C. A. Myers was at fault.

On April 2, 1914 an empty boxcar derailed in the Texas & Pacific railyard at the south end of downtown. Damage done: $20. T&P superintendent of terminals A. W. Montague investigated the derailment and concluded that switchman C. A. Myers was at fault.

Myers, fifty-eight, was a veteran trainman, having worked as fireman, brakeman, and switchman around the country for various railroad companies.

Myers, fifty-eight, was a veteran trainman, having worked as fireman, brakeman, and switchman around the country for various railroad companies.

Nonetheless, Montague fired Myers.

In August of 1914 Myers told Montague that he was still out of work and asked Montague if he could use Montague as a reference when seeking employment. Montague consented.

Myers, who lived at the Globe Hotel on South Main Street near the T&P railyard, went to Kansas City and was hired by a railroad but was fired after fifteen days because his application was not approved. He then got a job with another railroad in Kansas City but was fired after twelve days for the same reason.

Myers came back to Fort Worth and remained out of work.

Shortly after 10 a.m. on January 20, 1915 Myers walked up to Montague in the T&P railyard and shot him two times.

Shortly after 10 a.m. on January 20, 1915 Myers walked up to Montague in the T&P railyard and shot him two times.

Myers then walked through the train sheds to the T&P passenger station and surrendered to the stationmaster.

Montague said of Myers as Montague was rushed to All Saints Hospital: “He didn’t say a word. Just walked up and fired.”

Myers, asked why he shot Montague, said, “I told him it was up to him to put me back to work, and he wouldn’t do it.”

A. W. Montague died in the hospital. Montague, fifty-three, was the second T&P superintendent of terminals to be killed by a discharged switchman. And Montague was the second railroad man Myers had shot: He had served a year in prison for shooting a switchman in 1911.

A veteran T&P trainman assessed the case: “Every mistake does not mean dismissal. Superintendent Montague was very considerate and did not remove a man unless safety demanded it or there was good reason. There is no such thing as a blacklist. The law requires that a record of a man’s service be kept, and this must be furnished when it is called for.”

On the night of the killing, a group of thirty men arrived at the Tarrant County jail and demanded entrance to search for Myers. Sheriff’s deputies spirited Myers out a back door into a car and drove him to the Dallas County jail. The group was then allowed to search the jail, including the tunnel connecting the jail and the courthouse (where Tom Lee had been kept during the siege of the jail in 1913). The crowd disbanded upon not finding Myers.

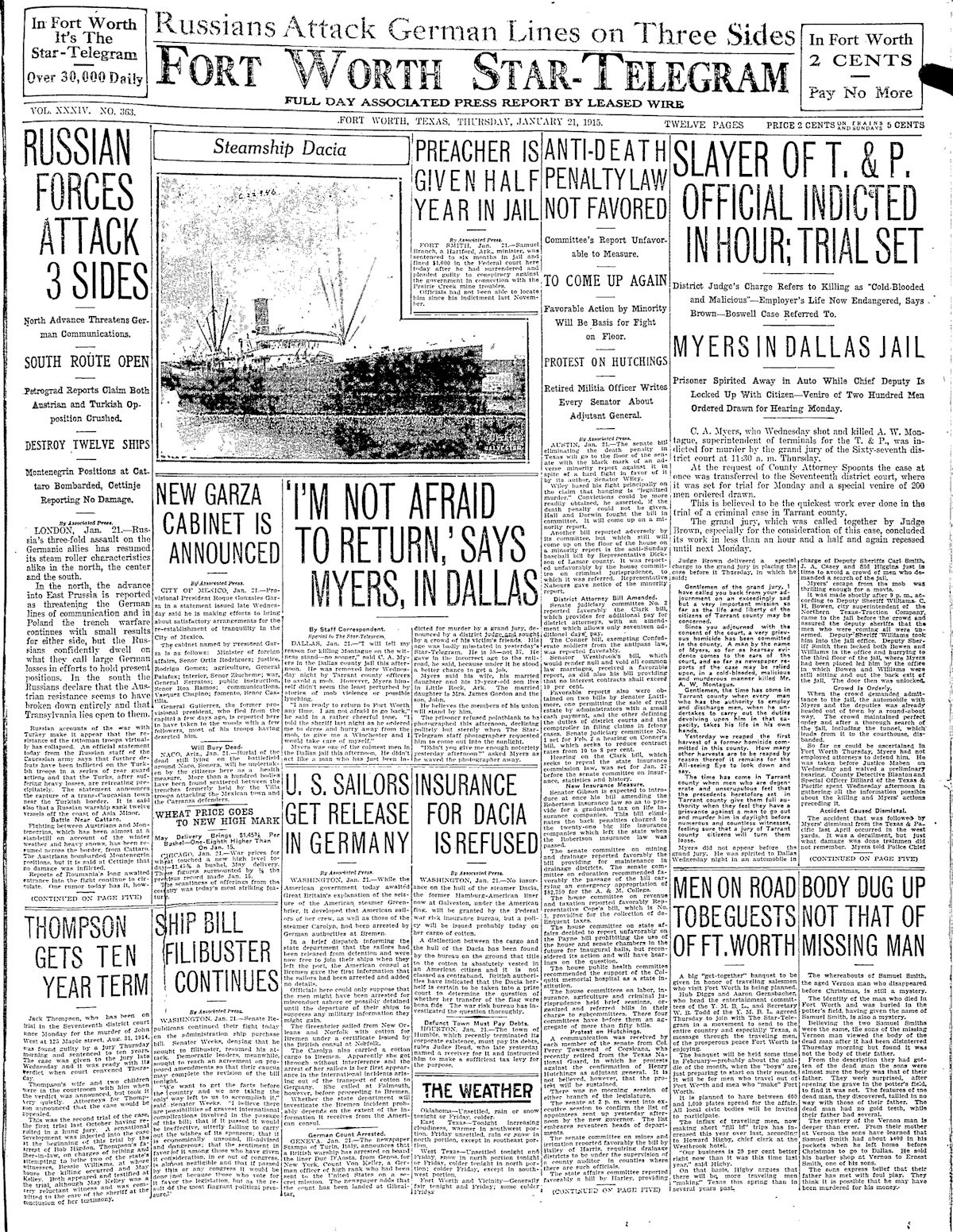

On January 21, the day after the shooting, Myers was indicted.

On January 21, the day after the shooting, Myers was indicted.

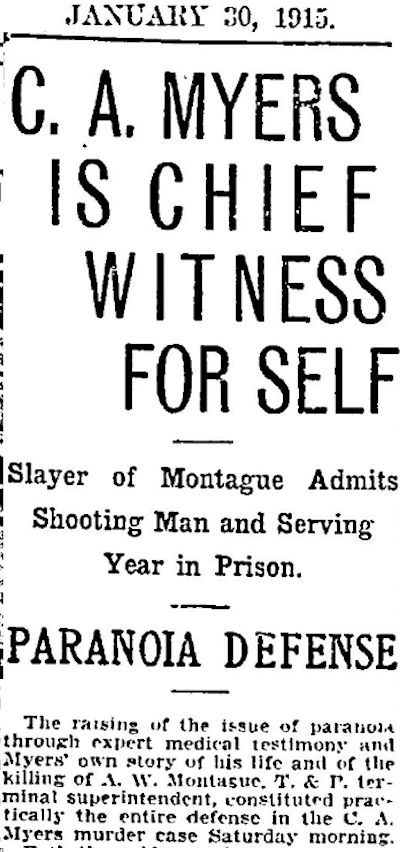

On January 29 testimony began in the murder trial of C. A. Myers. His attorneys claimed that Myers was innocent by reason of insanity (paranoia). A doctor testified that he had examined Myers and found that Myers exhibited some symptoms of paranoia, but the doctor said he could not say more without a more thorough examination.

On January 29 testimony began in the murder trial of C. A. Myers. His attorneys claimed that Myers was innocent by reason of insanity (paranoia). A doctor testified that he had examined Myers and found that Myers exhibited some symptoms of paranoia, but the doctor said he could not say more without a more thorough examination.

On the witness stand Myers recalled that after losing the two jobs in Kansas City and returning to Fort Worth he had encountered Montague on a street and accused Montague of blacklisting him.

Montague, Myers said, denied the accusation.

Myers testified that on three occasions he asked Montague to rehire him.

Each time Montague refused.

“The next time I met him was in the depot the morning I shot him. I asked him again if he wouldn’t put me back to work. He told me I couldn’t work for the T&P as long as he was superintendent of terminals. The next time I saw him I walked up to him and told him I was going to kill him and shot him.”

The prosecution contended that Myers had shot Montague because Montague had refused to rehire Myers, not because Montague had blacklisted Myers.

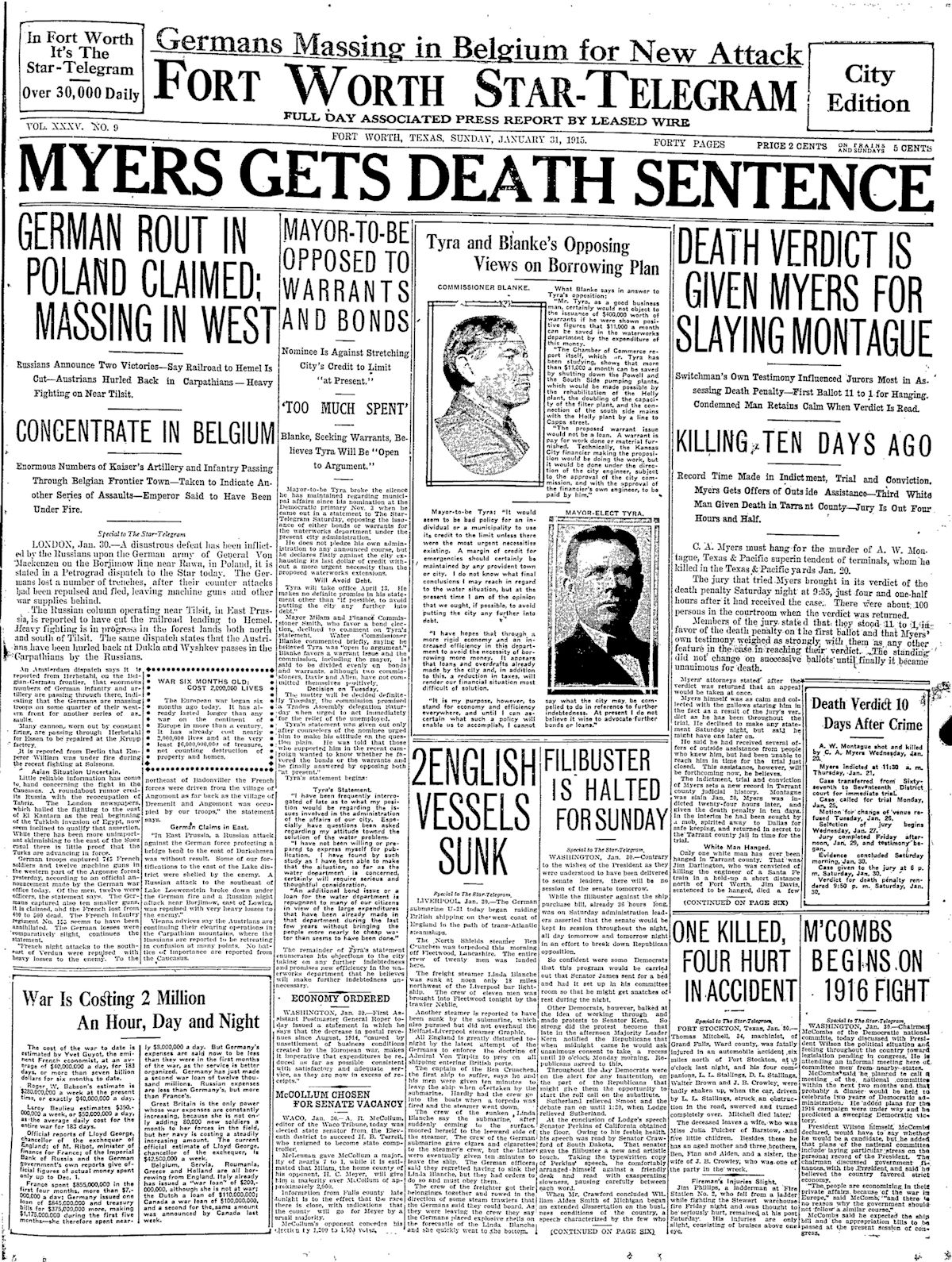

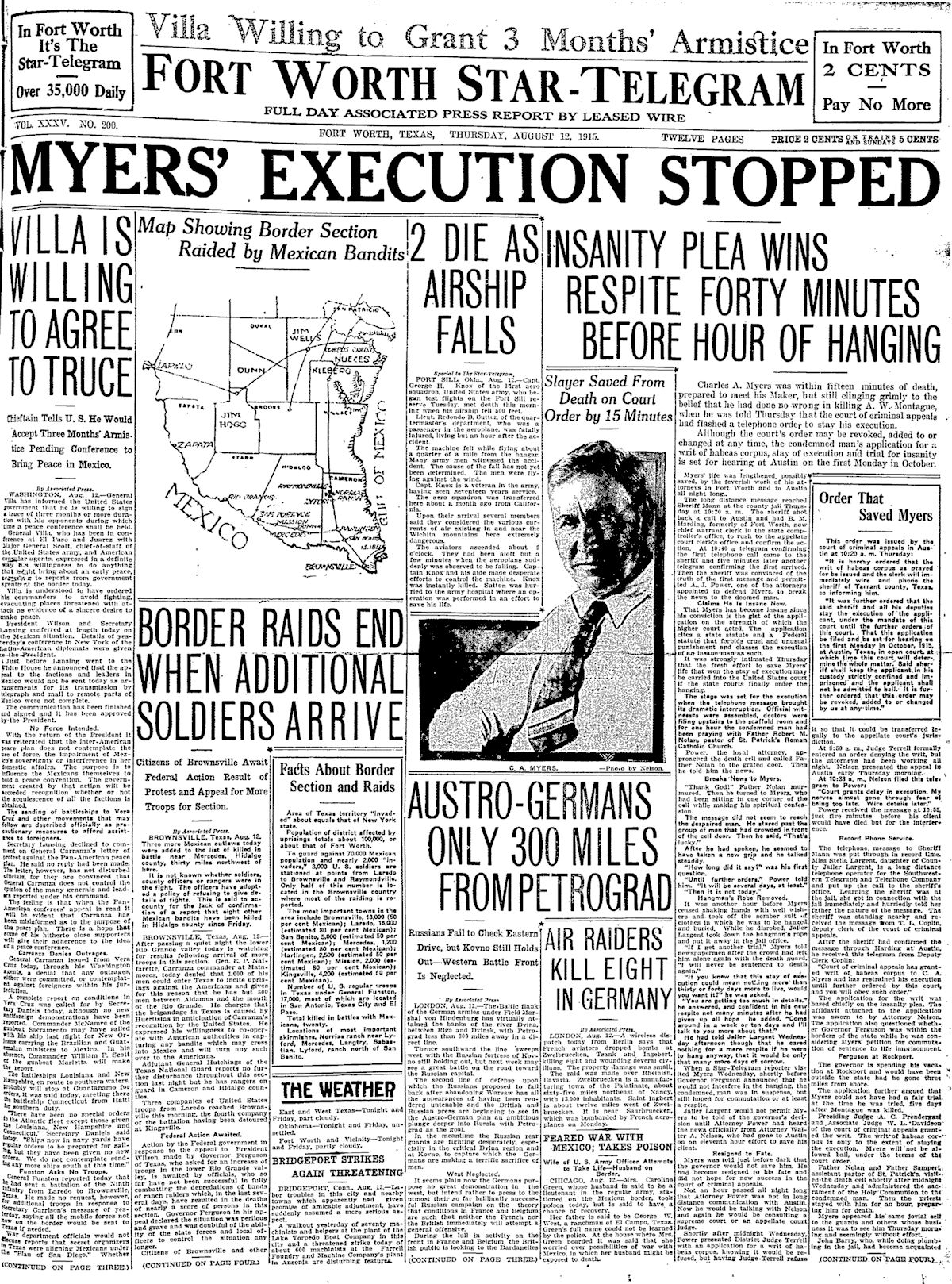

On January 30, just ten days after the killing, C. A. Myers was found guilty and sentenced to hang. The jury said that Myers’s own testimony was a major factor in voting for the death penalty. The Star-Telegram wrote that Myers was only the third white man to be sentenced to death in Tarrant County and that only one of the three—James Darlington (see Part 1)—had actually been hanged.

On January 30, just ten days after the killing, C. A. Myers was found guilty and sentenced to hang. The jury said that Myers’s own testimony was a major factor in voting for the death penalty. The Star-Telegram wrote that Myers was only the third white man to be sentenced to death in Tarrant County and that only one of the three—James Darlington (see Part 1)—had actually been hanged.

In June, after the Court of Criminal Appeals upheld Myers’s conviction, the family of his victim paid a special guard to prevent Myers from escaping from the jail because of its “weakened condition.”

In June, after the Court of Criminal Appeals upheld Myers’s conviction, the family of his victim paid a special guard to prevent Myers from escaping from the jail because of its “weakened condition.”

Meanwhile the Socialists of Fort Worth continued to oppose the death penalty, specifically citing the case of Myers.

Meanwhile the Socialists of Fort Worth continued to oppose the death penalty, specifically citing the case of Myers.

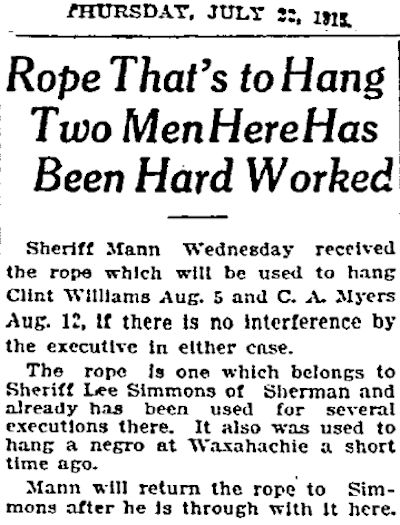

Neighbors borrow cups of sugar. Students borrow homework. Sheriffs borrow hanging ropes. In July Tarrant County Sheriff Nace Mann borrowed a hanging rope from Sheriff Simmons of Grayson County to use in the executions of Clint Williams and C. A. Myers.

Neighbors borrow cups of sugar. Students borrow homework. Sheriffs borrow hanging ropes. In July Tarrant County Sheriff Nace Mann borrowed a hanging rope from Sheriff Simmons of Grayson County to use in the executions of Clint Williams and C. A. Myers.

Meanwhile Myers’s attorneys continued his legal fight, contending that Myers had become insane after his conviction and that the law forbids the execution of an insane person.

In August Judge James Swayne, who had presided over Myers’s trial and sentenced him to death, received several anonymous death threats by letter. Myers said he thought the letters were sent by his enemies to prevent the commutation of his sentence.

On August 5, when Clint Williams was hanged in the county jail, the gallows was visible from Myers’s cell. Myers placed a blanket over the front of the cell to block his view.

A week later, on the morning of August 12, it was Myers’s turn. Dressed in the suit he would be hanged and buried in, Myers was praying with Father Robert Nolan of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The rope was on the gallows; the people who would witness the execution and the doctors who would pronounce him dead were arriving.

Forty minutes before Myers was scheduled to hang, the Court of Criminal Appeals stayed the execution and ordered a trial to determine Myers’s sanity.

Forty minutes before Myers was scheduled to hang, the Court of Criminal Appeals stayed the execution and ordered a trial to determine Myers’s sanity.

In days to come Myers was examined in his cell by twenty-two doctors, including Dr. Clay Johnson.

At Myers’s sanity hearing in September, every doctor called to the stand said Myers was sane.

But Myers did find one supporter: His wife testified that she thought he was insane.

On October 2 the jury found C. A. Myers to be sane; the death sentence was validated.

During the night of November 9 C. A. Myers, alone in his dark cell, took a shard of glass from its hiding place and slashed his wrist. He had bled only a pint before he was discovered and treated.

During the night of November 9 C. A. Myers, alone in his dark cell, took a shard of glass from its hiding place and slashed his wrist. He had bled only a pint before he was discovered and treated.

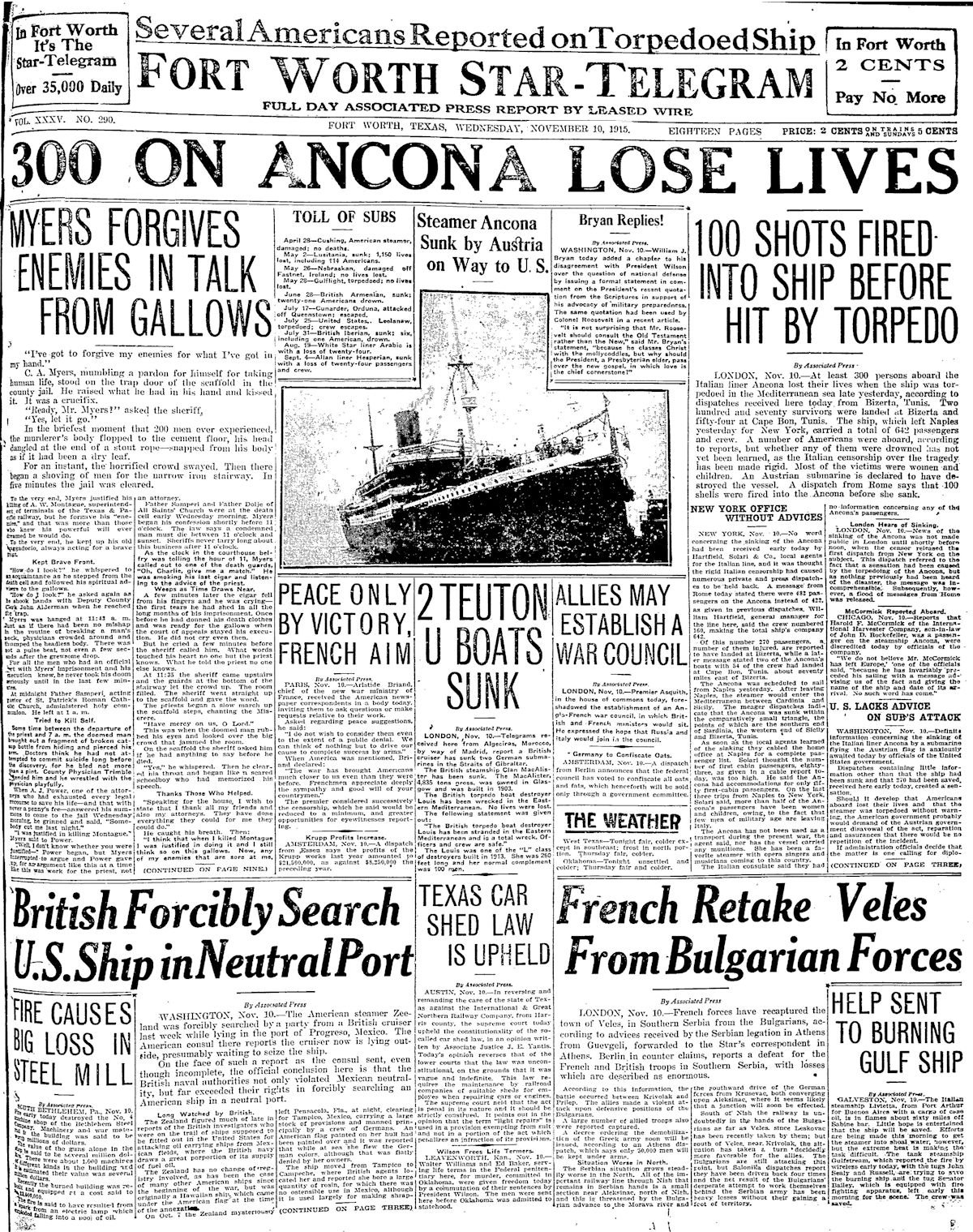

A few hours later on the morning of November 10, 1915 C. A. Myers smoked a cigar as a priest talked with him. Soon after Myers stood on the gallows holding a crucifx. Before the black hood was pulled over his head, he spoke to the two hundred witnesses, referring often to his “enemies”: “I’ve got to forgive my enemies . . . There are a whole lot of my enemies here. I can see five or six right here. . . . Gentlemen, I don’t know how many enemies I have in this audience . . .”

He also said: “I think that when I killed Montague I was justified in doing it, and I still think so on this gallows.”

Sheriff Nace Mann used the borrowed rope at 11:43 a.m., and, by the Star-Telegram’s reckoning, C. A. Myers became the second white man to be hanged in Tarrant County.

Myers, at age fifty-eight, was more than twice the age of most of the men profiled in this post.

Unlike the hanging of James Darlington, which the Dallas Morning News had critiqued with the headlines “All Details Were Perfect” and “No Hitch Occurred,” the hanging of C. A. Myers did not go off without a hitch.

Myers was a heavy man, and the rope was new and unforgiving. News of the grotesque mishap was carried around the nation.

Perhaps that is one reason why not a single mourner attended his funeral.

Perhaps that is one reason why not a single mourner attended his funeral.

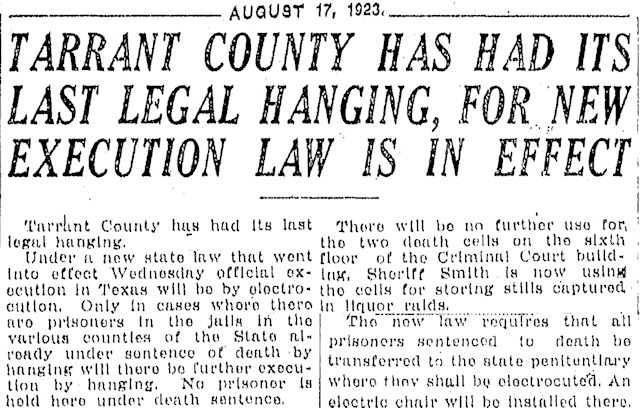

Fast-forward to 1923. The Tarrant County gallows, which had hanged at least ten men since 1874, was retired as a new law mandated (1) that all executions in the state be performed at the state penitentiary and (2) that electrocution, not hanging, be the method.

Fast-forward to 1923. The Tarrant County gallows, which had hanged at least ten men since 1874, was retired as a new law mandated (1) that all executions in the state be performed at the state penitentiary and (2) that electrocution, not hanging, be the method.

By 1923 prohibition had been the law of the land for three years. The two death cells in the Criminal Courts Building would now be used to store stills confiscated in raids.

The average age of these ten men hanged for their crimes: mid-twenties. When robbery was the motive, the average monetary gain: less than one hundred dollars.

This grim sampling of crime and punishment notwithstanding, legal hangings in Tarrant County may have been outnumbered by illegal hangings (some of which no doubt went unreported), such as the lynching of Anthony Bewley, Tom Vickery, and Fred D. Rouse.

![]() The name of officer John Ogletree is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.

The name of officer John Ogletree is engraved on the wall of the Fort Worth Police and Firefighters Memorial in Trinity Park.