On December 19, 1885 Comanche Chief Quanah Parker came to Fort Worth. With Parker was father-in-law Yellow Bear, the father of Wec-Keah, Parker’s first wife.

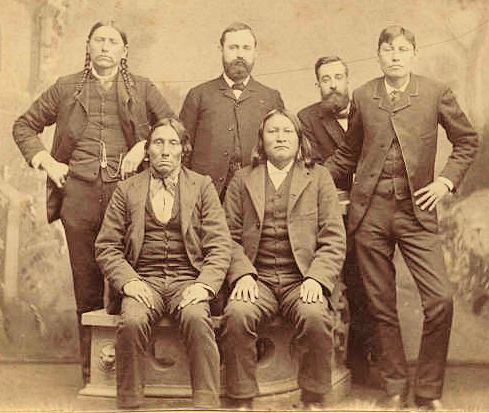

The two men arrived on the Fort Worth & Denver City train from Indian Territory. They had come to Fort Worth to meet with Captain Lee Hall, federal agent for the Wichita, Kiowa, and Comanches, to discuss the collection of money that was due to their tribes from white cattlemen who had leased tribal reservation lands. Quanah Parker, son of Cynthia Ann Parker and Comanche Chief Peta Nocona, was about thirty-six at the time. The Fort Worth Daily Gazette described Quanah Parker as “by far the most influential man in the Comanche nation, well-to-do, intelligent, and liberal and a fast friend of the whites.” Among those whites was Burk Burnett. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room.)

The two men arrived on the Fort Worth & Denver City train from Indian Territory. They had come to Fort Worth to meet with Captain Lee Hall, federal agent for the Wichita, Kiowa, and Comanches, to discuss the collection of money that was due to their tribes from white cattlemen who had leased tribal reservation lands. Quanah Parker, son of Cynthia Ann Parker and Comanche Chief Peta Nocona, was about thirty-six at the time. The Fort Worth Daily Gazette described Quanah Parker as “by far the most influential man in the Comanche nation, well-to-do, intelligent, and liberal and a fast friend of the whites.” Among those whites was Burk Burnett. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room.)

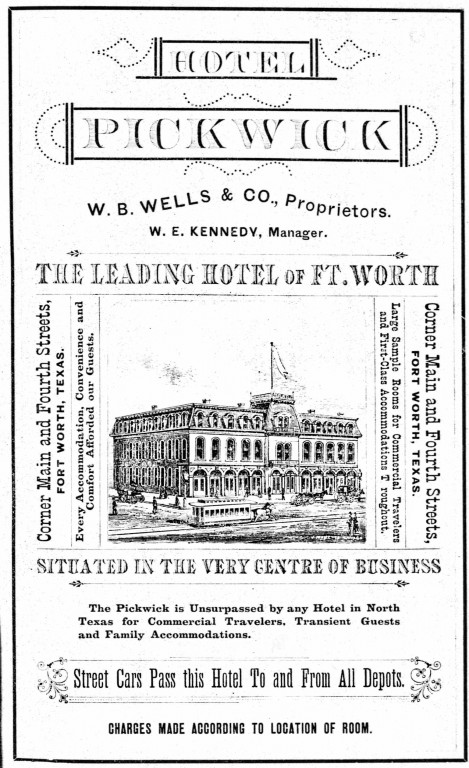

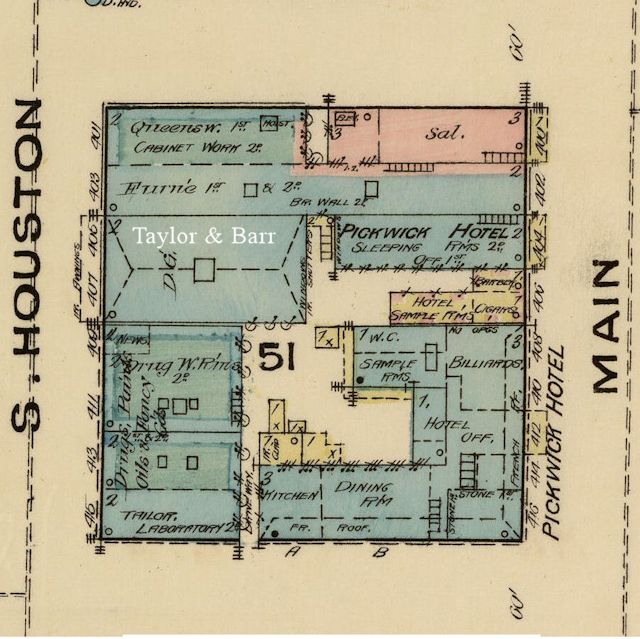

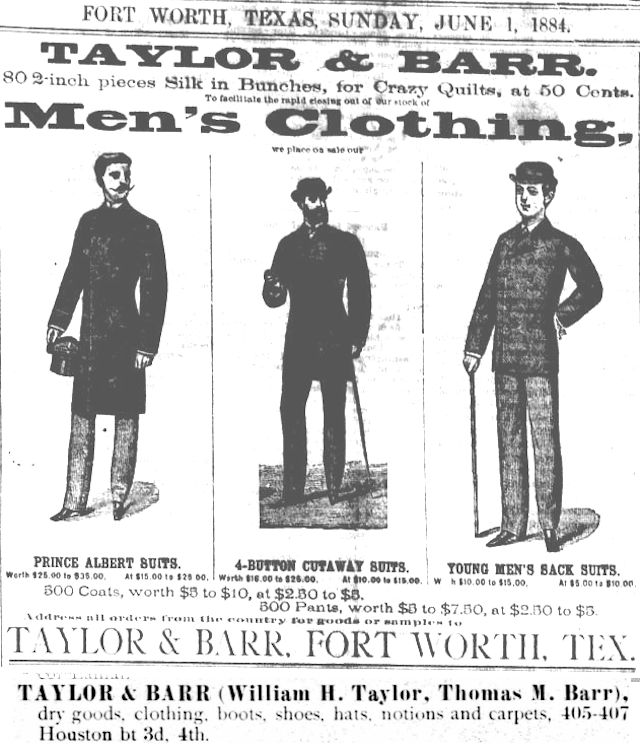

Quanah Parker and Yellow Bear checked into the Pickwick Hotel at Main and 4th streets (at today’s Sundance Square Plaza) but were assigned to “room 78” over Taylor & Barr dry-goods store in the building at 405-407 Houston Street (at today’s Westbrook Building). Perhaps the hotel had no room available in its main building, or perhaps the hotel did not accommodate Native Americans in the main building. But the fact that the room over the dry-goods store was numbered “78” indicates that the room was considered part of the hotel.

Quanah Parker and Yellow Bear checked into the Pickwick Hotel at Main and 4th streets (at today’s Sundance Square Plaza) but were assigned to “room 78” over Taylor & Barr dry-goods store in the building at 405-407 Houston Street (at today’s Westbrook Building). Perhaps the hotel had no room available in its main building, or perhaps the hotel did not accommodate Native Americans in the main building. But the fact that the room over the dry-goods store was numbered “78” indicates that the room was considered part of the hotel.

Fort Worth photographer Augustus R. Mignon took this photo while Quanah Parker and Yellow Bear were in town. Quanah Parker is standing at left. Yellow Bear is seated at left. According to the Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center, medicine man Isa-Tai is seated on the right; the younger Comanche man to the right is thought to be the son of Isa-Tai; and the man next to Parker is thought to be George Briggs. (Photo from DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.)

On the night of December 19—a Saturday—Yellow Bear went to bed about 10 p.m., but Parker went out on the town with George W. Briggs, foreman of the Waggoner ranch. About midnight Parker returned to room 78 and went to bed.

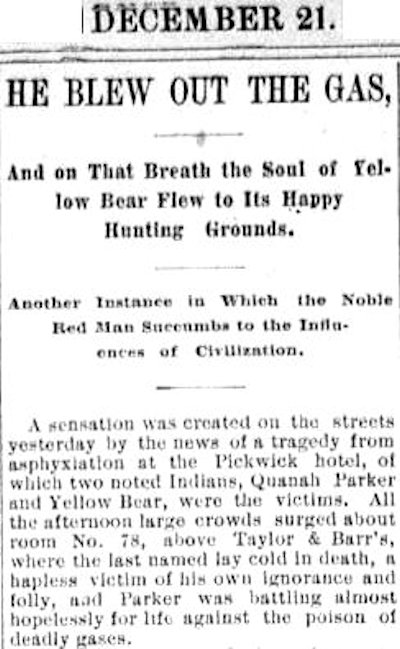

The next morning—December 20—Parker and Yellow Bear did not appear at the hotel for breakfast. Someone reported smelling gas in the Taylor & Barr building. Hotel employees could get no response from room 78. Alarmed, hotel employees forced open the door.

When hotel employees entered the room they found that Yellow Bear was dead; Parker was “battling almost hopelessly for life.” The Gazette wrote: “. . . as the door swung back the rush of the deathly perfume through the aperture told the story. A ghastly spectacle met the eyes of the hotel employees. . . . Yellow Bear was stone dead . . . his companion . . . within but a stone’s throw of eternity.”

Parker later told the Daily Gazette that he had returned to room 78 that night and had found Yellow Bear in bed and the gas lamp extinguished. Parker said he had lit the lamp, undressed, and turned out the lamp. He woke in the night and smelled gas but merely pulled a bedcover over his nose and went back to sleep.

The newspaper quoted Parker: “Me wake up again—me awful sick. Me wake Yellow Bear and say, ‘me sick.’ Yellow Bear say, ‘Me sick, too.’ Me get up and fall about room. Me crazy.”

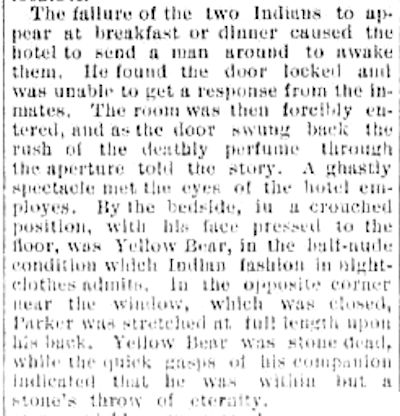

The initial Daily Gazette headline of December 21 had indicated that the theory was that while Parker had been gone Yellow Bear, unfamiliar with the technology, had blown out the flame of the lamp but had not turned off the gas supply to the lamp. However, Parker said that after he had returned to the room he himself had turned off the gas lamp upon retiring. But he apparently had not fully closed the valve. After Parker awoke to the smell of gas and roused Yellow Bear, both men struggled across the floor but lost consciousness. Parker collapsed near a window, which provided him with enough fresh air to survive.

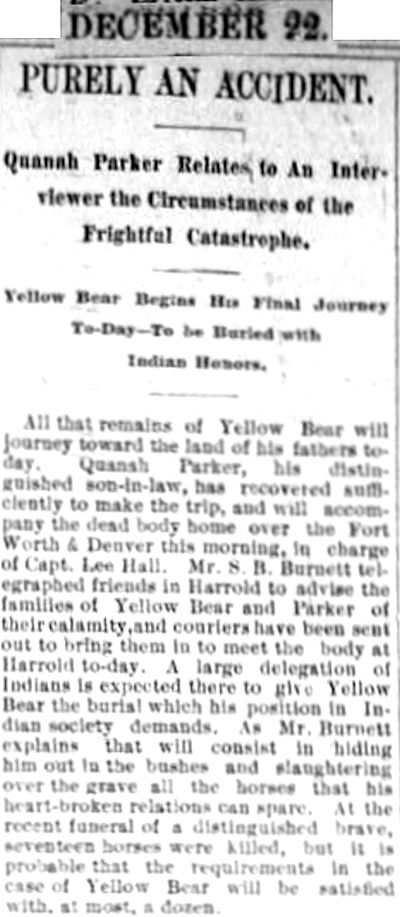

The December 22 Daily Gazette article quoted Burk Burnett’s anticipation of the nature of the burial rites for Yellow Bear.

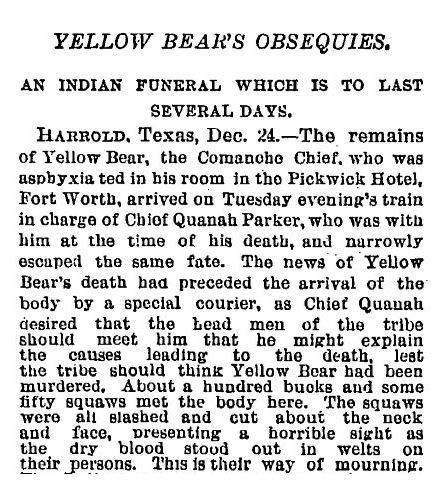

By December 22 Parker was well enough to travel, and he returned by train to Indian Territory with the body of his father-in-law. Harrold (named for cattleman-capitalist E. B. Harrold) is in Wilbarger County near the Red River. It is forty miles southeast of the town of Quanah, which in 1884 had been named for Parker as the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad laid track to Colorado and began to sell lots for the new town. Clip is from the New York Times of December 25.

By December 22 Parker was well enough to travel, and he returned by train to Indian Territory with the body of his father-in-law. Harrold (named for cattleman-capitalist E. B. Harrold) is in Wilbarger County near the Red River. It is forty miles southeast of the town of Quanah, which in 1884 had been named for Parker as the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad laid track to Colorado and began to sell lots for the new town. Clip is from the New York Times of December 25.

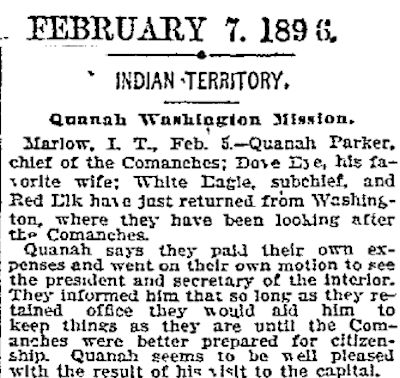

For Quanah Parker there was life after room 78. He represented the Comanches in Washington.

For Quanah Parker there was life after room 78. He represented the Comanches in Washington.

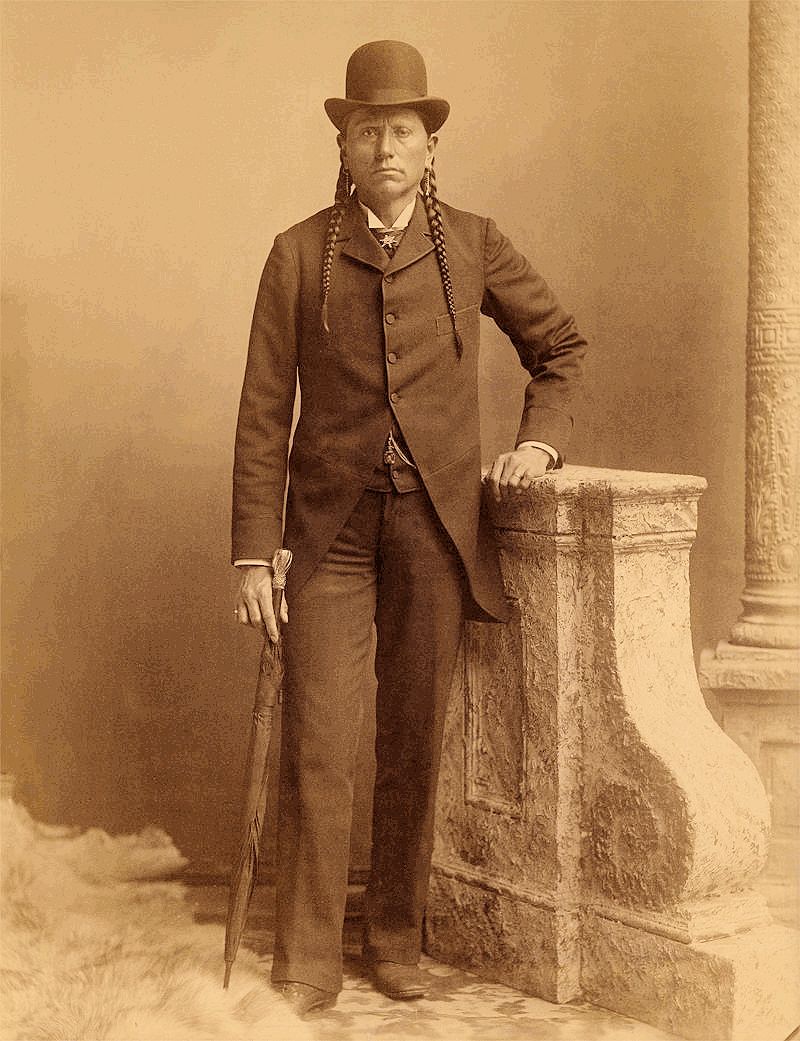

In 1889 Parker posed for photographer Charles Milton Bell. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1889 Parker posed for photographer Charles Milton Bell. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

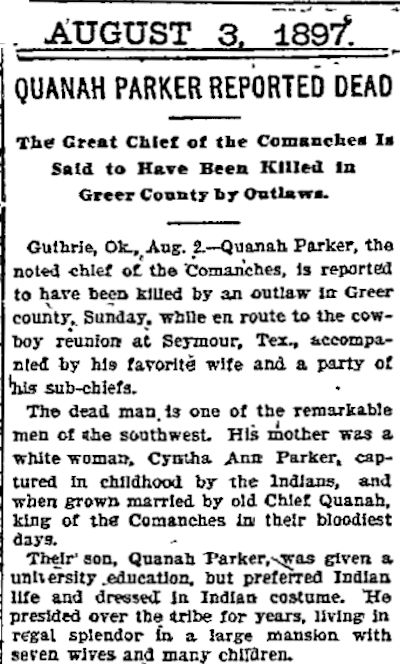

In 1897 Parker was reported dead.

In 1897 Parker was reported dead.

But by 1905 he was feeling much better. In fact, he appeared in the inaugural parade of President Teddy Roosevelt with chiefs Buckskin Charlie of the Ute, American Horse and Hollow Horn Bear of the Sioux, Little Plume of the Blackfeet, and warrior Geronimo of the Apache. A month later when Roosevelt visited Texas and Oklahoma he invited Quanah Parker to participate in a wolf hunt. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

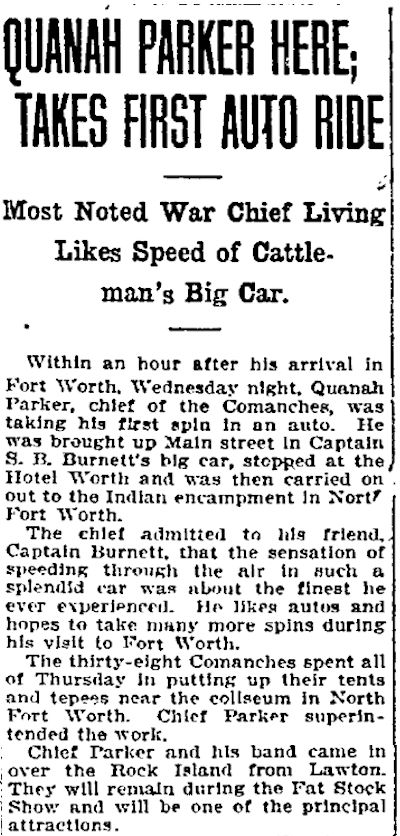

In 1909 Quanah Parker took his first automobile ride in Burk Burnett’s car. Parker and “his band” were in town to perform at the Fat Stock Show, which in those days was held in March on the North Side. Clip is from the March 11 Star-Telegram.

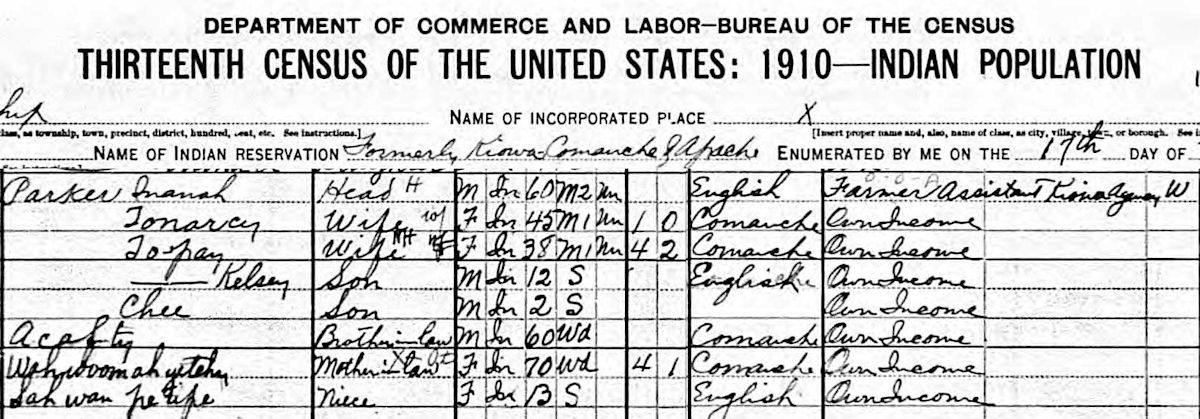

The 1910 census listed Parker, wives Tonarcy and Toe-Pay, and other family members. Parker listed his occupation as farmer and assistant of the Kiowa Indian Agency.

The 1910 census listed Parker, wives Tonarcy and Toe-Pay, and other family members. Parker listed his occupation as farmer and assistant of the Kiowa Indian Agency.

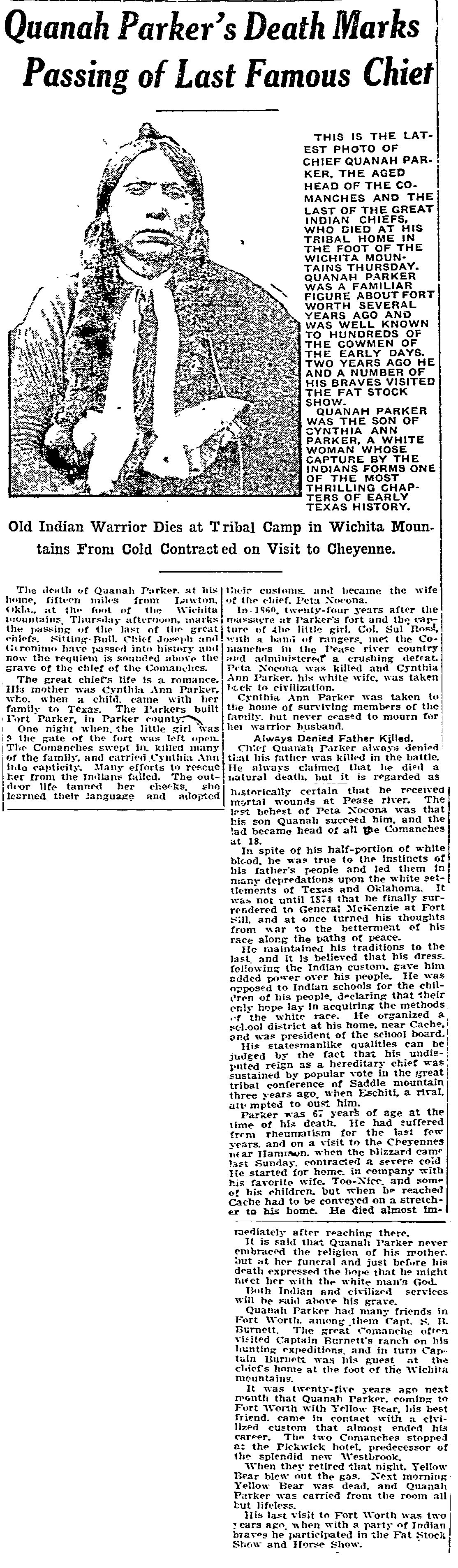

Quanah Parker, who on December 20, 1885 had been, the Daily Gazette wrote, “within but a stone’s throw of eternity” and who was reported killed by outlaws in 1897, died on February 23, 1911. Clip is from the February 24 Star-Telegram.

Quanah Parker, who on December 20, 1885 had been, the Daily Gazette wrote, “within but a stone’s throw of eternity” and who was reported killed by outlaws in 1897, died on February 23, 1911. Clip is from the February 24 Star-Telegram.

Quanah Parker is buried in the post cemetery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The inscription on his monument reads:

Quanah Parker is buried in the post cemetery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The inscription on his monument reads:

Resting Here Until Day Breaks

And Shadows Fall and Darkness

Disappears Is

Quanah Parker

Last Chief of the Comanches

Born 1852

Died Feb. 23, 1911

(Photo from Wikipedia.)

Well done, Mike. This incident was the subject of my first published article in the Chronicles of Oklahoma back in the 1960s!

Thanks, Ron. It’s an incident that continues to stir our imaginations.

Chief Quanah Parker was a very fascinating person, I love reading about him, and his family, and the many sub-chiefs, and the young braves, that surrounded him throughout his illustrious life as a War Chief and as the final great Chief of the Comanche Nation!

Your ID of the group photos are incorrect. They are, standing L-R, Quanah, E.R.Sugg, George W. Fox, Permamsu (aka Comanche Jack); seated,

Sodyteka, Alate (Loud Talker, Kiowa).

Thank you for that information. The caption came from SMU.

I was looking through the Lawrence T. Jones III Texas photography collection (SMU) and found what I assume was the last photo that Yellow Bear had taken before he died on his visit to Fort Worth. This photo was taken at Fort Worth Art gallery 24 Main St. Fort Worth TX.by AR Mignon, Artist.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/jtx/id/1712/rec/13

Very interesting article Mike!

Brian: What a find! I will add that photo to my post with credit to SMU. Thanks for the tip.

I remember seeing a full length movie on maybe TBS or possibly AMC in the 70’s or 80’s I think most likely based on this event. It was at least 20-30 years old when I saw it. Don’t think it was a reenactment, but a hollywood movie.

I’ve always heard this tale as one told of two unnamed Indians and that it happened in the rooms above the Barber’s Bookstore. It’s one of the backstories of the “Barber’s is Haunted” lore.

I had not heard that event tied to the Barber’s building (1910). History is like that party game of “telephone” (“Chinese whispers”), isn’t it? An event occurs, and in the telling and retelling of the event details get changed until eventually the story bears little resemblance to the original. This is one reason why I find old newspapers so interesting: Theirs is the first “voice” on the “telephone.”

Interesting. In “Findagrave,” they also describe the Southern Arapaho Yellow Bear as Parker’s father-in-law. No explanation for the death date discrepancy. The more I looked, the more confused I got so you were wise to tread lightly.

“The more I looked, the more confused I got.” Happens all the time. Conflicting info and lack of info are maddeningly common when the main sources are decades-old newspaper accounts. For example, I saw Yellow Bear described as Parker’s uncle, father-in-law, and “good friend.” These are not mutually exclusive, but . . .

Was Yellow Bear Comanche or, as his gravestone states, Southern Arapaho?

In my research I saw him described as “Comanche subchief,” “full-blooded Comanche, “associate chief” of Quanah Parker. But I had come across a photo of the “Arapaho” Yellow Bear but was afraid to use it because of the apparent discrepancy in affiliation and that “1887” (not 1885) on the tombstone. I also found a photo of the “Arapaho” Yellow Bear apparently dated 1899. There was also an Oglala chief with the same name. In my text I referred to the victim as merely “Chief.”