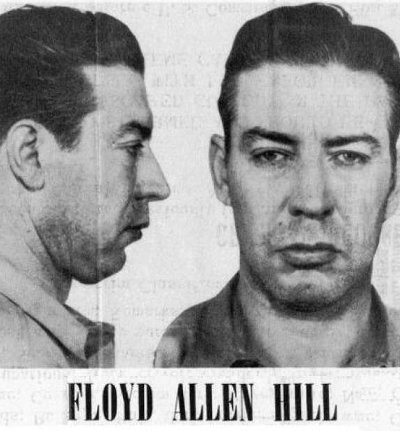

When he was born he was poured into a mold that has misshapen many a young man: He dropped out of school, watched his parents divorce, broke the law as a teenager, and went to prison, where he received the kind of education that is not available in public schools. By the time he graduated from the university of Alcatraz he was fully trained for a career in crime. By the time his life of crime ended he would be known as the “gray scourge of the Southwest.”

Floyd Allen Hill was born in Texas in 1912. He quit school after the third grade before he could read or write. He later recalled, “I got kicked out of my home by a stepfather when I was ten years old. I hung out with older men and learned to be a criminal from them.”

Floyd Allen Hill was born in Texas in 1912. He quit school after the third grade before he could read or write. He later recalled, “I got kicked out of my home by a stepfather when I was ten years old. I hung out with older men and learned to be a criminal from them.”

His first conviction came at age eighteen. He went to prison, where he continued to meet older men who served as teachers.

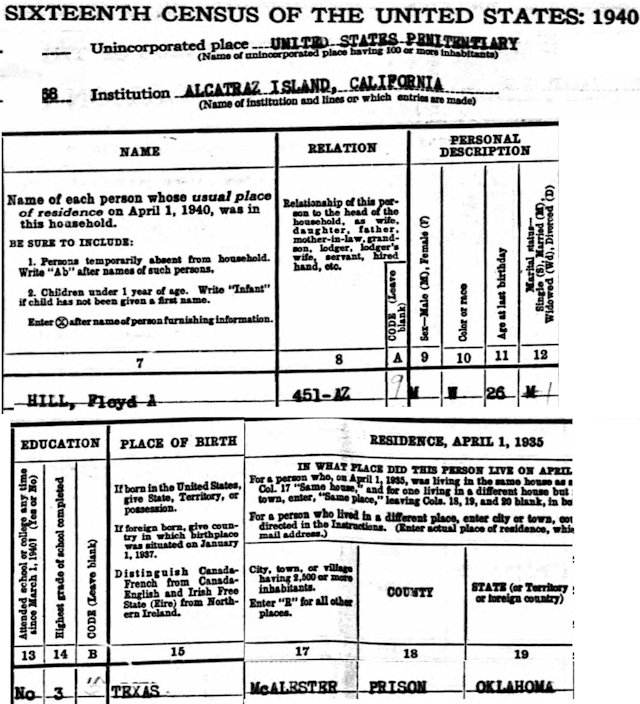

By 1935 Hill was enrolled at Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. In 1938 Hill was sentenced to Alcatraz federal prison for post office burglary.

By 1935 Hill was enrolled at Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. In 1938 Hill was sentenced to Alcatraz federal prison for post office burglary.

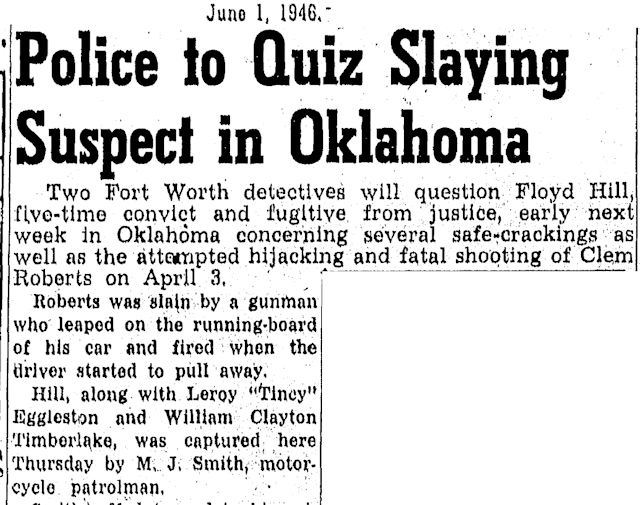

Fast-forward to 1946. The Star-Telegram described Hill as a “five-time convict and fugitive from justice” after Hill was suspected of several safecrackings and the murder of an Oklahoma man during a hijack attempt. Hill, along with fellow Fort Worth gangland overachiever Leroy “Tincy” Eggleston, was captured after a police officer spotted the pair on Jacksboro Highway. Hill and Eggleston were in possession of marijuana and burglary tools.

Fast-forward to 1946. The Star-Telegram described Hill as a “five-time convict and fugitive from justice” after Hill was suspected of several safecrackings and the murder of an Oklahoma man during a hijack attempt. Hill, along with fellow Fort Worth gangland overachiever Leroy “Tincy” Eggleston, was captured after a police officer spotted the pair on Jacksboro Highway. Hill and Eggleston were in possession of marijuana and burglary tools.

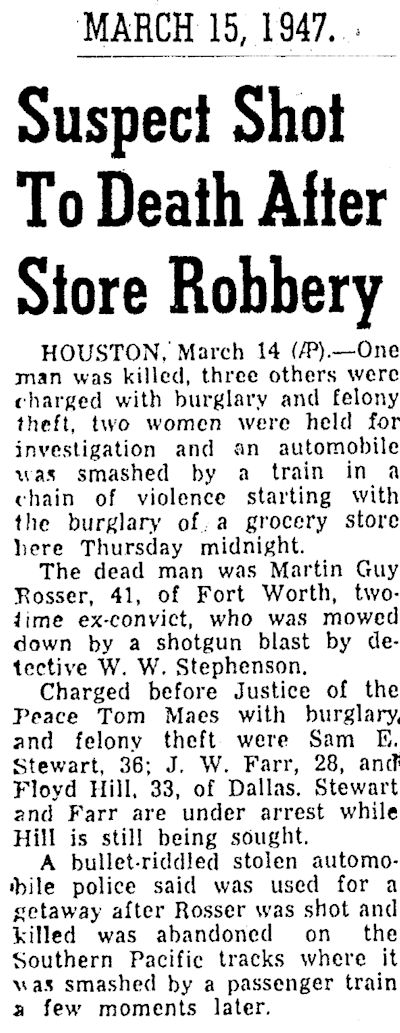

The next year Hill was in Houston, where the burglary of a grocery store led to a shootout with a police detective that left one burglar dead, two burglars in jail charged with felony theft, two women being held for investigation, Hill on the lam, and the stolen getaway car riddled with bullets and then smashed by a passenger train after the burglars abandoned the car on Southern Pacific railroad tracks.

The next year Hill was in Houston, where the burglary of a grocery store led to a shootout with a police detective that left one burglar dead, two burglars in jail charged with felony theft, two women being held for investigation, Hill on the lam, and the stolen getaway car riddled with bullets and then smashed by a passenger train after the burglars abandoned the car on Southern Pacific railroad tracks.

In 1951 Hill reenrolled at Alcatraz U for postgraduate study, this time sentenced for transporting firearms and autos in interstate commerce.

Then came 1952. Hill was back in Fort Worth, granted a conditional parole for good behavior.

It was time for the graduate student of crime to write his dissertation.

Some back story: Among the residents of Mexico City’s cultural melting pot in 1952 were two Cuban exiles: Candido de la Torre and Manuel Madareaga. De la Torre had been a Havana city councilman. Madareaga was “retired.” The two men had left Cuba after Fulgencio Batista, with military backing, had overthrown President Carlos Prio Socarras in March of that year. The two men had been “close” to Socarras.

While in exile De la Torre and Madareaga devised a scheme. And for that scheme they needed Jose Duarte. Duarte was important to the scheme for two reasons: (1) He still lived in Cuba and (2) he was a weapons expert.

The three men were scheming to buy weapons to arm rebels to overthrow Batista.

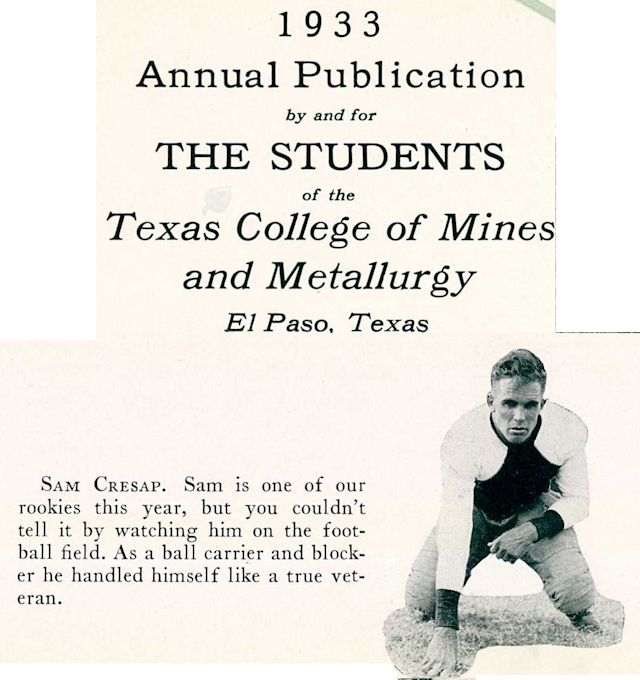

Enter Sam Brown Cresap, a former college football player from El Paso who in 1952 was a Fort Worth car salesman.

Enter Sam Brown Cresap, a former college football player from El Paso who in 1952 was a Fort Worth car salesman.

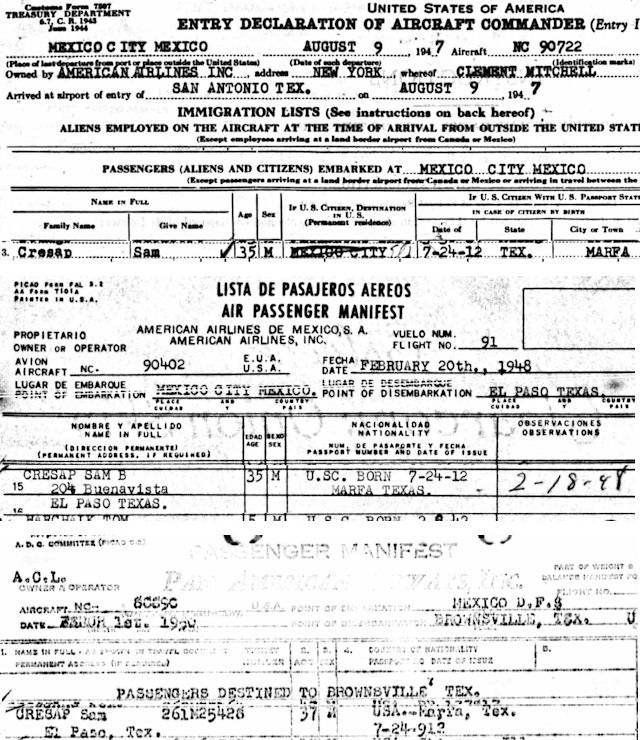

Cresap visited Mexico often, staying at the Geneve Hotel in Mexico City. While in Mexico City in 1952 Cresap became acquainted with Madareaga. Then Cresap learned that Madareaga was seeking guns. A lot of guns. Sensing a sucker, Cresap devised a con.

Cresap visited Mexico often, staying at the Geneve Hotel in Mexico City. While in Mexico City in 1952 Cresap became acquainted with Madareaga. Then Cresap learned that Madareaga was seeking guns. A lot of guns. Sensing a sucker, Cresap devised a con.

Madareaga later told authorities: Cresap “said he might get me in contact with a man who could provide the arms. But he told me I would have to come to Texas.”

And Madareaga would need to take money to Texas. A lot of money.

Toward that end, on September 23 De la Torre and Madareaga arrived in Fort Worth from Mexico in a late-model Cadillac. On October 1 they made an agreement with Sanford Webb car dealership to buy a new Buick. Also on October 1 De la Torre flew to New York City. In a room of the exclusive Carlisle Hotel on 76th Street on the upper East Side of Manhattan, ex-President Carlos Prio Socarras gave De la Torre a valise stuffed with $50, $100, and $500 bills. (The U.S. Treasury Department would discontinue the $500 bill in 1969.)

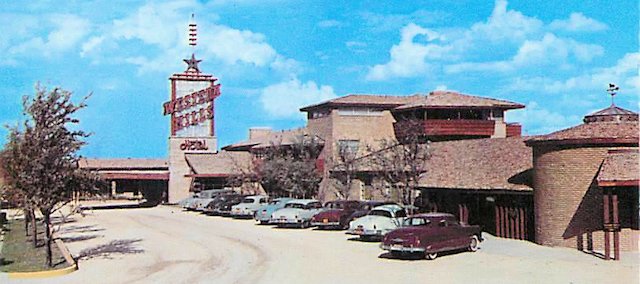

De la Torre returned to Texas on either October 1 or October 2. When he and the money landed at Love Field in Dallas, they were met by Cresap and a second conman. Cresap then drove De la Torre and the money to Fort Worth, where Madareaga and Duarte were waiting in a cabana at the Western Hills Hotel on Camp Bowie Boulevard.

About 8 p.m. on the night of October 2 De la Torre, Madareaga, and Duarte were in the cabana when Cresap returned with an American called “Johnny.” About 10 p.m. weapons expert Duarte and Cresap left and drove to Dallas, where, Madreaga later told authorities, “we were to contact a man who could tell me about some arms he might have for sale.”

Johnny stayed behind with De la Torre and Madareaga. Johnny dumped the contents of the valise onto the bed and counted the money: $248,000 ($2.2 million today). He then suggested that the three play cards while they waited for Duarte and Cresap to return.

Madareaga later told authorities that he had brought the money only to display it to Cresap. Madareaga said he had expected the guns to be delivered to the Cubans at a later date and possibly out of the country.

About 3:30 a.m. Johnny told the two Cubans he heard a noise outside the door of the cabana. He went to the door to investigate. Madareaga later told authorities: Johnny “turned and waved a pistol as a man wearing a handkerchief and carrying a submachine gun came into the room.”

Johnny and the masked man forced the two Cubans to lie on the floor and bound their wrists and ankles with wire.

“If you report this, I’ll come back and take care of you,” the masked man with the Tommy gun told the two Cubans.

Then the two robbers and the $248,000 walked out the door.

Madareaga was able to knock the room telephone to the floor and speak into it to the hotel operator.

“Banditos!” he muttered. (The robbers had counted on the Cubans not reporting the armed robbery to police because buying U.S. arms for use in a revolution was illegal.)

When police arrived at the cabana, Madareaga was sitting on the floor making a phone call to New York City. He spoke in Spanish, but a police officer heard the words “el presidente.”

Meanwhile in Dallas, Duarte later told authorities, Cresap received a phone call instructing him and Duarte to go to Gainesville to meet the supposed gunrunner. But after a considerable wait, Duarte later said, Cresap concluded that the gunrunner was not going to show. Cresap and Duarte then ate a meal in Gainesville. Then, Duarte later said, Cresap drove the pair at a “leisurely” pace back to the Western Hills Hotel. When they arrived two police cars were parked near the Cubans’ cabana. When Duarte started to get out of the car to go to the cabana, Cresap held Duarte’s arm and told him not to go. Duarte went anyway. Soon after, Cresap was arrested at the scene.

The robbery was the lead story on page 1 on October 4, 1952.

The robbery was the lead story on page 1 on October 4, 1952.

The con game was played by four men:

The con game was played by four men:

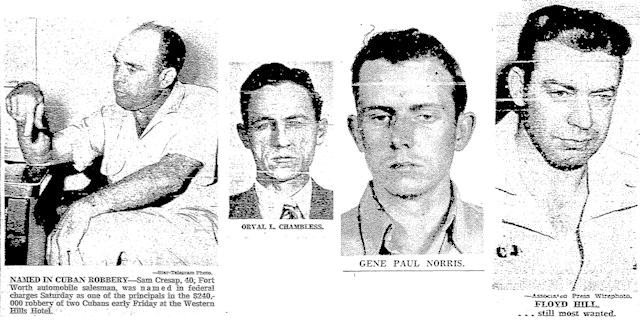

Sam Brown Cresap (the initial contact with the Cubans). Cresap, a Fort Worth car dealer, was the only one of the four men with no criminal record.

Orville Lindsey Chambless (he met in Dallas with the Cubans, possibly on the day Cresap met De la Torre at Love Field). Chambless, an ex-convict, was an Oklahoma bootlegger with a leg up: Rather than deliver his product in a souped-up car he used a private airplane.

Gene Paul Norris (“Johnny”). Norris was a local contract killer. He also robbed gamblers and others whose source of income rendered them hesitant to report a robbery to police. Before the Western Hills robbery Norris already had a record of twenty-five arrests and six convictions.

Floyd Allen Hill (the masked man with the Tommy gun). Police described Norris and Hill as “cronies.” Both men would make the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

After Manuel Madareaga muttered “Banditos!” into the telephone at the Western Hills Hotel, police acted quickly. Sam Brown Cresap, of course, was arrested at the scene of the robbery on October 3.

After Manuel Madareaga muttered “Banditos!” into the telephone at the Western Hills Hotel, police acted quickly. Sam Brown Cresap, of course, was arrested at the scene of the robbery on October 3.

When police showed the Cubans a “rogues’ gallery” mugbook, the Cubans identified Chambless and Norris. Police suspected that Chambless or Norris took at least some of the robbery money to Oklahoma. Chambless was arrested October 4 in Oklahoma City. Charmless implicated Hill and Norris in the robbery. Norris was arrested October 6 in Duncan, Oklahoma.

That left only Floyd Allen Hill at large.

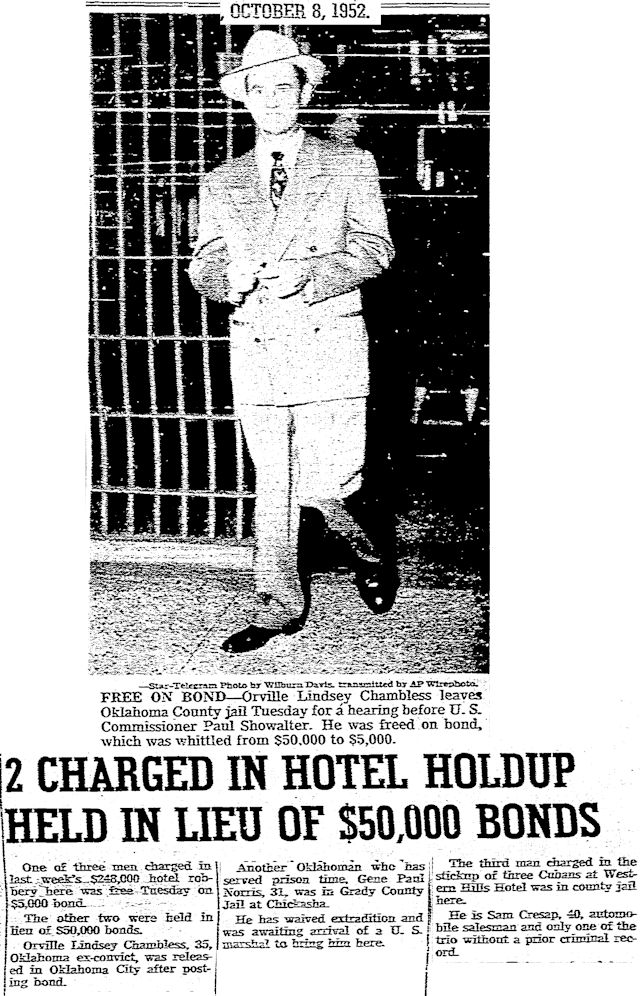

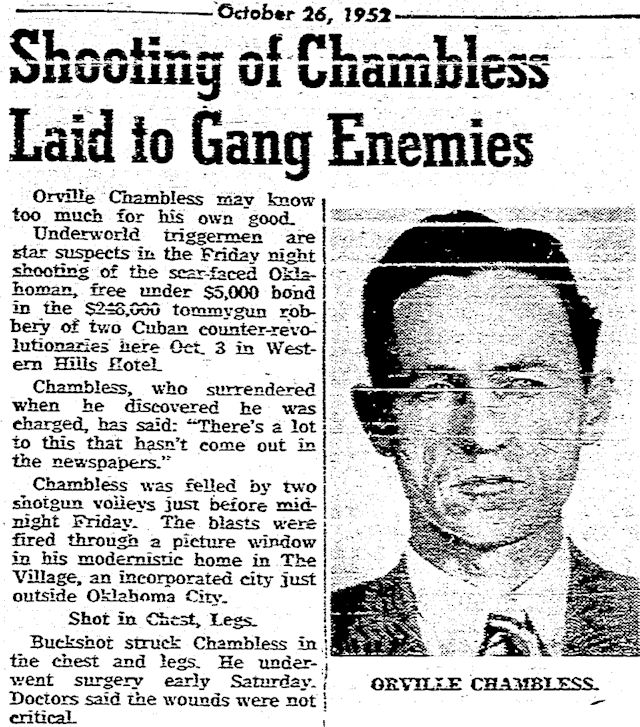

Chambless was freed on bond on October 7. Later that month he was wounded by two twelve-gauge shotgun blasts fired through a window of his home in Oklahoma. Police suspected underworld triggermen whose motive might have been (1) to settle an old score, (2) to settle with Chambless for implicating Hill and Norris in the Western Hills Hotel robbery, or (3) to keep Chambless from talking further about the robbery.

Chambless was freed on bond on October 7. Later that month he was wounded by two twelve-gauge shotgun blasts fired through a window of his home in Oklahoma. Police suspected underworld triggermen whose motive might have been (1) to settle an old score, (2) to settle with Chambless for implicating Hill and Norris in the Western Hills Hotel robbery, or (3) to keep Chambless from talking further about the robbery.

A few days later federal authorities moved Gene Paul Norris from Tarrant County jail to an undisclosed location after guards learned from the jail grapevine that “six men from the outside” were coming to free a prisoner.

Floyd Hill, the only member of the robbery gang still at large, was arrested November 3.

Floyd Hill, the only member of the robbery gang still at large, was arrested November 3.

And Hill’s arrest came with a bonus. Police had spotted Hill’s wife Juanita in a car and pulled her over. In her purse they found a postcard addressed to “Gene Williams” at 2712 Skyline Drive, east of Jacksboro Highway. Suspecting that the house was Hill’s hideout, police searched the premises. They did not find Hill, but they did find nitroglycerin, a fuse, and blasting caps.

An FBI agent and Fort Worth deputy Police Chief Cato Hightower and another police officer hid in the house and waited.

Meanwhile police had learned—most likely from Hill’s wife—where Hill had hidden his share of the robbery money. While police waited at the Skyline Drive house, that night other officers went to a pasture five miles east of Azle. After forty-five minutes of digging within a specific area they found Hill’s hidey-hole.

Hill had buried a paraffin-sealed one-gallon Thermos bottle containing $128,000 and a glass jar containing $4,250 in bonds that he had taken in a robbery in Kilgore. Fort Worth police detective A. C. Howerton (brother of Police Chief Roland Howerton), who in 1933 had helped break the O. D. Stevens mail car robbery case, was among the officers who found the buried treasure. The officers then staked out the hidey-hole.

Hill had buried a paraffin-sealed one-gallon Thermos bottle containing $128,000 and a glass jar containing $4,250 in bonds that he had taken in a robbery in Kilgore. Fort Worth police detective A. C. Howerton (brother of Police Chief Roland Howerton), who in 1933 had helped break the O. D. Stevens mail car robbery case, was among the officers who found the buried treasure. The officers then staked out the hidey-hole.

Meanwhile Hill went to the Skyline Drive house. Through a window he saw Hightower in the house and figured he’d better get to his money before the police did.

He was too late. When he showed up at the hidey-hole and got out of his car holding a garden hoe, police officers stepped out of the darkness, their shotguns trained on him.

When Floyd Hill showed up armed with only a garden hoe, his old teachers at Alcatraz U probably would have given him a failing grade, but under the circumstances they might have raised that grade to a C when he and his hoe wisely offered no resistance to the shotguns.

The Gray Scourge of the Southwest (Part 2): A “High-Class” Hoodlum

Did they ever recover the tommy gun?

Ghost Writer, I suspect the gun was recovered, but I have found no reportage of that. Hill confessed to his role in the robbery. He said he pleaded guilty so he could get back to prison for medical treatment.