For twenty-eight years it hunkered in a corner of the Texas & Pacific reservation covered in coal soot and anonymity: an unadorned two-room wooden building.

Then, one day in 1931, a wrecking crew arrived.

The Texas & Pacific reservation was a sprawling maze of tracks and trains and buildings at the south end of downtown bounded by Lancaster Avenue and Vickery Boulevard and by Lamar and Grove streets. The reservation was undergoing tremendous change in 1931. T&P had already built—in 1928—a new railyard (which today is Union Pacific’s Davidson yard) off Stove Foundry Road 2.6 miles to the southwest. The new T&P yard was named in honor of T&P president John L. Lancaster.

Elsewhere on the reservation in 1931 T&P was replacing its passenger depot and its freight depot with new depots along Lancaster Avenue (also named for the T&P president). Buildings and tracks were being removed. Land was being repurposed. In addition, the railroad and the city were building underpasses for vehicular traffic on Main, Jennings, and Henderson streets. The Jennings Avenue underpass would replace a wooden viaduct over the T&P tracks.

But nothing that ambitious challenged members of the wrecking crew that day in 1931 as they gathered before the old wooden building in the corner of the reservation. Their tools and their job were simple: Using crowbars, tear down the old section house. Section houses had two functions in railroading: to house gandy dancers—workers who maintained a section of track—or to store the equipment used by such workers. Since 1903 the little building near the south end of the Jennings Avenue viaduct had been used to store equipment.

But the section house contained more than sledge hammers, cold chisels, tie tongs, and the like. The section house contained a secret that hinted at a former life and a Fort Worth first.

And the wrecking crew was about to uncover part of that secret.

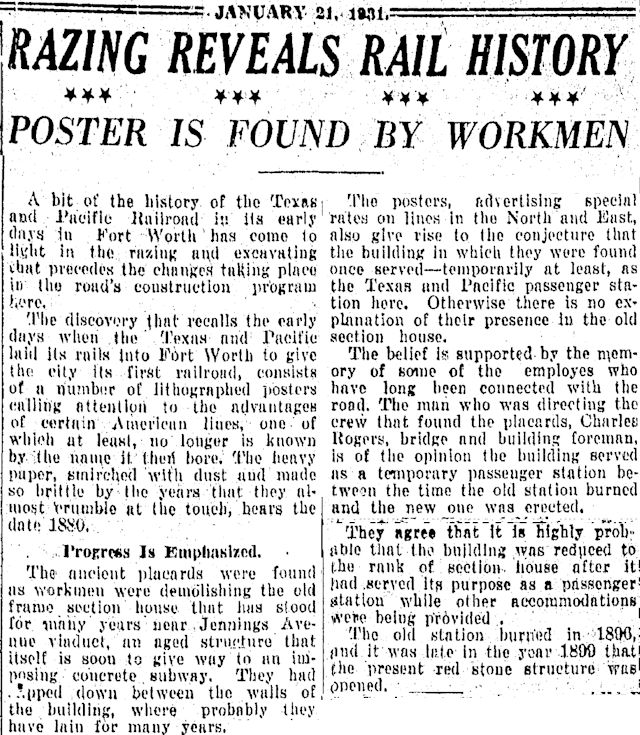

As the crew was tearing down the building, the Star-Telegram reported in 1931, a worker found three lithographed posters inside a wall. The posters were “brittle” and “smirched with dust.”

As the crew was tearing down the building, the Star-Telegram reported in 1931, a worker found three lithographed posters inside a wall. The posters were “brittle” and “smirched with dust.”

Dated 1880, the posters promoted passenger travel on three railroads: the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern, the Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific, and the Illinois Central.

The man who was directing the wrecking crew—T&P bridge and building foreman Charles Rogers—upon seeing the 1880 posters theorized that the old building had been used temporarily as the Texas & Pacific passenger depot between the years 1896, when fire destroyed the passenger depot built in 1882, and 1899, when the replacement depot opened. T&P oldtimers confirmed this theory.

Rogers was “warm,” but the full story was even hotter: The old section house being torn down in 1931 had been built as Fort Worth’s first passenger depot. (First clue: Posters dating from 1880 are more likely to be found in a building that was used as a passenger depot in 1880, not 1896-1899.)

Now let’s shift this train of events into reverse and back up to 1876.

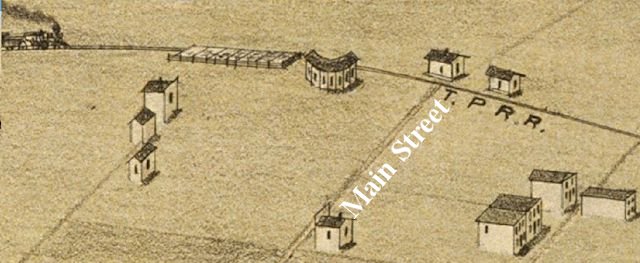

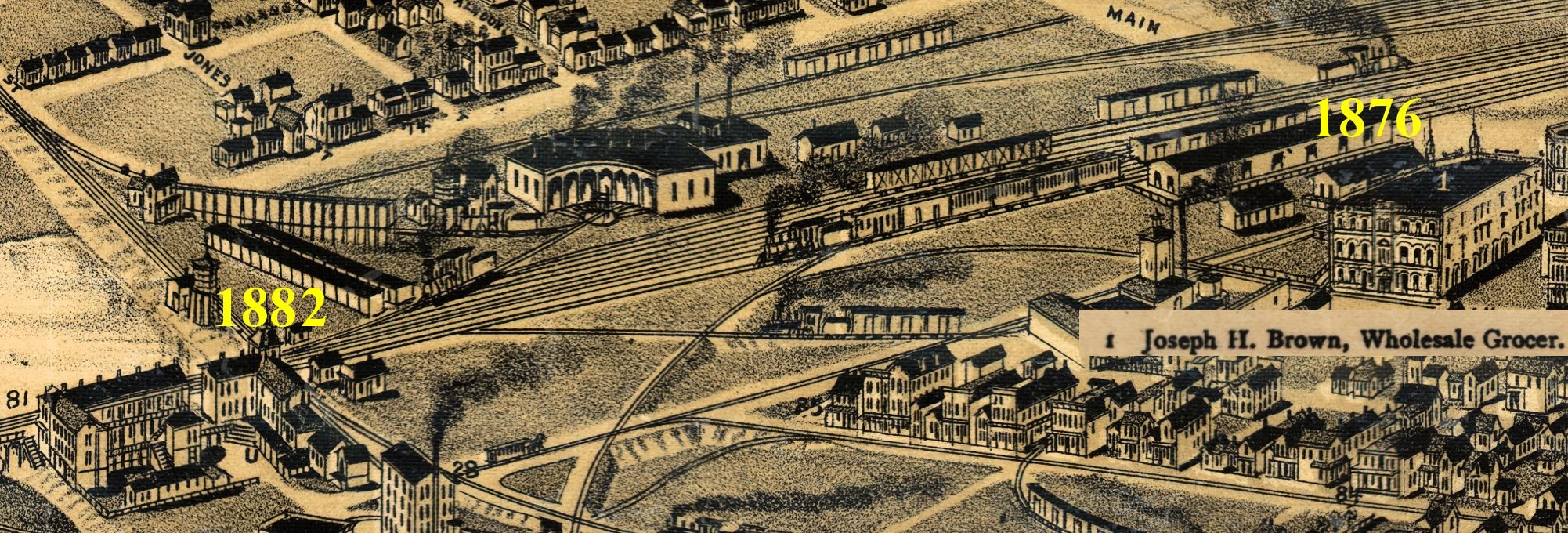

On September 2, 1876, just six weeks after the first T&P train shook, rattled, and rolled into town, the city and the railroad dedicated the new passenger depot, located in the sparsely populated south end of town where the T&P track met Main Street a mile below the courthouse. The depot was a modest one-story, two-room wooden building with a gabled roof and a coat of gray paint. This 1876 Morse bird’s-eye-view map detail shows a train approaching cattle pens, a roundhouse, and two buildings at the junction of the track and Main Street. Presumably one of those two buildings is the passenger depot. The other building may be the freight depot.

On September 2, 1876, just six weeks after the first T&P train shook, rattled, and rolled into town, the city and the railroad dedicated the new passenger depot, located in the sparsely populated south end of town where the T&P track met Main Street a mile below the courthouse. The depot was a modest one-story, two-room wooden building with a gabled roof and a coat of gray paint. This 1876 Morse bird’s-eye-view map detail shows a train approaching cattle pens, a roundhouse, and two buildings at the junction of the track and Main Street. Presumably one of those two buildings is the passenger depot. The other building may be the freight depot.

At the depot’s dedication ceremony on September 2 Captain B. B. Paddock made a brief speech and presented a gold-headed cane to L. J. Swingley, the new station agent. Paddock, Cowtown’s head cheerleader and editor of the Fort Worth Democrat, in 1873 had predicted with his tarantula map that Fort Worth would become a major railroad hub. Now, after three years of delay, Paddock saw in that first train and that first depot his vision beginning to be rendered in iron and wood. Also on September 2 Paddock was given the honor of buying the first ticket sold in the new depot. He bought a ticket to Dallas “of his own free will and volition,” the Fort Worth Telegram recalled in 1903 with some chagrin. In truth, Paddock didn’t have many choices: In 1876 the new Fort Worth depot was the western terminus of the only railroad in town.

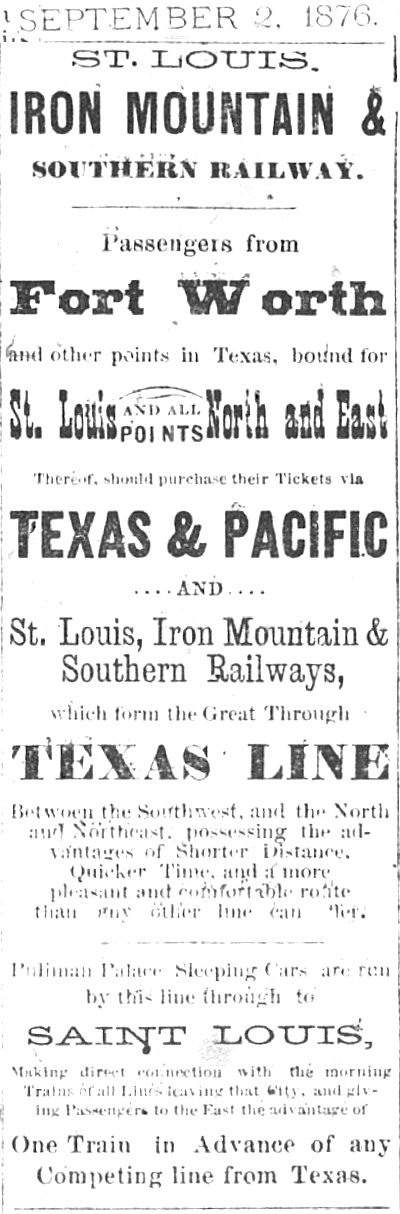

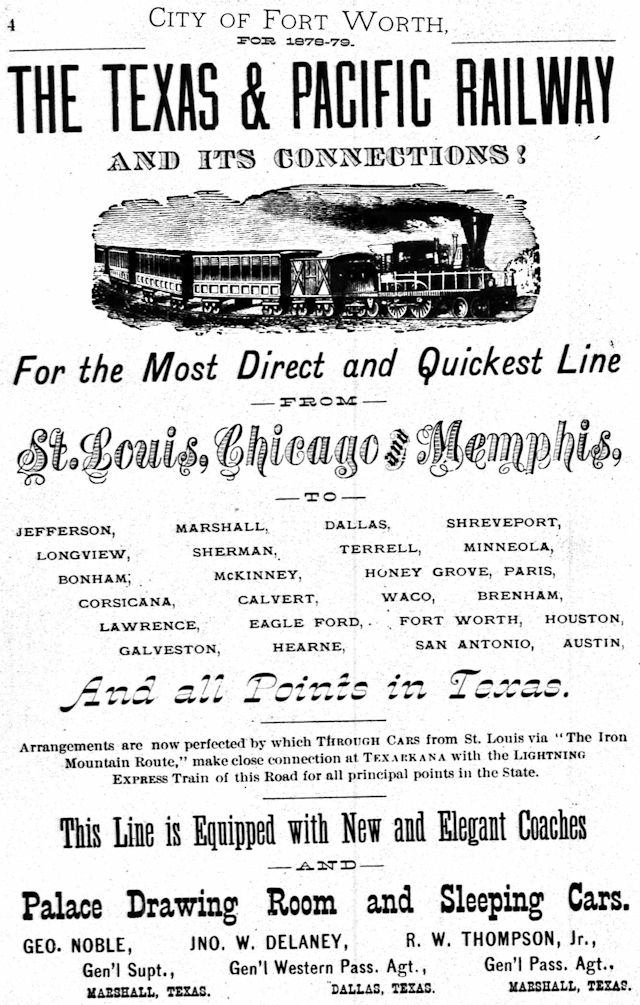

Nonetheless, the little depot was Fort Worth’s first iron gateway to the globe. In September 1876 people could walk into the depot, buy a ticket, and travel east not just to Dallas but to Texarkana, to Shreveport. And Fort Worth travelers were not confined to just the T&P line. In some cities served by the T&P, passengers could connect to other railroads and travel still farther from home. One of the first railroads to advertise its T&P connections in a Fort Worth newspaper was the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern, which ran between St. Louis and Texarkana. In Texarkana Fort Worth passengers of the T&P could connect to “St. Louis and all points north and east.”

Nonetheless, the little depot was Fort Worth’s first iron gateway to the globe. In September 1876 people could walk into the depot, buy a ticket, and travel east not just to Dallas but to Texarkana, to Shreveport. And Fort Worth travelers were not confined to just the T&P line. In some cities served by the T&P, passengers could connect to other railroads and travel still farther from home. One of the first railroads to advertise its T&P connections in a Fort Worth newspaper was the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern, which ran between St. Louis and Texarkana. In Texarkana Fort Worth passengers of the T&P could connect to “St. Louis and all points north and east.”

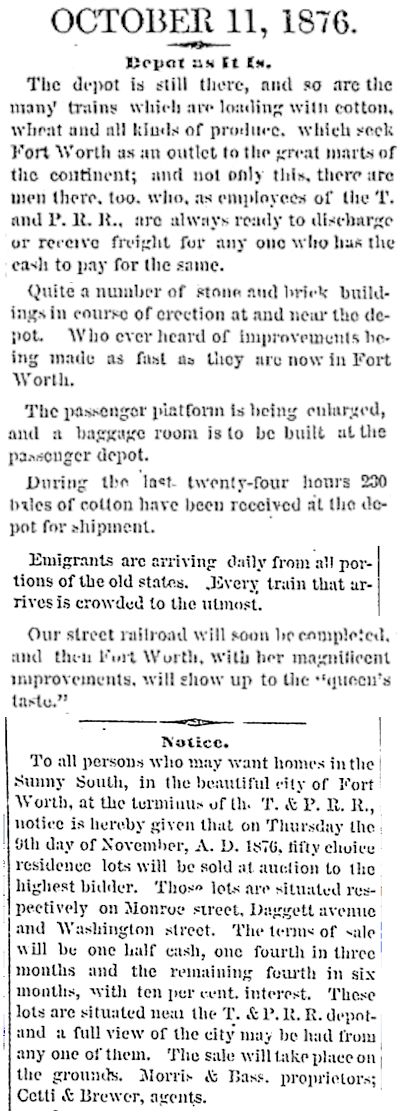

The railroad—via the people and freight coming and going through its passenger and freight depots—transformed Fort Worth. Suddenly the hotels were full, and more were being built. People were sleeping in tents because of a housing shortage. New businesses were opening. Each edition of the Daily Fort Worth Standard crowed about the boom. Clips from October 11, 1876 show that the new passenger depot was already being enlarged as immigrants arrived daily. The freight depot was shipping and receiving cotton, wheat, “and all kinds of produce.” Ice, beer, fresh produce and seafood, the mail—all could be shipped in on the railroad. New buildings of stone and brick were being built, a streetcar track was being laid on Main Street between the courthouse and the new depots, and town lots were being sold.

The railroad—via the people and freight coming and going through its passenger and freight depots—transformed Fort Worth. Suddenly the hotels were full, and more were being built. People were sleeping in tents because of a housing shortage. New businesses were opening. Each edition of the Daily Fort Worth Standard crowed about the boom. Clips from October 11, 1876 show that the new passenger depot was already being enlarged as immigrants arrived daily. The freight depot was shipping and receiving cotton, wheat, “and all kinds of produce.” Ice, beer, fresh produce and seafood, the mail—all could be shipped in on the railroad. New buildings of stone and brick were being built, a streetcar track was being laid on Main Street between the courthouse and the new depots, and town lots were being sold.

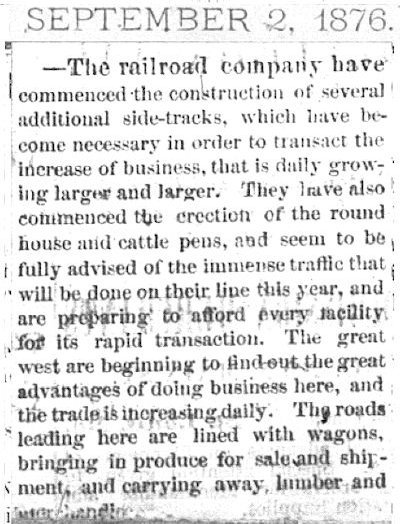

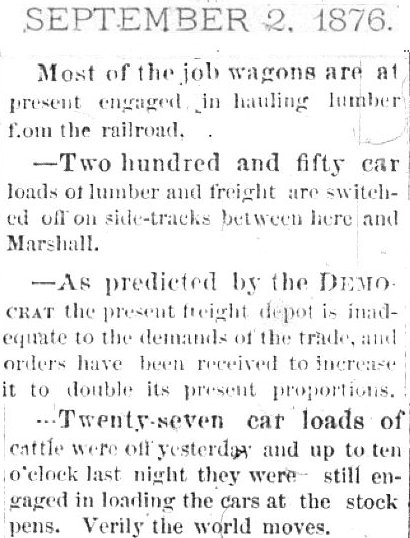

Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat, like the Daily Fort Worth Standard, crowed about the railroad, peppering its local news page with updates: Sidings were being laid, cattle pens and a roundhouse were being built. Wagons were hauling, cattle and lumber were being shipped, the freight depot was to be enlarged.

Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat, like the Daily Fort Worth Standard, crowed about the railroad, peppering its local news page with updates: Sidings were being laid, cattle pens and a roundhouse were being built. Wagons were hauling, cattle and lumber were being shipped, the freight depot was to be enlarged.

“Verily the world moves.”

(Newspapers of the era devoted much more space to national news than to local news, perhaps because readers could get national news only from a newspaper, whereas they could get local news from word of mouth. Case in point: The Democrat’s story about the arrival of the first train on July 19—arguably the most important event in Fort Worth history to that point—was only nine column inches on an inside page. Today such an event would merit a special edition.)

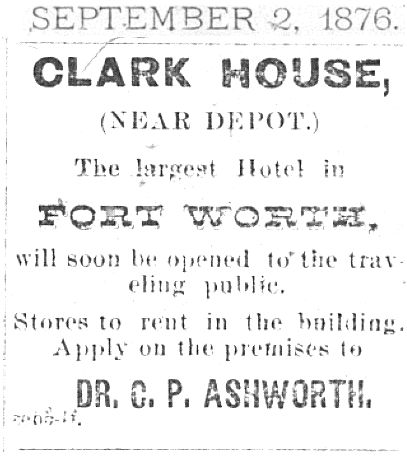

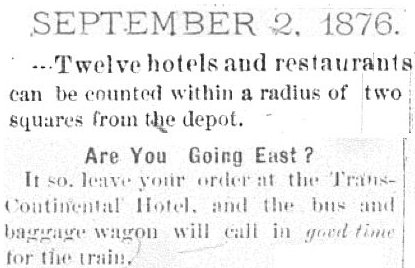

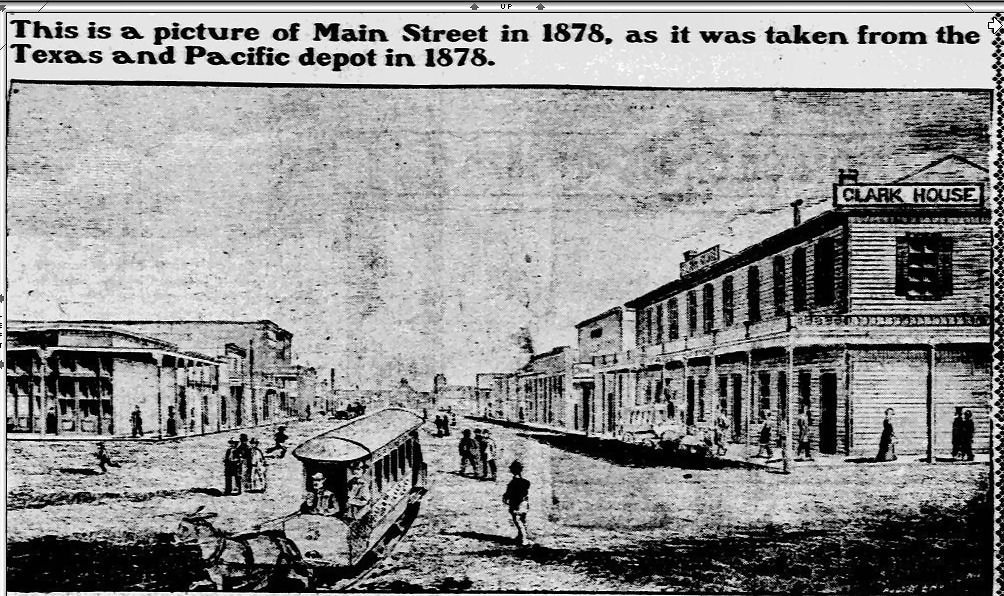

An ad on September 2 announced that the Clark House hotel, located across today’s Lancaster Avenue from the passenger depot, would open soon. The Democrat reported that twelve hotels and restaurants “can be counted within a radius of two squares from the depot.”

An ad on September 2 announced that the Clark House hotel, located across today’s Lancaster Avenue from the passenger depot, would open soon. The Democrat reported that twelve hotels and restaurants “can be counted within a radius of two squares from the depot.”

The Trans-Continental Hotel was on the courthouse square a mile away but advertised transportation to the passenger depot for travelers “going east.” In those days a bus (short for omnibus) was a horse-drawn passenger vehicle.

Yes, the arrival of the railroad was an economic bonanza for Cowtown. Fort Worth’s economy had suffered from 1873 to 1876, in general because of the financial panic of 1873 and in particular because the panic had delayed the arrival of the railroad for three years. But the arrival of the railroad also was a psychological bonanza for Cowtown. During that three-year delay, as Fort Worth had languished, Dallas, with two railroads to Fort Worth’s none, had prospered. Fort Worth, which felt it should be and one day would be the equal of Dallas, developed an inferiority complex as an intercity rivalry grew, fought mostly between the towns’ newspapers.

Yes, the arrival of the railroad was an economic bonanza for Cowtown. Fort Worth’s economy had suffered from 1873 to 1876, in general because of the financial panic of 1873 and in particular because the panic had delayed the arrival of the railroad for three years. But the arrival of the railroad also was a psychological bonanza for Cowtown. During that three-year delay, as Fort Worth had languished, Dallas, with two railroads to Fort Worth’s none, had prospered. Fort Worth, which felt it should be and one day would be the equal of Dallas, developed an inferiority complex as an intercity rivalry grew, fought mostly between the towns’ newspapers.

Dallas had delivered an especially stinging barb on February 2, 1875. Robert E. Cowart, a Dallas lawyer who had formerly lived in Fort Worth, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom and wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will” and even had napped unmolested on one of the town’s main streets. After residents discovered panther tracks on a downtown street, Cowart wrote, residents convened a meeting, and a Parson Fitzgerald drove a stake into the ground to mark “whar the pant[h]er had laid down.”

But Fort Worth twisted the barb into a benediction. Fort Worth embraced the appellation. Fort Worth newspapers and advertisers began to refer to the town as “Pantherville” and “where the panther laid down.” Newspapers elsewhere followed suit. The town’s baseball team would be named the “Panthers.”

Thus, on July 19, 1876, after the future finally rolled into Fort Worth three years late, the Fort Worth Democrat celebrated by proclaiming that the “shrill scream” of the whistle of the steam engine roused “the ‘pant[h]er’ from his lair.”

On September 2, the day the passenger depot was dedicated, Paddock’s Democrat looked back on those three long years and explained the origin of the expression “where the panther laid down.” Excerpts from this eye-squinting clip: “In the winter of 1874-5 Fort Worth was about as dull as towns of its size ever get to be,” the Democrat admitted. “One extension after another granted to the railroad company [to lay the T&P track from Dallas County to Fort Worth], together with the reverses sustained by the panic of the fall of 1873, from which the city had not fully recovered, tended to produce a dearth that threatened at one time to almost depopulate the town.”

But meetings of “faithful, confident, public-spirited citizens” “brought about organization of the Tarrant County Construction Company,” which vowed to lay the track itself. Then “a waggish young lawyer” in Dallas (Cowart) wrote a “burlesque” of the Fort Worth meetings in a Dallas newspaper.

“At that time the joke was a severe one,” the Democrat recalled, “for the reason that it contained so much truthfulness.”

But, the Democrat wrote, “‘the place whar the pant[h]er laid down’ is now marked by . . . the hum of trade, the rattle and roar of wagons, the hurrying tread of busy men, the sound of ax, hammer and saw, the click of the trowel, the shrill scream of the many whistles of steam mills, planning mills, and of the locomotive.”

“During the period of dullness that existed when the [Cowart] fiction was invented, the Democrat was strong in its faith in the ‘City of Heights’ [another early nickname for Fort Worth], and retorted as best it could to the keen thrusts of its then successful rival [Dallas], and predicted the change that has taken place in the two cities . . . the ‘pant[h]er’ bids fair to invade the streets of the city that made sport of its then beautiful and unfortunate, but now happy and prosperous sister.”

To celebrate the arrival of the railroad, Paddock’s Democrat sported a new nameplate atop page 1. The nameplate does not reproduce well. At about the eight o’clock position on the circle is a train on a track approaching a town; at the six o’clock position is a reclining panther. Below are the words “where the panther laid down.”

Pantherville had gotten the last laugh.

Fast-forward two years. By 1878 the southern end of town around the passenger depot was booming. This image as seen from the depot shows a south-bound mule-drawn streetcar approaching on Main Street at today’s Lancaster Avenue.

Fast-forward two years. By 1878 the southern end of town around the passenger depot was booming. This image as seen from the depot shows a south-bound mule-drawn streetcar approaching on Main Street at today’s Lancaster Avenue.

This ad in the 1878 city directory shows T&P connections to St. Louis, Chicago, Memphis. From those and other cities Fort Worth residents could travel east to the very edge of America—to Boston, New York City. In Boston and New York City Cowtown residents could board a steamship and sail to Europe! All that on a trip—a trip made in a few days of relative comfort instead of in weeks of hardship in a wagon—that had begun in Fort Worth with a ticket bought in a one-story wooden building at the foot of Main Street.

This ad in the 1878 city directory shows T&P connections to St. Louis, Chicago, Memphis. From those and other cities Fort Worth residents could travel east to the very edge of America—to Boston, New York City. In Boston and New York City Cowtown residents could board a steamship and sail to Europe! All that on a trip—a trip made in a few days of relative comfort instead of in weeks of hardship in a wagon—that had begun in Fort Worth with a ticket bought in a one-story wooden building at the foot of Main Street.

Here is one early example of how the railroad connected Cowtown to the world: In 1878 five learned men from back east (Boston, Providence, St. Louis) traveled to Fort Worth by train to observe the lunar eclipse.

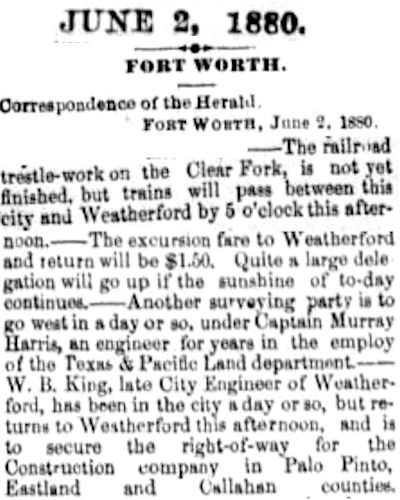

In 1880 Paddock’s tarantula map got its second leg as Texas & Pacific extended its track from Fort Worth west toward Benbrook, Weatherford, Abilene. By 1881 the T&P track met the Southern Pacific track being laid eastward at Sierra Blanca, Texas. Now people could walk into Fort Worth’s little wooden passenger depot, buy a ticket, and travel westward: to California. From California they could sail to the Orient! Spin a globe and place your finger anywhere on it. Beginning in 1876 for residents of Fort Worth a journey to that point began with a single step through the door of their little passenger depot.

In 1880 Paddock’s tarantula map got its second leg as Texas & Pacific extended its track from Fort Worth west toward Benbrook, Weatherford, Abilene. By 1881 the T&P track met the Southern Pacific track being laid eastward at Sierra Blanca, Texas. Now people could walk into Fort Worth’s little wooden passenger depot, buy a ticket, and travel westward: to California. From California they could sail to the Orient! Spin a globe and place your finger anywhere on it. Beginning in 1876 for residents of Fort Worth a journey to that point began with a single step through the door of their little passenger depot.

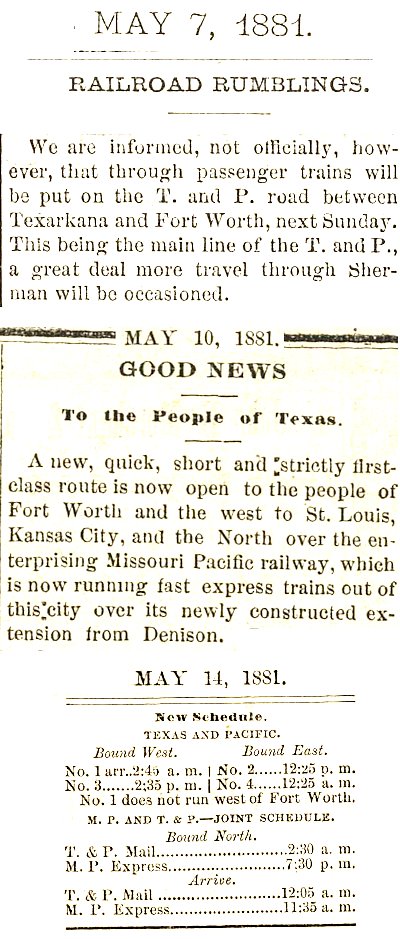

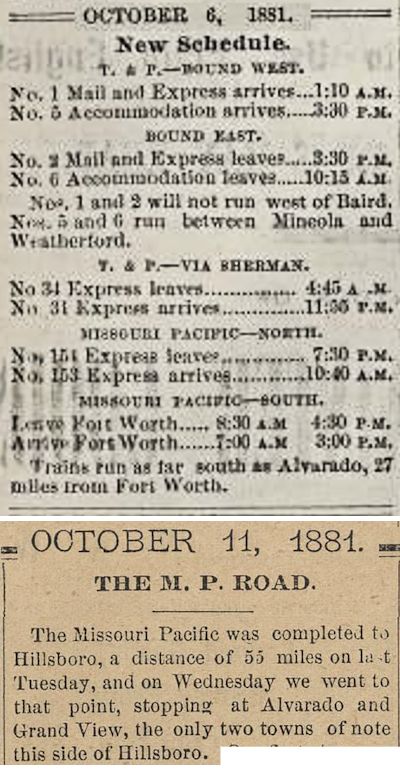

The year 1881 was indeed the Year of the Tarantula. In May the T&P opened a track north from Fort Worth to Sherman. The tarantula got a third leg. But this leg was a twofer: Not only the T&P but also the Missouri Pacific railroad began serving Fort Worth on that track. With two railroads Fort Worth became a hub: Passengers arriving on the T&P could transfer to the Missouri Pacific and vice versa.

The year 1881 was indeed the Year of the Tarantula. In May the T&P opened a track north from Fort Worth to Sherman. The tarantula got a third leg. But this leg was a twofer: Not only the T&P but also the Missouri Pacific railroad began serving Fort Worth on that track. With two railroads Fort Worth became a hub: Passengers arriving on the T&P could transfer to the Missouri Pacific and vice versa.

And in October the Missouri Pacific began serving Fort Worth from the south.

And in October the Missouri Pacific began serving Fort Worth from the south.

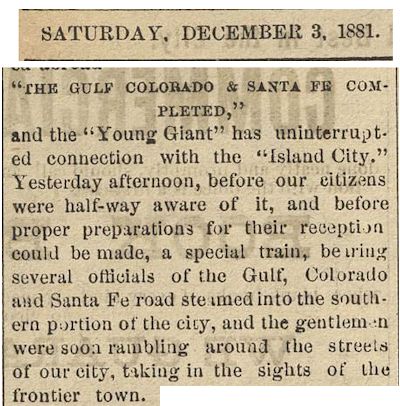

And the Santa Fe began service from the south in December 1881. “Young Giant” was one of the Democrat’s nicknames for Fort Worth.

And the Santa Fe began service from the south in December 1881. “Young Giant” was one of the Democrat’s nicknames for Fort Worth.

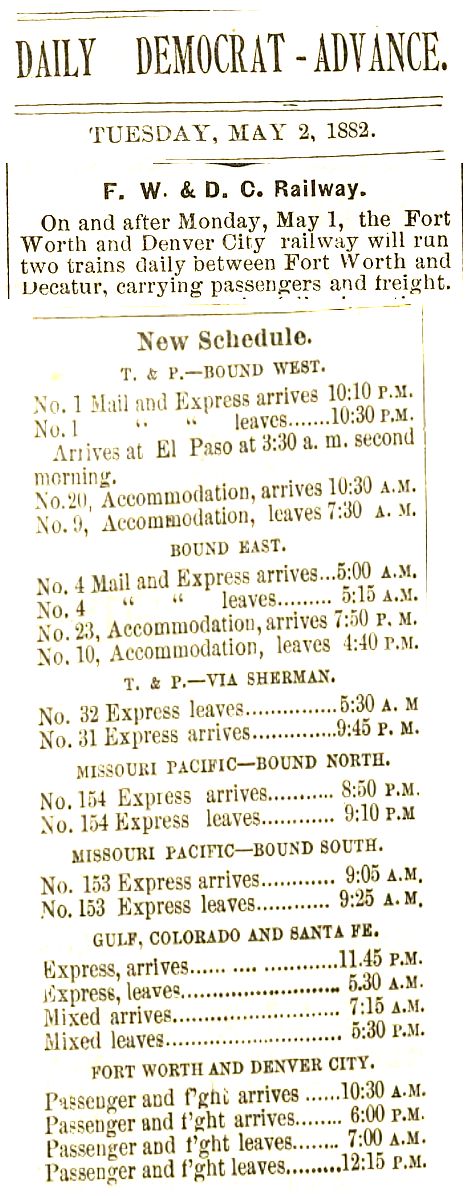

In May 1882 the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began service, if only to Decatur, not Denver.

In May 1882 the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began service, if only to Decatur, not Denver.

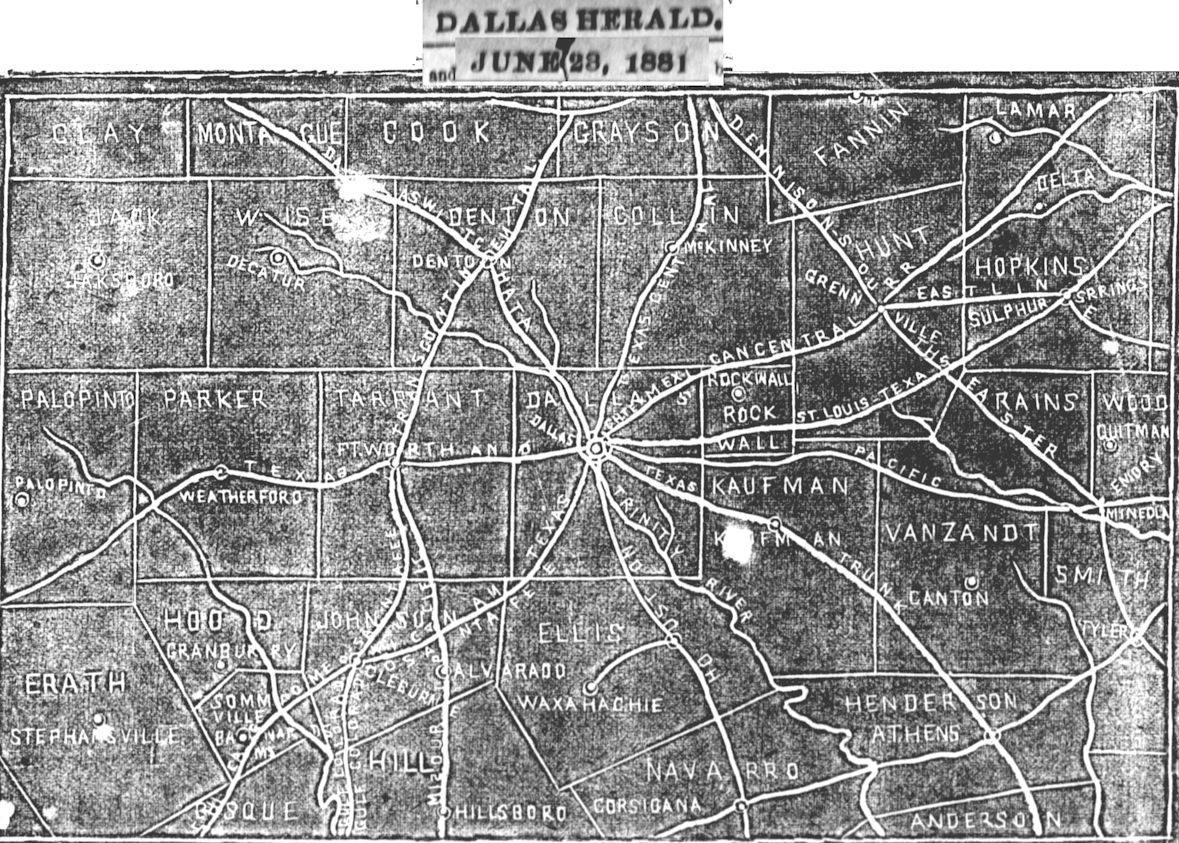

In June 1881 the Dallas Herald published its own version of the tarantula map, showing these legs for Fort Worth: Texas & Pacific, T&P Transcontinental, Santa Fe, and Missouri Pacific.

In June 1881 the Dallas Herald published its own version of the tarantula map, showing these legs for Fort Worth: Texas & Pacific, T&P Transcontinental, Santa Fe, and Missouri Pacific.

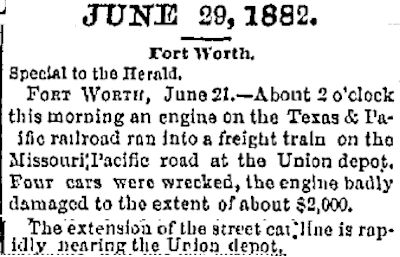

Addition of these railroads created the need for a new passenger depot. In 1881 Texas & Pacific began construction of its Union Depot. The depot had not been open long in 1882 before two trains collided where the east-west and north-south tracks crossed.

Addition of these railroads created the need for a new passenger depot. In 1881 Texas & Pacific began construction of its Union Depot. The depot had not been open long in 1882 before two trains collided where the east-west and north-south tracks crossed.

Note that the streetcar line was being extended to the new depot, possibly from the 1876 passenger depot.

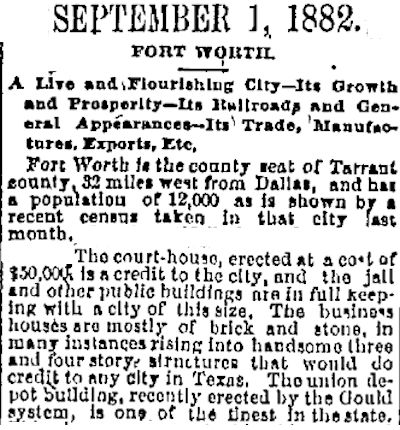

In September 1882 the Dallas Herald, in a roundup of the Texas economy, noted the progress in Fort Worth, including the “recently erected” Union Depot.

In September 1882 the Dallas Herald, in a roundup of the Texas economy, noted the progress in Fort Worth, including the “recently erected” Union Depot.

In October 1882 the Dallas Herald reported that a hotel next to the Union Depot was being completed.

In October 1882 the Dallas Herald reported that a hotel next to the Union Depot was being completed.

The 1882 Union Depot was an L-shaped two-story wooden building with a tower at its outer right angle.

The 1882 Union Depot was an L-shaped two-story wooden building with a tower at its outer right angle.

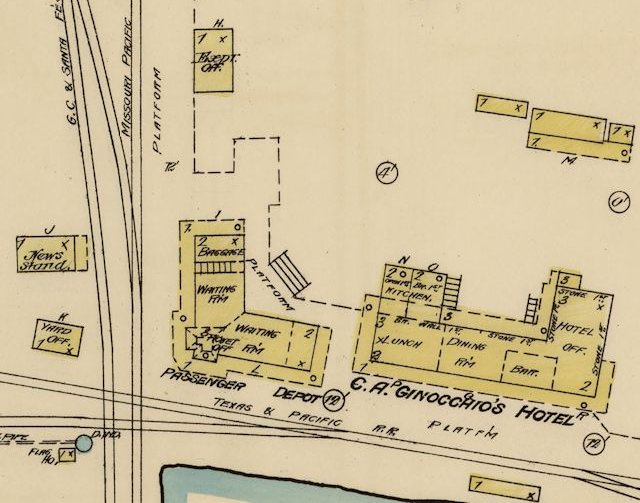

Next to the depot stood Ginocchio’s Hotel. John Laneri was proprietor of the hotel restaurant. On the 1886 Wellge bird’s-eye-view map detail, the new depot is under the label “1882.” Ginocchio’s Hotel is to the left, labeled “81.” At the label “28” is a streetcar leaving the depot/hotel area. The little building under the label “1876” probably is the original passenger depot at the foot of Main Street. The three-story building below the little building is the 1886 Joseph H. Brown building. We’ll come back to that. (Top illustration from Pete Charlton.)

The new Union Depot was located east of the 1876 passenger depot (in the center of today’s I-20/I-35 mixmaster at Tower 55).

By 1882 the passenger depot of 1876 had served as Fort Worth’s gateway to the globe for only six years. The little depot that could was demoted, converted into a freight depot. And with its reassignment as a freight depot, the building began to lose its original identity to future generations.

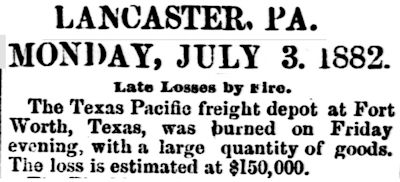

But why, you ask, would the T&P convert the old passenger depot into a freight depot? After all, didn’t the T&P already have a freight depot? Correct. Until June 30, 1882, just after the Union Depot opened. Several newspapers, including the Intelligencer of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, reported that the Texas & Pacific freight depot in Fort Worth and its contents had been destroyed by fire on June 30.

But why, you ask, would the T&P convert the old passenger depot into a freight depot? After all, didn’t the T&P already have a freight depot? Correct. Until June 30, 1882, just after the Union Depot opened. Several newspapers, including the Intelligencer of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, reported that the Texas & Pacific freight depot in Fort Worth and its contents had been destroyed by fire on June 30.

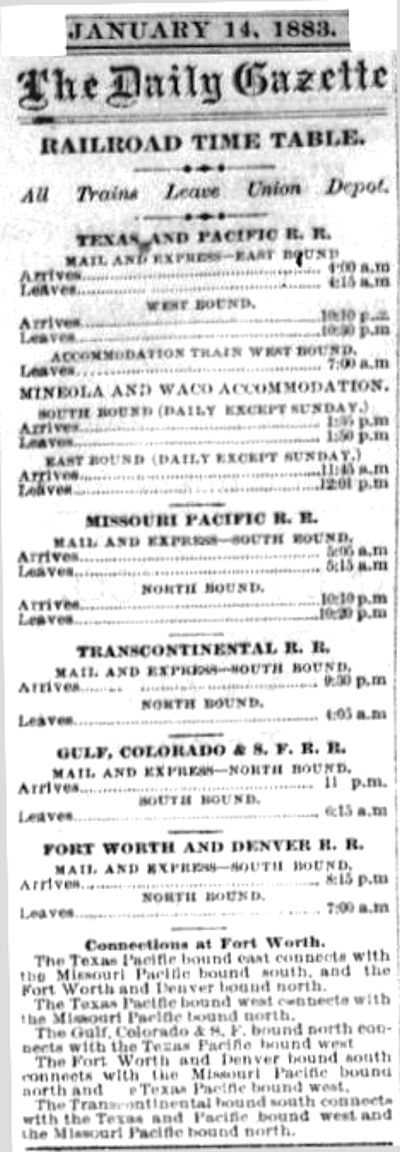

By 1883 the Union Depot served these passenger trains. The time table published each day in the Gazette listed the arrival and departure times and the connections between railroads.

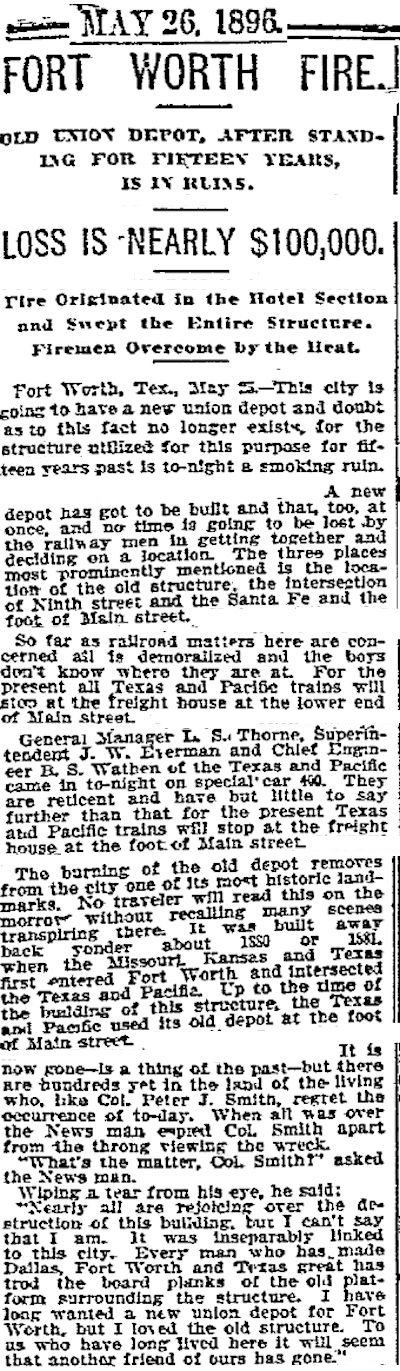

Fast-forward to 1896. The 1876 passenger depot-turned-freight depot was promoted. Fittingly, by another fire. (Remember: The nineteenth century was an era of wooden buildings that were heated and illuminated by fire.) On May 25, 1896 the 1882 Union Depot and Ginocchio’s Hotel burned. Among the three locations considered for the replacement depot was “the foot of Main Street” at Lancaster—where the 1876 passenger depot was located.

Fast-forward to 1896. The 1876 passenger depot-turned-freight depot was promoted. Fittingly, by another fire. (Remember: The nineteenth century was an era of wooden buildings that were heated and illuminated by fire.) On May 25, 1896 the 1882 Union Depot and Ginocchio’s Hotel burned. Among the three locations considered for the replacement depot was “the foot of Main Street” at Lancaster—where the 1876 passenger depot was located.

After the fire John Peter Smith paid tribute to the 1882 Union Depot, recalling that “every man who has made Dallas, Fort Worth and Texas great” had passed through the building.

Note the mention of T&P Superintendent John Wesley Everman, namesake of the Tarrant County city.

When the “foot of Main Street” site was indeed selected for the new passenger depot, the 1876 passenger depot—by 1896 serving as “the freight house at the foot of Main Street”—apparently was moved down the track away from the construction area and again served as Fort Worth’s passenger depot during construction of the new passenger depot. The 1876 passenger depot was small and rested on wooden blocks, secured only by its own weight.

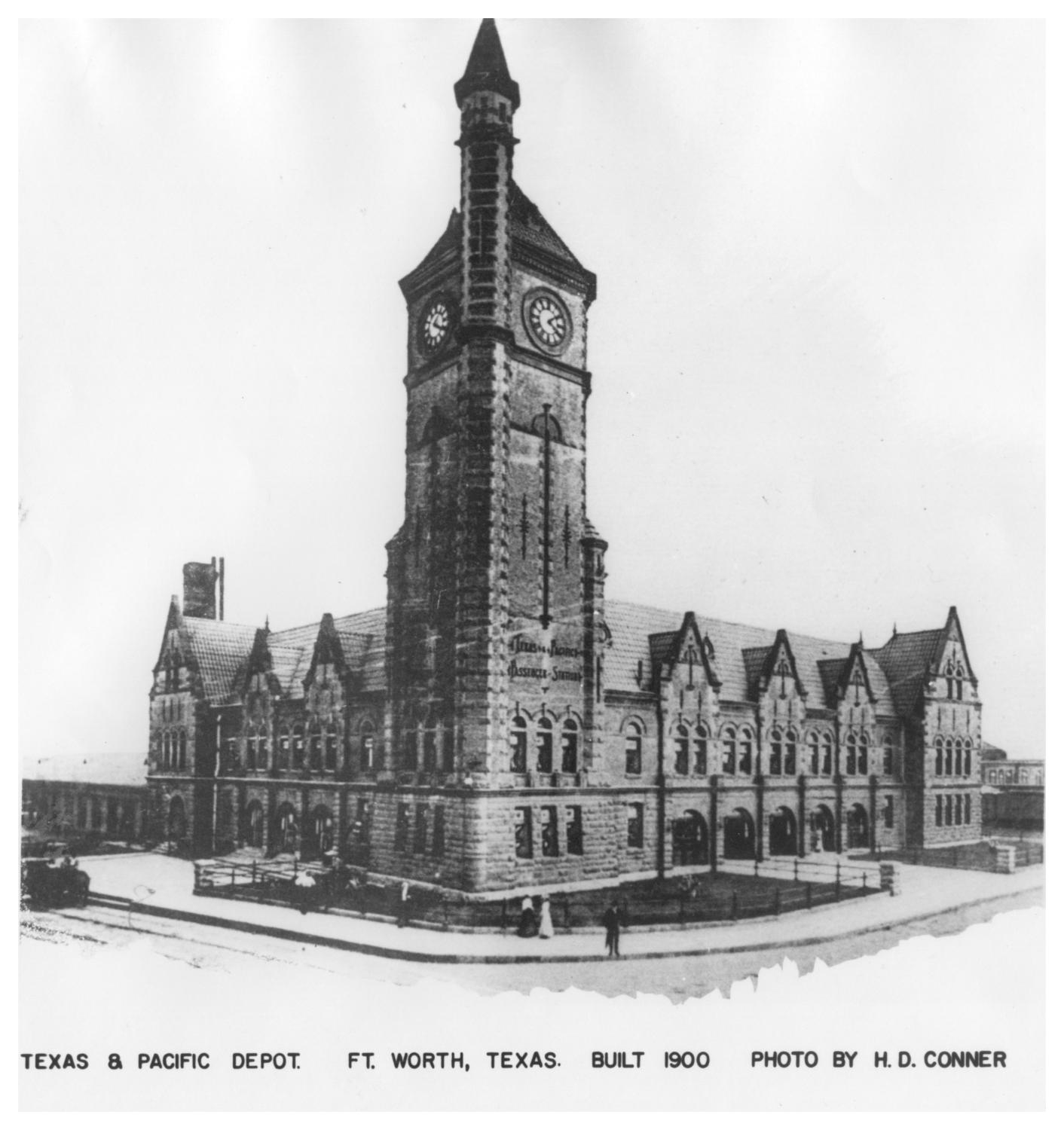

After the grand new passenger depot opened in 1899, the 1876 passenger depot was again demoted to freight depot.

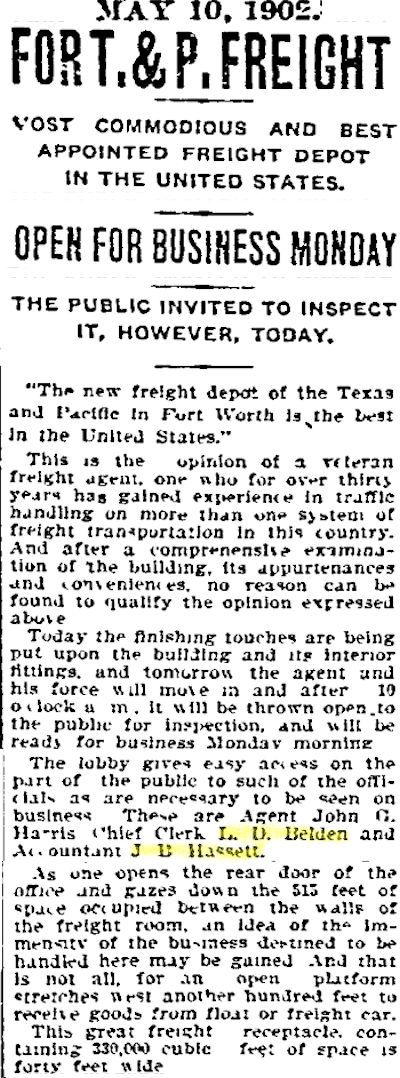

In 1902 Texas & Pacific built a huge (more than five hundred feet long) freight depot west of the 1899 passenger depot. (President Theodore Roosevelt would address a crowd from the 1902 freight depot during his visit in 1905. He also would address a crowd from his train car behind the passenger depot.)

In 1902 Texas & Pacific built a huge (more than five hundred feet long) freight depot west of the 1899 passenger depot. (President Theodore Roosevelt would address a crowd from the 1902 freight depot during his visit in 1905. He also would address a crowd from his train car behind the passenger depot.)

Note the names of L. D. Belden and J. B. Hassett in the clip. We’ll come back to them.

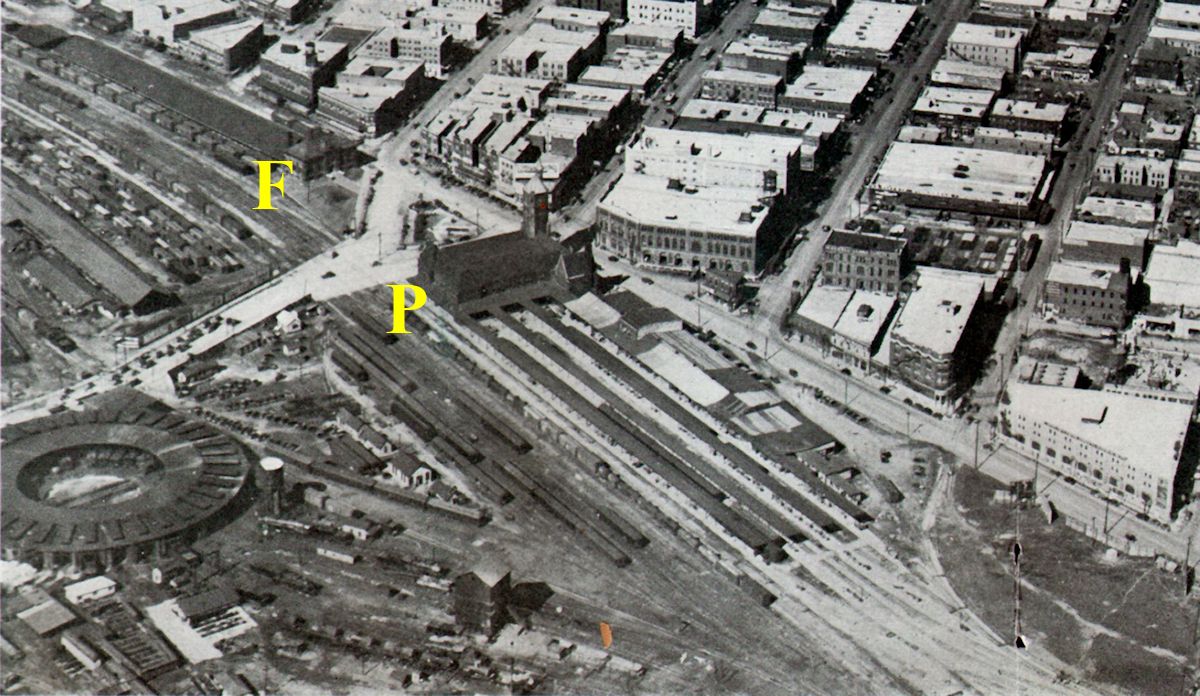

The 1928 aerial photo shows the 1908 freight depot (F; it replaced the 1902 freight depot, which burned in 1908) and 1899 passenger depot (P). In the Main Street traffic triangle between them is the Al Hayne memorial. Note that in 1928 Main Street was still a grade crossing at the T&P tracks. That would change in 1931. The roundhouse and turntable are in the lower left.

The 1928 aerial photo shows the 1908 freight depot (F; it replaced the 1902 freight depot, which burned in 1908) and 1899 passenger depot (P). In the Main Street traffic triangle between them is the Al Hayne memorial. Note that in 1928 Main Street was still a grade crossing at the T&P tracks. That would change in 1931. The roundhouse and turntable are in the lower left.

After the 1902 freight depot opened, the little depot that could was moved again, “out of commission and out of the way” elsewhere on the T&P reservation, the Telegram wrote in 1903.

After the 1902 freight depot opened, the little depot that could was moved again, “out of commission and out of the way” elsewhere on the T&P reservation, the Telegram wrote in 1903.

But the 1876 passenger depot endured one more relocation and one more demotion: In 1903, the Telegram wrote, rollers were placed under the building, and a team of horses pulled it to the southwest corner of the T&P reservation on Vickery Boulevard near the Jennings Avenue viaduct, where the building served as a lowly section house until the wrecking crew arrived in 1931.

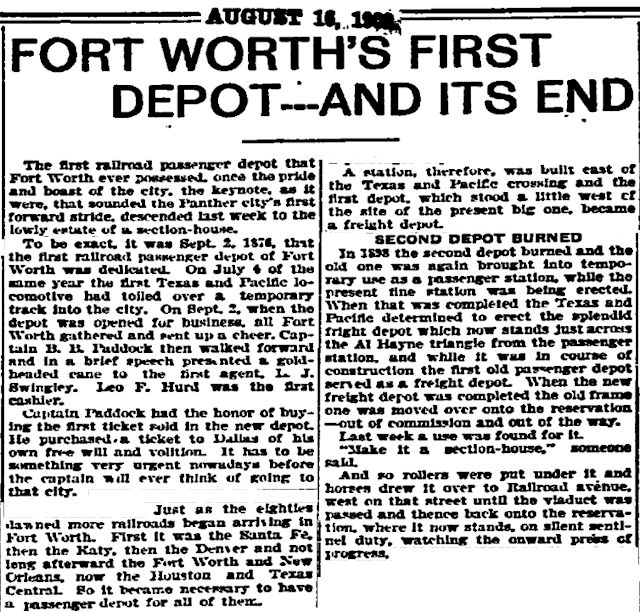

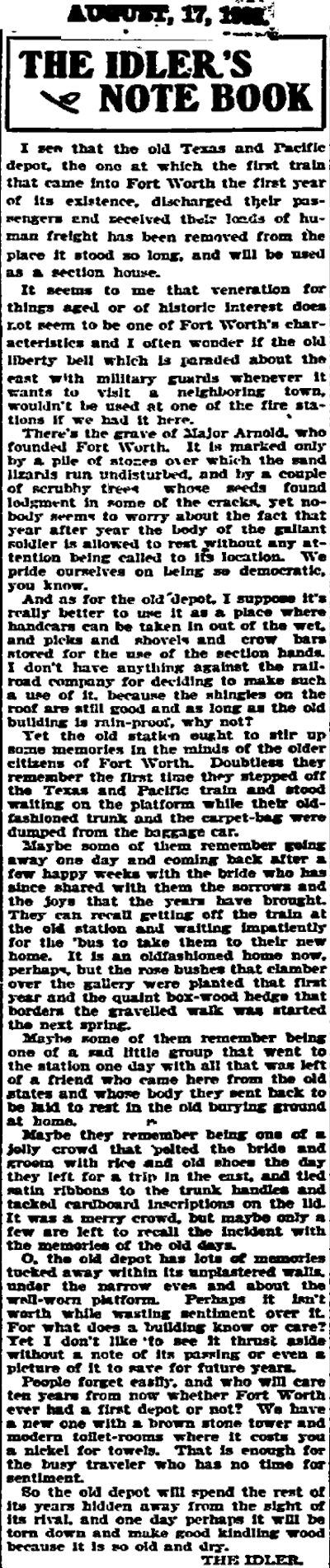

With removal and reassignment of Fort Worth’s first passenger depot to a corner of the T&P reservation, an editorial in the Telegram observed that “veneration for things aged or of historic interest does not seem to be one of Fort Worth’s characteristics.” “So the old depot will spend the rest of its years hidden away from the sight of its rival, and perhaps one day it will be torn down and make good kindling wood because it is so old and dry.”

With removal and reassignment of Fort Worth’s first passenger depot to a corner of the T&P reservation, an editorial in the Telegram observed that “veneration for things aged or of historic interest does not seem to be one of Fort Worth’s characteristics.” “So the old depot will spend the rest of its years hidden away from the sight of its rival, and perhaps one day it will be torn down and make good kindling wood because it is so old and dry.”

Fast-forward to 1904. Another year, another fire. In 1904 the 1899 passenger depot was damaged by fire, but this time the 1876 passenger depot was not recalled to active duty. The 1899 depot continued in operation as it was repaired. The damaged roof was covered temporarily by rubberized sheets. Passengers waited for trains on the platforms instead of inside the depot. (Charles Swartz photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Fast-forward to 1904. Another year, another fire. In 1904 the 1899 passenger depot was damaged by fire, but this time the 1876 passenger depot was not recalled to active duty. The 1899 depot continued in operation as it was repaired. The damaged roof was covered temporarily by rubberized sheets. Passengers waited for trains on the platforms instead of inside the depot. (Charles Swartz photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

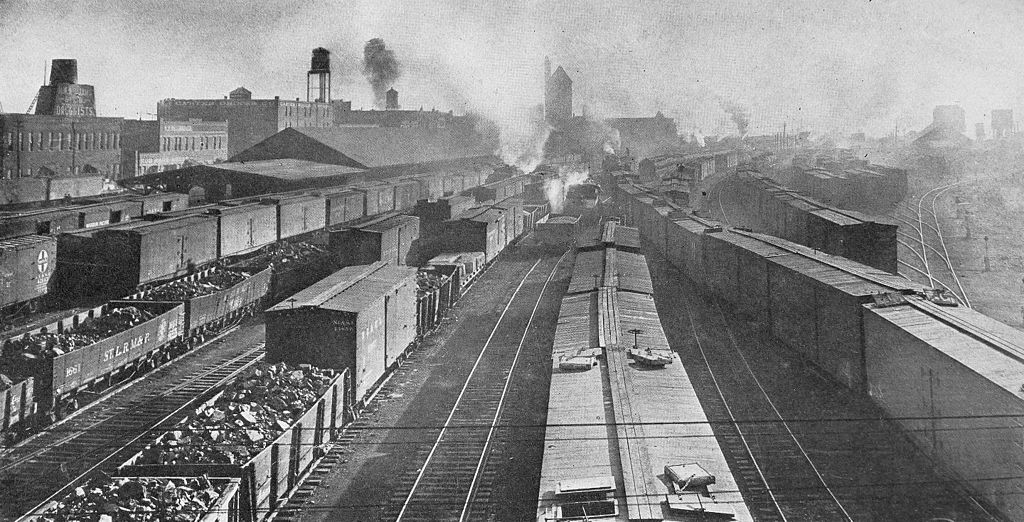

Looking east over the T&P railyard in 1916. The clock tower of the 1899 passenger depot is in top center. The building with a long gabled roof on the left is the 1902 freight depot. The 1876 passenger depot-turned-section house is out of view to the right. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Looking east over the T&P railyard in 1916. The clock tower of the 1899 passenger depot is in top center. The building with a long gabled roof on the left is the 1902 freight depot. The 1876 passenger depot-turned-section house is out of view to the right. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

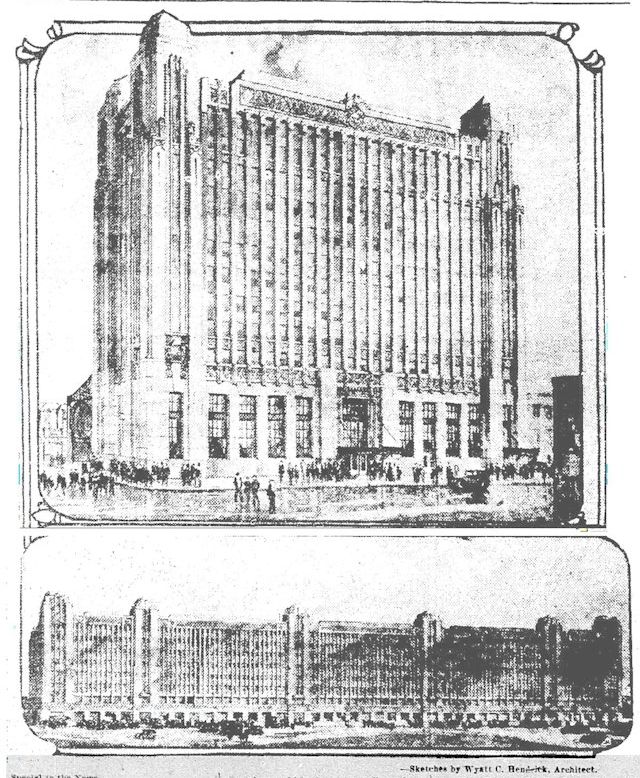

In 1931 the little depot that could was demolished five months before the Texas & Pacific opened its massive new freight depot (six hundred feet long) and ten months before the T&P opened its new (fourth) passenger depot.

In 1931 the little depot that could was demolished five months before the Texas & Pacific opened its massive new freight depot (six hundred feet long) and ten months before the T&P opened its new (fourth) passenger depot.

This photo taken in 1930 shows the 1931 depot under construction. To the right is the 1899 depot. Between can be seen the front of the 1908 freight depot, the Joseph H. Brown building (1886), and the Monnig’s warehouse (1925). (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

When the new depot opened, the 1899 depot was demolished.

When the new depot opened, the 1899 depot was demolished.

Here are the locations of Texas & Pacific’s four passenger depots and the last location (1903) of the first depot.

Here are the locations of Texas & Pacific’s four passenger depots and the last location (1903) of the first depot.

At this point, after reading so much about Fort Worth’s first passenger depot and seeing images of the second, third, and fourth depots, you might ask, “Do any images of the 1876 depot exist?”

I had found only one illustration, and it is of dismal quality. So I kept searching. Because newspaper accounts tell us that from 1876 until well into the 1890s the 1876 depot was located where the track crosses Main Street, and because the Star-Telegram in 1931 described the 1876 building as “a modest, two-room, frame depot, located on almost the exact site of the new passenger terminal,” we have a location and a relative size to keep in mind when we look at photos and maps.

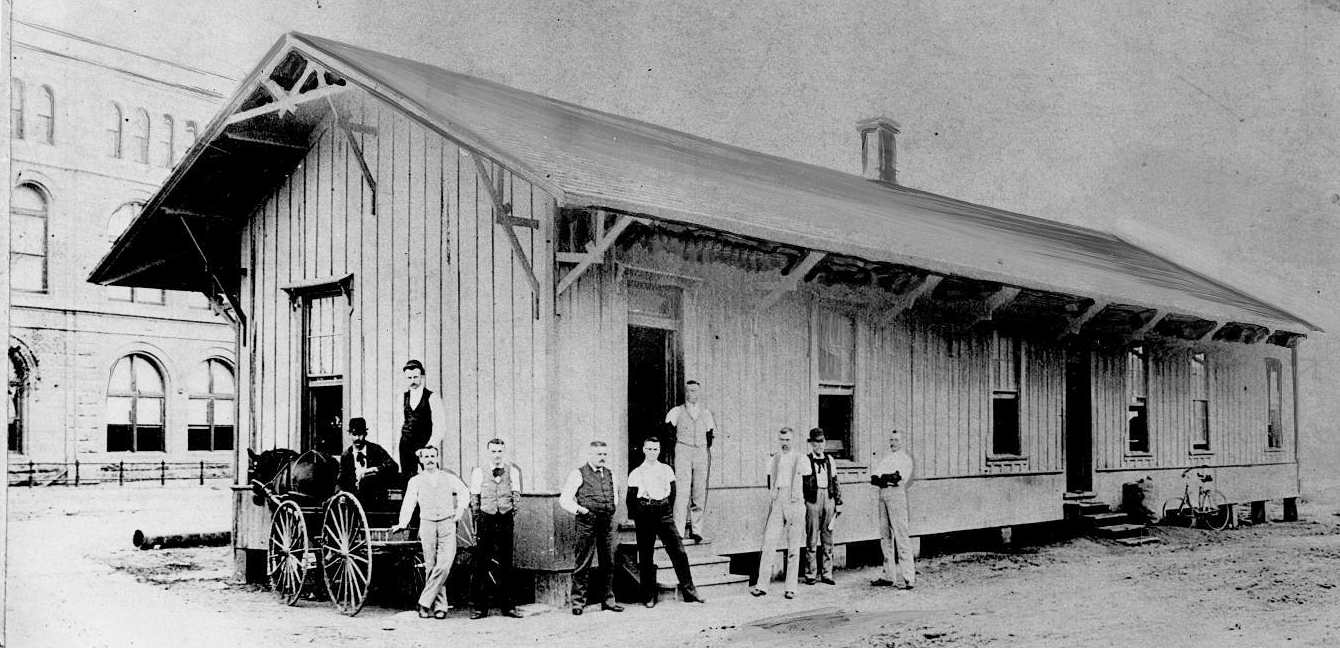

Now to solve—maybe—a history mystery. I came across this photo at University of Texas at Arlington Library. The caption describes the photo as “Texas and Pacific freight station, Fort Worth, Texas” but gives no date for the photo. But the caption identifies nine of the ten men. Of those nine, I found six listed as Fort Worth railroad men in censuses and city directories of the 1890s. The building is essentially a shotgun house with board-and-batten siding, resting on wooden blocks. Note the windows of the stone building in the background. We’ll come back to those.

Now to solve—maybe—a history mystery. I came across this photo at University of Texas at Arlington Library. The caption describes the photo as “Texas and Pacific freight station, Fort Worth, Texas” but gives no date for the photo. But the caption identifies nine of the ten men. Of those nine, I found six listed as Fort Worth railroad men in censuses and city directories of the 1890s. The building is essentially a shotgun house with board-and-batten siding, resting on wooden blocks. Note the windows of the stone building in the background. We’ll come back to those.

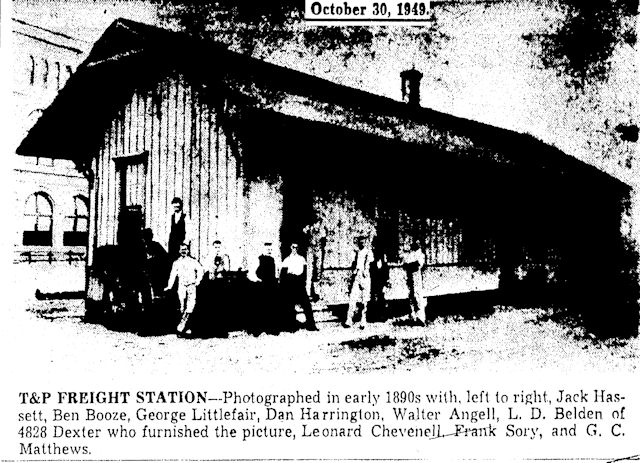

Sure enough, I then found the photo in the edition of the Star-Telegram celebrating Fort Worth’s centennial in 1949. The caption says the photo is from the early 1890s. Among the names note those of L. D. Belden and J. B. Hassett, who later worked at the 1902 T&P freight depot. Belden supplied the photo to the newspaper in 1949.

Sure enough, I then found the photo in the edition of the Star-Telegram celebrating Fort Worth’s centennial in 1949. The caption says the photo is from the early 1890s. Among the names note those of L. D. Belden and J. B. Hassett, who later worked at the 1902 T&P freight depot. Belden supplied the photo to the newspaper in 1949.

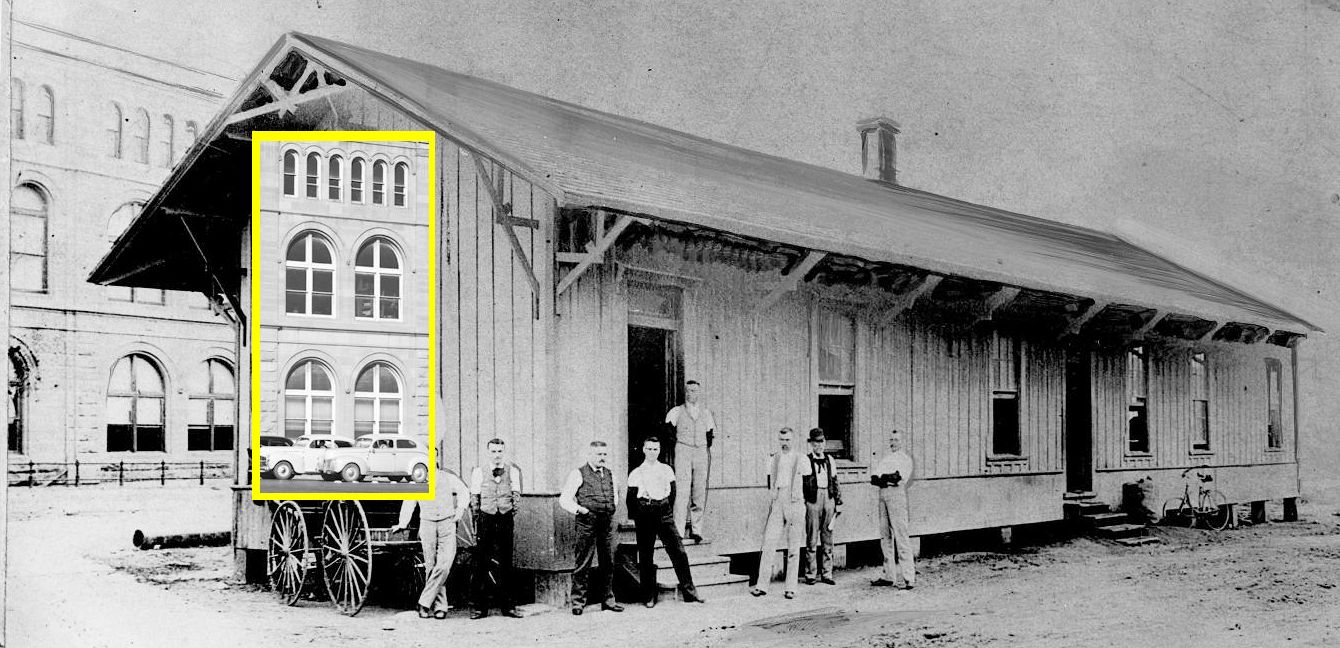

So. We have a time period for the photo: early 1890s. But we still have no location. Or do we? Look again at the windows of the stone building in the background.

Bingo. That’s the building that Joseph H. Brown built in 1886 at the intersection of Main and Lancaster across from the 1876 passenger depot. That places the “freight depot” in the early 1890s photo at the foot of Main Street, where the 1876 passenger depot was serving as the freight depot after its demotion. Lancaster Avenue (unpaved) is between the depot and the Brown building; the men are facing the T&P tracks, which are out of view in this photo.

Bingo. That’s the building that Joseph H. Brown built in 1886 at the intersection of Main and Lancaster across from the 1876 passenger depot. That places the “freight depot” in the early 1890s photo at the foot of Main Street, where the 1876 passenger depot was serving as the freight depot after its demotion. Lancaster Avenue (unpaved) is between the depot and the Brown building; the men are facing the T&P tracks, which are out of view in this photo.

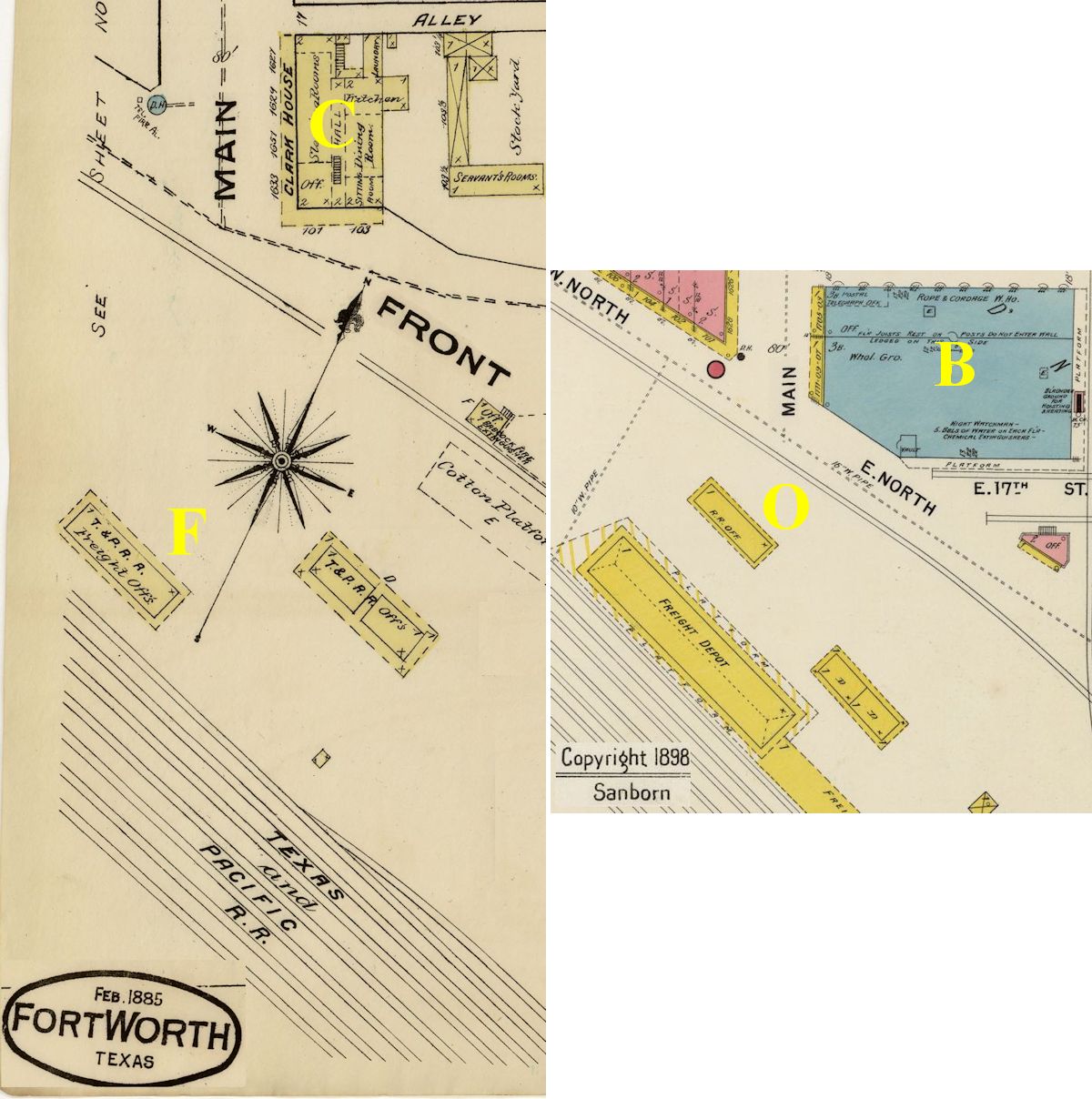

The shape and location of the depot building in the photo match the shape and location of a T&P building shown in Sanborn maps from 1885 to 1898. The building is sometimes labeled as freight, sometimes as offices. In 1885 the Clark House hotel was across Lancaster; it was replaced by the Joseph H. Brown building in 1886. Lancaster Avenue before 1931 was known as “Front Street” and “North Street.”

The shape and location of the depot building in the photo match the shape and location of a T&P building shown in Sanborn maps from 1885 to 1898. The building is sometimes labeled as freight, sometimes as offices. In 1885 the Clark House hotel was across Lancaster; it was replaced by the Joseph H. Brown building in 1886. Lancaster Avenue before 1931 was known as “Front Street” and “North Street.”

The 1876 passenger depot had to be moved—probably in late 1898 or early 1899—to make way for the new depot.

Apparently with the passage of time the history of the 1876 building got lost between generations. Perhaps Generation 1 knew that the old building—now a freight depot or a section house—had been the first passenger depot but failed to pass that history along to Generation 2. Thus, Generation 2 knew the building only as what it is, not as what it was.

By 1931, when the “section house” was torn down, Texas & Pacific oldtimers knew that it had been used as the passenger depot from 1896 to 1899 but not that it also was the original passenger depot of 1876.

Granted, the 1876 passenger depot lacked the wild West associations (Jim Courtright’s arrest and escape of 1884, the railroad strike of 1886) of the 1882 depot, the presidential associations of the 1899 depot, the architectural grandeur of the 1931 depot. But the little depot that could—could be a passenger depot, could be a freight depot, could be a section house—was something that the three later depots could not be: Fort Worth’s first iron gateway to the globe.

My internet search regarding the location of the Fort Worth Ginocchio Hotel lead me to this most informative article. As current owner’s of Charles Ginocchio’s home built in 1886 in Marshall, TX, my wife and I take great interest in his history and ties to the T&P Railroad. Our home stands next to the only remaining Ginocchio hotel still standing, which was constructed in 1896. A fine dining establishment is currently operating on its lower level and is a beautiful site to visit for those interested in such history. From what we know, Charles Ginocchio died from a heart attack in 1898 in his Fort Worth hotel. Since the original burned alongside the Union Depot in 1896, would that mean that he rebuilt, and if so, where? Could it still be standing?

David, you live in a historic town, especially for Texas railroad history. In 1897 Ginocchio told a reporter he was confident that he would rebuild soon on the site of the Windsor Hotel, which he owned at the corner of Front Street (Lancaster Avenue) and Jones Street.

But he died in 1898 and apparently never rebuilt in Fort Worth. There is no Ginocchio in city directories after 1896.

Our company purchased an older building said to be built in 1950 but I beleive it is way older. The purchase is to renovate it into our “new” general offices. The address of the building is 722 Missouri but I have a suspicion that the main address use to be on E. Leuda Street around the 700 block. Rumor has it that parts of this building use to be a furniture store and an ice factory. I have been unsuccessful to locate anything other than the most recent occupier of the building being Fred Clark Felt Company before the building was sold in 2018. Any suggestions on where I can find more about this structure? Thank you

Larry, I have e-mailed you all the information I have. Good luck.

Excellent sleuthing! My take is the photo shows the original passenger depot in its role as a freight office. It’s too small at that point to be a freight depot. I don’t see large doors for cargo to be loaded in and out of the building. No loading dock either. In an earlier sketch, the building looks longer and had a loading dock around it and most assuredly served as a freight depot at that time.

Now if only we could find a trackside view of the second T&P passenger depot!

By the way, the Katy would have been called the Missouri Pacific in the 1880s.

Thanks, Dennis. I spent days researching to come to the conclusion that the building was the first passenger depot and only after I was done did I see online the photo in an old magazine. The photo was labeled “Fort Worth’s first passenger depot”!

I have made the Katy correction.

Thank you for this fascinating window into Fort Worth and railroad history. It is sad that so many historic structures were not appreciated and preserved for future generations.

Thank you, Kathy. That little building could have been moved to safety as easily as it was demolished if only the T&P folks of 1931 had known what the T&P folks of 1903 knew.

Thank you for all the research you do to write these incredible articles for all to enjoy. This is one of your best!

Thank you, Leo. Despite the importance of the railroads to Fort Worth, facts about their early years here are spotty. I hope this fills in a few gaps.